Acute Ischemic Stroke in Non-Arteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy

Abstract

1. Introduction

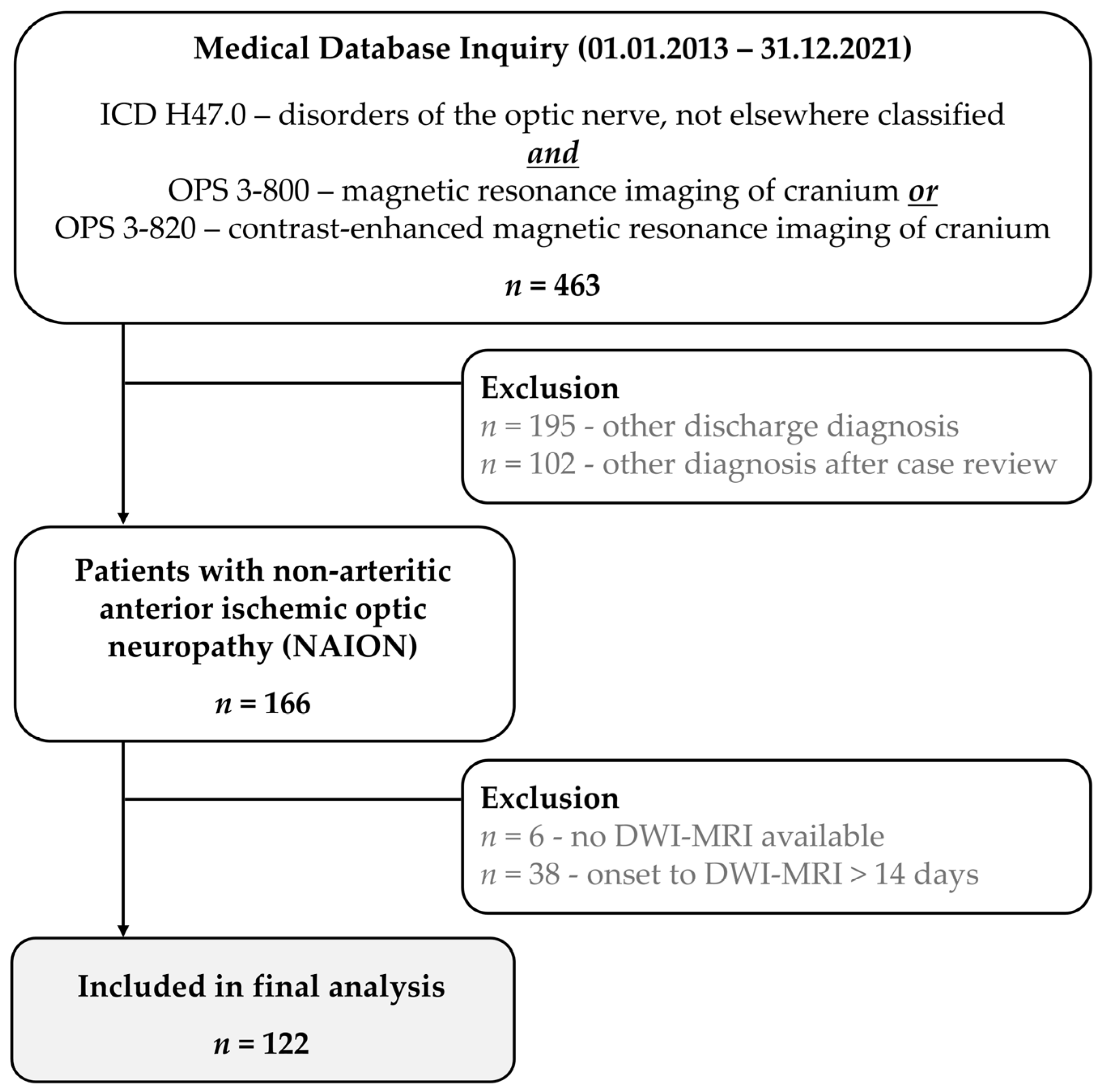

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection and Data Extraction

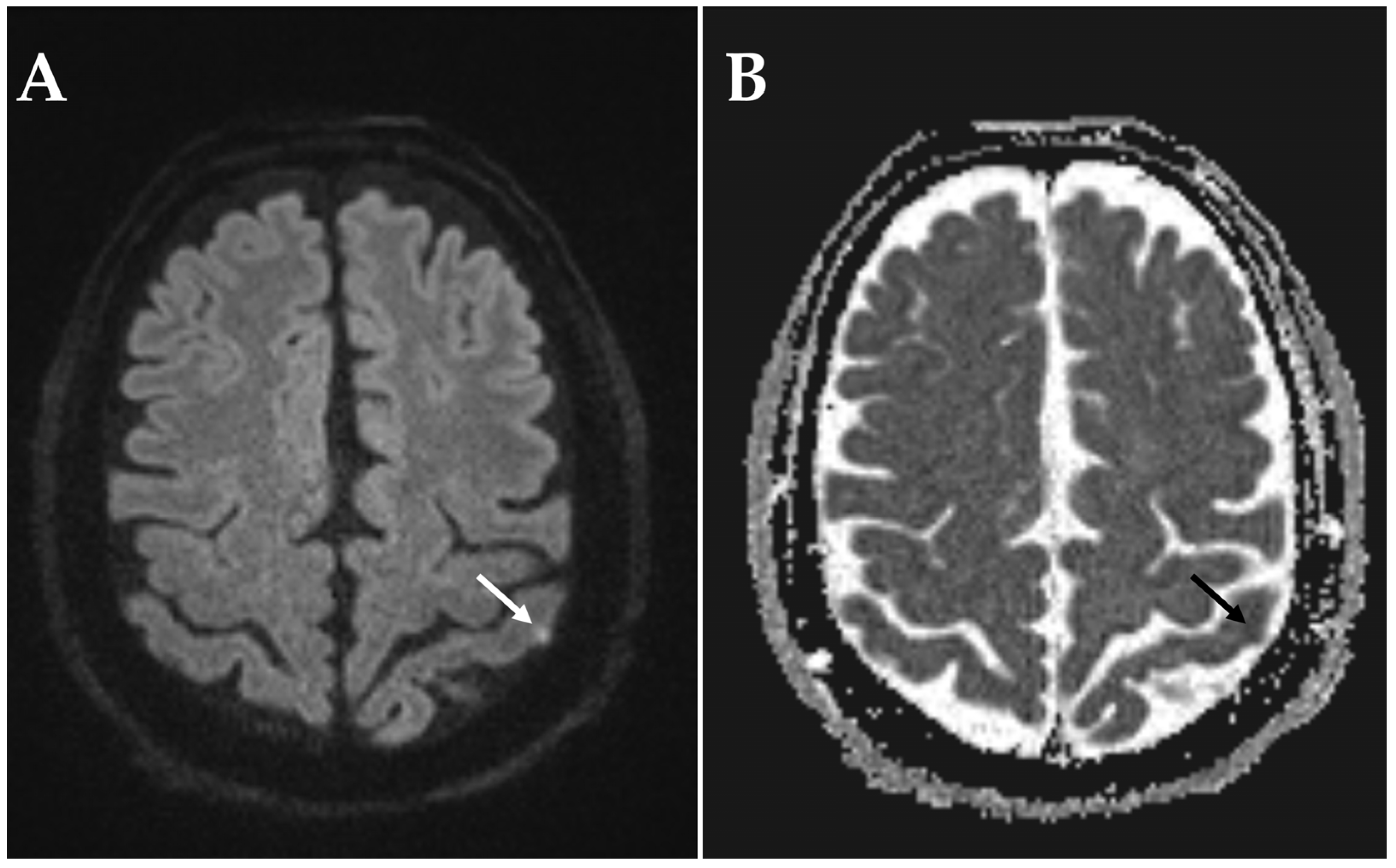

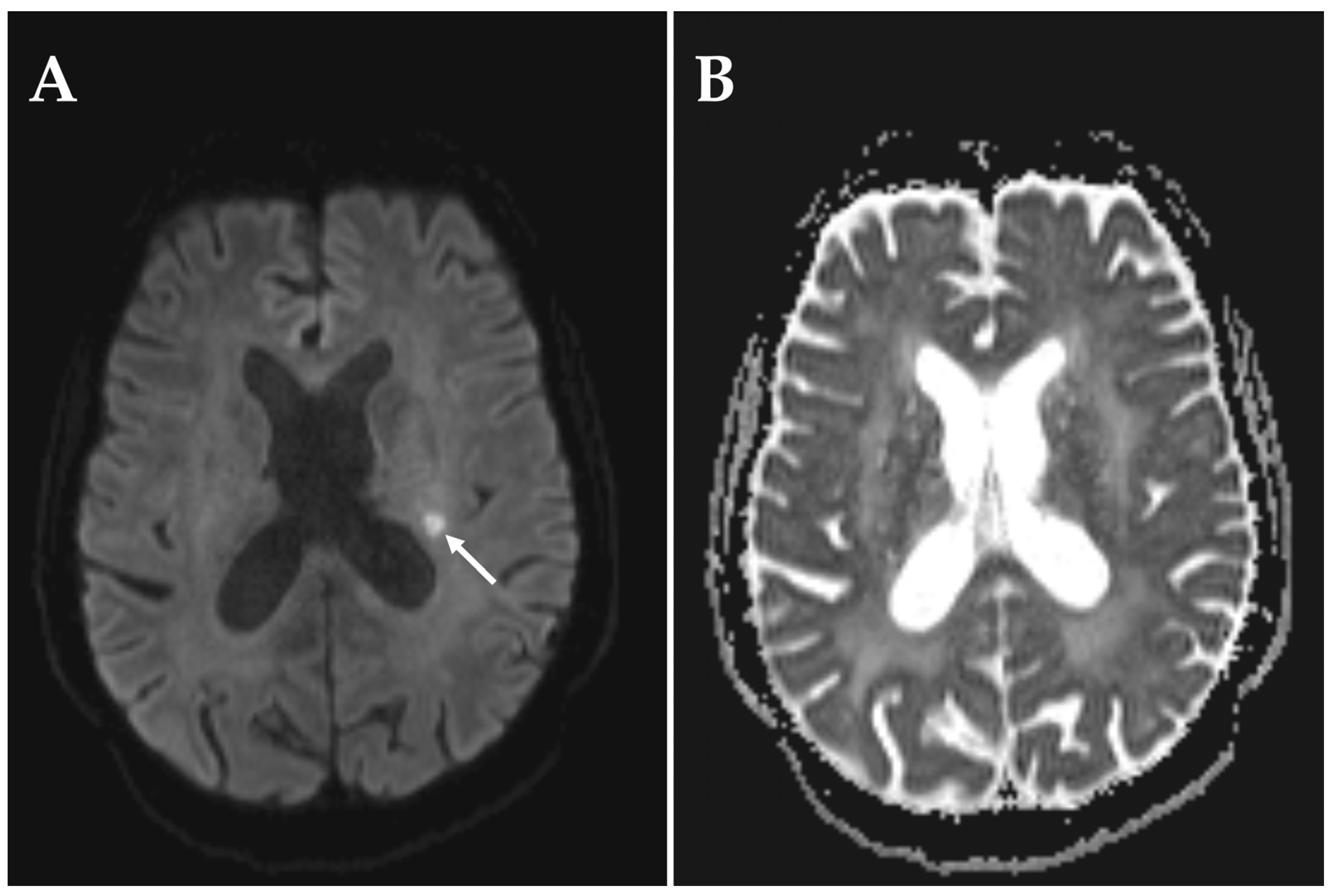

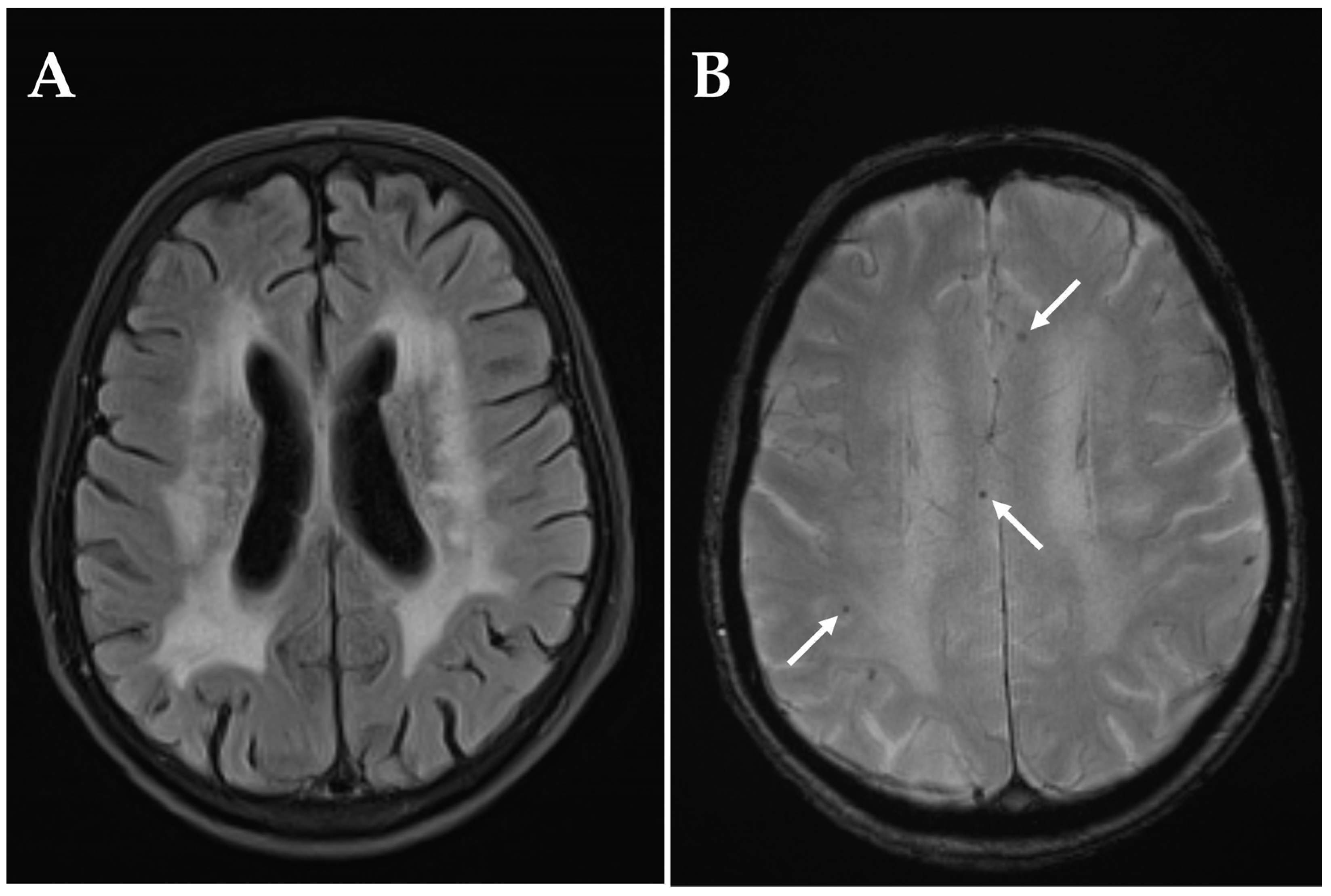

2.2. Imaging Acquisition and Analysis

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ION | Ischemic optic neuropathies |

| AION | Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy |

| PION | Posterior ischemic optic neuropathy |

| NAION | Non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy |

| A-AION | Arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy |

| RAPD | Relative afferent pupillary defect |

| ONDS | Optic nerve sheath decompression |

| DWI-MRI | Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging |

| ADC | Apparent diffusion coefficient |

| ICD | International Classification of Diseases |

| OPS | Operation and Procedure Classification System |

| FLAIR | Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery |

References

- Hayreh, S.S. Ischaemic optic neuropathy. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2000, 48, 171–194. [Google Scholar]

- Hayreh, S.S. Ischemic optic neuropathy. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2009, 28, 34–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayreh, S.S. Ischemic optic neuropathies-where are we now? Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2013, 251, 1873–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biousse, V.; Newman, N.J. Ischemic Optic Neuropathies. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2428–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvetat, M.L.; Pellegrini, F.; Spadea, L.; Salati, C.; Zeppieri, M. Non-Arteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy (NA-AION): A Comprehensive Overview. Vision 2023, 7, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayreh, S.S. Posterior ischaemic optic neuropathy: Clinical features, pathogenesis, and management. Eye 2004, 18, 1188–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Park, K.A.; Oh, S.Y. Prevalence and incidence of non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy in South Korea: A nationwide population-based study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 102, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hattenhauer, M.G.; Leavitt, J.A.; Hodge, D.O.; Grill, R.; Gray, D.T. Incidence of nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1997, 123, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, L.N.; Arnold, A.C. Incidence of nonarteritic and arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Population-based study in the state of Missouri and Los Angeles County, California. J. Neuroophthalmol. 1994, 14, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, R.C.; Bhatti, M.T.; Crum, O.M.; Lesser, E.R.; Hodge, D.O.; Chen, J.J. Reexamining the Incidence of Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy: A Rochester Epidemiology Project Study. J. Neuroophthalmol. 2024, 44, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preechawat, P.; Bruce, B.B.; Newman, N.J.; Biousse, V. Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy in patients younger than 50 years. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 144, 953–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, A.C.; Costa, R.M.; Dumitrascu, O.M. The spectrum of optic disc ischemia in patients younger than 50 years (an Amercian Ophthalmological Society thesis). Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc. 2013, 111, 93–118. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Yu, Y.; Liu, W.; Deng, T.; Xiang, D. Risk Factors for Non-arteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy: A Large Scale Meta-Analysis. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 618353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonagel, F.; Wilhelm, H.; Birk, M.; Kelbsch, C. Individual Prognosis and Clinical Course of Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy. J. Neuroophthalmol. 2025; Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialer, O.Y.; Stiebel-Kalish, H. Evaluation and management of nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy: A national survey. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2024, 262, 3323–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilares-Morgado, R.; Nunes, H.M.M.; Dos Reis, R.S.; Barbosa-Breda, J. Management of ocular arterial ischemic diseases: A review. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2023, 261, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badla, O.; Badla, B.A.; Almobayed, A.; Mendoza, C.; Kishor, K.; Bhattacharya, S.K. Ischemic Optic Neuropathy: A Review of Current and Potential Future Pharmacotherapies. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parthasarathi, P.; Moss, H.E. Review of evidence for treatments of acute non arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Eye 2024, 38, 2267–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, R.W.; Hayreh, S.S.; Podhajsky, P.A.; Tan, E.S.; Moke, P.S. Aspirin therapy in nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1997, 123, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botelho, P.J.; Johnson, L.N.; Arnold, A.C. The effect of aspirin on the visual outcome of nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1996, 121, 450–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, R.; Singh, D.; Sharma, M.; James, M.; Sharma, P.; Menon, V. Steroids versus No Steroids in Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 1623–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakravan, M.; Sanjari, N.; Esfandiari, H.; Pakravan, P.; Yaseri, M. The effect of high-dose steroids, and normobaric oxygen therapy, on recent onset non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy: A randomized clinical trial. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2016, 254, 2043–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, N.J.; Dickersin, K.; Kaufman, D.; Kelman, S.; Scherer, R.; Ischemic Optic Neuropathy Decompression Trial Study Group. Characteristics of patients with nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy eligible for the Ischemic Optic Neuropathy Decompression Trial. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1996, 114, 1366–1374. [Google Scholar]

- Dickersin, K.; Everett, D.; Feldon, S.; Ischemic Optic Neuropathy Decompression Trial Study Group. Optic nerve decompression surgery for nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION) is not effective and may be harmful. JAMA 1995, 273, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modarres, M.; Sanjari, M.S.; Falavarjani, K.G. Vitrectomy and release of presumed epipapillary vitreous traction for treatment of nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy associated with partial posterior vitreous detachment. Ophthalmology 2007, 114, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soheilian, M.; Koochek, A.; Yazdani, S.; Peyman, G.A. Transvitreal optic neurotomy for nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Retina 2003, 23, 692–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, A.C.; Hepler, R.S.; Lieber, M.; Alexander, J.M. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1996, 122, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simsek, T.; Eryilmaz, T.; Acaroglu, G. Efficacy of levodopa and carbidopa on visual function in patients with non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2005, 59, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portnoy, S.L.; Beer, P.M.; Packer, A.J.; Van Dyk, H.J. Embolic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. J. Clin. Neuroophthalmol. 1989, 9, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman, M.F.; Shahi, A.; Green, W.R. Embolic ischemic optic neuropathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1978, 86, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomsak, R.L. Ischemic optic neuropathy associated with retinal embolism. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1985, 99, 590–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Dong, M.; Han, M. Multiple Retinal Emboli in Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy. Ophthalmology, 2025; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Kosmorsky, G.; Straga, J.; Knight, C.; Dagirmanjian, A.; Davis, D.A. The role of transcranial Doppler in nonarteritic ischemic optic neuropathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1998, 126, 288–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, Y.Y.; Ho, C.H.; Chen, Y.C.; Kuo, S.C. Stroke Risk Following Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2444534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shemesh, R.; Rosenblatt, H.N.; Huna-Baron, R.; Klein, A.; Zloto, O.; Levy, N. The Risk of Ischemic Stroke in Patients With Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy: A Big Data Study. J. Neuroophthalmol. 2025; Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Singh, G.; Madike, R.; Cugati, S. Central retinal artery occlusion: A stroke of the eye. Eye 2024, 38, 2319–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, S.W.; Lee, S.C.; Kwon, O.W.; Kim, Y.D.; Byeon, S.H. Co-occurrence of acute retinal artery occlusion and acute ischemic stroke: Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging study. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 157, 1231–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helenius, J.; Arsava, E.M.; Goldstein, J.N.; Cestari, D.M.; Buonanno, F.S.; Rosen, B.R.; Ay, H. Concurrent acute brain infarcts in patients with monocular visual loss. Ann. Neurol. 2012, 72, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golsari, A.; Bittersohl, D.; Cheng, B.; Griem, P.; Beck, C.; Hassenstein, A.; Nedelmann, M.; Magnus, T.; Fiehler, J.; Gerloff, C.; et al. Silent Brain Infarctions and Leukoaraiosis in Patients with Retinal Ischemia: A Prospective Single-Center Observational Study. Stroke 2017, 48, 1392–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danyel, L.A.; Miszczuk, M.; Connolly, F.; Villringer, K.; Bohner, G.; Rossel-Zemkouo, M.; Siebert, E. Time Course and Clinical Correlates of Retinal Diffusion Restrictions in Acute Central Retinal Artery Occlusion. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2021, 42, 1661–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danyel, L.A.; Miszczuk, M.; Villringer, K.; Bohner, G.; Siebert, E. Retinal diffusion restrictions in acute branch retinal arteriolar occlusion. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozsunar, Y.; Sorensen, A.G. Diffusion- and perfusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in human acute ischemic stroke: Technical considerations. Top Magn. Reason. Imaging 2000, 11, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budde, M.D.; Skinner, N.P. Diffusion MRI in acute nervous system injury. J. Magn. Reason. 2018, 292, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponte, C.; Grayson, P.C.; Robson, J.C.; Suppiah, R.; Gribbons, K.B.; Judge, A.; Craven, A.; Khalid, S.; Hutchings, A.; Watts, R.A.; et al. DCVAS Study Group. 2022 American college of rheumatology/eular classification criteria for giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022, 74, 1881–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysidis, S.; Duftner, C.; Dejaco, C.; Schäfer, V.S.; Ramiro, S.; Carrara, G.; Scirè, C.A.; Hocevar, A.; Diamantopoulos, A.P.; Iagnocco, A.; et al. Definitions and reliability assessment of elementary ultrasound lesions in giant cell arteritis: A study from the OMERACT Large Vessel Vasculitis Ultrasound Working Group. RMD Open 2018, 4, e000598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Kim, M.S.; Jeong, H.Y.; Cho, K.H.; Oh, S.W.; Byun, S.J.; Woo, S.J.; Yang, H.K.; Hwang, J.M.; Park, K.H.; Kim, C.K.; et al. Nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy is associated with cerebral small vessel disease. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, R.C.; Bhatti, M.T.; Crum, O.M.; Lesser, E.R.; Hodge, D.O.; Klaas, J.P.; Chen, J.J. Stroke Rate, Subtype, and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy: A Population-Based Study. J. Neuroophthalmol. 2020, 40, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.; Okaj, I.; Scott, J.; Atwal, S.; Stark, C.; Tahir, R.; Khalidi, N.; Junek, M. Intracranial GCA: A comprehensive systematic review. Rheumatology 2025, 64, 4517–4524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, A.; Güngör, İ. 24-Hour Blood Pressure Patterns in NAION: Exploring the Impact of Dipping Classifications and Comorbidities. Neuroophthalmology 2025, 49, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaillard-Groleas, C.; Ormezzano, O.; Pollet-Villard, F.; Vignal, C.; Gohier, P.; Thuret, G.; Rougier, M.B.; Pepin, J.L.; Chiquet, C. Study of nycthemeral variations in blood pressure in patients with non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 34, 1576–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hathaway, J.T.; Shah, M.P.; Hathaway, D.B.; Zekavat, S.M.; Krasniqi, D.; Gittinger, J.W.; Cestari, D.; Mallery, R.; Abbasi, B.; Bouffard, M.; et al. Risk of Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy in Patients Prescribed Semaglutide. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2024, 142, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, A.Y.; Kuo, H.T.; Wang, Y.H.; Lin, C.J.; Shao, Y.C.; Chiang, C.C.; Hsia, N.Y.; Lai, C.T.; Tseng, H.; Wu, B.Q.; et al. Semaglutide and Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy Risk Among Patients With Diabetes. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2025, 143, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Mohan, S.; Wu, L. GLP-1 receptor agonists and non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy: What an endocrinologist needs to know. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2025; dgaf541, Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalela, J.A.; Kidwell, C.S.; Nentwich, L.M.; Luby, M.; Butman, J.A.; Demchuk, A.M.; Hill, M.D.; Patronas, N.; Latour, L.; Warach, S. Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography in emergency assessment of patients with suspected acute stroke: A prospective comparison. Lancet 2007, 369, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiebach, J.B.; Schellinger, P.D.; Jansen, O.; Meyer, M.; Wilde, P.; Bender, J.; Schramm, P.; Jüttler, E.; Oehler, J.; Hartmann, M.; et al. CT and diffusion-weighted MR imaging in randomized order: Diffusion-weighted imaging results in higher accuracy and lower interrater variability in the diagnosis of hyperacute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2002, 33, 2206–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.S.; Chung, P.W.; Kim, Y.B.; Moon, H.S.; Suh, B.C.; Yoon, W.T.; Yoon, K.J.; Lee, Y.T.; Won, Y.S.; Park, K.Y. Small deep infarction in patients with atrial fibrillation: Evidence of lacunar pathogenesis. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2013, 36, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harazeen, A.; Memon, M.Z.; Frade, H.; Chhabra, A.; Chaudhry, U.; Shaltoni, H. Infarcts of a Cardioembolic Source Mimicking Lacunar Infarcts: Case Series With Clinical and Radiological Correlation. Cureus 2023, 15, e43665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, R.A.; Kamel, H.; Granger, C.B.; Piccini, J.P.; Katz, J.M.; Sethi, P.P.; Pouliot, E.; Franco, N.; Ziegler, P.D.; Schwamm, L.H.; et al. Atrial Fibrillation In Patients With Stroke Attributed to Large- or Small-Vessel Disease: 3-Year Results From the STROKE AF Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol. 2023, 80, 1277–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Visual Acuity |

|---|---|

| No vision impairment | ≥6/12 (≤0.30 logMAR) |

| Mild vision impairment | <6/12–≥6/18 (>0.30–≤0.48 logMAR) |

| Moderate vision impairment | <6/18–≥6/60 (>0.48–≤1.00 logMAR) |

| Severe vision impairment | <6/60–≥3/60 (>1.00–≤1.30 logMAR) |

| Blindness | <3/60 (>1.30 logMAR) |

| Demographic Information | NAION Cohort (n = 122) |

|---|---|

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 64.6 ± 11.9 |

| Female (n, %) | 44 (36.1) |

| Ophthalmological features | |

| NAION left eye (n, %) | 73 (59.8) |

| NAION right eye (n, %) | 47 (38.5) |

| Bilateral NAION (n, %) | 2 (1.6) |

| Onset | |

| Sudden (n, %) | 63 (51.6) |

| Gradual (n, %) | 15 (12.3) |

| Upon awakening (n, %) | 17 (13.9) |

| Not reported (n, %) | 27 (22.1) |

| Visual Impairment * | |

| Quantitative decimal visual acuity (mean ± SD) | 0.4 ± 0.3 |

| Quantitative logMAR visual acuity (mean ± SD) | 0.40 ± 0.52 |

| No vision impairment (n, %) | 58 (46.8) |

| Mild (n, %) | 7 (5.6) |

| Moderate (n, %) | 30 (24.2) |

| Severe (n, %) | 19 (15.3) |

| Blind (n, %) | 10 (8.1) |

| RAPD | |

| Present on affected eye (n, %) | 62 (50.8) |

| Not present (n, %) | 30 (24.6) |

| Present in other eye (n, %) | 11 (9.0) |

| Pharmacological mydriasis (n, %) | 17 (13.9) |

| Not reported (n, %) | 2 (1.6) |

| Classification Criteria for Giant Cell Arteritis | NAION Cohort (n = 122) |

|---|---|

| Morning stiffness shoulders/arms, neck/torso (n, %) | 0/23 (0) |

| Jaw or tongue claudication (n, %) | 0/77 (0) |

| New temporal headache (n, %) | 8/91 (8.8) |

| Scalp tenderness (n, %) | 1/34 (2.9) |

| Abnormality of the A. temporalis superficialis (n, %) | 1/42 (2.4) |

| ESR > 50 mm/h (n, %) | 7/73 (11.3) |

| ESR (mm/h, mean ± SD) ˠ | 18.3 ± 16.7 |

| C-reactive protein > 10 mg/l (n, %) | 14/120 (11.7) |

| C-reactive protein (mg/l, mean ± SD) ˣ | 8.9 ± 35.3 |

| “Halo-sign” present (n, %) | 0/66 (0) |

| Temporal artery biopsy positive (n, %) | 0/11 (0) |

| Radiological evidence of large-vessel vasculitis | 0/0 (0) |

| Total (n = 122) | Early DWI-MRI Day 0–6 (n = 63) ˠ | Late DWI-MRI Day 7–14 (n = 59) ˣ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Field strength (Tesla) | |||

| 1.5 (n, %) | 67 (54.9) | 29 (46.0) | 38 (64.4) |

| 3.0 (n, %) | 55 (45.1) | 34 (54.0) | 21 (35.6) |

| Slice thickness (mm) | |||

| 1.5 (n, %) | 2 (1.6) | 1 (1.6) | 1 (1.7) |

| 2.0 (n, %) | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 1 (1.7) |

| 2.5 (n, %) | 32 (26.2) | 19 (30.2) | 13 (22.0) |

| 3.0 (n, %) | 80 (65.6) | 40 (63.5) | 40 (67.8) |

| 5.0 (n, %) | 6 (4.9) | 2 (3.2) | 4 (6.8) |

| 6.0 (n, %) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.6) | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wenzel, V.; Danyel, L.A.; Meidinger, S.; Siebert, E.; Knoche, T.; Pietrock, C. Acute Ischemic Stroke in Non-Arteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3192. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243192

Wenzel V, Danyel LA, Meidinger S, Siebert E, Knoche T, Pietrock C. Acute Ischemic Stroke in Non-Arteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3192. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243192

Chicago/Turabian StyleWenzel, Victor, Leon Alexander Danyel, Sophia Meidinger, Eberhard Siebert, Theresia Knoche, and Charlotte Pietrock. 2025. "Acute Ischemic Stroke in Non-Arteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3192. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243192

APA StyleWenzel, V., Danyel, L. A., Meidinger, S., Siebert, E., Knoche, T., & Pietrock, C. (2025). Acute Ischemic Stroke in Non-Arteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3192. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243192