Executive Functions and Subjective Cognitive Decline: The Moderating Role of Depressive Symptoms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Participants

2.4. Measurements

- conceptualization/similarities—the subject is required to identify abstract links between objects from the same semantic category.

- phonemic verbal fluency—the subject generates as many words as possible within one minute that begin with a specified letter (e.g., “S”).

- motor programming—the subject is required to perform Luria’s “fist–edge–palm” sequence correctly six consecutive times.

- conflicting instructions—the subject gives the opposite response to the examiner’s alternating signals (e.g., If I tap twice, you tap once. If I tap once, you tap twice).

- go/no-go task—the subject again produces opposite responses but must now differentiate between two distinct response types (e.g., I tap once, you tap once. If I tap twice, you do not tap).

- environmental autonomy/prehension—the subject demonstrates the ability to inhibit automatic grasping when the examiner touches both of their palms.

- The FAB shows good psychometric characteristics, with an internal consistency of Cronbach’s α = 0.78, indicating a satisfactory degree of cohesion among the six subtests [41]. Each item is scored 0–3, with the raw total ranging from 0–18. Scores were adjusted for age and education to obtain equivalent scores. Lower adjusted scores indicate greater frontal/executive dysfunction. According to Italian norms, intact performance corresponds to an adjusted score ≥12.02.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Profile

3.2. Neuropsychological and Psychological Performance

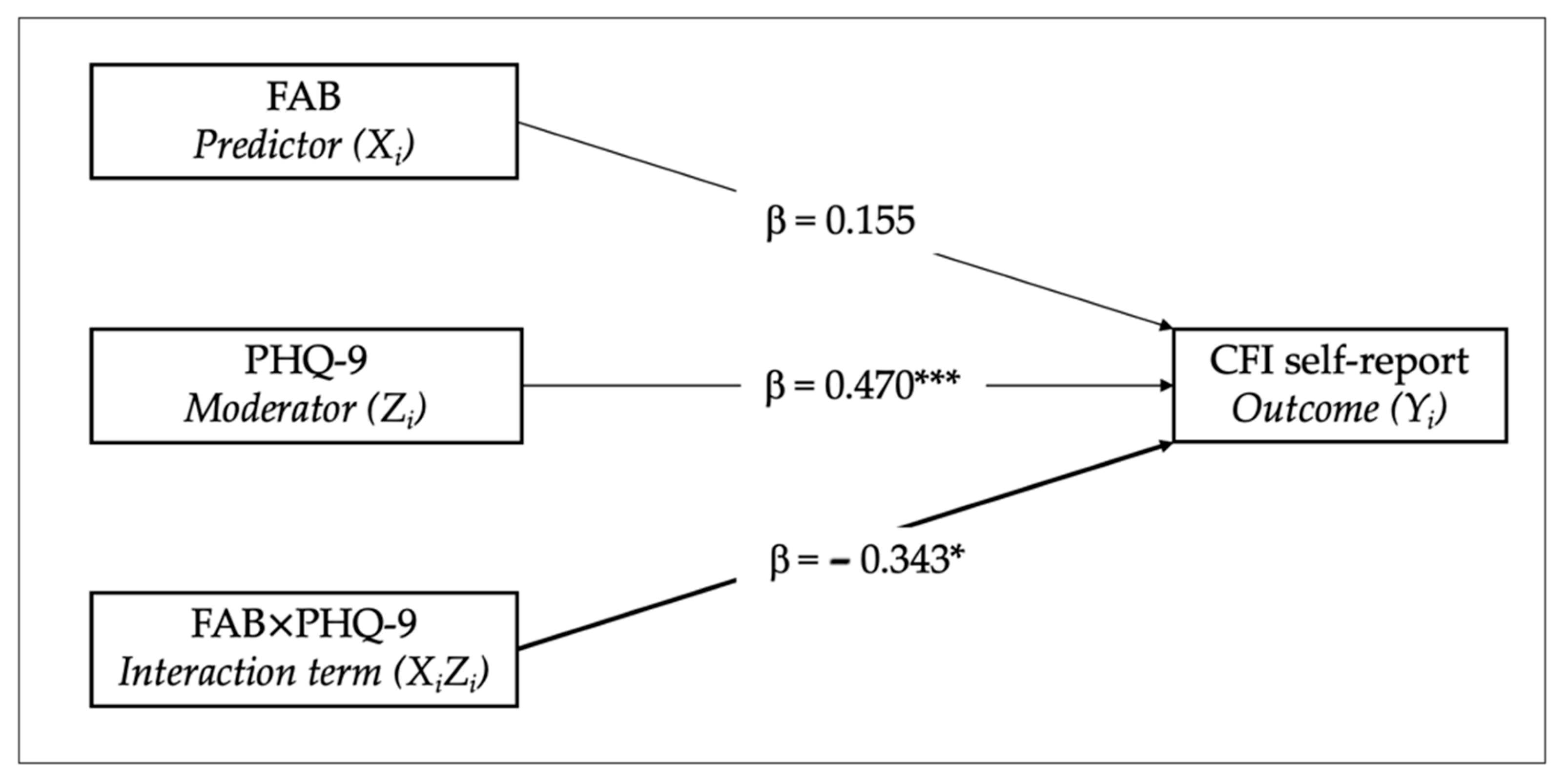

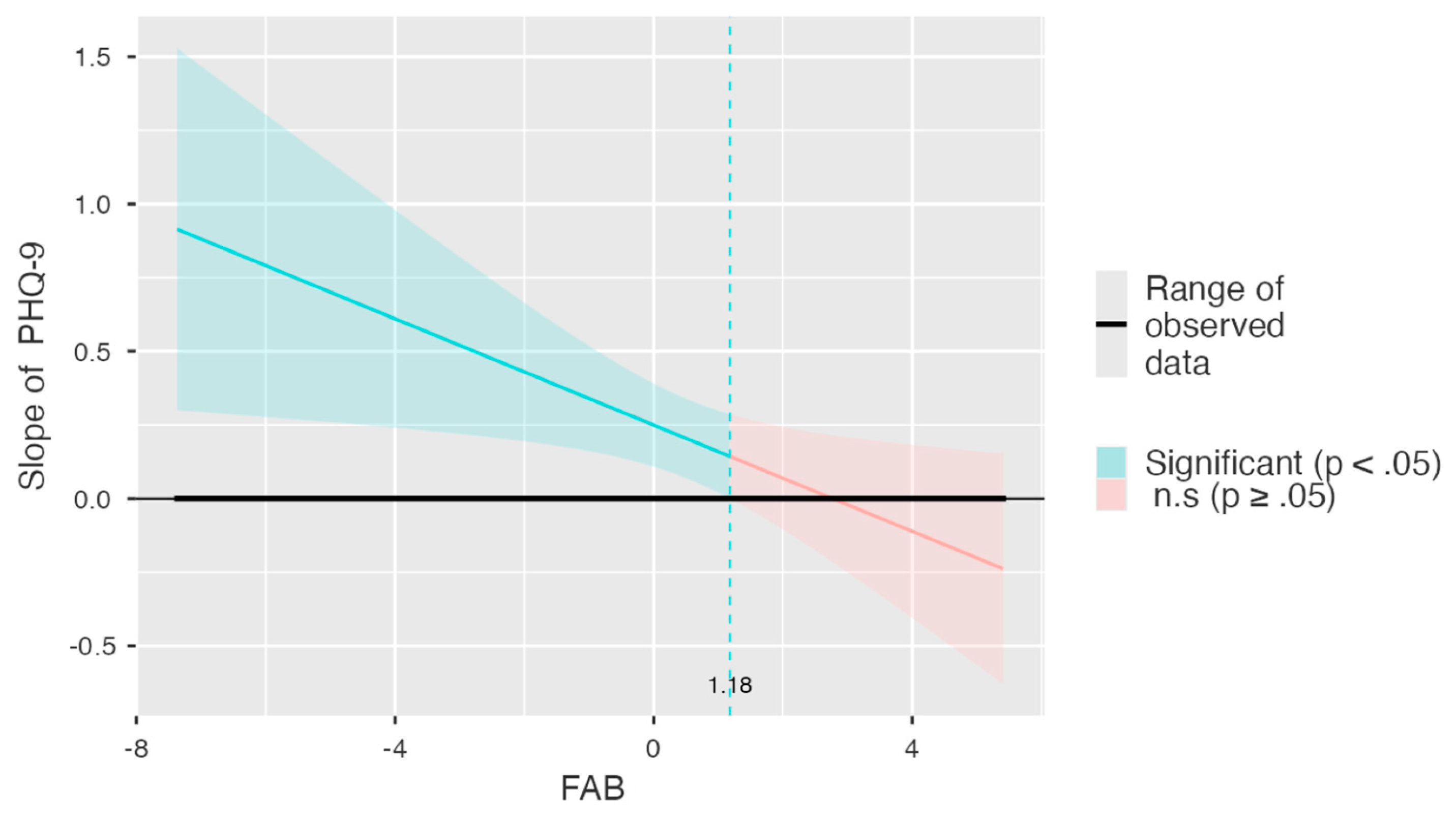

3.3. Moderation Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Strengths, Limits and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SCD | Subjective cognitive decline |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| MCI | Mild Cognitive Impairment |

| EFs | Executive functions |

| MASCoD | Multidimensional Assessment of Subjective Cognitive Decline |

| CCDDs | Centers for Cognitive Disorders and Dementias |

| DTCPs | Diagnostic Therapeutic Care Pathways |

| FAB | Frontal Assessment Battery |

| PHQ-9 | Patient Health Questionnaire-9 |

| CFI | Cognitive Functional Index |

References

- Jessen, F.; Amariglio, R.E.; van Boxtel, M.; Breteler, M.; Ceccaldi, M.; Chételat, G.; Dubois, B.; Dufouil, C.; Ellis, K.A.; van der Flier, W.M.; et al. A conceptual framework for research on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2014, 10, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jessen, F.; Amariglio, R.E.; Buckley, R.F.; van der Flier, W.M.; Han, Y.; Molinuevo, J.L.; Rabin, L.; Rentz, D.M.; Rodriguez-Gomez, O.; Saykin, A.J.; et al. The characterisation of subjective cognitive decline. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatini, S.; Woods, R.T.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Ballard, C.; Collins, R.; Clare, L. Associations of subjective cognitive and memory decline with depression, anxiety, and two-year change in objectively-assessed global cognition and memory. Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 2022, 29, 840–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, T.; Xing, G.; Han, Y. Subjective cognitive decline and related cognitive deficits. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röhr, S.; Pabst, A.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Jessen, F.; Turana, Y.; Handajani, Y.S.; Brayne, C.; Matthews, F.E.; Stephan, B.C.; Lipton, R.B.; et al. Estimating prevalence of subjective cognitive decline in and across international cohort studies of aging: A COSMIC study. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2020, 12, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappa, S.F.; Ribaldi, F.; Chicherio, C.; Frisoni, G.B. Subjective cognitive decline: Memory complaints, cognitive awareness, and metacognition. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, 6622–6631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, C.R., Jr.; Bennett, D.A.; Blennow, K.; Carrillo, M.C.; Dunn, B.; Haeberlein, S.B.; Holtzman, D.M.; Jagust, W.; Jessen, F.; Karlawish, J.; et al. NIA-AA research framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018, 14, 535–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribaldi, F.; Rolandi, E.; Vaccaro, R.; Colombo, M.; Battista Frisoni, G.; Guaita, A. The clinical heterogeneity of subjective cognitive decline: A data-driven approach on a population-based sample. Age Ageing 2022, 51, afac209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Liu, K.Y.; Costafreda, S.G.; Selbæk, G.; Alladi, S.; Ames, D.; Banerjee, S.; Burns, A.; Brayne, C.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the Lancet standing Commission. The Lancet 2024, 404, 572–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabin, L.A.; Smart, C.M.; Amariglio, R.E. Subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 13, 369–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebert, J.S.; Braun, T.; Wahl, H.W. Change in attitudes toward aging: Cognitive complaints matter more than objective performance. Psychol. Aging 2020, 35, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlatar, Z.Z.; Muniz, M.; Galasko, D.; Salmon, D.P. Subjective cognitive decline correlates with depression symptoms and not with concurrent objective cognition in a clinic-based sample of older adults. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2018, 73, 1198–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bessi, V.; Mazzeo, S.; Padiglioni, S.; Piccini, C.; Nacmias, B.; Sorbi, S.; Bracco, L. From Subjective Cognitive Decline to Alzheimer’s Disease: The Predictive Role of Neuropsychological Assessment, Personality Traits, and Cognitive Reserve. A 7-Year Follow-Up Study. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. JAD 2018, 63, 1523–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akinci, M.; Sánchez-Benavides, G.; Brugulat-Serrat, A.; Peña-Gómez, C.; Palpatzis, E.; Shekari, M.; Deulofeu, C.; Fuentes-Julian, S.; Salvadó, G.; González-De-Echávarri, J.M.; et al. Subjective cognitive decline and anxious/depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic: What is the role of stress perception, stress resilience, and β-amyloid? Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2022, 14, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, N.L.; Mogle, J.; Wion, R.; Munoz, E.; DePasquale, N.; Yevchak, A.M.; Parisi, J.M. Subjective cognitive impairment and affective symptoms: A systematic review. Gerontologist 2016, 56, e109–e127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffoni, M.; Magnani, A. Subjective cognitive decline. In The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Disability; Bennett, G., Goodall, E., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matcham, F.; Simblett, S.K.; Leightley, D.; Dalby, M.; Siddi, S.; Haro, J.M.; Lamers, F.; Penninx, B.W.H.J.; Bruce, S.; Nica, R.; et al. The association between persistent cognitive difficulties and depression and functional outcomes in people with major depressive disorder. Psychol. Med. 2023, 53, 6334–6344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamiya, A.; Casteele, T.V.; Koole, M.; De Winter, F.-L.; Bouckaert, F.; Stock, J.V.D.; Sunaert, S.; Dupont, P.; Vandenberghe, R.; Van Laere, K.; et al. Lower regional gray matter volume in the absence of higher cortical amyloid burden in late-life depression. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.H.; Han, D.H.; Min, K.J.; Kee, B.S. Correlation between gray matter volume in the temporal lobe and depressive symptoms in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2013, 548, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, E.; Liu, M.; Gong, S.; Fu, X.; Han, Y.; Deng, F. White matter alterations in depressive disorder. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 826812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Liu, S.; Li, X.; Chen, K.; Gao, S.; Wang, J.; Aarsland, D.; Han, Z.R.; Zhang, Z. Longitudinal association between depressive symptoms and cognitive function: The neurological mechanism of psychological and physical disturbances on memory. Psychol. Med. 2024, 54, 3602–3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; text rev; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, T.; Hadjipavlou, G.; Lam, R.W. Cognitive dysfunction in major depressive disorder: Assessment, impact, and management. Focus 2016, 14, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, T.M. Depression, subjective cognitive decline, and the risk of neurocognitive disorders. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2019, 11, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-M.; Han, K.-D.; Kim, N.-Y.; Um, Y.H.; Kang, D.-W.; Na, H.-R.; Lee, C.-U.; Lim, H.K. Late-life depression, subjective cognitive decline, and their additive risk in incidence of dementia: A nationwide longitudinal study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, M.; Nejati, V.; Shati, M.; Vatan, R.F.; Chehrehnegar, N.; Foroughan, M. Attentional network changes in subjective cognitive decline. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2022, 34, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smart, C.M.; Krawitz, A. The impact of subjective cognitive decline on Iowa Gambling Task performance. Neuropsychology 2015, 29, 971–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smart, C.M.; Segalowitz, S.J.; Mulligan, B.P.; MacDonald, S.W. Attention capacity and self-report of subjective cognitive decline: A P3 ERP study. Biol. Psychol. 2014, 103, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, S.; Cowan, N. Attention in working memory: Attention is needed but it yearns to be free. Ann. N. Y Acad. Sci. 2018, 1424, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, B.; Jonassen, R.; Stiles, T.C.; Landrø, N.I. Dysfunctional metacognitive beliefs are associated with decreased executive control. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Ding, X. Metacognitive deficits drive depression through a network of subjective and objective cognitive functions. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peräkylä, J.; Järventausta, K.; Haapaniemi, P.; Camprodon, J.A.; Hartikainen, K.M. Threat-modulation of executive functions—A novel biomarker of depression? Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 670974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H.R. Major depressive disorder is associated with broad impairments on neuropsychological measures of executive function: A meta-analysis and review. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 81–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maffoni, M.; Magnani, A.; Pierobon, A.; Mafferra, A.; Pasotti, F.; Dallocchio, C.; Chimento, P.; Torlaschi, V.; Trifirò, G.; Fundarò, C. The interplay between cognitive and psychological factors in subjective cognitive decline: Contribution to the validation of a new screening battery. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1670551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maffoni, M.; Pierobon, A.; Fundarò, C. MASCoD—Multidimensional assessment of subjective cognitive decline. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 921062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Pilot Randomized, Double-Blind, Sham-Controlled Trial of Noninvasive Brain Stimulation in Subjective Cognitive Decline (NCT05815329). ClinicalTrials.Gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05815329 (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Bacigalupo, I.; Giaquinto, F.; Salvi, E.; Carnevale, G.; Vaccaro, R.; Matascioli, F.; Remoli, G.; Vanacore, N.; Lorenzini, P. A new national survey of centers for cognitive disorders and dementias in Italy. Neurol. Sci. 2024, 45, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisoni, G.B.; Festari, C.; Massa, F.; Ramusino, M.C.; Orini, S.; Aarsland, D.; Agosta, F.; Babiloni, C.; Borroni, B.; Cappa, S.F.; et al. European intersocietal recommendations for the biomarker-based diagnosis of neurocognitive disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, E.N.; Esposito, A.; Gramegna, C.; Gazzaniga, V.; Zago, S.; Difonzo, T.; Appollonio, I.M.; Bolognini, N. The frontal assessment battery (FAB) and its sub-scales: Validation and updated normative data in an Italian population sample. Neurol. Sci. 2022, 43, 979–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, B.; Slachevsky, A.; Litvan, I.; Pillon, B. The FAB: A Frontal Assessment Battery at bedside. Neurology 2000, 55, 1621–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. JAMA 1999, 282, 1737–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipi, E.; Frattini, G.; Eusebi, P.; Mollica, A.; D’aNdrea, K.; Russo, M.; Bernardelli, A.; Montanucci, C.; Luchetti, E.; Calabresi, P.; et al. The Italian version of cognitive function instrument (CFI): Reliability and validity in a cohort of healthy elderly. Neurol. Sci. 2018, 39, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Jamovi Project. Jamovi [Computer Software], Version 2.6; The Jamovi Project: Sydney, Australia, 2025. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Cascio, W.F.; Barret, G. Setting cutoff scores: Legal, psychometric, and professional issues and guidelines. Pers. Psychol. 1988, 41, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tank, R.; Diaz, A.; Ashford, M.T.; Miller, M.J.; Eichenbaum, J.; Aaronson, A.; Landavazo, B.; Neuhaus, J.; Weiner, M.W.; Mackin, R.S.; et al. Examining demographic factors, psychosocial wellbeing and cardiovascular health in subjective cognitive decline in the Brain Health Registry cohort. J. Prev. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2024, 11, 787–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halaj, A.; Konstantakopoulos, G.; Ghaemi, N.S.; David, A.S. Anxiety Disorders: The Relationship between Insight and Metacognition. Psychopathology 2024, 57, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, M.; Hagen, J.; Ettinger, U. Unity and diversity of metacognition. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2022, 151, 2396–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbatore, I.; Conterio, R.; Vegna, G.; Bosco, F.M. Longitudinal assessment of pragmatic and cognitive decay in healthy aging, and interplay with subjective cognitive decline and cognitive reserve. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 30835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, S.; Levine, A.; Huber, B.; Andrews, H.; Kerner, N.A.; Cohen, D.; Carlson, S.; Bell, S.A.; Rivera, A.M.; et al. Novel measures of cognition and function for the AD spectrum in the Novel Measures for Alzheimer’s Disease Prevention Trials (NoMAD) project: Psychometric properties, convergent validation, and contrasts with established measures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, 5089–5101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, C.; Piccininni, C.; Iacobucci, G.M.; Caprara, A.; Gainotti, G.; Costantini, E.M.; Callea, A.; Venneri, A.; Quaranta, D. Semantic memory as an early cognitive marker of Alzheimer’s disease: Role of category and phonological verbal fluency tasks. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2021, 81, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fastame, M.C. Are subjective cognitive complaints associated with executive functions and mental health of older adults? Cogn. Process. 2022, 23, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Goh, W.Y.; Chan, D.; Ali, N.B.; Chew, A.P.; Chuo, A.; Chan, M.; Lim, W.S. Frontal Assessment Battery in Early Cognitive Impairment: Psychometric Property and Factor Structure. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2019, 23, 966–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, T. Self-report measures of executive function problems correlate with personality, not performance-based executive function measures, in nonclinical samples. Psychol. Assess. 2016, 28, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.M.; Haws, N.A.; Murphy-Tafiti, J.L.; Hubner, C.D.; Curtis, T.D.; Rupp, Z.W.; Smart, T.A.; Thompson, L.M. Are Self-Ratings of Functional Difficulties Objective or Subjective? Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult 2013, 20, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschwanden, D.; Sutin, A.R.; Luchetti, M.; Allemand, M.; Stephan, Y.; Terracciano, A. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Association between Personality and Cognitive Failures/Complaints. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2020, 14, e12565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffoni, M.; Pierobon, A.; Mancini, D.; Magnani, A.; Torlaschi, V.; Fundarò, C. How do you target cognitive training? Bridging the gap between standard and technological rehabilitation of cognitive domains. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1497642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sociodemographic Variables | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M ± SD | Min-Max | |

| Age | 69.28 ± 9.03 | 55–84 | |

| BMI | 25.79 ± 4.88 | 18.13–45.65 | |

| Variable | Levels | n | % of Total |

| Gender | Female | 46 | 70.8% |

| Male | 19 | 29.2% | |

| Study Title | Elementary school graduation | 12 | 18.5% |

| Junior high school | 21 | 32.3% | |

| High school graduation | 24 | 36.9% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 1 | 1.5% | |

| Master’s degree | 5 | 7.7% | |

| Postgraduate specialization | 2 | 3.1% | |

| Marital status | Single | 3 | 4.6% |

| Married/Cohabiting | 42 | 64.6% | |

| Widowed | 12 | 18.5% | |

| Separated/Divorced | 8 | 12.3% | |

| Employment Status | Self-employed | 4 | 6.2% |

| Full-time employee | 8 | 12.3% | |

| Part-time employee | 4 | 6.2% | |

| Homemaker | 4 | 6.2% | |

| Unemployed | 3 | 4.6% | |

| Retired | 42 | 64.6% | |

| Socio-family support | Spouse/Partner | 33 | 50.8% |

| Son/Daughter | 22 | 33.8% | |

| Parent | 0 | 0% | |

| Other Family Member | 2 | 3.1% | |

| Caretaker | 0 | 0% | |

| Other No Family Member | 0 | 0% | |

| Nobody | 8 | 12.3% | |

| Variable | Levels | N | % of Total |

| Physical Activity | Yes | 24 | 36.9% |

| No | 23 | 35.4% | |

| No response | 18 | 27.7% | |

| Smoking | Yes | 9 | 13.8% |

| No | 35 | 53.9% | |

| Former smoker | 18 | 27.7% | |

| No response | 3 | 4.6 | |

| Alcohol | Yes | 8 | 12.3% |

| No | 52 | 80.0% | |

| No response | 5 | 7.7% | |

| Family History of Cognitive Disorders | Yes | 30 | 46.15% |

| No | 30 | 46.15% | |

| No response | 5 | 7.7% | |

| Variable | n | Missing | Normative Value | M ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAB | 65 | 0 | ≥12.02 | 15.42 ± 2.11 |

| PHQ-9 | 65 | 0 | ≥5.00 | 6.57 ± 5.02 |

| CFI Self-report | 53 | 12 | ≥5.74 1 | 4.87 ± 2.57 |

| 95% Confidence Interval | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | Lower | Upper | β | t | df | p | |

| FAB | 0.198 | 0.176 | −0.155 | 0.551 | 0.155 | 1.125 | 49 | 0.266 |

| PHQ-9 | 0.250 | 0.070 | 0.108 | 0.391 | 0.470 | 3.552 | 49 | <0.001 |

| FAB × PHQ-9 | −0.090 | 0.038 | −0.166 | −0.015 | −0.343 | −2.396 | 49 | 0.020 |

| 95% Confidence Interval | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | Lower | Upper | β | t | df | p | |

| Mean − 1 SD | 0.635 | 0.300 | 0.033 | 1.237 | 0.498 | 2.119 | 49 | 0.039 |

| Mean | 0.198 | 0.176 | −0.155 | 0.551 | 0.155 | 1.125 | 49 | 0.266 |

| Mean + 1 SD | −0.239 | 0.196 | −0.634 | 0.155 | −0.188 | −1.219 | 49 | 0.229 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maffoni, M.; Magnani, A.; Pierobon, A.; Mafferra, A.; Pasotti, F.; Dallocchio, C.; Torlaschi, V.; Mancini, D.; Fundarò, C. Executive Functions and Subjective Cognitive Decline: The Moderating Role of Depressive Symptoms. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3164. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243164

Maffoni M, Magnani A, Pierobon A, Mafferra A, Pasotti F, Dallocchio C, Torlaschi V, Mancini D, Fundarò C. Executive Functions and Subjective Cognitive Decline: The Moderating Role of Depressive Symptoms. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3164. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243164

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaffoni, Marina, Annalisa Magnani, Antonia Pierobon, Alessandra Mafferra, Fabrizio Pasotti, Carlo Dallocchio, Valeria Torlaschi, Daniela Mancini, and Cira Fundarò. 2025. "Executive Functions and Subjective Cognitive Decline: The Moderating Role of Depressive Symptoms" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3164. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243164

APA StyleMaffoni, M., Magnani, A., Pierobon, A., Mafferra, A., Pasotti, F., Dallocchio, C., Torlaschi, V., Mancini, D., & Fundarò, C. (2025). Executive Functions and Subjective Cognitive Decline: The Moderating Role of Depressive Symptoms. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3164. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243164