Shape-Sensing Robotic-Assisted Bronchoscopic Microwave Ablation for Primary and Metastatic Pulmonary Nodules: Retrospective Case Series

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patients

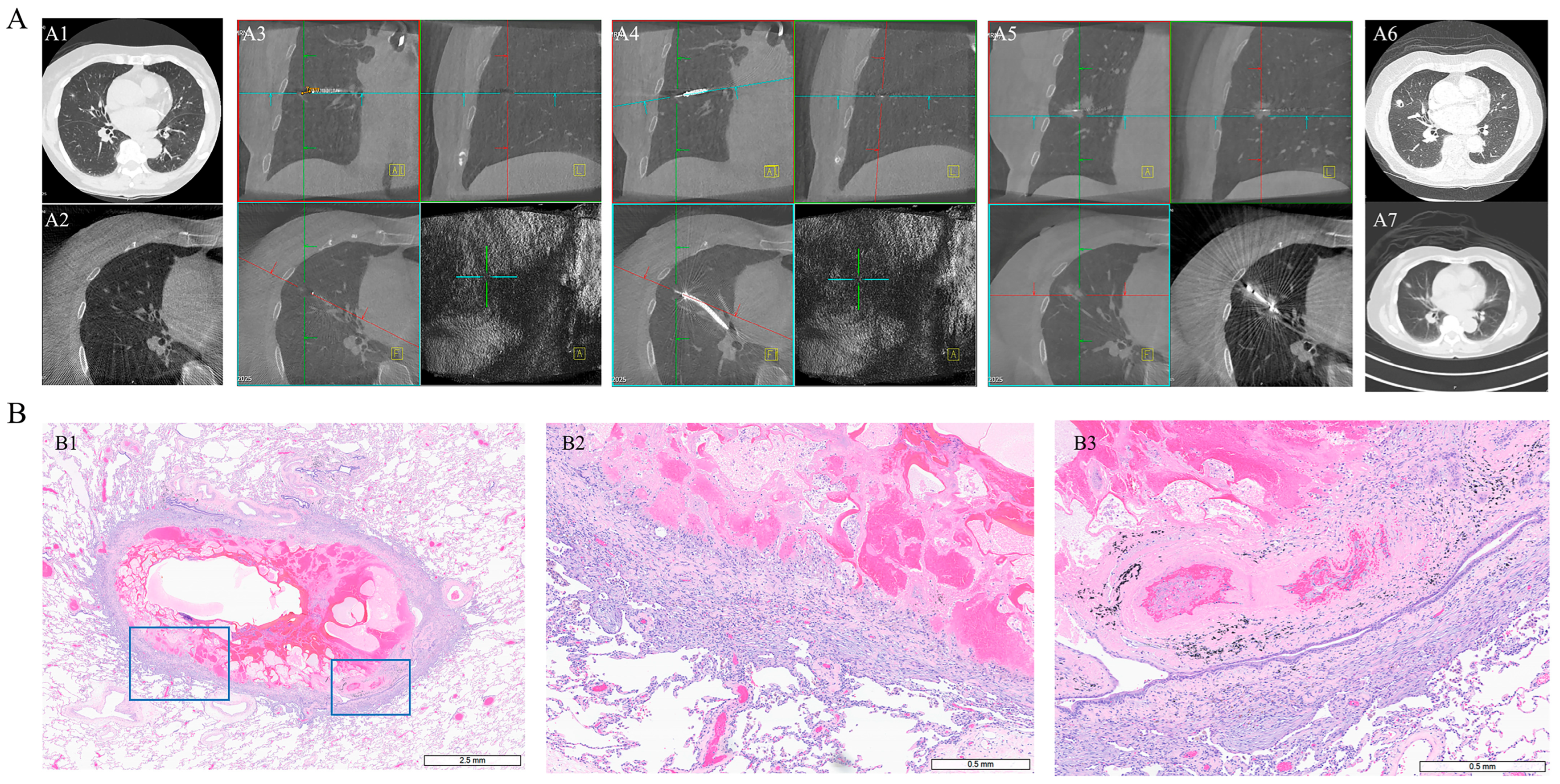

2.2. Pre-Procedure Planning and Procedure

2.3. Post-Procedure Care and Follow-Up

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient and Lesion Characteristics

3.2. Technical Outcomes

3.3. Safety and Complications

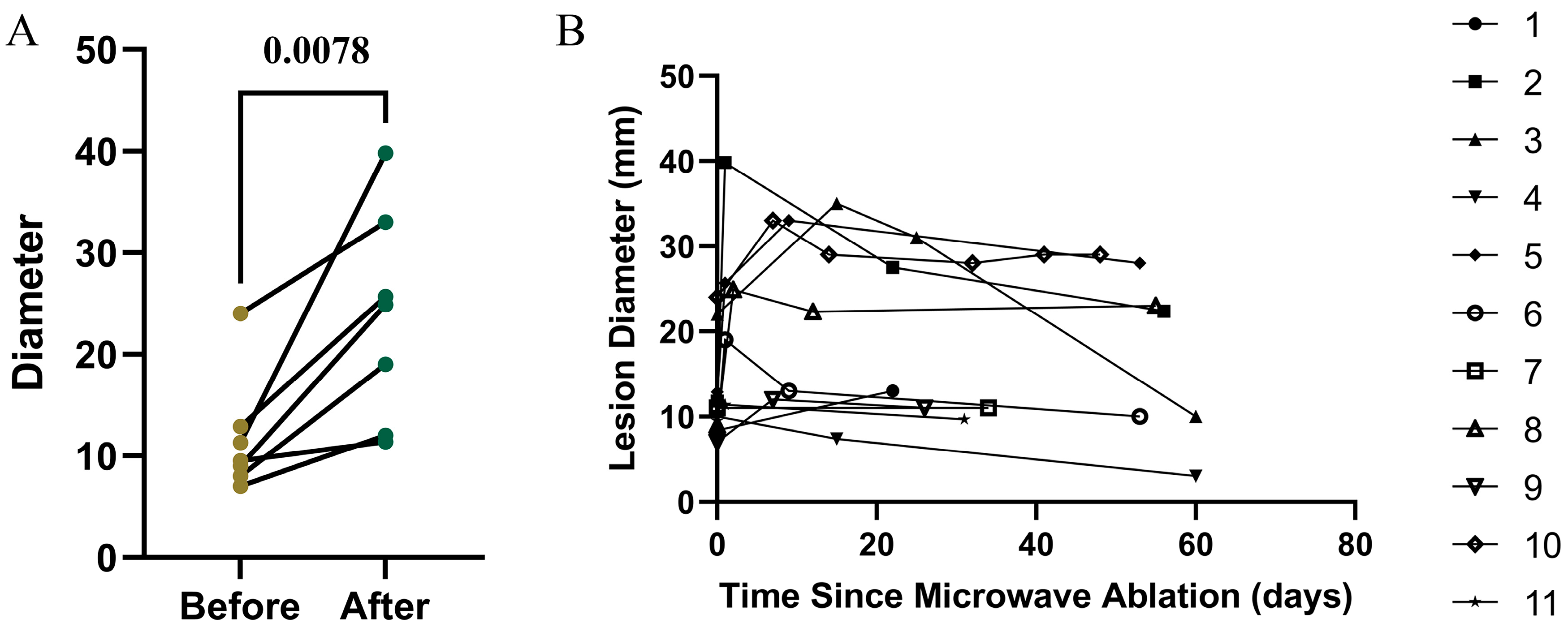

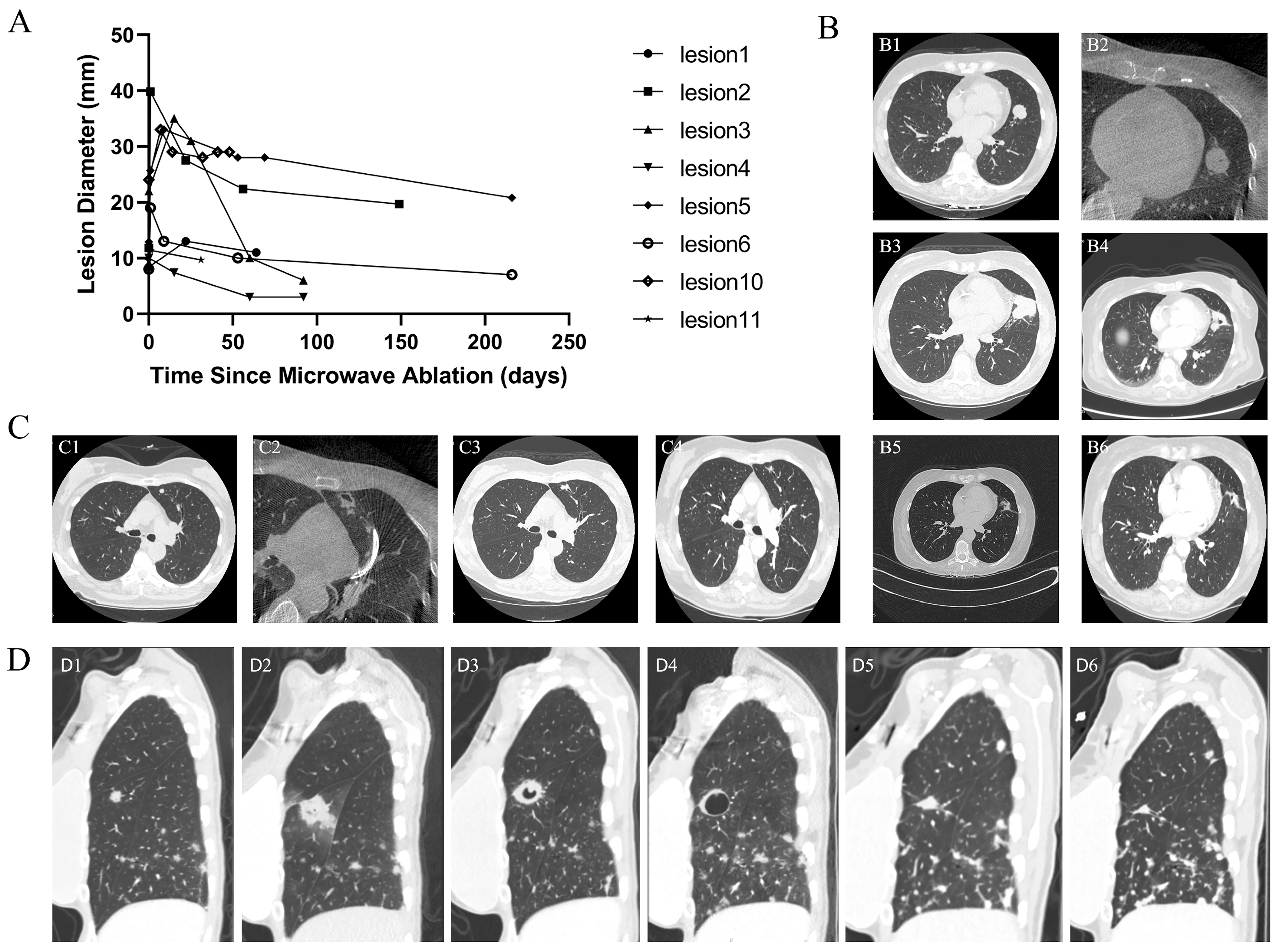

3.4. Imaging Evolution After Ablation

3.5. Efficacy of Microwave Ablation for Primary Lung Cancer

3.6. Early Efficacy of Microwave Ablation for Metastatic Lung Lesions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leiter, A.; Veluswamy, R.R.; Wisnivesky, J.P. The global burden of lung cancer: Current status and future trends. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 20, 624–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, A.; Kasi, A. Lung Metastasis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553111/ (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Araujo-Filho, J.A.B.; Halpenny, D.; McQuade, C.; Puthoff, G.; Chiles, C.; Nishino, M.; Ginsberg, M.S. Management of pulmonary nodules in oncologic patients: AJR Expert Panel Narrative Review. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2021, 216, 1423–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerull, W.D.; Puri, V.; Kozower, B.D. The epidemiology and biology of pulmonary metastases. J. Thorac. Dis. 2021, 13, 2585–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howington, J.A.; Blum, M.G.; Chang, A.C.; Balekian, A.A.; Murthy, S.C. Treatment of stage I and II non-small cell lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2013, 143, e278S–e313S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, P.B.; Cramer, L.D.; Warren, J.L.; Begg, C.B. Racial differences in the treatment of early-stage lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geevarghese, R.; Alexander, E.S.; Elsakka, A.; Chevallier, O.; Kelly, L.; Sotirchos, V.S.; Sofocleous, C.T.; Petre, E.N.; Erinjeri, J.P.; Zhan, C.; et al. Outcomes following microwave ablation of 669 primary and metastatic lung malignancies. Eur. Radiol. 2025; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®): Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 8.2025; National Comprehensive Cancer Network: Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/guidelines (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Smith, S.L.; Jennings, P.E. Lung radiofrequency and microwave ablation: A review of indications, techniques and post-procedural imaging appearances. Br. J. Radiol. 2015, 88, 20140598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vita, E.; Lo Presti, D.; Massaroni, C.; Iadicicco, A.; Schena, E.; Campopiano, S. A review on radiofrequency, laser, and microwave ablations and their thermal monitoring through fiber Bragg gratings. iScience 2023, 26, 108260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curto, S.; Taj-Eldin, M.; Fairchild, D.; Prakash, P. Microwave ablation at 915 MHz vs 2.45 GHz: A theoretical and experimental investigation. Med. Phys. 2015, 42, 6152–6161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brace, C.L. Microwave tissue ablation: Biophysics, technology, and applications. Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2010, 38, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubner, M.G.; Brace, C.L.; Hinshaw, J.L.; Lee, F.T. Microwave tumor ablation: Mechanism of action, clinical results, and devices. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2010, 21, S192–S203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.N.; Wu, J.X.; He, M.Y.; Cao, M.H.; Lei, J.; Luo, H.L.; Yi, F.M.; Ding, J.L.; Wei, Y.P.; Zhang, W.X. Comparison of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization combined with radiofrequency ablation or microwave ablation for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Hyperth. 2020, 37, 624–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faridi, P.; Keselman, P.; Fallahi, H.; Prakash, P. Experimental assessment of microwave ablation computational modeling with MR thermometry. Med. Phys. 2020, 47, 3777–3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wei, Z.G.; Wang, F.H.; Han, X.Y.; Jia, H.P.; Zhao, D.Y.; Li, C.H.; Liu, L.X.; Yang, X.; Ye, X. Clinical outcomes of percutaneous microwave ablation for pulmonary oligometastases from hepatocellular carcinoma: A retrospective, multicenter study. Cancer Imaging 2024, 24, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.M.; Julien, P.J.; Kaganjo, P.; McKenna, R.J.; Forscher, C.; Natale, R.; Wolfe, R.N.; Butenschoen, K.; Siegel, R.J.; Mirocha, J. Safety and efficacy outcomes from a single-center study of image-guided percutaneous microwave ablation for primary and metastatic lung malignancy. JTO Clin. Res. Rep. 2022, 4, 100454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, C.Q.Y.; Ho, A.; Robinson, H.A.; Huang, L.; Ravindran, P.; Chan, D.L.; Alzahrani, N.; Morris, D.L. A systematic review of microwave ablation for colorectal pulmonary metastases. Anticancer Res. 2023, 43, 2899–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Yan, X.; Zhi, W.; Liu, Y.; Xu, F.; Yan, D. Long-term outcome following microwave ablation of lung metastases from colorectal cancer. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 943715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Páez-Carpio, A.; Gómez, F.M.; Olivé, G.I.; Paredes, P.; Baetens, T.; Carrero, E.; Sánchez, M.; Vollmer, I. Image-guided percutaneous ablation for the treatment of lung nodules: Complications and outcomes. Insights Imaging 2021, 12, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.Z.; Bie, Z.X.; Su, F.; Sun, J.; Li, X.G. Effects of tract embolization on pneumothorax rate after percutaneous pulmonary microwave ablation: A rabbit study. Int. J. Hyperth. 2023, 40, 2165728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.T.C.; Chan, J.W.Y.; Siu, I.C.H.; Lau, R.W.H.; Ng, C.S.H. Safety and feasibility of transbronchial microwave ablation for subpleural lung nodules. Asian Cardiovasc. Thorac. Ann. 2024, 32, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, K.K.W.; Lau, R.W.H.; Baranowski, R.; Krzykowski, J.; Ng, C.S.H. Transbronchial microwave ablation of peripheral lung tumors: The NAVABLATE study. J. Bronchol. Interv. Pulmonol. 2024, 31, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.W.; Su, C.; Li, J.; Yin, N.; Wu, C.P.; Gao, R.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.J.; Lin, Z.Z.; Li, D.X.; et al. The Use of Electromagnetic Navigation Bronchoscopy-Guided Microwave Ablation in Patients with Multiple Bilateral Pulmonary Nodules: A Retrospective Study of 26 Cases. J. Thorac. Dis. 2024, 16, 6347–6356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashour, S.I.; Khan, A.; Song, J.; Chintalapani, G.; Kleinszig, G.; Sabath, B.F.; Lin, J.; Grosu, H.B.; Jimenez, C.A.; Eapen, G.A.; et al. Improving Shape-Sensing Robotic-Assisted Bronchoscopy Outcomes with Mobile Cone-Beam Computed Tomography Guidance. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelghani, R.; Espinoza, D.; Uribe, J.P.; Becnel, D.; Herr, R.; Villalobos, R.; Kheir, F. Cone-Beam Computed Tomography-Guided Shape-Sensing Robotic Bronchoscopy vs. Electromagnetic Navigation Bronchoscopy for Pulmonary Nodules. J. Thorac. Dis. 2024, 16, 5529–5538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, A.T.C.; Chan, J.W.Y.; Siu, I.C.H.; Liu, W.; Lau, R.W.H.; Ng, C.S.H. Robotic-assisted bronchoscopy—Advancing lung cancer management. Front. Surg. 2025, 12, 1566902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leon, H.; Royalty, K.; Mingione, L.; Jaekel, D.; Periyasamy, S.; Wilson, D.; Laeseke, P.; Stoffregen, W.C.; Muench, T.; Matonick, J.P.; et al. Device Safety Assessment of Bronchoscopic Microwave Ablation of Normal Swine Peripheral Lung Using Robotic-Assisted Bronchoscopy. Int. J. Hyperth. 2023, 40, 2187743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, J.; Parrish, R.; Ayasa, L.; Aranguren, P.; Uribe-Buritica, F.L.; Lopez, M.N.; Pineda, C.M.; Cheng, G.; Senitko, M.; Abdelghani, R.; et al. Safety and feasibility of bronchoscopic microwave ablation technology for peripheral lung cancer: A multi-center, prospective, single-arm study protocol. BMC Surg. 2025, 25, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, F.J.; Grand, D.J.; Machan, J.T.; Dipetrillo, T.A.; Mayo-Smith, W.W.; Dupuy, D.E. Microwave Ablation of Lung Malignancies: Effectiveness, CT Findings, and Safety in 50 Patients. Radiology 2008, 247, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarogoulidis, P.; Papadopoulos, V.; Perdikouri, E.I.; Vagionas, A.; Matthaios, D.; Ioannidis, A.; Hohemforst-Schmidt, W.; Huang, H.; Bai, C.; Panagoula, O.; et al. Ablation for Single Pulmonary Nodules, Primary or Metastatic: Endobronchial Ablation Systems or Percutaneous. J. Cancer 2024, 15, 880–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Li, W.; Liu, Y.; Ren, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Zhao, S.; Ye, L.; He, Y.; Zhou, C. The Efficacy and Complications of Computed Tomography Guided Microwave Ablation in Lung Cancer. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2020, 9, 2760–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, J.W.Y.; Lau, R.W.H.; Ngai, J.C.L.; Tsoi, C.; Chu, C.M.; Mok, T.S.K.; Ng, C.S.H. Transbronchial microwave ablation of lung nodules with electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy guidance—A novel technique and initial experience with 30 cases. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2021, 10, 1608–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashiwabara, K.; Fujii, S.; Tsumura, S.; Sakamoto, K.; Semba, H. Efficacy and Safety of Transbronchial Microwave Ablation Therapy under Moderate Sedation in Malignant Central Airway Obstruction Patients with Respiratory Failure: A Single-Institution Retrospective Study. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 147, 2751–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.X.; Fu, X.N.; Yuan, Z.W.; Hu, S.J.; Wang, X.; Ping, W.; Cai, Y.X.; Wang, J.N. Application of Electromagnetic Navigation Bronchoscopy-Guided Microwave Ablation in Multiple Pulmonary Nodules: A Single-Centre Study. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2022, 62, ezac071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.C.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Y.Y.; Wang, J.N.; Hao, Z.P.; Fu, X.N. Improving Outcomes in Electromagnetic Navigation Bronchoscopy-Guided Transbronchial Microwave Ablation for Pulmonary Nodules: The Role of Cone-Beam Computed Tomography. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2025, 19, 17534666251333287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, J.W.Y.; Lau, R.W.H.; Chang, A.T.C.; Siu, I.C.H.; Chu, C.M.; Mok, T.S.K.; Ng, C.S.H. Concomitant electromagnetic navigation transbronchial microwave ablation of multiple lung nodules is safe, time-saving, and cost-effective. JTCVS Tech. 2023, 22, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karir, A.; Shah, P.L.; Orton, C.M. An Insight into Interventional Bronchoscopy. Clin. Med. 2025, 25, 100321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folch, E.; Mittal, A.; Oberg, C. Robotic Bronchoscopy and Future Directions of Interventional Pulmonology. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2022, 28, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, R.M.G.; Ciciena, J.; Almeida, F.A. Robotic-assisted bronchoscopy: A comprehensive review of system functions and analysis of outcome data. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, N.; Ho, E.; Wagh, A.; Murgu, S. Advanced Imaging for Robotic Bronchoscopy: A Review. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Bussy, S.; Chandra, N.C.; Koratala, A.; Lee-Mateus, A.Y.; Barrios-Ruiz, A.; Garza-Salas, A.; Koirala, T.; Funes-Ferrada, R.; Balasubramanian, P.; Patel, N.M.; et al. Robotic-Assisted Bronchoscopy: A Narrative Review of Systems. J. Thorac. Dis. 2024, 16, 5422–5434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, J.S.; Li, W. A Meta-Analysis of Clinical Outcomes After Radiofrequency Ablation and Microwave Ablation for Lung Cancer and Pulmonary Metastases. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2019, 16, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, S.N.; Whitley, J.M.; Thomas, P.A.; Steinke, K. Would You Bet on PET? Evaluation of the Significance of Positive PET Scan Results Post-Microwave Ablation for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 2015, 59, 702–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, J.P.; Barry, C.; Schöder, H.; Camacho, J.C.; Ginsberg, M.S.; Halpenny, D.F. Imaging following Thermal Ablation of Early Lung Cancers: Expected Post-Treatment Findings and Tumour Recurrence. Clin. Radiol. 2021, 76, 864.e13–864.e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castello, A.; Mendogni, P.; Ierardi, A.M.; Zuccotti, G.A.; Luigia, F.; Franzi, S.; Palleschi, A.; Rosso, L.; Carrafiello, G.; Tosi, D.; et al. The role of [18F]FDG PET/CT in pulmonary microwave ablation. J. Nucl. Med. 2024, 65, 242336. [Google Scholar]

- Moradpour, M.; Al-Daoud, O.; Mhana, S.A.A.; Werner, T.; Alavi, A.; Hunt, S. Quantitative 18F-FDG PET/CT for response evaluation after lung ablation for treatment of primary or metastatic lung tumors. J. Nucl. Med. 2024, 65, 241588. [Google Scholar]

- Galluzzi, L.; Guilbaud, E.; Schmidt, D.; Kroemer, G.; Marincola, F.M. Targeting Immunogenic Cell Stress and Death for Cancer Therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2024, 23, 445–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Geng, J.; Zhang, M.H.; Zhou, Y.; Fan, Q.Y.; Chen, J.Y. Treatment of Osteosarcoma with Microwave Thermal Ablation to Induce Immunogenic Cell Death. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 6526–6539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, J.; Ye, X. Potential Biomarkers for Predicting Immune Response and Outcomes in Lung Cancer Patients Undergoing Thermal Ablation. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1268331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaki, H.; Cornelis, F.; Kako, Y.; Kobayashi, K.; Kamikonya, N.; Yamakado, K. Thermal Ablation and Immunomodulation: From Preclinical Experiments to Clinical Trials. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2017, 98, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangamuwa, K.; Leong, T.; Weeden, C.; Asselin-Labat, M.L.; Bozinovski, S.; Christie, M.; John, T.; Antippa, P.; Irving, L.; Steinfort, D. Thermal Ablation in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Review of Treatment Modalities and the Evidence for Combination with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2021, 10, 2842–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| No. of patients | 9 |

| No. of nodules | 11 |

| Patient characteristics | |

| Age (year) | |

| Mean | 68.0 ± 11.0 |

| Range | 50–79 |

| Sex (patients) | |

| Male | 3 (33.3%) |

| Female | 6 (66.7%) |

| Smoke (patients) | |

| Yes | 3 (33.3%) |

| No | 6 (66.7%) |

| Lung nodules characteristics | |

| With biopsy | 11 (100%) |

| Pre-ablation pathological diagnostic yield (%, n/N) | 11 (100%) |

| Histology (nodules) | |

| Primary lung cancer | 3 (27.3%) |

| Metastatic cancer | 8 (72.7%) |

| Location | |

| RUL | 4 (36.3%) |

| RLL | 2 (18.2%) |

| LUL | 2 (18.2%) |

| RML | 3(27.3%) |

| Nodule type | |

| Solid | 7 (63.6%) |

| Mixed | 4 (36.4%) |

| Nodule volume (mm3) | |

| Mean | 1463 ± 1686 |

| Range | 67.0–5027.0 |

| Nodule size (maximum diameter mm) | |

| Mean | 12.1 ± 5.7 |

| Range | 7.0–24.0 |

| EBUS-GS | |

| Concentric | 4 (36.4%) |

| Eccentric | 6 (54.5%) |

| Not visible | 1 (9.1%) |

| Ablation time (minute) | |

| Mean | 10.4 ± 7.1 |

| Range | 1.0–26.0 |

| AE Type, n (%) | Results (n = 9) |

|---|---|

| Throat pain | 22.2% (2/9) |

| Peri-procedural pneumothorax | 0% (0/9) |

| Peri-procedural pneumonia | 11.1% (1/9) |

| Bloody sputum/hemoptysis | 0% (0/9) |

| Shortness of breath | 11.1% (1/9) |

| Chest pain/pleuritic pain | 33.3% (3/9) |

| Tired | 22.2% (2/9) |

| Cough | 22.2% (2/9) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, L.; Miller, R.; Zhao, M.; Lin, G.; Gu, W.; Patel, N.; Van Nostrand, K.; Munoz Pineda, J.A.; Duchman, B.; Tran, B.; et al. Shape-Sensing Robotic-Assisted Bronchoscopic Microwave Ablation for Primary and Metastatic Pulmonary Nodules: Retrospective Case Series. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3248. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243248

Xu L, Miller R, Zhao M, Lin G, Gu W, Patel N, Van Nostrand K, Munoz Pineda JA, Duchman B, Tran B, et al. Shape-Sensing Robotic-Assisted Bronchoscopic Microwave Ablation for Primary and Metastatic Pulmonary Nodules: Retrospective Case Series. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3248. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243248

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Liqin, Russell Miller, Mitchell Zhao, Grace Lin, Wenduo Gu, Niral Patel, Keriann Van Nostrand, Jorge A. Munoz Pineda, Bryce Duchman, Brian Tran, and et al. 2025. "Shape-Sensing Robotic-Assisted Bronchoscopic Microwave Ablation for Primary and Metastatic Pulmonary Nodules: Retrospective Case Series" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3248. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243248

APA StyleXu, L., Miller, R., Zhao, M., Lin, G., Gu, W., Patel, N., Van Nostrand, K., Munoz Pineda, J. A., Duchman, B., Tran, B., & Cheng, G. (2025). Shape-Sensing Robotic-Assisted Bronchoscopic Microwave Ablation for Primary and Metastatic Pulmonary Nodules: Retrospective Case Series. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3248. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243248