Abstract

Background/Objectives: Mild neurocognitive disorder (mNCD) is a state of vulnerability, in which individuals exhibit cognitive deficits identified by cognitive testing, which do not interfere with their ability to independently perform in daily activities. New touchscreen tools had to be designed for cognitive assessment and had to be at an advanced stage of development but their clinical relevance is still unclear. We aimed to identify digital tools used in the diagnosis of mNCD and assess the diagnostic performance of these tools. Methods: In a systematic review, we searched 4 databases for articles (PubMed, Embase, Web of science, IEEE Xplore). From 6516 studies retrieved, we included 50 articles in the review in which a touchscreen tool was used to assess cognitive function in older adults. Study quality was assessed using the QUADAS-II scale. Data from 34 articles were appropriate for meta-analysis and were analyzed using the bivariate random-effects method (STATA software version 19). Results: The 50 articles in the review totaled 5974 participants and the 34 in the meta-analysis, 4500 participants. Pooled sensitivity and specificity were 0.81 (95%CI: 0.78 to 0.84) and 0.83 (95%CI: 0.79 to 0.86), respectively. High heterogeneity among the studies led us to examine test performance across key characteristics in a subgroup analysis. Tests that are short and self-administered on a touchscreen tablet perform as well as longer tests administered by an assessor or on a fixed device. Conclusions: Cognitive testing with a touchscreen tablet is appropriate for screening for mNCD. Further studies are needed to determine their clinical utility in screening for mNCD in primary care settings and referral to specialized care. This research received no external funding and is registered with PROSPERO under the number CRD42022358725.

1. Introduction

Mild neurocognitive disorder (mNCD) is a condition in which people experience cognitive difficulties and dysfunction which do not interfere with their ability to independently perform in daily activities. mNCD may be secondary to neurocognitive diseases like Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, vascular dementia, or others. This condition offers a window of opportunity for cognitive stimulation, treatment of symptoms, implementation of compensatory strategies and introduction of healthier lifestyle habits (diet, exercise, etc.) that may delay the onset of a major neurocognitive disorder [1]. Early diagnosis of these conditions is recommended [2], first and foremost for the personal management of the person and their family, but also to enable rapid management by specialized professionals. However, diagnosing mNCD is challenging because coping mechanisms, types of cognitive deficits, and levels of cognitive reserve vary greatly from one individual to another, resulting in considerable variation in patients’ experiences and symptoms and making it difficult to accurately diagnose this condition [2]. The mNCD and its diagnostic criteria were defined by the DSM-5, and these criteria are very close to those for mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a clinical condition very similar to mNCD, which was widely used before the emergence of mNCD [3]. Early diagnosis can also support clinical research and provide a better understanding of the mechanisms of disease progression or enable participation in clinical trials. The purpose of early diagnosis of mNCD is to slow the progression towards major NCD. Although there is no curative treatment at present, there are numerous strategies that can be implemented to prevent the onset of a major NCD, which is not without consequences for the family and caregivers, with the attendant loss of autonomy for the patient [4,5].

The diagnosis of mNCD relies on medical and neuropsychological evaluation performed in memory centers by a specialized team. Diagnostic criteria have evolved, from mild cognitive impairment (MCI), initially including only memory complaints, to mNCD defined by DSM-5 criteria that now encompasses broader cognitive complaints [3,6]. In both definitions, the person exhibits cognitive deficit identified by cognitive tests and retains autonomy in their daily life. The diagnostic process is long and tedious, often with long waiting times before the first appointment, resulting in a loss of opportunity for the patient. mNCD is insidious, and those affected do not always seek medical attention. The general practitioner (GP) is in the front line when it comes to detecting mNCD and referring to specialized centers [7]. It is therefore important to provide accessible and easy-to-use tools for primary care. Detection is not easy for primary care physicians, since no clearly defined strategy exists to identify people at risk and refer them appropriately to a memory center. The most widely used conventional tests are the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) [8] and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [9]. Both are effective in screening for major neurocognitive disorders [10], but they require training and time and are rarely used by general practitioners. In a systematic review, Chun [11] analyzed the screening tools available for MCI and found that the three most frequently used were the MoCA, the MMSE and the Clock Draw Test (CDT). According to their evaluation criteria, the Six Item Cognitive Impairment Test (6 CIT), the MoCA (with thresholds of ≤24/22/19/15.5) and the MMSE (with a threshold of ≤26) as well as the Hong Kong Brief Cognitive Test (HKBC) were the most effective. However, the authors highlighted the lack of evaluation of these new cognitive tools, with threshold values determined according to the populations and environments in which they are used. The performance of the MMSE and MoCA was compared in the meta-analysis by Pinto [10] and their accuracy in identifying mNCDs was found to be 0.780 (95% CI 0.740–0.820) and 0.883 (95% CI 0.855–0.912), respectively. Both tests have been regularly criticized for their threshold values. Thus, there is still progress to be made in identifying patients with mNCD in primary care [2,10].

Tests are progressively digitized to improve objectivity and speed, with the possibility of automated scoring, which would reduce test-taking time and make them more accessible in primary care for GPs [5,12]. In addition, digital tools make it possible to record more detailed results, such as reaction times or pressure on the screen, which are not accessible to a human assessor. Furthermore, touchscreens are more accessible and intuitive thanks to their direct input, compared to keyboard and mouse use [6,13]. In previous work, we showed good detection of major neurocognitive disorders with touchscreens, which is encouraging for primary care [14].

In the present review and meta-analysis, we aimed to investigate the use of touchscreens for screening for mild cognitive disorders comprising mNCD and MCI, in older adults. We also sought to analyze the performance of these tests in relation to the reference diagnosis.

2. Materials and Methods

The protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Review (PROSPERO CRD42022358725), and the report follow the PRISMA-DTA guidelines [15] (see checklist in Supplementary Materials).

2.1. Search Strategy

We searched four databases (Medline, Embase, Web of Science and IEEE Xplore) and included all articles published up to 31 December 2024. The last extraction was in April 2025. We used terms relating to screening or diagnosis, older adults, neurocognitive diseases, touchscreen device (see Table A1 in Appendix A). The search terms were broadened to dementia, but we selected only articles dealing with early stages, taking into account the continuum of neurocognitive diseases from MCI/mNCD to dementia. The search strategies were prepared with the help of an experienced librarian. The reference lists of all articles were manually searched to retrieve relevant studies.

2.2. Article Selection

We included articles whose participants: (i) were over 60 years of age, (ii) were classified according to the presence of mNCD/MCI determined using a conventional assessment of cognition, based on reference diagnostic criteria (Petersen, National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association; National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke/Alzheimer’s disease and related Disorders Association; Alzheimer’s Disease in neuroimaging initiative, etc.), and (iii) were examined using a novel tool using a digital touchscreen device (tactile tablet, touchscreen computer or smartphone). We did not include studies in which the results for mNCD and M-NCD were mixed and could not be analyzed separately.

2.3. Data Extraction

The first two authors independently selected relevant articles from the results of the queries in PubMed, Embase, Web of Science and IEEE Xplore. Any discrepancies were discussed among evaluators until consensus was reached. A third author was consulted in case of disagreement. Reference lists were managed using Zotero® (version 6.0.30) and Excel 2013®. Duplicates were individually checked by the two authors. Each investigator evaluated the study selection criteria independently. Reasons for exclusion were noted in Zotero and differences were resolved by discussion.

Descriptive data for each article were collected by two authors and included the descriptive characteristics of the studies, namely: country, year of publication, period of inclusion of participants, mean age of population, reference diagnostic criteria, neuropsychological tests for reference diagnosis. We also recorded the characteristics of the touchscreen test, namely: name of the new test, mode of administration (self-administered or interviewer-administered), cognitive functions assessed, duration of the new test. Sensitivity, specificity and contingency tables were also included for performance analysis in the meta-analysis. If data were missing or unclear to both investigators, they were recorded as “not specified” (NS) in the table. When the contingency table was not included in the original article, we contacted the authors to obtain it, and in the absence of a reply, we calculated the number of true positives, false positives, true negatives and false negatives with sensitivity and specificity from available data.

2.4. Quality Assessment

The quality of the included articles was assessed by two authors (NUD, FM) using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies 2 instrument (QUADAS-2) [16] which measures the risk of bias and applicability of diagnostic accuracy studies. It comprises four key domains: patient selection, index test, reference standard, flow and timing. Each domain is considered for its risk of bias and applicability, and judged as high, low or unclear.

There are no official or validated decision rules for determining whether a study is of good or poor quality. We chose to exclude articles that were not of sufficiently high quality, and for this purpose, we defined our own decision rule, namely exclusion of studies with: 2 high risks of bias; or 2 high applicability concerns; or 3 risks of unclear bias; or 2 unclear applicability concerns; or 1 unclear applicability concern and 1 high applicability concern.

2.5. Meta-Analysis

We sought to complement the information about the performance of the tools tested. To this end, we collected information on true positives, false positives, true negatives and false negatives. If the information did not appear in an article, we contacted the corresponding author to obtain it.

Meta-analysis was performed with the METADTA program [17] in STATA software (version 19), which uses the bivariate random-effects method. Inter-study heterogeneity was assessed by the I2 coefficient. We performed subgroup analyses according to the type of touchscreen used (touchscreen computer or touchscreen tablet), ease of transport (fixed or mobile device), type of questionnaire administration (rater-administered or self-administered), and test duration (brief test lasting less than 10 min, and longer test lasting more than 10 min).

3. Results

3.1. Studies Included

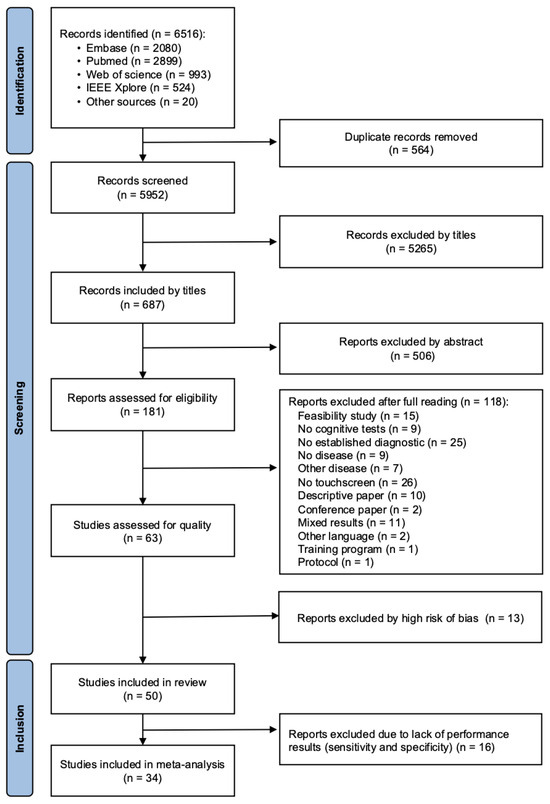

The database query yielded 6516 articles. After removal of duplicates and exclusions, 181 articles remained to be evaluated for eligibility. After the QUADAS-2 assessment, we finally included 50 studies in the review and 34 articles in the meta-analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the studies included.

3.2. Study Characteristics

We included 50 articles in the systematic review. The characteristics of the included studies are presented in Appendix A. The results are presented in 2 tables according to the digital device used, namely studies using a tactile tablet (Table A2), and studies using a computer touchscreen (Table A3). Articles were published between 2005 [18] and 2024 [19] and were performed in 17 countries located in Europe, Asia, North America and South America.

3.2.1. Participants and Settings

The studies involved 5974 participants (3368 women and 2255 men) (4 studies did not mention the participants’ sex). The number of participants by study varied from 12 [20] to 524 [21] with an average of 119. Mean age of participants was 72 years, and ranged from 53 to 81 years [22,23]. The recruitment was performed in memory centers (n = 27), in the community (n = 8), in both memory centers and the community (n = 3), hospitals (n = 14), daycare centers (n = 3), health institutions (n = 5), memory clinic and research registry (n = 2), memory clinic, research registry and community (n = 3), hospital, agencies or community advertisements (n = 2), hospital, retirement home and community (n = 1), nursing home and association (n = 1), GP offices and community (n = 1), and from a demographic surveillance record (n = 1). Three studies did not specify their recruitment methods.

3.2.2. Reference Diagnosis

The reference diagnosis of mNCD/MCI was determined by specialized professionals using reference criteria and tests or parts of tests validated and accepted by the scientific community and are detailed in Appendix A (Table A2 and Table A3). The reference diagnosis was considered as that established by a team of specialists in their own clinic, using official criteria. The studies used diagnostic criteria specific to their usual practice: Petersen’s criteria (n = 24), the National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) criteria (n = 5), the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS/ADRDA) criteria (n = 4), Jak’s criteria (n = 1), the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) criteria (n = 1), the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) criteria (n = 1), the DSM 5 criteria (n = 1), ADI criteria (n = 1), NIA-AA and DSM-5 criteria (n = 1), Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) criteria (n = 1), Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centers (ADRC) criteria (n = 1), and international working group criteria (n = 1). Eight studies did not specify diagnostic criteria but reported that a diagnosis was made following a comprehensive medical and neuropsychological evaluation. A sensitivity analysis was carried out to compare the 24 studies using Petersen’s criteria for MCI with the others, and we found no difference between them (see Figure A1 in Appendix A).

3.2.3. Touchscreen Test Procedures

A phase of learning and familiarization with the digital tool was mentioned in 16 studies and was not specified in the others.

Digital test times ranged from 2 min [24] to 2.5 h [25], 13 studies did not specify the duration and one study did not record the test duration [26]. The time needed to complete the tests was less than 5 min in 8 studies, between 10 and 15 min for 7 studies, between 15 and 30 min for 12 studies, between 30 and 60 min for 6 studies and more than an hour in 3 studies.

Thirty-one studies used a self-administered assessment (62%), 13 were assessor-administered (26%) and 6 studies (12%) did not report this information. The professionals involved were health practitioners or researchers trained in the assessments required.

The studies used tactile tablets (n = 34) and touchscreen computers (n = 16).

Forty of these devices were mobile (80%) versus 6 fixed (12%), while 4 studies did not specify the characteristics of their tool (8%).

3.2.4. Performance Results

Thirty-four studies measured the performance of their digital tests by calculating the sensitivity and specificity of their conclusion compared to the reference diagnosis. Sensitivity ranged from 0.41 (95%CI: 0.21 to 0.64) to 1.00 (95%CI: 0.74 to 1.00) [27,28]. Specificity ranged from 0.56 (95%CI: 0.28 to 0.85) to 1.00 (95%CI: 0.80 to 1.00) [26,28].

3.3. Quality Assessment

Overall, the quality of the studies assessed by QUADAS-2 was quite good [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79] (Table A4 in Appendix A). We excluded 13 studies based on our decision rule.

3.4. Meta-Analysis

3.4.1. Main Results

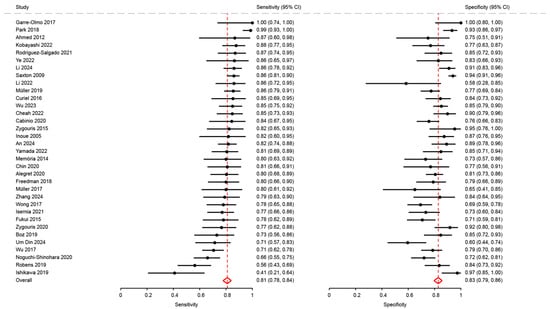

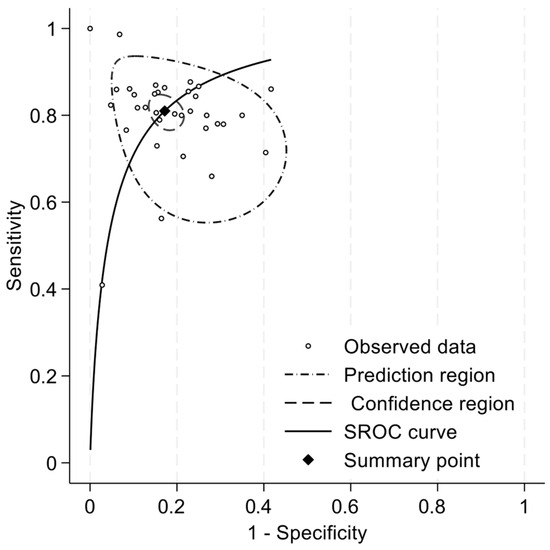

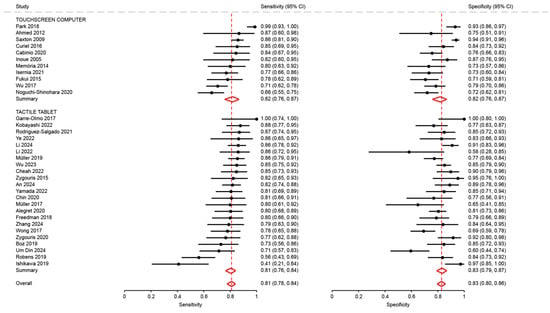

We included 34 articles in the meta-analysis, totaling 4500 participants. Pooled sensitivity and specificity were 0.81 (95%CI: 0.78 to 0.84) and 0.83 (95%CI: 0.79 to 0.86), respectively (Figure 2). The positive likelihood ratio (LR+) was 4.71 (95%CI: 3.88 to 5.73), the negative likelihood ratio (LR-) was 0.23 (95%CI: 0.19 to 0.27), and the diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) was 20.55 (95%CI: 14.66 to 28.80). The summary ROC curve indicated a high overall discriminative performance of the tests, with a summary point near the upper-left corner of the ROC space and reasonably narrow confidence region (Figure 3). I2 coefficient was 56.2, indicating that the studies were quite heterogenous.

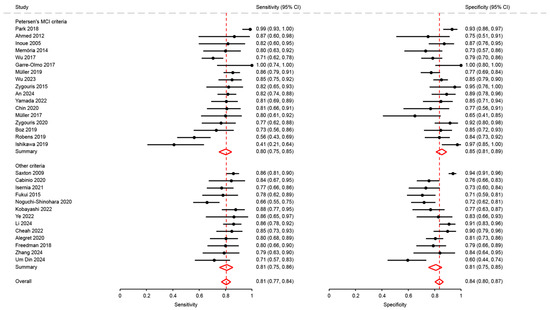

Figure 2.

Analysis of sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of mild cognitive disorders [18,21,23,26,27,28,29,31,32,34,35,36,37,38,41,43,46,47,48,50,51,53,54,62,63,64,65,66,68,69,72,74,75,76].

Figure 3.

Summary ROC curve of sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of mild cognitive disorders.

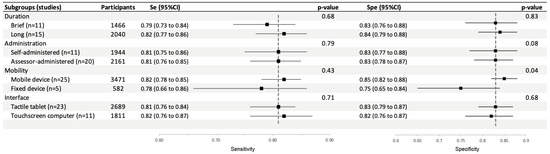

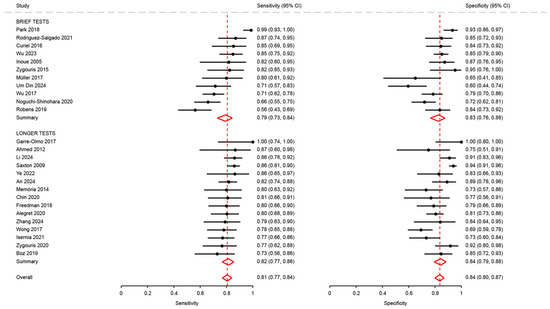

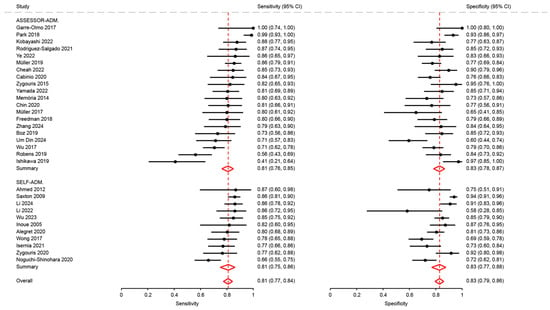

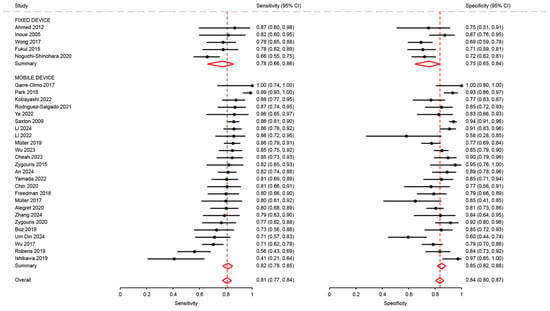

3.4.2. Subgroup Analysis

We analyzed the performance of the tests according to their procedures and device characteristics (duration, type of administration, type of touchscreen and mobility of the device) using the chi-2 test. Pooled sensitivity and specificity of these subgroups are presented in Figure 4 and the corresponding forest plots with the individual studies are shown in Appendix A (Figure A2, Figure A3, Figure A4 and Figure A5) and sections below.

Figure 4.

Subgroup analysis of pooled sensitivity and specificity of touchscreen cognitive tests for the diagnosis of mild cognitive disorders.

Duration: Brief Test vs. Longer Test

Sensitivity and specificity in studies using brief tests (0.79; 95%CI: 0.73 to 0.84 and 0.83; 95%CI: 0.76 to 0.88, respectively) were not significantly different from those of studies using longer tests (0.82; 95%CI: 0.77 to 0.86, p = 0.68, and 0.84; 95%CI: 0.79 to 0.88, p = 0.83) (Figure A2).

Type of Administration: Self or Assessor Administered

Sensitivity and specificity in studies using assessor-administered tests (0.81; 95%CI: 0.76 to 0.85 and 0.83; 95%CI: 0.78 to 0.87, respectively) were not significantly different compared to those using self-administered tests (0.81; 95%CI: 0.75 to 0.86, p = 0.79, and 0.83; 95%CI: 0.77 to 0.88, p = 0.08) (Figure A3).

Mobility: Fixed or Mobile Device

Sensitivity in studies using a mobile device were not significantly different from that of studies using a fixed device (0.82; 95%CI: 0.78 to 0.85 and 0.78; 95%CI: 0.66 to 0.86, p = 0.43). Conversely, specificity in studies using a mobile device was significantly different higher than in studies using a fixed device (0.85; 95%CI: 0.82 to 0.88 and 0.75; 95%CI: 0.65 to 0.84, p = 0.04) (Figure A4).

Type of Interface: Touchscreen Computer or Tactile Tablet

Sensitivity and specificity in studies using a tactile tablet (0.81; 95%CI: 0.76 to 0.84 and 0.83; 95%CI: 0.79 to 0.87, p = 0.71) were not significantly different from those of studies using a touchscreen computer (0.82; 95%CI: 0.76 to 0.87, and 0.82; 95%CI: 0.76 to 0.87, p = 0.68) (Figure A5).

The cognitive tests with the highest combined sensitivity and specificity are summarized in the table below (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cognitive tests with the highest pooled sensitivity and specificity.

4. Discussion

This review and meta-analysis showed that cognitive tests on touchscreen tools are appropriate to diagnose mNCD in older adults. A large variety of digital devices give satisfactory results in screening for mNCD/MCI. Although imperfect, the overall performance of touchscreen cognitive tests is similar to that of the MoCA, the reference clinical test to screen for mNCD, and several touchscreen cognitive tests outperformed it. However, the heterogeneity of methods and tools makes it difficult to compare studies, precluding any conclusion as to which one is the most effective.

The high degree of heterogeneity among the studies led us to examine test performance based on their main characteristics in a subgroup analysis. It is interesting to note that tests that are short, self-administered and conducted on a touchscreen tablet perform as well as longer tests administered by an assessor or on a fixed device. The former characteristics are very appealing for devices in clinical use, as they are simple, require little professional time and can be used on easily accessible systems.

Through our review, several tools appeared to us to be attractive, due to their good performance in diagnosing mild cognitive disorders (Table 1). Rodríguez-Salgado [54] developed the tool that combines the most practical clinical features and performance, namely the Brain Health Assessment (BHA). It consists of 4 tests: Favorites (associative memory), Match (processing speed and executive function), Line Orientation (visuospatial skills), and Animal Fluency (language). It is a brief, tablet-based cognitive battery validated in English and Spanish, administered by an assessor. Garre-Olmo [28] reported very good results in terms of sensitivity and specificity for the detection of MCI with the Cambridge Cognitive Examination Revised (CAM-COG-R). This is part of a bigger test and consists of 7 tasks assessing cognitive, kinesthetic, visuospatial and motor features on a touchscreen tablet. It can be obtained by purchasing the CAMDEX-DS-II (A Comprehensive Assessment for Dementia in People with Down Syndrome and Others with Intellectual Disabilities) and is available in English and Dutch. The current version is administered by a professional. Park worked on a promising application that revealed the particularities of people with cognitive impairments in their daily use of the telephone keypad [80]. One might imagine downloading this module, which would evaluate keyboard use over several hours or days, taking much of the stress out of traditional exams. Another approach is home assessment, as tested by Thompson with the Mobile Monitoring of Cognitive Change (M2C2) [81], which measures visual working memory, processing speed and episodic memory. The M2C2 is a self-administered test, performed completely remotely, and the episodic memory task demonstrated good ability to distinguish Aß PET status among study participants.

This systematic review and meta-analysis have several limitations. First, it is likely to be affected by publication bias, as studies with null or negative results may be underrepresented. In addition, patient selection in the included studies limits generalizability. Indeed, many of the studies recruited highly selected or convenience samples, which may inflate performance estimates. The predominance of case–control study designs also introduces selection biases that could overestimate diagnostic accuracy compared to prospective cohort study designs. In order to limit potential bias, we excluded 13 articles that we rated, on an ad hoc basis, as having a high risk of bias according to the QUADAS-2 scale, which may also be considered a limitation of our meta-analysis. We also encountered some difficulties with the term “touchscreen device”, which is broad and unclear, as pointed out in Nurgalieva’s review about touchscreen devices. Indeed, devices are not often described in detail, and technology has undergone rapid development in recent years [82]. To address this challenge, we include several terms in our search equation intended to obtain a broad selection of articles and render our screening sensitive (see Table A1 in Appendix A). Nurgalieva’s review also highlights the heterogeneity of older people, and the need to categorize them according to the sensory or cognitive limitations they encounter, in order to be able to propose adapted tools.

5. Conclusions

Touchscreen devices can be used to detect mNCD, but their development has yet to be validated by real-life studies. Further efforts are warranted to harmonize assessment methods, although initial results are promising.

In future works, there should be methods for standardizing test procedures so that tools can be compared more easily. It would be of interest for clinical studies to describe their methods accurately and in detail, as well as the manner in which the formal diagnosis was made, in order to fully understand what is being evaluated. Results relating to tool performance are important for the purposes of comparison and should be published in all articles. Touchscreen-based tools need to be evaluated in real-life conditions with people being diagnosed with cognitive disorders, and the results compared.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/diagnostics15182383/s1. Reference [83] is cited in the supplementary materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.B., S.P. and N.U.D.; methodology, J.B., N.U.D., C.L.-L. and F.M.; validation, J.B.; formal analysis, J.B., C.L.-L. and N.U.D.; investigation, N.U.D., F.M. and B.O.; data curation, N.U.D. and F.M.; writing—original draft preparation, N.U.D. and B.O.; writing—review and editing, J.B.; supervision, J.B. and S.P.; project administration, F.B. and J.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Stéphanie Lamy, at Université Sorbonne Paris Nord for her support on the article search and Fiona Ecarnot (Université Marie & Louis Pasteur, Besançon, France) for proofreading the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MCI | Mild Cognitive Impairment |

| NCD | Neuro Cognitive Disorder |

| NINCDS-ADRDA | National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke/Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association |

| NIAAA | National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association |

| MoCA | Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| MMSE | Mini Mental State Examination |

Appendix A

Table A1.

MeSH terms used for the database query.

Table A1.

MeSH terms used for the database query.

| Themes | MeSH Terms |

|---|---|

| Age factor | elderly, elder, aged, older adult, geriatrics |

| Screening/diagnostic | Diagnosis, diagnose, screening, assessment, evaluation, testing, detection |

| Neurocognitive condition | neurodegenerative diseases, cognitive disorders, neurocognitive disorders, dementia, Alzheimer disease |

| Touchscreen device | handheld computer, numeric tablet, smartphone, mobile applications, cell phone, touch screen, computer device, mobile technology, computer, electronic device, tablet, tablet computer, mobile device, web app |

Table A2.

Characteristics of studies using a tactile tablet or smartphone.

Table A2.

Characteristics of studies using a tactile tablet or smartphone.

| Author Year, Country | Participants n (age ± SD) | Name of the Touchscreen Test Language | Functions Assessed | Self-Administration | Touchscreen Test Duration | Mobility | Reference Diagnostic Criteria | Neuropsychological Testing for Reference Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alegret 2020 [29], Spain | 61 MCI (67.74 ± 7.93) 154 control (67.98 ± 7.92) | FACEmemory® Spanish | Memory, recognition | yes | 30 | yes | NINCDS/ADRDA | NS |

| An 2024 [76], Korea | 126 MCI (70.2 ± 7.8) 55 SCD (69.7 ± 7.2) | Seoul Digital Cognitive Test Korean | Memory, attention, language, visuospatial | NS | 30 | yes | Petersen | SNSB-II |

| Berron 2024 [84], Germany and USA | 25 MCI (69.2 ± 6.8) 78 control (68.2 ± 5.5) | Remote Digital Memory Composite English and German | Memory, discrimination, Recognition | yes | NS | yes | NINCDS/ADRDA | MMSE, CERAD and neuropsychological battery tests |

| Boz 2019 [31], Turkey | 37 MCI (70.4 ± 7.3) 52 control (67.6 ± 6.0) | Virtual Supermarket Turkish | Visual and verbal memory, executive function, attention, spatial navigation | no | 25 | yes | Petersen | MMSE and neuropsychological battery tests |

| Cheah 2022 [34], Taïwan | 59 MCI (67.5 ± 6.3) 59 control (62.6 ± 5.9) | Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Taiwanese | Visuospatial, memory, organization skills, attention, visuomotor coordination | no | NS | yes | Jak et al. | Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure (paper) |

| Chin 2020 [35], Korea | 42 MCI (71.7 ± 7.3) 26 control (68.5 ± 6.3) | Inbrain Cognitive Screening Test Korean | Attention, language, visuospatial, memory and executive function | yes | 30 | yes | Petersen | MMSE and Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery |

| Freedman 2018 [37], Canada | 50 MCI 57 control | Toronto Cognitive Assessment English | Memory, orientation, visuospatial, attention, executive control, language | no | 34 | yes | NIA-AA | Neuropsychological battery tests |

| Garre-Olmo 2017 [28], Spain | 12 MCI (63.5 ± 6.5) 17 control (70.2 ± 7.4) | 7 tasks Spanish | Cognitive, kinesthetic, visuospatial, motor features | no | 10–15 | yes | Petersen | Cambridge Cognitive Examination Revised |

| Gielis 2021 [39], Belgium | 23 MCI (80.0 ± 5.2) 23 control (70.0 ± 5.4) | Klondike Solitaire Dutch | Cognitive skills, spatial and temporal function | yes | 79 | yes | Petersen | MoCA, MMSE and CDR |

| Ishikawa 2019 [27], Japan | 25 MCI (75.9 ± 5.3) 36 control (70.0 ± 5.0) | Five drawing tasks Japanese | Memory, visuospatial, executive function | no | NS | yes | Petersen | MMSE |

| Kobayashi 2022 [43], Japan | 65 MCI (74.5 ± 4.9) 52 control (72.6 ± 3.8) | Five drawing tasks Japanese | Memory, visuospatial, executive function | yes | NS | yes | NIA-AA | MMSE and neuropsychological battery tests |

| Kubota 2017 [20], USA | 4 MCI 6 control | Virtual Kitchen Challenge English | Executive function, memory, attention, processing speed | yes | NS | yes | NS | Neuropsychological battery tests |

| Li 2025 [77], China | 93 MCI (73.1 ± 4.8) 88 control (72.2 ± 5.1) | BrainNursing Chinese | Memory, language, attention, visuospatial, executive and fine motor functions | yes | 25 | yes | NS | MoCA, MMSE and a neuropsychological battery test |

| Li 2024 [74], China | 108 MCI (71.3 ± 4.5) 99 control (70.1 ± 4.0) | Drawing and Dragging Tasks Chinese | Memory, attention, orientation, visuospatial, hand motor performance | yes | 15 | yes | NINDS-ADRDA | MoCA, MMSE and a neuropsychological battery test |

| Li 2023 [44], China | 61 MCI (71.0 ± 5.8) 59 control (67.9 ± 6.2) | Digital cognitive tests + data from a smartwatch Chinese | Verbal fluency, memory, attention, listening, visuospatial and executive function | yes | NS | yes | Petersen | MMSE and MoCA |

| Li 2023 [45], China | 30 MCI (69.2 ± 5.9) 30 control (66.1 ± 7.9) | Fingertip interaction handwriting digital evaluation Chinese | Memory, orientation, optimal decision-making, fingertip executive dynamic abilities | no | NS | yes | NIA-AA | MMSE |

| Li 2022 [26], China | 43 MCI (61.9 ± 9.6) 12 control (58.3 ± 14.6) | Tree drawing test Chinese | Feature extraction of the drawing | yes | NS | yes | NS | MMSE |

| Libon 2025 [19], USA | 17 MCI (74.8 ± 7.1) 23 control (70.0 ± 8.7) | Digital neuropsychological protocol English | Memory, executive function, language | yes | 10 | yes | NS | Neuropsychological battery tests |

| Müller 2019 [47], Germany | 138 MCI (70.8 ± 8.4) 137 control (69.6 ± 7.8) | Digital Clock Drawing Test German | Visual perception and encoding, attention, anticipatory thinking, motor planning and executive functions | NS | 4 | yes | Petersen | CERAD |

| Müller 2017 [48], Germany | 30 MCI (65.3 ± 6.6) 20 control (66.9 ± 9.4) | Digitizing visuospatial construction task German | Visuospatial construction, movements kinematics, fine motor control, coordination | yes | <1 | yes | Petersen and NIA-AA | CERAD (German) |

| Na 2023 [49], Korea | 93 MCI 73 control | Inbrain Cognitive Screening Test Korean | Visuospatial skills, attention, memory, language, orientation, executive function | yes | NS | yes | Petersen | CERAD (Korean) |

| Rigby 2024 [78], USA | 62 MCI (72.1 ± 6.8) 96 control (69.0 ± 6.4) | NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery English and Spanish | Memory, executive function, processing speed | no | 30 | yes | NACC | National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center Unified Data set version 3 |

| Robens 2019 [53], Germany | 64 MCI (67.9 ± 11.2) 67 control (65.9 ± 10.3) | Digitized Tree Drawing Test German | Visuospatial and planning abilities, semantic memory and mental imaging | yes | 4 | yes | Petersen and McKhan | CERAD (German) and Clock Drawing test |

| Rodríguez-Salgado 2021 [54], Cuba | 46 MCI (72.7 ± 7.5) 53 control (70.4 ± 5.9) | Brain Health Assessment Cuban-Spanish | Memory, processing speed, executive function, visuospatial skills, language | yes | 10 | yes | NS | MoCA, CERAD, BHA and neuropsychological battery tests |

| Simfukwe 2022 [22], Korea | 22 MCI (67.2 ± 6.0) 22 control (53.0 ± 1.5) | Digital Trail Making Test-Black and White English and Korean | Attention, mental flexibility, visual scanning | yes | 5 | yes | NS | Trail Making Test-Black and White |

| Sloane 2022 [58], USA | 21 MCI (71.1) 65 control (70.2) | Miro Health English | Movements, speech, language | yes | 5 to 60 | yes | American Academy of Neurology | MMSE, Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status; Geriatric Depression Scale |

| Suzumura 2018 [59], Japan | 15 MCI (74.3 ± 6.0) 48 control (73.6 ± 8.3) | JustTouch screen Japanese | Finger motor skills | yes | NS | yes | Petersen | MMSE |

| Um Din 2024 [72], France | 49 mNCD (79.5 ± 6.0) 47 control (78.2 ± 8.5) | Digital Clock Drawing Test French | Visuospatial, memory, planification | no | 5 | yes | DSM-V | Neuropsychological battery tests and paper CDT |

| Wu 2023 [63], China | 73 MCI 175 control | Efficient Online MCI Screening System Chinese | Memory, attention, flexibility, visuospatial and executive function, cognitive proceeding speed | yes | 10 | yes | Petersen and American Academy of Neurology | MoCA-C, IADL, AD8 questionnaire |

| Yamada 2022 [65], Japan | 67 MCI (74.1 ± 4.5) 46 control (72.3 ± 3.9) | Five drawing tasks Japanese | Visuospatial, planification | yes | NS | yes | McKhann, McKeith and Petersen | MMSE |

| Ye 2022 [66], USA | 22 MCI (73.5 ± 5.9) 35 control (67.8 ± 9.6) | BrainCheck battery V4.0.0 English | Memory, inhibition, attention, flexibility | yes | 15 to 37 | yes | Alzheimer’s Disease International | Neuropsychological battery tests |

| Yu 2019 [71], Taiwan | 14 MCI (74.9 ± 5.2) 18 control (75.8 ± 5.8) | Graphomotor tasks: two graphic and two handwriting tasks Chinese | Fine motor function | no | NS | yes | Petersen | CDR and neuropsychological battery tests |

| Zhang 2024 [75], China | 38 MCI (67.5 ± 7.2) 26 control (64.6 ± 7.0) | Tablet’s Geriatric Complex Figure Test Chinese | Memory, visuospatial, planning, attention, fine motor coordination | no | 23 | yes | NIA-AA | Neuropsychological battery tests |

| Zygouris 2015 [68], Greece | 34 MCI (70.3 ± 1.2) 21 control (66.6 ± 1.2) | Virtual Supermarket Test Greek | Memory, executive function, attention, spatial navigation | no | 10 | yes | Petersen | MoCA and MMSE |

| Zygouris 2020 [69], Greece | 47 MCI (67.9 ± 0.8) 48 SCD (66.0 ± 0.6) | Virtual Supermarket Test Greek | Visual and verbal memory, executive function, attention, spatial navigation | yes | 30 | yes | Petersen | MMSE, MoCA |

NS: not specified; SCD: Subjective Cognitive Decline. NIA-AA: National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association; NINCDS-ADRDA: National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke/Alzheimer’s disease and related Disorders Association; NACC: National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center; MoCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment; CERAD: Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease neuropsychological test battery; CDT: Clock Drawing Test; SNSB: Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery.

Table A3.

Characteristics of the studies using a computer touchscreen.

Table A3.

Characteristics of the studies using a computer touchscreen.

| Author Year, Country | Participants n (age ± SD) | Name of the Touchscreen Test Language | Functions Assessed | Self-Administration | Touchscreen Test Duration | Mobility | Reference Diagnostic Criteria | Neuropsychological Testing for Reference Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmed 2012 [23], England | 15 MCI (80.9 ± 7.2) 20 control (77.4 ± 4.0) | Computer-Administered Neuropsychological Screen for Mild Cognitive Impairment English | Memory, language, executive functions | yes | 30 | no | Petersen | ACE-R, MoCA |

| Cabinio 2020 [32], Italy | 32 MCI (76.7 ± 5.3) 107 control (76.5 ± 3.0) | The Smart Aging Serious Game Italian | Executive function, attention, memory and orientation | yes | NS | NS | NIA-AA, DSM-5 | MoCA, FCSRT, TMT A&B |

| Curiel 2016 [36], USA | 34 MCI (77.6 ± 6.3) 64 control (74.0 ± 7.3) | The Smart Aging Serious Game English | Memory, categorization | NS | 10 | NS | NS | MMSE and the Loewenstein-Acevedo Scales for Semantic Interference and Learning |

| Fukui 2015 [38], Japan | 41 MCI (75.3 ± 6.5) 75 control (75.1 ± 6.1) | Touch-panel screening test: flipping cards, finding mistakes, arranging pictures and beating evils Japanese | Memory, attention and discrimination, memory, judgment | NS | NS | no | ADNI | MMSE, HDS-R |

| Inoue 2005 [18], Japan | 22 MCI (72.0 ± 9.6) 55 control (72.6 ± 7.3) | Six tests: age and year of birth, 3 words memory test, time orientation test, 2 modified delayed-recall test, visual working memory test Japanese | Memory, orientation, visual working memory | yes | 5 | no | Petersen | Neuropsychological tests, neuroimaging examination and medical checks |

| Isernia 2021 [41], Italy | 60 MCI (74.2 ± 5.0) 74 control (75.5 ± 2.7) | Smart Aging Serious Game: 5 tasks of functional activities of everyday life Italian | Memory, spatial orientation, executive functions, attention | yes | 30 | NS | NINCDS-ADRDA | MoCA and neuropsychological battery |

| Liu 2023 [73], China | 74 MCI (66.3 ± 10.1) | Computerized cognitive training Chinese | Memory, attention, perception, executive function | NS | NS | NS | Petersen | MoCA, MMSE, CDR |

| Memória 2014 [46], Brasil | 35 MCI (73.8 ± 5.5) 41 control (71.7 ± 4.6) | Computer-Administered Neuropsychological Screen for Mild Cognitive Impairment Portuguese | Executive function, language, memory | yes | 30–50 | NS | Petersen | MoCA |

| Noguchi-Shinohara 2020 [50], Japan | 94 MCI (75.8 ± 4.1) 100 control (75.0 ± 3.2) | Computerized assessment battery for Cognition Japanese | Time orientation, recognition, memory | yes | 5 | no | International Working Group | MMSE |

| Park 2018 [51], Korea | 74 MCI (74.4 ± 6.5) 103 control (74.9 ± 7.0) | Mobile cognitive function test system for screening mild cognitive impairment English and Korean | Orientation, memory, attention, visuospatial ability, language, executive function, reaction time | no | 10 | yes | Petersen | MoCA-K |

| Porrselvi 2022 [25], India | 18 MCI (71.0 ± 5.4) 100 control (66.3 ± 7.8) | Tamil computer-assisted cognitive test Battery Tamil | Attention, memory, language, visuospatial skills and spatial cognition, executive function, processing speed | NS | 150 | yes | Petersen | MoCA, CDR Scale, MMSE, and neuropsychological battery |

| Saxton 2009 [21], USA | 228 MCI (75.2 ± 6.8) 296 control (71.8 ± 5.9) | Computer Assessment of Mild Cognitive Impairment English | Memory verbal and visual, attention, psychomotor speed, language, spatial and executive functioning | yes | 20 | yes | Criteria of the University of Pittsburgh Alzheimer Disease Research (ADRC) | MMSE and neuropsychological battery |

| Wang 2023 [24], China | 46 MCI (70.0) 46 control (68.0) | Smart 2-Min Mobile Alerting Method Chinese | Fingertip interaction, spatial navigation, executive process | no | 2 | yes | NIA-AA | MMSE |

| Wong 2017 [62], China | 59 MCI (78.2 ± 8.1) 101 control (70.5 ± 8.6) | Computerized Cognitive Screen English | Memory, executive functions, orientation, attention and working memory | yes | 15 | no | NS | MoCA |

| Wu 2017 [64], France | 129 MCI (76.5 ± 7.5) 112 control (74.7 ± 6.9) | Tablet-based cancelation test French | Attention, visuospatial, psychomotor speed, fine motor coordination | yes | 3 | yes | Petersen | K-T cancelation test |

NS: not specified. NIA-AA: National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association; NINCDS-ADRDA: National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke/Alzheimer’s disease and related Disorders Association; ADNI: Alzheimer’s Disease in neuroimaging initiative; CDR: Clinical Dementia Rating Scale.

Figure A1.

Analysis of sensitivity of studies using Petersen’s MCI criteria with others [18,21,23,27,28,29,31,32,34,35,37,38,41,43,46,47,48,50,51,53,63,64,65,66,68,69,72,74,75,76].

Table A4.

Results of the quality assessment of the articles by the QUADAS-2.

Table A4.

Results of the quality assessment of the articles by the QUADAS-2.

| Study | Risk of Bias | Applicability Concerns | Decision | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Selection | Index Test | Reference Standard | Flow and Timing | Patient Selection | Index Test | Reference Standard | ||

| Ahmed 2012 [23] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Alegret 2020 [29] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| An 2024 [76] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Bergeron 2020 [30] |  | ? |  |  |  |  |  | excluded |

| Boz 2020 [31] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Cabinio 2020 [32] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Cerino 2021 [33] | ? | ? |  | ? |  |  |  | excluded |

| Cheah 2022 [34] | ? |  | ? |  | ? |  |  | included |

| Chin 2020 [35] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Curiel 2016 [36] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Freedman 2018 [37] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Fukui 2015 [38] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Garre-Olmo 2017 [28] |  |  |  | ? |  |  |  | included |

| Gielis 2021 [39] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Groppell 2019 [40] | ? |  |  |  | ? |  |  | excluded |

| Inoue 2005 [18] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Isernia 2021 [41] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Ishikawa 2019 [27] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Ishiwata 2014 [42] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | excluded |

| Kobayashi 2022 [43] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Kubota 2017 [20] | ? |  | NA |  |  |  | NA | included |

| Li 2024 [74] | ? |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Li 2025 [77] | ? |  |  |  |  |  | ? | included |

| Li 2023 [44] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Li 2022 [26] |  |  | ? |  |  |  |  | included |

| Li 2023 [45] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Libon 2024 [19] |  |  |  |  |  |  | ? | included |

| Liu 2023 [73] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Memória 2014 [46] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Morisson 2016 [70] | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | excluded |

| Müller 2019 [47] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Müller 2017 [48] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Mychajliw 2024 [79] |  |  | ? | ? | ? |  | ? | excluded |

| Na 2023 [49] | ? |  |  |  | ? |  |  | included |

| Noguchi-Shinohara 2020 [50] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Park 2018 [51] |  |  |  | ? |  |  |  | included |

| Porrselvi 2022 [25] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Possin 2018 [52] | ? | ? |  | ? |  |  |  | excluded |

| Rigby 2024 [78] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Robens 2019 [53] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Rodríguez-Salgado 2021 [54] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Satler 2015 [55] | ? |  |  | ? |  |  | ? | excluded |

| Saxton 2009 [21] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Scharre 2017 [56] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | excluded |

| Shigemori 2015 [57] |  |  | ? | ? |  |  | ? | excluded |

| Simfukwe 2022 [22] |  |  | ? |  |  |  |  | included |

| Sloane 2022 [58] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Suzumura 2018 [59] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Tamura 2006 [60] | ? |  | ? | ? |  |  |  | excluded |

| Um Din 2024 [72] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Wang 2023 [24] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Wilks 2021 [61] | ? |  |  | ? |  | ? | ? | excluded |

| Wong 2017 [62] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Wu 2023 [63] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Wu 2017 [64] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Yamada 2022 [65] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Ye 2022 [66] |  |  | ? |  |  |  |  | included |

| Yu 2019 [71] |  | ? |  |  |  | ? |  | included |

| Zhao 2019 [67] | ? | ? | ? | ? |  |  |  | excluded |

| Zhang 2024 [75] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Zygouris 2015 [68] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

| Zygouris 2020 [69] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | included |

Low Risk;

Low Risk;  High Risk; ? Unclear Risk.

High Risk; ? Unclear Risk.

Figure A2.

Analysis of sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of mild cognitive disorders by test duration [18,21,23,28,29,31,35,36,37,41,46,48,50,51,53,54,62,63,64,66,68,69,72,74,75,76].

Figure A3.

Analysis of sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of mild cognitive disorders by modality of assessment [18,21,23,26,27,28,29,31,32,34,35,37,41,43,46,47,48,50,51,53,54,62,63,64,65,66,68,69,72,74,75,76].

Figure A4.

Analysis of sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of mild cognitive disorders by type of mobile device [18,21,23,26,27,28,29,31,34,35,37,38,43,47,48,50,51,53,54,62,63,64,65,66,68,69,72,74,75,76].

Figure A5.

Analysis of sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of mild cognitive disorders by type of touchscreen device [18,21,23,26,27,28,29,31,32,34,35,36,37,38,41,43,46,47,48,50,51,53,54,62,63,64,65,66,68,69,72,74,75,76].

References

- Dubois, B.; Padovani, A.; Scheltens, P.; Rossi, A.; Dell’Agnello, G. Timely Diagnosis for Alzheimer’s Disease: A Literature Review on Benefits and Challenges. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2016, 49, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porsteinsson, A.P.; Isaacson, R.S.; Knox, S.; Sabbagh, M.N.; Rubino, I. Diagnosis of Early Alzheimer’s Disease: Clinical Practice in 2021. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2021, 8, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokin, G.B.; Krell-Roesch, J.; Petersen, R.C.; Geda, Y.E. Mild Neurocognitive Disorder: An Old Wine in a New Bottle. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2015, 23, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jongsiriyanyong, S.; Limpawattana, P. Mild Cognitive Impairment in Clinical Practice: A Review Article. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen. 2018, 33, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanford, A.M. Mild Cognitive Impairment. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2017, 33, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, E.; Willoughby, T.; Rushing, A.; Bechtel, L.; Gilbert, J. Use of Computer Input Devices by Older Adults. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2005, 24, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs-Ericsson, N.; Blazer, D.G. The New DSM-5 Diagnosis of Mild Neurocognitive Disorder and Its Relation to Research in Mild Cognitive Impairment. Aging Ment. Health 2015, 19, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-mental state”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, T.C.C.; Machado, L.; Bulgacov, T.M.; Rodrigues-Júnior, A.L.; Costa, M.L.G.; Ximenes, R.C.C.; Sougey, E.B. Is the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) Screening Superior to the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) in the Detection of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) in the Elderly? Int Psychogeriatr 2019, 31, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, C.T.; Seward, K.; Patterson, A.; Melton, A.; MacDonald-Wicks, L. Evaluation of Available Cognitive Tools Used to Measure Mild Cognitive Decline: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breton, A.; Casey, D.; Arnaoutoglou, N.A. Cognitive Tests for the Detection of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), the Prodromal Stage of Dementia: Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2019, 34, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaquinto, F.; Battista, P.; Angelelli, P. Touchscreen Cognitive Tools for Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia Used in Primary Care Across Diverse Cultural and Literacy Populations: A Systematic Review. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2022, 90, 1359–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Um Din, N.; Maronnat, F.; Zolnowski-Kolp, V.; Otmane, S.; Belmin, J. Diagnosis Accuracy of Touchscreen-Based Testings for Major Neurocognitive Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Age Ageing 2025, 54, afaf204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salameh, J.-P.; Bossuyt, P.M.; McGrath, T.A.; Thombs, B.D.; Hyde, C.J.; Macaskill, P.; Deeks, J.J.; Leeflang, M.; Korevaar, D.A.; Whiting, P.; et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies (PRISMA-DTA): Explanation, Elaboration, and Checklist. BMJ 2020, 370, m2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiting, P.F.; Rutjes, A.W.S.; Westwood, M.E.; Mallett, S.; Deeks, J.J.; Reitsma, J.B.; Leeflang, M.M.G.; Sterne, J.A.C.; Bossuyt, P.M.M. QUADAS-2 Group QUADAS-2: A Revised Tool for the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyaga, V.N.; Arbyn, M. Metadta: A Stata Command for Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Data—A Tutorial. Arch. Public Health 2022, 80, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, M.; Urakami, K.; Taniguchi, M.; Kimura, Y.; Saito, J.; Nakashima, K. Evaluation of a Computerized Test System to Screen for Mild Cognitive Impairment. Psychogeriatrics 2005, 5, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libon, D.J.; Swenson, R.; Price, C.C.; Lamar, M.; Cosentino, S.; Bezdicek, O.; Kling, M.A.; Tobyne, S.; Jannati, A.; Banks, R.; et al. Digital Assessment of Cognition in Neurodegenerative Disease: A Data Driven Approach Leveraging Artificial Intelligence. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1415629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; Maeta, T.; Okada, Y.; Miura, Y.; Martono, N.P.; Ohwada, H.; Tania, G. Feature Extraction Based on Touch Interaction Data in Virtual Reality-Based IADL for Characterization of Mild Cognitive Impairment. In Proceedings of the 12th International Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications, Porto, Portugal, 27 February–1 March 2017; pp. 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxton, J.; Morrow, L.; Eschman, A.; Archer, G.; Luther, J.; Zuccolotto, A. Computer Assessment of Mild Cognitive Impairment. Postgrad. Med. 2009, 121, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simfukwe, C.; Youn, Y.C.; Kim, S.Y.; An, S.S. Digital Trail Making Test-Black and White: Normal vs MCI. Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult 2022, 29, 1296–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; de Jager, C.; Wilcock, G. A Comparison of Screening Tools for the Assessment of Mild Cognitive Impairment: Preliminary Findings. Neurocase 2012, 18, 336–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, T.; Wang, C.; Ogihara, A.; Ma, X.; Huang, S.; Zhou, S.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; Li, K. A New Smart 2-Min Mobile Alerting Method for Mild Cognitive Impairment Due to Alzheimer’s Disease in the Community. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porrselvi, A.P. TAM Battery: Development and Pilot Testing of a Tamil Computer-Assisted Cognitive Test Battery for Older Adults. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2023, 37, 1005–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, J.; Yang, J.; Yang, H.; Lan, M.; Gao, L. Characterizing Cognitive Impairment through Drawing Features Extracted from the Tree Drawing Test. In Proceedings of the 2022 7th International Conference on Intelligent Informatics and Biomedical Science (ICIIBMS), Nara, Japan, 24–26 November 2022; Volume 7, pp. 341–347. [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, T.; Nemoto, M.; Nemoto, K.; Takeuchi, T.; Numata, Y.; Watanabe, R.; Tsukada, E.; Ota, M.; Higashi, S.; Arai, T.; et al. Handwriting Features of Multiple Drawing Tests for Early Detection of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Preliminary Result. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2019, 264, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garre-Olmo, J.; Faúndez-Zanuy, M.; López-de-Ipiña, K.; Calvó-Perxas, L.; Turró-Garriga, O. Kinematic and Pressure Features of Handwriting and Drawing: Preliminary Results Between Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment, Alzheimer Disease and Healthy Controls. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2017, 14, 960–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegret, M.; Muñoz, N.; Roberto, N.; Rentz, D.M.; Valero, S.; Gil, S.; Marquié, M.; Hernández, I.; Riveros, C.; Sanabria, A.; et al. A Computerized Version of the Short Form of the Face-Name Associative Memory Exam (FACEmemory®) for the Early Detection of Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2020, 12, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, M.F.; Landset, S.; Zhou, X.; Ding, T.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M.; Zhao, F.; Du, B.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Zhong, L.; et al. Utility of MemTrax and Machine Learning Modeling in Classification of Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2020, 77, 1545–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eraslan Boz, H.; Limoncu, H.; Zygouris, S.; Tsolaki, M.; Giakoumis, D.; Votis, K.; Tzovaras, D.; Öztürk, V.; Yener, G.G. A New Tool to Assess Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment in Turkish Older Adults: Virtual Supermarket (VSM). Neuropsychol. Dev. Cogn. B Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 2020, 27, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabinio, M.; Rossetto, F.; Isernia, S.; Saibene, F.L.; Di Cesare, M.; Borgnis, F.; Pazzi, S.; Migliazza, T.; Alberoni, M.; Blasi, V.; et al. The Use of a Virtual Reality Platform for the Assessment of the Memory Decline and the Hippocampal Neural Injury in Subjects with Mild Cognitive Impairment: The Validity of Smart Aging Serious Game (SASG). J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerino, E.S.; Katz, M.J.; Wang, C.; Qin, J.; Gao, Q.; Hyun, J.; Hakun, J.G.; Roque, N.A.; Derby, C.A.; Lipton, R.B.; et al. Variability in Cognitive Performance on Mobile Devices Is Sensitive to Mild Cognitive Impairment: Results from the Einstein Aging Study. Front. Digit. Health 2021, 3, 758031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, W.-T.; Hwang, J.-J.; Hong, S.-Y.; Fu, L.-C.; Chang, Y.-L.; Chen, T.-F.; Chen, I.-A.; Chou, C.-C. A Digital Screening System for Alzheimer Disease Based on a Neuropsychological Test and a Convolutional Neural Network: System Development and Validation. JMIR Med. Inform. 2022, 10, e31106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, J.; Kim, D.E.; Lee, H.; Yun, J.; Lee, B.H.; Park, J.; Yeom, J.; Shin, D.S.; Na, D.L. A Validation Study of the Inbrain CST: A Tablet Computer-Based Cognitive Screening Test for Elderly People with Cognitive Impairment. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2020, 35, e292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curiel, R.E.; Crocco, E.; Rosado, M.; Duara, R.; Greig, M.T.; Raffo, A.; Loewenstein, D.A. A Brief Computerized Paired Associate Test for the Detection of Mild Cognitive Impairment in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2016, 54, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedman, M.; Leach, L.; Carmela Tartaglia, M.; Stokes, K.A.; Goldberg, Y.; Spring, R.; Nourhaghighi, N.; Gee, T.; Strother, S.C.; Alhaj, M.O.; et al. The Toronto Cognitive Assessment (TorCA): Normative Data and Validation to Detect Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2018, 10, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukui, Y.; Yamashita, T.; Hishikawa, N.; Kurata, T.; Sato, K.; Omote, Y.; Kono, S.; Yunoki, T.; Kawahara, Y.; Hatanaka, N.; et al. Computerized Touch-Panel Screening Tests for Detecting Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease. Intern. Med. 2015, 54, 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gielis, K.; Vanden Abeele, M.-E.; Verbert, K.; Tournoy, J.; De Vos, M.; Vanden Abeele, V. Detecting Mild Cognitive Impairment via Digital Biomarkers of Cognitive Performance Found in Klondike Solitaire: A Machine-Learning Study. Digit. Biomark. 2021, 5, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groppell, S.; Soto-Ruiz, K.M.; Flores, B.; Dawkins, W.; Smith, I.; Eagleman, D.M.; Katz, Y. A Rapid, Mobile Neurocognitive Screening Test to Aid in Identifying Cognitive Impairment and Dementia (BrainCheck): Cohort Study. JMIR Aging 2019, 2, e12615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isernia, S.; Cabinio, M.; Di Tella, S.; Pazzi, S.; Vannetti, F.; Gerli, F.; Mosca, I.E.; Lombardi, G.; Macchi, C.; Sorbi, S.; et al. Diagnostic Validity of the Smart Aging Serious Game: An Innovative Tool for Digital Phenotyping of Mild Neurocognitive Disorder. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2021, 83, 1789–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiwata, A.; Kitamura, S.; Nomura, T.; Nemoto, R.; Ishii, C.; Wakamatsu, N.; Katayama, Y. Early Identification of Cognitive Impairment and Dementia: Results from Four Years of the Community Consultation Center. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2014, 59, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Yamada, Y.; Shinkawa, K.; Nemoto, M.; Nemoto, K.; Arai, T. Automated Early Detection of Alzheimer’s Disease by Capturing Impairments in Multiple Cognitive Domains with Multiple Drawing Tasks. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2022, 88, 1075–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Li, J.; Zhang, D.; Wu, W.; Zhao, J.; Qiang, Y. Synergy through Integration of Digital Cognitive Tests and Wearable Devices for Mild Cognitive Impairment Screening. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1183457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Ma, X.; Chen, T.; Xin, J.; Wang, C.; Wu, B.; Ogihara, A.; Zhou, S.; Liu, J.; Huang, S.; et al. A New Early Warning Method for Mild Cognitive Impairment Due to Alzheimer’s Disease Based on Dynamic Evaluation of the “Spatial Executive Process”. Digit. Health 2023, 9, 20552076231194938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memória, C.M.; Yassuda, M.S.; Nakano, E.Y.; Forlenza, O.V. Contributions of the Computer-Administered Neuropsychological Screen for Mild Cognitive Impairment (CANS-MCI) for the Diagnosis of MCI in Brazil. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2014, 26, 1483–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, S.; Herde, L.; Preische, O.; Zeller, A.; Heymann, P.; Robens, S.; Elbing, U.; Laske, C. Diagnostic Value of Digital Clock Drawing Test in Comparison with CERAD Neuropsychological Battery Total Score for Discrimination of Patients in the Early Course of Alzheimer’s Disease from Healthy Individuals. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, S.; Preische, O.; Heymann, P.; Elbing, U.; Laske, C. Diagnostic Value of a Tablet-Based Drawing Task for Discrimination of Patients in the Early Course of Alzheimer’s Disease from Healthy Individuals. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2017, 55, 1463–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Na, S.; Seo, S.W.; Kim, Y.J.; Yoo, H.; Lee, E.-S. Correlation Analysis between Subtest Scores of CERAD-K and a Newly Developed Tablet Computer-Based Digital Cognitive Test (Inbrain CST). Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1178324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi-Shinohara, M.; Domoto, C.; Yoshida, T.; Niwa, K.; Yuki-Nozaki, S.; Samuraki-Yokohama, M.; Sakai, K.; Hamaguchi, T.; Ono, K.; Iwasa, K.; et al. A New Computerized Assessment Battery for Cognition (C-ABC) to Detect Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia around 5 Min. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-H.; Jung, M.; Kim, J.; Park, H.Y.; Kim, J.-R.; Park, J.-H. Validity of a Novel Computerized Screening Test System for Mild Cognitive Impairment. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2018, 30, 1455–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Possin, K.; Moskowitz, T.; Erlhoff, S.; Rogers, K.; Johnson, E.; Steele, N.; Higgins, J.; Stiver, J.; Alioto, A.; Farias, S.; et al. The Brain Health Assessment for Detecting and Diagnosing Neurocognitive Disorders. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018, 66, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robens, S.; Heymann, P.; Gienger, R.; Hett, A.; Müller, S.; Laske, C.; Loy, R.; Ostermann, T.; Elbing, U. The Digital Tree Drawing Test for Screening of Early Dementia: An Explorative Study Comparing Healthy Controls, Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment, and Patients with Early Dementia of the Alzheimer Type. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2019, 68, 1561–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Salgado, A.M.; Llibre-Guerra, J.J.; Tsoy, E.; Peñalver-Guia, A.I.; Bringas, G.; Erlhoff, S.J.; Kramer, J.H.; Allen, I.E.; Valcour, V.; Miller, B.L.; et al. A Brief Digital Cognitive Assessment for Detection of Cognitive Impairment in Cuban Older Adults. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2021, 79, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satler, C.; Beham, F.; Garcias, A.; Tomaz, C.; Tavares, M. Computerized Spatial Delayed Recognition Span Task: A Specific Tool to Assess Visuospatial Working Memory. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2015, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scharre, D.W.; Chang, S.I.; Nagaraja, H.N.; Vrettos, N.E.; Bornstein, R.A. Digitally Translated Self-Administered Gerocognitive Examination (eSAGE): Relationship with Its Validated Paper Version, Neuropsychological Evaluations, and Clinical Assessments. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2017, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigemori, T.; Harbi, Z.; Kawanaka, H.; Hicks, Y.; Setchi, R.; Takase, H.; Tsuruoka, S. Feature Extraction Method for Clock Drawing Test; Ding, L., Pang, C., Kew, L., Jain, L., Howlett, R., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 60, pp. 1707–1714. [Google Scholar]

- Sloane, K.L.; Mefford, J.A.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, M.; Zhou, G.; Fabian, R.; Wright, A.E.; Glenn, S. Validation of a Mobile, Sensor-Based Neurobehavioral Assessment with Digital Signal Processing and Machine-Learning Analytics. Cogn. Behav. Neurol. 2022, 35, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzumura, S.; Osawa, A.; Maeda, N.; Sano, Y.; Kandori, A.; Mizuguchi, T.; Yin, Y.; Kondo, I. Differences among Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease, Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment and Healthy Older Adults in Finger Dexterity. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2018, 18, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, T.; Tshji, M.; Higashi, Y.; Sekine, M.; Kohdabashi, A.; Fujimoto, T.; Mitsuyama, M. New Computer-Based Cognitive Function Test for the Elderly. Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2006, 1, 692–694. [Google Scholar]

- Wilks, H.; Aschenbrenner, A.; Gordon, B.; Balota, D.; Fagan, A.; Musiek, E.; Balls-Berry, J.; Benzinger, T.; Cruchaga, C.; Morris, J.; et al. Sharper in the Morning: Cognitive Time of Day Effects Revealed with High-Frequency Smartphone Testing. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2021, 43, 825–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.; Fong, C.-H.; Mok, V.C.-T.; Leung, K.-T.; Tong, R.K.-Y. Computerized Cognitive Screen (CoCoSc): A Self-Administered Computerized Test for Screening for Cognitive Impairment in Community Social Centers. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2017, 59, 1299–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Tu, J.; Liu, Z.; Cao, L.; He, Y.; Huang, J.; Tao, J.; Wong, M.N.K.; Chen, L.; Lee, T.M.C.; et al. An Effective Test (EOmciSS) for Screening Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment in a Community Setting: Development and Validation Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e40858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-H.; Vidal, J.-S.; de Rotrou, J.; Sikkes, S.A.M.; Rigaud, A.-S.; Plichart, M. Can a Tablet-Based Cancellation Test Identify Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults? PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, Y.; Kobayashi, M.; Shinkawa, K.; Nemoto, M.; Ota, M.; Nemoto, K.; Arai, T. Automated Analysis of Drawing Process for Detecting Prodromal and Clinical Dementia. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Digital Health (ICDH), Barcelona, Spain, 11–15 July 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, S.; Sun, K.; Huynh, D.; Phi, H.Q.; Ko, B.; Huang, B.; Hosseini Ghomi, R. A Computerized Cognitive Test Battery for Detection of Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment: Instrument Validation Study. JMIR Aging 2022, 5, e36825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, K.; Yoshizumi, T.; Ota, M.; Ekoyama, S.; Arai, T. Development of Cognitive Level Estimation Model Using Mobile Applications. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2019, 15, 957–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zygouris, S.; Giakoumis, D.; Votis, K.; Doumpoulakis, S.; Ntovas, K.; Segkouli, S.; Karagiannidis, C.; Tzovaras, D.; Tsolaki, M. Can a Virtual Reality Cognitive Training Application Fulfill a Dual Role? Using the Virtual Supermarket Cognitive Training Application as a Screening Tool for Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2015, 44, 1333–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zygouris, S.; Iliadou, P.; Lazarou, E.; Giakoumis, D.; Votis, K.; Alexiadis, A.; Triantafyllidis, A.; Segkouli, S.; Tzovaras, D.; Tsiatsos, T.; et al. Detection of Mild Cognitive Impairment in an At-Risk Group of Older Adults: Can a Novel Self-Administered Serious Game-Based Screening Test Improve Diagnostic Accuracy? J. Alzheimers Dis. 2020, 78, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, R.; Pei, H.; Novak, G.; Kaufer, D.; Welsh-Bohmer, K.; Ruhmel, S.; Narayan, V.A. Validation of a Novel Computerized Selfadministered Memory-Screening Test with Automated Reporting (SAMSTAR) in Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment and Normal Control Participants: A Randomized, Crossover, Controlled Study. Neuropsychopharmacology 2016, 41, S345–S346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, N.-Y.; Chang, S.-H. Characterization of the Fine Motor Problems in Patients with Cognitive Dysfunction—A Computerized Handwriting Analysis. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2019, 65, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um Din, N.; Maronnat, F.; Pariel, S.; Badra, F.; Belmin, J. A Digital Clock Drawing Test on Tablet for the Diagnosis of Neurocognitive Disorders in Older Adults. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2024, 316, 1878–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.-Y.; Xing, Y.; Zhang, Z.-H.; Zhang, Q.-G.; Dong, M.; Wang, H.; Cai, L.; Wang, X.; Tang, Y. Validation of a Computerized Cognitive Training Tool to Assess Cognitive Impairment and Enable Differentiation Between Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2023, 96, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Li, J.; Chai, J.; Wu, W.; Chaudhary, S.; Zhao, J.; Qiang, Y. Detection of Mild Cognitive Impairment Through Hand Motor Function Under Digital Cognitive Test: Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2024, 12, e48777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lv, L.; Shen, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y. A Tablet-Based Multi-Dimensional Drawing System Can Effectively Distinguish Patients with Amnestic MCI from Healthy Individuals. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Shin, J.S.; Bae, N.; Seo, S.W.; Na, D.L. Validity of the Tablet-Based Digital Cognitive Test (SCST) in Identifying Different Degrees of Cognitive Impairment. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2024, 39, e247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Xue, C.; Wu, R.; Wu, W.; Zhao, J.; Qiang, Y. Unearthing Subtle Cognitive Variations: A Digital Screening Tool for Detecting and Monitoring Mild Cognitive Impairment. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2025, 41, 2579–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, T.; Gregoire, A.M.; Reader, J.; Kahsay, Y.; Fisher, J.; Kairys, A.; Bhaumik, A.K.; Rahman-Filipiak, A.; Maher, A.C.; Hampstead, B.M.; et al. Identification of Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment among Black and White Community-Dwelling Older Adults Using NIH Toolbox Cognition Tablet Battery. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2024, 30, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mychajliw, C.; Holz, H.; Minuth, N.; Dawidowsky, K.; Eschweiler, G.W.; Metzger, F.G.; Wortha, F. Performance Differences of a Touch-Based Serial Reaction Time Task in Healthy Older Participants and Older Participants with Cognitive Impairment on a Tablet: Experimental Study. JMIR Aging 2024, 7, e48265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.-H. Discriminant Power of Smartphone-Derived Keystroke Dynamics for Mild Cognitive Impairment Compared to a Neuropsychological Screening Test: Cross-Sectional Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e59247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, L.I.; Kunicki, Z.J.; Emrani, S.; Strenger, J.; De Vito, A.N.; Britton, K.J.; Dion, C.; Harrington, K.D.; Roque, N.; Salloway, S.; et al. Remote and In-Clinic Digital Cognitive Screening Tools Outperform the MoCA to Distinguish Cerebral Amyloid Status among Cognitively Healthy Older Adults. Alzheimers Dement. 2023, 15, e12500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurgalieva, L.; Jara Laconich, J.J.; Baez, M.; Casati, F.; Marchese, M. A Systematic Literature Review of Research-Derived Touchscreen Design Guidelines for Older Adults. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 22035–22058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, M.D.; Moher, D.; Thombs, B.D.; McGrath, T.A.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Clifford, T.; Cohen, J.F.; Deeks, J.J.; Gatsonis, C.; Hooft, L.; et al. Preferred reporting items for a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies: The PRISMA-DTA statement. JAMA 2018, 319, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berron, D.; Glanz, W.; Clark, L.; Basche, K.; Grande, X.; Güsten, J.; Billette, O.V.; Hempen, I.; Naveed, M.H.; Diersch, N.; et al. A Remote Digital Memory Composite to Detect Cognitive Impairment in Memory Clinic Samples in Unsupervised Settings Using Mobile Devices. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).