Evaluation of Model Performance and Clinical Usefulness in Automated Rectal Segmentation in CT for Prostate and Cervical Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Background

3. Materials and Methods

- -

- A sex classification network that predicts the biological sex of each patient from CT images.

- -

- A sex-informed rectum segmentation network using the predicted sex label to guide the segmentation in a sex-specific way. This pipeline takes advantage of sex-specific anatomical priors to enhance the accuracy and generalization without making any alteration to the basic structure of the U-Net.

3.1. Patient Cohort and Data Acquisition

3.2. Data Preprocessing and Ground Truth Mask Definition

3.3. Model Design and Training

3.4. Performance Evaluation Metrics and Statistical Analysis

3.4.1. The Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC)

3.4.2. Average Symmetric Surface Distance (ASD)

3.4.3. The Hausdorff Distance (HD)

3.4.4. Clinical Validation

3.4.5. Sex Prediction Task

3.5. Ethical Considerations and AI Use Declaration

4. Results

4.1. Model Performance in Biological Sex Prediction

4.2. Automated Rectum Segmentation Performance

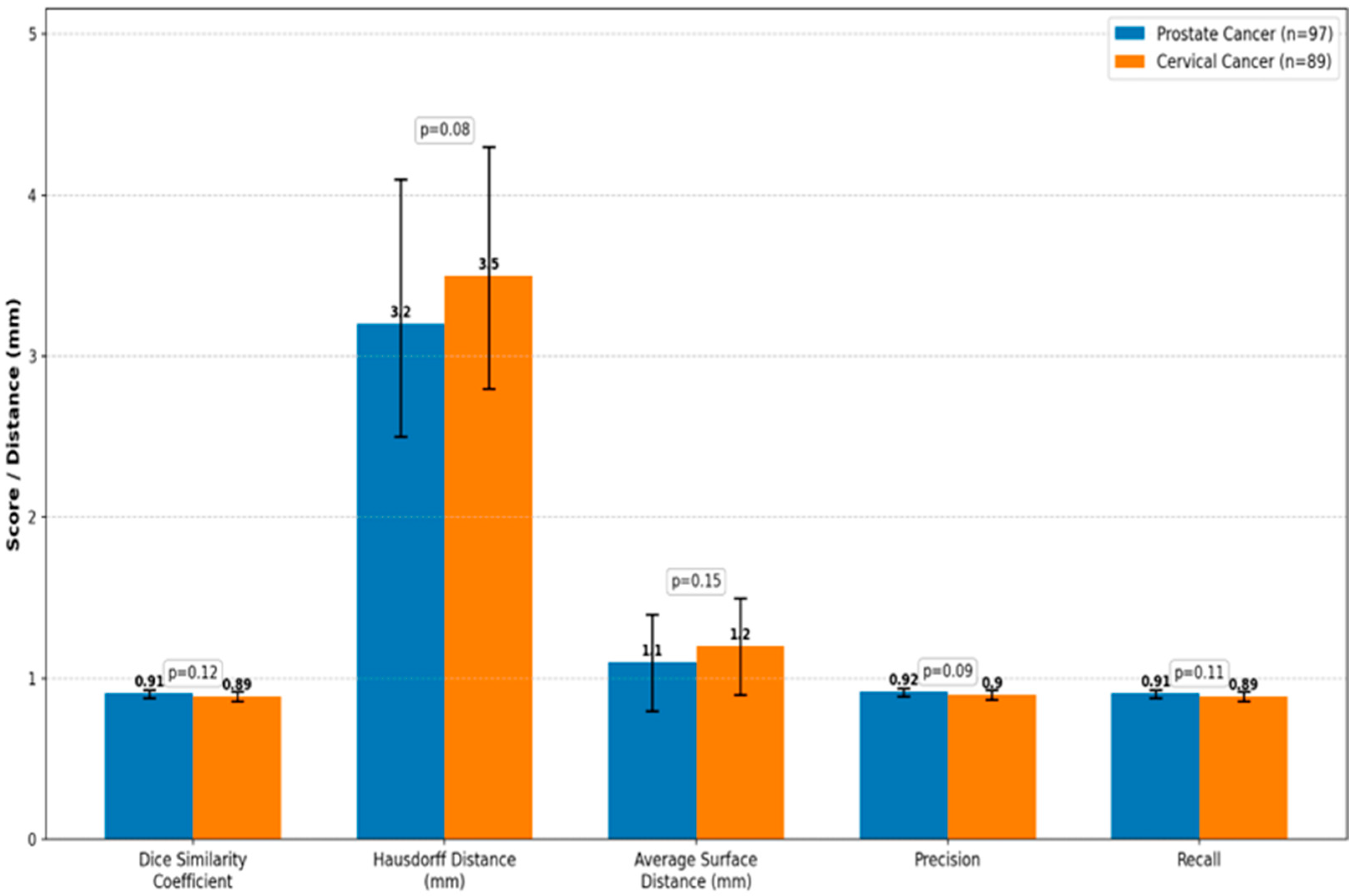

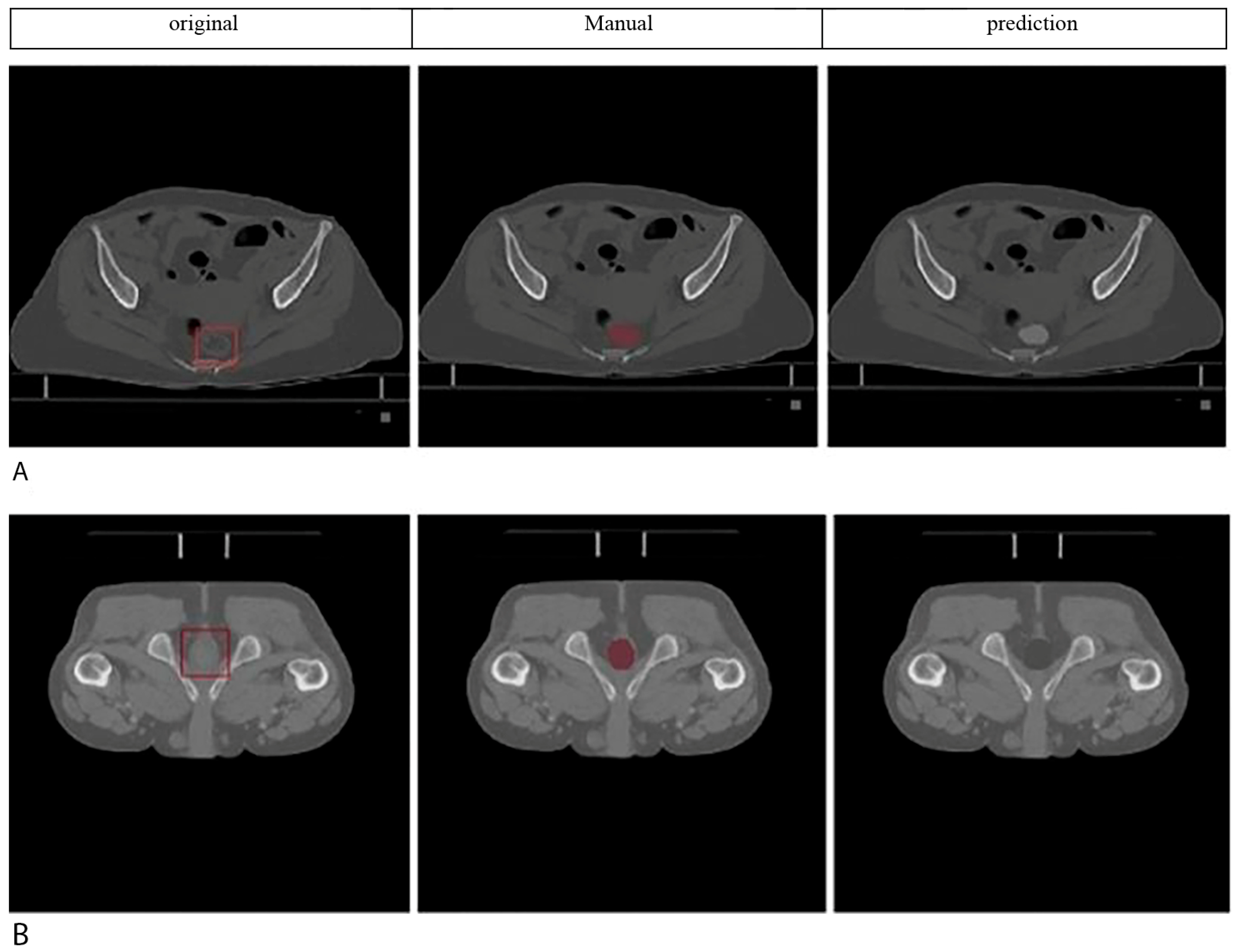

4.3. Comparative Analysis with Expert Manual Segmentation

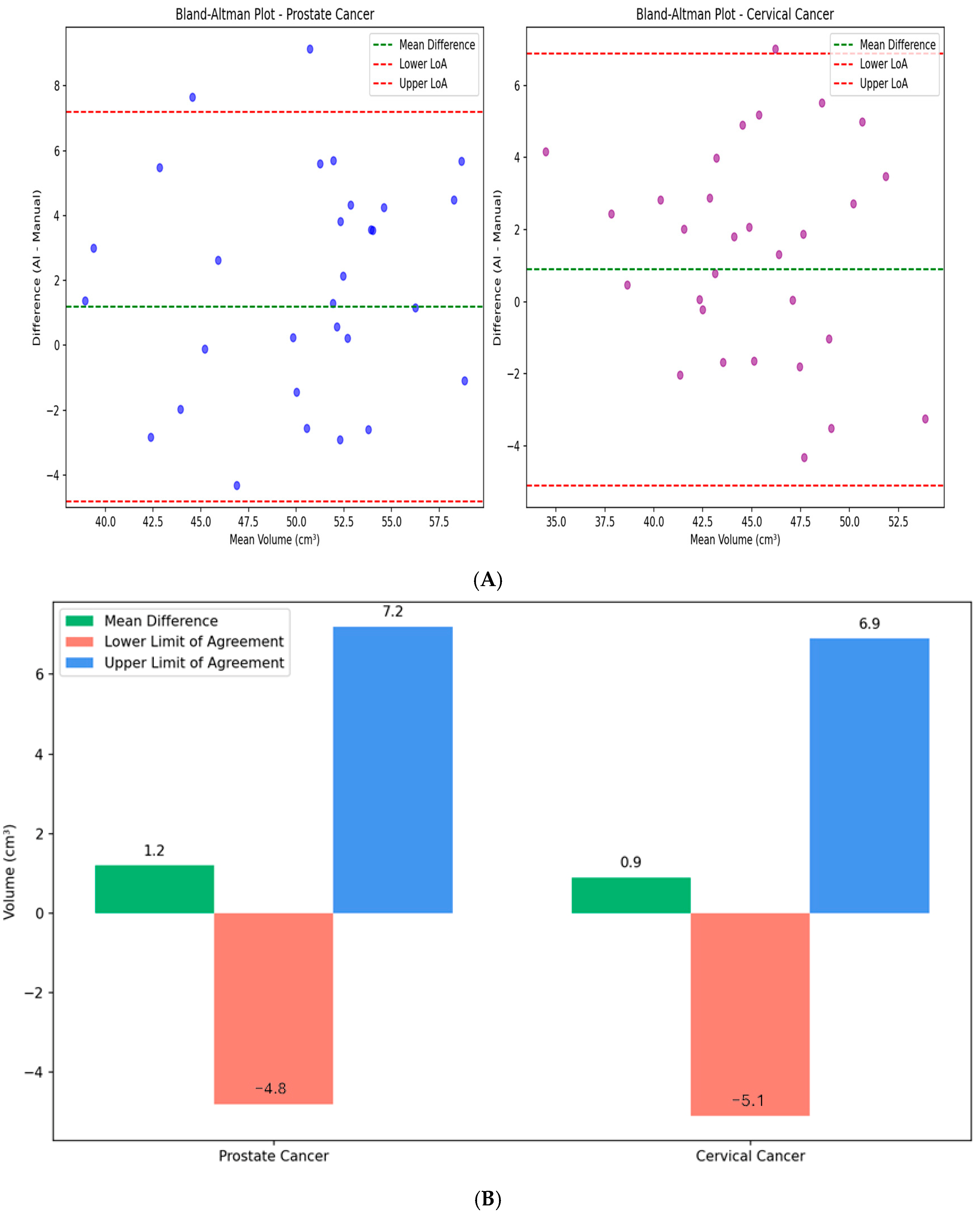

4.4. Retrospective Clinical Validation Results

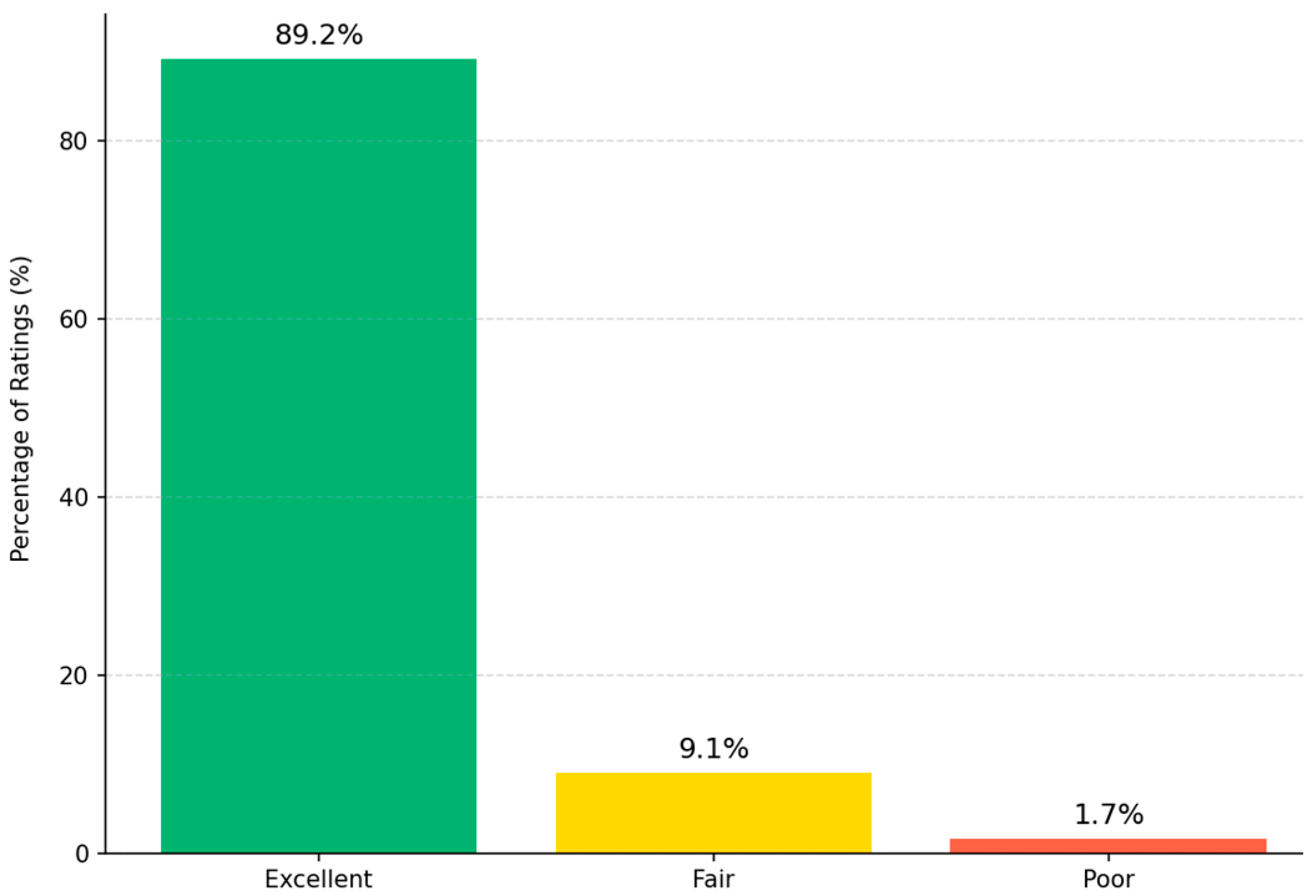

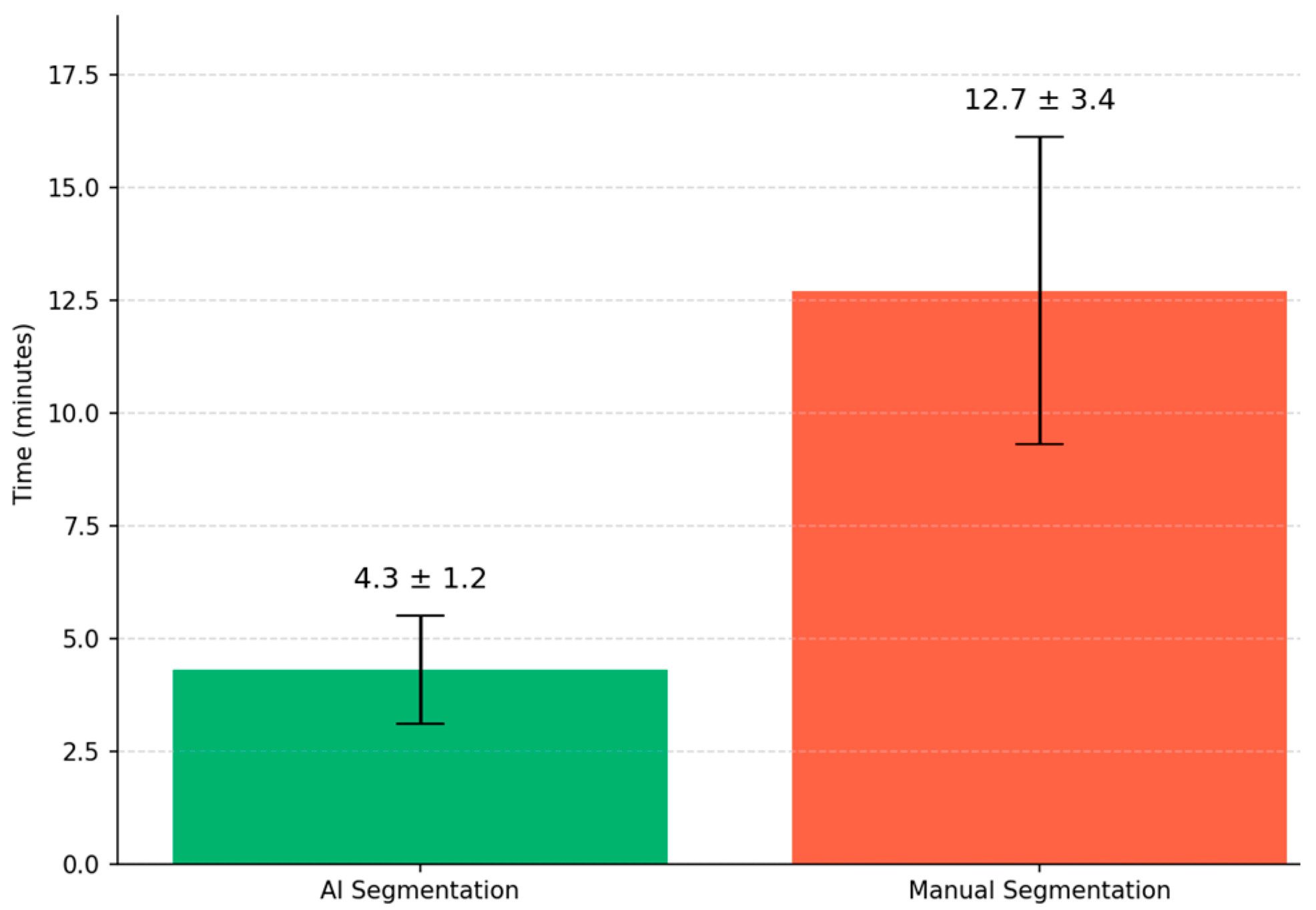

4.5. Processing Time and Computational Efficiency

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baskar, R.; Lee, K.A.; Yeo, R.; Yeoh, K.-W. Cancer and radiation therapy: Current advances and future directions. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2012, 9, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, E.H.; Pollack, A.; Levy, L.; Starkschall, G.; Dong, L.; Rosen, I.; Kuban, D.A. Late rectal toxicity: Dose-volume effects of conformal radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2002, 54, 1314–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalski, J.M.; Gay, H.; Jackson, A.; Tucker, S.L.; Deasy, J.O. Radiation dose–volume effects in radiation-induced rectal injury. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2010, 76, S123–S129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinod, S.K.; Jameson, M.G.; Min, M.; Holloway, L.C. Uncertainties in volume delineation in radiation oncology: A systematic review and recommendations for future studies. Radiother. Oncol. 2016, 121, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litjens, G.; Kooi, T.; Bejnordi, B.E.; Setio, A.A.A.; Ciompi, F.; Ghafoorian, M.; Van Der Laak, J.A.; Van Ginneken, B.; Sánchez, C.I. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 2017, 42, 60–88. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. (Eds.) U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Balagopal, A.; Kazemifar, S.; Nguyen, D.; Lin, M.-H.; Hannan, R.; Owrangi, A.; Jiang, S. Fully automated organ segmentation in male pelvic CT images. Phys. Med. Biol. 2018, 63, 245015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lempart, M.; Nilsson, M.P.; Scherman, J.; Gustafsson, C.J.; Nilsson, M.; Alkner, S.; Engleson, J.; Adrian, G.; Munck af Rosenschöld, P.; Olsson, L.E. Pelvic U-Net: Multi-label semantic segmentation of pelvic organs at risk for radiation therapy anal cancer patients using a deeply supervised shuffle attention convolutional neural network. Radiat. Oncol. 2022, 17, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaedi, E.; Asadi, A.; Hosseini, S.A.; Arabi, H. Enhanced Pelvic CT Segmentation via Deep Learning: A Study on Loss Function Effects. J. Imaging Inform. Med. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.; Cheon, W.; Kim, S.; Park, W.; Han, Y. Deep-learning-based segmentation using individual patient data on prostate cancer radiation therapy. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0308181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantar, R.; Lin, G.; Winfield, J.M.; Messiou, C.; Lalondrelle, S.; Blackledge, M.D.; Koh, D.-M. Automatic segmentation of pelvic cancers using deep learning: State-of-the-art approaches and challenges. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, X.; Zhou, X.; Li, Y.; Huang, Q.; Ni, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, F.; Wen, X.; Cheng, J.; Yuan, Y. Gender-specific data-driven adiposity subtypes using deep-learning-based abdominal CT segmentation. Obesity 2023, 31, 1600–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čevora, K.; Glocker, B.; Bai, W. (Eds.) Quantifying the Impact of Population Shift Across Age and Sex for Abdominal Organ Segmentation. In Proceedings of the MICCAI Workshop on Fairness of AI in Medical Imaging, Marrakesh, Morocco, 6–10 October 2024; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Oktay, O.; Schlemper, J.; Folgoc, L.L.; Lee, M.; Heinrich, M.; Misawa, K.; Mori, K.; McDonagh, S.; Hammerla, N.Y.; Kainz, B. Attention u-net: Learning where to look for the pancreas. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.03999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çiçek, Ö.; Abdulkadir, A.; Lienkamp, S.S.; Brox, T.; Ronneberger, O. (Eds.) 3D U-Net: Learning dense volumetric segmentation from sparse annotation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Athens, Greece, 17–21 October 2016; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas, C.E.; Yang, J.; Anderson, B.M.; Court, L.E.; Brock, K.B. (Eds.) Advances in auto-segmentation. In Seminars in Radiation Oncology; WB Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2019; Volume 29, pp. 185–197. [Google Scholar]

- Lustberg, T.; van Soest, J.; Gooding, M.; Peressutti, D.; Aljabar, P.; van der Stoep, J.; van Elmpt, W.; Dekker, A. Clinical evaluation of atlas and deep learning based automatic contouring for lung cancer. Radiother. Oncol. 2018, 126, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Zhang, L.; Jindal, B.; Alaa, A.; Weinreb, R.; Wilson, D.; Segal, E.; Zou, J. Generative AI Enables Medical Image Segmentation in Ultra Low-Data Regimes. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.17421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belue, M.J.; Harmon, S.A.; Patel, K.; Daryanani, A.; Yilmaz, E.C.; Pinto, P.A.; Wood, B.J.; Citrin, D.E.; Choyke, P.L.; Turkbey, B. Development of a 3D CNN-based AI model for automated segmentation of the prostatic urethra. Acad. Radiol. 2022, 29, 1404–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czipczer, V.; Kolozsvári, B.; Deák-Karancsi, B.; Capala, M.E.; Pearson, R.A.; Borzási, E.; Együd, Z.; Gaál, S.; Kelemen, G.; Kószó, R. Comprehensive deep learning-based framework for automatic organs-at-risk segmentation in head-and-neck and pelvis for MR-guided radiation therapy planning. Front. Phys. 2023, 11, 1236792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Isa, N.A.M.; Chen, C.; Lv, F. Colorectal Polyp Segmentation Based on Deep Learning Methods: A Systematic Review. J. Imaging 2025, 11, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, X.; Guan, H.; Zhen, H.; Sun, Y.; Chen, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wang, S.; Qiu, J. Development and validation of a deep learning algorithm for auto-delineation of clinical target volume and organs at risk in cervical cancer radiotherapy. Radiother. Oncol. 2020, 153, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, A.A.; Hanbury, A. Metrics for evaluating 3D medical image segmentation: Analysis, selection, and tool. BMC Med. Imaging 2015, 15, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimann, T.; Van Ginneken, B.; Styner, M.A.; Arzhaeva, Y.; Aurich, V.; Bauer, C.; Beck, A.; Becker, C.; Beichel, R.; Bekes, G. Comparison and evaluation of methods for liver segmentation from CT datasets. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2009, 28, 1251–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huttenlocher, D.P.; Klanderman, G.A.; Rucklidge, W.J. Comparing images using the Hausdorff distance. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2002, 15, 850–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.-C.; Roth, H.R.; Gao, M.; Lu, L.; Xu, Z.; Nogues, I.; Yao, J.; Mollura, D.; Summers, R.M. Deep convolutional neural networks for computer-aided detection: CNN architectures, dataset characteristics and transfer learning. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2016, 35, 1285–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohavi, R. (Ed.) A study of cross-validation and bootstrap for accuracy estimation and model selection. In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–25 August 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gichoya, J.W.; Banerjee, I.; Bhimireddy, A.R.; Burns, J.L.; Celi, L.A.; Chen, L.-C.; Correa, R.; Dullerud, N.; Ghassemi, M.; Huang, S.-C. AI recognition of patient race in medical imaging: A modelling study. Lancet Digit. Health 2022, 4, e406–e414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSilvio, T.; Antunes, J.T.; Bera, K.; Chirra, P.; Le, H.; Liska, D.; Stein, S.L.; Marderstein, E.; Hall, W.; Paspulati, R. Region-specific deep learning models for accurate segmentation of rectal structures on post-chemoradiation T2w MRI: A multi-institutional, multi-reader study. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1149056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, R.F.; Valdes, G.; Fuller, C.D.; Carpenter, C.M.; Morin, O.; Aneja, S.; Lindsay, W.D.; Aerts, H.J.; Agrimson, B.; Deville, C., Jr. Artificial intelligence in radiation oncology: A specialty-wide disruptive transformation? Radiother. Oncol. 2018, 129, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Model Architecture | Data | Evaluation Metric | Key Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [6] | U-Net (Base Architecture) | Biomedical Images (limited data) | - | Introduced the foundational U-Net architecture, becoming a baseline for many subsequent models. |

| [7] | 3D U-Net | Male Pelvic CT Images | DSC | DSC: 0.94 (mean) for various organs |

| [8] | Pelvic U-Net (Deeply supervised shuffle attention CNN) | Pelvic CT of Anal Cancer Patients and OARs | DSC & Time Savings | DSC: 0.87–0.97 Time: ~40 min (manual) → ~12 min (with correction) → ~4 min (fully automatic) |

| [9] | SegResNet (VAE) | Pelvic CT for OARs | DSC | DSC: 0.86 (achieved with optimized loss function) |

| [10] | Deep Learning-based (Patient-specific nnU-Net) | Prostate CT for Radiation Therapy | DSC | 0.83 ± 0.04 |

| [11] | Review (Various State-of-the-Art Models) | Pelvic Cancers (CT/MRI) | - | Review Article: Discusses current state-of-the-art approaches and challenges in the field. |

| [22] | Deep Learning-based Segmentation Model | Cervical CT for Radiation Therapy | DSC | between 0.82 and 0.87 |

| [12] | Deep Learning-based Segmentation Model | Abdominal CT for Adiposity | - | Identified gender-specific adiposity subtypes from the segmentation data. |

| [19] | CNN-based architecture | prostate and rectal segmentation on CT images | DSC | DSC of over 0.69 |

| [21] | tested 44 segmentation models | - | DSC | DSC: between 0.82 and 0.87 transformer-based models scoring higher than 0.88 |

| Characteristic | Prostate Cancer (n = 97) | Cervical Cancer (n = 89) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 68.0 ± 6.0 | 52.0 ± 6.5 |

| Male, n (%) | 97 (100) | - |

| Female, n (%) | - | 89 (100) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.8 ± 2.5 | 25.4 ± 2.5 |

| CT Slice Thickness (mm) | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Rectal Volume (cm3) | 98.4 ± 14.3 | 86.3 ± 13.2 |

| Metric | Value (%) | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Accuracy | 94.6 | 90.2–97.1 |

| Sensitivity (Male) | 93.5 | 87.9–96.6 |

| Specificity (Female) | 95.7 | 90.8–98.1 |

| Positive Predictive Value | 95.3 | 90.4–97.8 |

| Negative Predictive Value | 94.0 | 89.3–96.8 |

| F1-Score | 94.4 | 90.6–96.7 |

| Metric | Prostate Cancer (n = 97) | Cervical Cancer (n = 89) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) | 0.91 (0.88–0.93) | 0.89 (0.86–0.92) | 0.12 |

| Hausdorff Distance (HD, mm) | 3.2 (2.5–4.1) | 3.5 (2.8–4.3) | 0.08 |

| Average Surface Distance (ASD, mm) | 1.1 (0.8–1.4) | 1.2 (0.9–1.5) | 0.15 |

| Precision | 0.92 (0.89–0.94) | 0.90 (0.87–0.93) | 0.09 |

| Recall | 0.91 (0.88–0.93) | 0.89 (0.86–0.92) | 0.11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Naseri, P.; Shahbazi-Gahrouei, D.; Rajaei-Nejad, S. Evaluation of Model Performance and Clinical Usefulness in Automated Rectal Segmentation in CT for Prostate and Cervical Cancer. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3090. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233090

Naseri P, Shahbazi-Gahrouei D, Rajaei-Nejad S. Evaluation of Model Performance and Clinical Usefulness in Automated Rectal Segmentation in CT for Prostate and Cervical Cancer. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(23):3090. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233090

Chicago/Turabian StyleNaseri, Paria, Daryoush Shahbazi-Gahrouei, and Saeed Rajaei-Nejad. 2025. "Evaluation of Model Performance and Clinical Usefulness in Automated Rectal Segmentation in CT for Prostate and Cervical Cancer" Diagnostics 15, no. 23: 3090. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233090

APA StyleNaseri, P., Shahbazi-Gahrouei, D., & Rajaei-Nejad, S. (2025). Evaluation of Model Performance and Clinical Usefulness in Automated Rectal Segmentation in CT for Prostate and Cervical Cancer. Diagnostics, 15(23), 3090. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233090