Prognostic Value of CONUT and ALBI in Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer: A Retrospective Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Population

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CONUT | Controlling Nutritional Status |

| ALBI | Albumin–Bilirubin |

| LMR | Lymphocyte-to-Monocyte Ratio |

| NLR | Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio |

| ECOG | Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group |

| OS | Overall Survival |

| HR | Hazard Ratio |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

References

- Filho, A.M.; Laversanne, M.; Ferlay, J.; Colombet, M.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Parkin, D.M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. The GLOBOCAN 2022 cancer estimates: Data sources, methods, and a snapshot of the cancer burden worldwide. Int. J. Cancer 2025, 156, 1336–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizrahi, J.D.; Surana, R.; Valle, J.W.; Shroff, R.T. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet 2020, 395, 2008–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imamura, T.; Okamura, Y.; Sugiura, T.; Ito, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Ashida, R.; Ohgi, K.; Otsuka, S.; Uesaka, K. Clinical Significance of Preoperative Albumin-Bilirubin Grade in Pancreatic Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 28, 6223–6235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Zou, W.; Sun, Y. Prognostic Value of Pretreatment Controlling Nutritional Status Score for Patients with Pancreatic Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 770894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Wu, B.; Han, X.; Guo, C.; Li, B.; Jing, H.; Cheng, W. Prognostic value of albumin-bilirubin score in pancreatic cancer patients after pancreatoduodenectomy with liver metastasis following radiofrequency ablation. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2023, 29, 1611175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannangkoon, K.; Hongsakul, K.; Tubtawee, T.; Ina, N. Prognostic Value of Myosteatosis and Albumin-Bilirubin Grade for Survival in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Post Chemoembolization. Cancers 2024, 16, 3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignacio de Ulíbarri, J.; González-Madroño, A.; de Villar, N.G.; González, P.; González, B.; Mancha, A.; Rodríguez, F.; Fernández, G. CONUT: A tool for controlling nutritional status. First validation in a hospital population. Nutr. Hosp. 2005, 20, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, P.J.; Berhane, S.; Kagebayashi, C.; Satomura, S.; Teng, M.; Reeves, H.L.; O’Beirne, J.; Fox, R.; Skowronska, A.; Palmer, D.; et al. Assessment of liver function in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: A new evidence-based approach-the ALBI grade. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Yan, B. Prognostic and clinicopathological impacts of Controlling Nutritional Status (CONUT) score on patients with gynecological cancer: A meta-analysis. Nutr. J. 2023, 22, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuvanakrishna, T.; Wakefield, S. An invited commentary on “Prognostic significance of the controlling nutritional status (CONUT) score in patients with colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis” (Int. J. Surg. 78 (2020) 91-96). Int. J. Surg. 2020, 79, 50–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daitoku, N.; Miyamoto, Y.; Tokunaga, R.; Sakamoto, Y.; Hiyoshi, Y.; Iwatsuki, M.; Baba, Y.; Iwagami, S.; Yoshida, N.; Baba, H. Controlling Nutritional Status (CONUT) Score Is a Prognostic Marker in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients Receiving First-line Chemotherapy. Anticancer Res. 2018, 38, 4883–4888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toyoda, H.; Johnson, P.J. The ALBI score: From liver function in patients with HCC to a general measure of liver function. JHEP Rep. 2022, 4, 100557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Rahman, O. Prognostic Value of Baseline ALBI Score Among Patients with Colorectal Liver Metastases: A Pooled Analysis of Two Randomized Trials. Clin. Color. Cancer 2019, 18, e61–e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.G.; Lim, S.B.; Lee, J.L.; Kim, C.W.; Yoon, Y.S.; Park, I.J.; Kim, J.C. Preoperative albumin-bilirubin score as a prognostic indicator in patients with stage III colon cancer. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.N.; Ji, Y.; He, Y.L.; Jiang, X.Y. Performance of nutritional and inflammatory markers in patients with pancreatic cancer. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2024, 15, 1021–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, H.; Jang, J.; Kim, E.; Choi, J. Impact of nutritional changes on prognosis in pancreatic cancer: A longitudinal analysis. Nutrients 2025, 17, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimoyama, R.; Nakaji, S.; Fukuda, S. Inflammation-based prognostic markers for metastatic pancreatic cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2024, 27, 14269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartlapp, I.; Valta-Seufzer, D.; Siveke, J.T.; Algül, H.; Goekkurt, E.; Siegler, G.; Martens, U.M.; Waldschmidt, D.; Pelzer, U.; Fuchs, M.; et al. Prognostic and predictive value of CA 19-9 in locally advanced pancreatic cancer treated with multiagent induction chemotherapy: Results from a prospective, multicenter phase II trial (NEOLAP-AIO-PAK-0113). ESMO Open 2024, 7, 100552, Erratum in ESMO Open 2024, 9, 103705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirkin, K.A.; Hollenbeak, C.S.; Wong, J. Prognostic impact of carbohydrate antigen 19-9 level at diagnosis in resected stage I–III pancreatic adenocarcinoma: A U.S. population study. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2017, 8, 778–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamizawa, Y.; Shida, D.; Boku, N.; Nakamura, Y.; Ahiko, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Tanabe, T.; Takashima, A.; Kanemitsu, Y. Nutritional and inflammatory measures predict survival of patients with stage IV colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, M.; Demircan, N.C. The CONUT score is prognostic in esophageal cancer treated with chemoradiotherapy. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimose, S.; Kawaguchi, T.; Iwamoto, H.; Tanaka, M.; Miyazaki, K.; Ono, M.; Niizeki, T.; Shirono, T.; Okamura, S.; Nakano, M.; et al. Controlling Nutritional Status (CONUT) Score is Associated with Overall Survival in Patients with Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma Treated with Lenvatinib: A Multicenter Cohort Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, Z.M.; Timur, B. Albumin-Bilirubin Score: A Novel Mortality Predictor in Valvular Surgery. Braz. J. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2023, 38, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matysiak, K.; Hojdis, A.; Szewczuk, M. Controlling Nutritional Status (CONUT) Score as Prognostic Indicator in Stage IV Gastric Cancer with Chronic Intestinal Failure. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheirouri, S.; Alizadeh, M. Prognostic Potential of the Preoperative Controlling Nutritional Status (CONUT) Score in Predicting Survival of Patients with Cancer: A Systematic Review. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Score System | Component/Formula | Value Range | Score/Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| CONUT Score | Serum Albumin (g/dL) | ≥3.5 | 0 |

| 3.0–3.4 | 1 | ||

| 2.5–2.9 | 2 | ||

| <2.5 | 3 | ||

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | ≥180 | 0 | |

| 140–179 | 1 | ||

| 100–139 | 2 | ||

| <100 | 3 | ||

| Lymphocyte Count (cells/μL) | ≥1600 | 0 | |

| 1200–1599 | 1 | ||

| 800–1199 | 2 | ||

| <800 | 3 | ||

| Total CONUT Score | 0–9 | — | |

| Risk Classification | 0–1 | Low risk | |

| 2–4 | Moderate risk | ||

| 5–9 | High risk | ||

| ALBI Score | Formula | — | ALBI = (0.66 × log10(bilirubin μmol/L)) − (0.085 × albumin g/L) |

| Risk Classification | ≤−2.60 | Grade 1 (well-preserved liver function) | |

| >−2.60 | Grade 2 (impaired liver function) |

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 63.15 ± 9.39 years |

| Age (median, range) | 64 (34–86) |

| Age ≤65 years (%) | 59.4% |

| Age >65 years (%) | 40.6% |

| Gender (Male/Female) (%) | 61.5%/38.5% |

| ECOG Performance Status (0–1/≥2) (%) | 91.1% 8.9% |

| Pre-chemotherapy CA 19–9 ≤ 200 (>200) (%) | 56.8% (≤200)/43.2% (>200) |

| LMR (mean ± SD, median, range) | 3.25 ± 2.06, 2.8 (0.30–13.00) |

| LMR <2.8/>2.8 (%) | 50.5%/49.5% |

| NLR (mean ± SD, median, range) | 4.50 ± 4.53, 3.0 (0.70–32.50) |

| NLR <3/>3 (%) | 51.0%/49.0% |

| Liver Metastasis (Yes/No) (%) | 40.1%/59.9% |

| Lymph Node Metastasis (Yes/No) (%) | 88.0%/12.0% |

| Bone Metastasis (Yes/No) (%) | 13.5%/86.5% |

| CONUT Score (Low/Moderate/High) | 55.2%/40.6%/4.2% |

| ALBI Score (Grade 1/Grade 2) | 46.9%/53.1% |

| Follow-up Duration (mean ± SD, median, range) | 13.24 ± 3.17 months, 14.0 (5.0–21.0 months) |

| Treatment Category | Number of Patients | Percentage (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| FOLFIRINOX | 78 | 40.6 | First-line regimen |

| Gemcitabine + Nab-paclitaxel | 18 | 9.4 | First-line regimen |

| Gemcitabine monotherapy | 82 | 42.7 | Used in frail/ECOG ≥ 2 |

| Best supportive care only | 14 | 7.3 | No systemic therapy |

| ≥2 lines of therapy | 64 | 33.3 | Received second-line or more |

| Variable | 1-Year OS (%) | Median OS (Months, 95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| General | 78.1% | 14.00 (13.62–14.37) | N/A |

| Age | |||

| ≤65 years | 74.6% | 14.00 (13.49–14.50) | 0.048 |

| >65 years | 56.4% | 13.00 (12.28–13.71) | N/A |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 74.6% | 14.00 (13.41–14.58) | 0.599 |

| Female | 77.0% | 14.00 (13.54–14.45) | |

| ECOG Performance Status | |||

| 0–1 | 77.1% | 14.00 (13.61–14.38) | 0.175 |

| ≥2 | 88.2% | 14.00 (11.98–16.01) | |

| Pre-chemotherapy CA 19–9 | |||

| ≤200 | 69.7% | 14.00 (13.47–14.53) | 0.988 |

| >200 | 72.3% | 14.00 (13.48–14.51) | |

| LMR | |||

| <2.8 | 78.4% | 14.00 (13.40–14.59) | 0.283 |

| >2.8 | 77.9% | 14.00 (13.53–14.46) | |

| NLR | |||

| <3 | 78.6% | 14.00 (13.50–14.50) | 0.488 |

| >3 | 77.7% | 14.00 (13.44–14.55) | |

| Liver Metastasis | |||

| Yes | 79.1% | 14.00 (13.52–14.47) | 0.608 |

| No | 76.6% | 14.00 (13.33–14.66) | |

| Lymph Node Metastasis | |||

| Yes | 56.5% | 14.00 (11.70–16.29) | 0.812 |

| No | 79.3% | 14.00 (13.62–14.38) | |

| Bone Metastasis | |||

| Yes | 79.5% | 14.00 (13.61–14.39) | 0.121 |

| No | 69.2% | 13.00 (11.76–14.23) | |

| CONUT Score | |||

| Low | 78.3% | 14.00 (13.57–14.42) | <0.001 |

| Moderate | 78.2% | 14.00 (13.34–14.65) | |

| High | 12.5% | 7.80 (3.64–11.95) | |

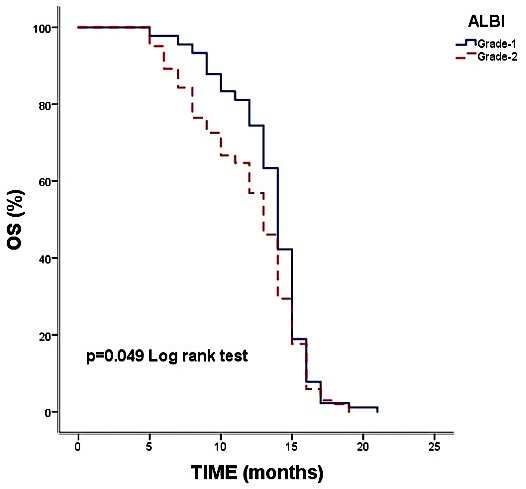

| ALBI Score | |||

| Grade 1 | 74.4% | 14.00 (13.51–14.48) | 0.049 |

| Grade 2 | 56.9% | 13.00 (12.29–13.70) |

| Variables | HR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| ≤65 | Ref (Reference) | |

| >65 | 1.13 (0.84–1.53) | 0.409 |

| CONUT | ||

| Low | Ref (Reference) | |

| Moderate | 0.85 (0.63–1.15) | 0.315 |

| High | 5.01 (2.27–10.98) | <0.001 |

| ALBI | ||

| Grade 1 | Ref (Reference) | |

| Grade 2 | 17.86 (9.63–31.04) | <0.001 |

| ECOG | ||

| 0–1 | Ref(Reference) | |

| >2 | 1.41 (0.92–2.15) | 0.112 |

| Liver Metastasis | ||

| No | Ref(Reference) | |

| Yes | 1.18 (0.79–1.76) | 0.416 |

| First-line regimen | ||

| Folfirox | Ref(Reference) | |

| Others | 0.74 (0.51–1.09) | 0.127 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peker, P.; Geçgel, A.; Yılmaz, S.; Cırık, C.; Selvi, S.; Bozkurt Duman, B.; Çil, T. Prognostic Value of CONUT and ALBI in Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3161. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243161

Peker P, Geçgel A, Yılmaz S, Cırık C, Selvi S, Bozkurt Duman B, Çil T. Prognostic Value of CONUT and ALBI in Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3161. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243161

Chicago/Turabian StylePeker, Pınar, Aslı Geçgel, Serdar Yılmaz, Cafer Cırık, Seher Selvi, Berna Bozkurt Duman, and Timuçin Çil. 2025. "Prognostic Value of CONUT and ALBI in Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer: A Retrospective Cohort Study" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3161. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243161

APA StylePeker, P., Geçgel, A., Yılmaz, S., Cırık, C., Selvi, S., Bozkurt Duman, B., & Çil, T. (2025). Prognostic Value of CONUT and ALBI in Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3161. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243161