Omics Sciences in Dentistry: A Narrative Review on Diagnostic and Therapeutic Applications for Prevalent Oral Diseases

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Genomics in Oral Health and Disease

2.1. Genomics of OSCC

2.2. Genomics of Dental Caries

2.3. Genomics of Periodontal Disease

2.4. Summary and Future Directions

3. Transcriptomics and Gene Expression Profiling

3.1. Transcriptomics of Autoimmune Oral Diseases

3.2. Transcriptomics in Oral Cancer Microenvironment

3.3. Summary and Future Directions

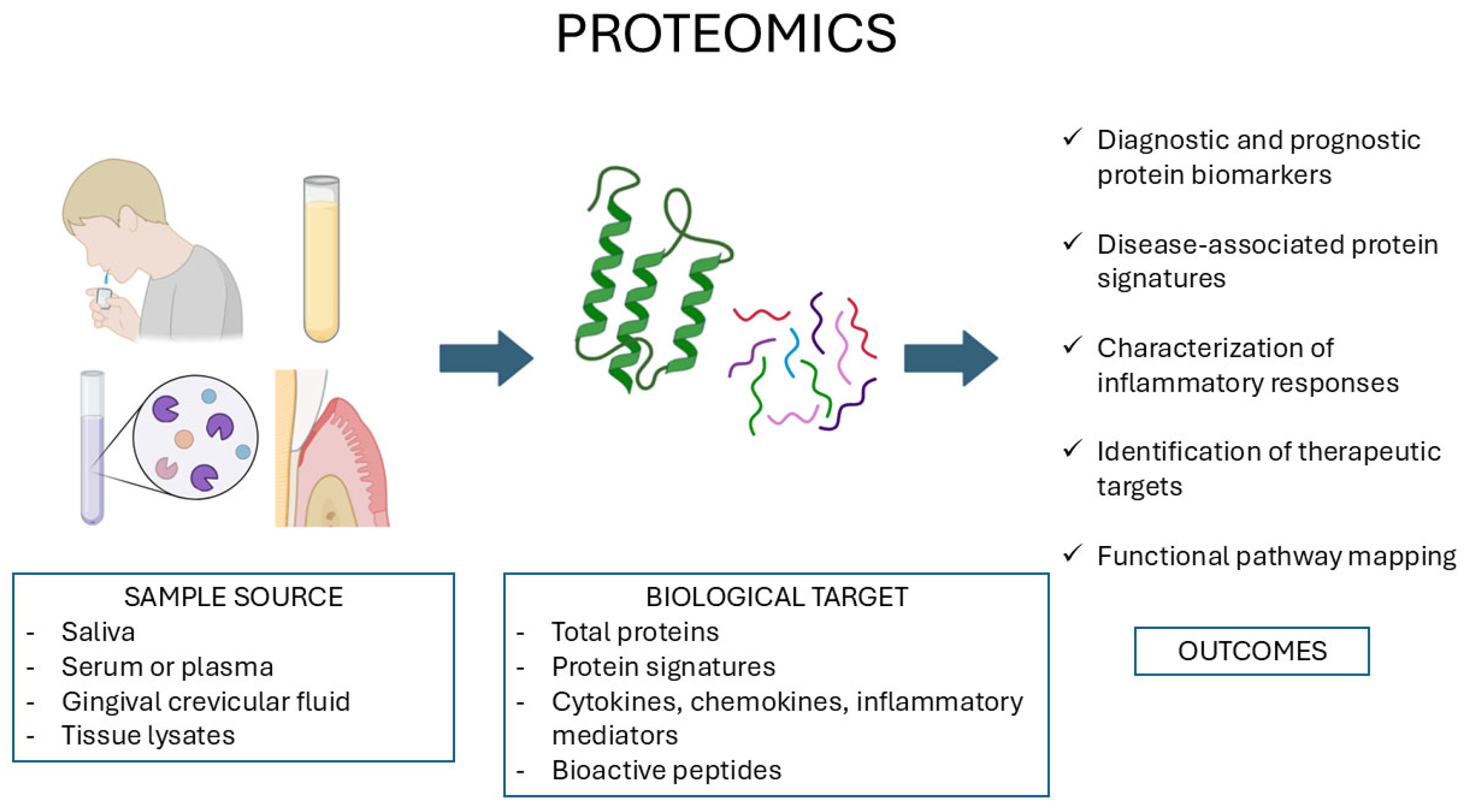

4. Proteomics in Salivary Diagnostics and Tissue Analysis

4.1. Proteomics of Oral Cancer

4.2. Proteomics in Periodontal Disease

4.3. Summary and Future Directions

5. Metabolomics: Metabolic Fingerprinting of Oral Disease

5.1. Metabolomics of OSCC

5.2. Metabolomics in Periodontal Disease

5.3. Summary and Future Directions

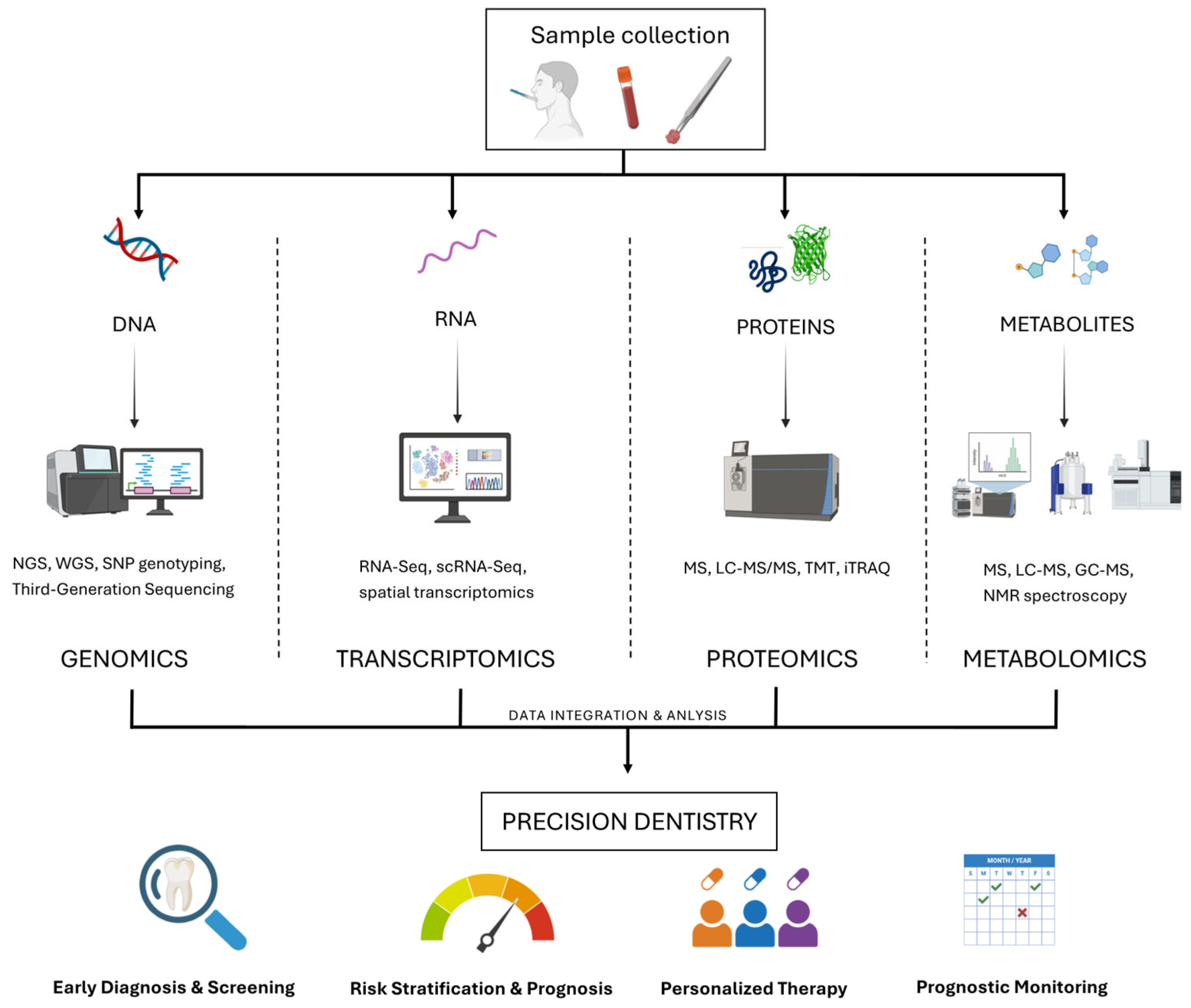

6. Multi-Omics Approaches in Dentistry: From Integration to Precision

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2D-GE | Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis |

| CAFs | Cancer-associated fibroblasts |

| CE-MS | Capillary electrophoresis–mass spectrometry |

| DIA | Data-independent acquisition |

| DMFS | Decayed, missing, and filled surfaces |

| EMT | Epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

| EVs | Extracellular vesicles |

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| GCF | Gingival crevicular fluid |

| GWAS | Genome-wide association study(s) |

| iTRAQ | Isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry |

| LFQ | Label-free quantification |

| lncRNA | Long non-coding RNA |

| MDSCs | Myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| MMPg | Mucous membrane pemphigoid |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| MS | Mass spectrometry |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| OSCC | Oral squamous cell carcinoma |

| p-EMT | Partial epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PLS-DA | Partial least squares discriminant analysis |

| PRS | Polygenic risk score |

| PV | Pemphigus vulgaris |

| RNA-seq | RNA sequencing |

| SCFAs | Short-chain fatty acids |

| scRNA-seq | Single-cell RNA sequencing |

| SS | Sjögren’s syndrome |

| SWATH-MS | Sequential window acquisition of all theoretical mass spectra |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic acid cycle |

| TILs | Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| TMT | Tandem mass tags |

| UPLC-MS | Ultra-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| WES | Whole-exome sequencing |

References

- Giacco, L.D.; Cattaneo, C. Introduction to genomics. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012, 823, 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Green, E.D.; Watson, J.D.; Collins, F.S. Human Genome Project: Twenty-five years of big biology. Nature 2015, 526, 29–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, R.N.; Howe, B.J.; Chernus, J.M.; Mukhopadhyay, N.; Sanchez, C.; Deleyiannis, F.W.B.; Neiswanger, K.; Padilla, C.; Poletta, F.A.; Orioli, I.M.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) of dental caries in diverse populations. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Zhu, H.; Mou, Q.; Wong, P.Y.; Lan, L.; Ng, C.W.K.; Lei, P.; Cheung, M.K.; Wang, D.; Wong, E.W.Y.; et al. Integrative analysis reveals associations between oral microbiota dysbiosis and host genetic and epigenetic aberrations in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2024, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Ahn, K.M. Prognostic factors of oral squamous cell carcinoma: The importance of recurrence and pTNM stage. Maxillofac. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2024, 46, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagaki, T.; Tamura, M.; Kobashi, K.; Koyama, R.; Fukushima, H.; Ohashi, T.; Idogawa, M.; Ogi, K.; Hiratsuka, H.; Tokino, T.; et al. Profiling cancer-related gene mutations in oral squamous cell carcinoma from Japanese patients by targeted amplicon sequencing. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 59113–59122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adorno-Farias, D.; Morales-Pisón, S.; Gischkow-Rucatti, G.; Margarit, S.; Fernández-Ramires, R. Genetic and epigenetic landscape of early-onset oral squamous cell carcinoma: Insights of genomic underserved and underrepresented populations. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2024, 47, e20240036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadeeshan, S.; Novoplansky, O.Z.; Cohen, O.; Kurth, I.; Hess, J.; Rosenberg, A.J.; Grandis, J.R.; Elkabets, M. New insights into RAS in head and neck cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Rev. Cancer 2023, 1878, 188963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, L.G.d.S.; Martins, I.M.; Paulo, E.P.d.A.; Pomini, K.T.; Poyet, J.-L.; Maria, D.A. Molecular Mechanisms in the Carcinogenesis of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Literature Review. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Li, B. STAT3 and Its Targeting Inhibitors in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cells 2022, 11, 3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; An, N.; Wang, M.; Liu, X.; Mei, Z. Downregulation of AT-rich interaction domain 2 underlies natural killer cell dysfunction in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Immunol Cell Biol. 2023, 101, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Zarif, T.; Machaalani, M.; Nawfal, R.; Nassar, A.H.; Xie, W.; Choueiri, T.K.; Pomerantz, M. TERT Promoter Mutations Frequency Across Race, Sex, and Cancer Type. Oncologist 2024, 29, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galati, L.; Chiocca, S.; Duca, D.; Tagliabue, M.; Simoens, C.; Gheit, T.; Arbyn, M.; Tommasino, M. HPV and head and neck cancers: Towards early diagnosis and prevention. Tumour Virus Res. 2022, 14, 200245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitrago-Pérez, Á.; Garaulet, G.; Vázquez-Carballo, A.; Paramio, J.M.; García-Escudero, R. Molecular Signature of HPV-Induced Carcinogenesis: pRb, p53 and Gene Expression Profiling. Curr. Genomics 2009, 10, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.H.; Zhang, Q.; Kong, C.S.; Harris, J.; Fertig, E.J.; Harari, P.M.; Wang, D.; Redmond, K.P.; Shenouda, G.; Trotti, A.; et al. p16 protein expression and human papillomavirus status as prognostic biomarkers of nonoropharyngeal head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 3930–3938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Mai, Z.; Gu, W.; Ogbuehi, A.C.; Acharya, A.; Pelekos, G.; Ning, W.; Liu, X.; Deng, Y.; Li, H.; et al. Molecular Subtypes of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Based on Immunosuppression Genes Using a Deep Learning Approach. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 687245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, Y.; Goldenberg-Cohen, N.; Shalmon, B.; Shani, T.; Oren, S.; Amariglio, N.; Dratviman-Storobinsky, O.; Shnaiderman-Shapiro, A.; Yahalom, R.; Kaplan, I.; et al. Mutational analysis of PTEN/PIK3CA/AKT pathway in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2011, 47, 946–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.; Alam, M.; Kashyap, T.; Nath, N.; Kumari, A.; Pramanik, K.K.; Nagini, S.; Mishra, R. Crosstalk between PD-L1 and Jak2-Stat3/MAPK-AP1 signaling promotes oral cancer progression, invasion and therapy resistance. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 124, 110894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, Y.; Honda, K. Liquid Biopsy for Oral Cancer Diagnosis: Recent Advances and Challenges. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.C.; Jung, S.H.; Shivakumar, M.; Cha, S.; Park, W.Y.; Won, H.H.; Eun, Y.G.; Biobank, P.M.; Kim, D. Polygenic risk score-based phenome-wide association study of head and neck cancer across two large biobanks. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benard, E.L.; Hammerschmidt, M. The fundamentals of WNT10A. Differentiation 2025, 142, 100838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Zhao, R.; He, H.; Zhang, J.; Feng, H.; Lin, L. WNT10A variants are associated with non-syndromic tooth agenesis in the general population. Hum. Genet. 2014, 133, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robino, A.; Bevilacqua, L.; Pirastu, N.; Situlin, R.; Di Lenarda, R.; Gasparini, P.; Navarra, C.O. Polymorphisms in sweet taste genes (TAS1R2 and GLUT2), sweet liking, and dental caries prevalence in an adult Italian population. Genes Nutr. 2015, 10, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Willing, M.C.; Marazita, M.L.; Wendell, S.; Warren, J.J.; Broffitt, B.; Smith, B.; Busch, T.; Lidral, A.C.; Levy, S.M. Genetic and environmental factors associated with dental caries in children: The Iowa Fluoride Study. Caries Res. 2012, 46, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmanov, A.A.; Bosak, N.P.; Lin, C.; Matsumoto, I.; Ohmoto, M.; Reed, D.R.; Nelson, T.M. Genetics of taste receptors. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 2669–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, A.K.; Mennella, J.A. Innate and learned preferences for sweet taste during childhood. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2011, 14, 379–384. [Google Scholar]

- Cecati, M.; Vignini, A.; Borroni, F.; Pugnaloni, S.; Alia, S.; Sabbatinelli, J.; Nicolai, G.; Taus, M.; Santarelli, A.; Fabri, M.; et al. TAS1R3 and TAS2R38 Polymorphisms Affect Sweet Taste Perception: An Observational Study on Healthy and Obese Subjects. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaziri, A.; Dus, M. Brain on food: The neuroepigenetics of nutrition. Neurochem. Int. 2021, 149, 105099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.J.; Mohandas, N.; Craig, J.M.; Manton, D.J.; Saffery, R.; Southey, M.C.; Burgner, D.P.; Lucas, J.; Kilpatrick, N.M.; Hopper, J.L.; et al. DNA methylation in childhood dental caries and hypomineralization. J. Dent. 2022, 117, 103913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, D.; Sun, Y.; Yang, J.; Yu, Y. Association of genetic variants in enamel-formation genes with dental caries: A meta- and gene-cluster analysis. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 1645–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.; Chavez, M.B.; Ikeda, A.; Foster, B.L.; Bartlett, J.D. MMP20 Overexpression Disrupts Molar Ameloblast Polarity and Migration. J. Dent. Res. 2018, 97, 820–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, A.; Espinoza, J.L.; Harkins, D.M.; Leong, P.; Saffery, R.; Bockmann, M.; Torralba, M.; Kuelbs, C.; Kodukula, R.; Inman, J.; et al. Host Genetic Control of the Oral Microbiome in Health and Disease. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 22, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fries, N.; Haworth, S.; Shaffer, J.R.; Esberg, A.; Divaris, K.; Marazita, M.L.; Johansson, I. A Polygenic Score Predicts Caries Experience in Elderly Swedish Adults. J. Dent. Res. 2024, 103, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nibali, L.; Bayliss-Chapman, J.; Almofareh, S.A.; Zhou, Y.; Divaris, K.; Vieira, A.R. What Is the Heritability of Periodontitis? A Systematic Review. J. Dent. Res. 2019, 98, 632–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, R.; Chopra, A.; Dommisch, H.; Schaefer, A.S. Periodontitis Risk Variants at SIGLEC5 Impair ERG and MAFB Binding. J. Dent. Res. 2022, 101, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimbux, N.Y.; Saraiya, V.M.; Elangovan, S.; Allareddy, V.; Kinnunen, T.; Kornman, K.S.; Duff, G.W. Interleukin-1 gene polymorphisms and chronic periodontitis in adult whites: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Periodontol. 2012, 83, 1407–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkinen, A.M.; Kettunen, K.; Kovanen, L.; Haukka, J.; Elg, J.; Husu, H.; Tervahartiala, T.; Pussinen, P.; Meurman, J.; Sorsa, T. Inflammatory mediator polymorphisms associate with initial periodontitis in adolescents. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2016, 2, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, H.; Yan, Y.; Jin, Y.H.; Meng, X.Y.; Mo, Y.Y.; Zeng, X.T. Matrix metalloproteinase gene polymorphisms and periodontitis susceptibility: A meta-analysis involving 6,162 individuals. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Păunică, I.; Giurgiu, M.; Dumitriu, A.S.; Păunică, S.; Pantea Stoian, A.M.; Martu, M.A.; Serafinceanu, C. The Bidirectional Relationship between Periodontal Disease and Diabetes Mellitus-A Review. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, P.; Estrin, N.; Farshidfar, N.; Zhang, Y.; Miron, R.J. Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonists (GLP-1RAs) Improve Periodontal and Peri-Implant Health in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J. Periodontal Res. 2025, 60, 450–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loos, B.G.; Van Dyke, T.E. The role of inflammation and genetics in periodontal disease. Periodontol. 2000 2020, 83, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.D.; Kim, W.J.; Ryoo, H.M.; Kim, H.G.; Kim, K.H.; Ku, Y.; Seol, Y.J. Current advances of epigenetics in periodontology from ENCODE project: A review and future perspectives. Clin. Epigenetics 2021, 13, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tong, X.; Zhu, J.; Tian, L.; Jie, Z.; Zou, Y.; Lin, X.; Liang, H.; Li, W.; Ju, Y.; et al. Metagenome-genome-wide association studies reveal human genetic impact on the oral microbiome. Cell Discov. 2021, 7, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, R.; Shirley, N.; Bleackley, M.; Dolan, S.; Shafee, T. Transcriptomics technologies. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saliminejad, K.; Khorram Khorshid, H.R.; Soleymani Fard, S.; Ghaffari, S.H. An overview of microRNAs: Biology, functions, therapeutics, and analysis methods. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 5451–5465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokes, T.; Cen, H.H.; Kapranov, P.; Gallagher, I.J.; Pitsillides, A.A.; Volmar, C.H.; Kraus, W.E.; Johnson, J.D.; Phillips, S.M.; Wahlestedt, C.; et al. Transcriptomics for Clinical and Experimental Biology Research: Hang on a Seq. Adv. Genet. 2023, 4, 2200024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, W.; Zhu, W.; Dong, J.; Cheng, Y.; Yin, Z.; Shen, F. Mechanisms and Functions of Long Non-Coding RNAs at Multiple Regulatory Levels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gerstein, M.; Snyder, M. RNA-Seq: A revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, V.; Vento-Tormo, R.; Teichmann, S.A. Exponential scaling of single-cell RNA-seq in the past decade. Nat. Protoc. 2018, 13, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundmark, A.; Gerasimcik, N.; Båge, T.; Jemt, A.; Mollbrink, A.; Salmén, F.; Lundeberg, J.; Yucel-Lindberg, T. Gene expression profiling of periodontitis-affected gingival tissue by spatial transcriptomics. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vastrad, S.J.; Saraswathy, G.R.; Dasari, J.B.; Nair, G.; Madarakhandi, A.; Augustine, D.; Sowmya, S.V. A comprehensive transcriptome based meta-analysis to unveil the aggression nexus of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2025, 42, 102001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Zhao, C.; Wei, Q.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, H.; et al. Single cell transcriptome profiling reveals pathogenesis of bullous pemphigoid. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Deng, Y.; Peng, S.; Yan, L.; Xu, H.; Wang, Q.; Shen, Z. RNA-Seq based transcriptome analysis in oral lichen planus. Hereditas 2021, 158, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Kutler, D.; Scognamiglio, T.; Faquin, W.C.; Vered, M.; Reis, P.P.; Nogueira, R.; Santos, M.; Kowalski, L.P.; Katarzyna, P.; et al. Transcriptomic analysis predicts the risk of progression of premalignant lesions in human tongue. Discov. Onc. 2023, 14, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nukaly, H.Y.; Halawani, I.R.; Alghamdi, S.M.S.; Alruwaili, A.G.; Binhezaim, A.; Algahamdi, R.A.A.; Alzahrani, R.A.J.; Alharamlah, F.S.S.; Aldumkh, S.H.S.; Alasqah, H.M.A.; et al. Oral Lichen Planus: A Narrative Review Navigating Etiologies, Clinical Manifestations, Diagnostics, and Therapeutic Approaches. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wu, X.-W.; Zhao, R.-W.; Xu, P.; Zhu, P.-Y.; Tang, K.-L.; He, Y. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Reveals Functional Exhaustion of T Cells in Oral Lichen Planus. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2025, 40, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, F.; Shi, Y.; Zhong, L.; Duan, S.; Kuang, W.; Liu, N.; Luo, E.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, L.; et al. Single-cell immune profiling reveals immune responses in oral lichen planus. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1182732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hébert, V.; Petit, M.; Maho-Vaillant, M.; Golinski, M.L.; Riou, G.; Derambure, C.; Boyer, O.; Joly, P.; Calbo, S. Modifications of the Transcriptomic Profile of Autoreactive B Cells From Pemphigus Patients After Treatment With Rituximab or a Standard Corticosteroid Regimen. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boch, K.; Langan, E.A.; Schmidt, E.; Zillikens, D.; Ludwig, R.J.; Bieber, K.; Hammers, C.M. Sustained CD19+CD27+ Memory B Cell Depletion after Rituximab Treatment in Patients with Pemphigus Vulgaris. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2022, 102, adv00679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.X.; Qu, P.; Wang, K.K.; Zheng, J.; Pan, M.; Zhu, H.Q. Transcriptomic profiling of pemphigus lesion infiltrating mononuclear cells reveals a distinct local immune microenvironment and novel lncRNA regulators. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panthagani, J.; Suleiman, K.; Vincent, R.C.; Ong, H.S.; Wallace, G.R.; Rauz, S. Conjunctival transcriptomics in ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid. Ocul. Surf. 2023, 30, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstappen, G.M.; Gao, L.; Pringle, S.; Haacke, E.A.; van der Vegt, B.; Liefers, S.C.; Patel, V.; Hu, Y.; Mukherjee, S.; Carman, J.; et al. The Transcriptome of Paired Major and Minor Salivary Gland Tissue in Patients With Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 681941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivière, E.; Pascaud, J.; Virone, A.; Dupré, A.; Ly, B.; Paoletti, A.; Seror, R.; Tchitchek, N.; Mingueneau, M.; Smith, N.; et al. Interleukin-7/Interferon Axis Drives T Cell and Salivary Gland Epithelial Cell Interactions in Sjögren’s Syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021, 73, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Dong, X.; Li, B. Tumor microenvironment in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1485174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puram, S.V.; Tirosh, I.; Parikh, A.S.; Patel, A.P.; Yizhak, K.; Gillespie, S.; Rodman, C.; Luo, C.L.; Mroz, E.A.; Emerick, K.S.; et al. Single-Cell Transcriptomic Analysis of Primary and Metastatic Tumor Ecosystems in Head and Neck Cancer. Cell 2017, 171, 1611–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Hong, W.; Wei, X. The molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies of EMT in tumor progression and metastasis. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitoh, M. Involvement of partial EMT in cancer progression. J. Biochem. 2018, 164, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, S.; Waseem, N.H.; Nguyen, T.K.N.; Mohsin, S.; Jamal, A.; Teh, M.T.; Waseem, A. Vimentin Is at the Heart of Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) Mediated Metastasis. Cancers 2021, 13, 4985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arebro, J.; Lee, C.M.; Bennewith, K.L.; Garnis, C. Cancer-Associated Fibroblast Heterogeneity in Malignancy with Focus on Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, S.; Khan, A.A.; Zaheer, S.; Ranga, S. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma and its association with clinicopathological parameters. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2023, 251, 154882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouketsu, A.; Haruka, S.; Kuroda, K.; Hitoshi, M.; Kensuke, Y.; Tsuyoshi, S.; Takahashi, T.; Hiroyuki, K. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cells are associated with oncogenesis of oral squamous cell carcinoma. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2023, 52, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienkowska, K.J.; Hanley, C.J.; Thomas, G.J. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in Oral Cancer: A Current Perspective on Function and Potential for Therapeutic Targeting. Front. Oral Health 2021, 2, 686337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Quazi, S.; Arora, S.; Osellame, L.D.; Burvenich, I.J.; Janes, P.W.; Scott, A.M. Cancer-associated fibroblasts as therapeutic targets for cancer: Advances, challenges, and future prospects. J. Biomed. Sci. 2025, 32, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongpattaraworakul, W.; Choi, A.; Buchakjian, M.R.; Lanzel, E.A.; Kd, A.R.; Simons, A.L. Prognostic Role of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaventura, P.; Shekarian, T.; Alcazer, V.; Valladeau-Guilemond, J.; Valsesia-Wittmann, S.; Amigorena, S.; Caux, C.; Depil, S. Cold Tumors: A Therapeutic Challenge for Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Tan, Y. Promising immunotherapy targets: TIM3, LAG3, and TIGIT joined the party. Mol. Ther. Oncol. 2024, 32, 200773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Li, Y.; Tan, J.; Xu, L.; Li, Y. Targeting LAG-3, TIM-3, and TIGIT for cancer immunotherapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 16, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gstaiger, M.; Aebersold, R. Applying mass spectrometry-based proteomics to genetics, genomics and network biology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.; Schäfer, J.; Kuhn, K.; Kienle, S.; Schwarz, J.; Schmidt, G.; Neumann, T.; Johnstone, R.; Mohammed, A.K.; Hamon, C. Tandem mass tags: A novel quantification strategy for comparative analysis of complex protein mixtures by MS/MS. Anal. Chem. 2003, 75, 1895–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, P.L.; Huang, Y.N.; Marchese, J.N.; Williamson, B.; Parker, K.; Hattan, S.; Khainovski, N.; Pillai, S.; Dey, S.; Daniels, S.; et al. Multiplexed protein quantitation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using amine-reactive isobaric tagging reagents. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2004, 3, 1154–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Yang, Q.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, S.; Tang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xu, H.; Zhu, F. Label-free proteome quantification and evaluation. Brief. Bioinform. 2023, 24, bbac477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Smith, L.S.; Zhu, H.J. Data-independent acquisition (DIA): An emerging proteomics technology for analysis of drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2021, 39, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjo, S.I.; Santa, C.; Manadas, B. SWATH-MS as a tool for biomarker discovery: From basic research to clinical applications. Proteomics 2017, 17, 1600278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, R.T. Single-cell Proteomics: Progress and Prospects. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2020, 19, 1739–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Tao, H.; Xu, T.; Zheng, X.; Wen, C.; Wang, G.; Peng, Y.; Dai, Y. Spatial proteomics: Unveiling the multidimensional landscape of protein localization in human diseases. Proteome Sci. 2024, 22, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler-Barnett, E.H.; Fan, J.; Luo, J.; Magrane, M.; Martin, M.J.; Orchard, S.; UniProt Consortium. UniProt and Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics-A 2-Way Working Relationship. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2023, 22, 100591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, E.W. The PeptideAtlas Project. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010, 604, 285–296. [Google Scholar]

- Thul, P.J.; Lindskog, C. The human protein atlas: A spatial map of the human proteome. Protein Sci. 2018, 27, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granato, D.C.; Carnielli, C.M.; Trino, L.D.; Busso-Lopes, A.F.; Câmara, G.A.; Normando, A.G.C.; Filho, H.V.R.; Domingues, R.R.; Yokoo, S.; Pauletti, B.A.; et al. Mapping Conformational Changes in the Saliva Proteome Potentially Associated with Oral Cancer Aggressiveness. J. Proteome Res. 2024, 23, 2148–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, H.W.; Chang, K.P.; Hsu, C.W.; Chang, I.Y.; Liu, H.P.; Chen, Y.T.; Wu, C.C. Identification of Salivary Biomarkers for Oral Cancer Detection with Untargeted and Targeted Quantitative Proteomics Approaches. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2019, 18, 1796–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cívico-Ortega, J.L.; González-Ruiz, I.; Ramos-García, P.; Cruz-Granados, D.; Samayoa-Descamps, V.; González-Moles, M.Á. Prognostic and Clinicopathological Significance of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) Expression in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Wang, Y.; Gan, M.; Duan, Q. Prognosis and predictive value of heat-shock proteins expression in oral cancer: A PRISMA-compliant meta-analysis. Medicine 2021, 100, e24274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, D.W.; Yang, X.; Yang, C.Z.; Ma, J.; Liu, Y.; Yan, M.; Wang, L.Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, C.P.; Zhang, Z.Y.; et al. Annexin A1 down-regulation in oral squamous cell carcinoma correlates to pathological differentiation grade. Oral Oncol. 2013, 49, 542–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Hou, X.; Feng, H.; Liu, R.; Xu, H.; Gong, W.; Deng, J.; Sun, C.; Gao, Y.; Peng, J.; et al. Proteomic identification of cyclophilin A as a potential biomarker and therapeutic target in oral submucous fibrosis. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 60348–60365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.K.; Sun, Y.; Lv, L.; Ping, Y. ENO1 and Cancer. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics. 2022, 24, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frohwitter, G.; Buerger, H.; van Diest, P.J.; Korsching, E.; Kleinheinz, J.; Fillies, T. Cytokeratin and protein expression patterns in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity provide evidence for two distinct pathogenetic pathways. Oncol. Lett. 2016, 12, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardi, G.; Bellizzi, M.G.; Fatuzzo, I.; Zoccali, F.; Cavalcanti, L.; Greco, A.; Vincentiis, M.; Ralli, M.; Fiore, M.; Petrella, C.; et al. Salivary Biomarkers in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Proteomic Overview. Proteomes 2022, 10, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owecki, W.; Wojtowicz, K.; Nijakowski, K. Salivary Extracellular Vesicles in Detection of Head and Neck Cancers: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2025, 20, 6757–6775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Raimi, H.A.I.; Kong, J.; Ran, Y.; Zhu, L.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Yang, X.; Qi, D.; Liu, T. Extracellular Vesicles from Carcinoma-associated Fibroblasts Promote EMT of Salivary Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma Via IL-6. Arch. Med. Res. 2023, 54, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, S.; Yu, L.; Liu, S.; Li, M.; Jin, F. Extracellular vesicles in oral squamous cell carcinoma: Current progress and future prospect. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1149662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnenberger, H.; Kaderali, L.; Ströbel, P.; Yepes, D.; Plessmann, U.; Dharia, N.V.; Yao, S.; Heydt, C.; Merkelbach-Bruse, S.; Emmert, A.; et al. Comparative proteomics reveals a diagnostic signature for pulmonary head-and-neck cancer metastasis. EMBO Mol. Med. 2018, 10, e8428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, F.; de Sousa, S.C.; Dos Santos, E.; Woo, S.B.; Gallottini, M. PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway proteins are differently expressed in oral carcinogenesis. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2016, 45, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Ma, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Hu, H. NF-κB signaling in inflammation and cancer. MedComm 2021, 2, 618–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, C.; Kamal, F.Z.; Ciobica, A.; Halitchi, G.; Burlui, V.; Petroaie, A.D. Oxidative Stress in the Pathogenesis of Oral Cancer. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aseervatham, J. Cytoskeletal Remodeling in Cancer. Biology 2020, 9, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mischak, H.; Schanstra, J.P.; Vlahou, A.; Beige, J. Clinical Proteomics, Quo Vadis? Proteomics 2025, 25, e202400346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, M.; Kumar, C.; Zeng, W.F.; Strauss, M.T. Artificial intelligence for proteomics and biomarker discovery. Cell Syst. 2021, 12, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, L.G.; Nouh, H.; Salih, E. Quantitative gingival crevicular fluid proteome in health and periodontal disease using stable isotope chemistries and mass spectrometry. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2014, 41, 733–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchida, S.; Satoh, M.; Takiwaki, M.; Nomura, F. Current Status of Proteomic Technologies for Discovering and Identifying Gingival Crevicular Fluid Biomarkers for Periodontal Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, S.P.; Williams, R.; Offenbacher, S.; Morelli, T. Gingival crevicular fluid as a source of biomarkers for periodontitis. Periodontol. 2000 2016, 70, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buduneli, N.; Bıyıkoğlu, B.; Kinane, D.F. Utility of gingival crevicular fluid components for periodontal diagnosis. Periodontol. 2000 2024, 95, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerishnan, J.P.; Mohammad, S.; Alias, M.S.; Mu, A.K.; Vaithilingam, R.D.; Baharuddin, N.A.; Safii, S.H.; Abdul Rahman, Z.A.; Chen, Y.N.; Chen, Y. Identification of biomarkers for periodontal disease using the immunoproteomics approach. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Pintos, T.; Regueira-Iglesias, A.; Relvas, M.; Alonso-Sampedro, M.; Bravo, S.B.; Balsa-Castro, C.; Tomás, I. Diagnostic Accuracy of Novel Protein Biomarkers in Saliva to Detect Periodontitis Using Untargeted ‘SWATH’ Mass Spectrometry. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2025, 52, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellei, E.; Monari, E.; Bertoldi, C.; Bergamini, S. Proteomic Comparison between Periodontal Pocket Tissue and Other Oral Samples in Severe Periodontitis: The Meeting of Prospective Biomarkers. Sci 2024, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silbereisen, A.; Bao, K.; Wolski, W.; Nanni, P.; Kunz, L.; Afacan, B.; Emingil, G.; Bostanci, N. Probing the salivary proteome for prognostic biomarkers in response to non-surgical periodontal therapy. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2025, 52, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.H.; Ivanisevic, J.; Siuzdak, G. Metabolomics: Beyond biomarkers and towards mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyvärinen, E.; Savolainen, M.; Mikkonen, J.J.W.; Kullaa, A.M. Salivary Metabolomics for Diagnosis and Monitoring Diseases: Challenges and Possibilities. Metabolites 2021, 11, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Sun, H.; Wang, P.; Han, Y.; Wang, X. Modern analytical techniques in metabolomics analysis. Analyst 2012, 137, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagana Gowda, G.A.; Raftery, D. NMR-Based Metabolomics. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1280, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.J.; Song, H.E.; Lee, H.Y.; Yoo, H.J. Mass Spectrometry-based Metabolomics in Translational Research. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1310, 509–531. [Google Scholar]

- Höcker, O.; Flottmann, D.; Schmidt, T.C.; Neusüß, C. Non-targeted LC-MS and CE-MS for biomarker discovery in bioreactors: Influence of separation, mass spectrometry and data processing tools. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 798, 149012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, X.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Lin, P.; Lin, Y.; Hu, S.; Cui, L. Saliva metabolomics: A non-invasive frontier for diagnosing and managing oral diseases. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, L.; Nair, L.; Kumar, D.; Arora, M.K.; Bajaj, S.; Gadewar, M.; Mishra, S.S.; Rath, S.K.; Dubey, A.K.; Kaithwas, G.; et al. Hypoxia induced lactate acidosis modulates tumor microenvironment and lipid reprogramming to sustain the cancer cell survival. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1034205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polachini, G.M.; de Castro, T.B.; Smarra, L.F.S.; Henrique, T.; de Paula, C.H.D.; Severino, P.; Mendoza López, R.V.; Lopes Carvalho, A.; de Mattos Zeri, A.C.; Guerreiro Silva, I.D.C.; et al. Plasma metabolomics of oral squamous cell carcinomas based on NMR and MS approaches provides biomarker identification and survival prediction. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alapati, S.; Fortuna, G.; Ramage, G.; Delaney, C. Evaluation of Metabolomics as Diagnostic Targets in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review. Metabolites 2023, 13, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, T.; Washio, J.; Takahashi, T.; Echigo, S.; Takahashi, N. Glucose and glutamine metabolism in oral squamous cell carcinoma: Insight from a quantitative metabolomic approach. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2014, 118, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohshima, M.; Sugahara, K.; Kasahara, K.; Katakura, A. Metabolomic analysis of the saliva of Japanese patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 37, 2727–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Su, W.; Wang, G.; Wang, Z. The Kynurenine Pathway and Indole Pathway in Tryptophan Metabolism Influence Tumor Progression. Cancer Med. 2025, 14, e70703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platten, M.; Wick, W.; Van den Eynde, B.J. Tryptophan catabolism in cancer: Beyond IDO and tryptophan depletion. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 5435–5440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijakowski, K.; Gruszczyński, D.; Kopała, D.; Surdacka, A. Salivary Metabolomics for Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Diagnosis: A Systematic Review. Metabolites 2022, 12, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmedo, I.; Martínez, D.; Carrasco-Rojas, J.; Jara, J.A. Mitochondria in oral cancer stem cells: Unraveling the potential drug targets for new and old drugs. Life Sci. 2023, 331, 122065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panneerselvam, K.; Ishikawa, S.; Krishnan, R.; Sugimoto, M. Salivary Metabolomics for Oral Cancer Detection: A Narrative Review. Metabolites 2022, 12, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, M.; Wong, D.T.; Hirayama, A.; Soga, T.; Tomita, M. Capillary electrophoresis mass spectrometry-based saliva metabolomics identified oral, breast and pancreatic cancer-specific profiles. Metabolomics 2010, 6, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonelli, R.; Setti, G.; Treister, N.S.; Pertinhez, T.A.; Ferrari, E.; Gallo, M.; Bologna-Molina, R.; Vescovi, P.; Meleti, M. Salivary Metabolomics in Oral Cancer: A Systematic Review. Oral Oncol. Rep. 2024, 11, 100657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.; Liu, Y.; Yin, P.; Zeng, Z.; Huang, Q.; Kong, H.; Lu, X.; Zhong, L.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, G. Study of induction chemotherapy efficacy in oral squamous cell carcinoma using pseudotargeted metabolomics. J. Proteome Res. 2014, 13, 1994–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, S.; Sugimoto, M.; Konta, T.; Kitabatake, K.; Ueda, S.; Edamatsu, K.; Okuyama, N.; Yusa, K.; Iino, M. Salivary Metabolomics for Prognosis of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2022, 11, 789248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wang, X.; Ding, Y.; Xiao, B.; Wang, X.; Ali, M.M.; Ma, L.; Xie, Z.; Gu, Z.; Chen, G.; et al. Proteomic and phosphoproteomic landscape of salivary extracellular vesicles to assess OSCC therapeutical outcomes. Proteomics 2023, 23, e2200319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, F.; Curcio, H.F.Q.; da Silva Fidalgo, T.K. Periodontal disease metabolomics signatures from different biofluids: A systematic review. Metabolomics 2022, 18, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citterio, F.; Romano, F.; Meoni, G.; Iaderosa, G.; Grossi, S.; Sobrero, A.; Dego, F.; Corana, M.; Berta, G.N.; Tenori, L.; et al. Changes in the Salivary Metabolic Profile of Generalized Periodontitis Patients after Non-surgical Periodontal Therapy: A Metabolomic Analysis Using Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basic, A.; Dahlén, G. Microbial metabolites in the pathogenesis of periodontal diseases: A narrative review. Front. Oral Health 2023, 4, 1210200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Schipper, H.M.; Velly, A.M.; Mohit, S.; Gornitsky, M. Salivary biomarkers of oxidative stress: A critical review. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 85, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóthová, Ľ.; Kamodyová, N.; Červenka, T.; Celec, P. Salivary markers of oxidative stress in oral diseases. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2015, 5, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, F.; Meoni, G.; Manavella, V.; Baima, G.; Tenori, L.; Cacciatore, S.; Aimetti, M. Analysis of salivary phenotypes of generalized aggressive and chronic periodontitis through nuclear magnetic resonance-based metabolomics. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, 1452–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téllez, N.; Aguilera, N.; Quiñónez, B.; Silva, E.; González, L.E.; Hernández, L. Arginine and glutamate levels in the gingival crevicular fluid from patients with chronic periodontitis. Braz. Dent. J. 2008, 19, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baima, G.; Corana, M.; Iaderosa, G.; Romano, F.; Citterio, F.; Meoni, G.; Tenori, L.; Aimetti, M. Metabolomics of gingival crevicular fluid to identify biomarkers for periodontitis: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Periodontal Res. 2021, 56, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekaran, I.J.; Krishnamurthy, H.K.; Bosco, J.; Jayaraman, V.; Krishna, K.; Wang, T.; Bei, K. Oral Microbiome: A Review of Its Impact on Oral and Systemic Health. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, P.D.; Zaura, E. Dental biofilm: Ecological interactions in health and disease. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2017, 44, S12–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, P.E.; Coffman, J.A.; Garcia-Godoy, F. Oral Pathogens’ Substantial Burden on Cancer, Cardiovascular Diseases, Alzheimer’s, Diabetes, and Other Systemic Diseases: A Public Health Crisis—A Comprehensive Review. Pathogens 2024, 13, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, J.; Pan, D.; Wang, X.; Xu, Y.; Yan, J.; Wang, L.; Yang, X.; Yang, M.; Liu, G.P. Applications of multi-omics analysis in human diseases. MedComm 2023, 4, e315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasin, Y.; Seldin, M.; Lusis, A. Multi-omics approaches to disease. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Sharma, G.; Karmakar, S.; Banerjee, S. Multi-OMICS approaches in cancer biology: New era in cancer therapy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2024, 1870, 167120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, L.; Yuanyuan, L.; Zhiqiang, W.; Manlin, F.; Chenrui, H.; Ouyang, Z.; Jiatong, L.; Xi, H.; Zhihua, L. Multi-omics study of key genes, metabolites, and pathways of periodontitis. Arch. Oral Biol. 2023, 153, 105720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldner-Busztin, D.; Firbas Nisantzis, P.; Edmunds, S.J.; Boza, G.; Racimo, F.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Limborg, M.T.; Lahti, L.; de Polavieja, G.G. Dealing with dimensionality: The application of machine learning to multi-omics data. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btad021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandereyken, K.; Sifrim, A.; Thienpont, B.; Wouters, J.; van den Oord, J.; Aibar, S.; Potier, D.; Aerts, S. Methods and applications for single-cell and spatial multi-omics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2023, 24, 494–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, M.; Polizzi, A.; Blasi, A.; Grippaudo, C.; Isola, G. Untargeted Salivary Metabolomics and Proteomics: Paving the Way for Early Detection of Periodontitis. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ye, S.Y.; Xu, X.D.; Liu, Q.; Ma, F.; Yu, X.; Luo, Y.H.; Chen, L.L.; Zeng, X. Multiomics analysis reveals the genetic and metabolic characteristics associated with the low prevalence of dental caries. J. Oral Microbiol. 2023, 15, 2277271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.S.; Huang, S.; Chen, Z.; Chu, C.H.; Takahashi, N.; Yu, O.Y. Application of omics technologies in cariology research: A critical review with bibliometric analysis. J. Dent. 2024, 141, 104801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, U.; Dey, A.; Chandel, A.K.S.; Sanyal, R.; Mishra, A.; Pandey, D.K.; De Falco, V.; Upadhyay, A.; Kandimalla, R.; Chaudhary, A.; et al. Cancer chemotherapy and beyond: Current status, drug candidates, associated risks and progress in targeted therapeutics. Genes Dis. 2022, 10, 1367–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Oral Disease | Representative Genomic Markers | Type of Alteration | Functional/Clinical Significance | Type of Evidence/Clinical Relevance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OSCC | TP53, CDKN2A (p16INK4a), NOTCH1, FAT1, CASP8, HRAS, PTPRT, ARID2, TERT, PIK3CA, PTEN, CD274 (PD-L1), JAK1/2 | Somatic mutations, epigenetic alteration, amplifications/deletions, promoter mutations, Pathway-level dysregulation | Loss of tumor suppression, activation of oncogenic pathways, genomic instability, increased proliferation, invasion, metastasis, immune evasion, poor prognosis, therapeutic targeting, prognostic biomarker potential | p16: established clinical biomarker (for HPV). Other markers: discovery-phase omics studies (genomic profiling) | [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,16,17,18] |

| OSCC (HPV+) | HPV16 E6/E7, CDKN2A/p16 | Viral oncogenic integration | Inactivation of p53 and pRB, p16 overexpression, genomic stability, favorable prognosis, predictive marker for HPV-driven subtype | Established clinical biomarker (routine diagnostic test) | [13,14,15] |

| Dental caries | WNT10A, DEFB1, AQP5, TAS1R2, TAS1R3, AMELX, MMP20 | Genetic variants, SNPs, mutations, epigenetic modifications | Impaired enamel formation, defective mineralization, altered salivary composition, dysregulated immune defense, modified taste perception, increased sugar intake, higher caries susceptibility, potential for personalized prevention | Discovery-phase omics studies; preliminary clinical studies | [21,22,3,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33] |

| Periodontitis | SIGLEC5, IL1α/β, IL6, TNF-α, TLR4, SIGLEC5, MMP2/8/9, VDR, GLP1R | Genetic polymorphisms, SNPs, functional variants, epigenetic modifications | Exaggerated inflammatory response, impaired immune regulation, increased tissue destruction, enhanced bone resorption, altered host–microbe interactions, higher disease susceptibility, link with metabolic disorders, potential for personalized risk assessment | Discovery-phase omics studies | [34,35,36,37,38,39,40] |

| Oral Disease | Transcriptomic Biomarkers | Molecular Alteration | Functional/Diagnostic Relevance | Type of Evidence/Clinical Relevance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autoimmune diseases (OLP, PV, MMP, SS) | IRF8, TYROBP, FCER1G, PHGDH, LINC01588, CXCL10, IFI44L, IFIT3, MX1 | Upregulated immune and IFN-response genes | Pathogenic Immune Dysregulation & T-cell Exhaustion, Therapy Response & Immune Regulation | Discovery-phase omics studies | [55,53,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63] |

| OSCC | VIM, ZEB1, TWIST1, CXCL12, IL6, TGF-β, IFNG, PD-1, LAG3, TIGIT, miR-21, miR-125a, miR-31 | Up-regulation and differential gene expression, miRNA overexpression | EMT, CAF activation, immune evasion, therapy response, potential non-invasive early diagnostic biomarkers | Discovery-phase omics studies; no clinical validation | [65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77] |

| Oral Disease | Proteomic Biomarkers | Molecular Alteration | Functional/Clinical Significance | Type of Evidence/Clinical Relevance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OSCC | EGFR, Hsp70, Hsp27, Annexin A1, α-enolase, Cyclophilin A, CKs, CFH, FGA, SERPINA1 | Overexpression in saliva, tissue, EVs | Cell proliferation, stress response, diagnostic panel candidates | Discovery-phase omics studies | [91,92,93,94,95,96,90,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105] |

| Periodontitis | MMP-8, MMP-9, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, PGE2, haptoglobin, S100A8, lysozyme C, resistin | Overexpression in GCF and saliva | Inflammation, bone resorption, response to therapy | Discovery-phase omics studies; preliminary clinical studies for evaluating treatment outcomes | [110,111,112,113,114,115] |

| Oral Disease | Metabolomic Biomarkers | Metabolic Alteration/Pathway | Diagnostic/Functional Interpretation | Type of Evidence/Clinical Relevance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OSCC | Lactate, pyruvate, glucose-6-phosphate, glutamine, glutamate, valine, leucine, kynurenine, succinate, citrate, fumarate, malate | Warburg effect, amino acid metabolism, TCA cycle | Diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers, therapeutic targets | Discovery-phase omics studies; no clinical validation | [123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137] |

| Periodontitis | Lactate, SCFAs (acetate, butyrate), proline, phenylalanine, tyrosine, glutamate, arginine, TBARS, 8-OHdG | Dysbiosis, collagen degradation, oxidative stress | Reflect inflammatory status and microbial activity | Established markers of oxidative stress from preclinical/in vitro evidence; no clinical validation | [138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lollobrigida, M.; Mazzucchi, G.; De Biase, A. Omics Sciences in Dentistry: A Narrative Review on Diagnostic and Therapeutic Applications for Prevalent Oral Diseases. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3086. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233086

Lollobrigida M, Mazzucchi G, De Biase A. Omics Sciences in Dentistry: A Narrative Review on Diagnostic and Therapeutic Applications for Prevalent Oral Diseases. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(23):3086. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233086

Chicago/Turabian StyleLollobrigida, Marco, Giulia Mazzucchi, and Alberto De Biase. 2025. "Omics Sciences in Dentistry: A Narrative Review on Diagnostic and Therapeutic Applications for Prevalent Oral Diseases" Diagnostics 15, no. 23: 3086. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233086

APA StyleLollobrigida, M., Mazzucchi, G., & De Biase, A. (2025). Omics Sciences in Dentistry: A Narrative Review on Diagnostic and Therapeutic Applications for Prevalent Oral Diseases. Diagnostics, 15(23), 3086. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233086