Prostate Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment in Elderly Patients: A Cross-Sectional Survey Exploring Practice Patterns and Preferences of Uro-Oncologists in Northeast Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of Responders

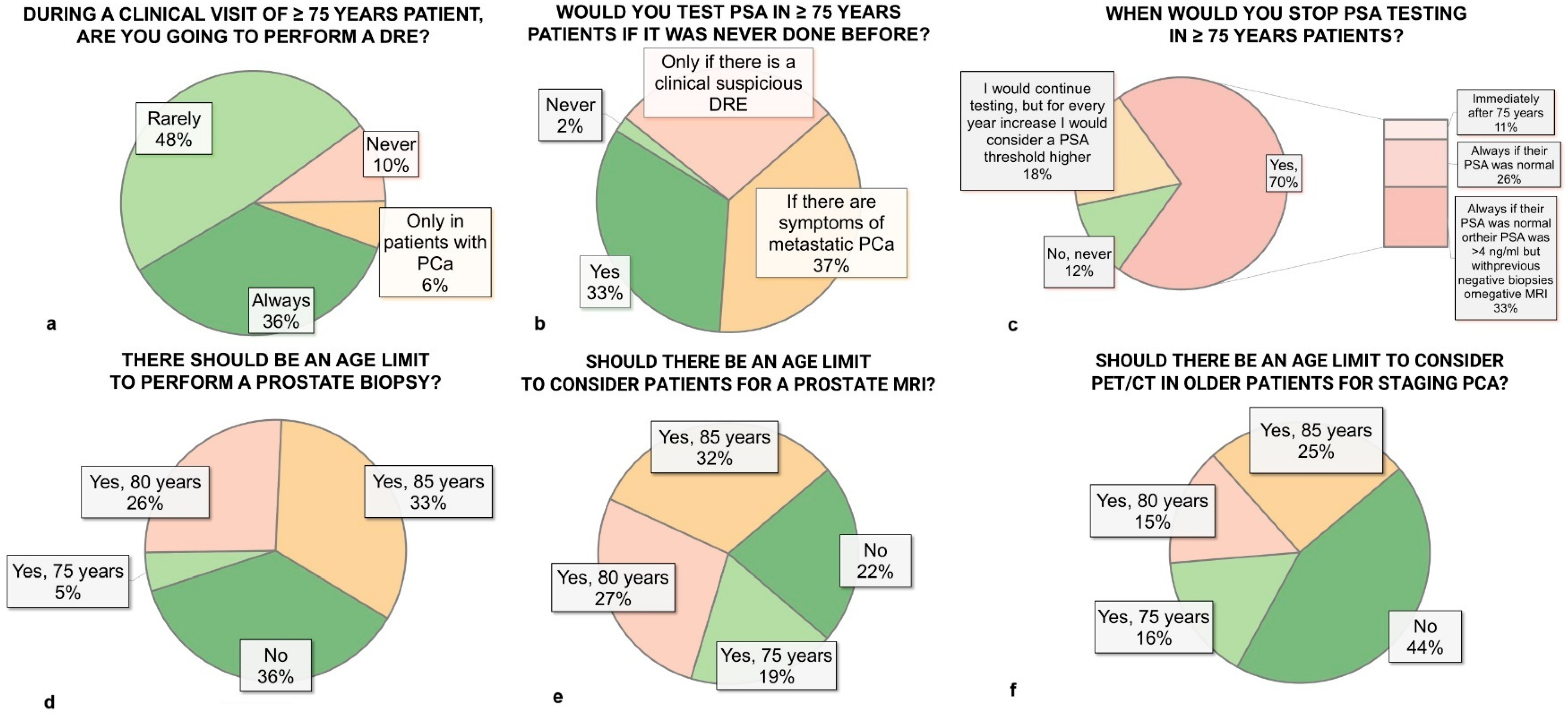

3.2. Digital Rectal Examination and PSA Testing

3.3. Prostate Biopsy

3.4. Imaging

3.5. Life Expectancy and Comorbidity Assessment Tools

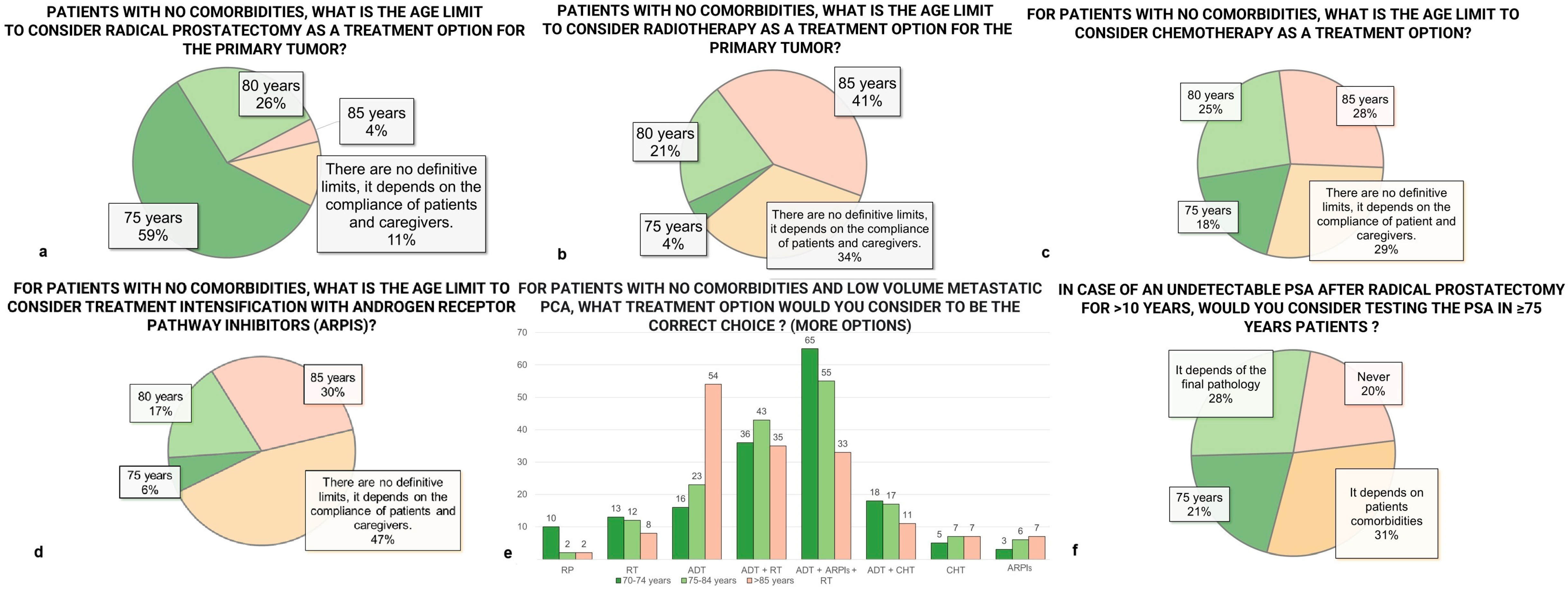

3.6. Treatment Options

3.7. Systemic Therapy

3.8. Follow-Up

3.9. Clinical Trial Participation

3.10. Communication Practices

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCa | Prostate cancer |

| ARPIs | Androgen receptor pathway inhibitors |

| CGA | comprehensive geriatric assessment |

| SIOG | International Society of Geriatric Oncology |

| DRE | Digital Rectal examination |

| ADT | Androgen Deprivation Therapy |

| RT | Radiotherapy |

| RP | Radical Prostatectomy |

| EP | Experienced Physicians |

References

- James, N.D.; Tannock, I.; N’Dow, J.; Feng, F.; Gillessen, S.; Ali, S.A.; Trujillo, B.; Al-Lazikani, B.; Attard, G.; Bray, F.; et al. The Lancet Commission on prostate cancer: Planning for the surge in cases. Lancet 2024, 403, 1683–1722. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38583453/ (accessed on 6 December 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawla, P. Epidemiology of Prostate Cancer. World J. Oncol. 2019, 10, 63. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6497009/ (accessed on 10 November 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vatandoust, S.; Kichenadasse, G.; O’Callaghan, M.; Vincent, A.D.; Kopsaftis, T.; Walsh, S.; Borg, M.; Karapetis, C.S.; Moretti, K. Localised prostate cancer in elderly men aged 80–89 years, findings from a population-based registry. BJU Int. 2018, 121 (Suppl. 3), 48–54. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29603585/ (accessed on 11 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Bratt, O.; Folkvaljon, Y.; Eriksson, M.H.; Akre, O.; Carlsson, S.; Drevin, L.; Lissbrant, I.F.; Makarov, D.; Loeb, S.; Stattin, P. Undertreatment of Men in Their Seventies with High-risk Nonmetastatic Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2015, 68, 53–58. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25813688/ (accessed on 11 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Graham, L.S.; Lin, J.K.; Lage, D.E.; Kessler, E.R.; Parikh, R.B.; Morgans, A.K. Management of Prostate Cancer in Older Adults. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. B 2023, 43, e390396. Available online: https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/EDBK_390396 (accessed on 10 November 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bin Riaz, I.; Islam, M.; Ikram, W.; Naqvi, S.A.A.; Maqsood, H.; Saleem, Y.; Riaz, A.; Ravi, P.; Wang, Z.; Hussain, S.A.; et al. Disparities in the Inclusion of Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups and Older Adults in Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 180–187. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36416812/ (accessed on 10 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Droz, J.-P.; Balducci, L.; Bolla, M.; Emberton, M.; Fitzpatrick, J.M.; Joniau, S.; Kattan, M.W.; Monfardini, S.; Moul, J.W.; Naeim, A.; et al. Background for the proposal of SIOG guidelines for the management of prostate cancer in senior adults. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2010, 73, 68–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droz, J.-P.; Aapro, M.; Balducci, L.; Boyle, H.; Broeck, T.V.D.; Cathcart, P.; Dickinson, L.; Efstathiou, E.; Emberton, M.; Fitzpatrick, J.M.; et al. Management of prostate cancer in older patients: Updated recommendations of a working group of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, e404–e414. Available online: http://www.thelancet.com/article/S147020451470018X/fulltext (accessed on 10 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Mottet, N.; Bellmunt, J.; Briers, E.; Bolla, M.; Bourke, L.; Cornford, P.; De Santis, M.; Henry, A.M.; Joniau, S.; Lam, T.B.; et al. EAU Guidelines on Prostate Cancer 2017; European Association of Urology: Arnhem, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 1–146. [Google Scholar]

- Cornford, P.; van den Bergh, R.C.N.; Briers, E.; Van den Broeck, T.; Brunckhorst, O.; Darraugh, J.; Eberli, D.; De Meerleer, G.; De Santis, M.; Farolfi, A.; et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer—2024 Update. Part I: Screening, Diagnosis, and Local Treatment with Curative Intent. Eur. Urol. 2024, 86, 148–163. Available online: http://www.europeanurology.com/article/S0302283824022541/fulltext (accessed on 6 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Tilki, D.; van den Bergh, R.C.N.; Briers, E.; Van den Broeck, T.; Brunckhorst, O.; Darraugh, J.; Eberli, D.; De Meerleer, G.; De Santis, M.; Farolfi, A.; et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. Part II—2024 Update: Treatment of Relapsing and Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2024, 86, 164–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droz, J.P.; Boyle, H.; Albrand, G.; Mottet, N.; Puts, M. Role of Geriatric Oncologists in Optimizing Care of Urological Oncology Patients. Eur. Urol. Focus. 2017, 3, 385–394. Available online: http://www.eu-focus.europeanurology.com/article/S2405456917302523/fulltext (accessed on 10 November 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, H.; Alibhai, S.; Decoster, L.; Efstathiou, E.; Fizazi, K.; Mottet, N.; Oudard, S.; Payne, H.; Prentice, M.; Puts, M.; et al. Updated recommendations of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology on prostate cancer management in older patients. Eur. J. Cancer 2019, 116, 116–136. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31195356/ (accessed on 11 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Dale, W.; Williams, G.R.; MacKenzie, A.R.; Soto-Perez-De-Celis, E.; Maggiore, R.J.; Merrill, J.K.; Katta, S.; Smith, K.T.; Klepin, H.D. How Is Geriatric Assessment Used in Clinical Practice for Older Adults With Cancer? A Survey of Cancer Providers by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2021, 17, 336–344. Available online: https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/OP.20.00442 (accessed on 10 November 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldini, C.; Brain, E.G.C.; Rostoft, S.; Biganzoli, L.; Goede, V.; Kanesvaran, R.; Quoix, E.; Steer, C.; Papamichael, D.; Wildiers, H. 1827P European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO)/International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) Joint Working Group (WG) survey on management of older patients with cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, S1237–S1238. Available online: http://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923753421029446/fulltext (accessed on 10 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Cherny, N.I.; de Vries, E.G.; Dafni, U.; Garrett-Mayer, E.; McKernin, S.E.; Piccart, M.; Latino, N.J.; Douillard, J.-Y.; Schnipper, L.E.; Somerfield, M.R.; et al. ESMO-Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale version 1.1. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2017, 28, 2340–2366. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28945867/ (accessed on 11 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1459–1544. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27733281/ (accessed on 18 November 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDCP. Trends in Aging—United States and Worldwide. Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 2003, 52, 106. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12645839/ (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Schaeffer, E.M.; Carter, H.B.; Kettermann, A.; Loeb, S.; Ferrucci, L.; Landis, P.; Trock, B.J.; Metter, E.J. Prostate Specific Antigen Testing Among the Elderly—When To Stop? J. Urol. 2009, 181, 1606. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2668165/ (accessed on 18 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- de Vos, I.I.; Remmers, S.; Hogenhout, R.; Roobol, M.J. Prostate Cancer Mortality Among Elderly Men After Discontinuing Organised Screening: Long-term Results from the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer Rotterdam. Eur. Urol. 2024, 85, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, S.V.; de Carvalho, T.M.; Roobol, M.J.; Hugosson, J.; Auvinen, A.; Kwiatkowski, M.; Villers, A.; Zappa, M.; Nelen, V.; Páez, A.; et al. Estimating the harms and benefits of prostate cancer screening as used in common practice versus recommended good practice: A microsimulation screening analysis. Cancer 2016, 122, 3386–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kensler, K.H.; Mao, J.; Davuluri, M. Frequency of Guideline-Discordant Prostate Cancer Screening Among Older Males. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e248487. Available online: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2818096 (accessed on 29 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, S.V.; Oh, W.K. How Can Guidelines Give Clearer Guidance on Prostate Cancer Screening? JAMA Oncol. 2024, 10, 1497–1498. Available online: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaoncology/fullarticle/2824195 (accessed on 18 November 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drost, F.-J.H.; Osses, D.; Nieboer, D.; Bangma, C.H.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Roobol, M.J.; Schoots, I.G. Prostate Magnetic Resonance Imaging, with or Without Magnetic Resonance Imaging-targeted Biopsy, and Systematic Biopsy for Detecting Prostate Cancer: A Cochrane Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Eur. Urol. 2020, 77, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krausewitz, P.; Borkowetz, A.; Ortner, G.; Kornienko, K.; Wenzel, M.; Westhoff, N. Do we need MRI in all biopsy naïve patients? A multicenter cohort analysis. World J. Urol. 2024, 42, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, R.; Jeet, V.; Sharma, R.; Hoyle, M.; Parkinson, B. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen (PSMA) Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography (PET/CT) for the Primary Staging of Prostate Cancer in Australia. Pharmacoeconomics 2022, 40, 807. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9300561/ (accessed on 19 November 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Sar, E.C.A.; Keusters, W.R.; van Kalmthout, L.W.M.; Braat, A.J.A.T.; de Keizer, B.; Frederix, G.W.J.; Kooistra, A.; Lavalaye, J.; Lam, M.G.E.H.; van Melick, H.H.E. Cost-effectiveness of the implementation of [68Ga]Ga-PSMA-11 PET/CT at initial prostate cancer staging. Insights Imaging 2022, 13, 132. Available online: https://insightsimaging.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s13244-022-01265-w (accessed on 19 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Prior, J.O.; Gillessen, S.; Wirth, M.; Dale, W.; Aapro, M.; Oyen, W.J.G. Radiopharmaceuticals in the elderly cancer patient: Practical considerations, with a focus on prostate cancer therapy: A position paper from the International Society of Geriatric Oncology Task Force. Eur. J. Cancer 2017, 77, 127–139. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28391026/ (accessed on 26 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Mandel, P.; Chandrasekar, T.; Chun, F.K.; Huland, H.; Tilki, D. Radical prostatectomy in patients aged 75 years or older: Review of the literature. Asian J. Androl. 2017, 21, 32. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6337955/ (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Dell’Oglio, P.; Zaffuto, E.; Boehm, K.; Trudeau, V.; Larcher, A.; Tian, Z.; Moschini, M.; Shariat, S.; Graefen, M.; Saad, F.; et al. Long-term survival of patients aged 80 years or older treated with radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 43, 1581–1588. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28330822/ (accessed on 19 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Marotte, D.; Chand-Fouche, M.E.; Boulahssass, R.; Hannoun-Levi, J.M. Irradiation of localized prostate cancer in the elderly: A systematic literature review. Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol. 2022, 35, 1–8. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9046879/ (accessed on 19 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, F.E.; Robinson, D.; Bratt, O.; Fallara, G.; Lambe, M.; Johansson, A.L.V. Time trends in the use of curative treatment in men 70 years and older with nonmetastatic prostate cancer. Acta Oncol. 2024, 63, 26189. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11332516/ (accessed on 19 November 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carletti, F.; Reitano, G.; Evangelista, L.; Alongi, F.; Antonelli, A.; Basso, U.; Bortolus, R.; Brunelli, M.; Caffo, O.; Dal Moro, F.; et al. Prostate Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment in Elderly Patients: A Cross-Sectional Survey Exploring Practice Patterns and Preferences of Uro-Oncologists in Northeast Italy. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1100. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15091100

Carletti F, Reitano G, Evangelista L, Alongi F, Antonelli A, Basso U, Bortolus R, Brunelli M, Caffo O, Dal Moro F, et al. Prostate Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment in Elderly Patients: A Cross-Sectional Survey Exploring Practice Patterns and Preferences of Uro-Oncologists in Northeast Italy. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(9):1100. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15091100

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarletti, Filippo, Giuseppe Reitano, Laura Evangelista, Filippo Alongi, Alessandro Antonelli, Umberto Basso, Roberto Bortolus, Matteo Brunelli, Orazio Caffo, Fabrizio Dal Moro, and et al. 2025. "Prostate Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment in Elderly Patients: A Cross-Sectional Survey Exploring Practice Patterns and Preferences of Uro-Oncologists in Northeast Italy" Diagnostics 15, no. 9: 1100. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15091100

APA StyleCarletti, F., Reitano, G., Evangelista, L., Alongi, F., Antonelli, A., Basso, U., Bortolus, R., Brunelli, M., Caffo, O., Dal Moro, F., De Vivo, R., Gardi, M., Girometti, R., Guttilla, A., Matrone, F., Salgarello, M., Signor, M. A., Zattoni, F., Giannarini, G., & on behalf of Gruppo Uro-Oncologico del Nord Est (GUONE). (2025). Prostate Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment in Elderly Patients: A Cross-Sectional Survey Exploring Practice Patterns and Preferences of Uro-Oncologists in Northeast Italy. Diagnostics, 15(9), 1100. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15091100