The Correlation Between Lateral Ventricle Asymmetry and Cerebral Blood Flow: Implications for Stroke Risk

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

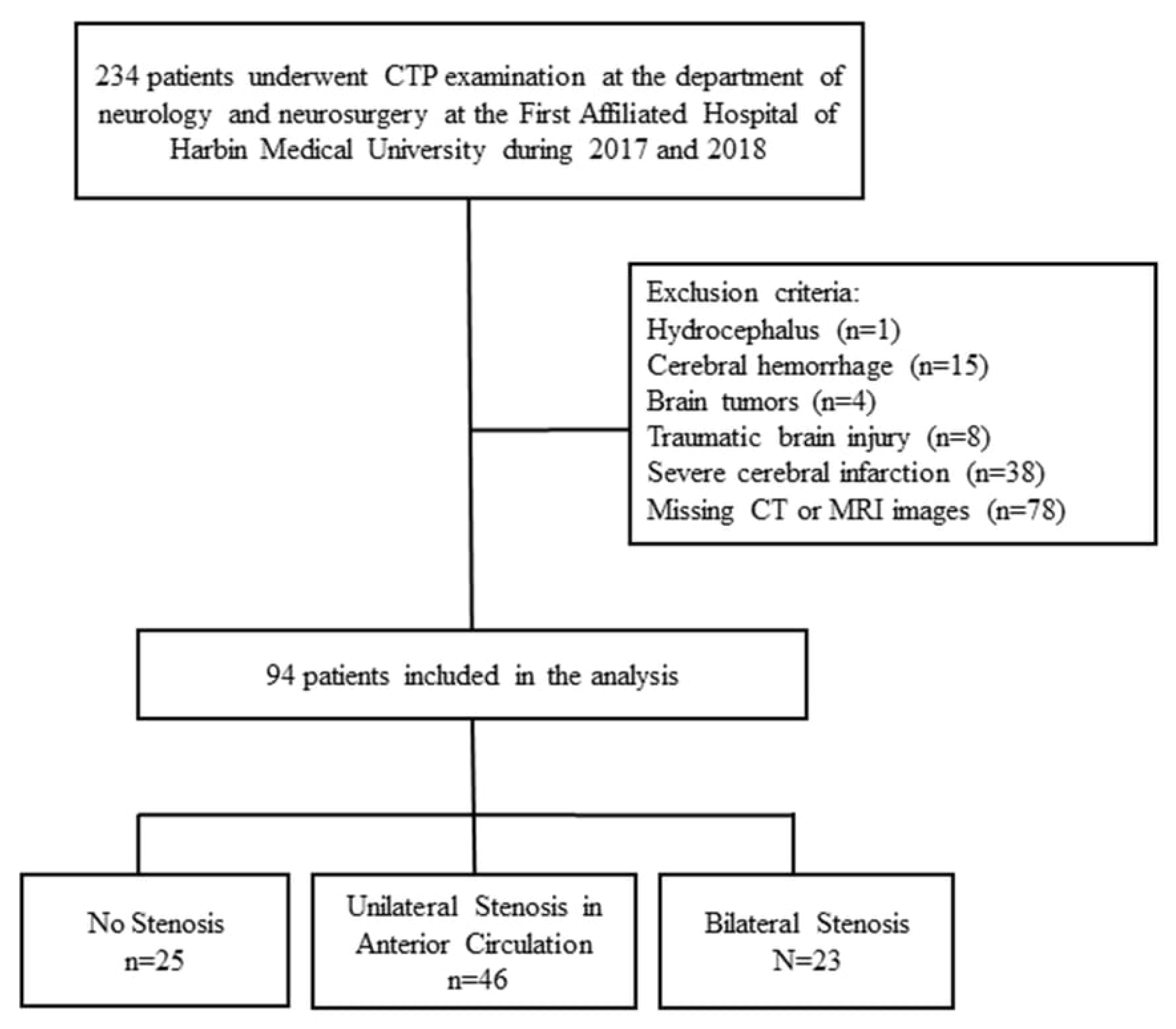

2.1. Subjects

- (1)

- For participants who were re-admitted to our hospital during the follow-up period, stroke status was determined by reviewing electronic medical records according to the diagnostic criteria described above, as confirmed by review of the electronic medical records, including discharge summaries and neuroimaging reports.

- (2)

- For participants who did not return to our hospital, stroke status was determined through structured telephone interviews. A stroke event was recorded only when the participant or a family member confirmed that the event had been diagnosed by a licensed physician and that the episode required emergency evaluation or hospitalization.

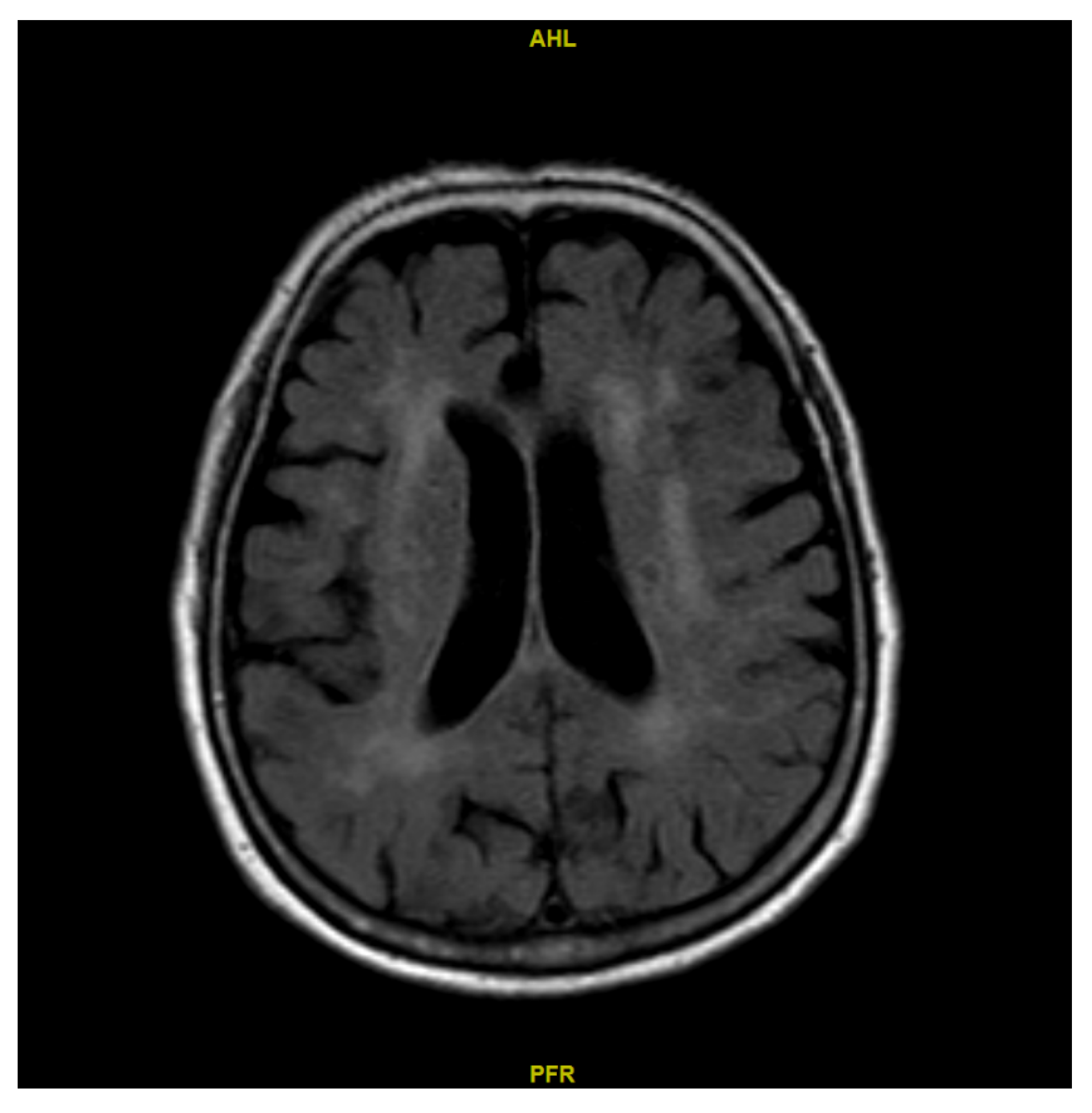

2.2. Determination of the Lateral Ventricle Volume of Both Sides

2.3. Determination of CBF

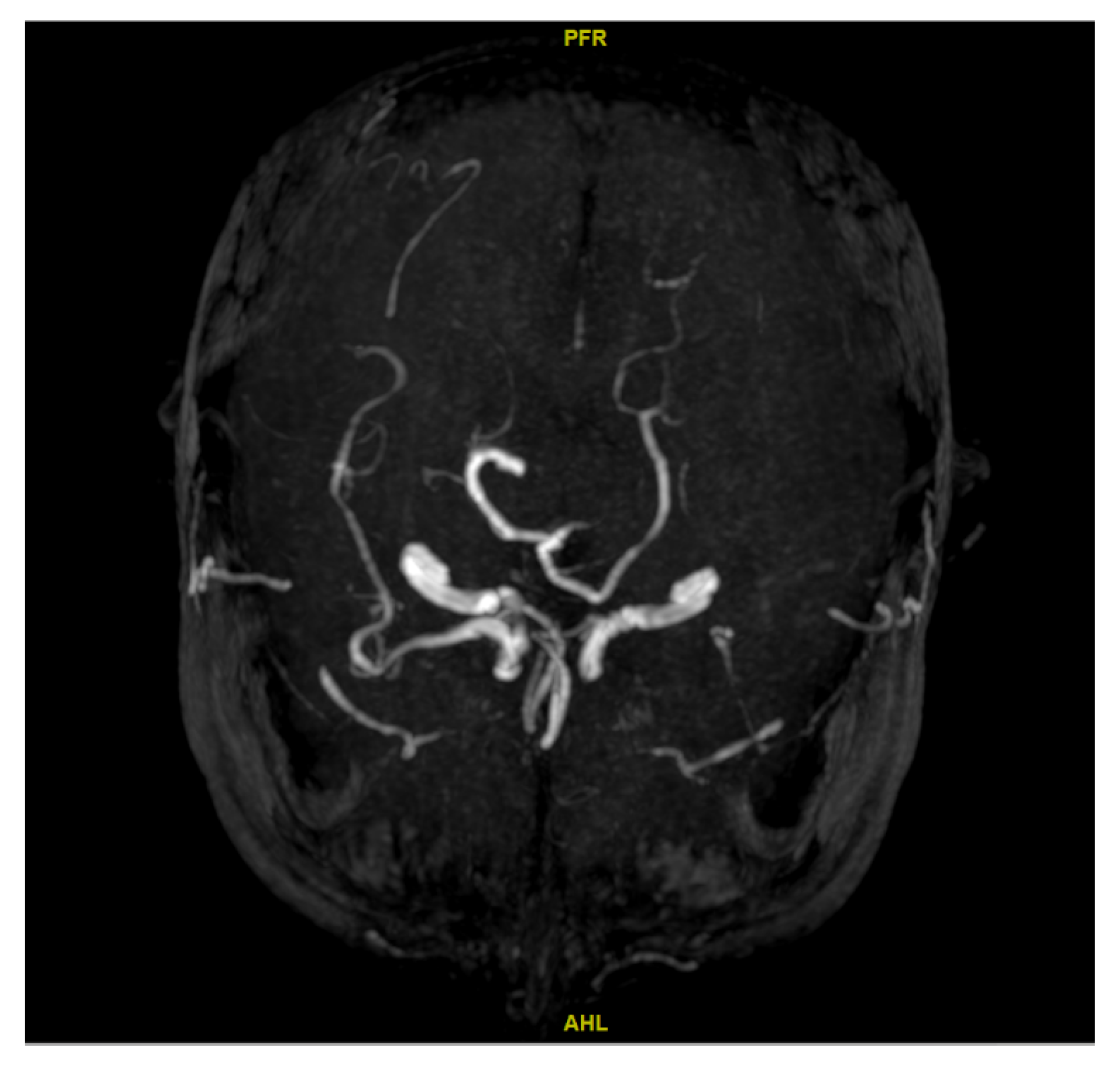

2.4. Ascertainment of Cerebral Artery Stenosis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patients’ Characteristics

3.2. Comparison Between CBF on the Side of the LLV and the Side of the SLV Across the ROIs

3.3. Relative CBF Between the LLV and SLV Sides Across the ROIs in Patients with and Without Unilateral Stenosis

3.4. Correlation Between the Lateral Ventricle Volume Difference and Relative CBF Across the ROIs

3.5. Associations Between the Lateral Ventricle Volume Difference, Relative CBF Across ROIs, and Presence of Stenosis

3.6. Associations Between the Lateral Ventricle Volume Difference, Relative CBF Across ROIs, and Stroke During Follow-Up

4. Discussion

Strength and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Fang, Y.; Xia, J.; Lian, Y.; Zhang, M.; Kang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, L.; Yin, P.; Wang, Z.; Ye, C.; et al. The burden of cardiovascular disease attributable to dietary risk factors in the provinces of China, 2002–2018: A nationwide population-based study. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2023, 37, 100784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Yin, P.; Wang, L.; Qi, J.; You, J.; Lin, L.; Meng, S.; Wang, F.; et al. Mortality and years of life lost of cardiovascular diseases in China, 2005-2020: Empirical evidence from national mortality surveillance system. Int. J. Cardiol. 2021, 340, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsao, C.W.; Aday, A.W.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Anderson, C.A.; Arora, P.; Avery, C.L.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Beaton, A.Z.; Boehme, A.K.; Buxton, A.E.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2023 Update: A Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023, 147, e93–e621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leng, X.; Wong, K.S.; Liebeskind, D.S. Evaluating intracranial atherosclerosis rather than intracranial stenosis. Stroke 2014, 45, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabarudin, A.; Subramaniam, C.; Sun, Z. Cerebral CT angiography and CT perfusion in acute stroke detection: A systematic review of diagnostic value. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2014, 4, 282–290. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wu, X.; Degnan, A.J.; Malhotra, A.; Zhu, C. Culprit intracranial plaque without substantial stenosis in acute ischemic stroke on vessel wall MRI: A systematic review. Atherosclerosis 2019, 287, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Lee, S.J.; Hong, J.M.; Alverne, F.J.A.M.; Lima, F.O.; Nogueira, R.G. Endovascular Treatment of Large Vessel Occlusion Strokes Due to Intracranial Atherosclerotic Disease. J. Stroke 2022, 24, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Wei, Y. Neuronal injuries in cerebral infarction and ischemic stroke: From mechanisms to treatment (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2021, 49, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, K.; Sakoda, S. Mechanism underlying thrombus formation in cerebral infarction. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 2009, 49, 798–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Maniar, S.; Manole, M.D.; Sun, D. Cerebral Hypoperfusion and Other Shared Brain Pathologies in Ischemic Stroke and Alzheimer’s Disease. Transl. Stroke Res. 2018, 9, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asada, Y.; Yamashita, A.; Sato, Y.; Hatakeyama, K. Thrombus Formation and Propagation in the Onset of Cardiovascular Events. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2018, 25, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claassen, J.A.H.R.; Thijssen, D.H.J.; Panerai, R.B.; Faraci, F.M. Regulation of cerebral blood flow in humans: Physiology and clinical implications of autoregulation. Physiol. Rev. 2021, 101, 1487–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ban, M.; Han, X.; Bao, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, P. Evaluation of collateral status and outcome in patients with middle cerebral artery stenosis in late time window by CT perfusion imaging. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 991023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiroğlu, Y.; Karabulut, N.; Oncel, C.; Yagci, B.; Sabir, N.; Ozdemir, B. Cerebral lateral ventricular asymmetry on CT: How much asymmetry is representing pathology? Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2008, 30, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scelsi, C.L.; Rahim, T.A.; Morris, J.A.; Kramer, G.; Gilbert, B.; Forseen, S. The Lateral Ventricles: A Detailed Review of Anatomy, Development, and Anatomic Variations. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2020, 41, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.M.; Smith, A.B.; Styner, M.; Gu, H.; Poole, R.; Zhu, H.; Li, Y.; Barbero, X.; Gouttard, S.; McKeown, M.J.; et al. Asymmetrical lateral ventricular enlargement in Parkinson’s disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 2009, 16, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubben, N.; Ensink, E.; Coetzee, G.A.; Labrie, V. The enigma and implications of brain hemispheric asymmetry in neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Commun. 2021, 3, fcab211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; He, J.; Yu, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, Z.; Gong, J. Measurement of lateral ventricle volume of normal infant based on magnetic resonance imaging. Chin. Neurosurg. J. 2019, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, J.; Heinze, M.; Günther, M.; Cheng, B.; Nickel, A.; Schröder, T.; Fischer, F.; Kessner, S.S.; Magnus, T.; Fiehler, J.; et al. Dynamics of brain perfusion and cognitive performance in revascularization of carotid artery stenosis. NeuroImage Clin. 2019, 22, 101779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egashira, S.; Shin, J.H.; Yoshimura, S.; Koga, M.; Ihara, M.; Kimura, N.; Toda, T.; Imanaka, Y. Cost-effectiveness of endovascular therapy for acute stroke with a large ischemic region in Japan: Impact of the Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score on cost-effectiveness. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 2023, 17, e60–e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.Z.; Lin, H.A.; Bai, C.H.; Lin, S.F. Posterior circulation acute stroke prognosis early CT scores in predicting functional outcomes: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezova, V.; Moen, K.G.; Skandsen, T.; Vik, A.; Brewer, J.B.; Salvesen, Ø.; Håberg, A.K. Prospective longitudinal MRI study of brain volumes and diffusion changes during the first year after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. Neuroimage Clin. 2014, 5, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasmin, A.; Pitkänen, A.; Andrade, P.; Paananen, T.; Gröhn, O.; Immonen, R. Post-injury ventricular enlargement associates with iron in choroid plexus but not with seizure susceptibility nor lesion atrophy-6-month MRI follow-up after experimental traumatic brain injury. Brain Struct. Funct. 2022, 227, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.E.; Park, J.H.; Schellingerhout, D.; Ryu, W.S.; Lee, S.K.; Jang, M.U.; Jeong, S.W.; Na, J.Y.; Park, J.E.; Lee, E.J.; et al. Mapping the Supratentorial Cerebral Arterial Territories Using 1160 Large Artery Infarcts. JAMA Neurol. 2019, 76, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatu, L.; Moulin, T.; Bogousslavsky, J.; Duvernoy, H. Arterial territories of the human brain: Cerebral hemispheres. Neurology 1998, 50, 1699–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosner, J.; Reddy, V.; Lui, F. Neuroanatomy, Circle of Willis; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka, F.; Yasuda, S.; Noguchi, T.; Ishibashi-Ueda, H. Pathology of coronary atherosclerosis and thrombosis. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2016, 6, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-F.; Tang, S.-C.; Wu, W.-C.; Kao, H.-L.; Kuo, Y.-S.; Yang, S.-C. Alterations of cerebral perfusion in asymptomatic internal carotid artery steno-occlusive disease. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, W.; Morgello, S.; Goldman, J.; Mohr, J.P.; Elkind, M.S.; Marshall, R.S.; Gutierrez, J. Histopathological Differences Between the Anterior and Posterior Brain Arteries as a Function of Aging. Stroke 2017, 48, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidoiu, A.-M.; Mincă, D.I.; Rusu, M.C.; Hostiuc, S.; Toader, C. The Fetal Type of Posterior Cerebral Artery. Medicina 2023, 59, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Chen, Q.; Li, Z.-Y. A 3D numerical study of the collateral capacity of the circle of Willis with anatomical variation in the posterior circulation. Biomed. Eng. Online 2015, 14 (Suppl. S1), S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.D.; Li, B. Neural–metabolic coupling in the central visual pathway. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 371, 20150357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.; Park, H.J. A populational connection distribution map for the whole brain white matter reveals ordered cortical wiring in the space of white matter. Neuroimage 2022, 254, 119167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radomski, K.L.; Zi, X.; Lischka, F.W.; Noble, M.D.; Galdzicki, Z.; Armstrong, R.C. Acute axon damage and demyelination are mitigated by 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) therapy after experimental traumatic brain injury. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2022, 10, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trapp, B.D.; Vignos, M.; Dudman, J.; Chang, A.; Fisher, E.; Staugaitis, S.M.; Battapady, H.; Mork, S.; Ontaneda, D.; E Jones, S.; et al. Cortical neuronal densities and cerebral white matter demyelination in multiple sclerosis: A retrospective study. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 870–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coupé, P.; Manjón, J.V.; Lanuza, E.; Catheline, G. Lifespan Changes of the Human Brain in Alzheimer’s Disease. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelman, A.P.; van der Graaf, Y.; Vincken, K.L.; Tiehuis, A.M.; Witkamp, T.D.; Mali, W.P.; I Geerlings, M.; SMART Study Group. Total cerebral blood flow, white matter lesions and brain atrophy: The SMART-MR study. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2008, 28, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, D.E.; Seabaugh, J.D.; Seabaugh, J.M.; Alvarez, C.; Ellis, L.P.; Powell, C.; Reese, C.; Cooper, L.; Shepherd, K. Journey to the other side of the brain: Asymmetry in patients with chronic mild or moderate traumatic brain injury. Concussion 2022, 8, Cnc101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutu, J.P.; Goldblatt, A.; Rosas, H.D.; Salat, D.H. White Matter Changes are Associated with Ventricular Expansion in Aging, Mild Cognitive Impairment, and Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2016, 49, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, A.; Schmalfuss, I.; Heaton, S.C.; Gabrielli, A.; Hannay, H.J.; Papa, L.; Brophy, G.M.; Wang, K.K.; Büki, A.; Schwarcz, A.; et al. Lateral Ventricle Volume Asymmetry Predicts Midline Shift in Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neurotrauma 2015, 32, 1307–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaznawi, R.; Zwartbol, M.H.; Zuithoff, N.P.; de Bresser, J.; Hendrikse, J.; I Geerlings, M.; UCC-SMART Study Group. Reduced parenchymal cerebral blood flow is associated with greater progression of brain atrophy: The SMART-MR study. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2021, 41, 1229–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloppenborg, R.P.; Nederkoorn, P.J.; Grool, A.M.; Vincken, K.L.; Mali, W.P.T.M.; Vermeulen, M.; van der Graff, Y.; I Geerlings, M.; SMART Study Group. Cerebral small-vessel disease and progression of brain atrophy: The SMART-MR study. Neurology 2012, 79, 2029–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabizadeh, F.; Balabandian, M.; Rostami, M.R.; Mehrabi, S.; Sedighi, M. Regional cerebral blood flow and brain atrophy in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurol. Lett. 2023, 2, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Liu, Q.; Wang, X.; Chen, S.; Xu, B.; Zhu, C.; Lu, J. Chronic intracranial artery stenosis: Comparison of whole-brain arterial spin labeling with CT perfusion. Clin. Imaging 2018, 52, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia Maciel, R.; Lee, W.J.; Aguiar De Macedo, B.; Barbosa Pereira Da Silva, D.; Boutrik, A.; Merighi, M.C.; Ferreira Neves, H.A.; Braga Salles Machado, L.; Giancristoforo Campos, B. Cortical venous opacification score predicts outcomes after thrombectomy in large vessel occlusion stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroradiology 2025, 67, 2483–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, W.S.; Dayton, O.; Lucke-Wold, B.; Reitano, C.; Sorrentino, Z.; Busl, K.M. Decrease in cortical vein opacification predicts outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J. NeuroInterv. Surg. 2023, 15, 1105–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Statistics Mean ± SD or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 60.7 ± 9.1 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 34 (36.2) |

| Male | 60 (63.8) |

| Side of larger ventricle volume | |

| Left side | 55 (58.5) |

| Right side | 39 (41.5) |

| Presence of cerebral artery stenosis | |

| No stenosis | 25 (26.6) |

| Unilateral stenosis | 46 (48.9) |

| Bilateral stenosis | 23 (24.5) |

| Follow-up | |

| Death | 12 (12.8) |

| Stroke | 22 (23.4) |

| SLV Side | LLV Side | Paired Difference a,b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD (mL/100 g/min) | Relative CBF, Mean ± SD, % | p-Value | ||

| Lateral ventricle volume, mm3 | 37,109.7 ± 28,289.8 | 48,292.8 ± 34,112.3 | ||

| CBF relative value, % | 72.5 ± 33.4 | 66.7 ± 29.8 | 110.2 ± 26.6 | 0.0004 * |

| ACA | 68.4 ± 33.2 | 62.7 ± 31.1 | 112.3 ± 32.5 | 0.0016 * |

| ROI 1 | 63.1 ± 36.6 | 55.0 ± 32.1 | 124.6 ± 56.1 | 0.0026 * |

| ROI 3 | 66.2 ± 37.5 | 56.7 ± 29.8 | 120.0 ± 40.9 | <0.001 * |

| ROI 6 | 67.0 ± 35.8 | 61.3 ± 31.2 | 113.3 ± 42.3 | 0.0315 |

| ROI 11 | 77.3 ± 42.6 | 77.8 ± 44.2 | 108.3 ± 47.4 | 0.8723 |

| MCA | 76.3 ± 37.4 | 65.7 ± 30.1 | 123.1 ± 57.8 | 0.0004 * |

| ROI 2 | 70.1 ± 37.5 | 59.3 ± 30.0 | 133.8 ± 102.7 | 0.0010 * |

| ROI 4 | 64.9 ± 34.6 | 55.5 ± 28.9 | 131.5 ± 85.3 | 0.0026 * |

| ROI 7 | 94.4 ± 81.9 | 74.5 ± 35.3 | 142.2 ± 126.2 | 0.0142 |

| ROI 8 | 83.8 ± 42.6 | 80.6 ± 43.2 | 110.8 ± 49.2 | 0.3908 |

| ROI 12 | 68.2 ± 38.6 | 58.4 ± 31.9 | 132.3 ± 123.8 | 0.0002 * |

| PCA | 71.9 ± 35.2 | 72.0 ± 34.6 | 100.9 ± 16.1 | 0.9190 |

| ROI 5 | 65.1 ± 33.8 | 63.3 ± 38.3 | 110.1 ± 34.4 | 0.3558 |

| ROI 9 | 82.3 ± 44.3 | 81.5 ± 41.7 | 102.6 ± 24.0 | 0.7420 |

| ROI 10 | 71.1 ± 37.9 | 72.9 ± 37.7 | 102.6 ± 41.5 | 0.4179 |

| ROI 13 | 69.2 ± 36.1 | 70.3 ± 37.1 | 101.5 ± 30.5 | 0.5376 |

| Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient, r | With Unilateral Stenosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 94) | Yes (n = 46) | No (n = 48) | |

| ACA | 0.182 | 0.194 | 0.178 |

| ROI 1 | 0.162 | 0.245 | 0.136 |

| ROI 3 | 0.247 * | 0.266 | 0.331 * |

| ROI 6 | 0.212 * | 0.283 | 0.182 |

| ROI 11 | −0.046 | −0.106 | −0.042 |

| MCA | −0.069 | −0.079 | −0.052 |

| ROI 2 | −0.032 | −0.086 | 0.077 |

| ROI 4 | 0.011 | −0.049 | 0.105 |

| ROI 7 | −0.116 | −0.098 | −0.136 |

| ROI 8 | 0.014 | 0.015 | 0.032 |

| ROI 12 | −0.056 | 0.055 | −0.083 |

| PCA | −0.010 | −0.279 | 0.116 |

| ROI 5 | 0.181 | 0.078 | 0.273 |

| ROI 9 | −0.043 | −0.212 | 0.060 |

| ROI 10 | 0.136 | −0.138 | 0.207 |

| ROI 13 | −0.023 | −0.182 | 0.023 |

| Any Stenosis | Unilateral Stenosis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | p-Value | OR | p-Value | |

| Lateral ventricle volume difference, mm3 | 1.00 (0.999, 1.00) | 0.647 | 1.00 (0.999, 1.000) | 0.209 |

| CBF relative value, % | 1.030 (0.999, 1.061) | 0.055 | 1.004 (0.989, 1.020) | 0.604 |

| ACA | 1.011 (0.994, 1.029) | 0.213 | 0.998 (0.986, 1.011) | 0.773 |

| ROI 1 | 1.003 (0.994, 1.012) | 0.499 | 1.001 (0.994, 1.008) | 0.770 |

| ROI 3 | 1.010 (0.996, 1.024) | 0.149 | 1.007 (0.996, 1.017) | 0.207 |

| ROI 6 | 1.006 (0.992, 1.021) | 0.369 | 0.998 (0.989, 1.008) | 0.750 |

| ROI 11 | 1.003 (0.993, 1.014) | 0.552 | 0.995 (0.986, 1.004) | 0.323 |

| MCA | 1.026 (1.004, 1.048) | 0.019 | 1.004 (0.996, 1.011) | 0.352 |

| ROI 2 | 1.022 (1.002, 1.042) | 0.029 | 1.005 (0.999, 1.011) | 0.126 |

| ROI 4 | 1.014 (1.001, 1.027) | 0.038 | 1.003 (0.998, 1.008) | 0.302 |

| ROI 7 | 1.015 (1.000, 1.029) | 0.046 | 0.999 (0.995, 1.002) | 0.473 |

| ROI 8 | 1.015 (0.996, 1.034) | 0.113 | 1.003 (0.994, 1.011) | 0.547 |

| ROI 12 | 0.999 (0.995, 1.002) | 0.460 | 0.999 (0.996, 1.003) | 0.719 |

| PCA | 1.00 (0.97, 1.03) | 0.922 | 1.004 (0.979, 1.030) | 0.749 |

| ROI 5 | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 0.966 | 1.002 (0.990, 1.014) | 0.726 |

| ROI 9 | 1.00 (0.99, 1.02) | 0.648 | 1.005 (0.988, 1.023) | 0.540 |

| ROI 10 | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 0.906 | 0.998 (0.987, 1.008) | 0.641 |

| ROI 13 | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 0.468 | 0.998 (0.984, 1.011) | 0.736 |

| Crude HR (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) a | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lateral ventricle volume difference, mm3 | 1.00 (0.999, 1.00) | 0.679 | 1.00 (0.999, 1.000) | 0.574 |

| CBF relative value, % | 1.004 (0.990–1.017) | 0.609 | 1.005 (0.991–1.019) | 0.516 |

| ACA | 1.003 (0.991–1.015) | 0.610 | 1.003 (0.991–1.015) | 0.621 |

| ROI 1 | 0.997 (0.989–1.006) | 0.536 | 0.998 (0.989–1.006) | 0.579 |

| ROI 3 | 1.000 (0.989–1.010) | 0.970 | 1.001 (0.990–1.012) | 0.850 |

| ROI 6 | 1.006 (0.997–1.014) | 0.182 | 1.006 (0.998–1.014) | 0.175 |

| ROI 11 | 1.003 (0.995–1.010) | 0.447 | 1.002 (0.995–1.010) | 0.568 |

| MCA | 0.999 (0.992–1.007) | 0.851 | 1.000 (0.992–1.008) | 0.969 |

| ROI 2 | 0.999 (0.994–1.004) | 0.716 | 1.000 (0.995–1.004) | 0.921 |

| ROI 4 | 0.999 (0.993–1.004) | 0.623 | 0.999 (0.993–1.005) | 0.750 |

| ROI 7 | 0.998 (0.993–1.003) | 0.456 | 0.998 (0.993–1.003) | 0.415 |

| ROI 8 | 1.000 (0.992–1.008) | 0.975 | 1.000 (0.992–1.009) | 0.914 |

| ROI 12 | 1.000 (0.998–1.003) | 0.775 | 1.000 (0.998–1.003) | 0.854 |

| PCA | 1.028 (1.008–1.049) | 0.005 | 1.029 (1.010–1.049) | 0.003 |

| ROI 5 | 1.007 (0.996–1.017) | 0.209 | 1.008 (0.997–1.019) | 0.142 |

| ROI 9 | 1.001 (0.984–1.018) | 0.906 | 1.001 (0.985–1.018) | 0.862 |

| ROI 10 | 1.008 (1.001–1.014) | 0.017 | 1.007 (1.001–1.014) | 0.022 |

| ROI 13 | 1.014 (1.005–1.022) | 0.003 | 1.013 (1.004–1.022) | 0.003 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, X.; Gao, W.; Gao, S.; Wang, X.; Feng, H. The Correlation Between Lateral Ventricle Asymmetry and Cerebral Blood Flow: Implications for Stroke Risk. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3126. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243126

Sun X, Gao W, Gao S, Wang X, Feng H. The Correlation Between Lateral Ventricle Asymmetry and Cerebral Blood Flow: Implications for Stroke Risk. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3126. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243126

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Xiaojia, Wenjie Gao, Shanshan Gao, Xudong Wang, and Honglin Feng. 2025. "The Correlation Between Lateral Ventricle Asymmetry and Cerebral Blood Flow: Implications for Stroke Risk" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3126. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243126

APA StyleSun, X., Gao, W., Gao, S., Wang, X., & Feng, H. (2025). The Correlation Between Lateral Ventricle Asymmetry and Cerebral Blood Flow: Implications for Stroke Risk. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3126. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243126