Thrombophilia-Related Single Nucleotide Variants and Altered Coagulation Parameters in a Cohort of Mexican Women with Recurrent Pregnancy Loss

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patients

2.2. Metabolite Analysis: Coagulation and Hemostatic Biomarkers

2.3. Genotyping

2.4. Statistical Methods

3. Results

Genotype-Metabolite Associations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGT | Angiotensinogen gene |

| aPTT | Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| F2 | Coagulation Factor II (Prothrombin) |

| F5 | Coagulation Factor V |

| F7 | Coagulation Factor VII |

| F12 | Coagulation Factor XII |

| F13A1 | Coagulation Factor XIII A1 Subunit |

| FGB | Fibrinogen Beta Chain gene |

| FXII | Coagulation Factor XII protein |

| HWE | Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium |

| INR | International Normalized Ratio |

| MAF | Minor Allele Frequency |

| MTHFR | 5,10-Methylenetetrahydrofolate Reductase gene |

| MTR | 5-Methyltetrahydrofolate–Homocysteine Methyltransferase gene |

| MTRR | Methionine Synthase Reductase gene |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PT | Prothrombin Time |

| RPL | Recurrent Pregnancy Loss |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SERPINE1 | Serpin Family E Member 1 gene (Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1) |

| SNV/SNVs | Single Nucleotide Variant(s) |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| TT | Thrombin Time |

References

- Turesheva, A.; Aimagambetova, G.; Ukybassova, T.; Marat, A.; Kanabekova, P.; Kaldygulova, L.; Amanzholkyzy, A.; Ryzhkova, S.; Nogay, A.; Khamidullina, Z.; et al. Recurrent Pregnancy Loss Etiology, Risk Factors, Diagnosis, and Management. Fresh Look into a Full Box. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; He, H.; Zhao, K. Thrombophilic Gene Polymorphisms and Recurrent Pregnancy Loss: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2023, 40, 1533–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundgaard, E.; Pedersen, M.K.; Bor, P.; Bor, M.V. Revisiting the Link Between Factor XII and Recurrent Pregnancy Loss: A Scoping Review. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2025, 94, e70127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaca, N.; Aktün, L.H. Evaluation of Factor XII Activity in Women with Recurrent Miscarriages. Bezmialem Sci. 2018, 6, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padrnos, L.; Gangaraju, R. Inherited Thrombophilia and Recurrent Miscarriage: Is There a Role for Anticoagulation during Pregnancy? Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2024, 2024, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayal, H.B.; Beksac, M.S. The Effect of Hereditary Thrombophilia on Recurrent Pregnancy Loss: A Retrospective Cohort Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavosh, Z.; Mohammadzadeh, Z.; Alizadeh, S.; Sharifi, M.J.; Hajizadeh, S.; Choobineh, H.; Omidkhoda, A. Factor VII R353Q (Rs6046), FGA A6534G (Rs6050), and FGG C10034T (Rs2066865) Gene Polymorphisms and Risk of Recurrent Pregnancy Loss in Iranian Women. Indian J. Hematol. Blood Transfus. 2024, 40, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Delgado, G.J.; Cantero-Fortiz, Y.; Mendez-Huerta, M.A.; Leon-Gonzalez, M.; Nuñez-Cortes, A.K.; Leon-Peña, A.A.; Olivares-Gazca, J.C.; Ruiz-Argüelles, G.J. Primary Thrombophilia in Mexico XII: Miscarriages Are More Frequent in People with Sticky Platelet Syndrome. Turk. J. Hematol. 2017, 34, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solé, X.; Guinó, E.; Valls, J.; Iniesta, R.; Moreno, V. SNPStats: A Web Tool for the Analysis of Association Studies. Bioinformatics 2006, 22, 1928–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintero-Ramos, A.; Valdez-Velázquez, L.L.; Hernández, G.; Baltazar, L.M.; Padilla-Gutiérrez, J.R.; Valle, Y.; Rodarte, K.; Ortiz, R.; Ortiz-Aranda, M.; Olivares, N. Evaluación de Cinco Polimorfismos de Genes Trombofílicos En Parejas Con Aborto Habitual. Gac. Médica México 2006, 142, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- López-Jiménez, J.J.; Porras-Dorantes, Á.; Juárez-Vázquez, C.I.; García-Ortiz, J.E.; Fuentes-Chávez, C.A.; Lara-Navarro, I.J.; Jaloma-Cruz, A.R. Molecular Thrombophilic Profile in Mexican Patients with Idiopathic Recurrent Pregnancy Loss. Genet. Mol. Res. 2016, 15, 15048728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bordaeva, O.Y.; Derevyanchuk, E.G.; Alset, D.; Amelina, M.A.; Shkurat, T.P. The Prevalence and Linkage Disequilibrium of 21 Genetic Variations Related to Thrombophilia, Folate Cycle, and Hypertension in Reproductive Age Women of Rostov Region (Russia). Ann. Hum. Genet. 2024, 88, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesci, R.S.; Hecking, C.; Racké, B.; Janssen, D.; Dempfle, C.E. Utility of ACMG Classification to Support Interpretation of Molecular Genetic Test Results in Patients with Factor VII Deficiency. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1220813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olgasi, C.; Assanelli, S.; Cucci, A.; Follenzi, A. Hemostasis and Endothelial Functionality: The Double Face of Coagulation Factors. Haematologica 2024, 109, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soria, J.M.; Almasy, L.; Souto, J.C.; Sabater-Lleal, M.; Fontcuberta, J.; Blangero, J. The F7 Gene and Clotting Factor VII Levels: Dissection of a Human Quantitative Trait Locus. Hum. Biol. 2005, 77, 561–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamanaev, A.; Litvak, M.; Gailani, D. Recent Advances in Factor XII Structure and Function. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2022, 29, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnoff, O.D.; Busse, R.J., Jr.; Sheon, R.P. The Demise of John Hageman. N. Engl. J. Med. 1968, 279, 760–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Reyes, V.M.; Hernandez-Juarez, J.; Arreola-Diaz, R.; Majluf-Cruz, K.; Reyes-Maldonado, E.; Alvarado-Moreno, J.A.; Ruiz, L.A.M.; Majluf-Cruz, A. Factor XII Deficiency in Mexico: High Prevalence in the General Population and Patients with Venous Thromboembolic Disease. Arch. Med. Res. 2024, 55, 102913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calafell, F.; Almasy, L.; Sabater-Lleal, M.; Buil, A.; Mordillo, C.; Ramírez-Soriano, A.; Sikora, M.; Souto, J.C.; Blangero, J.; Fontcuberta, J.; et al. Sequence Variation and Genetic Evolution at the Human F12 Locus: Mapping Quantitative Trait Nucleotides That Influence FXII Plasma Levels. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009, 19, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, N.; Maihofer, A.X.; Mir, S.A.; Rao, F.; Zhang, K.; Khandrika, S.; Mahata, M.; Friese, R.S.; Hightower, C.M.; Mahata, S.K.; et al. Polymorphisms at the F12 and KLKB1 Loci Have Significant Trait Association with Activation of the Renin-Angiotensin System. BMC Med. Genet. 2016, 17, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabater-Lleal, M.; Chillón, M.; Mordillo, C.; Martínez, Á.; Gil, E.; Mateo, J.; Blangero, J.; Almasy, L.; Fontcuberta, J.; Soria, J.M. Combined Cis-Regulator Elements as Important Mechanism Affecting FXII Plasma Levels. Thromb. Res. 2010, 125, e55–e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaji, T.; Okamura, T.; Osaki, K.; Kuroiwa, M.; Shimoda, K.; Hamasaki, N.; Niho, Y. A Common Genetic Polymorphism (46 C to T Substitution) in the 5′-Untranslated Region of the Coagulation Factor XII Gene Is Associated with Low Translation Efficiency and Decrease in Plasma Factor XII Level. Blood J. Am. Soc. Hematol. 1998, 91, 2010–2014. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, N.C.; Butenas, S.; Lange, L.A.; Lange, E.M.; Cushman, M.; Jenny, N.S.; Walston, J.; Souto, J.C.; Soria, J.M.; Chauhan, G.; et al. Coagulation Factor XII Genetic Variation, Ex Vivo Thrombin Generation, and Stroke Risk in the Elderly: Results from the Cardiovascular Health Study. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2015, 13, 1867–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.Y.; Tuite, A.; Morange, P.E.; Tregouet, D.A.; Gagnon, F. The Factor XII -4C>T Variant and Risk of Common Thrombotic Disorders: A HuGE Review and Meta-Analysis of Evidence from Observational Studies. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 173, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salloum-Asfar, S.; de la Morena-Barrio, M.E.; Esteban, J.; Miñano, A.; Aroca, C.; Vicente, V.; Roldán, V.; Corral, J. Assessment of Two Contact Activation Reagents for the Diagnosis of Congenital Factor XI Deficiency. Thromb. Res. 2018, 163, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, L.C.; Cushman, M.; Pankow, J.S.; Basu, S.; Boerwinkle, E.; Folsom, A.R.; Tang, W. A Genetic Association Study of Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time in European Americans and African Americans: The ARIC Study. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015, 24, 2401–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohmann, J.L.; de Haan, H.G.; Algra, A.; Vossen, C.Y.; Rosendaal, F.R.; Siegerink, B. Genetic Determinants of Activity and Antigen Levels of Contact System Factors. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2019, 17, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covali, R.; Socolov, D.; Socolov, R. Coagulation Tests and Blood Glucose before Vaginal Delivery in Healthy Teenage Pregnant Women Compared with Healthy Adult Pregnant Women. Medicine 2019, 98, e14360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Metabolite | B9 | B12 | H | F | AIII | TT | TP | TTPA | DD | INR | FXII | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNV | ||||||||||||

| AGT rs4762 | 0.151 | 0.731 | 0.208 | 0.47 | 0.602 | 0.521 | 0.993 | 0.594 | 0.712 | 0.705 | 0.846 | |

| AGT rs699 | 0.044 * | 0.547 | 0.827 | 0.200 | 0.475 | 0.196 | 0.631 | 0.745 | 0.042 * | 0.423 | 0.139 | |

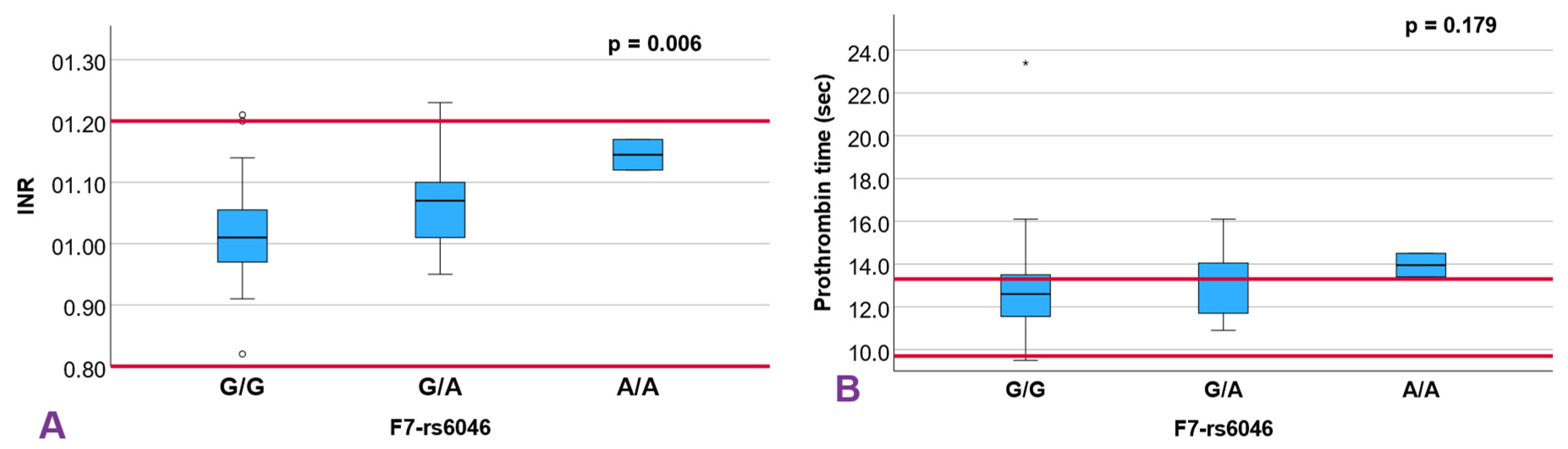

| F7 rs6046 | 0.233 | 0.251 | 0.498 | 0.628 | 0.266 | 0.865 | 0.179 | 0.930 | 0.760 | 0.006 ** | 0.105 | |

| FGB rs1800790 | 0.266 | 0.863 | 0.586 | 0.453 | 0.946 | 0.361 | 0.157 | 0.335 | 0.296 | 0.166 | 0.667 | |

| MTR rs1805087 | 0.783 | 0.351 | 0.107 | 0.111 | 0.840 | 0.453 | 0.550 | 0.871 | 0.956 | 0.641 | 0.907 | |

| MTRR rs1801394 | 0.521 | 0.466 | 0.326 | 0.913 | 0.331 | 0.436 | 0.998 | 0.027 * | 0.271 | 0.946 | 0.929 | |

| MTHFR rs1801133 | 0.076 | 0.337 | 0.390 | 0.023 * | 0.572 | 0.805 | 0.738 | 0.926 | 0.675 | 0.908 | 0.192 | |

| MTHFR rs1801131 | 0.314 | 0.698 | 0.513 | 0.295 | 0.511 | 0.049 * | 0.032 * | 0.410 | 0.410 | 0.066 | 0.392 | |

| F2 1 rs1799963 | 0.344 | 0.031 * | 1.000 | 0.788 | 0.038 * | 0.735 | 0.076 | 0.171 | 0.667 | 0.824 | NC | |

| F5 1 rs6025 | 0.906 | 0.123 | 0.895 | 0.611 | 0.525 | 0.342 | 0.449 | 0.844 | 0.776 | 1.000 | 0.133 | |

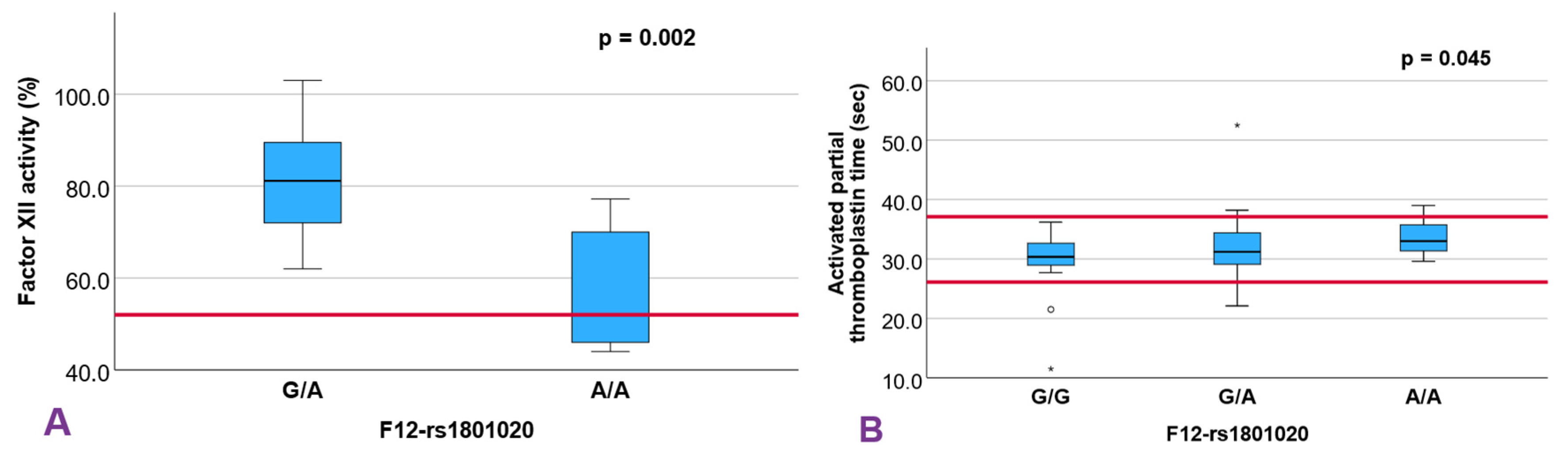

| F12 rs1801020 | 0.651 | 0.638 | 0.404 | 0.204 | 0.315 | 0.223 | 0.506 | 0.045 * | 0.397 | 0.416 | 0.002 ** | |

| F13A1 rs5985 | 0.425 | 0.700 | 0.954 | 0.409 | 0.442 | 0.730 | 0.833 | 0.587 | 0.245 | 0.841 | 0.376 | |

| SERPINE1 rs1799889 | 0.343 | 0.442 | 0.142 | 0.244 | 0.140 | 0.363 | 0.486 | 0.368 | 0.548 | 0.850 | 0.785 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

León-Madero, L.F.; López-Rodriguez, L.; Aguinaga-Ríos, M.; Vargas-Trujillo, S.; Castañeda-de-la-Fuente, A.; Salazar-Villanueva, P.d.C.; Ríos-Lozano, Y.Z.; Martínez-Meza, Y.; Luna-Flores, M.A.; Hidalgo-Bravo, A.; et al. Thrombophilia-Related Single Nucleotide Variants and Altered Coagulation Parameters in a Cohort of Mexican Women with Recurrent Pregnancy Loss. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3111. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243111

León-Madero LF, López-Rodriguez L, Aguinaga-Ríos M, Vargas-Trujillo S, Castañeda-de-la-Fuente A, Salazar-Villanueva PdC, Ríos-Lozano YZ, Martínez-Meza Y, Luna-Flores MA, Hidalgo-Bravo A, et al. Thrombophilia-Related Single Nucleotide Variants and Altered Coagulation Parameters in a Cohort of Mexican Women with Recurrent Pregnancy Loss. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3111. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243111

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeón-Madero, Luis Felipe, Larissa López-Rodriguez, Mónica Aguinaga-Ríos, Samuel Vargas-Trujillo, Angélica Castañeda-de-la-Fuente, Paloma del Carmen Salazar-Villanueva, Yanen Zaneli Ríos-Lozano, Yuridia Martínez-Meza, Monserrat Aglae Luna-Flores, Alberto Hidalgo-Bravo, and et al. 2025. "Thrombophilia-Related Single Nucleotide Variants and Altered Coagulation Parameters in a Cohort of Mexican Women with Recurrent Pregnancy Loss" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3111. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243111

APA StyleLeón-Madero, L. F., López-Rodriguez, L., Aguinaga-Ríos, M., Vargas-Trujillo, S., Castañeda-de-la-Fuente, A., Salazar-Villanueva, P. d. C., Ríos-Lozano, Y. Z., Martínez-Meza, Y., Luna-Flores, M. A., Hidalgo-Bravo, A., Borboa-Olivares, H. J., Zaga-Clavellina, V., & Sevilla-Montoya, R. (2025). Thrombophilia-Related Single Nucleotide Variants and Altered Coagulation Parameters in a Cohort of Mexican Women with Recurrent Pregnancy Loss. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3111. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243111