Segmental Non-Mass Enhancement Features in Breast Magnetic Resonance Imaging: A Multicenter Retrospective Study of Histopathologic Correlations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

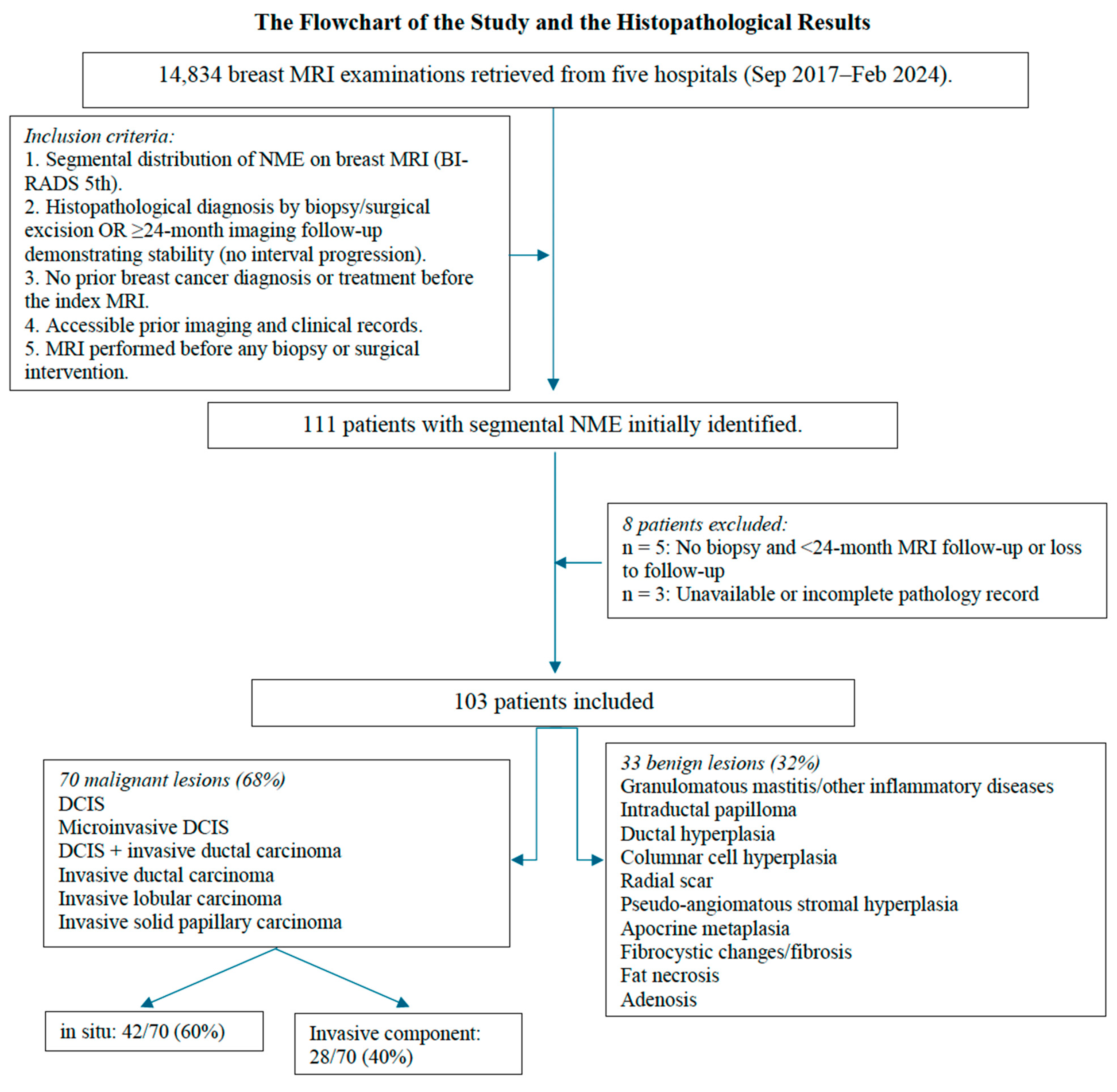

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. MRI Acquisition Protocol and Image Analysis

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient and Histopathological Characteristics

3.2. Multiparametric Breast MRI Findings

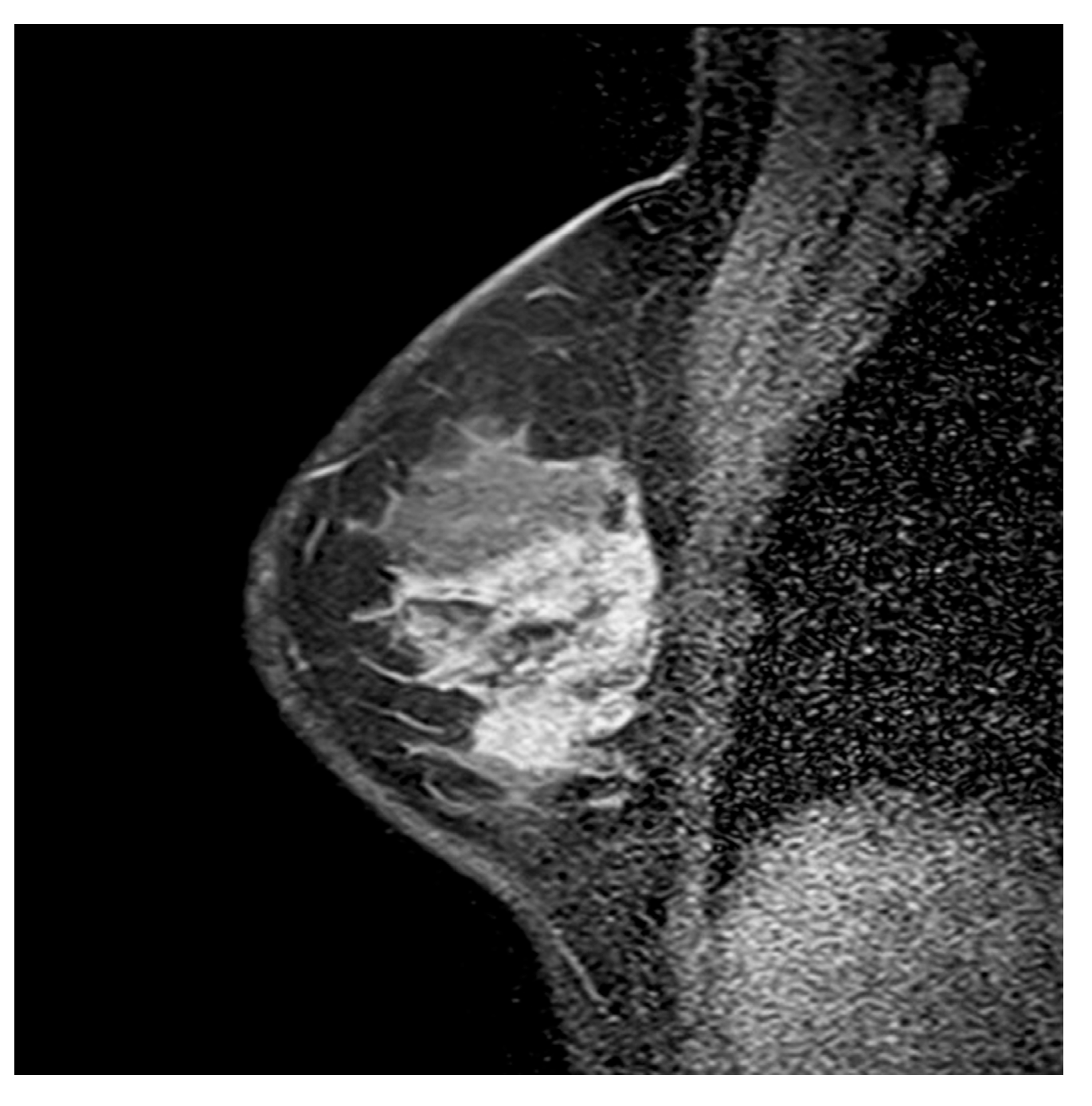

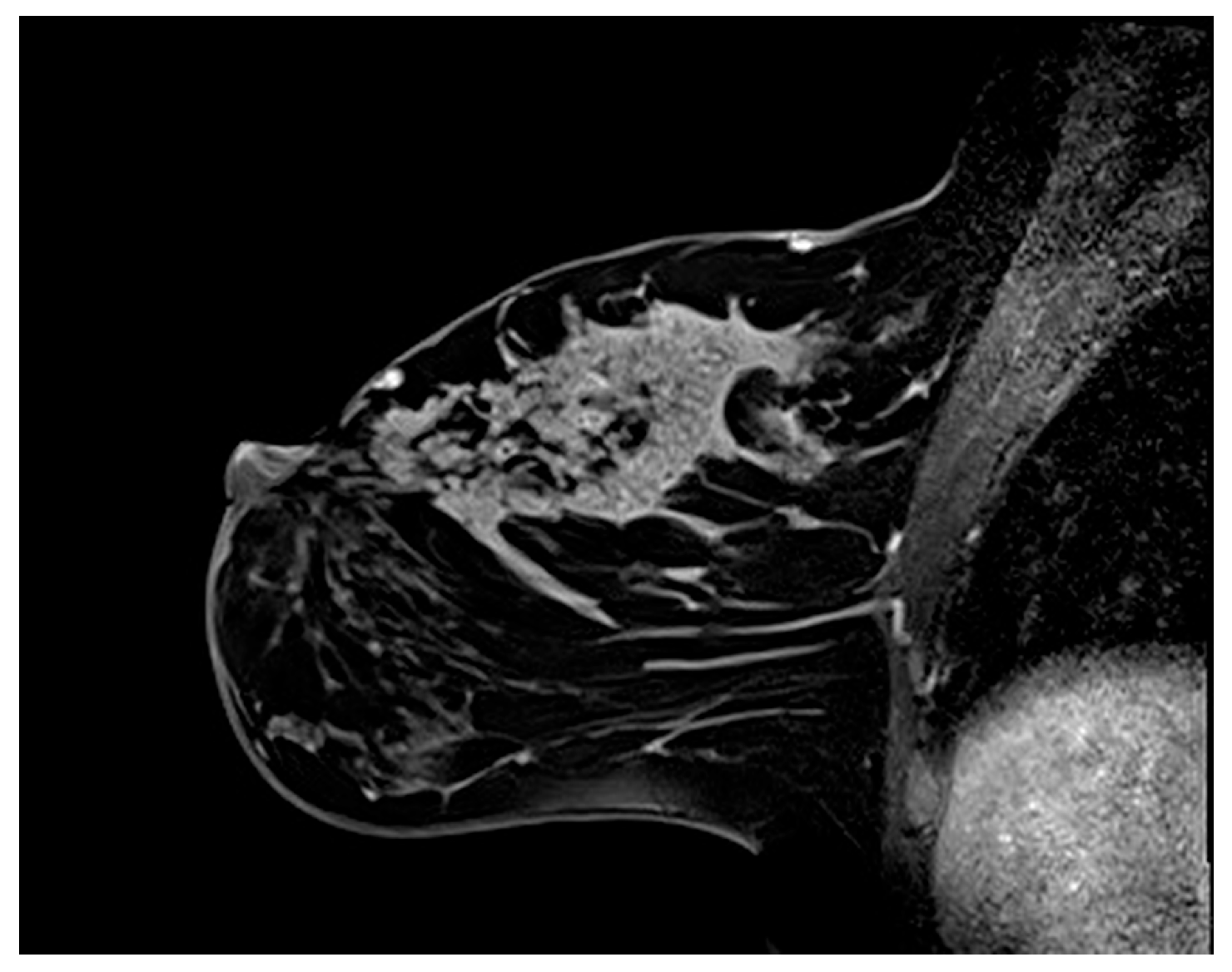

3.2.1. Internal Enhancement Patterns

3.2.2. Mixed Enhancement Patterns

3.2.3. STIR and Diffusion MRI Findings

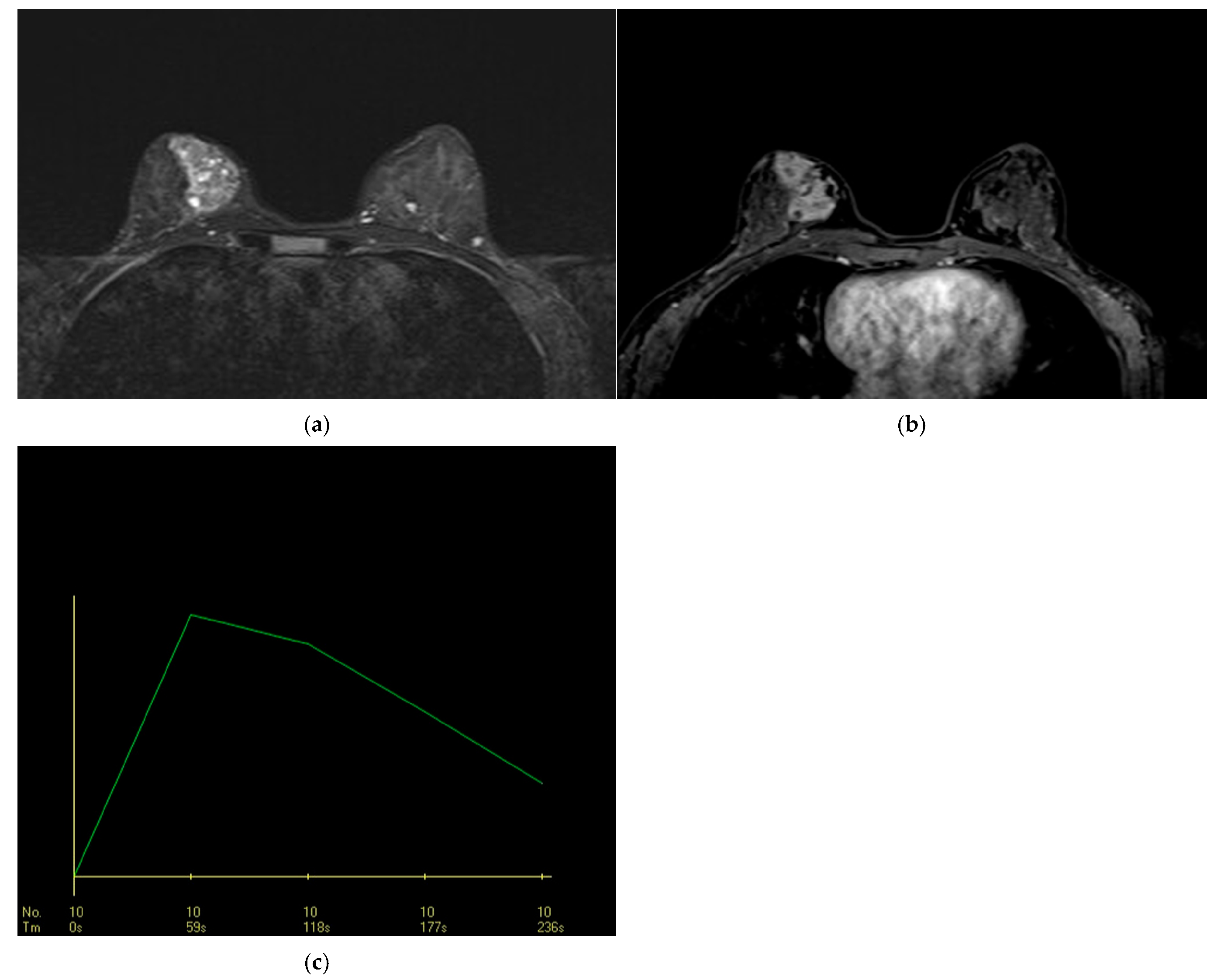

3.2.4. DCE-MRI Kinetic Features

3.2.5. Inter-Reader Agreement and Consensus Reading

3.3. Multivariate Analysis

3.4. Correlation with Invasion

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACR | American College of Radiology |

| BI-RADS | Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System |

| CRE | clustered ring enhancement |

| DCE | dynamic contrast-enhanced |

| DCIS | ductal carcinoma in situ |

| DWI | diffusion-weighted imaging |

| IDC | invasive ductal carcinoma |

| IEP | internal enhancement pattern |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| NME | nonmass enhancement |

| OR | odds ratio |

| PPV | positive predictive value |

| STIR | short tau inversion recovery |

| TIC | time–intensity curve |

References

- American College of Radiology (ACR). ACR BI-RADS-ACR; American College of Radiology: Reston, VA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chikarmane, S.A.; Michaels, A.Y.; Giess, C.S. Revisiting Nonmass Enhancement in Breast MRI: Analysis of Outcomes and Follow-Up Using the Updated BI-RADS Atlas. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2017, 209, 1178–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Li, Y.; Chen, S.-L.; Chen, Q. Non-Mass Enhancement Breast Lesions: MRI Findings and Associations with Malignancy. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.-X.; Ji, X.; Feng, L.-L.; Zheng, L.; Zhou, X.-Q.; Wu, Q.; Chen, X. Significant MRI Indicators of Malignancy for Breast Non-Mass Enhancement. J. X-Ray Sci. Technol. 2017, 25, 1033–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arian, A.; Athar, M.M.T.; Nouri, S.; Ghorani, H.; Khalaj, F.; Hejazian, S.S.; Shaghaghi, S.; Beheshti, R. Role of Breast MRI BI-RADS Descriptors in Discrimination of Non-Mass Enhancement Lesion: A Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Radiol. 2025, 185, 111996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhe, X.; Tang, M.; Lei, X.; Zhang, X. Meta-Analysis of Dynamic Contrast Enhancement and Diffusion-Weighted MRI for Differentiation of Benign from Malignant Non-Mass Enhancement Breast Lesions. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1332783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarigan, V.N.; Kusumaningtyas, N.; Supit, N.I.S.H.; Sanjaya, E.; Chandra, M.; Sulay, C.B.H.; Octavius, G.S. An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Accuracy of Dynamic Contrast Enhancement and Diffusion-Weighted MRI in Differentiating Benign and Malignant Non-Mass Enhancement Lesions. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, H. The MRI Characteristics of Non-Mass Enhancement Lesions of the Breast: Associations with Malignancy. Br. J. Radiol. 2019, 92, 20180464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Faria Castro Fleury, E.; Castro, C.; do Amaral, M.S.C.; Roveda Junior, D. Management of Non-Mass Enhancement at Breast Magnetic Resonance in Screening Settings Referred for Magnetic Resonance-Guided Biopsy. Breast Cancer Basic Clin. Res. 2022, 16, 11782234221095897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, K.; Mori, M.; Fujioka, T.; Watanabe, K.; Ito, Y. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Diagnosis of Non-Mass Enhancement of the Breast. J. Med. Ultrason. 2023, 50, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesio, L.; Di Pastena, F.; Gigli, S.; D’ambrosio, I.; Aceti, A.; Pontico, M.; Manganaro, L.; Porfiri, L.M.; Tardioli, S. Non Mass-like Enhancement Categories Detected by Breast MRI and Histological Findings. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 18, 910–917. [Google Scholar]

- Machida, Y.; Shimauchi, A.; Tozaki, M.; Kuroki, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Fukuma, E. Descriptors of Malignant Non-Mass Enhancement of Breast MRI: Their Correlation to the Presence of Invasion. Acad. Radiol. 2016, 23, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimauchi, A.; Ota, H.; Machida, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Satani, N.; Mori, N.; Takase, K.; Tozaki, M. Morphology Evaluation of Nonmass Enhancement on Breast MRI: Effect of a Three-Step Interpretation Model for Readers’ Performances and Biopsy Recommendations. Eur. J. Radiol. 2016, 85, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avendano, D.; Marino, M.A.; Leithner, D.; Thakur, S.; Bernard-Davila, B.; Martinez, D.F.; Helbich, T.H.; Morris, E.A.; Jochelson, M.S.; Baltzer, P.A.T.; et al. Limited Role of DWI with Apparent Diffusion Coefficient Mapping in Breast Lesions Presenting as Non-Mass Enhancement on Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced MRI. Breast Cancer Res. BCR 2019, 21, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltzer, P.A.T.; Dietzel, M.; Kaiser, W.A. Nonmass Lesions in Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Breast: Additional T2-Weighted Images Improve Diagnostic Accuracy. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 2011, 35, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Yang, Z.; Fan, C.; Qin, Y.; Tang, C.; Yin, T.; Ai, T.; Xia, L. Contrasts Between Diffusion-Weighted Imaging and Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced MR in Diagnosing Malignancies of Breast Nonmass Enhancement Lesions Based on Morphologic Assessment. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2023, 58, 963–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickel, H.; Pinker, K.; Polanec, S.; Magometschnigg, H.; Wengert, G.; Spick, C.; Bogner, W.; Bago-Horvath, Z.; Helbich, T.H.; Baltzer, P. Diffusion-Weighted Imaging of Breast Lesions: Region-of-Interest Placement and Different ADC Parameters Influence Apparent Diffusion Coefficient Values. Eur. Radiol. 2017, 27, 1883–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, M.; Liu, D.; Sheng, F.; Cai, J. Differential Diagnosis of Benign and Malignant Breast Papillary Neoplasms on MRI With Non-Mass Enhancement. Acad. Radiol. 2023, 30 (Suppl. S2), S127–S132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asada, T.; Yamada, T.; Kanemaki, Y.; Fujiwara, K.; Okamoto, S.; Nakajima, Y. Grading System to Categorize Breast MRI Using BI-RADS 5th Edition: A Statistical Study of Non-Mass Enhancement Descriptors in Terms of Probability of Malignancy. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2018, 36, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydin, H.; Guner, B.; Bostanci, I.E.; Cosar, Z.S.; Kiziltepe, F.T.; Aribas, B.K.; Bozdogan, N. Unusual Presentation of Tubular Breast Carcinoma as Non-Mass Enhancement. Egypt. J. Radiol. Nucl. Med. 2018, 49, 281–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadashvili, T.; Ghosh, E.; Fein-Zachary, V.; Mehta, T.S.; Venkataraman, S.; Dialani, V.; Slanetz, P.J. Nonmass Enhancement on Breast MRI: Review of Patterns With Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation and Discussion of Management. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2015, 204, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunkiewicz, M.; Forte, S.; Freiwald, B.; Singer, G.; Leo, C.; Kubik-Huch, R.A. Interobserver Variability and Likelihood of Malignancy for Fifth Edition BI-RADS MRI Descriptors in Non-Mass Breast Lesions. Eur. Radiol. 2020, 30, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milosevic, Z.C.; Nadrljanski, M.M.; Milovanovic, Z.M.; Gusic, N.Z.; Vucicevic, S.S.; Radulovic, O.S. Breast Dynamic Contrast Enhanced MRI: Fibrocystic Changes Presenting as a Non-Mass Enhancement Mimicking Malignancy. Radiol. Oncol. 2017, 51, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, S.Y.; Han, B.-K.; Ko, E.Y.; Shin, J.H.; Hwang, J.-Y.; Nam, M. MR Features to Suggest Microinvasive Ductal Carcinoma of the Breast: Can It Be Differentiated from Pure DCIS? Acta Radiol. 2013, 54, 742–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Benign Lesions (n = 33, 32%) n (%) | Malignant Lesions (n = 70, 68%) n (%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal enhancement pattern * | 0.002 * | ||

| Clustered ring * | 4 (12.1%) | 28 (40%) | 0.004 * |

| Clumped | 10 (30.3%) | 20 (28.6%) | 0.857 |

| Heterogeneous * | 18 (54.6%) | 15 (21.4%) | 0.001 * |

| Homogeneous | 1 (3.0%) | 7 (10.0%) | 0.431 ** |

| Mixed enhancement pattern (n = 75) | |||

| Present | 4 (18.2%) | 22 (41.5%) | 0.053 |

| Absent | 18 (81.8%) | 31 (58.5%) | |

| Dynamic curve in the initial phase * | <0.001 * | ||

| Slow * | 20 (60.6%) | 12 (17.1%) | <0.001 * |

| Moderate | 7 (21.2%) | 16 (22.9%) | 0.852 |

| Rapid * | 6 (18.2%) | 42 (60%) | <0.001 * |

| Dynamic curve in the delayed phase * | 0.009 * | ||

| Persistent | 15 (45.5%) | 17 (24.3%) | 0.030 * |

| Plateau | 16 (48.5%) | 31 (44.3%) | 0.690 |

| Washout | 2 (6.0%) | 22 (31.4%) | 0.004 * |

| Diffusion restriction | |||

| Present | 19 (57.6%) | 41 (64.1%) | 0.533 |

| Absent | 14 (42.4%) | 23 (35.9%) | |

| Cystic structures on the STIR images | |||

| Present | 10 (30.3%) | 18 (25.7%) | 0.625 |

| Absent | 23 (69.7%) | 52 (74.3%) |

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI for EXP(B) | p Value | OR | 95% CI for EXP(B) | p Value | |||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Internal enhancement pattern | ||||||||

| Clustered ring * | 4.833 | 1.531 | 15.258 | 0.007 * | ||||

| Clumped | 0.920 | 0.372 | 2.275 | 0.857 | ||||

| Heterogeneous * | 0.227 | 0.093 | 0.554 | 0.001 * | ||||

| Homogeneous | 3.556 | 0.419 | 30.161 | 0.245 | ||||

| Dynamic curve in the initial phase | ||||||||

| Slow * | 0.134 | 0.053 | 0.343 | 0.000 * | 0.194 | 0.049 | 0.770 | 0.020 |

| Moderate | 1.101 | 0.403 | 3.003 | 0.852 | ||||

| Rapid * | 6.750 | 2.469 | 18.451 | 0.000 * | 5.133 | 1.164 | 22.637 | 0.031 |

| Dynamic curve in the delayed phase | ||||||||

| Persistent * | 0.385 | 0.160 | 0.925 | 0.033 * | ||||

| Plateau | 0.845 | 0.368 | 1.936 | 0.690 | ||||

| Washout * | 7.104 | 1.559 | 32.363 | 0.011 * | ||||

| Mixed IEP | 3.194 | 0.949 | 10.746 | 0.061 | ||||

| Diffusion restriction | 1.314 | 0.557 | 3.100 | 0.534 | ||||

| Classification | Lesions |

|---|---|

| Benign | Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia, usual ductal hyperplasia, apocrine metaplasia, adenosis and fibrocystic changes, duct ectasia and periductal fibrosis, fibroadenoma, silicone granuloma, sclerosing adenosis, inflammation, granulomatous mastitis, post-radiation changes, normal breast tissue |

| High-risk | Atypical ductal hyperplasia, intraductal papilloma, peripheral papillomatosis, radial scar, complex sclerosing lesion, flat epithelial atypia |

| Malignant | Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), invasive ductal carcinoma, invasive lobular carcinoma, tubular carcinoma, inflammatory breast cancer, papillary carcinoma, mucinous carcinoma, apocrine carcinoma, invasive micropapillary carcinoma, Paget’s disease, glycogen-rich clear cell carcinoma |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aydin, H.; Bozkurt, C.; Hayme, S.; Bilge, A.C.; Oztekin, P.S.; Avdan Aslan, A.; Ozcan, I.; Gultekin, S.; Eren, A.; Durur Subası, I. Segmental Non-Mass Enhancement Features in Breast Magnetic Resonance Imaging: A Multicenter Retrospective Study of Histopathologic Correlations. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3084. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233084

Aydin H, Bozkurt C, Hayme S, Bilge AC, Oztekin PS, Avdan Aslan A, Ozcan I, Gultekin S, Eren A, Durur Subası I. Segmental Non-Mass Enhancement Features in Breast Magnetic Resonance Imaging: A Multicenter Retrospective Study of Histopathologic Correlations. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(23):3084. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233084

Chicago/Turabian StyleAydin, Hale, Cansu Bozkurt, Serhat Hayme, Almila Coskun Bilge, Pelin Seher Oztekin, Aydan Avdan Aslan, Irem Ozcan, Serap Gultekin, Abdulkadir Eren, and Irmak Durur Subası. 2025. "Segmental Non-Mass Enhancement Features in Breast Magnetic Resonance Imaging: A Multicenter Retrospective Study of Histopathologic Correlations" Diagnostics 15, no. 23: 3084. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233084

APA StyleAydin, H., Bozkurt, C., Hayme, S., Bilge, A. C., Oztekin, P. S., Avdan Aslan, A., Ozcan, I., Gultekin, S., Eren, A., & Durur Subası, I. (2025). Segmental Non-Mass Enhancement Features in Breast Magnetic Resonance Imaging: A Multicenter Retrospective Study of Histopathologic Correlations. Diagnostics, 15(23), 3084. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233084