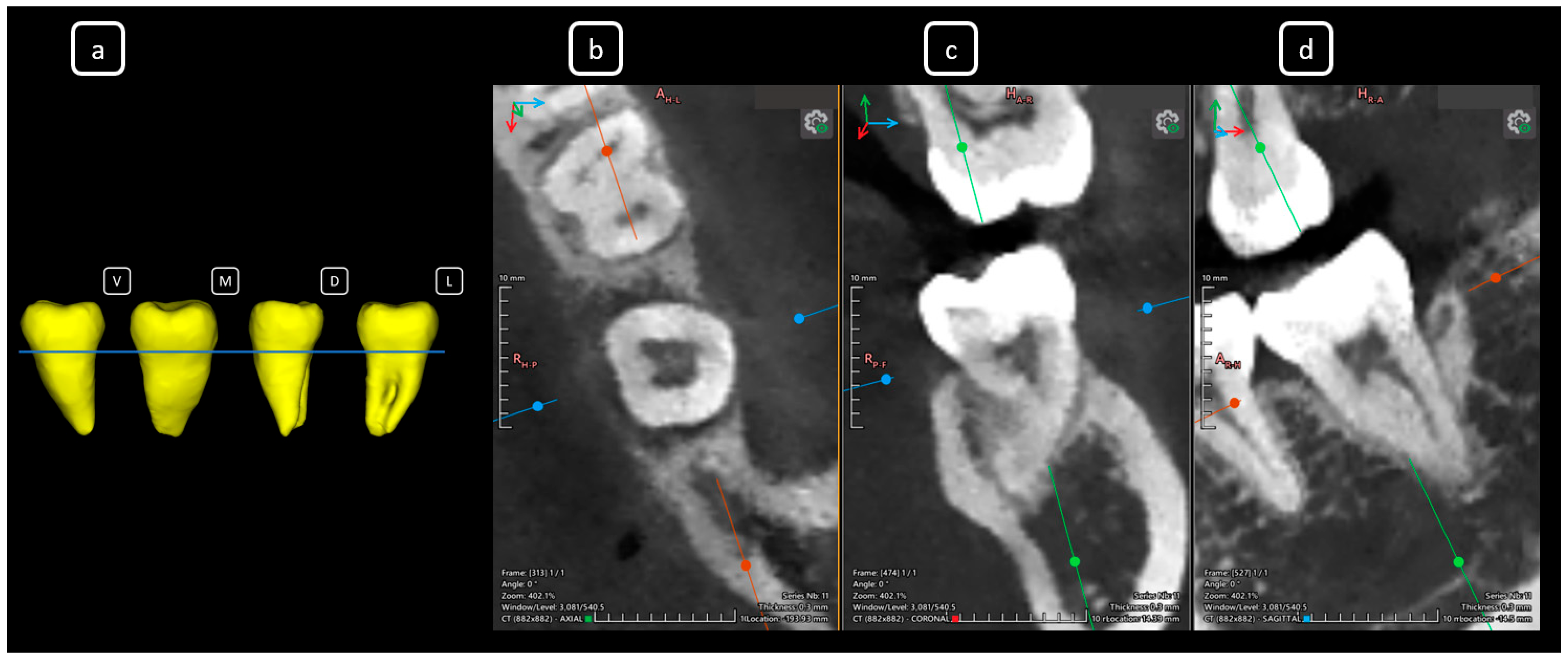

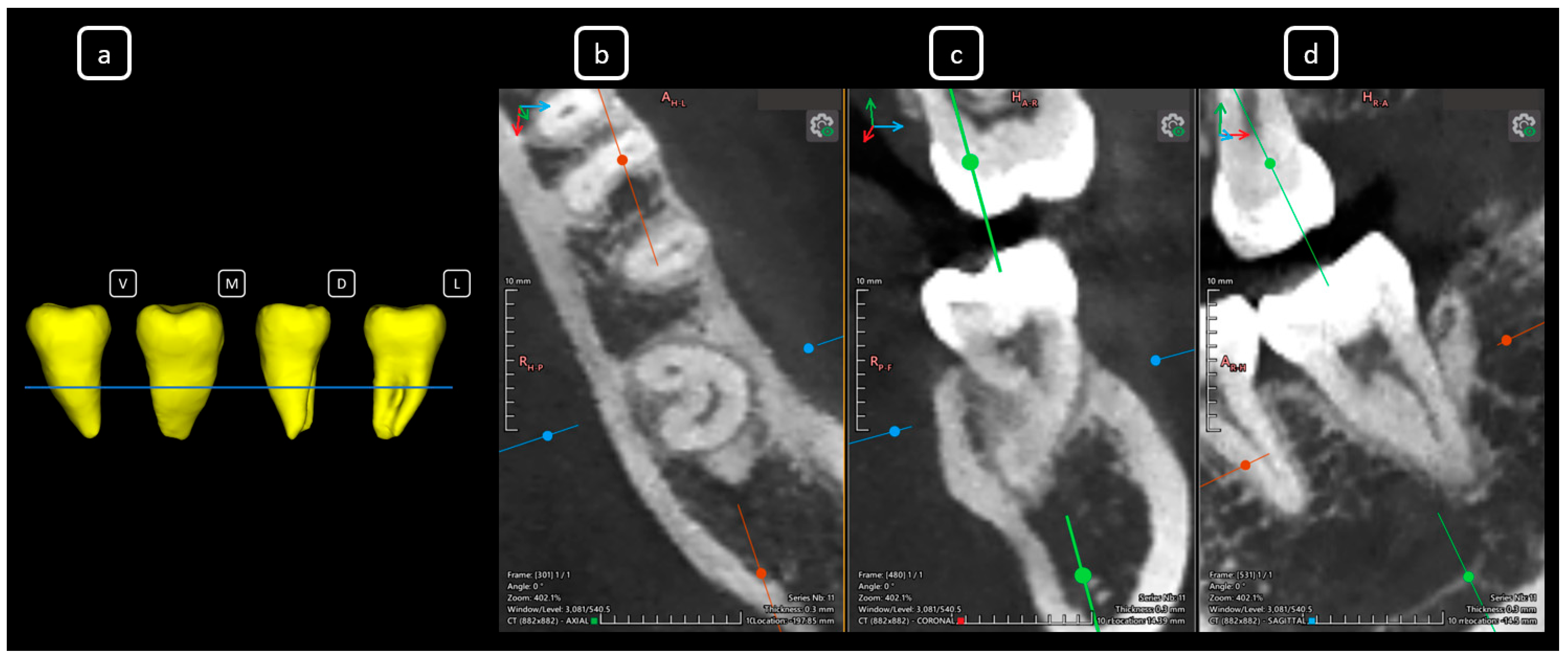

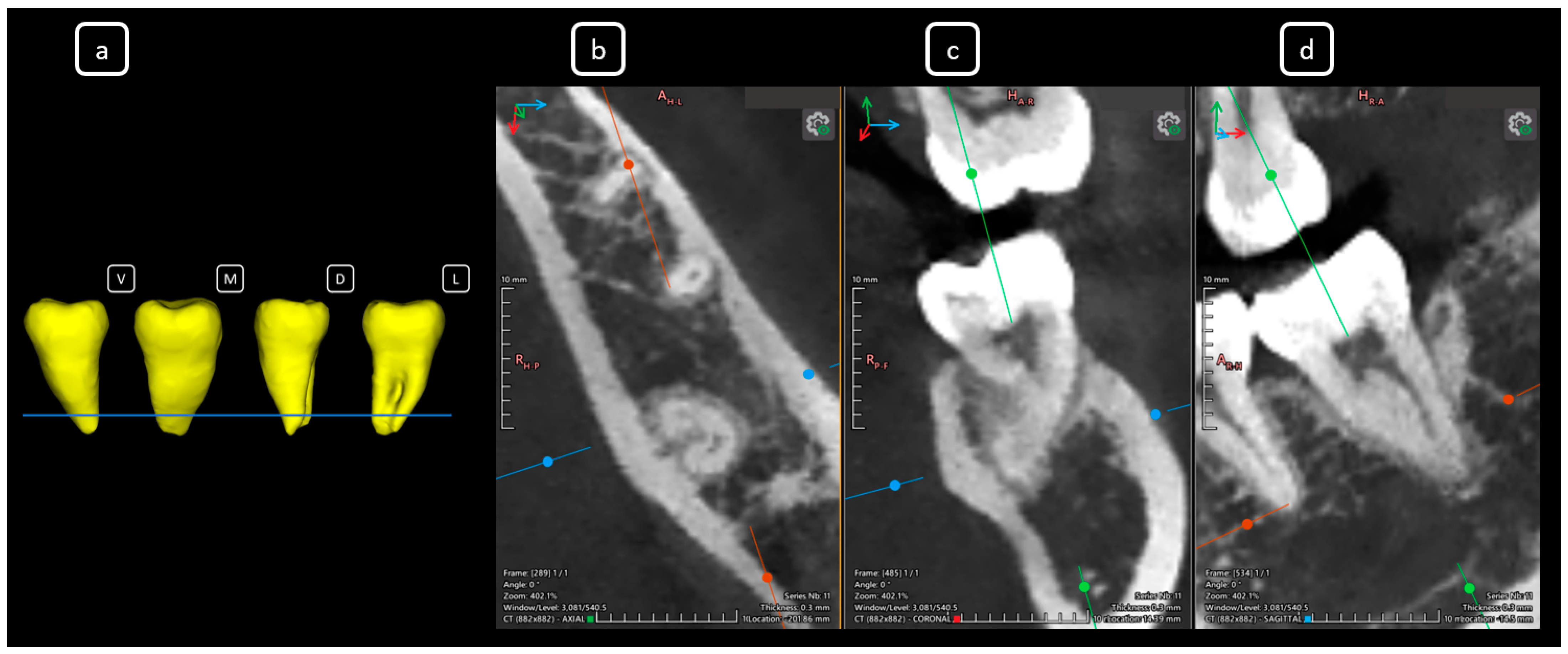

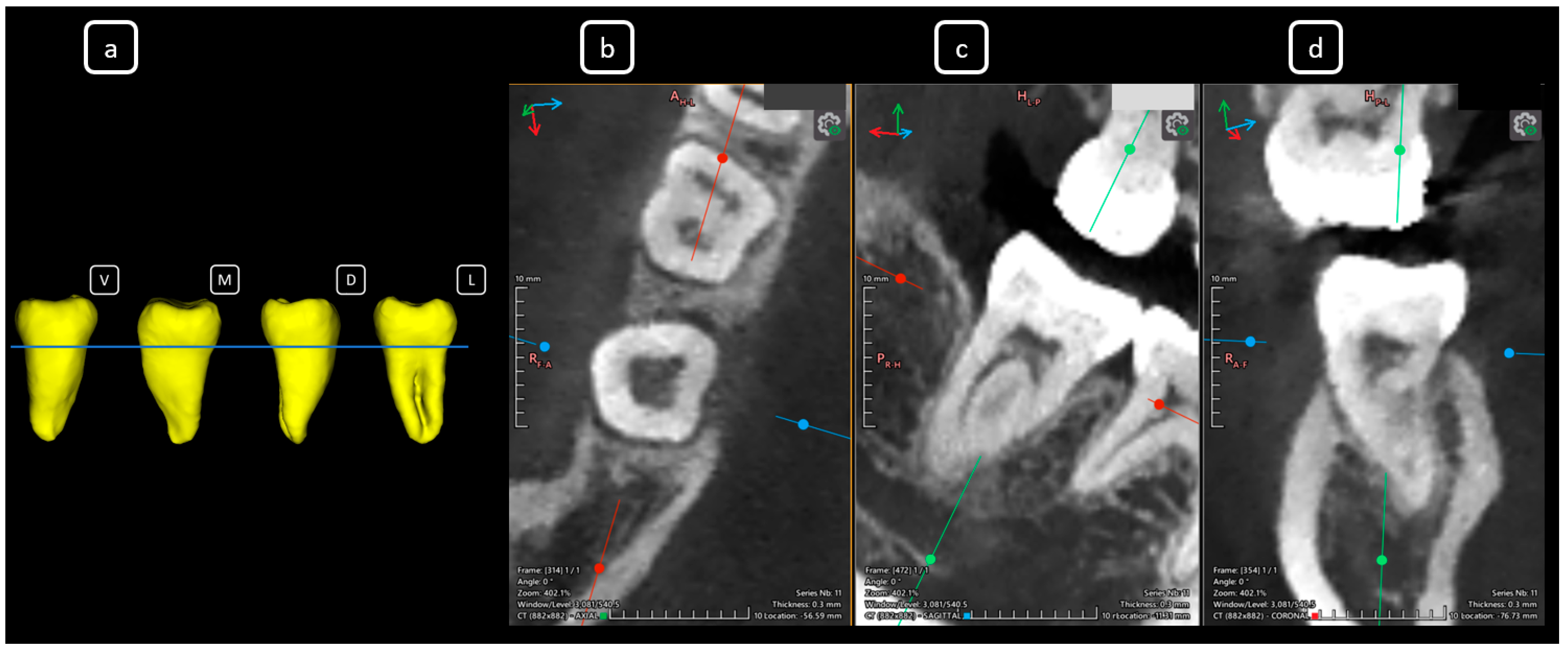

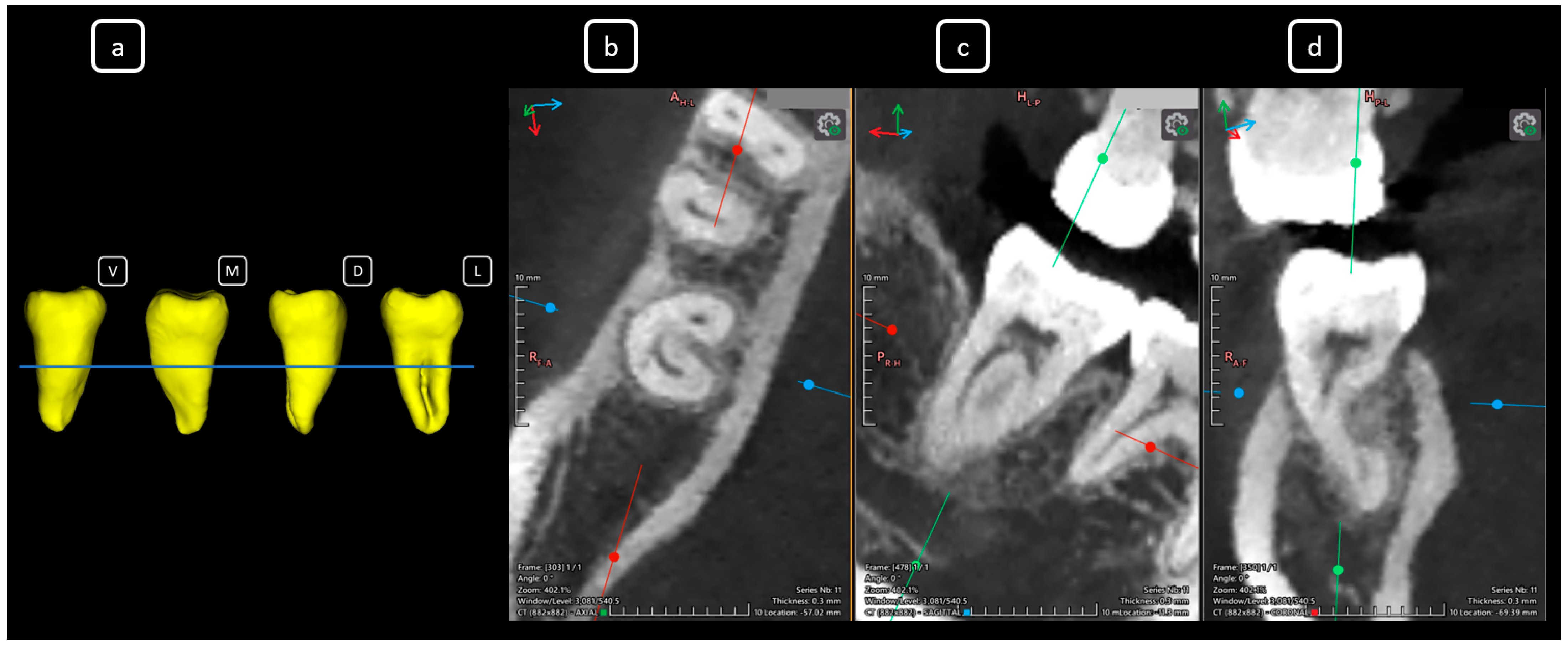

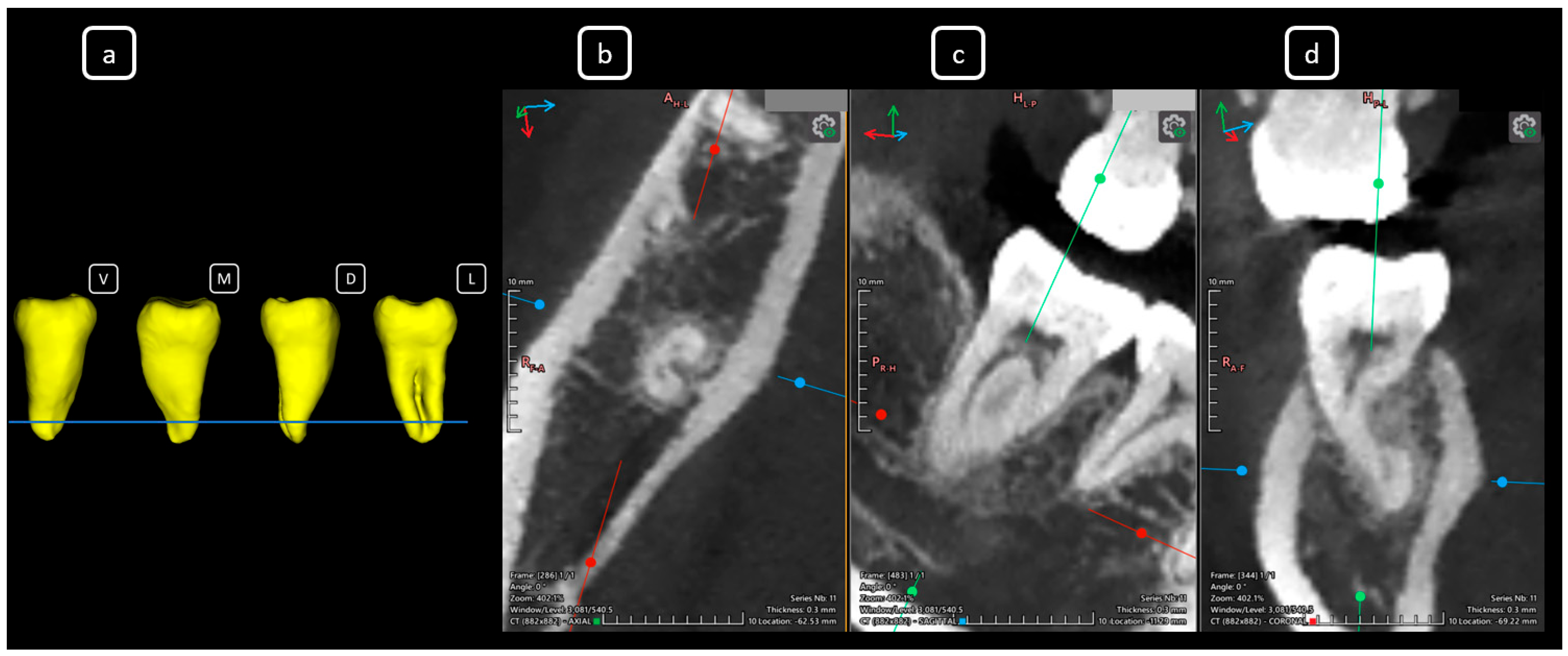

Imaging Findings of Clinical Significance in Endodontics During Cone Beam Computed Tomography Scanning of the Upper Airway—The Anterior, Bilateral, C-Shaped, Dual of Mandibular Root Canals: A Brief Case Report

Abstract

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBCT | Cone beam computed tomography |

| UJED | Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango |

| NAO | Nasal Airway Obstruction |

| FDI | Fédération dentaire internationale—The FDI World Dental Federation |

| ESE | European Society of Endodontology |

| FOV | Field of View |

References

- Echarri-Nicolás, J.; González-Olmo, M.J.; Echarri-Labiondo, P.; Romero, M. Short-term outcomes in the upper airway with tooth-bone-borne vs bone-borne rapid maxillary expanders. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.W.; Del Signore, A.G.; Raithatha, R.; Senior, B.A. Nasal airway obstruction: Prevalence and anatomic contributors. Ear Nose Throat J. 2018, 97, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajendra Santosh, A.B.; Jones, T. Enhancing Precision: Proposed Revision of FDI’s 2-Digit Dental Numbering System. Int. Dent. J. 2024, 74, 359–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertucci, F.J. Root canal anatomy of the human permanent teeth. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1984, 58, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.; Saberi, N.; Pimental, T.; Teng, P.H. Present status and future directions: Root resorption. Int. Endod. J. 2022, 55, 892–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Patel, S.; Krastl, G.; Weiger, R.; Lambrechts, P.; Tjäderhane, L.; Gambarini, G.; Teng, P.H. ESE position statement on root resorption. Int. Endod. J. 2023, 56, 792–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, J.N.R.; Worldwide Anatomy Research Group; Versiani, M.A. Worldwide Prevalence of the Lingual Canal in Mandibular Incisors: A Multicenter Cross-sectional Study with Meta-analysis. J. Endod. 2023, 49, 819–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, J.N.R.; Worldwide Anatomy Research Group; Versiani, M.A. Worldwide Anatomic Characteristics of the Mandibular Canine-A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study with Meta-Analysis. J. Endod. 2024, 50, 456–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sroczyk-Jaszczyńska, M.; Kołecki, J.; Lipski, M.; Puciło, M.; Wilk, G.; Falkowski, A.; Kot, K.; Nowicka, A. A study of the symmetry of roots and root canal morphology in mandibular anterior teeth using cone-beam computed tomographic imaging in a Polish population. Folia Morphol. 2020, 79, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood Talabani, R. Assessment of root canal morphology of mandibular permanent anterior teeth in an Iraqi subpopulation by cone-beam computed tomography. J. Dent. Sci. 2021, 16, 1182–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Candeiro, G.T.; Teixeira, I.M.M.D.; Barbosa, D.A.O.; Vivacqua-Gomes, N.; Alves, F.R. Vertucci’s Root Canal Configuration of 14,413 Mandibular Anterior Teeth in a Brazilian Population: A Prevalence Study Using Cone-beam Computed Tomography. J. Endod. 2021, 47, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nepal, M.; Chakradhar, A.; Pradhan, S.P.; Khadka, J.; Tripathi, R.; Bali, H. Cone-beam computed tomographic study of the internal anatomy of lower anterior teeth. Kathmandu Univ. Med. J. 2024, 22, 221–227. [Google Scholar]

- Taha, N.A.; Makahleh, N.; Hatipoglu, F.P. Root canal morphology of anterior permanent teeth in Jordanian population using two classification systems: A cone-beam computed tomography study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fan, B.; Cheung, G.S.; Fan, M.; Gutmann, J.L.; Bian, Z. C-shaped canal system in mandibular second molars: Part I--Anatomical features. J. Endod. 2004, 30, 899–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Zuben, M.; Martins, J.N.R.; Berti, L.; Cassim, I.; Flynn, D.; Gonzalez, J.A.; Gu, Y.; Kottoor, J.; Monroe, A.; Rosas Aguilar, R.; et al. Worldwide Prevalence of Mandibular Second Molar C-Shaped Morphologies Evaluated by Cone-Beam Computed Tomography. J. Endod. 2017, 43, 1442–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mingo, E.; Noguera, M.; Jiménez, F.; Ballester, M.L.; Berástegui, E. Prevalence and morphology of lower second molars with C-Shaped canals: A CBCT analysis. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2025, 17, e160–e167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zheng, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Tang, L.; Song, F.; Huang, D. C-shaped root canal system in mandibular second molars in a Chinese population evaluated by cone-beam computed tomography. Int. Endod. J. 2011, 44, 857–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.S.; Jung, D.; Lee, H.; Han, Y.S.; Oh, S.; Sim, H.Y. C-shaped root canals of mandibular second molars in a Korean population: A CBCT analysis. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2018, 43, e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lee, T.Y.; Yang, S.E.; Kim, K.J. Erratum to “Prevalence and Morphology of C-Shaped Canals: A CBCT Analysis in a Korean Population”. Scanning 2022, 2022, 9841276, Erratum in Scanning 2021, 2021, 9152004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pataer, M.; Abulizi, A.; Jumatai, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, J. C-shaped canal configuration in mandibular second molars of a selected Uyghur adults in Xinjiang: Prevalence, correlation, and differences of root canal configuration using cone-beam computed tomography. BMC Med. Imaging 2025, 25, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Helvacioglu-Yigit, D.; Sinanoglu, A. Use of cone-beam computed tomography to evaluate C-shaped root canal systems in mandibular second molars in a Turkish subpopulation: A retrospective study. Int. Endod. J. 2013, 46, 1032–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfawaz, H.; Alqedairi, A.; Alkhayyal, A.K.; Almobarak, A.A.; Alhusain, M.F.; Martins, J.N.R. Prevalence of C-shaped canal system in mandibular first and second molars in a Saudi population assessed via cone beam computed tomography: A retrospective study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2019, 23, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khawaja, S.; Alharbi, N.; Chaudhry, J.; Khamis, A.H.; Abed, R.E.; Ghoneima, A.; Jamal, M. The C-shaped root canal systems in mandibular second molars in an Emirati population. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Al Omari, T.; AlKhader, M.; Ateş, A.A.; Wahjuningrum, D.A.; Dkmak, A.; Khaled, W.; Alzenate, H. A CBCT based cross sectional study on the prevalence and anatomical feature of C shaped molar among Jordanian. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abdalrahman, K.; Talabani, R.; Kazzaz, S.; Babarasul, D. Assessment of C-Shaped Canal Morphology in Mandibular and Maxillary Second Molars in an Iraqi Subpopulation Using Cone-Beam Computed Tomography. Scanning 2022, 2022, 4886993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ladeira, D.B.; Cruz, A.D.; Freitas, D.Q.; Almeida, S.M. Prevalence of C-shaped root canal in a Brazilian subpopulation: A cone-beam computed tomography analysis. Braz. Oral Res. 2014, 28, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laplace, J.F.; Ferreccio, J.G.; Malvicini, G.; Mendez de la Espriella, C.; Pérez, A.R. Prevalence and Morphology of C-Shaped Canals in Mandibular Second Molars: A Cross-Sectional Cone Beam Computed Tomography Study in an Ecuadorian Population. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemesh, A.; Levin, A.; Katzenell, V.; Itzhak, J.B.; Levinson, O.; Avraham, Z.; Solomonov, M. C-shaped canals-prevalence and root canal configuration by cone beam computed tomography evaluation in first and second mandibular molars-a cross-sectional study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2017, 21, 2039–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenelon, T.; Parashos, P. Prevalence and morphology of C-shaped and non-C-shaped root canal systems in mandibular second molars. Aust. Dent. J. 2022, 67, S65–S75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feghali, M.; Jabre, C.; Haddad, G. Anatomical Investigation of C-shaped Root Canal Systems of Mandibular Molars in a Middle Eastern Population: A CBCT Study. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2022, 23, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mozzo, P.; Procacci, C.; Tacconi, A.; Martini, P.T.; Andreis, I.A. A new volumetric CT machine for dental imaging based on the cone-beam technique: Preliminary results. Eur. Radiol. 1998, 8, 1558–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, Y.; Tammisalo, E.; Iwai, K.; Hashimoto, K.; Shinoda, K. Development of a compact computed tomographic apparatus for dental use. Dento Maxillo Facial Radiol. 1999, 28, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, E.; Elluru, S.V. Cone beam computed tomography: Basics and applications in dentistry. J. Istanb. Univ. Fac. Dent. 2017, 51, S102–S121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spin-Neto, R.; Marcantonio, E., Jr.; Gotfredsen, E.; Wenzel, A. Exploring CBCT-based DICOM files. A systematic review on the properties of images used to evaluate maxillofacial bone grafts. J. Digit. Imaging 2011, 24, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pereira, H.; Romero, L.; Miguel Faria, P. Web-Based DICOM Viewers: A Survey and a Performance Classification. J. Digit. Imaging Inform. Med. 2025, 38, 1304–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, C.; Cavadas, F.; Fonseca, P. Upper Airway Assessment in Cone-Beam Computed Tomography for Screening of Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome: Development of an Evaluation Protocol in Dentistry. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2023, 12, e41049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zimmerman, J.N.; Vora, S.R.; Pliska, B.T. Reliability of upper airway assessment using CBCT. Eur. J. Orthod. 2019, 41, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgiadis, T.; Angelopoulos, C.; Papadopoulos, M.A.; Kolokitha, O.E. Three-Dimensional Cone-Beam Computed Tomography Evaluation of Changes in Naso-Maxillary Complex Associated with Rapid Palatal Expansion. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsolakis, I.A.; Kolokitha, O.E. Comparing Airway Analysis in Two-Time Points after Rapid Palatal Expansion: A CBCT Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastan, F.; Ghaffari, H.; Shishvan, H.H.; Zareiyan, M.; Akhlaghian, M.; Shahab, S. Correlation between the upper airway volume and the hyoid bone position, palatal depth, nasal septum deviation, and concha bullosa in different types of malocclusion: A retrospective cone-beam computed tomography study. Dent. Med. Probl. 2021, 58, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Harvey, S. Guidelines for reporting on CBCT scans. Int. Endod. J. 2021, 54, 628–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.; Brown, J.; Pimentel, T.; Kelly, R.D.; Abella, F.; Durack, C. Cone beam computed tomography in Endodontics-a review of the literature. Int. Endod. J. 2019, 52, 1138–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzi-Chaves, J.F.; Camargo, R.V.; Borges, A.F.; Silva, R.G.; Pauwels, R.; Silva-Sousa, Y.T.C.; Sousa-Neto, M.D. Cone-beam computed tomography in endodontics—State of the art. Curr. Oral Health Rep. 2021, 8, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Osorio, N.; Quijano-Guauque, S.; Briñez-Rodríguez, S.; Velasco-Flechas, G.; Muñoz-Solís, A.; Chávez, C.; Fernandez-Grisales, R. Cone-beam computed tomography in endodontics: From the specific technical considerations of acquisition parameters and interpretation to advanced clinical applications. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2023, 49, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brown, J.; Jacobs, R.; Jäghagen, E.L.; Lindh, C.; Baksi, G.; Schulze, D.; Schulze, R.; European Academy of Dento MaxilloFacial Radiology. Basic training requirements for the use of dental CBCT by dentists: A position paper prepared by the European Academy of DentoMaxilloFacial Radiology. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2014, 43, 20130291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- European Society of Endodontology; Patel, S.; Durack, C.; Abella, F.; Roig, M.; Shemesh, H.; Lambrechts, P.; Lemberg, K. European Society of Endodontology position statement: The use of CBCT in endodontics. Int. Endod. J. 2014, 47, 502–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chugal, N.; Assad, H.; Markovic, D.; Mallya, S.M. Applying the American Association of Endodontists and American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology guidelines for cone-beam computed tomography prescription: Impact on endodontic clinical decisions. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2024, 155, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, M.; Coil, J.; Chehroudi, B.; Esteves, A.; Aleksejuniene, J.; MacDonald, D. Clinical decision-making and importance of the AAE/AAOMR position statement for CBCT examination in endodontic cases. Int. Endod. J. 2021, 54, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, R.M.S.; Copelli, F.A.; Pinto, J.C.; Tanomaru-Filho, M.; Duarte, M.A.H.; Cavenago, B.C. Shaping ability of three heat-treated NiTi systems in Vertucci’s type III root canals of mandibular incisors: An ex vivo study. Saudi Dent. J. 2024, 36, 568–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavenago, B.C.; Leal, R.M.D.S.; Copelli, F.A.; Batista, A.; Michelotto, A.L.D.C.; Ordinola-Zapata, R.; Duarte, M.A.H. Root canal anatomy of mandibular incisors with Vertucci’s type III configuration: A micro-CT evaluation. G. Ital. Di Endod. 2024, 39, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzankovic, A.; Korac, S.; Tahmiscija, I.; Hadziabdic, N. Endodontic Challenges Arising from Root Canal Morphology; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagadi, E.; Muryani, A.; Adang, R.A.F. Integrated Endodontic and Restorative Management of C-Shaped Canals with Severe Coronal Loss in Mandibular Second Molar: A Case Report. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2025, 17, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gagnier, J.J.; Kienle, G.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D.; Sox, H.; Riley, D.; the CARE Group. The CARE Guidelines: Consensus-based Clinical Case Reporting Guideline Development. Glob. Adv. Health Med. 2013, 2, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, D.S.; Barber, M.S.; Kienle, G.S.; Aronson, J.K.; von Schoen-Angerer, T.; Tugwell, P.; Kiene, H.; Helfand, M.; Altman, D.G.; Sox, H.; et al. CARE guidelines for case reports: Explanation and elaboration document. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017, 89, 218–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nissen, T.; Wynn, R. The clinical case report: A review of its merits and limitations. BMC Res. Notes 2014, 7, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Torres, E.; Guerrero-Falcón, D.L.G.; Bojórquez-Armenta, H.A.; Almeda-Ojeda, O.E.; Barajas-Pérez, V.H.; Solís-Martínez, L.J. Imaging Findings of Clinical Significance in Endodontics During Cone Beam Computed Tomography Scanning of the Upper Airway—The Anterior, Bilateral, C-Shaped, Dual of Mandibular Root Canals: A Brief Case Report. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3157. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243157

García-Torres E, Guerrero-Falcón DLG, Bojórquez-Armenta HA, Almeda-Ojeda OE, Barajas-Pérez VH, Solís-Martínez LJ. Imaging Findings of Clinical Significance in Endodontics During Cone Beam Computed Tomography Scanning of the Upper Airway—The Anterior, Bilateral, C-Shaped, Dual of Mandibular Root Canals: A Brief Case Report. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3157. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243157

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Torres, Edgar, Diana Laura Grissel Guerrero-Falcón, Hugo Alejandro Bojórquez-Armenta, Oscar Eduardo Almeda-Ojeda, Víctor Hiram Barajas-Pérez, and Luis Javier Solís-Martínez. 2025. "Imaging Findings of Clinical Significance in Endodontics During Cone Beam Computed Tomography Scanning of the Upper Airway—The Anterior, Bilateral, C-Shaped, Dual of Mandibular Root Canals: A Brief Case Report" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3157. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243157

APA StyleGarcía-Torres, E., Guerrero-Falcón, D. L. G., Bojórquez-Armenta, H. A., Almeda-Ojeda, O. E., Barajas-Pérez, V. H., & Solís-Martínez, L. J. (2025). Imaging Findings of Clinical Significance in Endodontics During Cone Beam Computed Tomography Scanning of the Upper Airway—The Anterior, Bilateral, C-Shaped, Dual of Mandibular Root Canals: A Brief Case Report. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3157. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243157