The Application and Performance of Artificial Intelligence (AI) Models in the Diagnosis, Classification, and Prediction of Periodontal Diseases: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

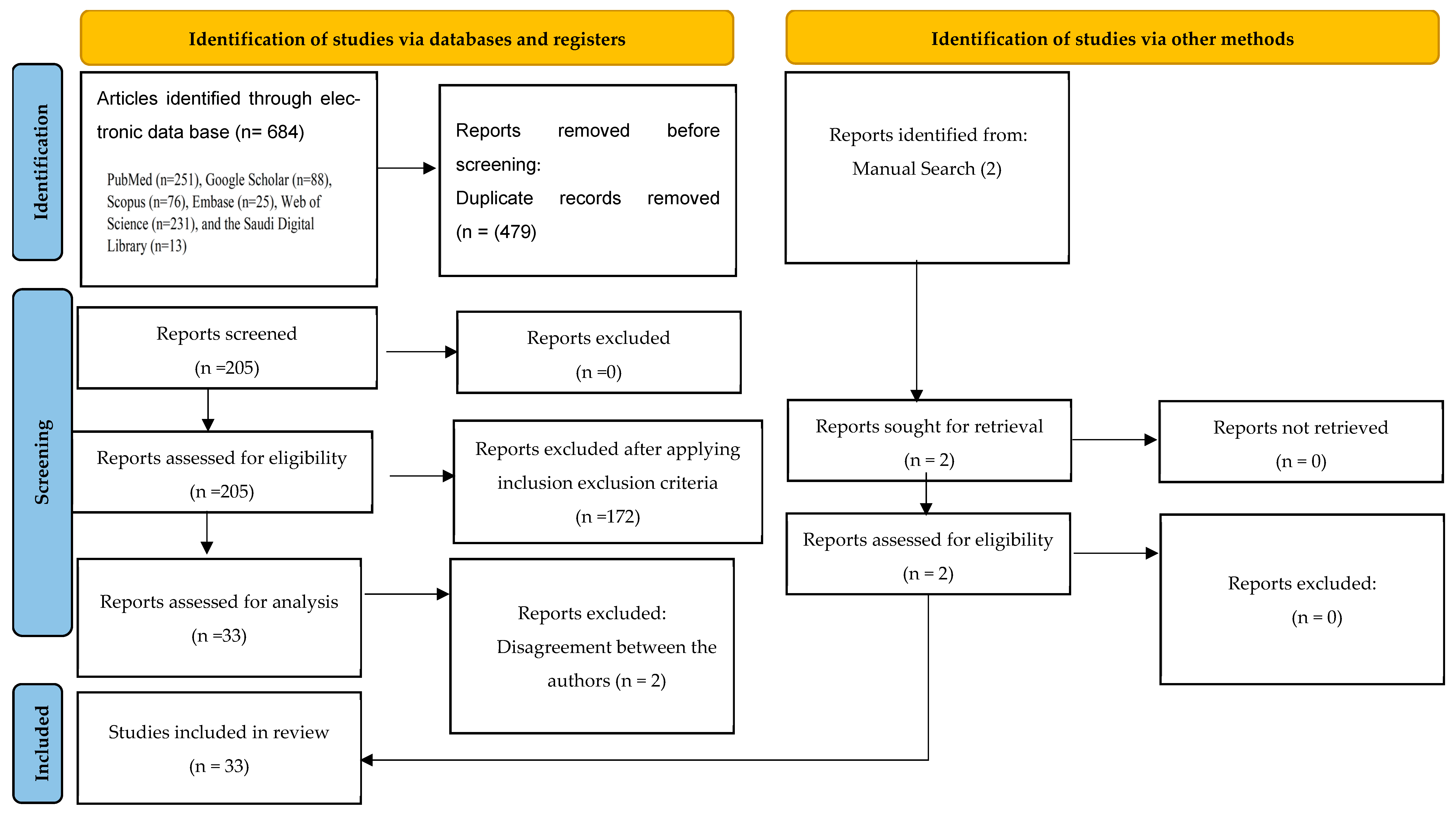

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Extraction of Data

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative Analysis of Included Studies

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Measures of Outcome

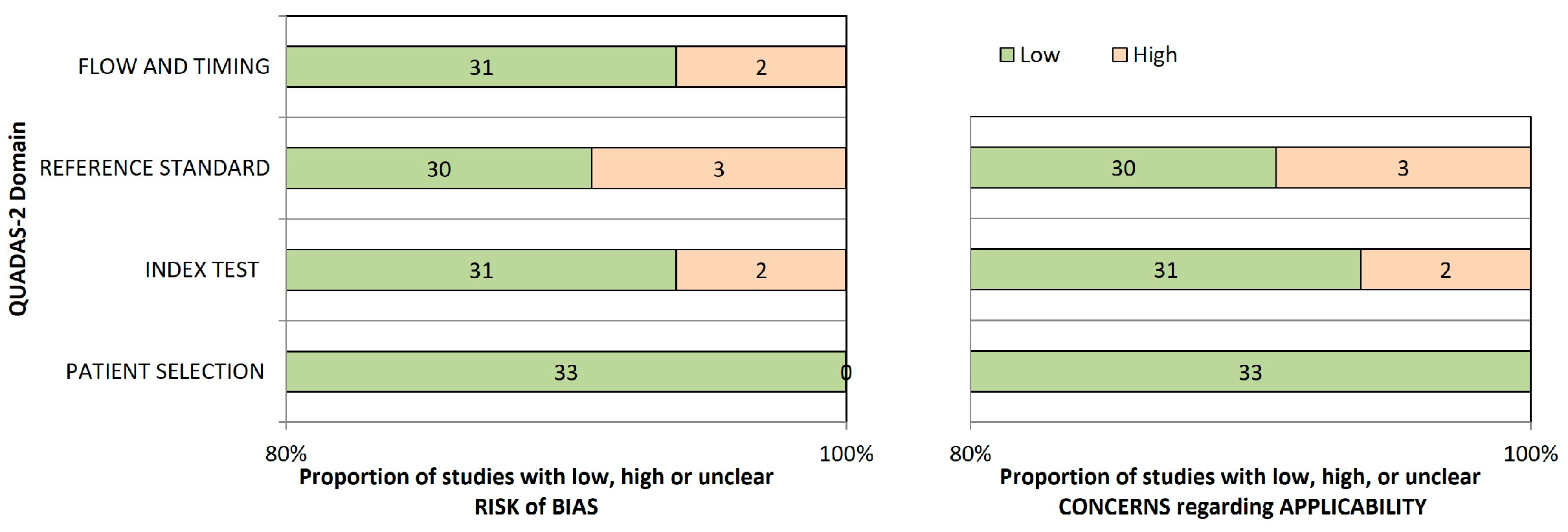

3.4. Risk of Bias Assessment and Applicability Concern

3.5. Assessment of Strength of Evidence

4. Discussion

4.1. Application of AI for Diagnosing, Classifying, and Grading the Severity of Periodontal Diseases

4.2. Application of AI for Diagnosing Gingivitis

4.3. Application of AI to Evaluate Radiographic Alveolar Bone Level and Severity of Alveolar Bone Loss

4.4. Application of AI to the Prediction of Periodontal Diseases

5. Advanced AI Frameworks in Periodontal Diagnostics

5.1. Model Interpretability and Explainability

5.2. Data Imbalance, Bias, and Ethical Considerations

5.3. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scott, J.; Biancardi, A.M.; Jones, O.; Andrew, D. Artificial intelligence in periodontology: A scoping review. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazir, M.A. Prevalence of periodontal disease, its association with systemic diseases and prevention. Int. J. Health Sci. 2017, 11, 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global Oral Health Status Report. Available online: https://www.who.int/team/noncommunicable-diseases/global-status-report-on-oral-health-2022 (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Dubey, P.; Mittal, N. Periodontal diseases-a brief review. Int. J. Oral Health Dent. 2020, 6, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, R.M. Oral health: The silent epidemic. Public Health Rep. 2010, 125, 158–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arigbede, A.O.; Babatope, B.O.; Bamidele, M.K. Periodontitis and systemic diseases: A literature review. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2012, 16, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tattar, R.; da Costa, B.D.; Neves, V.C. The interrelationship between periodontal disease and systemic health: The interrelationship between periodontal disease and systemic health. Br. Dent. J. 2025, 239, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, R.; Eaton, K.A.; Savage, A. Methodological issues in epidemiological studies of periodontitis—How can it be improved? BMC Oral Health 2010, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapple, I.L.C.; Wilson, N.H.F. Manifesto for a paradigm shift: Periodontal health for a better life. Br. Dent. J. 2014, 216, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutinho, R.P.; Coelho, L.; Silva, A.; Pereira, J.; Pinto, M.; Baptista, I. Validation of a dental image-analyzer tool to measure the radiographic defect angle of the intrabony defect in periodontitis patients. J. Periodontal Res. 2012, 47, 695–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhingra, K. Artificial intelligence in dentistry: Current state and future directions. Bull. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2023, 105, 380–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, T.; Tay, F.R.; Gu, L. Application of Artificial Intelligence in Dentistry. J. Dent. Res. 2021, 100, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, M.; Zhu, Y.; Shrestha, A. A Review of Advancements of Artificial Intelligence in Dentistry. Dent. Rev. 2024, 13, 100081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, C.; Shan, Z. Application of Artificial Intelligence in Orthodontics: Current State and Future Perspectives. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asgary, S. Artificial Intelligence in Endodontics: A Scoping Review. Iran. Endod. J. 2024, 19, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khanagar, S.B.; Alfouzan, K.; Awawdeh, M.; Alkadi, L.; Albalawi, F.; Alfadley, A. Application and Performance of Artificial Intelligence Technology in Detection, Diagnosis and Prediction of Dental Caries (DC)-A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1083. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kavyashree, C.; Vimala, H.S.; Shreyas, J. A systematic review of artificial intelligence techniques for oral cancer detection. Healthc. Anal. 2024, 5, 100304. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, E.; Kim, D.; Lee, J.Y.; Park, H.K. Artificial intelligence in detecting temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis on orthopantomogram. Sci. Rep. 2021, 1, 10246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.F.; Siddique, A.; Khan, A.M.; Shetty, B.; Fazal, I. Artificial intelligence in periodontology and implantology—A narrative review. J. Med. Artif. Intell. 2024, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. Br. Med. J. 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, P.F.; Rutjes, A.W.S.; Westwood, M.E.; Mallett, S.; Deeks, J.J.; Reitsma, J.B.; Leeflang, M.M.G.; Sterne, J.A.C.; Bossuyt, P.M.M.; QUADAS-2 Group. QUADAS-2: A Revised Tool for the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossowska, A.; Kusiak, A.; Świetlik, D. Evaluation of the Progression of Periodontitis with the Use of Neural Networks. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanathornwong, B.; Suebnukarn, S. Automatic detection of periodontal compromised teeth in digital panoramic radiographs using faster regional convolutional neural networks. Imaging Sci. Dent. 2020, 50, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozden, F.O.; Ozgonenel, O.; Ozden, B.; Aydogdu, A.H. Diagnosis of periodontal diseases using different classification algorithms: A preliminary study. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2015, 18, 416–421. [Google Scholar]

- Papantonopoulos, G.; Takahashi, K.; Bountis, T.; Loos, B.G. Artificial neural networks for the diagnosis of aggressive periodontitis trained by immunologic parameters. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89757. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, J.; Huang, W.; He, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, R. Construction of artificial neural network diagnostic model and analysis of immune infiltration for periodontitis. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 1041524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhadian, M.; Shokouhi, P.; Torkzaban, P. A decision support system based on support vector machine for diagnosis of periodontal disease. BMC Res. Notes 2020, 13, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chifor, R.; Hotoleanu, M.; Marita, T.; Arsenescu, T.; Socaciu, M.A.; Badea, I.C.; Chifor, I. Automatic segmentation of periodontal tissue ultrasound images with artificial intelligence: A novel method for improving dataset quality. Sensors 2022, 22, 7101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbabi, S.; Jahantigh, F.F.; Moghadam, S.A. Presenting a model for periodontal disease diagnosis using two artificial neural network algorithms. Health Scope 2018, 7, e65330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Jia, X.; Zhan, L.; Fan, X.; Gao, S.; Cai, H.; Huang, X. Tooth Root Surface Area Calculation in Cone-Beam CT via Deep Segmentation. Res. Sq. 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, J.S.; Brandon, R.; Tellez, M.; Albandar, J.M.; Rao, R.; Krois, J.; Wu, H. Developing automated computer algorithms to phenotype periodontal disease diagnoses in electronic dental records. Methods Inf. Med. 2022, 61, e125–e133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shon, H.S.; Kong, V.; Park, J.S.; Jang, W.; Cha, E.J.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, E.Y.; Kang, T.G.; Kim, K.A. Deep learning model for classifying periodontitis stages on dental panoramic radiography. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Icoz, D.; Terzioglu, H.; Ozel, M.A.; Karakurt, R. Evaluation of an artificial intelligence system for the diagnosis of apical periodontitis on digital panoramic images. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2023, 26, 1085–1090. [Google Scholar]

- Alalharith, D.M.; Alharthi, H.M.; Alghamdi, W.M.; Alsenbel, Y.M.; Aslam, N.; Khan, I.U.; Shahin, S.Y.; Dianišková, S.; Alhareky, M.S.; Barouch, K.K. A deep learning-based approach for the detection of early signs of gingivitis in orthodontic patients using faster region-based convolutional neural networks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8447. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Jiang, X.; Sun, W.; Wang, S.H.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.D.; Zhou, W.; Miao, L. Gingivitis identification via multichannel gray-level co-occurrence matrix and particle swarm optimization neural network. Int. J. Imaging Syst. Technol. 2020, 30, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, Y.; Sun, W.; Brown, M.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Miao, L. Expression of Concern: A gingivitis identification method based on contrast-limited adaptive histogram equalization, gray-level co-occurrence matrix, and extreme learning machine. Int. J. Imaging Syst. Technol. 2019, 29, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, C.; He, L.; Miao, L.; Sun, W. A deep learning approach to automatic gingivitis screening based on classification and localization in RGB photos. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt-Bayrakdar, S.; Bayrakdar, İ.Ş.; Yavuz, M.B.; Sali, N.; Çelik, Ö.; Köse, O.; Uzun Saylan, B.C.; Kuleli, B.; Jagtap, R.; Orhan, K. Detection of periodontal bone loss patterns and furcation defects from panoramic radiographs using deep learning algorithm: A retrospective study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.T.; Kabir, T.; Nelson, J.; Sheng, S.; Meng, H.W.; Van Dyke, T.E.; Walji, M.F.; Jiang, X.; Shams, S. Use of the deep learning approach to measure alveolar bone level. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2022, 49, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alotaibi, G.; Awawdeh, M.; Farook, F.F.; Aljohani, M.; Aldhafiri, R.M.; Aldhoayan, M. Artificial intelligence (AI) diagnostic tools: Utilizing a convolutional neural network (CNN) to assess periodontal bone level radiographically—A retrospective study. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.J.; Lee, S.J.; Yong, T.H.; Shin, N.Y.; Jang, B.G.; Kim, J.E. Deep learning hybrid method to automatically diagnose periodontal bone loss and stage periodontitis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, H.S.; Song, I.S.; Jung, K.H. DeNTNet: Deep Neural Transfer Network for the detection of periodontal bone loss using panoramic dental radiographs. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 17615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Chang, M.F.; Angelov, N.; Hsu, C.Y.; Meng, H.W.; Sheng, S.; Glick, A.; Chang, K.; He, Y.R.; Lin, Y.B.; et al. Application of deep machine learning for the radiographic diagnosis of periodontitis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 6629–6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krois, J.; Ekert, T.; Meinhold, L.; Golla, T.; Kharbot, B.; Wittemeier, A.; Dörfer, C.; Schwendicke, F. Deep learning for the radiographic detection of periodontal bone loss. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danks, R.P.; Bano, S.; Orishko, A.; Tan, H.J.; Moreno Sancho, F.; D’Aiuto, F.; Stoyanov, D. Automating Periodontal bone loss measurement via dental landmark localisation. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2021, 16, 1189–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, J.; Yang, S.; Oh, S.H.; Lee, S.P.; Yang, H.J.; Kim, T.I.; Yi, W.J. Automatic and quantitative measurement of alveolar bone level in OCT images using deep learning. Biomed. Opt. Express 2022, 13, 5468–5482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabir, T.; Lee, C.T.; Nelson, J.; Sheng, S.; Meng, H.W.; Chen, L.; Walji, M.F.; Jiang, X.; Shams, S. An end-to-end entangled segmentation and classification convolutional neural network for periodontitis stage grading from periapical radiographic images. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), Houston, TX, USA, 9–12 December 2021; pp. 1370–1375. [Google Scholar]

- 48; Jiang, L.; Chen, D.; Cao, Z.; Wu, F.; Zhu, H.; Zhu, F. A two-stage deep learning architecture for radiographic assessment of periodontal bone loss. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 106. [Google Scholar]

- Uzun Saylan, B.C.; Baydar, O.; Yeşilova, E.; Kurt Bayrakdar, S.; Bilgir, E.; Bayrakdar, İ.Ş.; Çelik, Ö.; Orhan, K. Assessing the Effectiveness of Artificial Intelligence Models for Detecting Alveolar Bone Loss in Periodontal Disease: A Panoramic Radiograph Study. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimpi, N.; McRoy, S.; Zhao, H.; Wu, M.; Acharya, A. Development of a periodontitis risk assessment model for primary care providers in an interdisciplinary setting. Technol. Health Care 2020, 28, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadzyuk, S.; Boliuk, Y.; Luchynskyi, M.; Papinko, I.; Vadzyuk, N. Prediction of the development of periodontal disease. Proc. Shevchenko Sci. Soc. Med. Sci. 2021, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, V.P.; Yansane, A.I.; Brandon, R.G.; Vaderhobli, R.; Lin, G.H.; Hekmatian, H.; Deng, W.; Joshi, N.; Bhandari, H.; Sadat, A.S.; et al. A generative adversarial inpainting network to enhance prediction of periodontal clinical attachment level. J. Dent. 2022, 123, 104211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Q.; She, Y.; Gao, F.; Xu, Y.; Chen, J.; Gao, X. An interpretable computer-aided diagnosis method for periodontitis from panoramic radiographs. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 655556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, D.H.; Jeong, S.N.; Choi, S.H. Diagnosis and prediction of periodontally compromised teeth using a deep learning-based convolutional neural network algorithm. J. Periodontal Implant Sci. 2018, 48, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirmohammadi, A.; Oskouei, S.G. The growing footprint of artificial intelligence in periodontology & implant dentistry. J. Adv. Periodontol. Implant Dent. 2023, 15, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Shastry, K.A.; Shastry, A. An integrated deep learning and natural language processing approach for continuous remote monitoring in digital health. Decis. Anal. J. 2023, 8, 100301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, T.; Himmelstein, D.S.; Beaulieu-Jones, B.K.; Kalinin, A.A.; Do, B.T.; Way, G.P.; Ferrero, E.; Agapow, P.-M.; Zietz, M.; Hoffman, M.M.; et al. Opportunities and obstacles for deep learning in biology and medicine. J. R. Soc. Interface 2018, 15, 20170387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyeena, L.; Yasaswini, P.K.; Nitin Sagar, B.; Mydukuru, A.; Sreeja, K.; Rohith, M. Artificial Intelligence: A neoteric reach in Periodontics. J. Popul. Ther. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 30, 407–414. [Google Scholar]

- Schwendicke, F.; Samek, W.; Krois, J. Artificial intelligence in dentistry: Chances and challenges. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fine, D.H.; Patil, A.G.; Loos, B.G. Classification and diagnosis of aggressive periodontitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, S95–S111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich, T.; Ower, P.; Tank, M.; West, N.X.; Walter, C.; Needleman, I.; Hughes, F.J.; Wadia, R.; Milward, M.R.; Hodge, P.J.; et al. Periodontal diagnosis in the context of the 2017 classification system of periodontal diseases and conditions–implementation in clinical practice. Br. Dent. J. 2019, 226, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graetz, C.; Mann, L.; Krois, J.; Sälzer, S.; Kahl, M.; Springer, C.; Schwendicke, F. Comparison of periodontitis patients’ classification in the 2018 versus 1999 classification. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2019, 46, 908–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papapanou, P.N.; Tonetti, M.S. Diagnosis and epidemiology of periodontal osseous lesions. Periodontology 2000 2000, 22, 8–21. [Google Scholar]

- Neha, F.; Bhati, D.; Shukla, D.K. Retrieval-augmented generation (rag) in healthcare: A comprehensive review. Appl. Inform. 2025, 6, 226. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, P.; Perez, E.; Piktus, A.; Petroni, F.; Karpukhin, V.; Goyal, N.; Küttler, H.; Lewis, M.; Yih, W.T.; Rocktäschel, T.; et al. Retrieval-augmented generation for knowledge-intensive nlp tasks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 9459–9474. [Google Scholar]

- Singhal, K.; Tu, T.; Gottweis, J.; Sayres, R.; Wulczyn, E.; Amin, M.; Hou, L.; Clark, K.; Pfohl, S.R.; Cole-Lewis, H.; et al. Toward expert-level medical question answering with large language models. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, T.; Nayak, A.; Gallo, R.; Rangan, E.; Chen, J.H. Diagnostic reasoning prompts reveal the potential for large language model interpretability in medicine. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision 2017, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 618–626. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. NeurIPS 2017, 30, 4765–4774. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, A.; Otles, E.; Donnelly, J.P.; Krumm, A.; McCullough, J.; DeTroyer-Cooley, O.; Pestrue, J.; Phillips, M.; Konye, J.; Penoza, C.; et al. External validation of a widely implemented proprietary sepsis prediction model in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern. Med. 2021, 181, 1065–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, W.N.; Cohen, I.G. Privacy in the age of medical big data. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Wu, Z.; Xu, X.; Zhan, Y.; Jin, X.; Wang, L.; Qiu, Y. Opportunities and challenges of artificial intelligence in the medical field: Current application, emerging problems, and problem-solving strategies. J. Int. Med. Res. 2021, 49, 3000605211000157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wubineh, B.Z.; Deriba, F.G.; Woldeyohannis, M.M. Exploring the opportunities and challenges of implementing artificial intelligence in healthcare: A systematic literature review. In Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; Volume 42, No. 3, pp. 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Pongtriang, P.; Rakhab, A.; Bian, J.; Guo, Y.; Maitree, K. Challenges in Adopting Artificial Intelligence to Improve Healthcare Systems and Outcomes in Thailand. Health Inf. Res. 2023, 29, 280–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Albis, G.; Forte, M.; Fioriello, M.C.; Artin, A.; Montaruli, A.; Di Grigoli, A.; Kazakova, R.; Dimitrova, M.; Capodiferro, S. Adjunctive Effects of Diode Laser in Surgical Periodontal Therapy: A Narrative Review of the Literature. Oral 2025, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feher, B.; de Souza Oliveira, E.H.; Mendes Duarte, P.; Werdich, A.A.; Giannobile, W.V.; Feres, M. Machine learning-assisted prediction of clinical responses to periodontal treatment. J. Periodontol. 2025, 96, 1199–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Research question | How well do AI-based models predict, classify, and diagnose periodontal diseases? |

| Population | Patients who underwent investigation for periodontal diseases, including those assessed using radiographs (periapical, bitewing, panoramic), intraoral images, and periodontal clinical examination. |

| Intervention | AI models designed for the diagnosis, classification, and prediction of periodontal diseases. |

| Comparison | Expert/specialist opinions and reference standards/models. |

| Outcome | Diagnostic, classification, and predictive performance metrics of AI models were predefined and grouped as follows: (1) Diagnostic performance—accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, recall, precision, F1 measure, Positive Predictive Value (PPV), Negative Predictive Value (NPV), and statistical significance; (2) Discrimination performance—Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (ROC), Area Under the Curve (AUC), Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (AUROC), mean average precision (mAP), and precision–recall curve (PRC); (3) Image basis metrics—Intersection over Union (IoU), Dice similarity coefficient (DSC), and mean absolute error (MAE); (4) Reliability/agreement measure—Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC); (5) Clinical output measures—radiographic alveolar bone level (RBL) and alveolar bone loss (ABL). |

| Table 2a. Application of AI for Diagnosing, Classifying, and Grading the Severity of Periodontal Diseases | |||||||||||||

| Sl No. | Authors | Year of Publication | Study Design | Algorithm Architecture | Objective of the Study | No. of Patients/Images/Photographs for Testing | Primary Objective | Modality | Comparison, If Any | Evaluation Accuracy/Average Accuracy/Statistical Significance | Results: (+) Effective, (−) Noneffective, (N) Neutral | Outcomes | Author Suggestions/Conclusions |

| 1 | Ossowska A et al. [22] | 2022 | Retrospective study | ANN | To assess grades of periodontitis based on severity | 110 patients: training group: 90 persons; test group: 20 persons. | Severity of periodontitis | Datasets | Training and test group comparison | Sensitivity = 85.7% Specificity = 80.0% Percentage of correctly classified patients = 84.2% for the training set | (+) Effective | ANNs were used correctly to classify patients according to the grade of periodontitis | ANNs may be useful tools in everyday dental practice to assess the risk of periodontitis development. |

| 2 | Thanathornwong B et al. [23] | 2020 | Retrospective study | Faster R CNN | To identify periodontally compromised teeth | 100 digital panoramic radiographs | Detection of periodontally compromised teeth | DPRs | Three experienced periodontists | Precision = 81% Recall = 80% Sensitivity = 84% Specificity = 88% F measure = 81% | (+) Effective | Faster R-CNN trained on a limited number of labeled imaging data had satisfactory detection ability of periodontally compromised health | Application of Faster R-CNNs may reduce diagnostic effort by saving assessment time and enabling automated screening documentation. |

| 3 | Ozden F O et al. [24] | 2015 | Retrospective study | SVM DT ANN | To develop an identification unit for classifying periodontal diseases | 150 patients divided into two groups [training (100) and testing (50)] | Classification of periodontal diseases | Datasets | Experienced periodontist | Performances of SVM and DT = 98% Performance of ANN = 46% Total computational times of SVM and DT: 19.91 and 7.00 s | (+) Effective | DT and SVM were the best to classify the periodontal diseases. The ANN had the worst correlation between input and output variables. | A unique system for diagnosing periodontal diseases may be possible. |

| 4 | Papantonopoulos G et al. [25] | 2014 | Retrospective study | MLP ANNs | To classify patients into aggressive periodontitis (AP) or chronic periodontitis (CP) | a. First study (29 patients) b. Second study (76 patients) c. Third study (80 patients) | Classification of periodontitis | Datasets | Canonical discriminant analysis and binary logistic regression | ANNs gave 90–98% accuracy in classifying patients as having either AgP or CP | (+) Effective | ANNs can be employed for the accurate diagnosis of Ag P or CP. | ANNs allow clinicians to better adapt specific treatment protocols for their AgP and CP patients. |

| 5 | Xiang J et al. [26] | 2022 | Observational study | Random forest algorithm and ANN | To construct a diagnostic model for periodontitis | Two datasets containing (64 and 183) and (69 and 241) periodontitis samples | Diagnosis of periodontitis | Gene expression data | Not mentioned | AUC = 0.945; ROC = 0.900 | (+) Effective | The authors successfully identified key biomarkers of periodontitis using machine learning and developed a satisfactory diagnostic model. | The model provides a valuable reference for the prevention and early detection of periodontitis. |

| 6 | Farhadian M et al. [27] | 2020 | Cross-sectional study | ANN | To automate diagnoses of various periodontal diseases | 300 patients: 160: gingivitis; 60: localized periodontitis; 80: generalized periodontitis] | Diagnosis of periodontal disease | Datasets | Not mentioned | Overall correct classification accuracy of 88.7%; overall hypervolume under the manifold value of 0.912; and has the best performance | (+) Effective | The designed classification model has an acceptable performance in predicting periodontitis. | This system will help less experienced dentists and young residents in making decisions for the diagnosis of periodontal disease. |

| 7 | Chifor R et al. [28] | 2022 | Observational study | Mask R CNN and U-Net | To identify anatomical elements for periodontal diagnosis | 3417 periodontal U.S. images to form the datasets for training | Diagnosis of periodontitis | Ultrasound images | Low-experience operator (young dentist) | IOU is 10% for the periodontal pocket and 75.6% for gingiva | (+) Effective | Mask R-CNN had overall better results in the automatic segmentation of periodontal tissue in ultrasound images, compared with U-NET. | A method like this may help a less experienced operator to generate higher-quality datasets in the future. |

| 8 | Arbabi S et al. [29] | 2018 | Retrospective study | LM SCG | To evaluate the role of ANNs in periodontal disease diagnosis | 190 periodontal disease cases [training: 160; testing: 30] | Diagnosis of periodontitis | Datasets | Comparison between two algorithms | LM algorithm’s training in 22 performances gained 0.0098, and the SCG algorithm’s training in 33 performances had 0.055 for the MSE | (+) Effective | The LM algorithm with fewer iterations and a minimum MSE had a better performance than that of the SCG algorithm. | ANNs can be used as an effective tool. |

| 9 | Su S et al. [30] | 2022 | Observational study | Mask R-CNN | To develop a computer-assisted system based on a CNN to segment and calculate the root surface area on CBCT | 24 teeth from 20 patients; CBCT images were recorded | Diagnosis of periodontitis | CBCT images | Medical image control system (Mimics) | Mean RSA difference between two groups was −0.20 ± 5.1 mm Alveolar bone mAP = 0.848 ± 0.004; mIOU = 0.715 ± 0.004 | (+) Effective | The CNN is an automatic, efficient, standardized, and accurate method to calculate the RSA. | The CNN can help dental professionals attain more targeted subsequent clinical or radiographic diagnostics and treatment on CBCT. |

| 10 | Patel JS et al. [31] | 2022 | Retrospective study | PeriodDx diagnoser and PerioDx extractor | To phenotype periodontal disease diagnoses from different sections | 27,138 data points of patients | Diagnosis of periodontal disease | Electronic dental records | Two domain experts | The PerioDx diagnoser performed with 96% precision, 98% recall, and 97% of the F-1 measure. Similarly, the PerioDx extractor performed with 91% precision, 87% recall, and 95% of the F-1 measure to automatically extract patients’ PD diagnoses. | (+) Effective | Successfully developed, tested, and deployed two automated algorithms on big EDR datasets to improve the completeness of PD diagnoses with 100% completeness. | This approach is recommended for use in other large databases for the evaluation of their EDR data quality and for phenotyping PD diagnoses and other relevant variables. |

| 11 | Shon, H.S. et al. [32] | 2022 | Retrospective study | U-Net and YOLOv5 | To classify periodontitis stages of each individual tooth using dental panoramic radiographs | 1044 images | Classification of periodontitis | DPRs | Dental specialist | The integrated framework had an accuracy of 92.9%, with a recall and precision of 80.7% and 72.4%, respectively, on average, across all four stages. | (+) Effective | The novel framework was shown to exhibit a relatively high level of performance. | A systematic application will be developed in the future to provide ancillary data for diagnosis and basic data for the treatment and prevention of periodontal disease. |

| 12 | İçöz D et al. [33] | 2023 | Observational study | DL models YOLOv3 Darknet model | To evaluate the effectiveness of an artificial intelligence (AI) system in the detection of roots with apical periodontitis (AP) | 306 DPRs | Diagnosis of periodontitis | DPRs | Two oral and maxillofacial radiologists | Recall = 98% Precision = 56% F-1 measure = 71% | (+) Effective | The DL method developed for the automatic detection of AP showed high recall, precision, and F-1 measure values for the mandible but low values for the maxilla. | The performance of YOLO can be improved by dimensionally classifying the lesions and by including a sufficient and equal number of training and testing data on the basis of each tooth group. |

| Table 2b: Application of AI to diagnose gingivitis | |||||||||||||

| Sl No. | Authors | Year of publication | Study Design | Algorithm Architecture | Objective of the study | No. of Patients/Images/Photographs for Testing | Primary Objective | Modality | Comparison, If Any | Evaluation Accuracy/Average Accuracy/Statistical Significance | Results: (+) Effective, (−) Noneffective, (N) neutral | Outcomes | Author Suggestions/Conclusions |

| 1 | Alalharith D.M et al. [34] | 2020 | Retrospective study | Two faster region-based CNN models using ResNet-50 CNN | To detect and diagnose early signs of gingivitis | 134 intraoral images (107 for training and 27 for testing) | Diagnosis of gingivitis | Intraoral image dataset | Expert dentists | Inflammation detection model: Accuracy = 77.12% Precision = 88.02% Recall = 41.75% mAP = 68.19% | (+) Effective | This study proved the viability of deep learning models for the detection and diagnosis of gingivitis in intraoral images. | This model can be used in the field of dentistry and aid in reducing the severity of periodontal disease globally through pre-emptive, non-invasive diagnosis. |

| 2 | Li W et al. [35] | 2020 | Dataset | MGLCM + PSONN) | To automate diagnosis of chronic gingivitis | 400 gingivitis and 400 healthy images were acquired to build the training dataset | Diagnosis of gingivitis | Oral images | State-of-the-art approaches | Specificity: 78.1% Sensitivity: 78.2% Precision: 78.2% Accuracy = 78.2% F1 score = 78.1% of MGLCM (PSONN as a classifier) method | (+) Effective | The model is an efficient and accurate method. | Provides new ideas with the application of AI technology to diagnose periodontal disease and help dentists with laborious tasks. |

| 3 | Li W et al. [36] | 2019 | Dataset | CLAHE + GLCM + ELM | To automate diagnosis of chronic gingivitis | 93 images; 58 gingivitis and 35 healthy images | Diagnosis of gingivitis | Oral images | Conventional methods | Sensitivity, specificity, precision, and accuracy of our method are 75%, 73%, 74%, and 74%, respectively. | (+) Effective | The models were more accurate and sensitive than state-of-the-art approaches. | The combination of CLAHE, GLCM, and ELM is an efficient and accurate method to classify tooth types and diagnose gingivitis. |

| 4 | Li W et al. [37] | 2021 | Retrospective study | CNN model | To automate screening of gingivitis, dental calculus, and soft deposits | Out of 625 patients, 3932 oral photos were captured [training, validation, and testing subsets] | Diagnosis of gingivitis | Oral photos | Three board-certified dentists | AUC for detecting gingivitis, dental calculus, and soft deposits were 87.11%, 80.11%, and 78.57%, respectively. | (+) Effective | The model significantly outperformed on both classification and localization tasks, which indicates the effectiveness of multitask learning on dental disease detection. | The model could be meaningful for promoting public dental health. |

| Table 2c: Application of AI to evaluate radiographic alveolar bone level and severity of alveolar bone loss | |||||||||||||

| Sl No. | Authors | Year of Publication | Study Design | Algorithm Architecture | Objective of the Study | No. of Patients/Images/Photographs for Testing | Primary Objective | Modality | Comparison, If Any | Evaluation Accuracy/Average Accuracy/Statistical Significance | Results: (+) Effective, (−) Noneffective, (N) Neutral | Outcomes | Author Suggestions/Conclusions |

| 1 | Kurt-Bayrakdar S et al. [38] | 2024 | Retrospective study | CNN | To examine the performance of this algorithm in the detection of periodontal bone losses and bone loss patterns | 1121 DPRs: training set (80%), validation set (10%), and testing set (10%) | Assessment of alveolar bone loss | DPRs | Three periodontists and one oral maxillofacial radiologist | ABL Sensitivity = 100% Precision = 99.5% F1 score = 99.7% Accuracy = 99.4% AUC = 95.1% Furcation defects Sensitivity = 89.2% Precision = 93.3% F1 score = 91.2% Accuracy = 83.7% AUC = 0.868 | (+) Effective | The system showed the highest diagnostic performance in the detection of total alveolar bone losses and the lowest in the detection of vertical bone losses. | AI systems offer promising results in determining periodontal bone loss patterns and furcation defects from dental radiographs. |

| 2 | Lee C T et al. [39] | 2022 | Retrospective study | Deep CNN (DL-based CAD models) | To measure RBL to aid diagnosis | 693 periapical radiographs (original dataset); 644 additional periapical images [RBL] (additional dataset) | Assessment of alveolar bone level | Intraoral digital radiographs | Independent examiners (periodontist and periodontal resident) | DSC for segmentation: over 0.91. Accuracy = 85% | (+) Effective | The proposed DL model provides reliable RBL measurements and image-based periodontal diagnosis. | This model has to be further optimized and validated by a larger number of images to facilitate its application. |

| 3 | Alotaibi G et al. [40] | 2022 | Retrospective study | Combination of deep CNN (VGG-16) and self-trained network | To detect and evaluate severity of bone loss due to periodontal disease | 1724 periapical radiographs from 1610 adult patients [70% training, 20% validation, and 10% testing datasets] | Assessment of alveolar bone loss | Intraoral periapical images/radiographs | Three independent examiners, including a periodontist | Diagnostic accuracy for classifying normal versus disease was 73% and 59% for classification of the levels of severity of the bone loss. Precision, recall, and F1 scores for the binary classifier were above 70%. | (+) Effective | The deep CNN (VGG-16) was useful to detect alveolar bone loss as well as to detect the severity of bone loss in teeth. | A computer-aided detection system should be able to aid in the detection and staging of periodontitis. |

| 4 | Chang HJ et al. [41] | 2020 | Observational study | [Hybrid framework] Combined CNN (Mask R-CNN) and conventional CAD approach | To automatically detect and classify the periodontal bone loss of each individual tooth | 330, 115, and 73 panoramic radiographs (90% training set and 10% test set) | Assessment of alveolar bone loss | DPRs | Radiologists (professor, fellow, and residents) | Pearson correlation = 0.73, and the intraclass correlation value = 0.91 overall for the whole jaw | (+) Effective | The novel hybrid framework demonstrated high accuracy and excellent reliability in the automatic diagnosis of periodontal bone loss and the staging of periodontitis. | The framework may substantially improve dental professionals’ performance with regard to the diagnosis and treatment of periodontitis. |

| 5 | Kim J et al. [42] | 2019 | Retrospective study | Deep CNN (DeNTNet) | To detect PBL with teeth numbering | 12,179 panoramic dental radiographs [11, 189 (trained), 190 (validated), and 800 (tested)] | Assessment of alveolar bone loss | DPRs | Experienced dental hygienists with 5, 9, 16, 17, and 19 years of practice | When compared to dental clinicians F1 score of 0.75 on the test set, the average performance of dental clinicians was 0.69 | (+) Effective | This proposed model was able to achieve a PBL detection performance superior to that of dental clinicians. | This approach substantially benefits clinical practice by improving the efficiency of diagnosing PBL and reducing the workload involved. |

| 6 | Chang J et al. [43] | 2022 | Retrospective study | Multitasking Inception V3 model (deep machine learning) | To test the accuracy of radiographic bone loss (RBL) classification | 236 patients with 1836 periapical radiographs | Assessment of alveolar bone loss | Periapical digital radiographs | Three calibrated periodontists | Accuracy = 87% Sensitivity = 86% Specificity = 88% PPV = 88% NPV = 86% | (+) Effective | Application of deep machine learning for the detection of alveolar bone loss yielded promising results. | Higher accuracy of RBL classification can be achieved with more clinical data and proper model construction for valuable clinical application by machine learning. |

| 7 | Krois J et al. [44] | 2019 | Observational study | Deep CNN | To detect PBL on panoramic scans | 85 randomly chosen radiographs | Assessment of alveolar bone loss | DPRs | Six experienced dentists | CNN Accuracy = 81% Sensitivity = 81% Specificity = 81% Dentist Accuracy = 76% Sensitivity = 92% Specificity = 63% | (+) Effective | A moderately complex trained CNN showed at least a similar diagnostic performance to that of experienced dentists. | Dentists’ diagnostic efforts when using radiographs may be reduced by applying machine learning-based technologies. |

| 8 | Danks RP et al. [45] | 2021 | Retrospective study | Deep neural network with hourglass architecture | To determine the disease severity stage and regressive percentage of PBL | 340 fully anonymized periapical radiographs | Classification of periodontitis and assessment of PBL | Periapical radiographs | Postgraduate specialist trainees | The landmark localization achieved percentage correct key points of 88.9%, 73.9%, and 74.4%, respectively, and a combined PCK of 83.3%. When compared, the average PBL error was 10.69%, with a severity stage accuracy of 58%. | (+) Effective | The system showed the promising ability to localize landmarks and estimate periodontal bone loss. | Future work is required so that a computer-assisted radiographic assessment system can provide significant support in periodontitis and interventional application. |

| 9 | Kim SH et al. [46] | 2022 | Observational study | CNN models (U-Net, Dense-UNet, and U2-Net) | To measure quantitatively and automatically the alveolar bone level by detecting the CEJ junction and alveolar bone crest | 500 images were scanned manually [400 images for training, 50 images for validation, and 50 images for testing] | Assessment of alveolar bone level | OCT images; optical coherence tomography | One periodontist with seven years of experience | All CNN models showed MAEs of less than 0.25 mm in the x and y coordinates and greater than 90% successful detection rates at 0.5 mm for both the ABC and CEJ | (+) Effective | The CNN models showed high segmentation accuracies in the tooth enamel and alveolar bone regions, as well as high correlation and reliability with ABL. | The proposed method has the potential to be utilized in periodontitis diagnosis or other clinical periodontal procedures. |

| 10 | Kabir T et al. [47] | 2021 | Observational study | Deep learning network HYNETS | To evaluate HYNETS in grading periodontitis and RBL assessment | 700 X-rays were divided into training, testing, and validation sets | Assessment of alveolar bone loss | Periapical radiographic images | Periodontists (board-certified clinical and board-certified professor) and resident | HYNETS achieved average Dice coefficients of 0.96 and 0.94 for the bone area and tooth segmentation and an average AUC of 0.97 for periodontitis stage assignment. | (+) Effective | HYNETS could potentially transform clinical diagnosis from a manual, time-consuming, and error-prone task to efficient and automated periodontitis stage assignment. | HYNETS could be useful in the future for integration and will be successful in clinical practice. |

| 11 | Jiang L et al. [48] | 2022 | Retrospective study | Deep learning [U-Net and YOLO v4] | To establish a comprehensive and accurate radiographic staging of PBL | 640 panoramic images | Assessment of alveolar bone loss | Panoramic images | Three experienced periodontal physicians | The overall classification accuracy of the model was 77%. | (+) Effective | The model classification was more accurate than that of general practitioners in detecting and classifying alveolar bone loss. | The model could assist dentists in the comprehensive and accurate assessment of PBL. |

| 12 | Uzun Saylan BC et al. [49] | 2023 | Observational study | PyTorch-based YOLO-v5 model | To evaluate the success of AI models used in the detection of radiographic alveolar bone loss | 685 panoramic radiographs (80% training 10% validation, and 10% testing) | Assessment of alveolar bone level | DPRs | Oral and maxillofacial radiologist and periodontologist with at least 10 years of experience | ABL Sensitivity = 75% Precision = 76% F1 score = 76% | (+) Effective | The lowest sensitivity and F1 score values were associated with total alveolar bone loss, while the highest values were observed in the maxillary incisor region. | The study shows that artificial intelligence has high potential in analytical studies evaluating periodontal bone loss situations. |

| Table 2d: Application of AI to predict periodontal diseases | |||||||||||||

| Sl No. | Authors | Year of Publication | Study Design | Algorithm Architecture | Objective of the Study | No. of Patients/Images/Photographs for Testing | Primary Objective | Modality | Comparison, If Any | Evaluation Accuracy/Average Accuracy/Statistical Significance | Results: (+) Effective, (−) Noneffective, (N) Neutral | Outcomes | Author Suggestions/Conclusions |

| 1 | Shimpi N et al. [50] | 2020 | Cohort study | ANN DT | To propose and test a new PD risk assessment model | 11,048 (4766 positive and 6282 controls) | Prediction of periodontal risk | Datasets | NB LR SVM | DT showed a sensitivity of 87.08% and a specificity of 93.5%; DT and ANN demonstrated higher accuracy in classifying patients with high or low PD risk as compared to NB, LR, and SVM. | (+) Effective | ML methods would be effective when applied to improving patient care through the early detection of PD or to new preventive approaches to PD by assisting healthcare professionals to evaluate patients’ PD risk. | Evaluation of performances of these algorithms in other populations is essential to demonstrate their generalizability and relevance and utility as clinical decision support tools in the medical setting. |

| 2 | Vadzyuk S et al. [51] | 2021 | Cross-sectional study | Neural networks | To predict the development of periodontal disease | 156 students [84 people with periodontal disease and 72 without periodontal pathology (control)] | Prediction of periodontal disease | Datasets | Conventional methods and expert opinions | The diagnostic sensitivity of the first prognostic model was 83.33%, and the specificity was 92.31%. The second model was characterized by 90.00% sensitivity and 78.57% specificity. | (+) Effective | The psychophysiological features can be effective predictors of the development of pathologies and periodontal tissues including inflammation. | The method of modeling using neural networks can effectively predict the risk of periodontal disease development in young people. |

| 3 | Kearney VP et al. [52] | 2022 | Retrospective study | Inpainting network | To enhance the CAL prediction accuracy | 80,326 images were used for training, 12,901 for validation, and 10,687 to compare CALs | Prediction of periodontal disease | Bitewing and periapical radiographs | Experienced academic practicing clinicians (certified periodontist, 11 years of experience, and two dentists, 22 and 38 years of experience) | Comparator p-values demonstrated statistically significant improvement in CAL prediction with MAEs of 1.04 mm and 1.50 mm. | (+) Effective | The use of a generative adversarial inpainting network with partial convolutions to predict CALs from bitewing and periapical images is superior. | Artificial intelligence was developed and utilized to predict clinical attachment levels compared to clinical measurements. |

| 4 | Li H et al. [53] | 2021 | Retrospective study | Mask R-CNN (deetal-Perio) | To predict the severity of periodontitis | First data: 302 digitized panoramic radiographs; second data: 204 panoramic radiographs | Prediction of severity of periodontitis | DPRs | Expert dentist with more than 10 years of experience | First dataset: Macro F1 score = 0.894 Accuracy = 89.6%, Second dataset: Macro F1 score = 0.820 Accuracy = 82.4% | (+) Effective | This system outperformed state-of-the-art methods and showed robustness on two datasets in periodontitis prediction. | Deetal-Perio is a suitable method for periodontitis screening and diagnostics. |

| 5 | Lee JH et al. [54] | 2018 | Retrospective study | deep CNN | To develop and evaluate the accuracy of the model for the diagnosis and prediction of PCT | 1740 periapical radiographic images into training dataset (1044), validation dataset (348), and datasets (348) for molars and premolars | Diagnosis and prediction of periodontitis | Periapical radiographs | Three calibrated periodontists | Diagnostic accuracy for PCT was 81% for premolars and 76.7% for molars. Accuracy of prediction extraction for premolars was 82.8% and an AUC of 82.6% for deep CNN models. | (+) Effective | The deep CNN algorithm had higher diagnostic accuracy for identifying PCT among premolars than among molars. They had similar diagnostic and predictive accuracies to those obtained by periodontists with respect to the prediction of extraction. | The system is expected to become an effective and efficient method for diagnosing and predicting PCT. |

| Outcome | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Risk of Bias | Publication Bias | Strength of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Application of AI for diagnosing, classifying, and grading the severity of periodontal diseases [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33] | Not Present | Not Present | Not Present | Present | Not Present | ⨁⨁⨁◯ |

| Application of AI to diagnose gingivitis [34,35,36,37] | Not Present | Not Present | Not Present | Present | Not Present | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ |

| Application of AI to evaluate radiographic alveolar bone level and severity of alveolar bone loss [38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49] | Not Present | Not Present | Not Present | Not Present | Not Present | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ |

| Application of AI to predict periodontal diseases [50,51,52,53,54] | Not Present | Not Present | Not Present | Present | Not Present | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jafer, M.; Ibraheem, W.; Dawood, T.; Abbas, A.; Hakami, K.; Khurayzi, T.; Hakami, A.J.; Alqahtani, S.; Aldosari, M.; Ageely, K.; et al. The Application and Performance of Artificial Intelligence (AI) Models in the Diagnosis, Classification, and Prediction of Periodontal Diseases: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3247. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243247

Jafer M, Ibraheem W, Dawood T, Abbas A, Hakami K, Khurayzi T, Hakami AJ, Alqahtani S, Aldosari M, Ageely K, et al. The Application and Performance of Artificial Intelligence (AI) Models in the Diagnosis, Classification, and Prediction of Periodontal Diseases: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3247. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243247

Chicago/Turabian StyleJafer, Mohammed, Wael Ibraheem, Tazeen Dawood, Ali Abbas, Khalid Hakami, Turki Khurayzi, Abdullah J. Hakami, Shahd Alqahtani, Mubarak Aldosari, Khaled Ageely, and et al. 2025. "The Application and Performance of Artificial Intelligence (AI) Models in the Diagnosis, Classification, and Prediction of Periodontal Diseases: A Systematic Review" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3247. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243247

APA StyleJafer, M., Ibraheem, W., Dawood, T., Abbas, A., Hakami, K., Khurayzi, T., Hakami, A. J., Alqahtani, S., Aldosari, M., Ageely, K., Khanagar, S. B., Vishwanathaiah, S., & Maganur, P. C. (2025). The Application and Performance of Artificial Intelligence (AI) Models in the Diagnosis, Classification, and Prediction of Periodontal Diseases: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3247. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243247