Increased Musculoskeletal Surgery Rates During Diagnostic Delay in Psoriatic Arthritis: A Retrospective Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patients

2.2. Collection of MSK Surgery and Other Clinical Data

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data/Baseline Characteristics

3.2. MSK Operation Data

3.3. Subgroup Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| bDMARD | Biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug |

| csDMARD | Conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug |

| ESR | Erythrocyte sedimentation rate |

| MSK | Musculoskeletal system |

| MTX | Methotrexate |

| NSAID | Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug |

| PsA | Psoriatic arthritis |

| PsO | Psoriasis |

| RA | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| SpA | Spondyloarthritis |

References

- Ogdie, A.; Weiss, P. The Epidemiology of Psoriatic Arthritis. Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 41, 545–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alascio, L.; Azuaga-Piñango, A.B.; Frade-Sosa, B.; Sarmiento-Monroy, J.C.; Ponce, A.; Farietta, S.; Gómez-Puerta, J.A.; Sanmartí, R.; Cañete, J.D.; Ramírez, J. Axial Disease in Psoriatic Arthritis: A Challenging Domain in Clinical Practice. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmungil, H.; İlgen, U.; Direskeneli, R.H. Autoimmunity in Psoriatic Arthritis: Pathophysiological and Clinical Aspects. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 51, 1601–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchlin, C.T.; Colbert, R.A.; Gladman, D.D. Psoriatic Arthritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 957–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogdie, A.; Coates, L.C.; Mease, P. Measuring Outcomes in Psoriatic Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2020, 72 (Suppl. S10), 82–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogdie, A.; Nowell, W.B.; Applegate, E.; Gavigan, K.; Venkatachalam, S.; de la Cruz, M.; Flood, E.; Schwartz, E.J.; Romero, B.; Hur, P. Patient Perspectives on the Pathway to Psoriatic Arthritis Diagnosis: Results from a Web-Based Survey of Patients in the United States. BMC Rheumatol. 2020, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gossec, L.; Kerschbaumer, A.; Ferreira, R.J.O.; Aletaha, D.; Baraliakos, X.; Bertheussen, H.; Boehncke, W.H.; Esbensen, B.A.; McInnes, I.B.; McGonagle, D.; et al. EULAR Recommendations for the Management of Psoriatic Arthritis with Pharmacological Therapies: 2023 Update. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2024, 83, 706–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerschbaumer, A.; Smolen, J.S.; O Ferreira, R.J.; Bertheussen, H.; Baraliakos, X.; Aletaha, D.; McGonagle, D.G.; van der Heijde, D.; McInnes, I.B.; Esbensen, B.A.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Pharmacological Treatment of Psoriatic Arthritis: A Systematic Literature Research Informing the 2023 Update of the EULAR Recommendations for the Management of Psoriatic Arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2024, 83, 760–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogdie, A. The Preclinical Phase of PsA: A Challenge for the Epidemiologist. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 76, 1481–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, L.E.; Jørgensen, T.S.; Christensen, R.; Gudbergsen, H.; Dreyer, L.; Ballegaard, C.; Jacobsson, L.T.H.; Strand, V.; Mease, P.J.; Kjellberg, J. Societal Costs and Patients’ Experience of Health Inequities Before and After Diagnosis of Psoriatic Arthritis: A Danish Cohort Study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 76, 1495–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caso, F.; Costa, L.; Megna, M.; Cascone, M.; Maione, F.; Giacomelli, R.; Scarpa, R.; Ruscitti, P. Early Psoriatic Arthritis: Clinical and Therapeutic Challenges. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2024, 33, 945–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangger, P.; Esufali, Z.H.; Gladman, D.D.; Bogoch, E.R. Type and Outcome of Reconstructive Surgery for Different Patterns of Psoriatic Arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 2000, 27, 967–974. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kwok, T.S.H.; Sutton, M.; Cook, R.J.; Pereira, D.; Chandran, V.; Gladman, D.D. Musculoskeletal Surgery in Psoriatic Arthritis: Prevalence and Risk Factors. J. Rheumatol. 2023, 50, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaffi, J.; Bianchi, L.; Di Martino, A.; Faldini, C.; Ursini, F. Is Total Joint Arthroplasty an Effective and Safe Option for Psoriatic Arthritis Patients? A Scoping Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucchelli, R.; Almodóvar, R.; Turrado-Crespí, P.; Crespí-Villarías, N.; Pérez-Fernández, E.; García-Zamora, E.; García-Vadillo, A. Trends in Orthopaedic Surgery for Spondyloarthritis: Outcomes from a National Hospitalised Patient Registry (MBDS) over a 17-Year Period (1999–2015). RMD Open 2022, 8, e002107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guldberg-Møller, J.; Cordtz, R.L.; Kristensen, L.E.; Dreyer, L. Incidence and Time Trends of Joint Surgery in Patients with Psoriatic Arthritis: A Register-Based Time Series and Cohort Study from Denmark. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2019, 78, 1517–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangger, P.; Gladman, D.D.; Bogoch, E.R. Musculoskeletal Surgery in Psoriatic Arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 1998, 25, 725–729. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, N.; Lories, R.J.; de Vlam, K. Orthopaedic Interventions in Patients with Psoriatic Arthritis: A Descriptive Report from the SPAR Cohort. RMD Open 2016, 2, e000293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michet, C.J.; Mason, T.G.; Mazlumzadeh, M. Hip Joint Disease in Psoriatic Arthritis: Risk Factors and Natural History. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2005, 64, 1068–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsky, M.R.; Feldon, P.; Millender, L.H.; Nalebuff, E.A.; Phillips, C. Hand Involvement in Psoriatic Arthritis. J. Hand Surg. Am. 1982, 7, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, E.J.; Alfonso, D.; Baidwan, G.; Di Cesare, P.E. Orthopedic Manifestations and Management of Psoriatic Arthritis. Am. J. Orthop. 2008, 37, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McHugh, N.J.; Balachrishnan, C.; Jones, S.M. Progression of Peripheral Joint Disease in Psoriatic Arthritis: A 5-Year Prospective Study. Rheumatology 2003, 42, 778–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kılıç, G.; Kılıç, E.; Tekeoğlu, İ.; Sargın, B.; Cengiz, G.; Balta, N.C.; Alkan, H.; Kasman, S.A.; Şahin, N.; Orhan, K.; et al. Diagnostic Delay in Psoriatic Arthritis: Insights from a Nationwide Multicenter Study. Rheumatol. Int. 2024, 44, 1051–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, J.; Hetland, M.L.; All Departments of Rheumatology in Denmark. Diagnostic Delay in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis, Psoriatic Arthritis and Ankylosing Spondylitis: Results from the Danish Nationwide DANBIO Registry. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015, 74, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haroon, M.; Gallagher, P.; Fitzgerald, O. Diagnostic Delay of More than 6 Months Contributes to Poor Radiographic and Functional Outcome in Psoriatic Arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015, 74, 1045–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulabchand, R.; Mouterde, G.; Barnetche, T.; Lukas, C.; Morel, J.; Combe, B. Effect of Tumour Necrosis Factor Blockers on Radiographic Progression of Psoriatic Arthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 73, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajevardi, V.; Ghodsi, S.Z.; Shafiei, M.; Teimourpour, A.; Etesami, I. Evaluating the Persian Versions of Two Psoriatic Arthritis Screening Questionnaires Early Arthritis for Psoriatic Patients Questionnaire (EARP) and Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) in Iranian Psoriatic Patients. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 51, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 47 ± 11 |

| Female/male, N (%) | 74 (88.1)/10 (11.9) |

| Duration of symptoms before diagnosis (years), mean ± SD (max–min) | 7.49 ± 8.12 (1–50) |

| PsA duration (years), mean ± SD | 3.39 ± 4.26 |

| Involvement site (axial/peripheral/axial + peripheral), N (%) | 11 (13.1)/9 (10.7)/64 (76.2) |

| Psoriasis duration (years), mean ± SD | 8.31 ± 8.33 |

| Psoriasis (skin involvement), N (%) | 35 (41.7) |

| Psoriasis (nail involvement), N (%) | 28 (33.3) |

| Family history of psoriasis, N (%) | 41 (48.8) |

| Patients with at least one MSK surgery, N (%) | 23 (27.4) |

| Pre-Diagnostic Symptomatic Period | Post-Diagnosis Period | p-Value † | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients with at least one MSK surgery, N (%) | 21 (25%) | 3 (3.6%) | 0.583 a |

| Patients with one MSK surgery, N (%) | 8 (9.5%) | 3 (3.6%) | - |

| Patients with ≥2 MSK surgeries, N (%) | 13 (15.5%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| MSK surgeries per patient, median (range) | 0 (0–5) | 0 (0–1) | <0.001 b (Z = −3.952) |

| Annual MSK surgeries per patient, median (range) | 0 (0–1.67) | 0 (0–1) | 0.001 b (Z = −3.182) |

| Surgical Sites | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Peripheral (total) * | 22 | 52.4 |

| • Knee ** | 15 | 35.7 |

| • Ankle | 2 | 4.8 |

| • Hip | 2 | 4.8 |

| • Wrist | 2 | 4.8 |

| • Elbow | 1 | 2.4 |

| Spine (total) | 20 | 47.6 |

| • Lumbar disc operations | 12 | 28.6 |

| • Other spine procedures (vertebral fracture, spondylolisthesis, vertebroplasty, stabilisation, etc.) | 8 | 19.0 |

| Total | 42 | 100.0 |

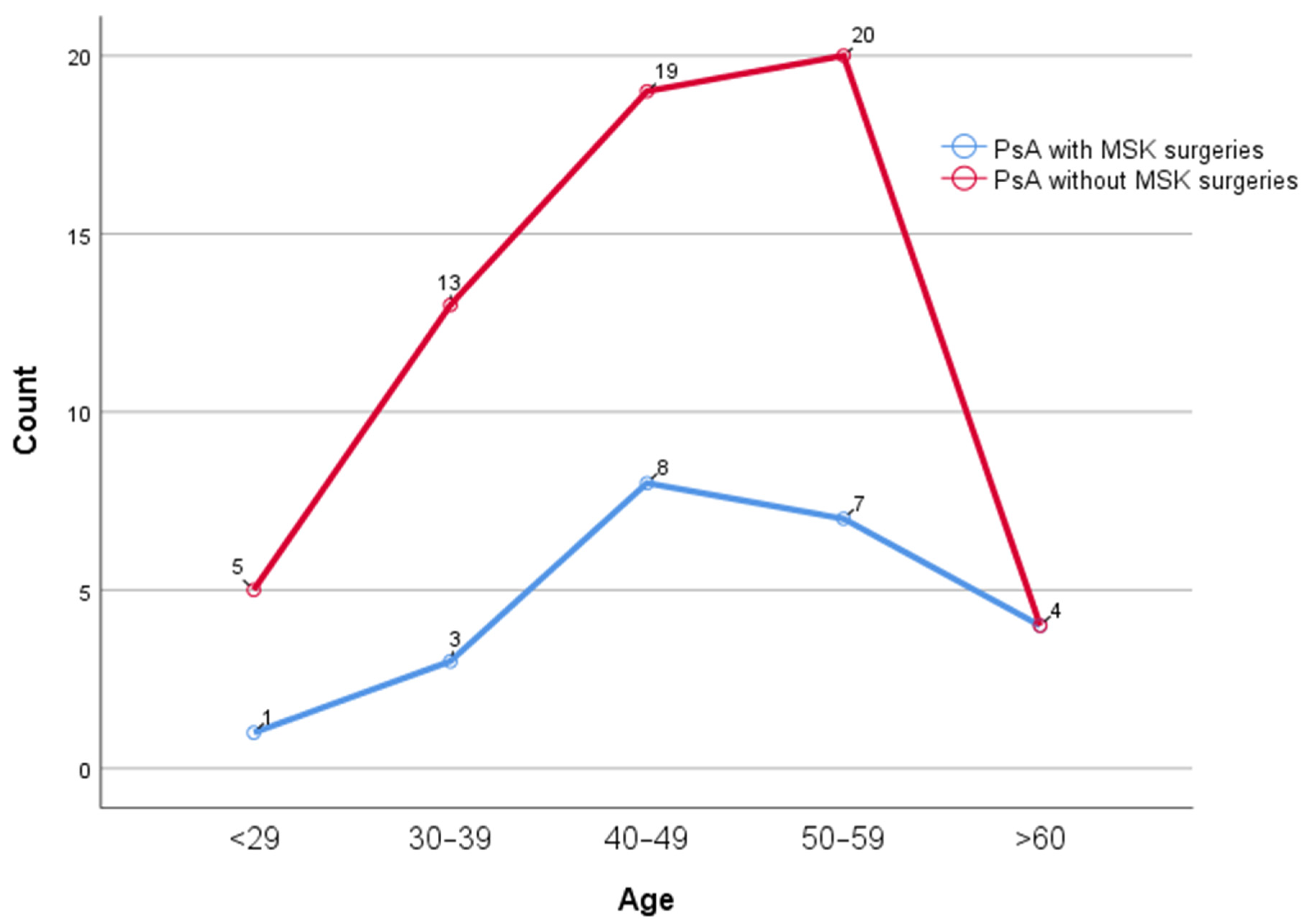

| Variable | PsA with MSK Surgeries | PsA Without MSK Surgeries | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), Mean ± SD | 49.4 ± 10.9 | 46.2 ± 11.6 | 0.257 |

| Female/Male, N (%) | 21 (91.3)/2 (8.7) | 53 (86.9)/8 (313.1) | 0.577 |

| Axial involvement, N (%) | 3 (13) | 8 (13.1) | 0.916 |

| Peripheral involvement, N (%) | 3 (13) | 6 (9.8) | |

| Axial and peripheral involvement, N (%) | 17 (73.9) | 47 (77) | |

| Duration of symptoms before diagnosis (years), Mean ± SD (max–min) | 8.2 ± 8.4 | 7 ± 6.7 | 0.516 |

| PsA duration (years), Mean ± SD | 2.8 ± 2.1 | 3.6 ± 4.8 | 0.493 |

| Psoriasis duration (years), Mean ± SD | 10.1 ± 8.9 | 7.6 ± 8.1 | 0.431 |

| Psoriasis (skin involvement), N (%) | 10 (43.5) | 25 (41) | 0.836 |

| Psoriasis (nail involvement), N (%) | 10 (43.5) | 18 (29.5) | 0.226 |

| Family history of psoriasis, N (%) | 13 (56.5) | 28 (45.9) | 0.611 |

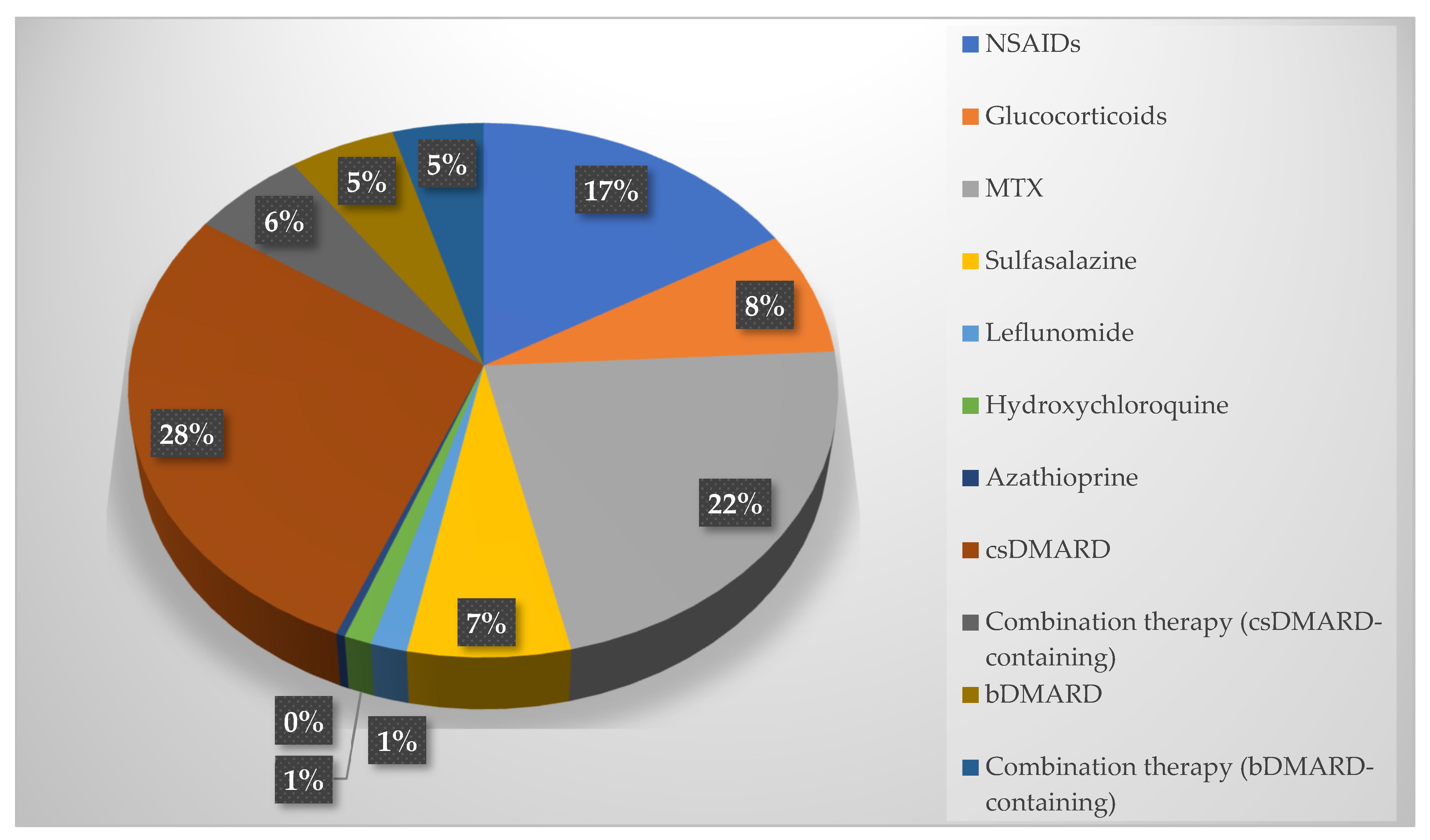

| Medications Used | |||

| NSAIDs, N (%) | 15 (65.2) | 29 (47.5) | 0.148 |

| Glucocorticoids, N (%) | 6 (26.1) | 14 (23) | 0.763 |

| Methotrexate, N (%) | 20 (87) | 39 (63.9) | 0.040 |

| Sulfasalazine, N (%) | 2 (8.7) | 16 (26.2) | 0.134 |

| Leflunomide, N (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (6.6) | - |

| Hydroxychloroquine, N (%) | 1 (4.3) | 2 (3.3) | - |

| Azathioprine, N (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) | - |

| csDMARD, N (%) | 21 (91.3) | 54 (88.5) | 0.713 |

| Combination therapy (csDMARD-containing), N (%) | 6 (26.1) | 9 (14.8) | 0.227 |

| Biologic DMARD, N (%) | 1 (4.3) | 13 (21.3) | 0.063 |

| Combination therapy (bDMARD-containing), N (%) | 2 (8.7) | 10 (16.4) | 0.369 |

| Variables | Gender | Sites of MSK Involvement | Family History of Psoriasis | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | p * | Male | p * | Axial | p * | Peripheral | p * | Axial + Peripheral | p * | Yes | p * | No | p * | |||

| Presence of MSK surgery | Pre- diagnosis | Yes | 19 (25.68) | <0.001 | 2 (20.00) | 0.5 | 3 (27.27) | 0.250 | 2 (22.22) | 16 (25.00) | 0.001 | 8 (18.60) | 0.109 | 13 (31.71) | <0.001 | |

| No | 55 (74.32) | 8 (80.00) | 8 (72.73) | 7 (77.78) | 48 (75.00) | 35 (81.40) | 28 (68.29) | |||||||||

| Post- diagnosis | Yes | 3 (4.05) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (11.11) | 2 (3.13) | 2 (4.65) | 1 (2.44) | ||||||||

| No | 71 (95.95) | 10 (100.00) | 11 (100.00) | 8 (88.89) | 62 (96.88) | 41 (95.35) | 40 (97.56) | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yolbas, S.; Gündüz, İ.; Kara, M.; Çay, E.; Yamancan, G.; Yalçın, N.; İnanç, E.; Zontul, S.; Köroğlu, M. Increased Musculoskeletal Surgery Rates During Diagnostic Delay in Psoriatic Arthritis: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15091125

Yolbas S, Gündüz İ, Kara M, Çay E, Yamancan G, Yalçın N, İnanç E, Zontul S, Köroğlu M. Increased Musculoskeletal Surgery Rates During Diagnostic Delay in Psoriatic Arthritis: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(9):1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15091125

Chicago/Turabian StyleYolbas, Servet, İlyas Gündüz, Mahmut Kara, Emrah Çay, Gülşah Yamancan, Nevra Yalçın, Elif İnanç, Sezgin Zontul, and Muhammed Köroğlu. 2025. "Increased Musculoskeletal Surgery Rates During Diagnostic Delay in Psoriatic Arthritis: A Retrospective Cohort Study" Diagnostics 15, no. 9: 1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15091125

APA StyleYolbas, S., Gündüz, İ., Kara, M., Çay, E., Yamancan, G., Yalçın, N., İnanç, E., Zontul, S., & Köroğlu, M. (2025). Increased Musculoskeletal Surgery Rates During Diagnostic Delay in Psoriatic Arthritis: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Diagnostics, 15(9), 1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15091125