A New Method for Screening Thalassemia Patients Using Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Analysis of Blood Samples Using IR Microspectroscopy

2.2. Spectral Preprocessing and Multivariate Data Analysis

2.3. Construction of a Spectral Database for Thalassemia Classification

| Parameter | Criterion (Screening/Diagnostic Cut-Off) | References |

|---|---|---|

| RBC count (×106/µL) | >5.0 indicates microcytic erythrocytosis (suggestive of thalassemia trait) | [48,49] |

| Hemoglobin (Hb, g/dL) | <12.0 indicates anemia; <10.0 suggests moderate to severe anemia | [48,50] |

| Hematocrit (Hct, %) | <36% considered anemic threshold | [48,49] |

| Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV, fL) | <80 fL indicates microcytosis | [48,51,52] |

| Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin (MCH, pg) | <27 pg indicates hypochromia | [48,50] |

| Red Cell Distribution Width (RDW, %) | >14% indicates anisocytosis; may support thalassemia or IDA | [49,51] |

| HbA2 (%) | >3.5% diagnostic for β-thalassemia trait | [50,51] |

| HbE (%) | 25–30% diagnostic for HbE trait | [50,51] |

| HbF (%) | >1% suggests β-thalassemia intermedia or major | [49,51] |

3. Results

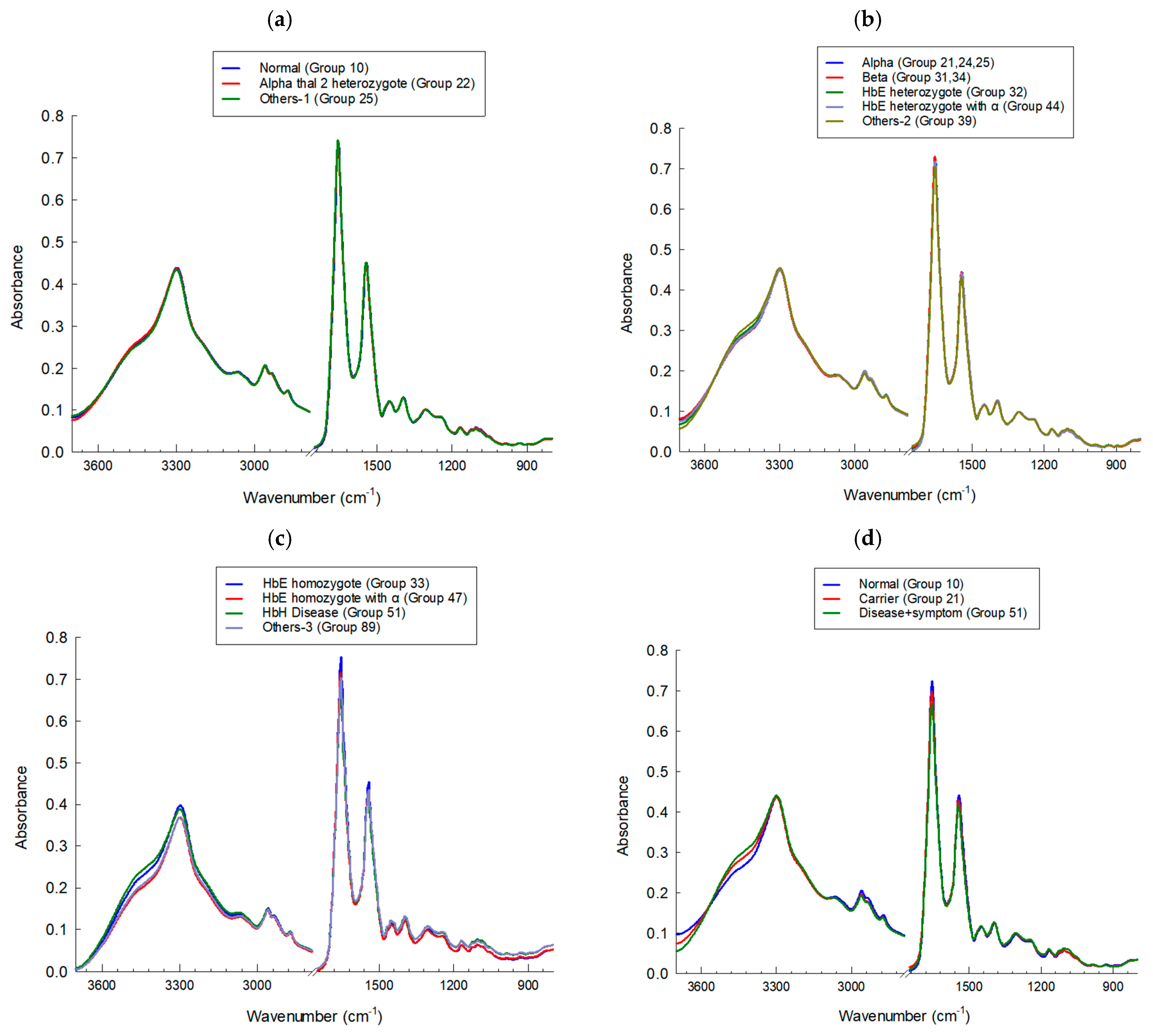

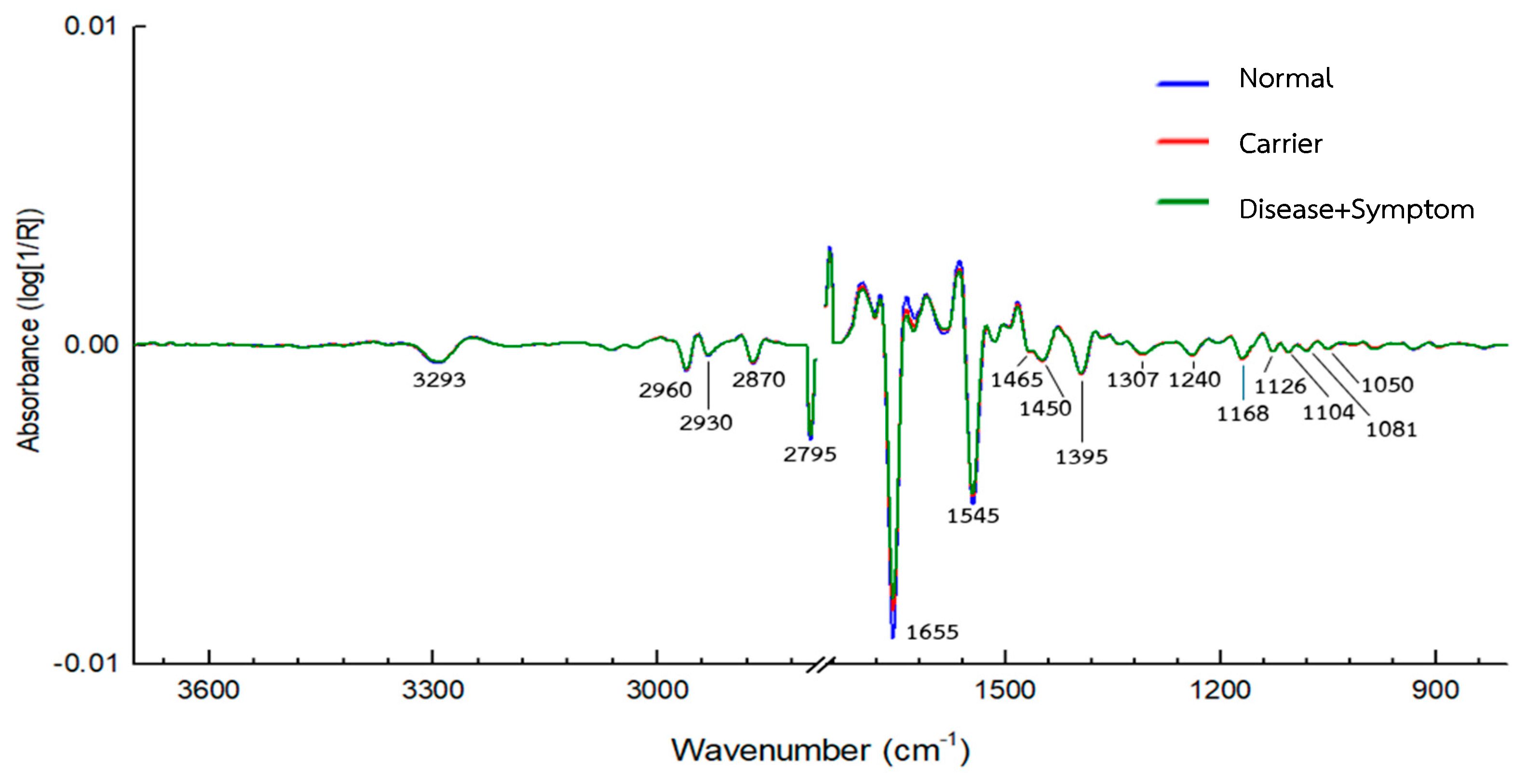

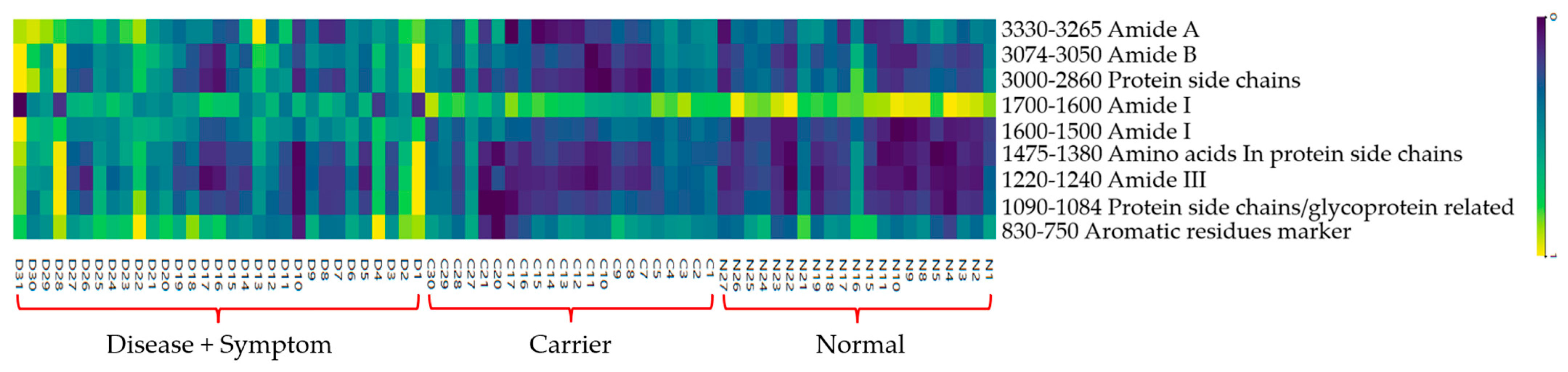

3.1. IR Microspectroscopy and Functional Group Analysis

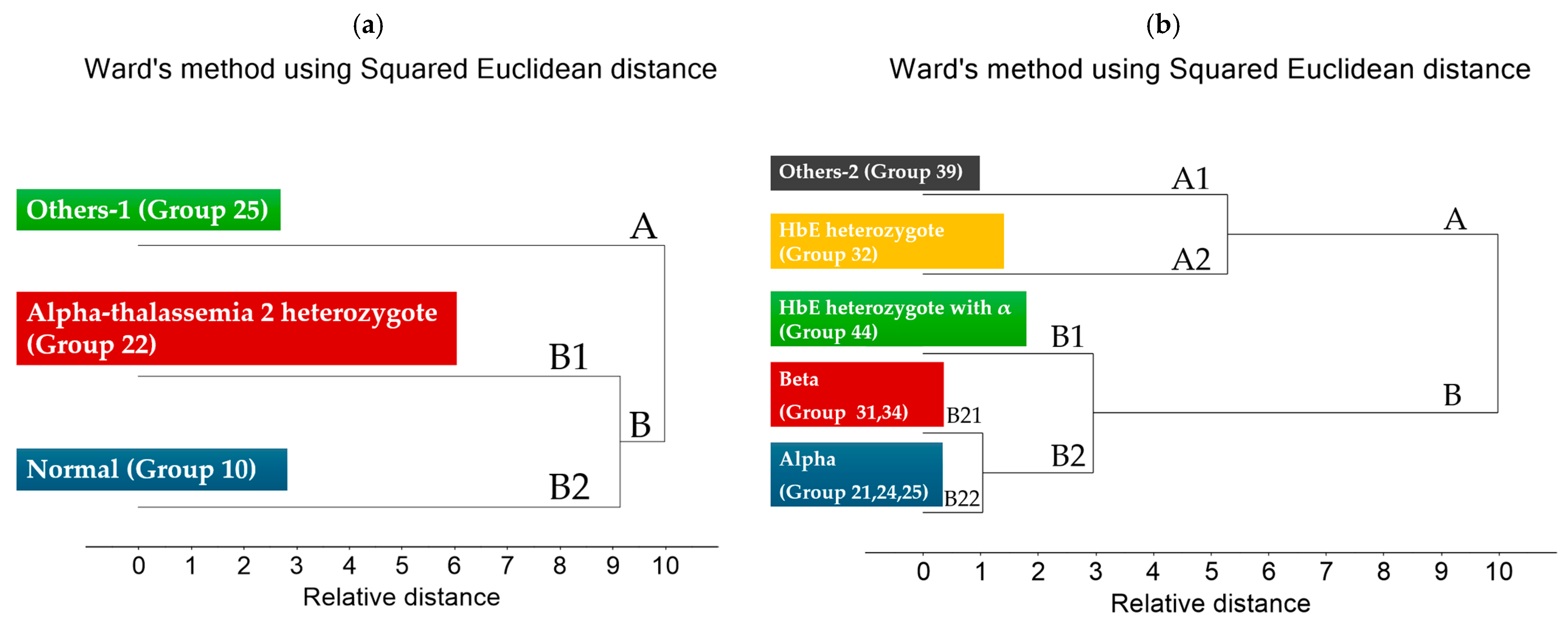

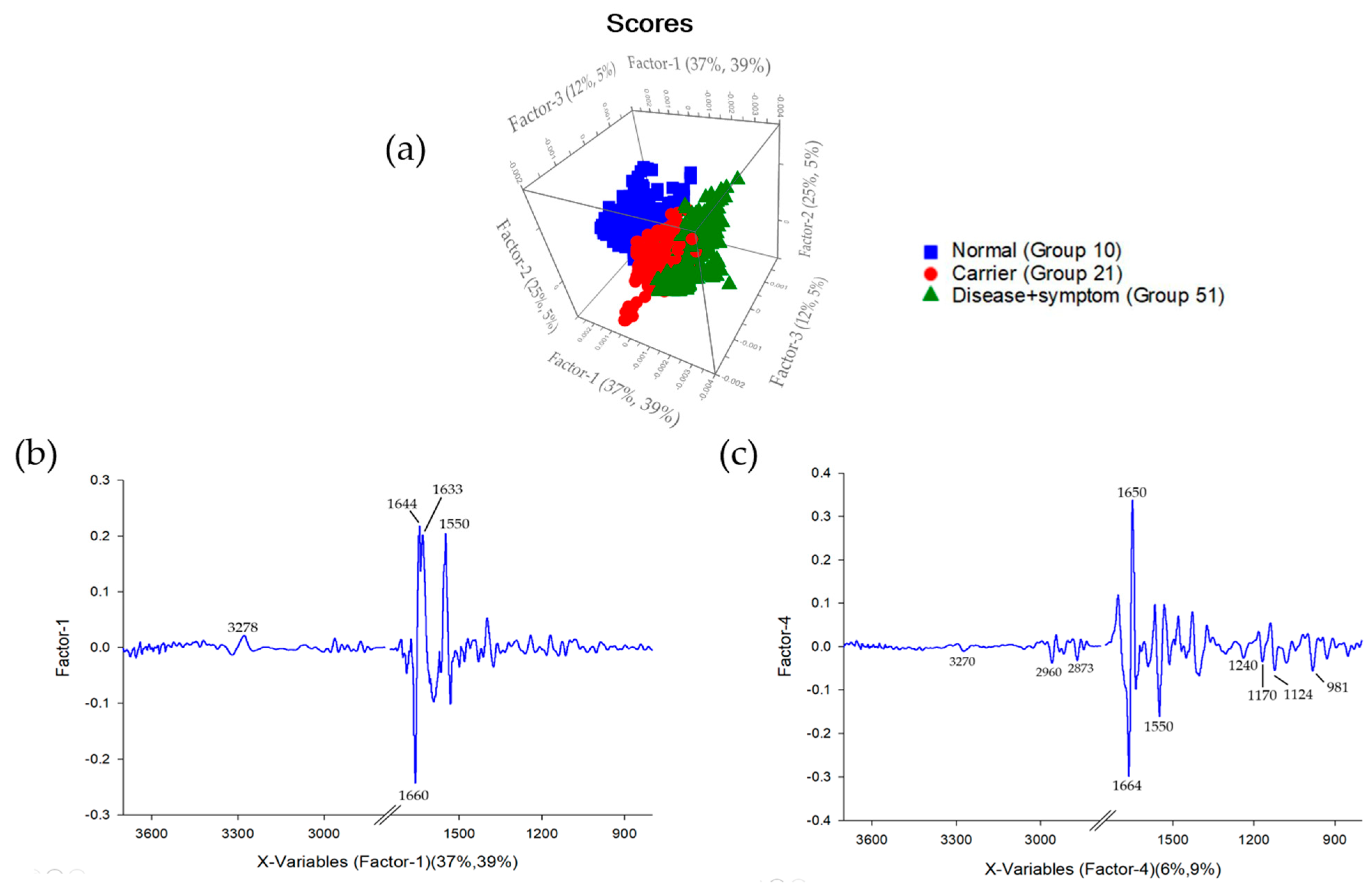

3.2. Cluster Analysis of FTIR Spectra of Hb Lysate

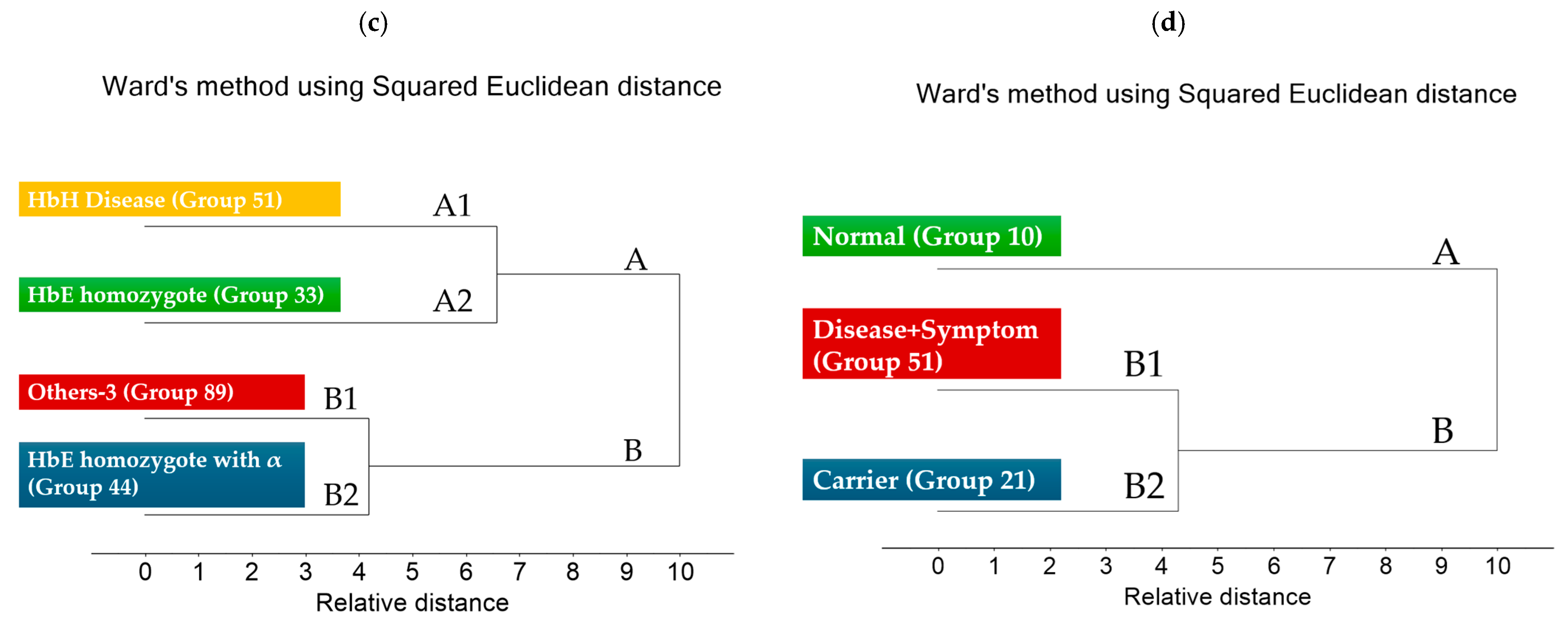

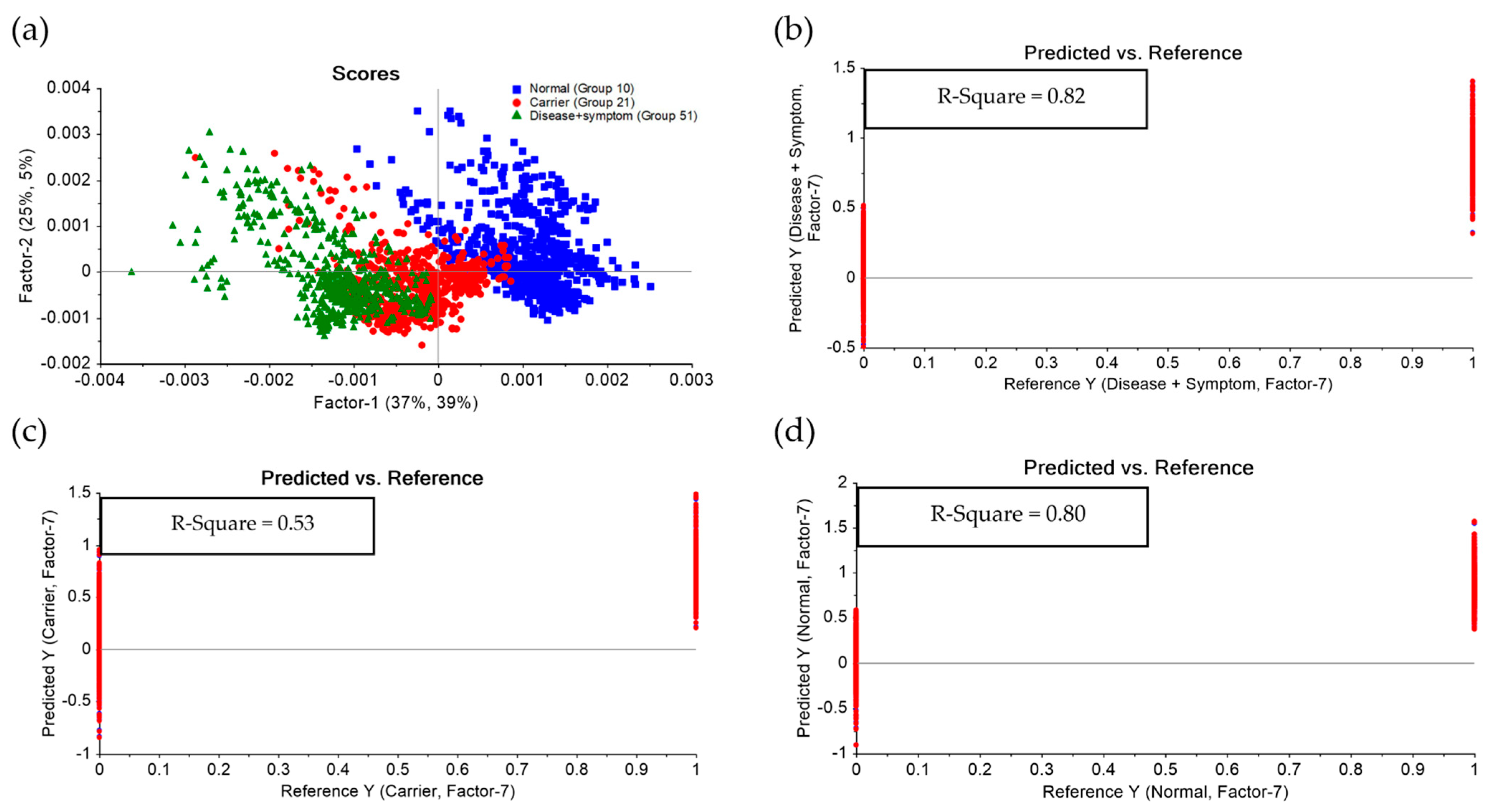

3.3. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) of FTIR Spectra of Hb Lysate

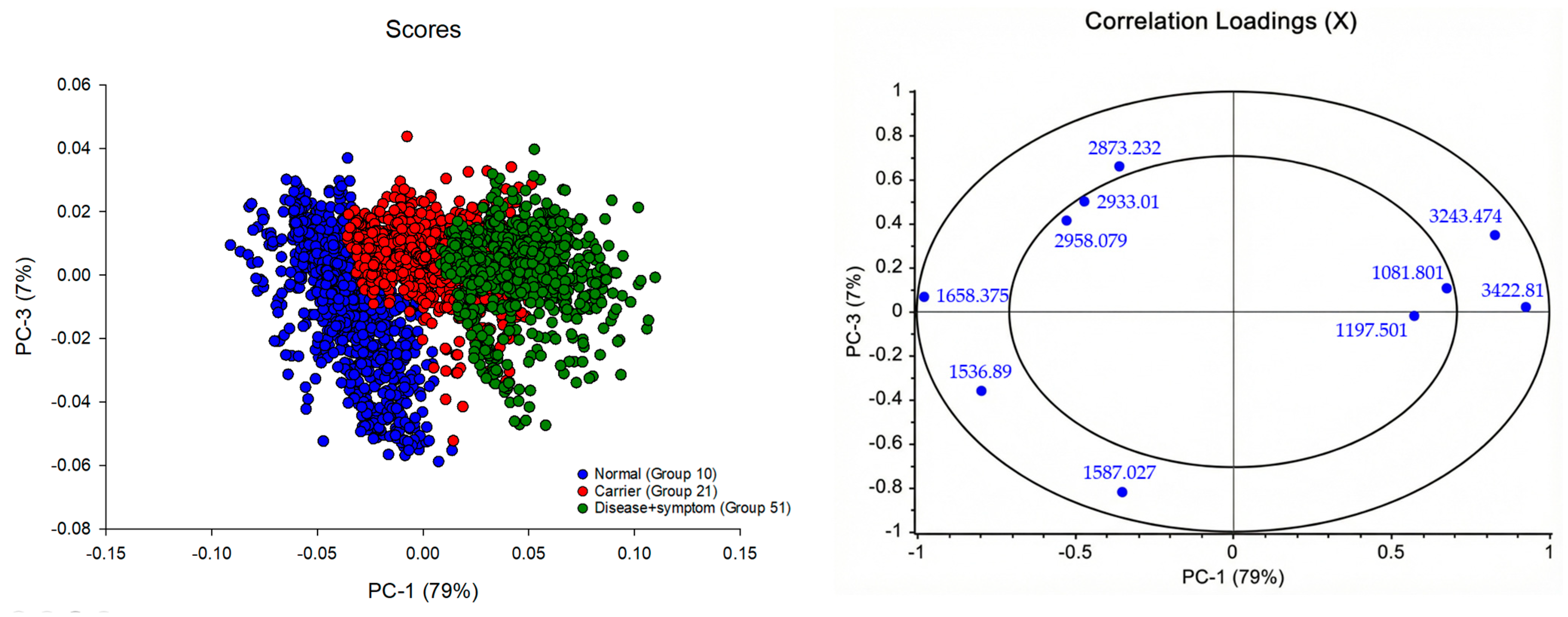

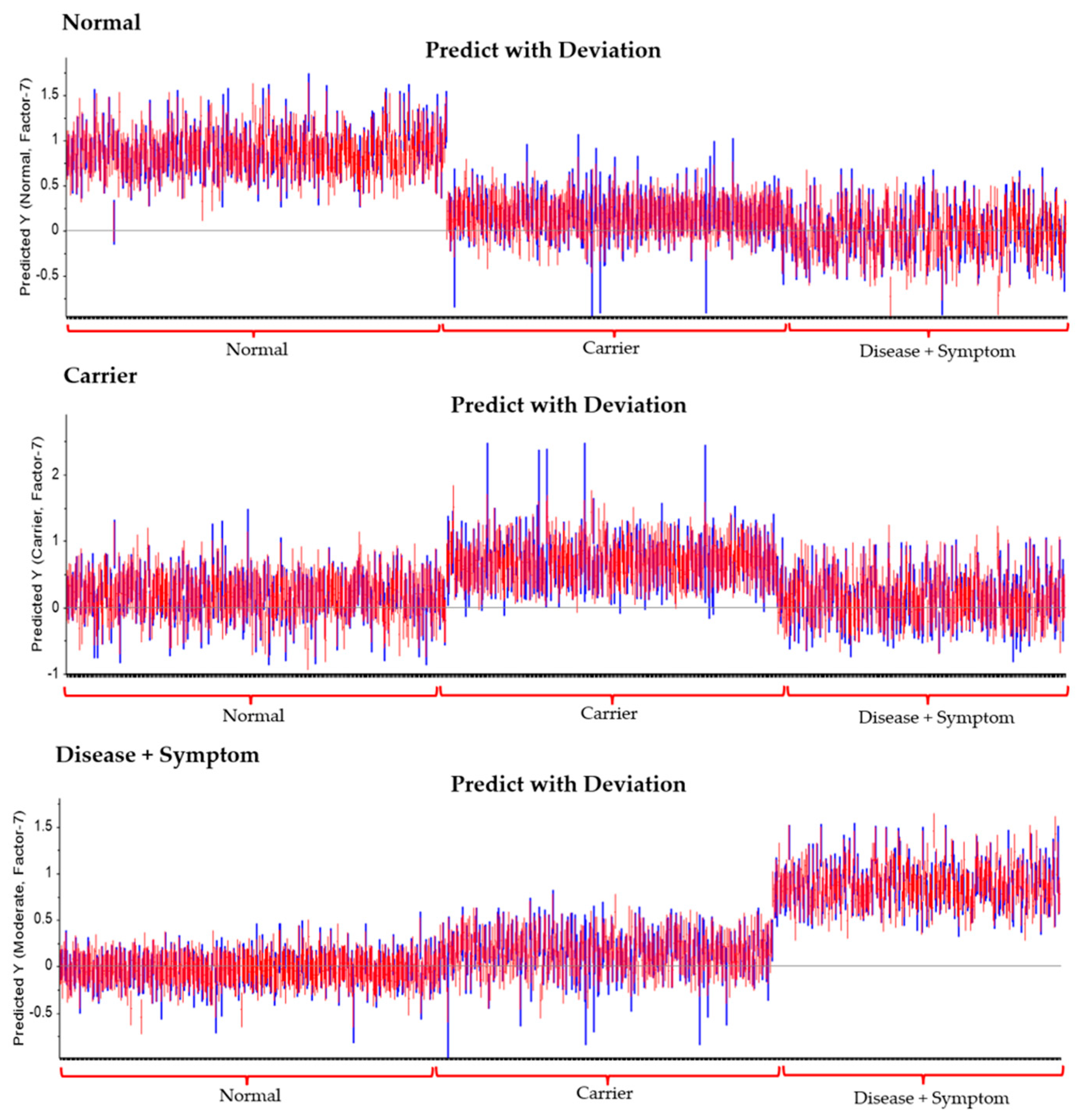

3.4. Correlation Loadings Analysis of PCA from FTIR Spectra of Hb Lysate

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baker, M.J.; Trevisan, J.; Bassan, P.; Bhargava, R.; Butler, H.J.; Dorling, K.M.; Fielden, P.R.; Fogarty, S.W.; Fullwood, N.J.; Heys, K.A.; et al. Using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy to analyze biological materials. Nat. Protoc. 2014, 9, 1771–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fucharoen, S.; Winichagoon, P. Haemoglobinopathies in Southeast Asia. Indian J. Med. Res. 2011, 134, 498–506. [Google Scholar]

- Harnsajarupant, P. Thalassemia. Jetanin Acad. J. 2023, 10. Available online: https://jetanin.com/th (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- MedlinePlus. Alpha Thalassemia. 2023. Available online: https://3billion.io/blog/rare-disease-series-3-thalassemia/ (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- Wasi, P.; Pootrakul, S.; Pootrakul, P.; Pravatmuang, P.; Initiator, P.; Fucharoen, S. Thalassemia in Thailand. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1980, 344, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berzal, F. Redes Neuronales & Deep Learning; Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chonat, S.; Quinn, C.T. Current standards of care and long-term outcomes for thalassemia and sickle cell disease. In Gene and Cell Therapies for Beta-Globinopathies. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Malik, P., Tisdale, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 1013. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchaisuriya, K.; Fucharoen, G.; Sae-Ung, N.; Sae-Ue, N.; Baisungneon, R.; Jetsrisuparb, A.; Fucharoen, S. Molecular and hematological characterization of HbE heterozygote with alpha-thalassemia determinant. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 1997, 28, 100–103. [Google Scholar]

- Thumanu, K.; Tanthanuch, W.; Ye, D.; Sangmalee, A.; Lorthongpanich, C.; Heraud, P.; Parnpai, R. Spectroscopic signature of mouse embryonic stem-cell–derived hepatocytes using synchrotron FTIR microspectroscopy. J. Biomed. Opt. 2011, 16, 057005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajwa, H.; Basit, H. Thalassemia. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Movasaghi, Z.; Rehman, S.; Rehman, I.U. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy of biological tissues. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2008, 43, 134–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, H.J.; Cameron, J.M.; Jenkins, C.A.; Hithell, G.; Hume, S.; Hunt, N.T.; Baker, M.J. Shining a light on clinical spectroscopy: Translation of diagnostic IR, 2D-IR and Raman spectroscopy towards the clinic. Clin. Spectrosc. 2019, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukiatsiri, S.; Siriwong, S.; Thumanu, K. Pupae protein extracts exert anticancer effects by down-regulating IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α via biomolecular changes in human breast cancer cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 128, 110278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruyne, S.; Speeckaert, M.M.; Delanghe, J.R. Applications of mid-infrared spectroscopy in the clinical laboratory setting. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2017, 55, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkhunthod, B.; Chira-atthakit, B.; Chitsomboon, B.; Kiatsongchai, R.; Thumanu, K.; Musika, S.; Sittisart, P. Apoptotic induction of the water fraction of Pseuderanthemum palatiferum ethanol-extract powder in Jurkat cells monitored by FTIR microspectroscopy. ScienceAsia 2021, 47, 556–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dybas, J.; Alcicek, F.C.; Wajda, A.; Kaczmarska, M.; Zimna, A.; Bulat, K.; Marzec, K.M. Trends in biomedical analysis of red blood cells—Raman spectroscopy versus other spectroscopic, microscopic and classical techniques. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2022, 146, 116481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadlelmoula, A.; Pinho, D.; Carvalho, V.H.; Catarino, S.O.; Minas, G. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy to analyse human blood over the last 20 years: A review towards lab-on-a-chip devices. Micromachines 2022, 13, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlayson, D.; Rinaldi, C.; Baker, M.J. Is infrared spectroscopy ready for the clinic? Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 12117–12128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Wei, G.; Chen, W.; Lei, C.; Xu, C.; Guan, Y.; Liu, H. Fast and deep diagnosis using blood-based ATR-FTIR spectroscopy for digestive tract cancers. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaimuangpak, K.; Tamprasit, K.; Thumanu, K.; Weerapreeyakul, N. Extracellular vesicles derived from microgreens of Raphanus sativus L. var. caudatus Alef contain bioactive macromolecules and inhibit HCT116 cell proliferation. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 15686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochan, K.; Bedolla, D.E.; Perez-Guaita, D.; Adegoke, J.A.; Veettil, T.C.P.; Martin, M.; Wood, B.R. Infrared spectroscopy of blood. Appl. Spectrosc. 2020, 75, 611–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mistek-Morabito, E.; Lednev, I.K. FT-IR spectroscopy for identification of biological stains for forensic purposes. Spectroscopy 2018, 33, 8–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mostaço-Guidolin, L.B.; Bachmann, L. Application of FTIR spectroscopy for identification of blood and leukemia biomarkers: A review over the past 15 years. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2011, 46, 388–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remanan, S.; Rajeev, P.; Sukumaran, K.; Savithri, S. Robustness of FTIR-based ultrarapid COVID-19 diagnosis using PLS-DA. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 47357–47371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoto, F.; Martimort, P.; Drusch, M. Selecting and interpreting measures of thematic classification accuracy. Remote Sens. Environ. 1997, 62, 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Thumanu, K.; Sangrajrang, S.; Khuhaprema, T.; Kalalak, A.; Tanthanuch, W.; Pongpiachan, S.; Heraud, P. Diagnosis of liver cancer from blood sera using FTIR microspectroscopy: A preliminary study. J. Biophotonics 2014, 7, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Wang, Y. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy in oral cancer diagnosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breiman, L. Bagging predictors. Mach. Learn. 1996, 24, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferih, K.; Elsayed, B.; Elshoeibi, A.M.; Elsabagh, A.A.; Elhadary, M.; Soliman, A.; Abdalgayoom, M.; Yassin, M. Applications of artificial intelligence in thalassemia: A comprehensive review. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammut, C.; Webb, G.I. (Eds.) Encyclopedia of Machine Learning; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 1–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Aksoy, C.; Uckan, D.; Severcan, F. FTIR spectroscopic imaging of mesenchymal stem cells in beta thalassemia major disease state. Biomed. Spectrosc. Imaging 2012, 1, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.-Z.; Tsang, K.; Li, C.; Shaw, A.; Mantsch, H. Infrared spectroscopic identification of beta-thalassemia. Clin. Chem. 2003, 49, 1125–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.X.; Wang, G.W.; Yao, H.L.; Huang, S.S.; Wang, Y.B.; Tao, Z.H.; Li, Y.Q. FTIR-HATR to identify beta-thalassemia and its mechanism study. Guang Pu Xue Yu Guang Pu Fen Xi 2009, 29, 1232–1236. [Google Scholar]

- Sukpong, S.; Thumanu, K.; Saovana, T.; Siriwong, S.; Changlek, S. Application of infrared spectroscopy for classification of thalassemia and hemoglobin E. Suranaree J. Sci. Technol. 2018, 25, 191–200. [Google Scholar]

- Derczynski, L. Complementarity, F-score, and NLP evaluation. In Proceedings of the Language Resources and Evaluation Conference, Portorož, Slovenia, 23–28 May 2016; Volume 2016, pp. 261–266. [Google Scholar]

- Devore, J.L. Probability and Statistics for Engineering and the Sciences; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Efron, B. Bootstrap methods: Another look at the jackknife. Ann. Stat. 1979, 7, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, T. An introduction to ROC analysis. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2006, 27, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohavi, R. A study of cross-validation and bootstrap for accuracy estimation and model selection. In Proceedings of the Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–25 August 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Metz, C.E. Basic principles of ROC analysis. Semin. Nucl. Med. 1978, 8, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, D.M.W. Evaluation: From precision, recall and F-factor to ROC, informed ness, markedness & correlation. J. Mach. Learn. Technol. 2007, 2, 37–63. [Google Scholar]

- Raschka, S. Model evaluation, model selection, and algorithm selection in machine learning. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1811.12808. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, T.; Rehmsmeier, M. The precision-recall plot is more informative than the ROC plot for imbalanced datasets. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, Y. The Truth of the F-Measure; School of Computer Science, University of Manchester: Manchester, UK, 2007; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Srisongkram, T.; Weerapreeyakul, N.; Thumanu, K. Evaluation of melanoma (SK-MEL-2) cell growth between 3D and 2D cell cultures with FTIR microspectroscopy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.R. An Introduction to Error Analysis; University Science Books: Sausalito, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Tharwat, A. Classification assessment methods. Appl. Comput. Inform. 2018, 17, 168–192; pp. 1–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherall, D.J.; Clegg, J.B. The Thalassemia Syndromes, 4th ed.; Blackwell Science: Bognor Regis, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for the Control of Haemoglobin Disorders; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tantiworawit, A.; Winichakoon, P.; Rattanathammethee, T.; Hantrakool, S.; Chai-Adisaksopha, C.; Rattarittamrong, E.; Norasetthada, L.; Charoenkwan, P.; Fanhchaksai, K.; Srichairatanakool, S.; et al. Molecular characteristics of thalassemia and hemoglobin variants in prenatal diagnosis program in Northern Thailand. Int. J. Hematol. 2019, 110, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongprasert, F.; Sirichotiyakul, S.; Piyamongkol, W.; Tongsong, T. Sensitivity and specificity of simple erythrocyte osmotic fragility test for screening of alpha-thalassemia-1 and beta-thalassemia trait in pregnant women. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2010, 69, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Goodacre, R. On splitting training and validation set: A comparative study of cross-validation, bootstrap and systematic sampling for estimating generalization. J. Anal. Test. 2018, 2, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krimm, S.; Bandekar, J. Vibrational spectroscopy and conformation of peptides, polypeptides, and proteins. Adv. Protein Chem. 1986, 38, 181–364. [Google Scholar]

- Surewicz, W.K.; Mantsch, H.H.; Chapman, D. Determination of protein secondary structure by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy: A critical assessment. Biochemistry 1993, 32, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, M.J.; Fellous, T.G.; Hammiche, A.; Lin, W.R.; Fullwood, N.J.; Grillo-Hill, B.K.; Jimenez, B.; Polyak, K.; Martin-Hirsch, P.L.; Nicholson, J.K.; et al. Fourier transform infrared microspectroscopy identifies symmetric PO2-modifications as a marker of the putative stem cell region of human intestinal crypts. Stem Cells 2008, 26, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, A. Infrared spectroscopy of proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)–Bioenerg 2007, 1767, 1073–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meutter, J.; Goormaghtigh, E. Evaluation of Protein Secondary Structure from FTIR Spectra Improved after Partial Deuteration. Anal. Biochem. 2021, 625, 114206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, E.J.; Krimm, S.; Miller, W.G. Infrared spectra and assignments for the amide I band in polypeptides. Biopolymers 1993, 33, 1741–1752. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, J.; Yu, S. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopic Analysis of Protein Secondary Structures. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2007, 39, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, G.; Witten, D.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. An Introduction to Statistical Learning; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, H.; Shi, H.; Dong, A.; Wang, L.; Yu, S. Progress in Infrared Spectroscopy as an Efficient Tool for Predicting Protein Secondary Structure. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2022, 268, 120604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Group | Phenotype | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Normal | 10 | Normal |

| Alpha-thal 2 hetero | 22 | Alpha-thalassemia 2 heterozygote | |

| Others-1 | 25 | Hb Constant Spring or Hb Paksaé heterozygote | |

| Carrier | Alpha | 21 | Alpha-thalassemia 1 heterozygote |

| 24 | Compound Alpha-thalassemia 2 heterozygote | ||

| 45 | Hb E heterozygote with Alpha-thal 2 heterozygote | ||

| Beta | 31 | Beta (0)-thalassemia heterozygote | |

| 34 | Beta (+)-thalassemia heterozygote | ||

| HbE hetero | 32 | Hb E heterozygote | |

| HbE hetero with Alpha | 44 | Hb E heterozygote with Alpha-thalassemia 1 heterozygote | |

| Others-2 | 39 | Hb E heterozygote with Alpha-thalassemia 2 heterozygote | |

| Disease | HbE homo | 33 | Hb E homozygote |

| HbE homo with Alpha | 47 | Hb E homozygote with Alpha-thalassemia 1 heterozygote | |

| HbH | 51 | Hb H Disease | |

| Others-3 | 89 | EA Bart’s Disease |

| Wavenumber (cm−1) | Assignments | Molecular Vibration of Functional Group | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3290 | Amide A | N-H Stretching | [53] |

| 3050 | Amide B | N-H Stretching | [53] |

| 3000 | Protein side chains | Symmetric and asymmetric of CH2 | [54] |

| 2875 | Protein side chains | stretching vibrations of CH3 | [54] |

| 1600–1700 | Amide I | C=O Stretching | [55] |

| 1500–1600 | Amide II | N-H Bending | [55,56,57,58,59] |

| 1452 | Amino acids in the protein side chains | Bending vibrations of CH2: δ (CH2) | [60] |

| 1387 | Amino acids in the protein side chains | Bending vibrations of CH3: δ(CH3) | [60] |

| 1240–1220 | Amide III Protein secondary structure | C–N stretch + N–H bending | [56] |

| 1084–1090 | protein side chains/glycoprotein-related vibration | C–O stretching | [23,56,61] |

| 830–750 | Aromatic residues marker | Aromatic ring breathing (Tyr, Phe) | [56] |

| Group | Statistics | No. Vigor | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | True positive | 378 | 0.98 | 0.99 |

| False Positive | 6 | |||

| Carrier | True positive | 272 | 0.81 | 0.91 |

| False Positive | 62 | |||

| Disease + Symptom | True positive | 287 | 0.99 | 1.00 |

| False Positive | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Thumanu, K.; Khamgasem, T.; Sukpong, S.; Phatthanakun, R.; Puangplruk, R.; Tanthanuch, W.; Kuaprasert, B.; Tastub, S.; Rujanakraikarn, R.; Tun, S.; et al. A New Method for Screening Thalassemia Patients Using Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010067

Thumanu K, Khamgasem T, Sukpong S, Phatthanakun R, Puangplruk R, Tanthanuch W, Kuaprasert B, Tastub S, Rujanakraikarn R, Tun S, et al. A New Method for Screening Thalassemia Patients Using Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(1):67. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010067

Chicago/Turabian StyleThumanu, Kanjana, Tanaporn Khamgasem, Somsamorn Sukpong, Rungrueang Phatthanakun, Rawiwan Puangplruk, Waraporn Tanthanuch, Buabarn Kuaprasert, Sukanya Tastub, Roengrut Rujanakraikarn, Saitip Tun, and et al. 2026. "A New Method for Screening Thalassemia Patients Using Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy" Diagnostics 16, no. 1: 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010067

APA StyleThumanu, K., Khamgasem, T., Sukpong, S., Phatthanakun, R., Puangplruk, R., Tanthanuch, W., Kuaprasert, B., Tastub, S., Rujanakraikarn, R., Tun, S., Saovana, T., Munkongdee, T., & Wongthong, S. (2026). A New Method for Screening Thalassemia Patients Using Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy. Diagnostics, 16(1), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010067