Analysis of the Structural Characteristics and Psychometric Properties of the Multiple Sclerosis Intimacy and Sexuality Questionnaire (MSISQ-15): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Objectives

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Design and Protocol

3.2. Eligibility Criteria, Information Sources, and Search Strategy

3.3. Study Selection

3.4. Data Extraction and Assessment of Risk of Bias

3.5. Data Synthesis

4. Results

4.1. Study Selection Results

4.2. Study Characteristics

4.3. Risk of Bias of Included Studies

4.3.1. Structural Validity

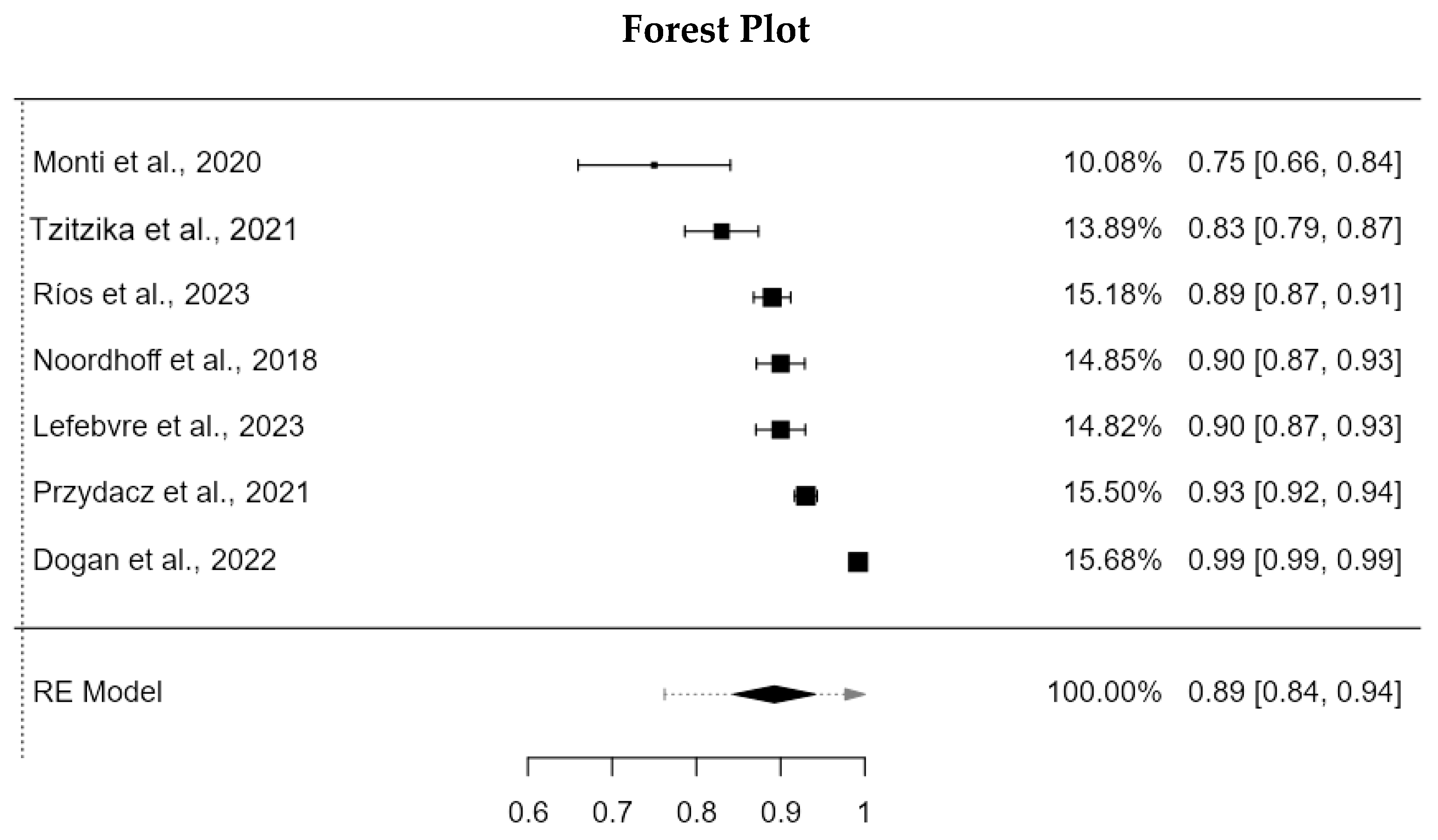

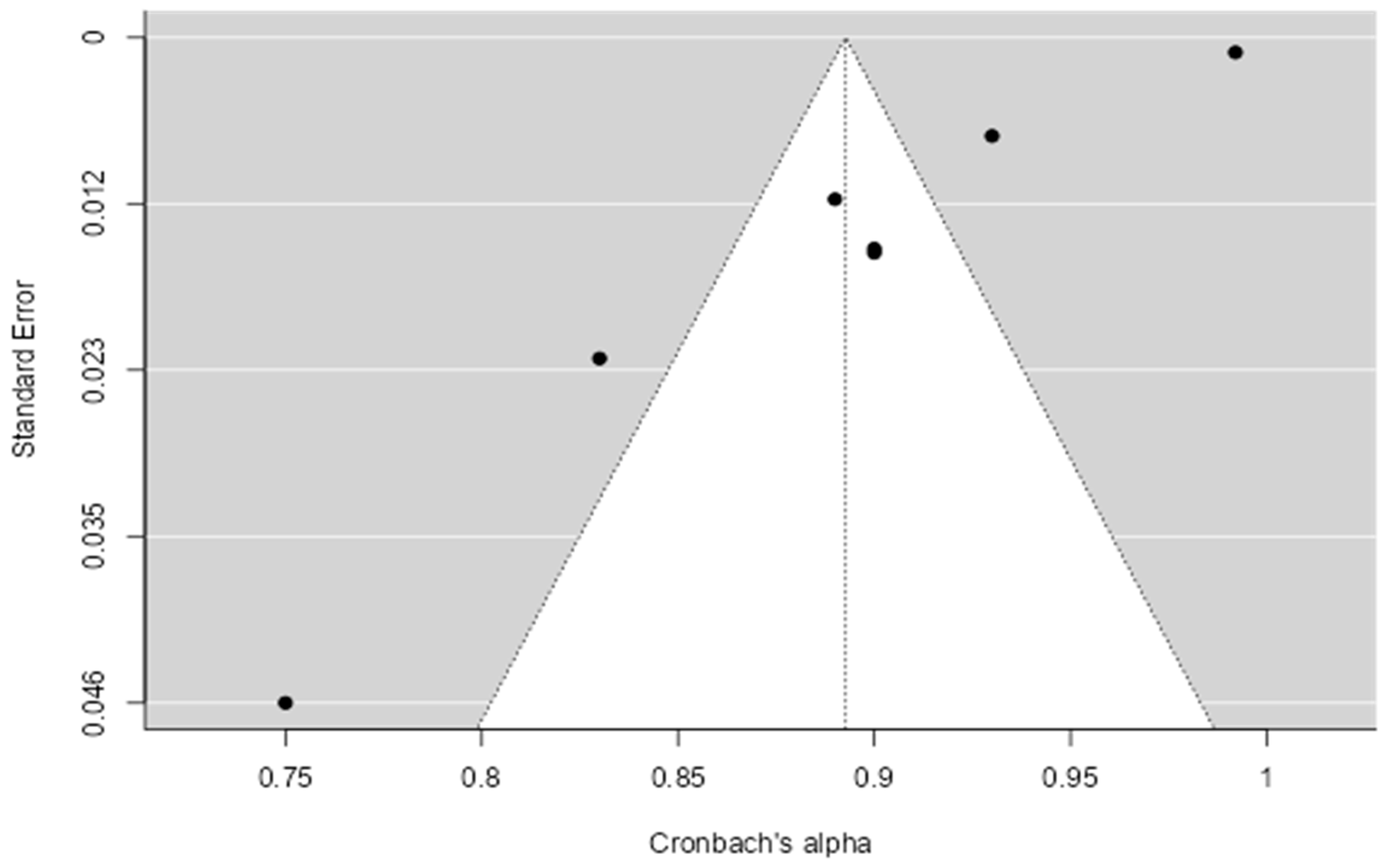

4.3.2. Internal Consistency

4.3.3. Test–Retest Reliability

4.3.4. Responsiveness

4.3.5. Methodological Quality

4.3.6. Quality of Evidence

4.4. Synthesis of Results

5. Conclusions

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Frohman, E.M. Sexual Dysfunction in Neurologic Disease. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2002, 25, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosalanejad, F.; Afrasiabifar, A.; Zoladl, M. Investigating the combined effect of pelvic floor muscle exercise and mindfulness on sexual function in women with multiple sclerosis: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2018, 32, 1340–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarto, G.; Autorino, R.; Gallo, A.; de Sio, M.; D’Armiento, M.; Perdonà, S.; Damiano, R. Quality of life in women with multiple sclerosis and overactive bladder syndrome. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2007, 18, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz Sand, I. Classification, diagnosis, and differential diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2015, 28, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashtari, F.; Rezvani, R.; Afshar, H. Sexual dysfunction in women with multiple sclerosis: Dimensions and contributory factors. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2014, 19, 228–233. [Google Scholar]

- Tepavcevic, D.; Kostic, J.; Basuroski, I.; Stojsavljevic, N.; Pekmezovic, T.; Drulovic, J. The impact of sexual dysfunction on the quality of life measured by MSQoL-54 in patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2008, 14, 1131–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorzon, M.; Zivadinov, R.; Monti Bragadin, L.; Moretti, R.; de Masi, R.; Nasuelli, D.; Cazzato, G. Sexual dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: A 2-year follow-up study. J. Neurol. Sci. 2001, 187, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorzon, M.; Zivadinov, R.; Bosco, A.; Bragadin, L.M.; Moretti, R.; Bonfigli, L.; Morassi, P.; Iona, L.G.; Cazzato, G. Sexual dysfunction in multiple sderosis: A case-control study. 1. Frequency and comparison of groups. Mult. Scler. J. 1999, 5, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, P.M.; Fowler, C.J.; Maas, C.P. Sexual function in men and women with neurological disorders. Lancet 2007, 369, 512–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borello-France, D.; Leng, W.; O’Leary, M.; Xavier, M.; Erickson, J.; Chancellor, M.B.; Cannon, T.W. Bladder and sexual function among women with multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2004, 10, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redelman, M.J. Sexual difficulties for persons with multiple sclerosis in New South Wales, Australia. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2009, 32, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivadinov, R.; Zorzon, M.; Bosco, A.; Bragadin, L.M.; Moretti, R.; Bonfigli, L.; Iona, L.G.; Cazzato, G. Sexual dysfunction in multiple sderosis: II. Correlation analysis. Mult. Scler. J. 1999, 5, 428–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, R.S.; Cacciola, A.; Bruschetta, D.; Milardi, D.; Quattrini, F.; Sciarrone, F.; la Rosa, G.; Bramanti, P.; Anastasi, G. Neuroanatomy and function of human sexual behavior: A neglected or unknown issue? Brain Behav. 2019, 9, e01389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyte, D.G.; Calvert, M.; van der Wees, P.J.; ten Hove, R.; Tolan, S.; Hill, J.C. An introduction to patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in physiotherapy. Physiotherapy 2015, 101, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benito-León, J.; Martínez-Martín, P.; Frades, B.; Martínez-Ginés, M.L.; de Andrés, C.; Meca-Lallana, J.E.; Antigüedad, A.; Huete-Antón, B.; Rodríguez-García, E.; Ruiz-Martínez, J. Impact of fatigue in multiple sclerosis: The Fatigue Impact Scale for Daily Use (D-FIS). Mult. Scler. J. 2007, 13, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickrey, B.G.; Hays, R.D.; Harooni, R.; Myers, L.W.; Ellison, G.W. A health-related quality of life measure for multiple sclerosis. Qual. Life Res. 1995, 4, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobart, J. The Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29): A new patient-based outcome measure. Brain 2001, 124, 962–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, F.W.; Zemon, V.; Campagnolo, D.; Marrie, R.A.; Cutter, G.; Tyry, T.; Beier, M.; Farrell, E.; Vollmer, T.; Schairer, L. The Multiple Sclerosis Intimacy and Sexuality Questionnaire—Re-validation and development of a 15-item version with a large US sample. Mult. Scler. J. 2013, 19, 1197–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, H.; Abakay, H.; Tekin, G.; Saçmaci, H.; Goksuluk, M.B.; Ozengin, N. The Multiple Sclerosis Intimacy and Sexuality Questionnaire (MSISQ): Validation of the Turkish version in patient with multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2022, 64, 103965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, S.; Houot, M.; Delgadillo, D.; Cantal Dupart, M.D.; Varin, D.; Papeix, C.; Sevin, M.; Bourmaleau, J.; Laigle-Donadey, F.; Jovic, L. Validation of the French version of the Multiple Sclerosis Intimacy and Sexuality Questionnaire 15 Tools which help nurse for assessing the effect of perceived multiple sclerosis symptoms on sexual activity and satisfaction. Nurs. Open 2023, 10, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti, M.; Marquez, M.A.; Berardi, A.; Tofani, M.; Valente, D.; Galeoto, G. The Multiple Sclerosis Intimacy and Sexuality Questionnaire (MSISQ-15): Validation of the Italian version for individuals with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2020, 58, 1128–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noordhoff, T.C.; Scheepe, J.R.; ’t Hoen, L.A.; Sluis, T.A.R.; Blok, B.F.M. The Multiple Sclerosis Intimacy and Sexuality Questionnaire (MSISQ-15): Validation of the Dutch version in patients with multiple sclerosis and spinal cord injury. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2018, 37, 2867–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przydacz, M.; Golabek, T.; Dudek, P.; Chlosta, P. The Multiple Sclerosis Intimacy and Sexuality Questionnaire (MSISQ-15): Translation, adaptation and validation of the Polish version for patients with multiple sclerosis and spinal cord injury. BMC Neurol. 2021, 21, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzitzika, M.; Daoultzis, C.C.; Konstantinidis, C.; Kordoutis, P. The Multiple Sclerosis Intimacy and Sexuality Questionnaire (MSISQ-15): Validation and Cross-cultural Adaptation of the Greek Version in MS Patients. Sex. Disabil. 2021, 39, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos, A.E.; Cabañero-Martínez, M.J.; Escribano, S.; Foley, F.; García-Sanjuán, S. Validation and cross-cultural adaptation of the Multiple Sclerosis Intimacy and Sexuality Questionnaire-15 (MSISQ-15) into Spanish. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokkink, L.B.; Prinsen, C.A.C.; Bouter, L.M.; Vet HCWde Terwee, C.B. The COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) and how to select an outcome measurement instrument. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2016, 20, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinsen, C.A.C.; Mokkink, L.B.; Bouter, L.M.; Alonso, J.; Patrick, D.L.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1147–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinsen, C.A.C.; Vohra, S.; Rose, M.R.; Boers, M.; Tugwell, P.; Clarke, M.; Williamson, P.R.; Terwee, C.B. How to select outcome measurement instruments for outcomes included in a “Core Outcome Set”—A practical guideline. Trials 2016, 17, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terwee, C.B.; Bot, S.D.M.; de Boer, M.R.; van der Windt, D.A.W.M.; Knol, D.L.; Dekker, J.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C.W. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2007, 60, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguayo-Albasini, J.L.; Flores-Pastor, B.; Soria-Aledo, V. Sistema GRADE: Clasificación de la calidad de la evidencia y graduación de la fuerza de la recomendación. Cir. Esp. 2014, 92, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Questionnaire/Author, Year of Publication/ Version | Population/ Sample Size, Age, Group | Affected and Control Group | Setting/ Geographical Location | Target Population and Time Since Diagnosis | Number of Subjects–Phase Pilotage | Number of Subjects Per Item |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Multiple Sclerosis Intimacy and Sexuality Questionnaire (MSISQ-15): Validation of the Dutch version in patients with multiple sclerosis and spinal cord injury/Noordhoff et al., 2018/Dutch version [22] | n = 102 SCI: 53 MS: 49 Age: SCI: 41.3 ± 11.9 MS: 46.0 ± 10.1 Sex: SCI: Men: 12 ± 22.6 Women: 41 ± 77.4 MS: Men: 41 (83.7) Women: 8 (16.3) | AG: 102 CG: 50 | NR | SCI and MS SCI: 10.1 ± 7.5 MS: 13.1 ± 11.7 | total: 6.8 SCI: 3.53 MS: 3.29 | |

| The Multiple Sclerosis Intimacy and Sexuality Questionnaire (MSISQ-15): validation of the Italian version for individuals with spinal cord injury/Monti et al., 2020/ Italian version [21] | n = 65 Age: 40.4 ± 11.9 Sex: Men: 47 ± 72.3 Women: 27 ± 27.7 | La Sapienza University of Rome and the Rehabilitation and Outcome Measures Assessment Association | SCI | 4.33 | ||

| The Multiple Sclerosis Intimacy and Sexuality Questionnaire (MSISQ-15): Validation and Cross-cultural Adaptation of the Greek Version in MS Patients/Tzitzika et al., 2021/Greek version [24] | n = 127 Age: MS: 45.57 ± 11.13 CG: 53.02 ± 9.36 Sex: MS: Men: 35 Women: 33 CG: Men: 34 Women: 25 | AG: 68 CG: 59 | Urology Department of the National Rehabilitation Centre of Athens | MS | 8.46 | |

| The Multiple Sclerosis Intimacy and Sexuality Questionnaire (MSISQ-15): translation, adaptation, and validation of the Polish version for patients with multiple sclerosis and spinal cord injury/Przydacz et al., 2021/Polish version [23] | n = 227 SCI: 110 MS: 117 Age: SCI: 39.2 ± 9.9 MS: 44.2 ± 9.4 Sex: SCI: Men: 98 (89.1%) Women: 12 (10.9%) MS: Men: 35 (29.9%) Women: 82 (70.1%) | CG not included | Department of Urology of the Jagiellonian University Medical College, Krakow, Poland | SCI and MS SCI: 12.9 ± 10.9 MS: 9.2 ± 8.3 | 299 test phase | total: 15.33 SCI: 7.33 MS: 7.8 |

| Validation of the French version of the Multiple Sclerosis Intimacy and Sexuality Questionnaire 15 Tools which help nurses assess the effect of perceived multiple sclerosis symptoms on sexual activity and satisfaction/Lefebvre et al., 2023/ French version [20] | n = 98 Age: 44.31 ± 11.33 Sex: Men: 30 Women: 68 | AG: 51 CG: 51 | Neurology department at the La Pitié Salpêtrière hospital in Paris, France | MS | 6.53 | |

| The Multiple Sclerosis Intimacy and Sexuality Questionnaire (MSISQ): Validation of the Turkish version in patients with multiple sclerosis/Dogan et al., 2022/Turkish version [19] | n = 130 Age: 41.77 ± 10.84 Sex: Women 100% | AG:130 | Neurology department of a university hospital | MS | 30 | 8.66 |

| Validation and cross-cultural adaptation of Multiple Sclerosis Intimacy and Sexuality Questionnaire-15 (MSISQ-15) into Spanish/Ríos et al., 2023/Spanish version [25] | n = 208 Age: 44.59 ± 9.788 Sex: Men: 73 Women: 135 | CG not included | Multiple sclerosis associations in Spain | MS 11.685 ± 8.5052 | 13.86 |

| Author/Version | Test–Retest Reliability | Internal Consistency | Construct Validity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Noordhoff et al., 2018/ Dutch version [22] | TS 0.88 (0.79–0.93) 1D 0.90 (0.84–0.94) 2D 0.75 (0.60–0.85) 3D 0.86 (0.77–0.92) | Cronbach’s α = 0.90 | Indeterminate |

| Monti et al., 2020/ Italian version [21] | NE | Cronbach’s α = 0.75 | MSISQ-15–SF-12 Mental health (r) Pearson: −0.360 MSISQ-15–SF-12 Physical health (r) Pearson: −0.219 MSISQ-15–SCIM SR Self-care (r) Pearson: −0.033 MSISQ-15–SCIM SR Management of respiration and sphincter (r) Pearson: −0.036 MSISQ-15–SCIM SR Mobility (r) Pearson: −0.003 MSISQ-15–Total SCIM SR: −0.028 |

| Tzitzika et al., 2021/ Greek version [24] | TS 0.83 1D 0.84 2D 0.77 3D 0.86 | Cronbach’s α = 0.83 | MSISQ-15–IIEF (r): −0.57 MSISQ-15–FSFI (r): −0.60 |

| Przydacz et al., 2021/ Polish version [23] | TS 0.91 (0.80–0.95) 1D 0.93 (0.82–0.97) 2D 0.78 (0.70–0.86) 3D 0.87 (0.79–0.93) | Cronbach’s α = 0.93 | MSISQ-15–IIEF-15 (r) Pearson Test phase: −0.487 MSISQ-15–IIEF-15 (r) Pearson Retest phase: −0.456 MSISQ-15–PISQ-31 (r) Pearson Test phase: −0.709 MSISQ-15–PISQ-31 (r) Pearson Retest phase: −0.688 |

| Lefebvre et al., 2023/ French version [20] | TS 0.90 (0.63; 0.98) 1D 0.91 (0.65; 0.98) 2D 0.30 (−0.24; 0.76) 3D 0.93 (0.74; 0.98) | Cronbach’s α = 0.90 | Indeterminate |

| Dogan et al., 2022/ Turkish version [19] | TS 0.998 1D 0.992 2D 0.990 3D 0.994 | Cronbach’s α = 0.992 | MSISQ-15–MSQOL-54 (r) Pearson correlation 1D: −0.647; 2D: −0.706; 3D: −0.703; Total: −0.763 MSISQ-15–FSFI (r) Pearson correlation 1D: −0.776; 2D: −0.594; 3D: −0.655; Total: −0.754 MSISQ-15–PSIQ-12 (r) Pearson correlation 1D: −0.741; 2D: −0.678; 3D: −0.782; Total: −0.798 |

| Ríos et al., 2023/Spanish version [25] | NE | Cronbach’s α = 0.89 | MSISQ-15–FSH (rho) Spearman 1D: (−0.53); 2D: (−0.31); 3D: (−0.42); Total (−0.52) MSISQ-15–FSM-2 (rho) Spearman 1D: (−0.65); 2D: (−0.27); 3D: (−0.32); Total (−0.55) MSISQ-15–EAD-13 (rho) Spearman 1D: (−0.14); 2D: (−0.10); 3D: (−0.08); Total (−0.14) MSISQ-15–MusiQol (rho) Spearman 1D: (−0.25); 2D: (−0.35); 3D: (−0.38); Total (−0.039) |

| PROM | Version | Structural Validity (Rating) | Internal Consistency (Rating) | Reliability (Rating) | Measurement Error (Rating) | Hypotheses Testing (Rating) | Responsiveness (Rating) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Przydacz. et al., 2021 [23] | Polish | NR | Sufficient | Sufficient | NR | NR | NR |

| Methodological quality Risk of bias | NR | Very good | Adequate | NR | NR | NR | |

| Quality of evidence | NR | High | Moderate | NR | NR | NR | |

| Noordhoff et al., 2018 [22] | Dutch | NR | Sufficient | Sufficient | NE | Sufficient | NR |

| Methodological quality Risk of bias | NR | Very good | Doubtful | Very good | Very good | NR | |

| Quality of evidence | NR | Moderate | High | Moderate | Moderate | NR | |

| Monti et al., 2020 [21] | Italian | NR | Sufficient | Sufficient | NR | NR | NR |

| Methodological quality Risk of bias | NR | Very good | Doubtful | NR | NR | NR | |

| Quality of evidence | NR | High | Moderate | NR | NR | NR | |

| Lefebvre et al., 2023 [20] | French | NR | Sufficient | Sufficient | Sufficient | NR | NR |

| Methodological quality Risk of bias | NR | Very good | Adequate | Adequate | NR | NR | |

| Quality of evidence | NR | Moderate | Moderate | High | NR | NR | |

| Dogan et al., 2022 [19] | Turkish | NR | Sufficient | Sufficient | NE | NE | NR |

| Methodological quality Risk of bias | NR | Very good | Doubtful | Adequate | Very good | NR | |

| Quality of evidence | NR | High | High | Moderate | Moderate | NR | |

| Tzitzika et al., 2021 [24] | Greek | NR | Sufficient | Sufficient | NR | Sufficient | NE |

| Methodological quality Risk of bias | NR | Very good | Adequate | NR | Very good | Inadequate | |

| Quality of evidence | NR | High | Moderate | NR | Moderate | Moderate | |

| Ríos et al., 2023 [25] | Spanish | NR | Adequate | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Methodological quality Risk of bias | NR | Very good | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Quality of evidence | NR | Moderate | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Córdoba-Peláez, M.M.; Molina-Torres, G.; Rutkowska, A.; Rutkowski, S.; Rubio-Arias, J.Á. Analysis of the Structural Characteristics and Psychometric Properties of the Multiple Sclerosis Intimacy and Sexuality Questionnaire (MSISQ-15): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2836. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15222836

Córdoba-Peláez MM, Molina-Torres G, Rutkowska A, Rutkowski S, Rubio-Arias JÁ. Analysis of the Structural Characteristics and Psychometric Properties of the Multiple Sclerosis Intimacy and Sexuality Questionnaire (MSISQ-15): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(22):2836. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15222836

Chicago/Turabian StyleCórdoba-Peláez, Marta María, Guadalupe Molina-Torres, Anna Rutkowska, Sebastian Rutkowski, and Jacobo Á. Rubio-Arias. 2025. "Analysis of the Structural Characteristics and Psychometric Properties of the Multiple Sclerosis Intimacy and Sexuality Questionnaire (MSISQ-15): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Diagnostics 15, no. 22: 2836. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15222836

APA StyleCórdoba-Peláez, M. M., Molina-Torres, G., Rutkowska, A., Rutkowski, S., & Rubio-Arias, J. Á. (2025). Analysis of the Structural Characteristics and Psychometric Properties of the Multiple Sclerosis Intimacy and Sexuality Questionnaire (MSISQ-15): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics, 15(22), 2836. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15222836