Calciphylaxis of the Upper Limbs—A Rare and Serious Disease with Multidisciplinary Treatments—A Case Series and Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Case Series

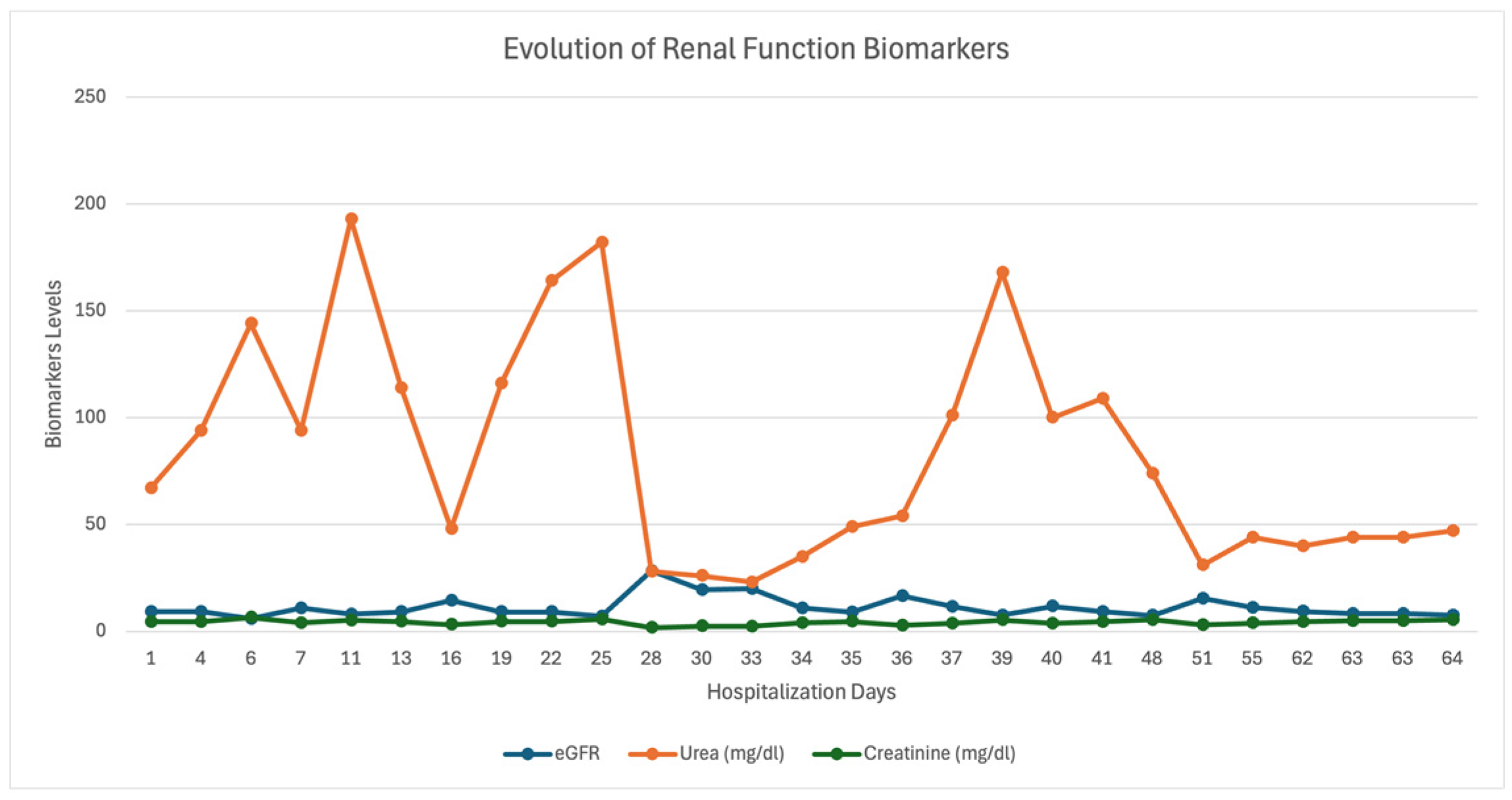

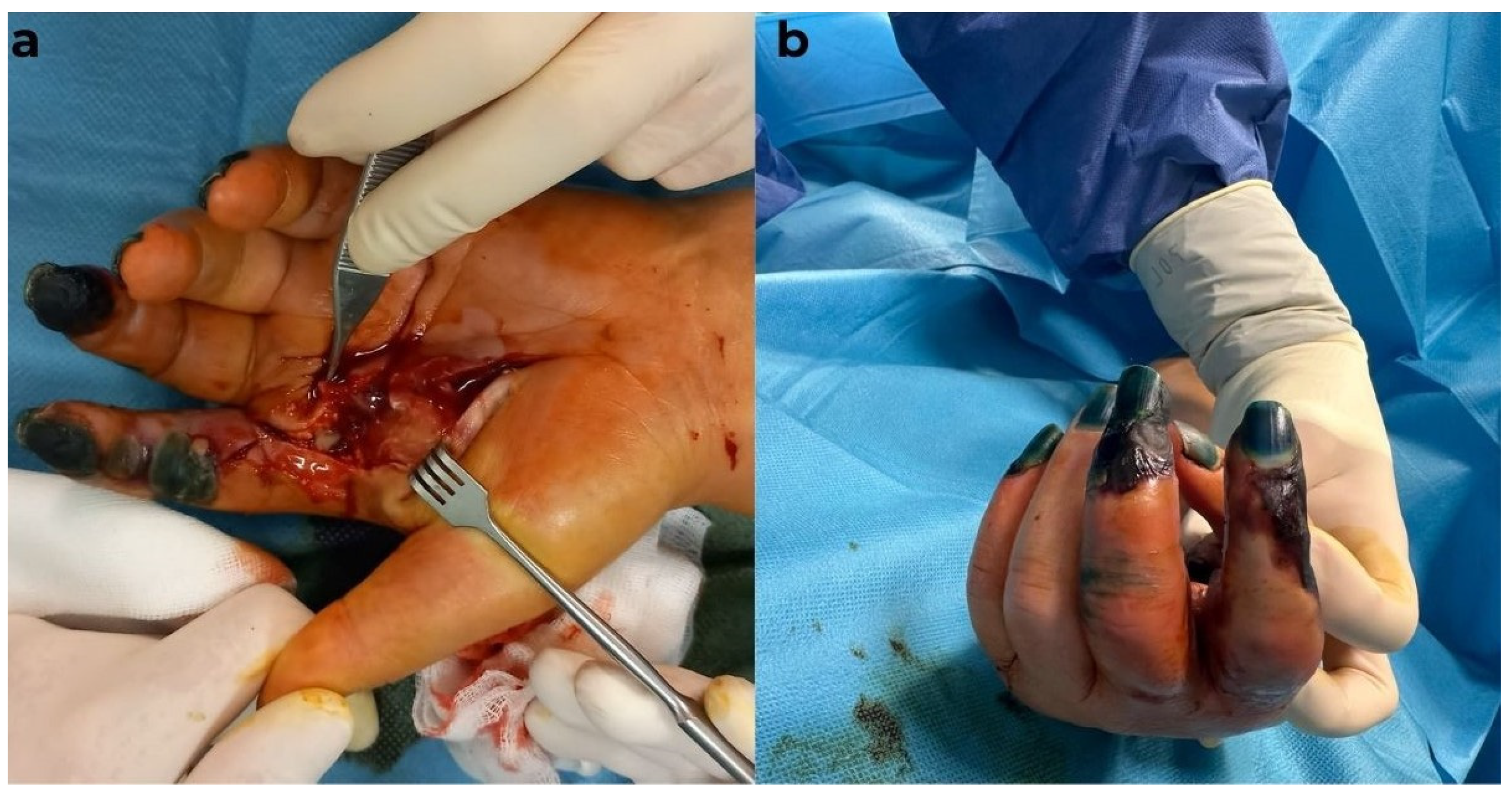

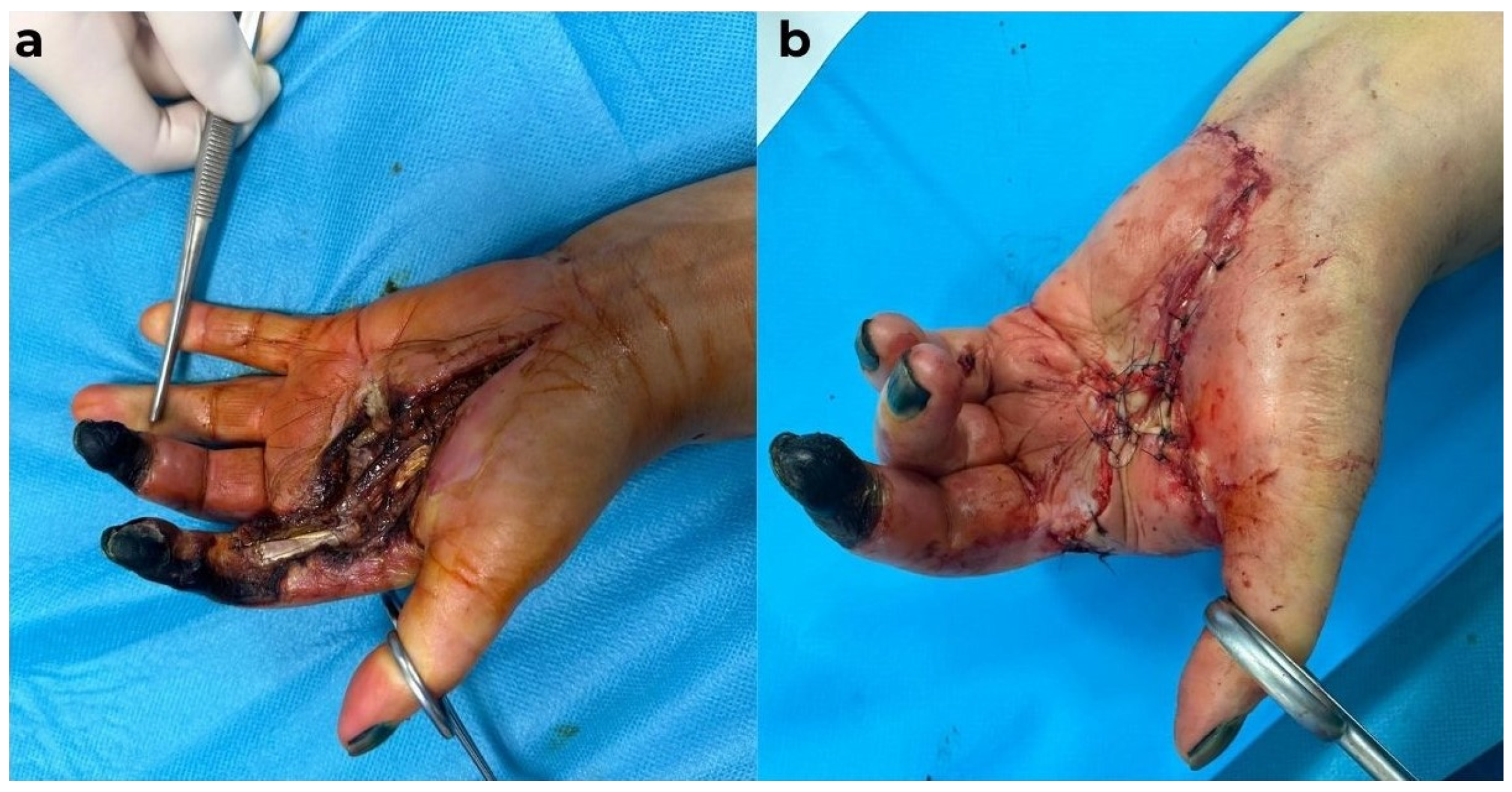

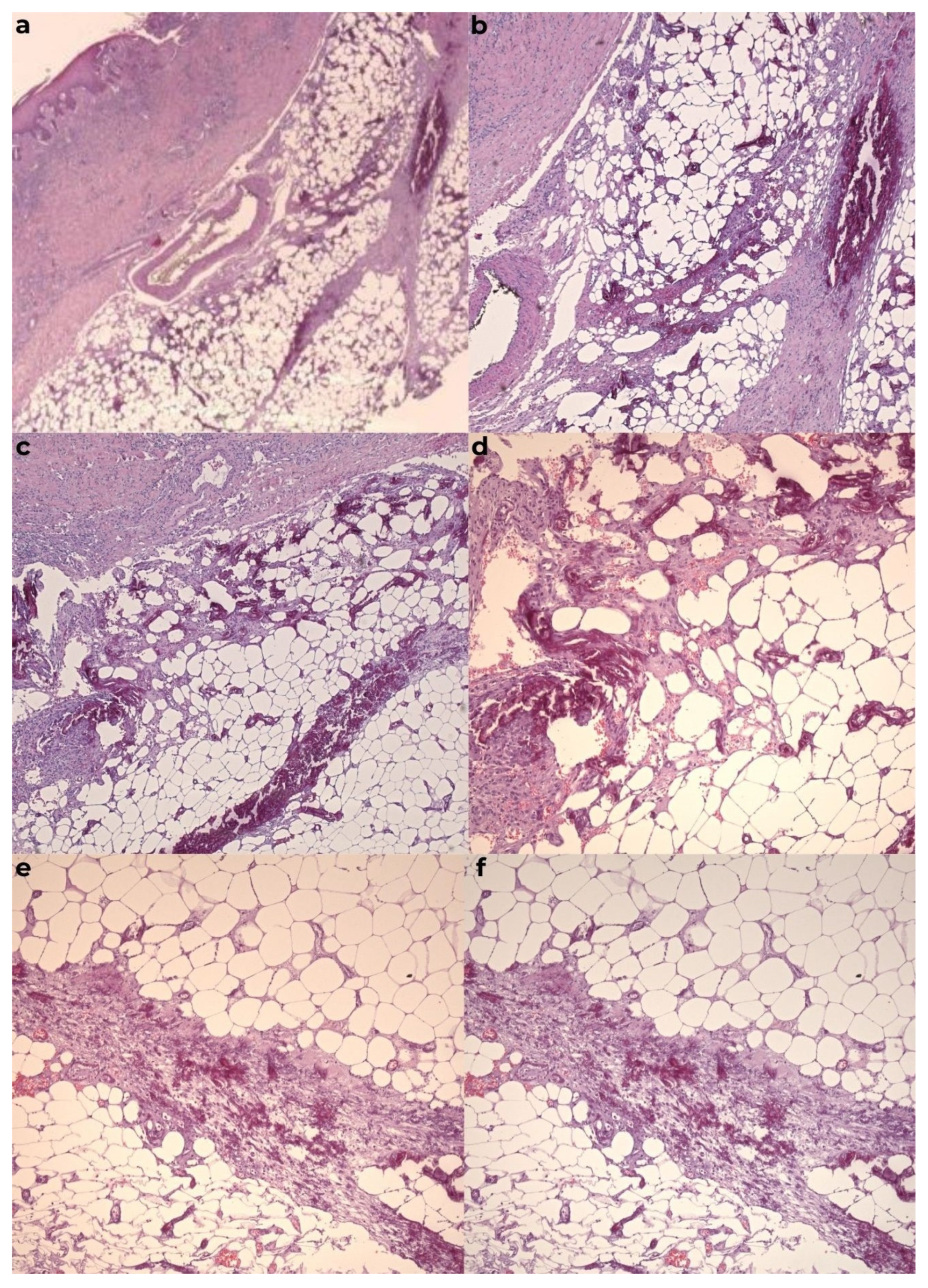

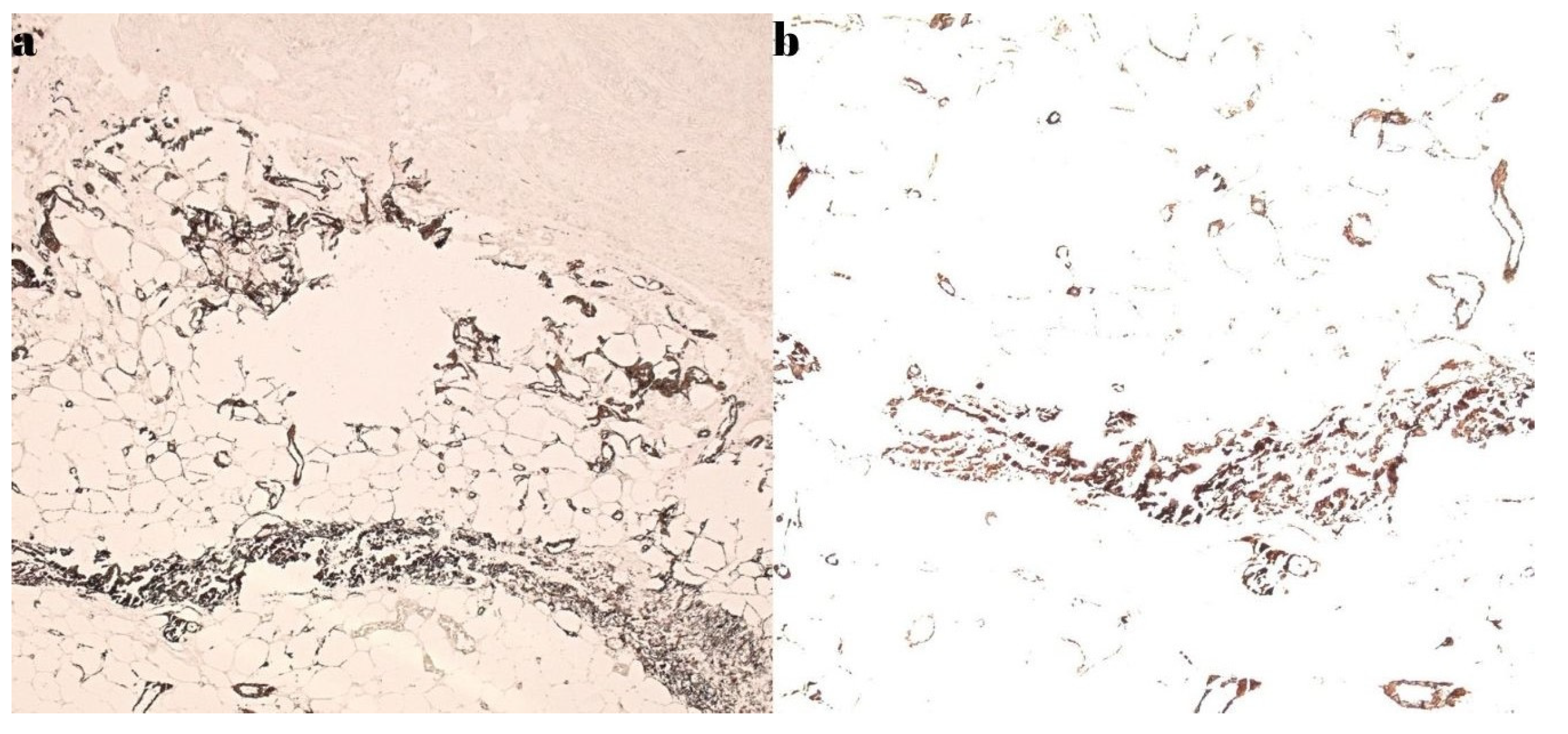

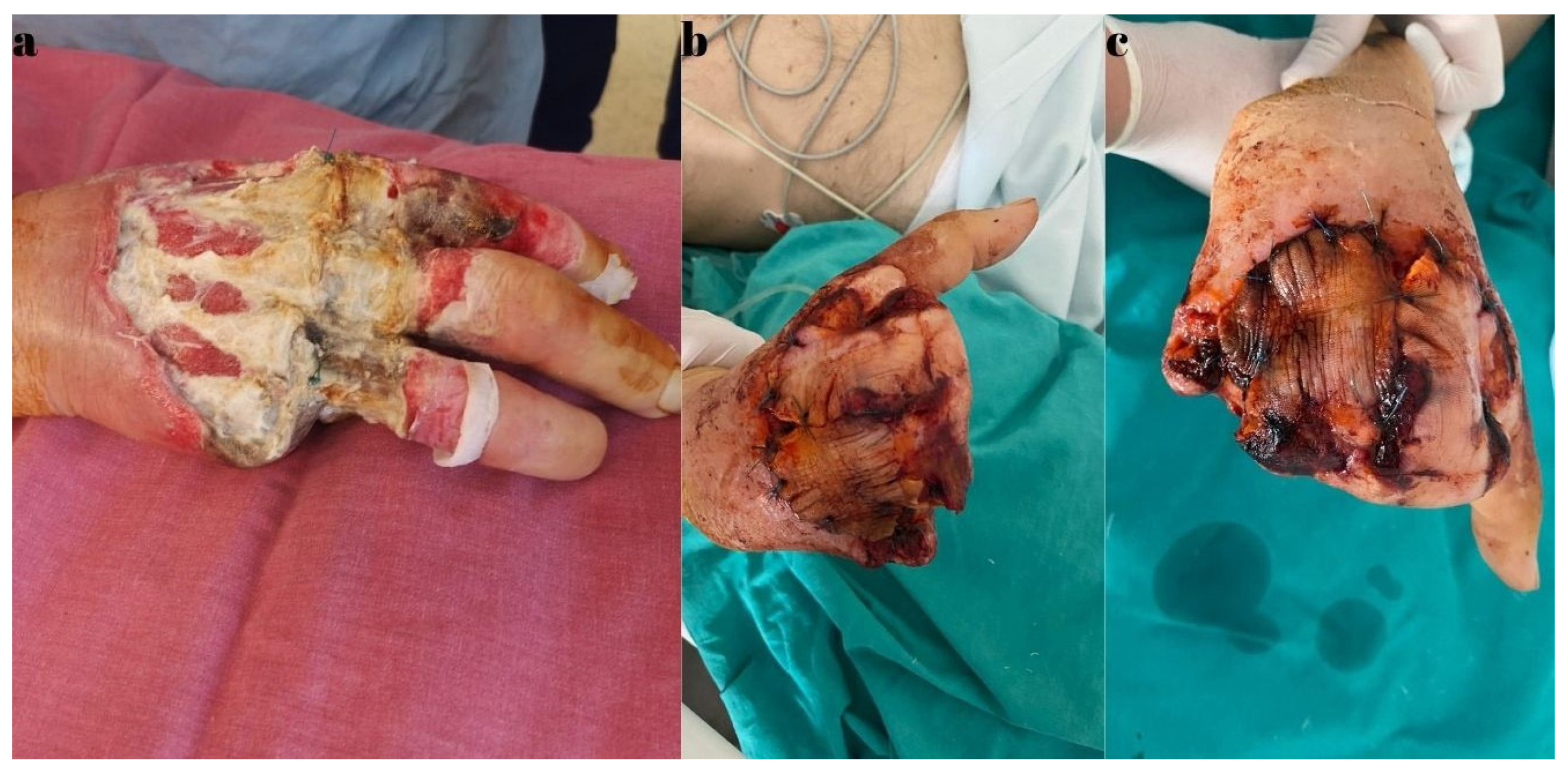

2.1.1. Case Report 1

2.1.2. Case Report 2

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CUA | calcific uremic arteriolopathy |

| CHD | chronic kidney disease |

| ESRD | end-stage renal disease |

| M | male |

| F | female |

| Rx | radiological exam |

| HTN | hypertension |

| D | digit |

| LH | left hand |

| RH | right hand |

| ATS | atherosclerosis |

| DM | diabetes mellitus |

References

- Marques, S.A.; Kakuda, A.C.; Mendaçolli, T.J.; Abbade, L.P.; Marques, M.E. Calciphylaxis: A rare but potentially fatal event of chronic kidney disease. Case report. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2013, 88(6 Suppl. S1), 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roncada, E.V.; Abreu, M.A.; Pereira, M.F.; Oliveira, C.C.; Nai, G.A.; Soares, D.F. Calciphylaxis, a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge: Report of a successful case. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2012, 87, 752–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Róbert, L.; Németh, K.; Marschalkó, M.; Holló, P.; Hidvégi, B. Calcinosis Prevalence in Autoimmune Connective Tissue Diseases-A Retrospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mormile, I.; Mosella, F.; Turco, P.; Napolitano, F.; de Paulis, A.; Rossi, F.W. Calcinosis Cutis and Calciphylaxis in Autoimmune Connective Tissue Diseases. Vaccines 2023, 11, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, T.; Kirkland, G.S.; Dymock, R.B. Cutaneous necrosis from calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1998, 32, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, L.A.; Dickson-Witmer, D.; Witmer, D.R.; Kirby, W. Calciphylaxis mimicking inflammatory breast cancer. Breast J. 2007, 13, 514–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalin, A.S.; Altiparmak, M.R.; Trabulus, S.; Yalin, S.F.; Yalin, G.Y.; Melikoglu, M. Calciphylaxis: A report of six cases and review of literature. Ren. Fail. 2013, 35, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijapati, N.; Fong, S.S.H.; Ansari, O.; Misra, S.; Mercado, E.A.; Myers, M.; Narasimha, V. Calciphylaxis, A Case Series: The Importance of Early Detection. HCA Healthc. J. Med. 2023, 4, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, V.M.; Kramann, R.; Rothe, H.; Kaesler, N.; Korbiel, J.; Specht, P.; Schmitz, S.; Krüger, T.; Floege, J.; Ketteler, M. Calcific uraemic arteriolopathy (calciphylaxis): Data from a large nationwide registry. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2017, 32, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, Y.Z.; Sheetanshu, K.; Lee, X.S.; Christine Chen, Y.C. Calciphylaxis of the fingers: A case report. Asian J. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2022, 17, 34–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielejewska, A.; Bociek, A.; Jaroszyński, A. Calciphylaxis—A fatal complication not only in end-stage renal disease patients. Folia Cardiol. 2020, 15, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigwekar, S.U.; Thadhani, R.; Brandenburg, V.M. Calciphylaxis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1704–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigwekar, S.U.; Zhao, S.; Wenger, J.; Hymes, J.L.; Maddux, F.W.; Thadhani, R.I.; Chan, K.E. A Nationally representative study of calcific uremicarteriolopathy risk factors. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 27, 3421–3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaisne, R.; Péré, M.; Menoyo, V.; Hourmant, M.; Larmet-Burgeot, D. Calciphylaxis epidemiology, risk factors, treatment and survival among French chronic kidney disease patients: A case-control study. BMC Nephrol. 2020, 21, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdalla, A.O.; Al-Khafaji, J.; Taha, M.; Malik, S. A Fatal Case of Non-Uremic Calciphylaxis: A Case Report and Literature Review. Am. J. Case Rep. 2018, 19, 804–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weenig, R.H.; Sewell, L.D.; Davis, M.D.; McCarthy, J.T.; Pittelkow, M.R. Calciphylaxis: Natural history, risk factor analysis, and outcome. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2007, 56, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigwekar, S.U.; Wolf, M.; Sterns, R.H.; Hix, J.K. Calciphylaxis from nonuremic causes: A systematic review. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008, 3, 1139–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, N.M.; Coates, P.T. Calcific uremic arteriolopathy: An update. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2008, 17, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, P.; Chaudet, K.M.; Nazarian, R.M.; Kroshinsky, D.; Nigwekar, S.U. Correlation between clinical and pathological features of cutaneous calciphylaxis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajih, Z.; Singer, R. Successful treatment of calciphylaxis with vitamin K in a patient on haemodialysis. Clin. Kidney J. 2022, 15, 354–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seethapathy, H.; Noureddine, L. Calciphylaxis: Approach to Diagnosis and Management. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2019, 26, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, T.; Winchester, D.S.; Davis, M.D.P.; El-Azhary, R.; Comfere, N.I. Early clinical presentations and progression of calciphylaxis. Int. J. Dermatol. 2017, 56, 856–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucca, L.J.; Moysés, R.M.A.; Lima Neto, A.S. Diagnosis and treatment of calciphylaxis in patients with chronic kidney disease. J. Bras. Nefrol. 2021, 43(4 Suppl. S1), 665–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lajoie, C.; Ghanemi, A.; Bourbeau, K.; Sidibé, A.; Wang, Y.P.; Desmeules, S.; Mac-Way, F. Multimodality approach to treat calci-phylaxis in end-stage kidney disease patients. Ren. Fail. 2023, 45, 2256413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigwekar, S.U.; Sprague, S.M. We Do Too Many Parathyroidectomies for Calciphylaxis. Semin. Dial. 2016, 29, 312–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigwekar, S.U.; Brunelli, S.M.; Meade, D.; Wang, W.; Hymes, J.; Lacson, E. Sodium thiosulfate therapy for calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 8, 1162–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo Marin, B.; Aghagoli, G.; Hu, L.S.; Massoud, M.C.; Robinson-Bostomet, L. Calciphylaxis and Kidney Disease: A Review. Am. J. Kidney Diseas. 2023, 81, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubiel-Braszczok, B.; Włoch-Targońska, M.; Jacek Kotyla, P. Calciphylaxis—Pathogenesis and clinical picture. Forum Reumatol. 2019, 5, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.F.; Denney, C.F.; Burns, D.K. Systemic calciphylaxis associated with massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 1998, 122, 656–659. [Google Scholar]

- Lafrid, M.; Labioui, N.; Hallak, M.; Bahadi, A.; El Kabbaj, D.; Allaoui, M.; Zajjari, Y. A Rare Case of Calciphylaxis: A Case Report. Biomed Hub. 2025, 10, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udomkarnjananun, S.; Kongnatthasate, K.; Praditpornsilpa, K.; Eiam-Ong, S.; Jaber, B.L.; Susantitaphong, P. Treatment ofcalci-phylaxis in CKD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Int. Rep. 2018, 4, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiriac, A.; Grosu, O.M.; Terinte, C.; Perţea, M. Calcific uremic arteriolopathy (calciphylaxis) calls into question the validity of guidelines of diagnosis and treatment. J. Dermatolog. Treat. 2020, 31, 545–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavros, K.; Motiwala, R.; Zhou, L.; Sejdiu, F.; Shin, S. Calciphylaxis in a dialysis patient diagnosed by muscle biopsy. J. Clin. Neuromusc Dis. 2014, 15, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazanji, N.; Falatko, J.; Neupane, S.; Reddy, G. Calciphylaxis presenting as digital ischemia. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2015, 10, 529–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, L.C.; Abdulnabi, K. Skin lesions in calciphylaxis. Br. J. Hosp. Med. Lond. Engl. 2016, 77, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, H.; Alotaibi, M.; Lebron, J.R. A Case Report: Calciphylaxis Presenting as Digital Ischemia in Patient with End Stage Kidney Disease on Peritoneal Dialysis. Open J. Nephrol. 2019, 9, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, K.; Araki, J.; Tokumasu, K.; Hagiya, H.; Otsuka, F. Calciphylaxis of the fingers. J. Gen. Fam. Med. 2020, 21, 25–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonchak, J.G.; Park, K.K.; Vethanayagamony, T.; Sheikh, M.M.; Winterfield, L.S. Calciphylaxis: A case series and the role of radiology in diagnosis. Int. J. Dermatol. 2016, 55, e275–e279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmer, W.A.; Magro, C.M. Calciphylaxis: Emerging concepts in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Semin. Dial. 2002, 15, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metwally, Y.; Abbas, H.; Jeyalan, V.; Khanfar, A. Calciphylaxis in a Patient on Hemodialysis: A Case Report. Cureus 2024, 16, e74558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, C.; Yang, X.; Xie, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, L.; Ye, J.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, X.; Liu, B. Prevalence and Clinical Characteristics of Calciphylaxis in Chinese Hemodialysis Patients. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 902171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, J.; Brown, E.; Podesta, A.; Troy, C.; Dong, X.E. Surgical management of calciphylaxis associated with primary hyperparathyroidism. A Case report and review of the literature. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2010, 2010, 823210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigwekar, S.U. Calciphylaxis. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2017, 26, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gossett, C.; Suppadungsuk, S.; Krisanapan, P.; Tangpanithandee, S.; Thongprayoon, C.; Mao, M.A.; Cheungpasitporn, W. Sodium Thiosulfate for Calciphylaxis Treatment in Patients on Peritoneal Dialysis: A Systematic Review. Medicina 2023, 59, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Block, G.A.; Martin, K.J.; De Francisco, A.L.; Turner, S.A.; Avram, M.M.; Suranyi, M.G.; Hercz, G.; Cunningham, J.; Abu-Alfa, A.K.; Messa, P.; et al. Cinacalcet for secondary hyperparathyroidism in patients receiving hemodialysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 1516–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigwekar, S.U. Multidisciplinary approach to calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2015, 24, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author/ Year | Sex | Age | Location | Symptoms | Diagnosis | Other Diseases | Treatment | Evolution | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Stavros K. 2014 [33] | M | 46 | arms and gluteal region | pain, myalgia, bruises, and pressure sores | clinical exam and biopsy | ESRD and HTN | parathyroidectomy, multiple surgical debridement treatments, and skin grafts | death 4 months after diagnosis |

| 2 | Kazanji N. 2015 [34] | F | 31 | D3RH | pain, livedo reticularis, cyanosis, and pressure sores | clinical exam, biopsy, and X-ray | unspecified | sodium thiosulfate and surgical treatment—unspecified | unspecified |

| 3 | Kirby L. 2016 [35] | F | 68 | arms, breast, and abdomen | unspecified | clinical exam and biopsy | ESRD | analgesics and conservative treatment for skin lesions | death 6 weeks after diagnosis |

| 4 | Abbas Hartoon 2019 [36] | F | 32 | D2RH and D3LH | pain, edema, and skin color changes | clinical exam and biopsy | ESRD | Sodium thiosulfate, cinacalcet, sevelamer care of skin lesions to prevent infection and surgical treatment—unspecified | unspecified |

| 5 | Ko Harada 2019 [37] | M | 69 | D3 and 4RH | pain, ischemia, and necrosis | clinical exam, X-ray, and biopsy | ESDR, DM, and collagen disease | discontinuation of warfarin treatment and conservative treatment of skin lesions | unspecified |

| 6 | Bielejewska A. 2020 [11] | F | 64 | fingers, hands, and toes | pain, ischemia, and necrosis | clinical exam, biopsy, and X-ray | ESRD, DM, HTA, ischemic heart disease, and ATS | Cinacalcet, Apixaban, sodium thiosulfate, and surgical treatment—left upper limb amputation | death |

| 7 | Zay Yar Aung 2022 [10] | F | 75 | D5LH, D4, and 5RH | dry gangrene | clinical exam and X-ray (no biopsy) | DM, HTN, ischemic heart disease, and hypothyroidism | unspecified (no surgery) | unspecified |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pertea, M.; Benamor, M.; Bulgaru-Iliescu, A.-I.; Abid, A.; Abid, S.; Amarandei, A.-H. Calciphylaxis of the Upper Limbs—A Rare and Serious Disease with Multidisciplinary Treatments—A Case Series and Literature Review. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1179. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15091179

Pertea M, Benamor M, Bulgaru-Iliescu A-I, Abid A, Abid S, Amarandei A-H. Calciphylaxis of the Upper Limbs—A Rare and Serious Disease with Multidisciplinary Treatments—A Case Series and Literature Review. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(9):1179. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15091179

Chicago/Turabian StylePertea, Mihaela, Malek Benamor, Andra-Irina Bulgaru-Iliescu, Abderrazek Abid, Said Abid, and Alexandru-Hristo Amarandei. 2025. "Calciphylaxis of the Upper Limbs—A Rare and Serious Disease with Multidisciplinary Treatments—A Case Series and Literature Review" Diagnostics 15, no. 9: 1179. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15091179

APA StylePertea, M., Benamor, M., Bulgaru-Iliescu, A.-I., Abid, A., Abid, S., & Amarandei, A.-H. (2025). Calciphylaxis of the Upper Limbs—A Rare and Serious Disease with Multidisciplinary Treatments—A Case Series and Literature Review. Diagnostics, 15(9), 1179. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15091179