Early Detection of Cystoid Macular Edema in Retinitis Pigmentosa Using Longitudinal Deep Learning Analysis of OCT Scans

Abstract

1. Introduction

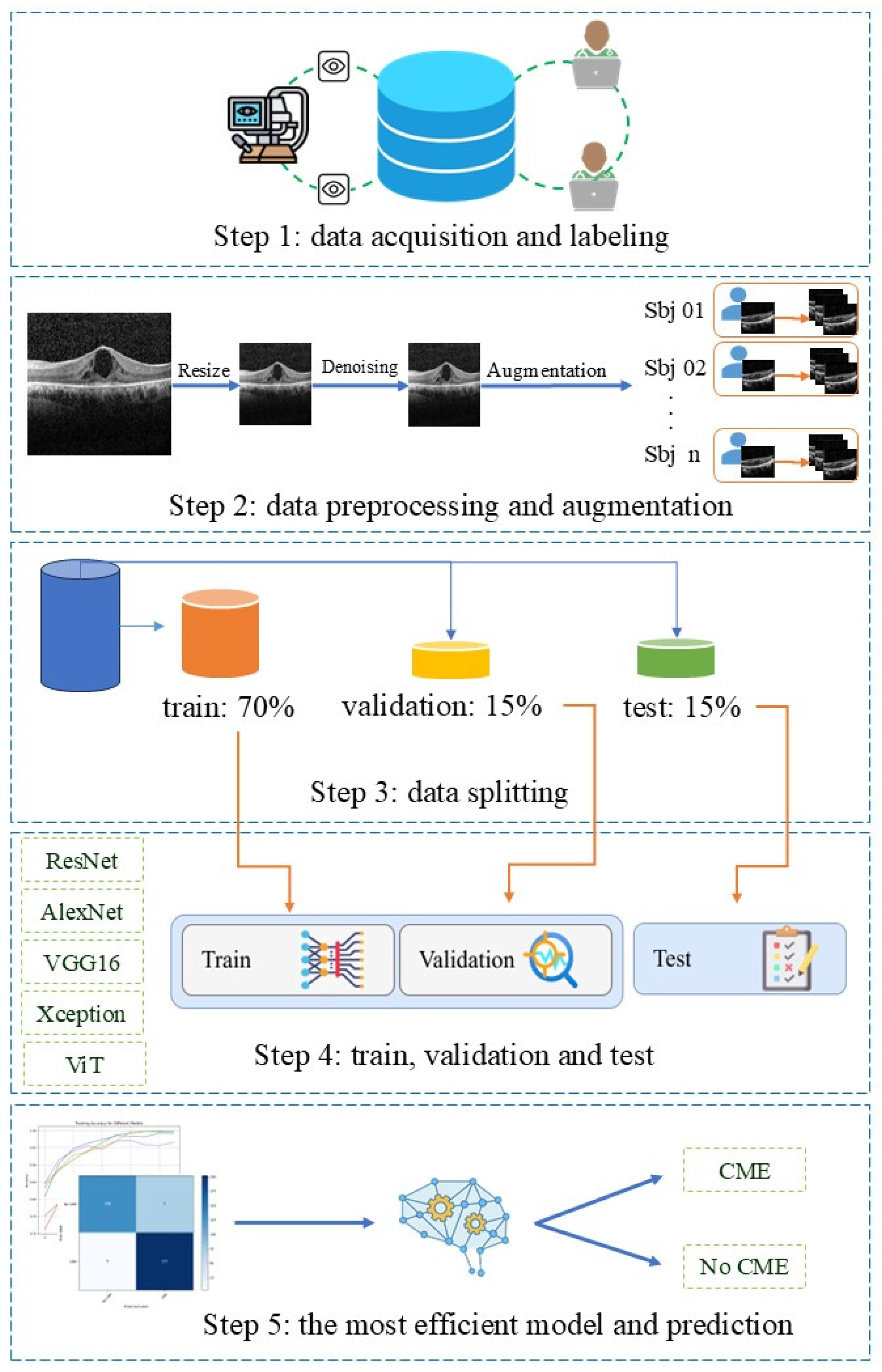

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Set

2.2. Data Preparation

2.3. Deep Learning Models

| Model | Architectural Characteristics | Rationale for Inclusion |

|---|---|---|

| ResNet-18/ResNet-34 | Residual blocks, identity skip connections, stable deep training | Most widely used OCT classifiers, robust to overfitting, strong performance in CME/DME tasks |

| VGG16 | Deep sequential 3 × 3 conv blocks, high parameter count | Classical OCT baseline; widely used for transfer learning on OCT |

| AlexNet | Early CNN with large initial filters, shallow architecture | Lightweight baseline, useful historical benchmark in OCT literature |

| Xception | Depthwise-separable convolutions, efficient feature extraction | Strong performance with limited OCT data, captures localized retinal patterns efficiently |

| ViT | Patch embeddings + self-attention, global context modeling | Modern architecture; relevant to OCT where global spatial relations matter, emerging in ophthalmology |

2.4. Performance Evaluation and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. This Patient and Imaging Characteristics

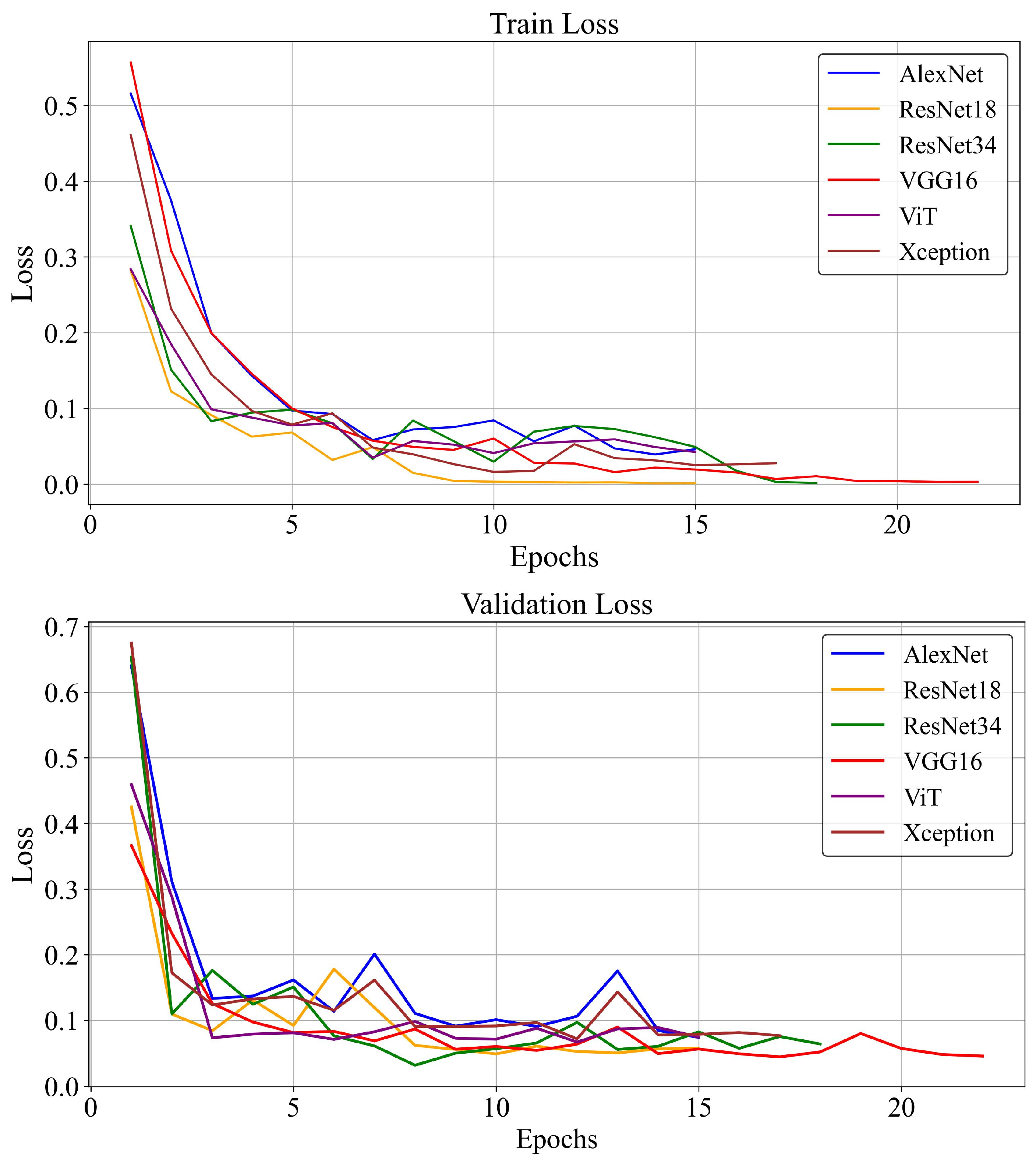

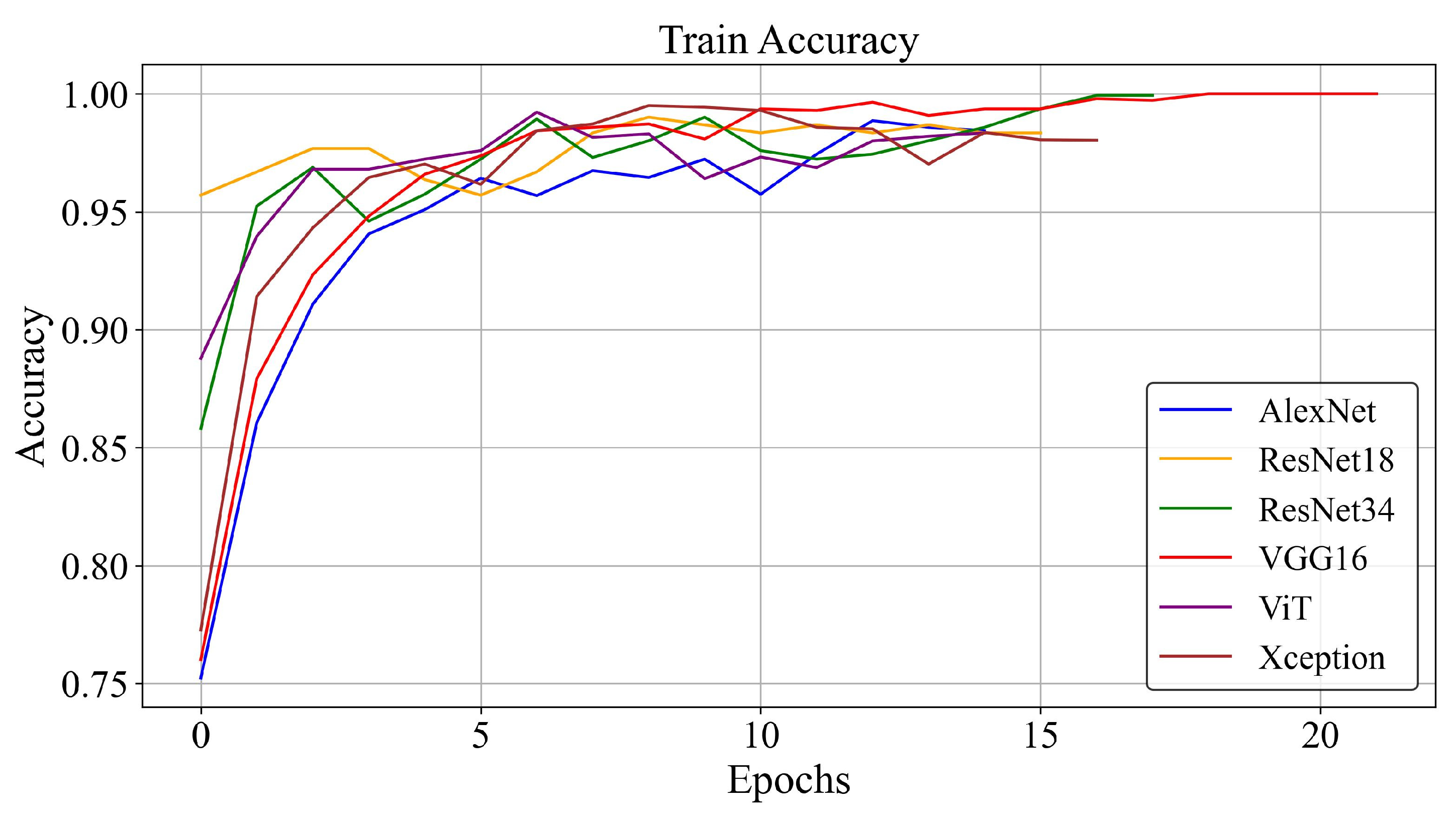

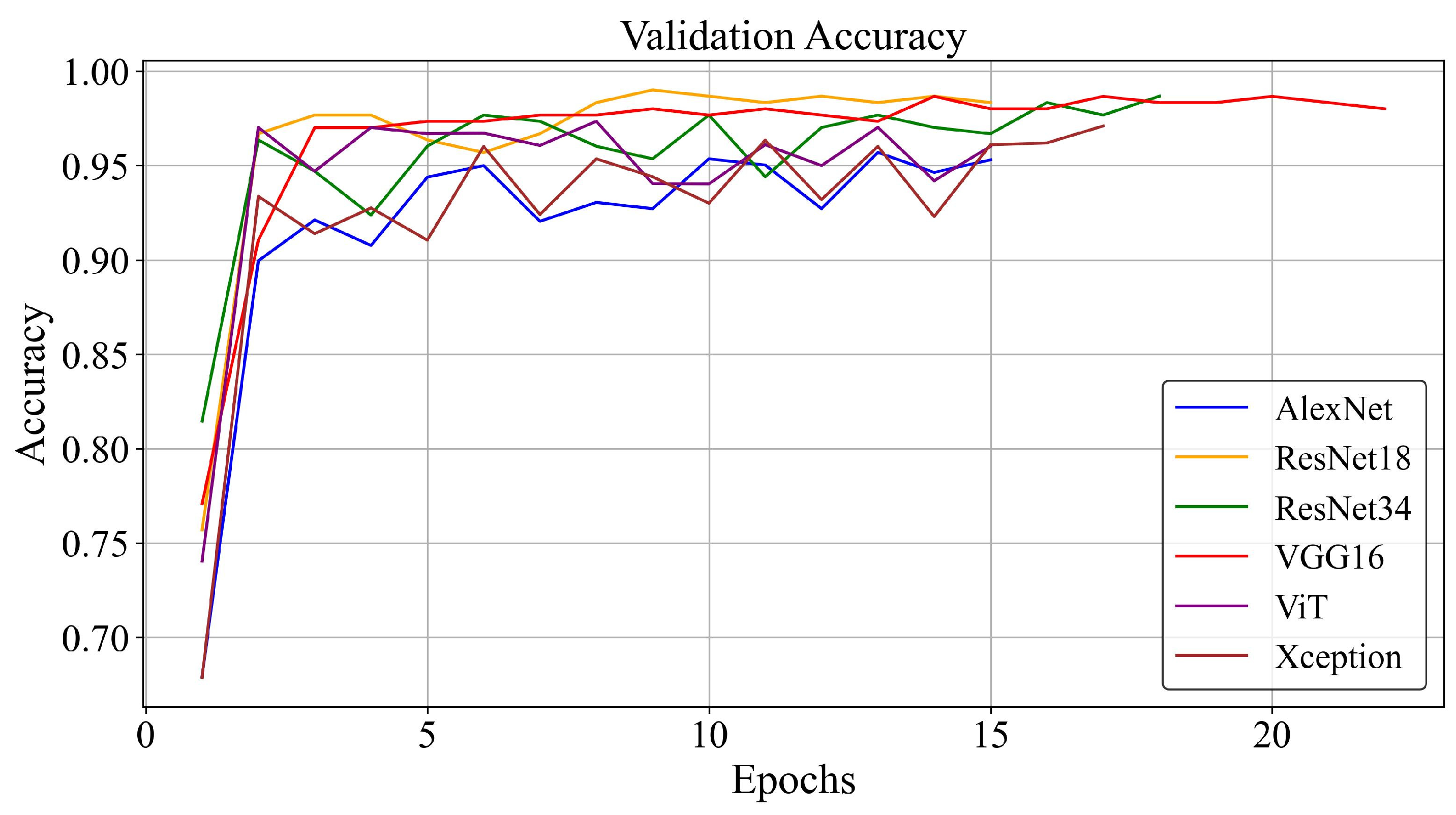

3.2. Training Loss and Accuracy

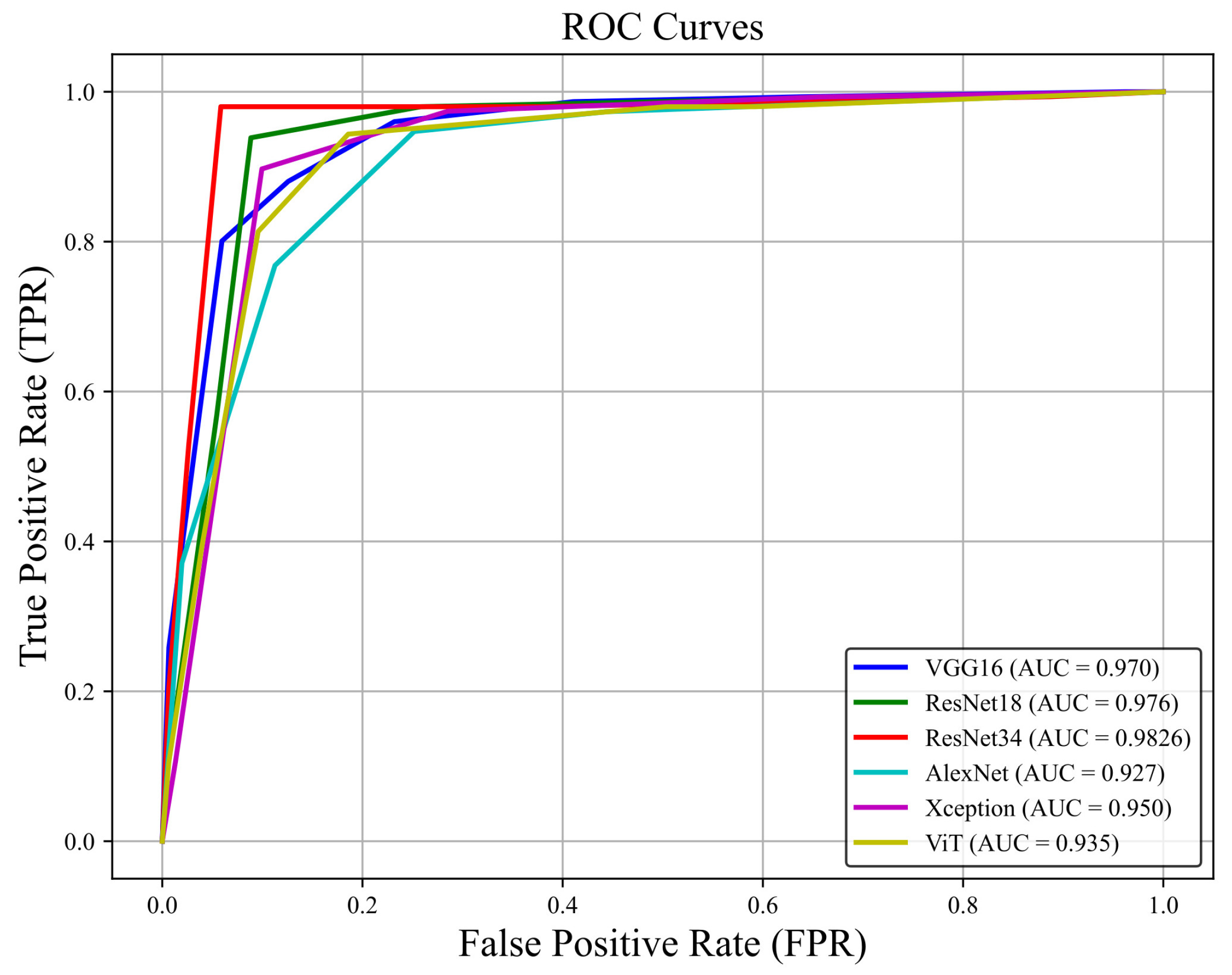

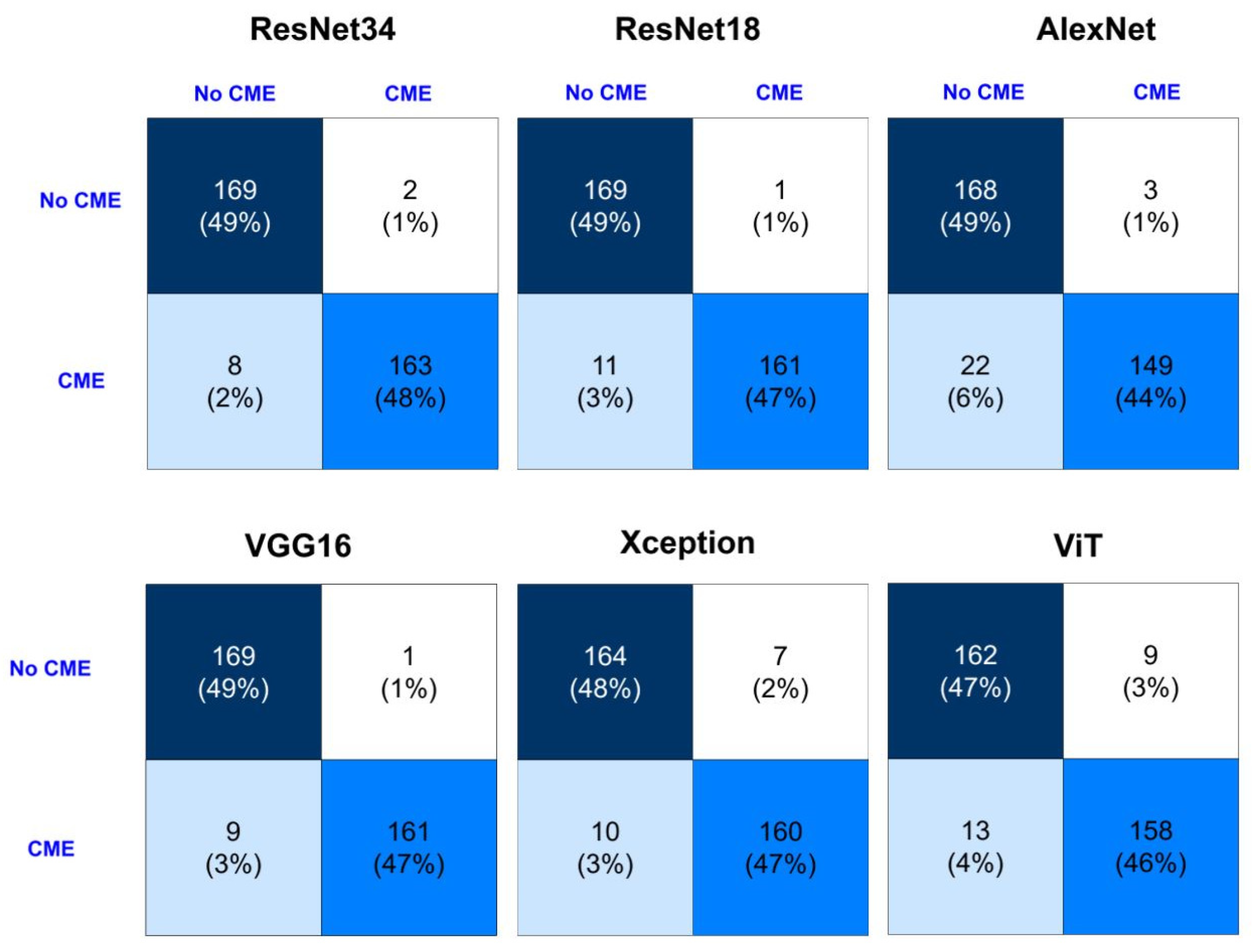

3.3. Detection Performance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OCT | Optical Coherence Tomography |

| RP | Retinitis Pigmentosa |

| CME | Cystoid Macular Edema |

| SD-OCT | Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| ViT | Vision Transformer |

| AUROC/AUC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve |

| TP | True Positive |

| FP | False Positive |

| TN | True Negative |

| FN | False Negative |

| IRDReg® | Iranian National Registry for Inherited Retinal Diseases |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| xAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

| AR | Augmented Reality |

References

- Sayo, A.; Ueno, S.; Kominami, T.; Nishida, K.; Inooka, D.; Nakanishi, A.; Yasuda, S.; Okado, S.; Takahashi, K.; Matsui, S.; et al. Longitudinal study of visual field changes determined by Humphrey Field Analyzer 10-2 in patients with Retinitis Pigmentosa. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrigo, A.; Aragona, E.; Perra, C.; Bianco, L.; Antropoli, A.; Saladino, A.; Berni, A.; Basile, G.; Pina, A.; Bandello, F.; et al. Characterizing macular edema in retinitis pigmentosa through a combined structural and microvascular optical coherence tomography investigation. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.C.; Lim, W.S.; Wang, V.Y.; Ko, M.L.; Chiu, S.I.; Huang, Y.S.; Lai, F.; Yang, C.M.; Hu, F.R.; Jang, J.R.; et al. Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Early Detection of Retinitis Pigmentosa—The Most Common Inherited Retinal Degeneration. J. Digit. Imaging 2021, 34, 948–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias, J.D.; Kalaw, F.G.P.; Alex, V.; Yassin, S.H.; Ferreyra, H.; Walker, E.; Wagner, N.E.; Borooah, S. Investigating the associations of macular edema in retinitis pigmentosa. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markomichelakis, N.N.; Halkiadakis, I.; Pantelia, E.; Peponis, V.; Patelis, A.; Theodossiadis, P.; Theodossiadis, G. Patterns of macular edema in patients with uveitis: Qualitative and quantitative assessment using optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology 2004, 111, 946–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Liu, X.; Peng, X. Management of Cystoid Macular Edema in Retinitis Pigmentosa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 895208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, G.; Strong, S.; Bradley, P.; Severn, P.; Moore, A.T.; Webster, A.R.; Mitchell, P.; Kifley, A.; Michaelides, M. Prevalence of cystoid macular oedema, epiretinal membrane and cataract in retinitis pigmentosa. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 103, 1163–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.K.; Nuzbrokh, Y.; Lima de Carvalho, J.R., Jr.; Ryu, J.; Tsang, S.H. Optical coherence tomography in the evaluation of retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmic Genet. 2020, 41, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruff, A.; Tezel, A.; Tezel, T.H. Anatomical and functional correlates of cystic macular edema in retinitis pigmentosa. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimokawa, S.; Fujiwara, K.; Murakami, Y.; Funatsu, J.; Nakatake, S.; Yoshida, N.; Sonoda, K.-H.; Ikeda, Y. Effect of topical dorzolamide on cystoid macular edema in retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmol. Retin. 2020, 4, 1036–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitahata, S.; Gocho, K.; Motozawa, N.; Yokota, S.; Yamamoto, M.; Maeda, A.; Hirami, Y.; Kurimoto, Y.; Kadonosono, K.; Takahashi, M. Evaluation of photoreceptor features in retinitis pigmentosa with cystoid macular edema by using an adaptive optics fundus camera. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0296493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.J.; Joe, S.G.; Lee, D.-H.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, J.-G.; Yoon, Y.H. Correlations between spectral-domain OCT measurements and visual acuity in cystoid macular edema associated with retinitis pigmentosa. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013, 54, 1303–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousavi, N.; Monemian, M.; Ghaderi Daneshmand, P.; Mirmohammadsadeghi, M.; Zekri, M.; Rabbani, H. Cyst identification in retinal optical coherence tomography images using hidden Markov model. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhang, B.; Hu, Y.; Liu, B.; Cao, D.; Yang, D.; Peng, Q.; Zhong, P.; Zeng, X.; Xiao, Y.; et al. Detection of morphologic patterns of diabetic macular edema using a deep learning approach based on optical coherence tomography images. Retina 2021, 41, 1110–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Miguel, A.; Arruabarrena, C.; Allendes, G.; Olivera, M.; Zarranz-Ventura, J.; Teus, M.A. Hybrid deep learning models for the screening of Diabetic Macular Edema in optical coherence tomography volumes. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Wan, Z.; Li, P.; Chen, L.; Wang, J.; Fan, Y.; Chen, X.; Peng, Q.; Gao, P. Accuracy and feasibility with AI-assisted OCT in retinal disorder community screening. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 1053483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouhollahi, A.; Homaei, A.; Sahu, A.; Harari, R.E.; Nezami, F.R. Ragnosis: Retrieval-augmented generation for enhanced medical decision making. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harari, R.; Rajabzadeh-Oghaz, H.; Hosseini, F.; Shali, M.G.; Altaweel, A.; Haouchine, N.; Rikhtegar, F. CMANet: Cross-Modal Attention Network for 3-D Knee MRI and Report-Guided Osteoarthritis Assessment. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, F.; Asadi, F.; Rabiei, R.; Kiani, F.; Harari, R.E. Applications of artificial intelligence in diagnosis of uncommon cystoid macular edema using optical coherence tomography imaging: A systematic review. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2024, 69, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viedma, I.A.; Alonso-Caneiro, D.; Read, S.A.; Collins, M.J. Deep learning in retinal optical coherence tomography (OCT): A comprehensive survey. Neurocomputing 2022, 507, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, G.A.; Batouty, N.M.; Haggag, S.; Elnakib, A.; Khalifa, F.; Taher, F.; Mohamed, M.A.; Farag, R.; Sandhu, H.; Sewelam, A.; et al. The role of medical image modalities and AI in the early detection, diagnosis and grading of retinal diseases: A survey. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, U.P.S.; Surico, P.L.; Singh, R.B.; Romano, F.; Salati, C.; Spadea, L.; Musa, M.; Gagliano, C.; Mori, T.; Zeppieri, M. Artificial intelligence (AI) for early diagnosis of retinal diseases. Medicina 2024, 60, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, F.; Rafizadeh, S.M.; Fakhredin, H.; Rajabi, M.T.; Yaseri, M.; Hosseini, F.; Fekrazad, R.; Salari, B. Prediction of substantial closed-globe injuries in orbital wall fractures. Int. Ophthalmol. 2024, 44, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, C.; Wang, L.; Wang, G.; Lv, B.; Lv, C.; Xie, G.; Wang, F. Evaluation of an OCT-AI-Based Telemedicine Platform for Retinal Disease Screening and Referral in a Primary Care Setting. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2022, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manikandan, S.; Raman, R.; Rajalakshmi, R.; Tamilselvi, S.; Surya, R.J. Deep learning–based detection of diabetic macular edema using optical coherence tomography and fundus images: A meta-analysis. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 71, 1783–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leandro, I.; Lorenzo, B.; Aleksandar, M.; Dario, M.; Rosa, G.; Agostino, A.; Daniele, T. OCT-based deep-learning models for the identification of retinal key signs. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altan, G. DeepOCT: An explainable deep learning architecture to analyze macular edema on OCT images. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2022, 34, 101091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Wang, X.; Ran, A.-r.; Chan, C.K.; Ho, M.; Yip, W.; Young, A.L.; Lok, J.; Szeto, S.; Chan, J.; et al. A multitask deep-learning system to classify diabetic macular edema for different optical coherence tomography devices: A multicenter analysis. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, 2078–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Choe, S.; Wy, S.; Jang, M.; Jeoung, J.W.; Choi, H.J.; Park, K.H.; Sun, S.; Kim, Y.K. Demographics Prediction and Heatmap Generation From OCT Images of Anterior Segment of the Eye: A Vision Transformer Model Study. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2022, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, N.; Abdel Wahed, M.; Salaheldin, A.M. Transfer learning-based platform for detecting multi-classification retinal disorders using optical coherence tomography images. Int. J. Imaging Syst. Technol. 2022, 32, 740–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, F.; Wu, F.P.; Zhong, Y.L. Artificial intelligence method based on multi-feature fusion for automatic macular edema (ME) classification on spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) images. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1097291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Fu, Y.-L.; Zhu, D. ResNet and its application to medical image processing: Research progress and challenges. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2023, 240, 107660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbaghi, H.; Daftarian, N.; Suri, F.; Mirrahimi, M.; Madani, S.; Sheikhtaheri, A.; Khorrami, F.; Saviz, P.; Nejad, M.Z.; Tivay, A.; et al. The first inherited retinal disease registry in Iran: Research protocol and results of a pilot study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 23, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badar, M.; Haris, M.; Fatima, A. Application of deep learning for retinal image analysis: A review. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2020, 35, 100203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalithadevi, B.; Krishnaveni, S. Detection of diabetic retinopathy and related retinal disorders using fundus images based on deep learning and image processing techniques: A comprehensive review. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2022, 34, e7032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Bai, L.; Zhang, S.; Mou, X. A preliminary study of predicting effectiveness of anti-VEGF injection using OCT images based on deep learning. In Proceedings of 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering In Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 July 2020; pp. 5428–5431. [Google Scholar]

- Sotoudeh-Paima, S.; Jodeiri, A.; Hajizadeh, F.; Soltanian-Zadeh, H. Multi-scale convolutional neural network for automated AMD classification using retinal OCT images. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 144, 105368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berthet, A.; Dugelay, J.-L. A review of data preprocessing modules in digital image forensics methods using deep learning. In Proceedings of 2020 IEEE International Conference on Visual Communications and Image Processing (VCIP), Macau, China, 1–4 December 2020; pp. 281–284. [Google Scholar]

- Kaothanthong, N.; Limwattanayingyong, J.; Silpa-Archa, S.; Tadarati, M.; Amphornphruet, A.; Singhanetr, P.; Lalitwongsa, P.; Chantangphol, P.; Amornpetchsathaporn, A.; Chainakul, M.; et al. The Classification of Common Macular Diseases Using Deep Learning on Optical Coherence Tomography Images with and without Prior Automated Segmentation. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, F.; Marques, M.J.; Gibson, S.J. Cystoid macular edema segmentation of optical coherence tomography images using fully convolutional neural networks and fully connected CRFs. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1709.05324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhlif, A.A.; Al-Khateeb, B.; Mohammed, M.A. An extensive review of state-of-the-art transfer learning techniques used in medical imaging: Open issues and challenges. J. Intell. Syst. 2022, 31, 1085–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kırık, F.; Demirkıran, B.; Aslanoğlu, C.E.; Koytak, A.; Özdemir, H. Detection and Classification of Diabetic Macular Edema with a Desktop-Based Code-Free Machine Learning Tool. Turk. J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 53, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-L.; Wu, K.-C. Development of revised ResNet-50 for diabetic retinopathy detection. BMC Bioinform. 2023, 24, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaheldin, A.M.; Abdel Wahed, M.; Talaat, M.; Saleh, N. Deep learning-based automated detection and grading of papilledema from OCT images: A promising approach for improved clinical diagnosis and management. Int. J. Imaging Syst. Technol. 2024, 34, e23133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rim, T.H.; Lee, A.Y.; Ting, D.S.; Teo, K.Y.C.; Yang, H.S.; Kim, H.; Lee, G.; Teo, Z.L.; Teo Wei Jun, A.; Takahashi, K.; et al. Computer-aided detection and abnormality score for the outer retinal layer in optical coherence tomography. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 106, 1301–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Z.; Panhwar, S.Q.; Baqai, A.; Umrani, F.A.; Ahmed, M.; Khan, A. Deep learning based automated detection of intraretinal cystoid fluid. Int. J. Imaging Syst. Technol. 2022, 32, 902–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.M.; Liu, X.; Nath, S.; Korot, E.; Faes, L.; Wagner, S.K.; Keane, P.A.; Sebire, N.J.; Burton, M.J.; Denniston, A.K. A global review of publicly available datasets for ophthalmological imaging: Barriers to access, usability, and generalisability. Lancet Digit. Health 2021, 3, e51–e66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Quy, T.; Roy, A.; Iosifidis, V.; Zhang, W.; Ntoutsi, E. A survey on datasets for fairness-aware machine learning. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2022, 12, e1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, F.; Asadi, F.; Emami, H.; Ebnali, M. Machine learning applications for early detection of esophageal cancer: A systematic review. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2023, 23, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassija, V.; Chamola, V.; Mahapatra, A.; Singal, A.; Goel, D.; Huang, K.; Scardapane, S.; Spinelli, I.; Mahmud, M.; Hussain, A. Interpreting black-box models: A review on explainable artificial intelligence. Cogn. Comput. 2024, 16, 45–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harari, R.; Al-Taweel, A.; Ahram, T.; Shokoohi, H. Explainable AI and Augmented Reality in Transesophageal Echocardiography (TEE) Imaging. In Proceedings of 2024 IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and eXtended and Virtual Reality (AIxVR), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 17–19 January 2024; pp. 306–309. [Google Scholar]

- Arrieta, A.B.; Díaz-Rodríguez, N.; Del Ser, J.; Bennetot, A.; Tabik, S.; Barbado, A.; García, S.; Gil-López, S.; Molina, D.; Benjamins, R.; et al. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): Concepts, taxonomies, opportunities and challenges toward responsible AI. Inf. Fusion 2020, 58, 82–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harari, R.E.; Altaweel, A.; Ahram, T.; Keehner, M.; Shokoohi, H. A randomized controlled trial on evaluating clinician-supervised generative AI for decision support. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2025, 195, 105701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harari, R.E.; Schulwolf, S.L.; Borges, P.; Salmani, H.; Hosseini, F.; Bailey, S.K.T.; Quach, B.; Nohelty, E.; Park, S.; Verma, Y.; et al. Applications of Augmented Reality for Prehospital Emergency Care: Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. JMIR XR Spat. Comput. 2025, 2, e66222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harari, R.E.; Altaweel, A.; Anderson, E.; Pozner, C.; Grossmann, R.; Goldsmith, A.; Shokoohi, H. Augmented Reality in Enhancing Operating Room Crisis Checklist Adherence: Randomized Comparative Efficacy Study. JMIR XR Spat. Comput. 2025, 2, e60792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harari, R.E.; Kian, C.; Ebnali-Heidari, M.; Mazloumi, A. User experience in immersive VR-based serious game: An application in highly automated driving training. In Proceedings of International Conference on Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics, Washington, DC, USA, 24–28 July 2019; pp. 133–144. [Google Scholar]

- Harari, R.E.; Paladugu, P.; Miccile, C.; Park, S.H.; Burian, B.; Yule, S.; Dias, R.D. Extended reality applications for space health. Aerosp. Med. Hum. Perform. 2023, 94, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harari, R.E.; Dias, R.D.; Kennedy-Metz, L.R.; Varni, G.; Gombolay, M.; Yule, S.; Salas, E.; Zenati, M.A. Deep learning analysis of surgical video recordings to assess nontechnical skills. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2422520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harari, R.; Smith, S.E.; Bahouth, S.M.; Lo, L.; Sury, M.; Yin, M.; Schaefer, L.F.; Wells, W.; Collins, J.; Duryea, J. Predicting Knee Osteoarthritis Progression Using Explainable Machine Learning and Clinical Imaging Data. SSRN 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, Z.; Harari, R.E.; Hole, G.; Kolb, B.E.; Mohajerani, M.H. Machine Learning Models Can Predict Tinnitus and Noise-Induced Hearing Loss. Ear Hear. 2025, 46, 1305–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Algorithm | Precision | Specificity | F1-Score | Recall | Accuracy | Optimizer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VGG16 | 0.9931 | 0.9934 | 0.9695 | 0.947 | 0.9702 | ADAM |

| Xception | 0.9595 | 0.9603 | 0.9498 | 0.9404 | 0.9503 | ADAM |

| ViT | 0.9259 | 0.9242 | 0.9363 | 0.946 | 0.9356 | SGD |

| AlexNet | 0.9778 | 0.9801 | 0.9231 | 0.8742 | 0.9272 | ADAM |

| ResNet-18 | 0.9821 | 0.9816 | 0.9804 | 0.9718 | 0.9765 | SGD = ADAM |

| ResNet-34 | 0.9943 | 0.9945 | 0.9836 | 0.9712 | 0.9868 | SGD = ADAM |

| Study | Objective | Dataset | AI Model(s) | Accuracy | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bai et al. (2022) [16] | AI-assisted auto-detection of 15 retinal disorders | 878 OCT scans | Deep learning-based AI model | 89.10% | AI-assisted OCT achieved high accuracy and was comparable to retina specialists in detecting multiple retinal disorders |

| Salaheldin et al. (2024) [44] | Automated detection and grading of papilledema from OCT images | OCT images of papilledema cases | SqueezeNet, AlexNet, GoogleNet, ResNet-50, Custom CNN | 98.50% | NA novel cascaded model combining multiple architectures for superior detection and grading of papilledema |

| Saleh et al. (2022) [30] | Multi-class classification of retinal disorders using OCT images | Public OCT dataset | Transfer learning-based platform | 98.40% | Achieved high accuracy across multiple retinal conditions |

| Kaothanthong et al. (2023) [39] | Comparison of DL-based OCT classification/segmentation | 14,327 OCT images from macular diseases | RelayNet, Graph-cut technique, and DL classification models | 94.80% | High accuracy with DL-based segmentation before classification |

| current study | Early detection of CME in RP patients | 2280 longitudinal OCT images from RP patients | ResNet-18, ResNet-34, Xception, AlexNet, Vision Transformer (ViT), VGG16 | 98.68% | ResNet models achieved the highest accuracy (98%) and specificity (99%) for early CME detection |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hosseini, F.; Asadi, F.; Rabiei, R.; Roshanpoor, A.; Sabbaghi, H.; Eslami, M.; Harari, R.E. Early Detection of Cystoid Macular Edema in Retinitis Pigmentosa Using Longitudinal Deep Learning Analysis of OCT Scans. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010046

Hosseini F, Asadi F, Rabiei R, Roshanpoor A, Sabbaghi H, Eslami M, Harari RE. Early Detection of Cystoid Macular Edema in Retinitis Pigmentosa Using Longitudinal Deep Learning Analysis of OCT Scans. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(1):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010046

Chicago/Turabian StyleHosseini, Farhang, Farkhondeh Asadi, Reza Rabiei, Arash Roshanpoor, Hamideh Sabbaghi, Mehrnoosh Eslami, and Rayan Ebnali Harari. 2026. "Early Detection of Cystoid Macular Edema in Retinitis Pigmentosa Using Longitudinal Deep Learning Analysis of OCT Scans" Diagnostics 16, no. 1: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010046

APA StyleHosseini, F., Asadi, F., Rabiei, R., Roshanpoor, A., Sabbaghi, H., Eslami, M., & Harari, R. E. (2026). Early Detection of Cystoid Macular Edema in Retinitis Pigmentosa Using Longitudinal Deep Learning Analysis of OCT Scans. Diagnostics, 16(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010046