Whole Spine and Sacroiliac Joint MRI of Patients With and Without Metabolic Syndrome: A Preliminary Study

Abstract

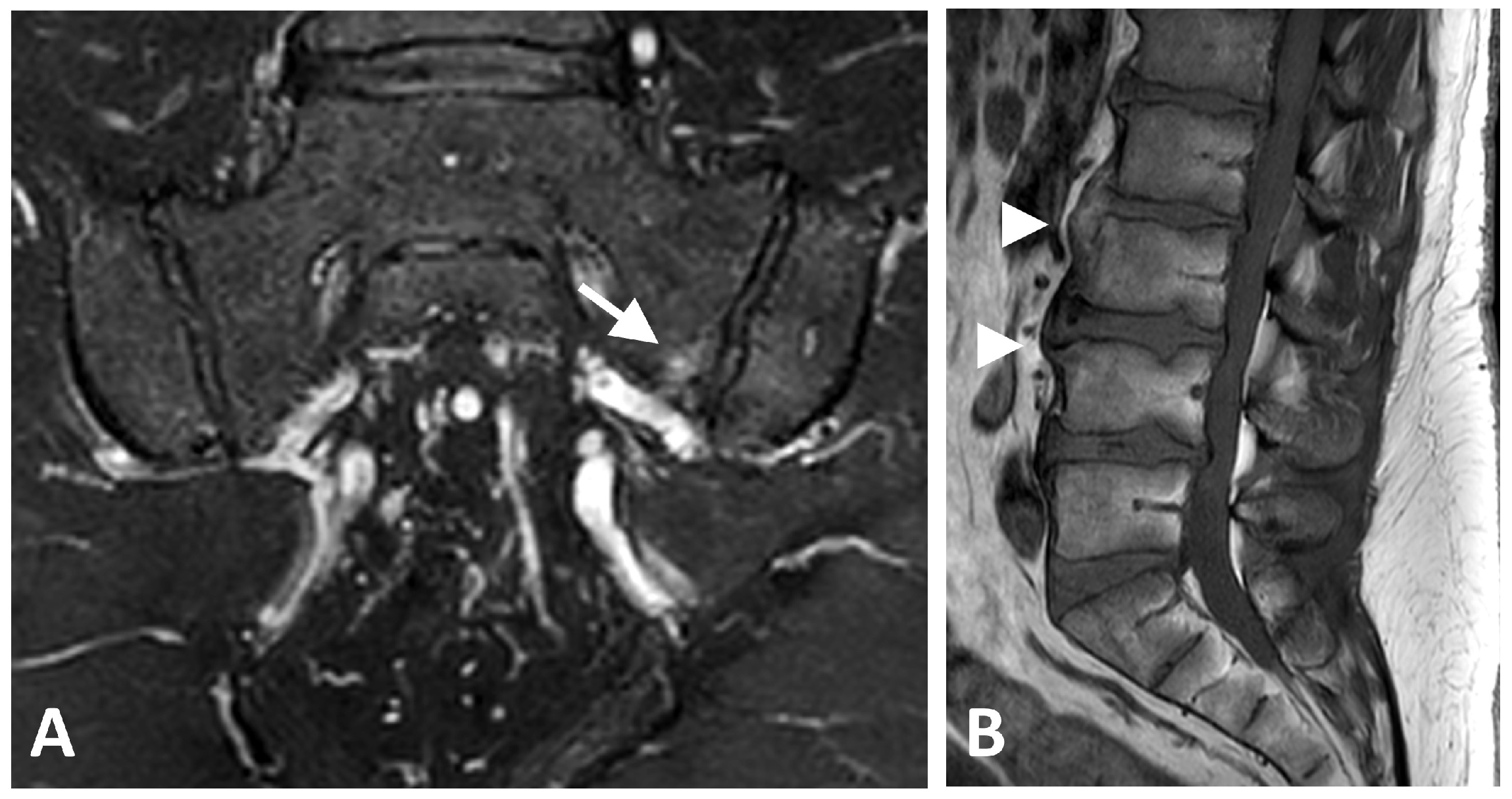

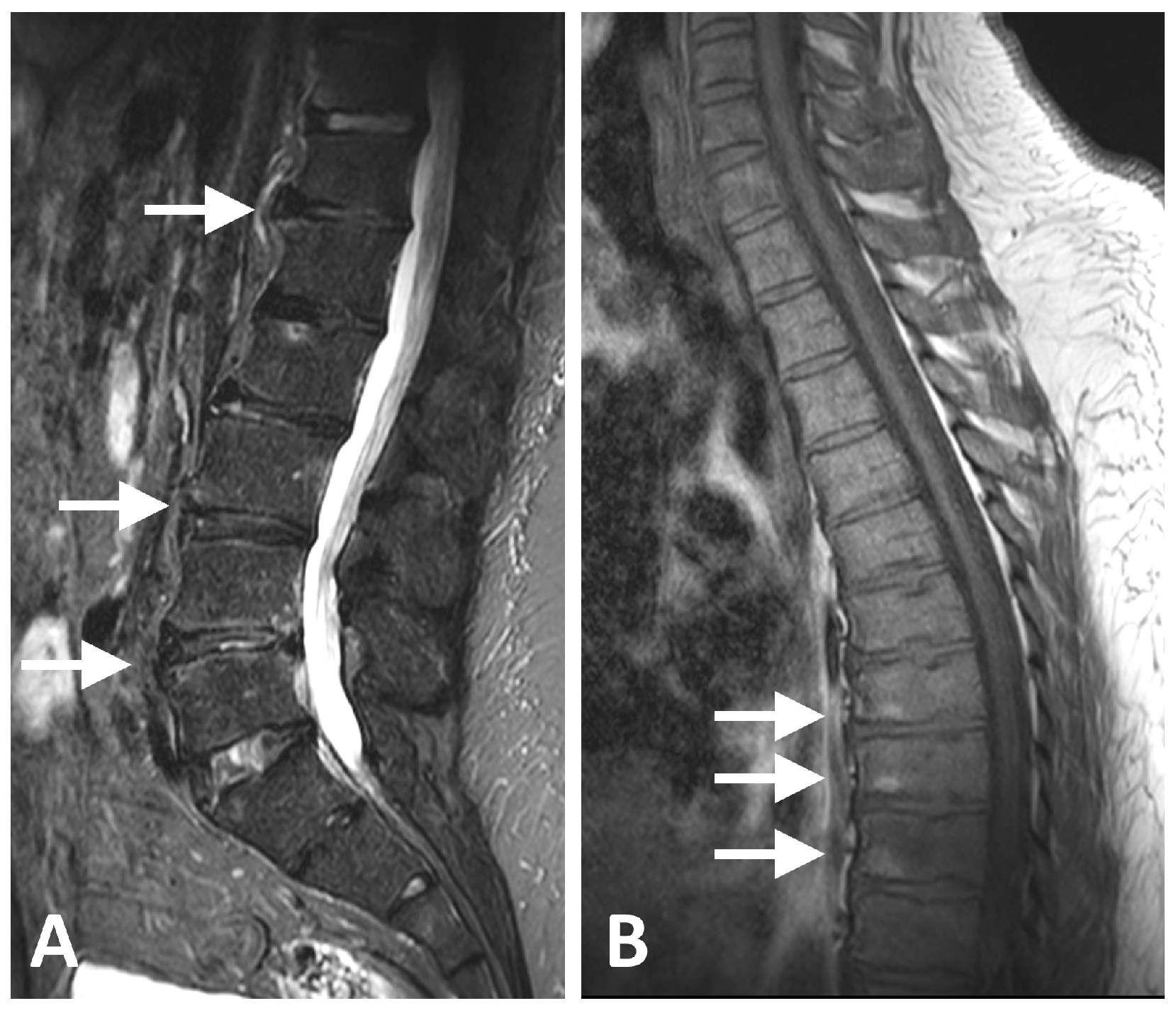

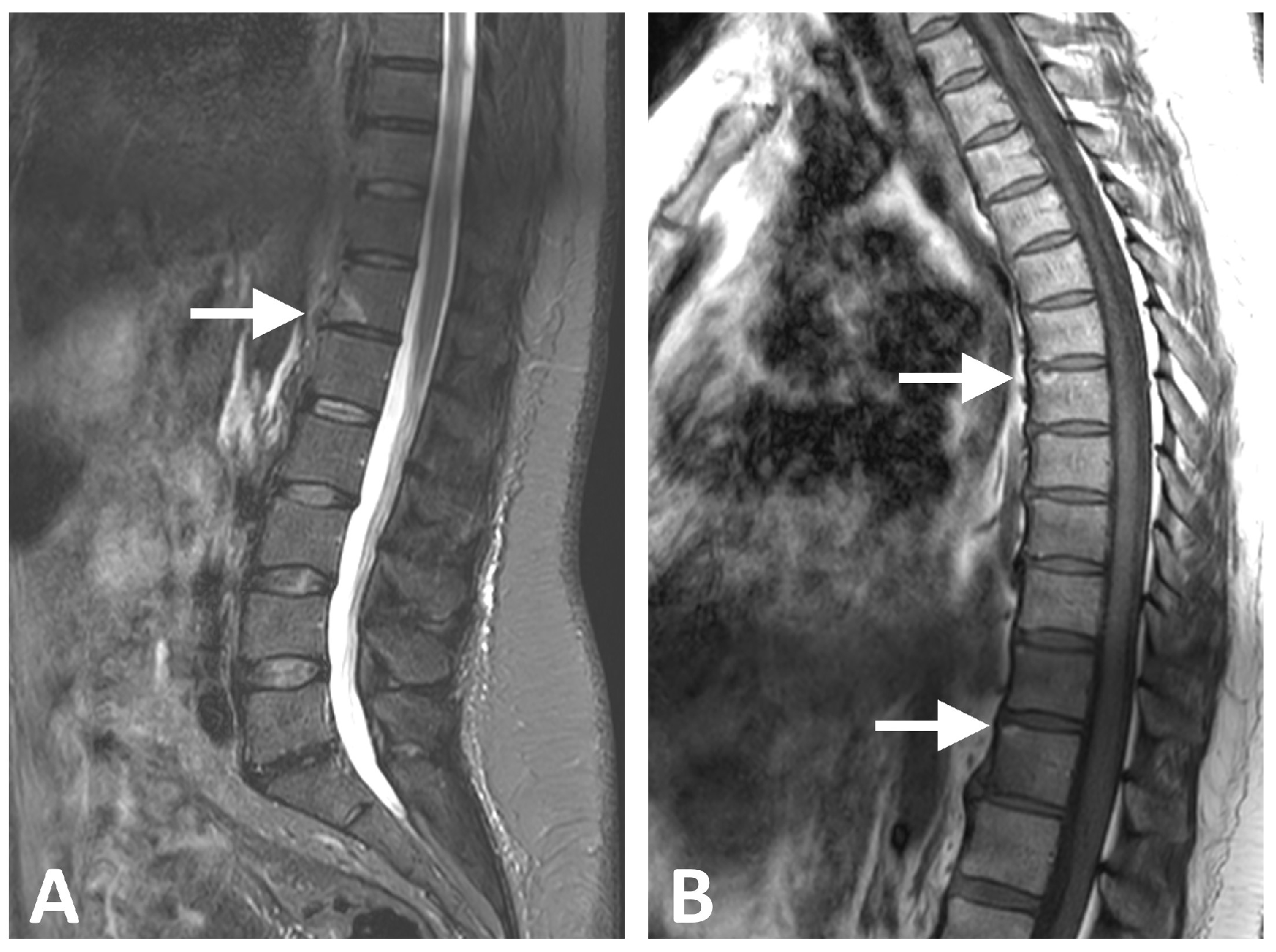

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Population

2.2. MRI Scans and Evaluation

2.3. Scoring Description

- •

- BME, fat lesion, erosion, and sclerosis:

- ◦

- One point each for the following regions (eight regions in total): anterior and posterior, lower and upper parts, for both ilium and sacrum.

- ◦

- Total for these changes: 8 points each (32 points in total).

- •

- Ankylosis:

- ◦

- One point each for the same eight regions (anterior/posterior, lower/upper, ilium/sacrum) plus two points for anterior bridges.

- ◦

- Total for ankylosis: 10 points.

- •

- Enthesitis and Capsulitis:

- ◦

- Two points for each side (right and left).

- ◦

- Total for enthesitis and capsulitis: 4 points.

- •

- For each vertebral unit (two adjacent vertebrae around the disk space), score 0–2 points for BME, fat lesion, erosion, posterior elements inflammation, and syndesmophytes.

- •

- Twenty-three vertebral units, scored for vertebral body and posterior elements.

2.4. Ethics

3. Results

MRI Scores

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALT | Alanine Aminotransferase |

| AST | Aspartate Aminotransferase |

| AS | Ankylosing Spondylitis |

| axSpA | Axial Spondyloarthritis |

| BME | Bone Marrow Edema |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| DM | Diabetes Mellitus |

| DISH | Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram (if not used, remove) |

| ESR | Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate |

| GLP-1 RA | Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist |

| HbA1c | Hemoglobin A1c |

| HTN | Hypertension |

| ICH–GCP | International Conference on Harmonization–Good Clinical Practice |

| IFG | Impaired Fasting Glucose |

| IL | Interleukin (if IL-6 or IL-1 mentioned elsewhere) |

| IHD | Ischemic Heart Disease |

| MRS | Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MeS | Metabolic Syndrome |

| MSK | Musculoskeletal |

| NCEP ATP III | National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III |

| OSA | Obstructive Sleep Apnea |

| SIJ/SIJs | Sacroiliac Joint/Sacroiliac Joints |

| T1-W | T1-Weighted |

| T2-W | T2-Weighted |

| UA | Uric Acid |

References

- Resnick, D.; Niwayama, G. Radiographic and Pathologic Features of Spinal Involvement in Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis (DISH). Radiology 1976, 119, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mader, R.; Verlaan, J.J.; Buskila, D. Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis: Clinical Features and Pathogenic Mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2013, 9, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, E.; Ishihara, S.; Azuma, K.; Michikawa, T.; Suzuki, S.; Tsuji, O.; Nori, S.; Nagoshi, N.; Yagi, M.; Takayama, M.; et al. Metabolic Syndrome Is a Predisposing Factor for Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis. Neurospine 2021, 18, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coaccioli, S.; Fatati, G.; Di Cato, L.; Marioli, D.; Patucchi, E.; Pizzuti, C.; Ponteggia, M.; Puxeddu, A. Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis in Diabetes Mellitus, Impaired Glucose Tolerance and Obesity. Panminerva Medica 2000, 42, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brikman, S.; Mader, R.; Bieber, A. High Frequency of Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis in Patients with Obesity Hypoventilation Syndrome. J. Rheumatol. 2024, 51, 733–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brikman, S.; Lubani, Y.; Mader, R.; Bieber, A. High Prevalence of Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis (DISH) among Obese Young Patients—A Retrospective Observational Study. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2024, 65, 152356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaily, N.; Roshkovan, L.; Bieber, A.; Mader, R.; Brikman, S. The Presence of Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis (DISH) among Patients with High Burden of Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Retrospective Study. Int. J. Rheumatol. 2024, 2024, 8877237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarzi-Puttini, P.; Atzeni, F. New Developments in Our Understanding of DISH (Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis). Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2004, 16, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuperus, J.S.; Oudkerk, S.F.; Foppen, W.; Hoesein, F.A.M.; Gielis, W.P.; Waalwijk, J.; Regan, E.A.; Lynch, D.A.; Oner, F.C.; De Jong, P.A.; et al. Criteria for Early-Phase Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis: Development and Validation. Radiology 2019, 291, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaniv, G.; Bader, S.; Lidar, M.; Herman, A.; Shazar, N.; Aharoni, D.; Eshed, I. The Natural Course of Bridging Osteophyte Formation in Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis: Retrospective Analysis of Consecutive CT Examinations over 10 Years. Rheumatology 2014, 53, 1951–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieber, A.; Masala, I.F.; Mader, R.; Atzeni, F. Differences Between Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis and Spondyloarthritis. Immunotherapy 2020, 12, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mader, R.; Pappone, N.; Baraliakos, X.; Eshed, I.; Sarzi-Puttini, P.; Atzeni, F.; Bieber, A.; Novofastovski, I.; Kiefer, D.; Verlaan, J.-J.; et al. Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis (DISH) and a Possible Inflammatory Component. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2021, 23, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arad, U.; Elkayam, O.; Eshed, I. Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis: Similarities to Axial Spondyloarthritis. Clin. Rheumatol. 2017, 36, 1545–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badr, S.; Cotten, A.; Lombardo, D.; Ruschke, S.; Karampinos, D.C.; Ramdane, N.; Genin, M.; Paccou, J. Bone Marrow Adiposity Alterations in Postmenopausal Women with Type 2 Diabetes Are Site-Specific. J. Endocr. Soc. 2024, 8, bvae161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, G.N.; Ewing, S.K.; Schafer, A.L.; Gudnason, V.; Sigurdsson, S.; Lang, T.; Hue, T.F.; Kado, D.M.; Vittinghoff, E.; Rosen, C.; et al. Saturated and Unsaturated Bone Marrow Lipids Have Distinct Effects on Bone Density and Fracture Risk in Older Adults. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2022, 37, 700–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falsetti, P.; Conticini, E.; Baldi, C.; Bardelli, M.; Cantarini, L.; Frediani, B. Diffuse Peripheral Enthesitis in Metabolic Syndrome: A Retrospective Clinical and Power Doppler Ultrasound Study. Reum. Clin. 2022, 18, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, S.M.; Brewer, H.B.; Cleeman, J.I.; Smith, S.C.; Lenfant, C. Definition of Metabolic Syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association Conference on Scientific Issues Related to Definition. Circulation 2004, 109, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, I.H.; Hermann, K.G.; Haibel, H.; Althoff, C.E.; Listing, J.; Burmester, G.R.; Krause, A.; Bohl-Bühler, M.; Freundlich, B.; Rudwaleit, M.; et al. Effects of Etanercept Versus Sulfasalazine in Early Axial Spondyloarthritis on Active Inflammatory Lesions as Detected by Whole-Body MRI (ESTHER): A 48-Week Randomised Controlled Trial. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011, 70, 590–596, Correction in Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011, 70, 1350. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2010.139667corr1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, B.G.; Bachmann, L.M.; Pfirrmann, C.W.A.; Kissling, R.O.; Zubler, V. Whole Body Magnetic Resonance Imaging Features in Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis in Conjunction with Clinical Variables to Whole Body Mri and Clinical Variables in Ankylosing Spondylitis. J. Rheumatol. 2016, 43, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziade, N.; Udod, M.; Kougkas, N.; Tsiami, S.; Baraliakos, X. Significant Overlap of Inflammatory and Degenerative Features on Imaging among Patients with Degenerative Disc Disease, Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis and Axial Spondyloarthritis: A Real-Life Cohort Study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2024, 26, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, Y.; Amati, F.; Schwartz, A.V.; Danielson, M.E.; Li, X.; Boudreau, R.; Cauley, J.A. Vertebral Bone Marrow Fat, Bone Mineral Density and Diabetes: The Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Study. Bone 2017, 97, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, E.W.; Greenblatt, L.; Eajazi, A.; Torriani, M.; Bredella, M.A. Marrow Adipose Tissue Composition in Adults with Morbid Obesity. Bone 2017, 97, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auðunsson, A.B.; Elíasson, G.J.; Steingrímsson, E.; Aspelund, T.; Sigurdsson, S.; Launer, L.; Gudnason, V.; Jonsson, H.; Banno, T.; Togawa, D.; et al. Prevalence of Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis (DISH) of the Whole Spine and Its Association with Lumbar Spondylosis and Knee Osteoarthritis: The ROAD Study. J. Orthop. Sci. 2022, 22, 314–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, D.; Godolias, M.; Sewerin, P.; Kiltz, U.; Tsiami, S.; Andreica, I.; Baraliakos, X. Influence of Obesity on Radiographic Changes in Patients With Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis. J. Rheumatol. 2025, 52, 1028–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latourte, A.; Charlon, S.; Etcheto, A.; Feydy, A.; Allanore, Y.; Dougados, M.; Molto, A. Imaging Findings Suggestive of Axial Spondyloarthritis in Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis. Arthritis Care Res. 2018, 70, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, J.J.H.; Foster-Davies, H.; Salem, A.; Hoole, A.L.; Obaid, D.R.; Halcox, J.P.J.; Stephens, J.W. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists Improve Biomarkers of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2021, 23, 1806–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | All (N = 24) | Metabolic Syndrome (N = 15) | No Syndrome (N = 9) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at imaging, years, mean ± SD (range) | 44.9 ± 3.1 (40–49) | 45.4 ± 3.2 (40–49) | 43.7 ± 3.1 (40–49) | 0.21 |

| Male, n (%) | 12 (50.0) | 9 (60.0) | 3 (33.3) | 0.40 |

| IFG, n (%) | 9 (37.5) | 9 (60.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.007 |

| Large waist circumference, n (%) | 14 (58.3) | 14 (93.3) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| BMI, mean ± SD (range) | 30.3 ± 7.8 (18.7–48.4) | 34.9 ± 6.3 (21.8–48.4) | 22.7 ± 1.6 (18.7–24.0) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 5 (20.8) | 5 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.12 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL, mean ± SD (range) | 170.6 ± 172.3 (43–806) | 223.5 ± 200.2 (58–806) | 82.6 ± 35.7 (43–151) | 0.003 |

| HDL, mg/dL, mean ± SD (range) | 50.2 ± 10.4 (32–73) | 45.3 ± 6.5 (32–59) | 58.3 ± 10.9 (41–73) | 0.007 |

| Type 2 diabetes, n (%) | 3 (12.5) | 3 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.27 |

| IHD, n (%) | 7/23 (30.4) | 7/14 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.019 |

| Laboratory Parameter | All (N = 24) | Metabolic Syndrome (N = 15) | No Syndrome (N = 9) | Test Statistic | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin, µU/mL, mean ± SD (range) | 14.45 ± 18.02 (0.1–196) | 18.90 ± 24.40 (3.4–196) | 6.30 ± 7.43 (0.1–24.0) | 2.80 | 0.004 |

| HbA1c, %, mean ± SD (range) | 5.4 ± 0.5 (4.3–8.8) | 5.4 ± 0.8 (4.8–8.8) | 5.4 ± 0.5 (4.3–5.6) | 0.76 | 0.45 |

| A1C (highest), %, mean ± SD (range) | 5.6 ± 0.7 (4.3–14.8) | 5.7 ± 0.9 (4.8–14.8) | 5.4 ± 0.6 (4.3–5.8) | 2.03 | 0.04 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL, mean ± SD (range) | 0.788 ± 0.204 (0.52–1.36) | 0.807 ± 0.204 (0.55–1.36) | 0.757 ± 0.212 (0.52–1.14) | 0.58 | 0.57 |

| Uric acid, mg/dL, mean ± SD (range) | 5.36 ± 1.37 (2.42–7.20) | 6.04 ± 1.02 (3.58–7.20) | 4.20 ± 1.09 (2.42–5.49) | 3.72 | 0.002 |

| AST, U/L, mean ± SD (range) | 22.0 ± 5.8 (13–35) | 24.0 ± 6.1 (14–35) | 18.8 ± 3.2 (13–23) | 2.36 | 0.028 |

| ALT, U/L, mean ± SD (range) | 23.4 ± 10.3 (9–50) | 27.6 ± 10.1 (10–50) | 16.3 ± 6.2 (9–27) | 3.01 | 0.006 |

| LDL, mg/dL, mean ± SD (range) | 109.6 ± 25.0 (70–170) | 112.4 ± 26.1 (70–170) | 100.4 ± 17.8 (85–141) | 1.18 | 0.25 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL, mean ± SD (range) | 13.5 ± 1.2 (11.3–16.6) | 13.7 ± 1.3 (11.3–16.6) | 13.3 ± 1.0 (12.0–15.1) | 0.82 | 0.42 |

| SIJ | Cervical | Thorax | Lumbar | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRI | All | MeS | No MeS | p | All | MeS | No MeS | p | All | MeS | No MeS | p | All | MeS | No MeS | p |

| Sum of all scores | 0.12 ± 0.33 (0; 0–1) | 0.19 ± 0.39 (0; 0–1) | 0.00 (0; 0–0) | 0.67 | 1.38 ± 3.24 (0; 0–12) | 2.00 ± 3.76 (0; 0–12) | 0.13 ± 0.35 (0; 0–1) | 0.21 | 1.92 ± 3.27 (1; 0–14) | 2.75 ± 3.69 (0; 0–14) | 0.44 ± 0.46 (0; 0–1) | 0.06 | 1.58 ± 2.78 (0; 0–8) | 2.38 ± 3.09 (0; 0–8) | 0.00 (0; 0–0) | 0.034 |

| Total active score | 0.08 ± 0.28 (0; 0–1) | 0.13 ± 0.33 (0; 0–1) | 0.00 (0; 0–0) | 0.64 | 0.38 ± 1.01 (0; 0–4) | 0.50 ± 1.18 (0; 0–1) | 0.13 ± 0.35 (0; 0–1) | 0.66 | 0.25 ± 0.53 (0; 0–2) | 0.31 ± 0.59 (0; 0–2) | 0.11 ± 0.35 (0; 0–1) | 0.53 | 0.25 ± 0.61 (0; 0–2) | 0.38 ± 0.70 (0; 0–2) | 0.00 (0; 0–0) | 0.30 |

| Total Structural score | 0.04 ± 0.20 (0; 0–1) | 0.06 ± 0.24 (0; 0–1) | 0.00 (0; 0–0) | 0.82 | 1.00 ± 2.59 (0; 0–10) | 1.50 ± 3.00 (0; 0–10) | 0.00 (0; 0–0) | 0.19 | 1.67 ± 3.10 (1; 0–14) | 2.44 ± 3.51 (2; 0–14) | 0.33 ± 0.35 (0; 0–2) | 0.04 | 1.33 ± 2.41 (0; 0–8) | 2.00 ± 2.69 (1; 0–8) | 0.00 (0; 0–0) | 0.034 |

| BME | 0.04 ± 0.20 (0; 0–1) | 0.06 ± 0.24 (0; 0–1) | 0.00 (0; 0–0) | 0.82 | 0.38 ± 1.01 (0; 0–4) | 0.50 ± 1.18 (0; 0–4) | 0.13 ± 0.35 (0; 0–1) | 0.70 | 0.25 ± 0.53 (0; 0–1) | 0.31 ± 0.59 (0; 0–2) | 0.11 ± 0.35 (0; 0–1) | 0.53 | 0.25 ± 0.61 (0; 0–2) | 0.38 ± 0.70 (0; 0–2) | 0.00 (0; 0–0) | 0.30 |

| Enthesitis | 0.04 ± 0.20 (0; 0–1) | 0.06 ± 0.24 (0; 0–1) | 0.00 (0; 0–0) | 0.82 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | - |

| Fat lesion | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | - | 0.29 ± 1.23 (0; 0–1) | 0.44 ± 1.46 (0; 0–1) | 0.00 (0; 0–0) | 0.61 | 0.96 ± 1.60 (0.0; 0–6) | 1.44 ± 1.77 (1; 0–6) | 0.22 ± 0.00 (0; 0–2) | 0.06 | 0.38 ± 0.78 (0; 0–3) | 0.56 ± 0.80 (0; 0–3) | 0.00 (0; 0–0) | 0.064 |

| Ankylosis | 0.04 ± 0.20 (0; 0–1) | 0.06 ± 0.24 (0; 0–1) | 0.00 (0; 0–0) | 0.82 | 0.63 ± 2.12 (0; 0–10) | 0.94 ± 2.50 (0; 0–10) | 0.00 (0; 0–0) | 0.44 | 0.67 ± 2.06 (0.0; 0–10) | 0.94 ± 2.42 (0.0; 0–10) | 0.11 ± 0.35 (0; 0–1) | 0.36 | 0.83 ± 1.81 (0; 0–6) | 1.25 ± 2.07 (0; 0–6) | 0.00 (0; 0–0) | 0.11 |

| Erosion | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | - | 0.08 ± 0.41 (0; 0–2) | 0.13 ± 0.49 (0; 0–2) | 0.00 (0; 0–0) | 0.81 | 0.04 ± 0.20 (0; 0–1) | 0.06 ± 0.24 (0; 0–1) | 0.00 (0; 0–0) | 0.81 | 0.13 ± 0.45 (0; 0–2) | 0.19 ± 0.54 (0; 0–2) | 0.00 (0; 0–0) | 0.61 |

| Sclerosis | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | - |

| Capsulitis | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | - | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | - | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | - | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | - |

| MRI | All (N = 24) | Metabolic Syndrome (N = 15) | No Syndrome (N = 9) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRI total sum all | 5.0 ± 7.2 | 7.7 ± 8.0 * | 0.6 ± 0.8 * | 0.013 |

| MRI sum active | 0.96 ± 1.52 | 1.40 ± 1.76 | 0.22 ± 0.44 | 0.08 |

| MRI sum structural | 4.04 ± 6.39 * | 6.27 ± 7.26 * | 0.33 ± 0.71 | 0.014 |

| Bone marrow edema (median; range) | 0.92 ± 1.53 | 1.33 ± 1.80 | 0.22 ± 0.44 | 0.14 |

| Enthesis (median; range) | 0.04 ± 0.20 | 0.07 ± 0.26 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.82 |

| Fat lesion (median; range) | 1.63 ± 2.72 | 2.47 ± 3.13 * | 0.22 ± 0.67 * | 0.013 |

| Ankylosis (median; range) | 2.17 ± 4.78 | 3.40 ± 5.77 | 0.11 ± 0.33 | 0.1 |

| Erosions (median; range) | 0.25 ± 0.68 | 0.40 ± 0.82 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.31 |

| Sclerosis | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | - |

| Capsulitis | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bieber, A.; Brikman, S.; Nujeidat, M.; Novofasovsky, I.; Mader, R.; Eshed, I. Whole Spine and Sacroiliac Joint MRI of Patients With and Without Metabolic Syndrome: A Preliminary Study. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010108

Bieber A, Brikman S, Nujeidat M, Novofasovsky I, Mader R, Eshed I. Whole Spine and Sacroiliac Joint MRI of Patients With and Without Metabolic Syndrome: A Preliminary Study. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(1):108. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010108

Chicago/Turabian StyleBieber, Amir, Shay Brikman, Mohamad Nujeidat, Irina Novofasovsky, Reuven Mader, and Iris Eshed. 2026. "Whole Spine and Sacroiliac Joint MRI of Patients With and Without Metabolic Syndrome: A Preliminary Study" Diagnostics 16, no. 1: 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010108

APA StyleBieber, A., Brikman, S., Nujeidat, M., Novofasovsky, I., Mader, R., & Eshed, I. (2026). Whole Spine and Sacroiliac Joint MRI of Patients With and Without Metabolic Syndrome: A Preliminary Study. Diagnostics, 16(1), 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010108