Opportunistic Bone Health Assessment Using Contrast-Enhanced Abdominal CT: A DXA-Referenced Analysis in Liver Transplant Recipients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. CT Acquisition Protocol and HU Measurements

2.3. DXA Examination and Classification

2.4. Study Groups

2.5. Study Protocol, Ethical Approval, and Funding

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Entire Cohort

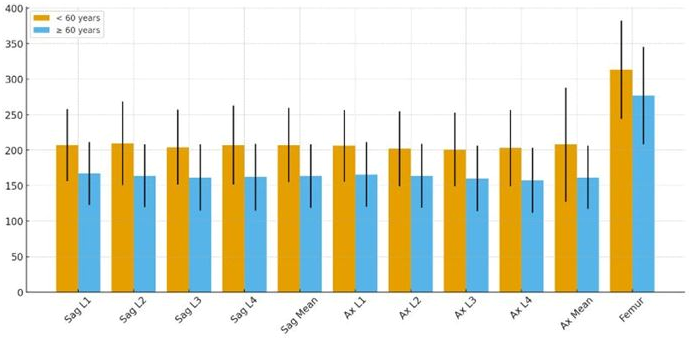

3.2. Quantitative CT Measurements and Age-Related Differences

3.3. Relationship Between HU Values and DXA-Based Bone Status

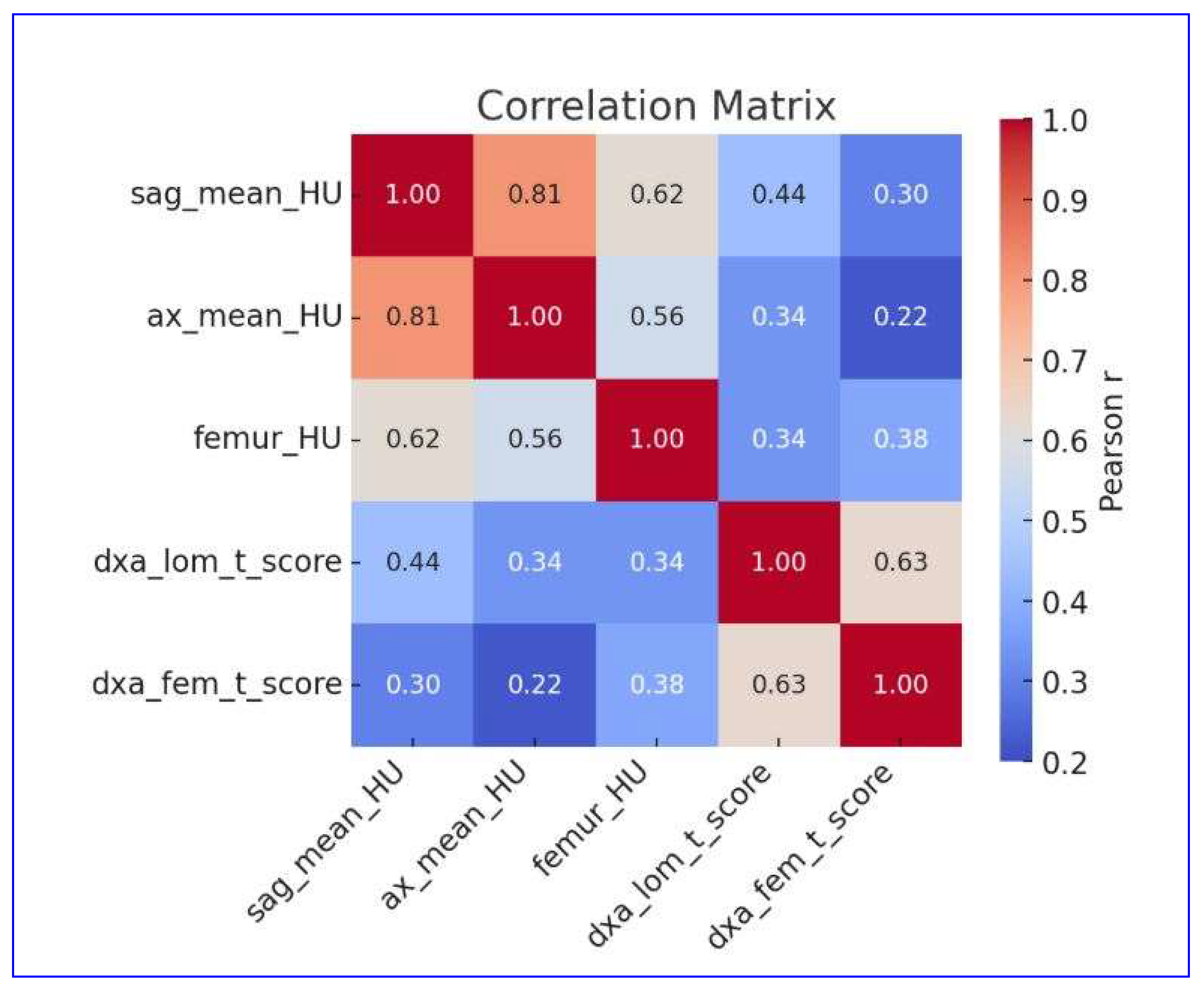

3.4. Correlation Between Quantitative CT and DXA Parameters

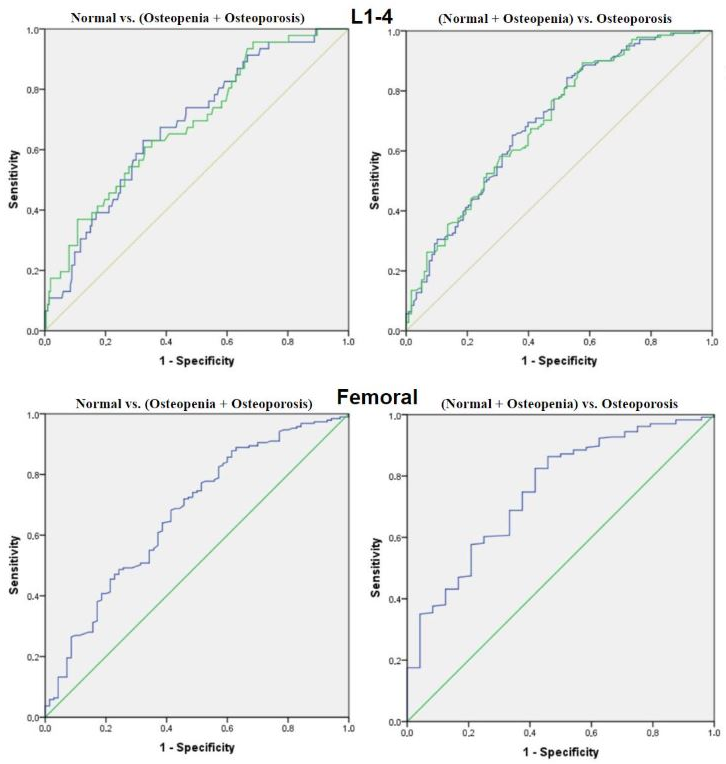

3.5. Diagnostic Performance of CT-Derived HU Values

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Starzl, T.E.; Groth, C.G.; Brettschneider, L.; Penn, I.; Fulginiti, V.A.; Moon, J.B.; Blanchard, H.; Martin, A.J., Jr.; Porter, K.A. Orthotopic homotransplantation of the human liver. Ann. Surg. 1968, 168, 392–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åberg, F. Quality of life after liver transplantation. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2020, 46–47, 101684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbulut, S.; Yilmaz, S. Liver transplantation in Turkey: Historical review and future perspectives. Transplant. Rev. 2015, 29, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastasilakis, A.D.; Tsourdi, E.; Makras, P.; Polyzos, S.A.; Meier, C.; McCloskey, E.V.; Pepe, J.; Zillikens, M.C. Bone disease following solid organ transplantation: A narrative review and recommendations for management from The European Calcified Tissue Society. Bone 2019, 127, 401–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbulut, S.; Ozer, A.; Saritas, H.; Yilmaz, S. Factors affecting anxiety, depression, and self-care ability in patients who have undergone liver transplantation. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 6967–6984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dag, N.; Ozturk, M.; Sigirci, A.; Yilmaz, S. Scoliosis After Liver Transplantation in Pediatric Patients. Eur. J. Ther. 2022, 28, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.H.; Ng, C.H.; Ow, Z.G.W.; Ho, O.T.W.; Tay, P.W.L.; Wong, K.L.; Tan, E.X.X.; Tang, S.Y.; Teo, C.M.; Muthiah, M.D. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the incidence of osteoporosis and fractures after liver transplant. Transpl. Int. 2021, 34, 1032–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Aguilar, E.F.; Pérez-Escobar, J.; Sánchez Herrera, D.; García-Alanis, M.; Toapanta-Yanchapaxi, L.; Gonzalez-Flores, E.; García-Juárez, I. Bone Disease and Liver Transplantation: A Review. Transplant. Proc. 2021, 53, 2346–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, J.E. Osteoporosis in liver diseases and after liver transplantation. J. Hepatol. 2003, 38, 856–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnool, S.; Shah, N.; Ekanayake, P. Treatment of osteoporosis in the solid organ transplant recipient: An organ-based approach. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, 16, 20420188251347351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handzlik-Orlik, G.; Holecki, M.; Wilczyński, K.; Duława, J. Osteoporosis in liver disease: Pathogenesis and management. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 7, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravaioli, F.; Pivetti, A.; Di Marco, L.; Chrysanthi, C.; Frassanito, G.; Pambianco, M.; Sicuro, C.; Gualandi, N.; Guasconi, T.; Pecchini, M.; et al. Role of Vitamin D in Liver Disease and Complications of Advanced Chronic Liver Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, E.G.; Vega, M.V.; Rivas, A.M.; Meek, S.; Yang, L.; Ball, C.T.; Kearns, A.E. Evaluation of Factors Associated with Fracture and Loss of Bone Mineral Density Within 1 Year After Liver Transplantation. Endocr. Pr. 2021, 27, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarici, K.B.; Akbulut, S.; Uremis, M.M.; Garzali, I.U.; Kucukakcali, Z.; Koc, C.; Turkoz, Y.; Usta, S.; Baskiran, A.; Aloun, A.; et al. Evaluation of Bone Mineral Metabolism After Liver Transplantation by Bone Mineral Densitometry and Biochemical Markers. Transplant. Proc. 2023, 55, 1239–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuhart, C.R.; Yeap, S.S.; Anderson, P.A.; Jankowski, L.G.; Lewiecki, E.M.; Morse, L.R.; Rosen, H.N.; Weber, D.R.; Zemel, B.S.; Shepherd, J.A. Executive Summary of the 2019 ISCD Position Development Conference on Monitoring Treatment, DXA Cross-calibration and Least Significant Change, Spinal Cord Injury, Peri-prosthetic and Orthopedic Bone Health, Transgender Medicine, and Pediatrics. J. Clin. Densitom. 2019, 22, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slart, R.; Punda, M.; Ali, D.S.; Bazzocchi, A.; Bock, O.; Camacho, P.; Carey, J.J.; Colquhoun, A.; Compston, J.; Engelke, K.; et al. Updated practice guideline for dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2025, 52, 539–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dag, N.; Karatoprak, S.; Ozturk, M.; Karatoprak, N.B.; Sigirci, A.; Yilmaz, S. Investigation of the prognostic value of psoas muscle area measurement in pediatric patients before liver transplantation: A single-center retrospective study. Clin. Transplant. 2021, 35, e14416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, M.; Dag, N.; Sigirci, A.; Yilmaz, S. Evaluation of Early and Late Complications of Pediatric Liver Transplantation with Multi-slice Computed Tomography: A High-Volume Transplant Single-Center Study. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 32, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Crawford, C.H., 3rd; Glassman, S.D.; Dimar, J.R., 2nd; Gum, J.L.; Carreon, L.Y. Correlation between bone density measurements on CT or MRI versus DEXA scan: A systematic review. N. Am. Spine Soc. J. 2023, 14, 100204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, N.; Hadi, M.S.; Lillard, J.C.; Passias, P.G.; Linzey, J.R.; Saadeh, Y.S.; LaBagnara, M.; Park, P. Alternatives to DEXA for the assessment of bone density: A systematic review of the literature and future recommendations. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2023, 38, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, I.; Nunes, C.; Pereira, F.; Travassos, R.; Ribeiro, M.P.; Marques, F.; McEvoy, M.; Santos, M.; Oliveira, C.; Marto, C.M.; et al. Bone Mineral Density through DEXA and CBCT: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, E.G.; McKenna, A.; Yang, L.; Ball, C.T.; Kearns, A.E. Five-year evaluation of bone health in liver transplant patients: Developing a risk score for predicting bone fragility progression beyond the first year. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1467825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and elaboration. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12, 1500–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Voogd, F.; van Wassenaer, E.A.; Mookhoek, A.; Bots, S.; van Gennep, S.; Löwenberg, M.; D’Haens, G.R.; Gecse, K.B. Intestinal Ultrasound Is Accurate to Determine Endoscopic Response and Remission in Patients with Moderate to Severe Ulcerative Colitis: A Longitudinal Prospective Cohort Study. Gastroenterology 2022, 163, 1569–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.; Foldes, A.J.; Hiller, N.; Simanovsky, N.; Szalat, A. Opportunistic screening for osteoporosis and osteopenia by routine computed tomography scan: A heterogeneous, multiethnic, middle-eastern population validation study. Eur. J. Radiol. 2021, 136, 109568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirayesh Islamian, J.; Garoosi, I.; Abdollahi Fard, K.; Abdollahi, M.R. Comparison between the MDCT and the DXA scanners in the evaluation of BMD in the lumbar spine densitometry. Egypt. J. Radiol. Nucl. Med. 2016, 47, 961–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Choi, M.K.; Kim, S.M.; Lim, J.K. Diagnostic efficacy of Hounsfield units in spine CT for the assessment of real bone mineral density of degenerative spine: Correlation study between T-scores determined by DEXA scan and Hounsfield units from CT. Acta Neurochir. 2016, 158, 1421–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyz, M.; Kapinas, A.; Holton, J.; Pyzik, R.; Boszczyk, B.M.; Quraishi, N.A. The computed tomography-based fractal analysis of trabecular bone structure may help in detecting decreased quality of bone before urgent spinal procedures. Spine J. 2017, 17, 1156–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löffler, M.T.; Jacob, A.; Scharr, A.; Sollmann, N.; Burian, E.; El Husseini, M.; Sekuboyina, A.; Tetteh, G.; Zimmer, C.; Gempt, J.; et al. Automatic opportunistic osteoporosis screening in routine CT: Improved prediction of patients with prevalent vertebral fractures compared to DXA. Eur. Radiol. 2021, 31, 6069–6077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löffler, M.T.; Jacob, A.; Valentinitsch, A.; Rienmüller, A.; Zimmer, C.; Ryang, Y.M.; Baum, T.; Kirschke, J.S. Improved prediction of incident vertebral fractures using opportunistic QCT compared to DXA. Eur. Radiol. 2019, 29, 4980–4989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, E.M.; Neves, J.R.; Teixeira, A.; Frada, R.; Atilano, P.; Oliveira, F.; Veigas, T.; Miranda, A. Efficacy of Hounsfield Units Measured by Lumbar Computer Tomography on Bone Density Assessment: A Systematic Review. Spine 2022, 47, 702–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.E.; Park, J.H.; Kim, K.A.; Choi, H.S. Discordance in Bone Mineral Density between the Lumbar Spine and Femoral Neck Is Associated with Renal Dysfunction. Yonsei Med. J. 2022, 63, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crilly, R.G.; Cox, L. A comparison of bone density and bone morphology between patients presenting with hip fractures, spinal fractures or a combination of the two. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2013, 14, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Categories | n (%) | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 259 | 55.68 ± 14.40 | |

| Age groups | <60 | 134 (51.7) | |

| ≥60 | 125 (48.3) | ||

| Sex | Male | 163 (62.9) | |

| Female | 96 (37.1) | ||

| Lumbar spine BMD (g/cm2) | 259 | 0.80 ± 0.13 | |

| Lumbar spine T-score | 259 | −2.37 ± 1.45 | |

| Lumbar T-score category | Normal | 46 (17.8) | |

| Osteopenia | 95 (36.7) | ||

| Osteoporosis | 118 (45.5) | ||

| Femoral BMD (g/cm2) | 259 | 0.85 ± 0.18 | |

| Femoral T-score | 259 | −0.74 ± 1.24 | |

| Femoral T-score category | Normal | 186 (71.8) | |

| Osteopenia | 46 (17.8) | ||

| Osteoporosis | 27 (10.4) | 55.68 ± 14.40 |

| Variables | <60 Years (n = 134) | ≥60 Years (n = 125) | Mean Difference (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sagittal mean HU | 207 ± 52.5 | 164 ± 44.8 | 43.6 (31.6–55.6) | <0.001 |

| Axial mean HU | 208 ± 80.5 | 162 ± 44.5 | 45.9 (29.8–62.0) | <0.001 |

| Femoral HU | 313 ± 69.2 | 277 ± 68.8 | 36.7 (19.8–53.6) | <0.001 |

| Lumbar BMD (g/cm2) | 0.84 ± 0.13 | 0.76 ± 0.14 | 0.08 (−0.05–0.21) | 0.208 |

| Lumbar T-score | −2.29 ± 1.62 | −2.46 ± 1.24 | 0.17 (−0.19–0.52) | 0.355 |

| Femoral BMD (g/cm2) | 0.85 ± 0.18 | 0.85 ± 0.17 | 0.00 (−0.04–0.05) | 0.884 |

| Femoral T-score | −0.70 ± 1.32 | −0.78 ± 1.16 | 0.08 (−0.23–0.38) | 0.618 |

| Parameters | Groups | Mean ± SD | 95%CI for Mean | p | Post Hoc | p | Mean Difference (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sagittal HU | Normal (n = 46) | 216 ± 54.3 | 200–233 | <0.001 | 0 vs. 1 | 0.080 | 19.3 (−1.8–40.3) |

| Osteopenia (n = 95) | 197± 45.1 | 188–206 | 0 vs. 2 | <0.001 | 51.3 (30.9–71.6) | ||

| Osteoporosis (n = 118) | 165 ± 51.3 | 156–175 | 1 vs. 2 | <0.001 | 32.0 (15.8–48.13) | ||

| Axial HU | Normal (n = 46) | 214 ± 55.5 | 197–230 | <0.001 | 0 vs. 1 | 0.453 | 14.3 (−13.8–42.5) |

| Osteopenia (n = 95) | 200 ± 86.3 | 182–217 | 0 vs. 2 | <0.001 | 51.9 (23.7–78.1) | ||

| Osteoporosis (n = 118) | 163 ± 49.7 | 154–172 | 1 vs. 2 | <0.001 | 36.6 (15.0–58.2) | ||

| Femoral HU | Normal (n = 186) | 307 ± 69.7 | 297–317 | <0.001 | 0 vs. 1 | 0.040 | 27.6 (0.96–54.2) |

| Osteopenia (n = 46) | 279 ± 68.9 | 259–300 | 0 vs. 2 | <0.001 | 68.3 (33.2–103.3) | ||

| Osteoporosis (n = 24) | 239 ± 58.5 | 214–263 | 1 vs. 2 | 0.051 | 40.7 (−0.09–81.4) |

| Groups | Parameters | AUC (95% CI) | p | Cutt-Off (HU) | Sens | Spec | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal vs. (Osteopeni + Osteoporosis) | Sagittal mean HU (L1–L4) | 0.68 (0.60–0.76) | <0.001 | 203 | 0.63 | 0.68 | 0.29 | 0.89 |

| Axial mean HU (L1–L4) | 0.69 (0.60–0.77) | <0.001 | 205 | 0.63 | 0.70 | 0.28 | 0.89 | |

| Femoral HU | 0.67 (0.60–0.75) | <0.001 | 240 | 0.83 | 0.57 | 0.79 | 0.63 | |

| (Normal + Osteopenia) vs. Osteoporosis | Sagittal mean HU (L1–L4) | 0.70 (0.64–0.76) | <0.001 | 198 | 0.64 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.63 |

| Axial mean HU (L1–L4) | 0.70 (0.64–0.76) | <0.001 | 200 | 0.62 | 0.66 | 0.67 | 0.61 | |

| Femoral HU | 0.75 (0.65–0.85) | <0.001 | 237 | 0.82 | 0.63 | 0.81 | 0.65 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dag, N.; Ulubaba, H.E.; Tasolar, S.; Candur, M.; Akbulut, S. Opportunistic Bone Health Assessment Using Contrast-Enhanced Abdominal CT: A DXA-Referenced Analysis in Liver Transplant Recipients. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010029

Dag N, Ulubaba HE, Tasolar S, Candur M, Akbulut S. Opportunistic Bone Health Assessment Using Contrast-Enhanced Abdominal CT: A DXA-Referenced Analysis in Liver Transplant Recipients. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010029

Chicago/Turabian StyleDag, Nurullah, Hilal Er Ulubaba, Sevgi Tasolar, Mehmet Candur, and Sami Akbulut. 2026. "Opportunistic Bone Health Assessment Using Contrast-Enhanced Abdominal CT: A DXA-Referenced Analysis in Liver Transplant Recipients" Diagnostics 16, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010029

APA StyleDag, N., Ulubaba, H. E., Tasolar, S., Candur, M., & Akbulut, S. (2026). Opportunistic Bone Health Assessment Using Contrast-Enhanced Abdominal CT: A DXA-Referenced Analysis in Liver Transplant Recipients. Diagnostics, 16(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010029