Diffusion-Weighted MRI as a Non-Invasive Diagnostic Tool for Ascites Characterization: A Comparative Analysis of Mean and Minimum ADC Values Against the Serum-Ascites Albumin Gradient

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Population

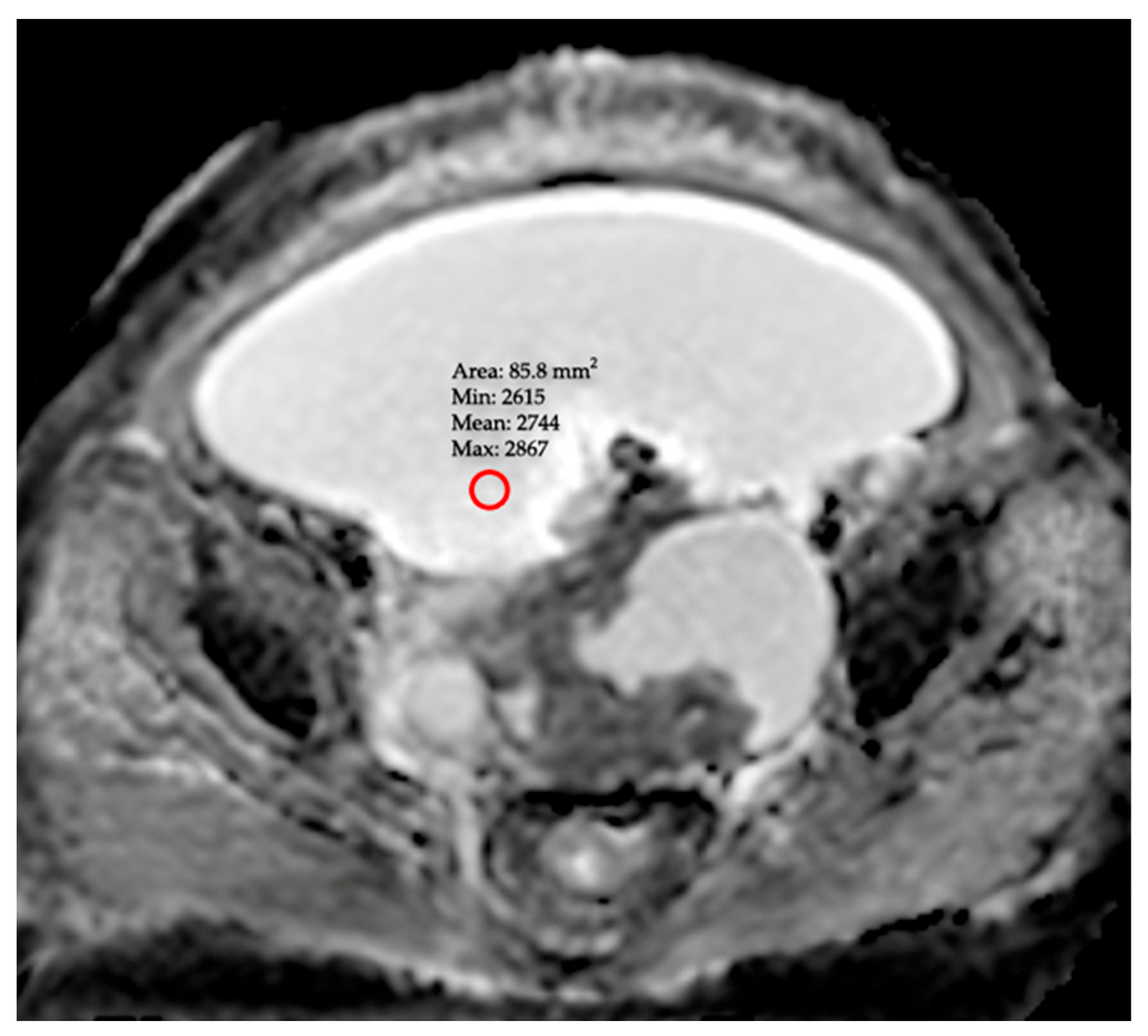

2.2. MRI Protocol and Radiologic Evaluation

- •

- ADCmean (Mean ADC): The arithmetic mean of the ADC values obtained from the three distinct ROIs.

- •

- ADCmin (Minimum ADC): A value obtained from a single ROI placed on the area exhibiting the lowest signal intensity (appearing darkest) on the ADC map, following a meticulous inspection of the entire peritoneal cavity. To prevent this measurement from being subjective, observers used standard window settings (window width/level). This approach is predicated on the hypothesis that it may reflect the most aggressive component of the pathology by specifically targeting the region of highest focal malignancy or greatest fluid viscosity.

- •

- Inter-observer agreement was also calculated to determine the reliability of these measurements.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

3.2. Laboratory Findings

3.3. Inter-Observer Agreement

3.4. Diagnostic Performance Analysis of ADC Values

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, Y.-Y.; Peng, X.-L.; Zhan, N.; Tian, S.; Li, J.; Dong, W.-G. Development and validation a simple model for identify malignant ascites. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 18, 1966–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikegami, T.; Ishiki, H.; Kadono, T.; Ito, T.; Yokomichi, N. Narrative review of malignant ascites: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, assessment, and treatment. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2024, 13, 842–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, D.K.; Gupta, P.; Neelam, P.B.; Kumar, R.; Krishnaraju, V.S.; Rohilla, M.; Prasad, A.S.; Dutta, U.; Sharma, V. Clinical and Radiological Parameters to Discriminate Tuberculous Peritonitis and Peritoneal Carcinomatosis. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.-L.; Xia, H.H.-X.; Zhu, S.-L. Ascitic Fluid Analysis in the Differential Diagnosis of Ascites: Focus on Cirrhotic Ascites. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2014, 2, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baliyan, V.; Das, C.J.; Sharma, R.; Gupta, A.K. Diffusion weighted imaging: Technique and applications. World J. Radiol. 2016, 8, 785–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenoy-Bhangle, A.; Baliyan, V.; Kordbacheh, H.; Guimaraes, A.R.; Kambadakone, A. Diffusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging of liver: Principles, clinical applications and recent updates. World J. Hepatol. 2017, 9, 1081–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kele, P.; van Jagt, E.J. Diffusion weighted imaging in the liver. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 1567–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Bonekamp, S.; Kamel, I. Diffusion-Weighted Imaging in Abdominal Oncology. Curr. Med. Imaging 2012, 8, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilickesmez, O.; Bayramoglu, S.; Inci, E.; Cimilli, T. Value of apparent diffusion coefficient measurement for discrimination of focal benign and malignant hepatic masses. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 2009, 53, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gity, M.; Moradi, B.; Arami, R.; Kheradmand, A.; Kazemi, M.A. Two Different Methods of Region-of-Interest Placement for Differentiation of Benign and Malignant Breast Lesions by Apparent Diffusion Coefficient Value. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. APJCP 2018, 19, 2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scepanovic, B.; Andjelic, N.; Mladenovic-Segedi, L.; Kozic, D.; Vuleta, D.; Molnar, U.; Nikolic, O. Diagnostic value of the apparent diffusion coefficient in differentiating malignant from benign endometrial lesions. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1109495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erol, S.; Dertli, R.; Asil, M.; Boyraz, Y.K.; Kerimoglu, U. Magnetic Resonance Enterography Findings and Correlation of Apparent Diffusion Coefficient Values with Clinical Response in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients. Selcuk Tip Derg. 2021, 1, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baysal, T.; Bulut, T.; Gökirmak, M.; Kalkan, S.; Dusak, A.; Dogan, M. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging of pleural fluid: Differentiation of transudative vs exudative pleural effusions. Eur. Radiol. 2004, 14, 890–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin, Z.; Yeşildağ, M.; Alkan, E.; Kayhan, A.; Tolu, I.; Keskin, S. Differentiation between transudative and exudative pleural effusions by diffusionweighted magnetic resonance imaging. Iran. J. Radiol. 2019, 16, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inan, N.; Arslan, A.; Akansel, G.; Arslan, Z.; Elemen, L.; Eleman, L.; Demirci, A. Diffusion-weighted MRI in the characterization of pleural effusions. Diagn. Interv. Radiol. 2009, 15, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, D.-M.; Collins, D.J. Diffusion-weighted MRI in the body: Applications and challenges in oncology. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2007, 188, 1622–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratkoceri Hasi, G.; Osredkar, J.; Jerin, A. The Diagnostic Role of Tumor and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Ascitic Fluid: A Systematic Review. Medicina 2025, 61, 1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ștefan, P.-A.; Csutak, C.; Lebovici, A.; Rusu, G.M.; Mihu, C.M. Diffusion-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging as a Noninvasive Parameter for Differentiating Benign and Malignant Intraperitoneal Collections. Medicina 2020, 56, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karoo, R.O.S.; Lloyd, T.D.R.; Garcea, G.; Redway, H.D.; Robertson, G.S.R. How valuable is ascitic cytology in the detection and management of malignancy? Postgrad. Med. J. 2003, 79, 292–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Runyon, B.A.; Hoefs, J.C.; Morgan, T.R. Ascitic fluid analysis in malignancy-related ascites. Hepatology 1988, 8, 1104–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermoolen, M.A.; Kwee, T.C.; Nievelstein, R.A.J. Apparent diffusion coefficient measurements in the differentiation between benign and malignant lesions: A systematic review. Insights Into Imaging 2012, 3, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Runyon, B.A. Refractory ascites. Semin. Liver Dis. 1993, 13, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMullen, J.R.W.; Selleck, M.; Wall, N.R.; Senthil, M. Peritoneal carcinomatosis: Limits of diagnosis and the case for liquid biopsy. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 43481–43490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doshi, A.M.; Campbell, N.; Hajdu, C.H.; Rosenkrantz, A.B. Differentiation of Malignant Omental Caking from Benign Omental Thickening using MRI. Abdom. Imaging 2015, 40, 1157–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group 1: Benign (n = 85) | Group 2: Malignant (n = 65) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year, mean ± SD) | 66.2 ± 6.9 | 64.0 ± 6.0 | 0.094 |

| Gender (Female, n [%]) | 37 (48.2%) | 33 (56.9%) | 0.378 |

| Primary Etiology (n [%]) | |||

| Group 1: Benign (n = 85) | Group 2: Malignant (n = 65) | ||

| Liver cirrhosis | 46 (54.1%) | Ovarian cancer | 27 (41.5%) |

| Congestive heart failure | 16 (18.8%) | Gastric cancer | 13 (20%) |

| Pancreatitis | 10 (11.7%) | Colorectal cancer | 13 (20%) |

| Nephrogenic ascites | 10 (11.7%) | Pancreatic cancer | 6 (9.2%) |

| Peritoneal Tuberculosis | 2 (2.3%) | Cervical cancer | 4 (6.1%) |

| Budd-Chiari Syndrome | 1 (1.1%) | Primary peritoneal carcinomatosis | 2 (3%) |

| Parameter (Mean ± SD) | Group 1: Benign (n = 85) | Group 2: Malignant (n = 65) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum Albumin (g/dL) | 3.01 ± 0.32 | 3.15 ± 0.28 | 0.14 |

| Ascites Albumin (g/dL) | 1.49 ± 0.35 | 2.71 ± 0.41 | <0.001 |

| SAAG (g/dL) | 1.40 ± 0.30 | 0.72 ± 0.34 | <0.001 |

| Serum LDH (U/L) | 207.07 ± 28.9 | 404 ± 77.7 | <0.001 |

| Ascites LDH (U/L) | 112.2 ± 21.1 | 504.3 ± 77 | <0.001 |

| Serum Glucose (mg/dL) | 110.5 ± 13.0 | 120.4 ± 9.6 | 0.08 |

| Ascites Glucose (mg/dL) | 107.1 ± 12.4 | 69.9 ± 5.9 | <0.001 |

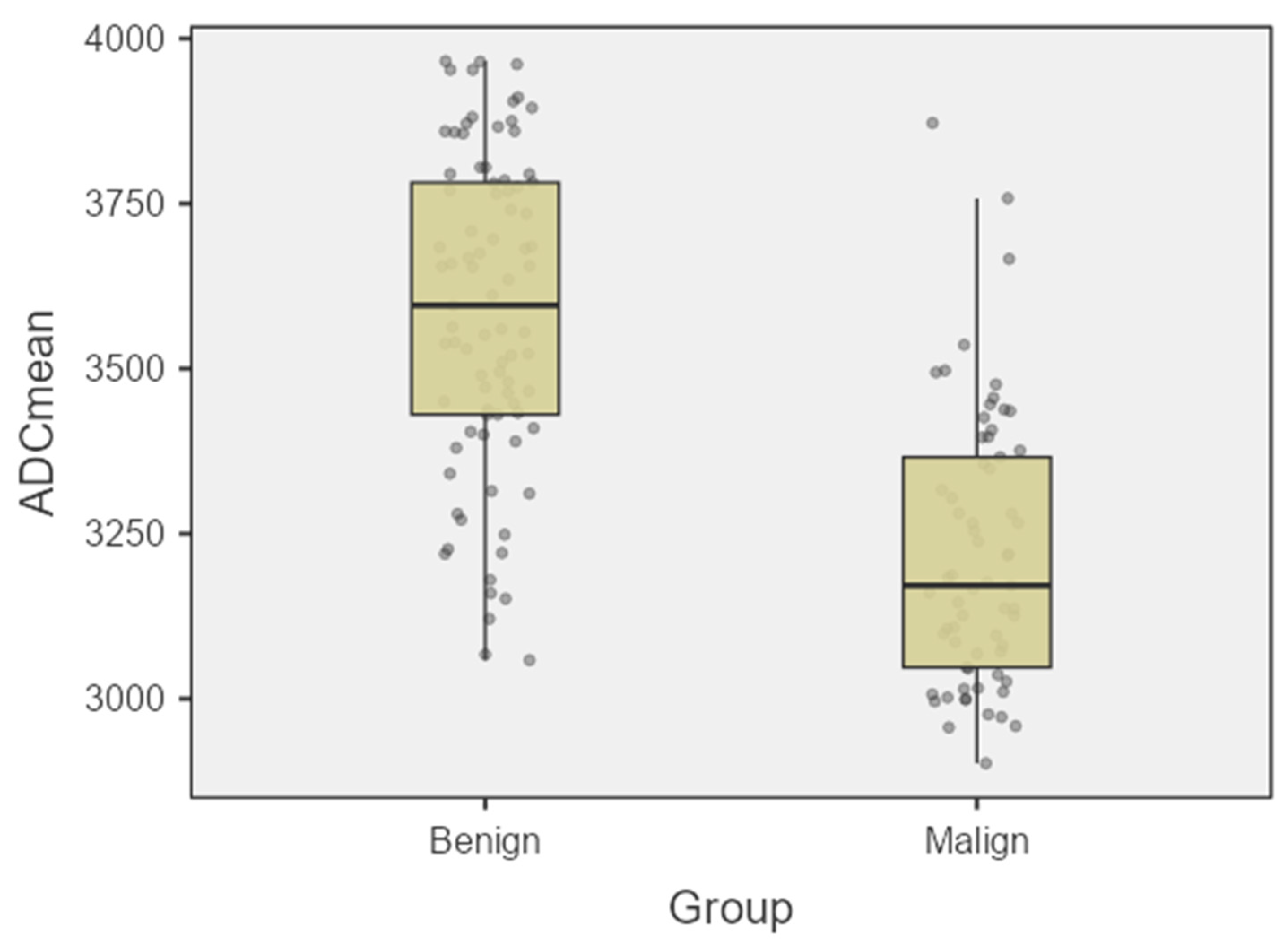

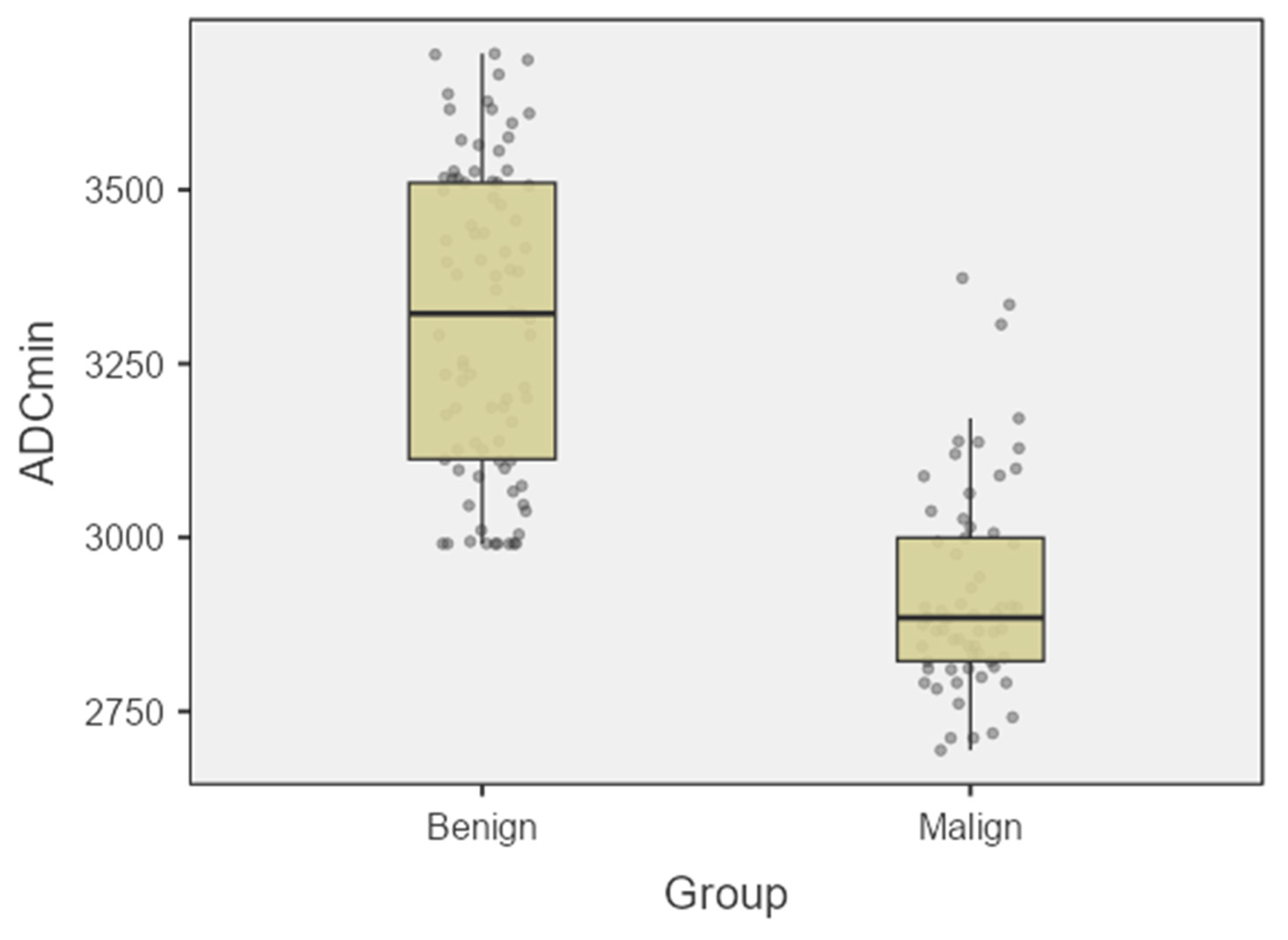

| (×10−6 mm2/s) | Group 1: Benign (n = 85) | Group 2: Malignant (n = 65) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADCmean | 3596 ± 239 | 3162 ± 204 | 0.006 |

| ADCmin | 3322 ± 218 | 2885 ± 148 | 0.0016 |

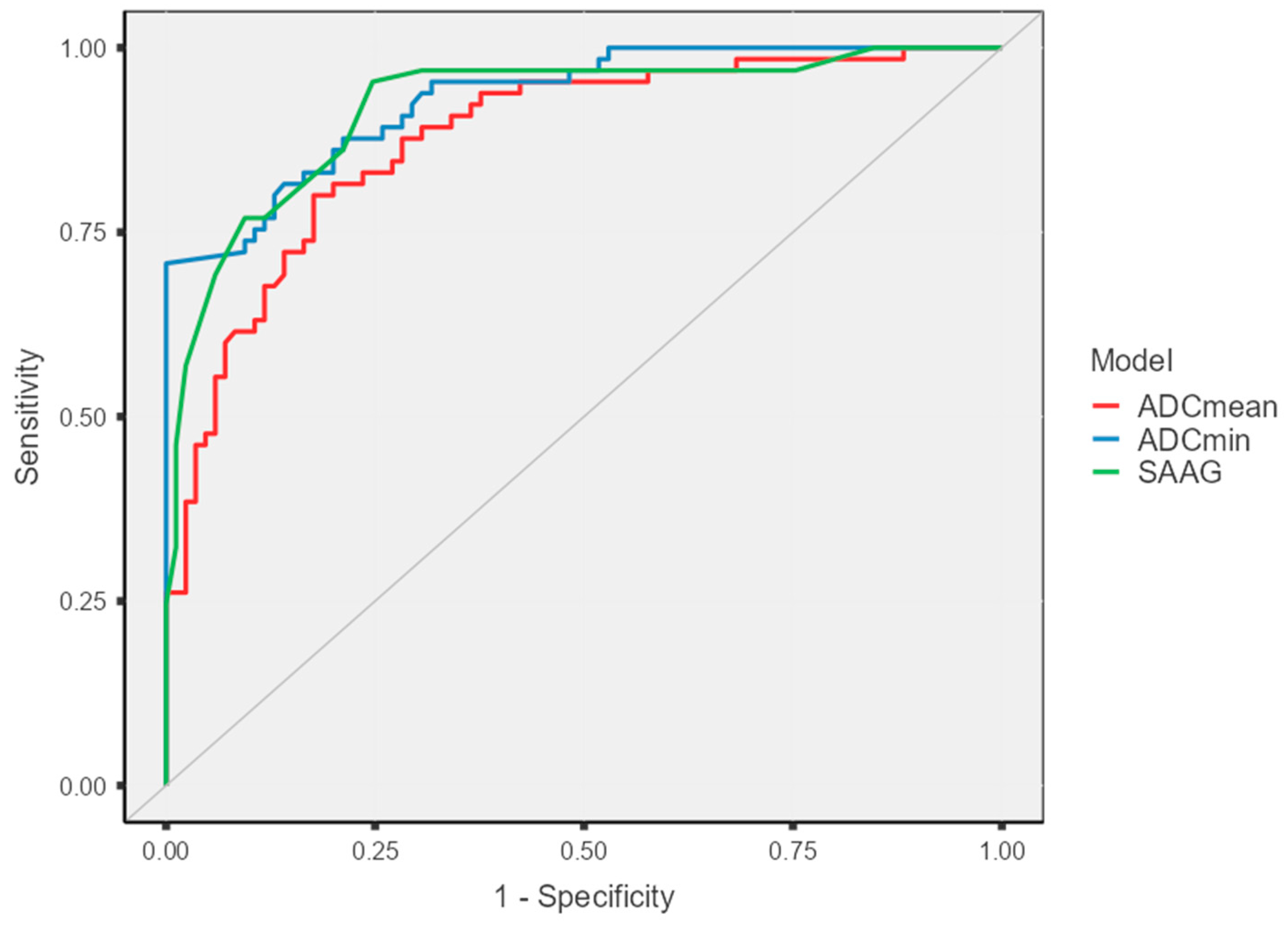

| Parameter | AUC (95% CI) | Optimal Cut-Off | Sensitivity (%) [95% CI] | Specificity (%) [95% CI] | PPV (%) [95% CI] | NPV (%) [95% CI] | Youden’s Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADCmean | 0.877 (0.822–0.932) | 3378 × 10−6 mm2/s | 80 [68.2–88.9] | 82.3 [72.5–89.7] | 77.6 [68.3–84.7] | 84.3 [76.6–89.8] | 0.62 |

| ADCmin | 0.930 (0.892–0.968) | 2983 × 10−6 mm2/s | 81.5 [74.4–86.9] | 85.8 [75.9–90.2] | 81.5 [75.4–86.7] | 85.8 [80.1–89.9] | 0.67 |

| SAAG | 0.919 (0.874–0.965) | 1.25 g/dL | 72.2 [64.7–84.0] | 92.3 [83.7–95.8] | 95.5 [87.5–98.4] | 74.7 [66.9–81.1] | 0.64 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ataş, A.E.; Ünüvar, Ş.; Eryeşil, H.; Kökbudak, N. Diffusion-Weighted MRI as a Non-Invasive Diagnostic Tool for Ascites Characterization: A Comparative Analysis of Mean and Minimum ADC Values Against the Serum-Ascites Albumin Gradient. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3130. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243130

Ataş AE, Ünüvar Ş, Eryeşil H, Kökbudak N. Diffusion-Weighted MRI as a Non-Invasive Diagnostic Tool for Ascites Characterization: A Comparative Analysis of Mean and Minimum ADC Values Against the Serum-Ascites Albumin Gradient. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3130. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243130

Chicago/Turabian StyleAtaş, Abdullah Enes, Şeyma Ünüvar, Hasan Eryeşil, and Naile Kökbudak. 2025. "Diffusion-Weighted MRI as a Non-Invasive Diagnostic Tool for Ascites Characterization: A Comparative Analysis of Mean and Minimum ADC Values Against the Serum-Ascites Albumin Gradient" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3130. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243130

APA StyleAtaş, A. E., Ünüvar, Ş., Eryeşil, H., & Kökbudak, N. (2025). Diffusion-Weighted MRI as a Non-Invasive Diagnostic Tool for Ascites Characterization: A Comparative Analysis of Mean and Minimum ADC Values Against the Serum-Ascites Albumin Gradient. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3130. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243130