Vascular Calcification Patterns in the Elderly: Correlation Between Aortic and Iliac Calcification Burden

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Assessment of Vascular Calcification

2.2.1. Abdominal Aortic Calcification

2.2.2. Iliac Artery Calcification

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Distribution of Vascular Calcification

3.3. Correlation and Categorical Associations of Vascular Calcification

3.4. Multivariable Linear Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AACS | Abdominal aorta calcification score |

| AF | Atrial fibrillation |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| CAD | Coronary artery disease |

| CHF | Chronic heart failure |

| CIA | Common iliac artery |

| CIACS | Common iliac artery calcification score |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| df | Degrees of freedom |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| EIA | External iliac artery |

| EIACS | External iliac artery calcification score |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| NCD | Neurocognitive disorder |

| PACS | Picture Archiving and Communication System |

| TIA | Transient ischaemic attack |

| TIACS | Total iliac artery calcification score |

References

- Tesauro, M.; Mauriello, A.; Rovella, V.; Annicchiarico-Petruzzelli, M.; Cardillo, C.; Melino, G.; Di Daniele, N. Arterial ageing: From endothelial dysfunction to vascular calcification. J. Intern. Med. 2017, 281, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, A.; Goldstein, D.R.; Sutton, N.R. Age-associated arterial calcification: The current pursuit of aggravating and mitigating factors. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2020, 31, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demer, L.L.; Tintut, Y. Inflammatory, metabolic, and genetic mechanisms of vascular calcification. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2014, 34, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pescatore, L.A.; Gamarra, L.F.; Liberman, M. Multifaceted Mechanisms of Vascular Calcification in Aging. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2019, 39, 1307–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Lee, I.K.; Jeon, J.H. Vascular Calcification-New Insights into Its Mechanism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, M.J.; Müller, P.; Lechner, K.; Stiebler, M.; Arndt, P.; Kunz, M.; Ahrens, D.; Schmeißer, A.; Schreiber, S.; Braun-Dullaeus, R.C. Arterial stiffness and vascular aging: Mechanisms, prevention, and therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, H.; Li, R.; Guo, S.; Wu, S.; Guo, X. Associations Between Life’s Essential 8 and Abdominal Aortic Calcification Among Middle-Aged and Elderly Populations. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e031146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuang, M.L.; Massaro, J.M.; Levitzky, Y.S.; Fox, C.S.; Manders, E.S.; Hoffmann, U.; O’DOnnell, C.J. Prevalence and distribution of abdominal aortic calcium by gender and age group in a community-based cohort (from the Framingham Heart Study). Am. J. Cardiol. 2012, 110, 891–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, M.A.; Criqui, M.H.; Wright, C.M. Patterns and risk factors for systemic calcified atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004, 24, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamenskiy, A.; Poulson, W.; Sim, S.; Reilly, A.; Luo, J.; MacTaggart, J. Prevalence of Calcification in Human Femoropopliteal Arteries and its Association with Demographics, Risk Factors, and Arterial Stiffness. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018, 38, e48–e57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jadidi, M.; Poulson, W.; Aylward, P.; MacTaggart, J.; Sanderfer, C.; Marmie, B.; Pipinos, M.; Kamenskiy, A. Calcification prevalence in different vascular zones and its association with demographics, risk factors, and morphometry. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2021, 320, H2313–H2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenknecht, L.E.; Langefeld, C.D.; Freedman, B.I.; Carr, J.J.; Bowden, D.W. A comparison of risk factors for calcified atherosclerotic plaque in the coronary, carotid, and abdominal aortic arteries: The diabetes heart study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007, 166, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Li, N.; Gao, Y.; Jiang, H.; Shen, Y. Prevalence and risk factors for vascular calcification based on the ankle-brachial index in the general population: A cross-sectional study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2022, 22, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, R.L.; Chung, H.; Detrano, R.; Post, W.; Kronmal, R.A. Distribution of coronary artery calcium by race, gender, and age: Results from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation 2006, 113, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensky, N.E.; Criqui, M.H.; Wright, M.C.; Wassel, C.L.; Brody, S.A.; Allison, M.A. Blood pressure and vascular calcification. Hypertension 2010, 55, 990–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.G.; Wu, L.T.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, E.D.; Yoon, S.J. Relationship between Smoking and Abdominal Aorta Calcification on Computed Tomography. Korean J. Fam. Med. 2019, 40, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbang, N.I.; McClelland, R.L.; Remigio-Baker, R.A.; Allison, M.A.; Sandfort, V.; Michos, E.D.; Thomas, I.; Rifkin, D.E.; Criqui, M.H. Associations of cardiovascular disease risk factors with abdominal aortic calcium volume and density: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Atherosclerosis 2016, 255, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutouyrie, P.; Chowienczyk, P.; Humphrey, J.D.; Mitchell, G.F. Arterial stiffness and cardiovascular risk in hypertension. Circ. Res. 2021, 128, 864–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demer, L.L.; Tintut, Y. Vascular calcification: Pathobiology of a multifaceted disease. Circulation 2008, 117, 2938–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoncini, G.; Ratto, E.; Viazzi, F.; Vaccaro, V.; Parodi, A.; Falqui, V.; Conti, N.; Tomolillo, C.; Deferrari, G.; Pontremoli, R. Increased ambulatory arterial stiffness index is associated with target organ damage in primary hypertension. Hypertension 2006, 48, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennenberg, R.J.M.W.; Kessels, A.G.H.; Schurgers, L.J.; Van Engelshoven, J.M.A.; De Leeuw, P.W.; Kroon, A.A. Vascular calcifications as a marker of increased cardiovascular risk: A meta-analysis. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2009, 5, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leow, K.; Szulc, P.; Schousboe, J.T.; Kiel, D.P.; Teixeira-Pinto, A.; Shaikh, H.; Sawang, M.; Sim, M.; Bondonno, N.; Hodgson, J.M.; et al. Prognostic Value of Abdominal Aortic Calcification: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e017205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rantasalo, V.; Laukka, D.; Nikulainen, V.; Jalkanen, J.; Gunn, J.; Hakovirta, H. Aortic calcification index predicts mortality and cardiovascular events in operatively treated patients with peripheral artery disease: A prospective PURE ASO cohort follow-up study. J. Vasc. Surg. 2022, 76, 1657–1666.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, C.; Liu, I.; El Khoury, R.; Zhou, B.; Braun, H.; Conte, M.S.; Hiramoto, J. Iliac artery calcification score stratifies mortality risk estimation in patients with chronic limb-threatening ischemia undergoing revascularization. J. Vasc. Surg. 2023, 78, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P.; Chetan, M.R.; Tapping, C.R.; Lintin, L. Measurement of Aortic Atherosclerotic Disease Severity: A Novel Tool for Simplified, Objective Disease Scoring Using CT Angiography. Cureus 2021, 13, e15561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, B.; Marin, D.; Hurwitz, L.M.; Ronald, J.; Ellis, M.J.; Ravindra, K.V.; Collins, B.H.; Kim, C.Y. Application of a Novel CT-Based Iliac Artery Calcification Scoring System for Predicting Renal Transplant Outcomes. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2016, 206, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornasari, A.; Kuntz, S.; Martini, C.; Perini, P.; Cabrini, E.; Freyrie, A.; Lejay, A.; Chakfé, N. Objective Methods to Assess Aorto-Iliac Calcifications: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauppila, L.I.; Polak, J.F.; Cupples, L.A.; Hannan, M.T.; Kiel, D.P.; Wilson, P.W. New indices to classify location, severity and progression of calcific lesions in the abdominal aorta: A 25-year follow-up study. Atherosclerosis 1997, 132, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schousboe, J.T.; Wilson, K.E.; Kiel, D.P. Detection of abdominal aortic calcification with lateral spine imaging using DXA. J. Clin. Densitom. 2006, 9, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NasrAllah, M.M.; Nassef, A.; Elshaboni, T.H.; Morise, F.; Osman, N.A.; Sharaf El Din, U.A. Comparing different calcification scores to detect outcomes in chronic kidney disease patients with vascular calcification. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 220, 884–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goorani, S.; Zangene, S.; Imig, J.D. Hypertension: A continuing public healthcare issue. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 26, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolters, F.J.; Chibnik, L.B.; Waziry, R.; Anderson, R.; Berr, C.; Beiser, A.; Bis, J.C.; Blacker, D.; Bos, D.; Brayne, C.; et al. Twenty-seven-year time trends in dementia incidence in Europe and the United States: The Alzheimer Cohorts Consortium. Neurology 2020, 95, e519–e531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikbov, B.; Purcell, C.A.; Levey, A.S.; Smith, M.; Abdoli, A.; Abebe, M.; Adebayo, O.M.; Afarideh, M.; Agarwal, S.K.; Agudelo-Botero, M.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2020, 395, 709–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons-Bell, S.; Johnson, C.; Roth, G. Prevalence, incidence and survival of heart failure: A systematic review. Heart 2022, 108, 1351–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khurshid, S.; Ashburner, J.M.; Ellinor, P.T.; McManus, D.D.; Atlas, S.J.; Singer, D.E.; Lubitz, S.A. Prevalence and Incidence of Atrial Fibrillation Among Older Primary Care Patients. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2255838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salari, N.; Darvishi, N.; Bartina, Y.; Larti, M.; Kiaei, A.; Hemmati, M.; Shohaimi, S.; Mohammadi, M. Global prevalence of osteoporosis among the world older adults: A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2021, 16, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, S.S.; Gustin, W.; Wong, N.D.; Larson, M.G.; Weber, M.A.; Kannel, W.B.; Levy, D. Hemodynamic patterns of age-related changes in blood pressure. The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 1997, 96, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, R.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, M.; Piao, H.; Gu, Z.; Zhu, C. Associations between bone mineral density and abdominal aortic calcification: Results of a nationwide survey. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2024, 34, 1488–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Huang, D.; Zhang, Y. The bone-vascular axis: The link between osteoporosis and vascular calcification. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2025, 480, 3413–3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siracusa, C.; Carabetta, N.; Morano, M.B.; Manica, M.; Strangio, A.; Sabatino, J.; Leo, I.; Castagna, A.; Cianflone, E.; Torella, D.; et al. Understanding Vascular Calcification in Chronic Kidney Disease: Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Zheng, L.; Xu, H.; Tang, D.; Lin, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, C.; Wang, W.; Yuan, Q.; Tao, L.; et al. Oxidative stress contributes to vascular calcification in patients with chronic kidney disease. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2020, 138, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, P.; DeRiso, A.; Patel, M.; Battepati, D.; Khatib-Shahidi, B.; Sharma, H.; Gupta, R.; Malhotra, D.; Dworkin, L.; Haller, S.; et al. Vascular Calcification in Chronic Kidney Disease: Diversity in the Vessel Wall. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaccarino, R.; Abdulrasak, M.; Resch, T.; Edsfeldt, A.; Sonesson, B.; Dias, N.V. Low Iliofemoral Calcium Score May Predict Higher Survival after EVAR and FEVAR. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2020, 68, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendriks, E.J.; Beulens, J.W.; de Jong, P.A.; van der Schouw, Y.T.; Sun, W.-N.; Wright, C.M.; Criqui, M.H.; Allison, M.A.; Ix, J.H. Calcification of the splenic, iliac, and breast arteries and risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Atherosclerosis 2017, 259, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, C.; Cai, Z.; Yang, P. Association of the abdominal aortic calcification with all-cause and cardiovascular disease-specific mortality: Prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0314776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cohort n = 224 | 65–74 n = 77 | 75–84 n = 79 | ≥85 n = 68 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age—years | 78.8 (8.5) | 69.2 (2.9) | 79.5 (2.9) | 89.0 (3.3) | |

| Sex—Female | 139 (62.1) | 39 (50.6) | 45 (57.0) | 55 (80.9) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 121 (54.0) | 27 (35.1) | 51 (64.6) | 43 (63.2) | <0.001 |

| Osteoporosis | 81 (36.2) | 15 (19.5) | 25 (31.6) | 41 (50.6) | <0.001 |

| CAD | 52 (23.2) | 13 (16.9) | 20 (25.3) | 19 (27.9) | 0.249 |

| AF | 47 (21.0) | 10 (13.0) | 15 (19.0) | 22 (32.4) | 0.015 |

| CHF | 29 (12.9) | 4 (5.2) | 9 (11.4) | 16 (23.5) | 0.004 |

| Stroke/TIA | 27 (12.1) | 5 (6.5) | 9 (11.4) | 13 (19.1) | 0.065 |

| CKD | 26 (11.6) | 3 (3.9) | 6 (7.6) | 17 (25.0) | <0.001 |

| NCD | 26 (11.6) | 2 (2.6) | 5 (6.3) | 19 (27.9) | <0.001 |

| DM | 19 (8.5) | 4 (5.2) | 9 (11.4) | 6 (8.8) | 0.378 |

| Antiplatelet therapy | 77 (34.4) | 21 (27.3) | 29 (36.7) | 27 (39.7) | 0.25 |

| Anticoagulant therapy | 54 (24.1) | 8 (10.4) | 23 (29.1) | 23 (33.8) | 0.002 |

| Cohort n = 224 | 65–74 n = 77 | 75–84 n = 79 | ≥85 n = 68 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AACS | <0.001 | ||||

| 70 (31.3) | 39 (50.6) | 24 (30.4) | 7 (10.3) | |

| 53 (23.7) | 16 (20.8) | 20 (25.3) | 17 (25.0) | |

| 101 (45.1) | 22 (28.6) | 35 (44.3) | 44 (64.7) | |

| CIACS | <0.001 | ||||

| 51 (22.8) | 27 (35.1) | 17 (21.5) | 7 (10.3) | |

| 95 (42.4) | 36 (46.8) | 33 (41.8) | 26 (38.2) | |

| 78 (34.8) | 14 (18.2) | 29 (36.7) | 35 (51.5) | |

| EIACS | 0.006 | ||||

| 165 (73.7) | 66 (85.7) | 59 (74.7) | 40 (58.8) | |

| 34 (15.2) | 8 (10.4) | 11 (13.9) | 15 (22.1) | |

| 25 (11.2) | 3 (3.9) | 9 (11.4) | 13 (19.1) | |

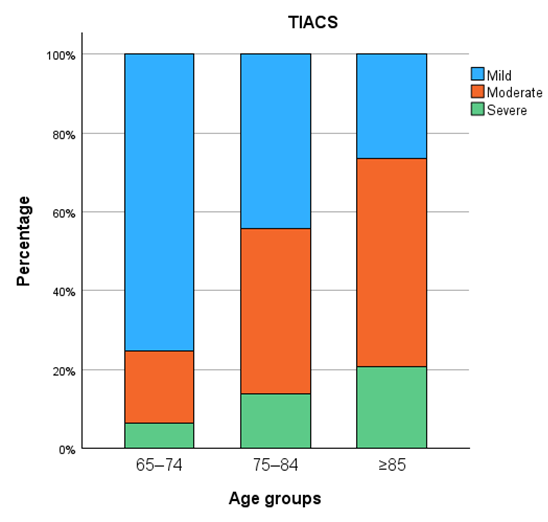

| TIACS | <0.001 | ||||

| 111 (49.6) | 58 (75.3) | 35 (44.3) | 18 (26.5) | |

| 83 (37.1) | 14 (18.2) | 33 (41.8) | 36 (52.9) | |

| 30 (13.4) | 5 (6.5) | 11 (13.9) | 14 (20.6) |

| χ2 (df = 4) | p-Value | Cramer’s V | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AACS and CIACS | 128.3 | <0.001 | 0.535 |

| AACS and EIACS | 38.35 | <0.001 | 0.293 |

| AACS and TIACS | 101.26 | <0.001 | 0.475 |

| CIACS and EIACS | 81.29 | <0.001 | 0.426 |

| CIACS and TIACS | 151.89 | <0.001 | 0.582 |

| EIACS and TIACS | 216.66 | <0.001 | 0.695 |

| Variables | B | SE | β | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.074 | 0.016 | 0.323 | 0.042–0.106 | <0.001 |

| Sex (male) | 0.199 | 0.266 | 0.049 | −0.325–0.723 | 0.455 |

| Hypertension | −0.029 | 0.248 | −0.008 | −0.518–0.459 | 0.905 |

| Osteoporosis | 0.488 | 0.278 | 0.120 | −0.059–1.036 | 0.080 |

| CHF | −0.214 | 0.362 | −0.037 | −0.928–0.500 | 0.556 |

| CKD | 1.004 | 0.387 | 0.164 | 0.242–1.766 | 0.010 |

| NCD | 0.294 | 0.394 | 0.048 | −0.482–1.070 | 0.456 |

| Antiplatelet therapy | 0.587 | 0.253 | 0.142 | 0.089–1.086 | 0.021 |

| Variables | B | SE | β | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.126 | 0.025 | 0.358 | 0.077–0.175 | <0.001 |

| Sex (male) | 0.200 | 0.410 | 0.032 | −0.607–1.008 | 0.625 |

| Hypertension | −0.395 | 0.382 | −0.066 | −1.149–0.358 | 0.302 |

| Osteoporosis | 0.569 | 0.428 | 0.091 | −0.275–1.413 | 0.185 |

| CHF | 0.225 | 0.559 | 0.025 | −0.876–1.326 | 0.687 |

| CKD | 0.930 | 0.596 | 0.100 | −0.244–2.105 | 0.120 |

| NCD | 0.323 | 0.607 | 0.035 | −0.874–1.520 | 0.595 |

| Antiplatelet therapy | 0.899 | 0.390 | 0.143 | 0.130–1.668 | 0.022 |

| Variables | B | SE | β | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.123 | 0.026 | 0.332 | 0.071–0.174 | <0.001 |

| Sex (male) | 0.451 | 0.428 | 0.069 | −0.393–1.294 | 0.293 |

| Hypertension | −0.400 | 0.399 | −0.063 | −1.186–0.386 | 0.318 |

| Osteoporosis | 0.095 | 0.447 | 0.015 | −0.786–0.976 | 0.831 |

| CHF | 1.764 | 0.583 | 0.188 | 0.615–2.913 | 0.003 |

| CKD | 0.559 | 0.622 | 0.057 | −0.667–1.785 | 0.370 |

| NCD | 0.648 | 0.634 | 0.066 | −0.601–1.898 | 0.307 |

| Antiplatelet therapy | 1.128 | 0.407 | 0.170 | 0.326–1.931 | 0.006 |

| Variables | B | SE | β | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.124 | 0.023 | 0.376 | 0.079–0.170 | <0.001 |

| Sex (male) | 0.326 | 0.376 | 0.056 | −0.415–1.066 | 0.387 |

| Hypertension | −0.397 | 0.350 | −0.070 | −1.088–0.293 | 0.258 |

| Osteoporosis | 0.332 | 0.392 | 0.057 | −0.441–1.106 | 0.398 |

| CHF | 0.995 | 0.512 | 0.119 | −0.015–2.004 | 0.053 |

| CKD | 0.745 | 0.546 | 0.085 | −0.332–1.822 | 0.174 |

| NCD | 0.486 | 0.557 | 0.055 | −0.611–1.583 | 0.384 |

| Antiplatelet therapy | 1.014 | 0.358 | 0.171 | 0.309–1.719 | 0.005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lutz, M.; Galijasevic, M.; Lindtner, R.A.; Ellmerer, A.E.; Wippel, D.; Gizewski, E.R.; Mangesius, S.; Krappinger, D.; Loizides, A. Vascular Calcification Patterns in the Elderly: Correlation Between Aortic and Iliac Calcification Burden. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3151. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243151

Lutz M, Galijasevic M, Lindtner RA, Ellmerer AE, Wippel D, Gizewski ER, Mangesius S, Krappinger D, Loizides A. Vascular Calcification Patterns in the Elderly: Correlation Between Aortic and Iliac Calcification Burden. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3151. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243151

Chicago/Turabian StyleLutz, Maximilian, Malik Galijasevic, Richard A. Lindtner, Andreas E. Ellmerer, David Wippel, Elke R. Gizewski, Stephanie Mangesius, Dietmar Krappinger, and Alexander Loizides. 2025. "Vascular Calcification Patterns in the Elderly: Correlation Between Aortic and Iliac Calcification Burden" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3151. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243151

APA StyleLutz, M., Galijasevic, M., Lindtner, R. A., Ellmerer, A. E., Wippel, D., Gizewski, E. R., Mangesius, S., Krappinger, D., & Loizides, A. (2025). Vascular Calcification Patterns in the Elderly: Correlation Between Aortic and Iliac Calcification Burden. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3151. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243151