Nested Melanoma and Superficial Spreading Melanoma with Prominent Nests—A Retrospective Study on Clinical Characteristics and PRAME Expression

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Database Search and Study Cohort

2.2. Clinical Assessment

2.3. Immunohistochemical Analysis

2.4. Statistics

2.5. Ethics Statement

3. Results

3.1. Epidemiological Data

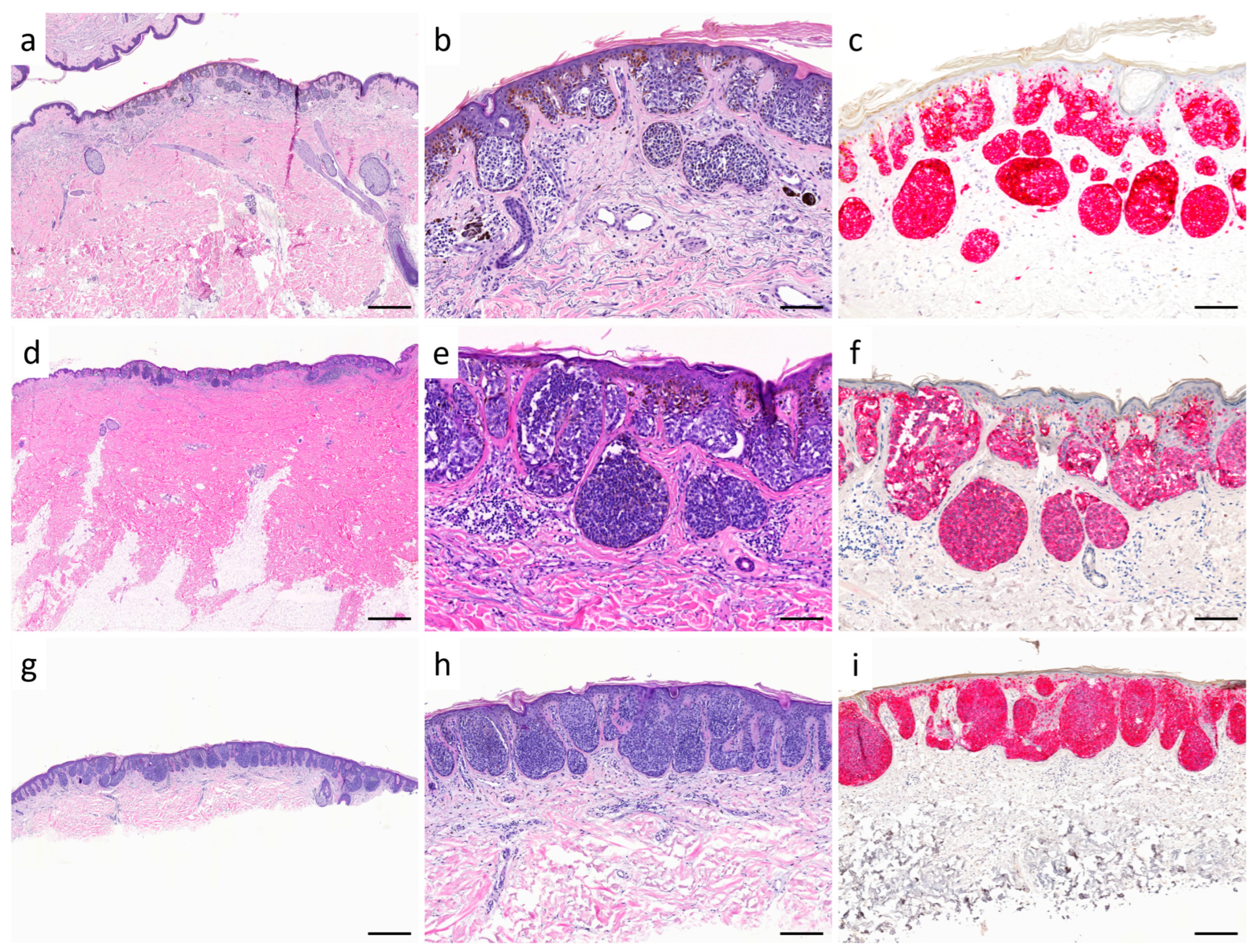

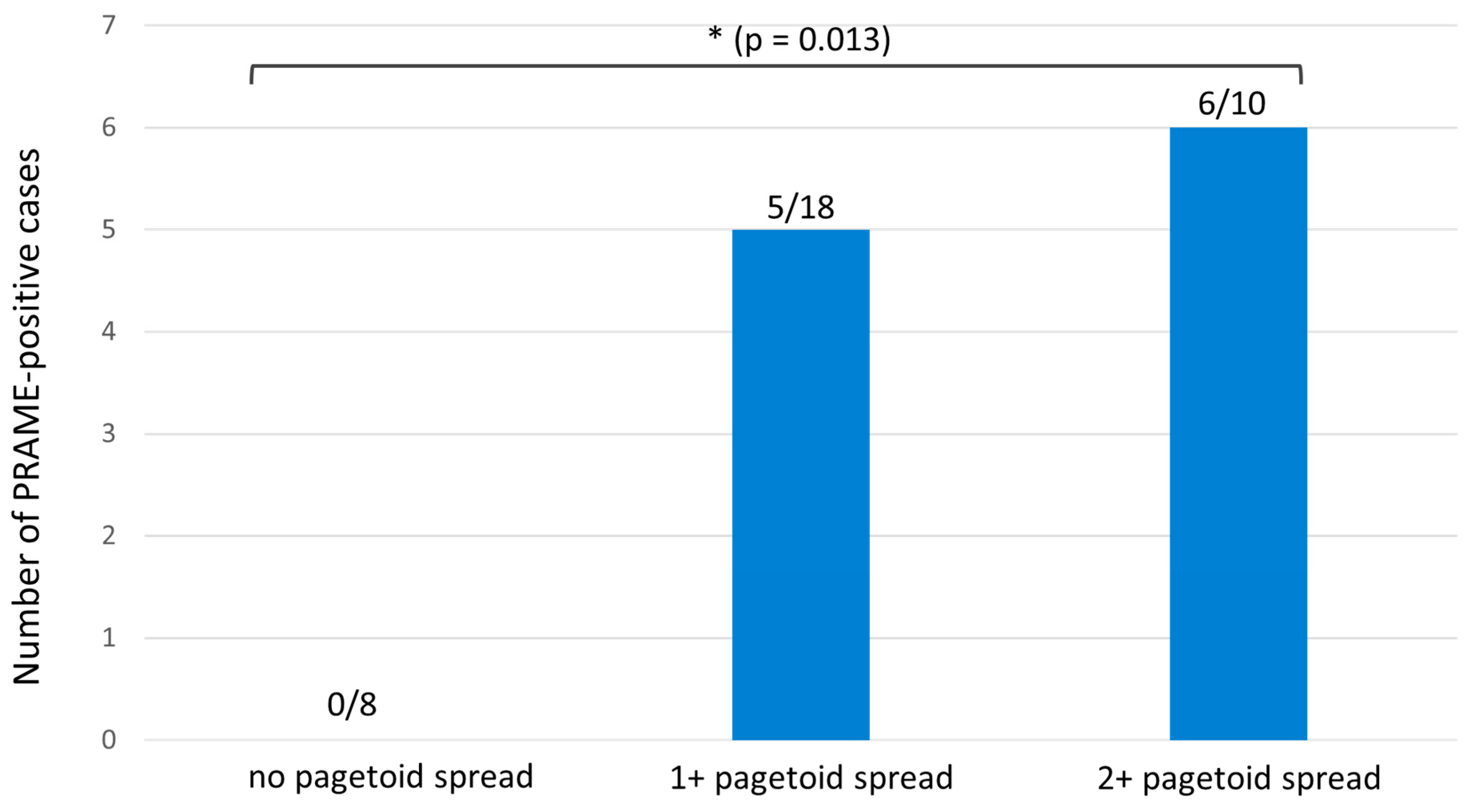

3.2. Comparison of PRAME and Melan A Immunohistochemistry in SSM with Prominent Nests, Nested Melanoma and Dysplastic Melanocytic Nevi

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

| Characteristics | Nested Melanoma | Melanocytic Nevi | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical findings | Patient history | - Progressive growth in size - Changes in color | - Typically no significant increase in size in adult patients - No changes in color |

| Age | - Older patients (mostly patients > 65 years, and rarely in younger patients) [2] This study: - Nested melanoma: mean age 60.5 years - SSM with prominent nests: mean age 77.1 years | - In older patients, new nevi should generally no longer appear and should be primarily considered suspicious | |

| Macroscopic findings | - Typical melanoma features: asymmetry of color and shape, multiple colors, irregular borders, size > 6 mm | - Symmetric, well-defined melanocytic lesion, uniform in color, size of <5 mm | |

| Dermatoscopy | - Typical common melanoma features: atypical pigment network, blue structures, signs of regression, atypical vascular patterns - Characteristics: large, irregular round to oval dots and globules [2] | - Uniform, well-defined pigment network, often round or oval structures, homogenous coloration, absence of irregular streaks or signs of regression | |

| Histopathological findings | Morphology | - Broad melanocytic lesion - Extremely well nested: melanocytes in large, rounded “cannonball” junctional nests of varying shapes and sizes - Moderate to severe cellular atypia [1] | - Melanocytic nevus: regular arrangement of melanocytes in nests or cords at dermoepidermal junction, uniform nevus cells - Dysplastic nevus: more irregular asymmetrical melanocytic nests, mild cellular atypia, bridging of melanocytes |

| Immunohistochemistry | - Usually no or mild pagetoid intraepidermal spread of melanocytes in Melan A staining - More pronounced pagetoid spread suggests transition to superficial spreading melanoma (SSM) type This study: - Nested melanoma: Diffuse PRAME expression in 19% - SSM with prominent nests: Diffuse PRAME expression in 60% | - Usually no or mild pagetoid intraepidermal spread of melanocytes in Melan A staining - Usually no diffuse PRAME expression, cases with diffuse PRAME positivity should be critically assessed [11] | |

| Genetic aberrations | - Array CGH: multiple gains and losses on several chromosomes - FISH: melanoma-typical aberrations, e.g., RREB1, MYB, and CCND1 - BRAFV600 mutation possible but not well studied [3] | - No aberrations in aCGH and FISH - Frequent BRAFV600 mutation (60–80%) [25,26] | |

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kutzner, H.; Metzler, G.; Argenyi, Z.; Requena, L.; Palmedo, G.; Mentzel, T.; Rutten, A.; Hantschke, M.; Paredes, B.E.; Scharer, L.; et al. Histological and genetic evidence for a variant of superficial spreading melanoma composed predominantly of large nests. Mod. Pathol. 2012, 25, 838–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, C.; Zalaudek, I.; Piana, S.; Pellacani, G.; Lallas, A.; Reggiani, C.; Argenziano, G. Dermoscopy and Confocal Microscopy of Nested Melanoma of the Elderly: Recognizing a Newly Defined Entity. JAMA Dermatol. 2013, 149, 941–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Pennacchia, I.; Garcovich, S.; Gasbarra, R.; Leone, A.; Arena, V.; Massi, G. Morphological and molecular characteristics of nested melanoma of the elderly (evolved lentiginous melanoma). Virchows Arch. 2012, 461, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, H.; Lethé, B.; Lehmann, F.; van Baren, N.; Baurain, J.F.; de Smet, C.; Chambost, H.; Vitale, M.; Moretta, A.; Boon, T.; et al. Characterization of an antigen that is recognized on a melanoma showing partial HLA loss by CTL expressing an NK inhibitory receptor. Immunity 1997, 6, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodison, S.; Urquidi, V. The cancer testis antigen PRAME as a biomarker for solid tumor cancer management. Biomark. Med. 2012, 6, 629–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curigliano, G.; Bagnardi, V.; Ghioni, M.; Louahed, J.; Brichard, V.; Lehmann, F.F.; Marra, A.; Trapani, D.; Criscitiello, C.; Viale, G. Expression of tumor-associated antigens in breast cancer subtypes. Breast 2020, 49, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Barger, C.J.; Eng, K.H.; Klinkebiel, D.; Link, P.A.; Omilian, A.; Bshara, W.; Odunsi, K.; Karpf, A.R. PRAME expression and promoter hypomethylation in epithelial ovarian cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 45352–45369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujol, J.L.; De Pas, T.; Rittmeyer, A.; Vallières, E.; Kubisa, B.; Levchenko, E.; Wiesemann, S.; Masters, G.A.; Shen, R.; Tjulandin, S.A.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of the PRAME Cancer Immunotherapeutic in Patients with Resected Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Phase I Dose Escalation Study. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2016, 11, 2208–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutzmer, R.; Rivoltini, L.; Levchenko, E.; Testori, A.; Utikal, J.; Ascierto, P.A.; Demidov, L.; Grob, J.J.; Ridolfi, R.; Schadendorf, D.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the PRAME cancer immunotherapeutic in metastatic melanoma: Results of a phase I dose escalation study. ESMO Open 2016, 1, e000068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lezcano, C.; Jungbluth, A.A.; Nehal, K.S.; Hollmann, T.J.; Busam, K.J. PRAME Expression in Melanocytic Tumors. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2018, 42, 1456–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gassenmaier, M.; Hahn, M.; Metzler, G.; Bauer, J.; Yazdi, A.S.; Keim, U.; Garbe, C.; Wagner, N.B.; Forchhammer, S. Diffuse PRAME Expression Is Highly Specific for Thin Melanomas in the Distinction from Severely Dysplastic Nevi but Does Not Distinguish Metastasizing from Non-Metastasizing Thin Melanomas. Cancers 2021, 13, 3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tio, D.; Willemsen, M.; Krebbers, G.; Kasiem, F.R.; Hoekzema, R.; van Doorn, R.; Bekkenk, M.W.; Luiten, R.M. Differential Expression of Cancer Testis Antigens on Lentigo Maligna and Lentigo Maligna Melanoma. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2020, 42, 625–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.; Ko, C.J.; McNiff, J.M.; Galan, A. Pitfalls of PRAME Immunohistochemistry in a Large Series of Melanocytic and Nonmelanocytic Lesions With Literature Review. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2024, 46, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Bello, G.; Pini, G.M.; Giagnacovo, M.; Patriarca, C. PRAME expression in 137 primary cutaneous melanomas and comparison with 38 related metastases. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2023, 251, 154915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbe, C.; Metzler, G. Nested melanoma, a newly defined entity. JAMA Dermatol. 2013, 149, 905–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastian, B.C.; LeBoit, P.E.; Hamm, H.; Bröcker, E.B.; Pinkel, D. Chromosomal gains and losses in primary cutaneous melanomas detected by comparative genomic hybridization. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 2170–2175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Curtin, J.A.; Fridlyand, J.; Kageshita, T.; Patel, H.N.; Busam, K.J.; Kutzner, H.; Cho, K.H.; Aiba, S.; Brocker, E.B.; LeBoit, P.E.; et al. Distinct sets of genetic alterations in melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 2135–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balch, C.M.; Soong, S.J.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Thompson, J.F.; Reintgen, D.S.; Cascinelli, N.; Urist, M.; McMasters, K.M.; Ross, M.I.; Kirkwood, J.M.; et al. Prognostic factors analysis of 17,600 melanoma patients: Validation of the American Joint Committee on Cancer melanoma staging system. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001, 19, 3622–3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncati, L.; Pusiol, T.; Piscioli, F. Thin Melanoma: A Generic Term Including Four Histological Subtypes of Cutaneous Melanoma. Acta Dermatovenerol. Croat. 2016, 24, 169–174. [Google Scholar]

- Måsbäck, A.; Olsson, H.; Westerdahl, J.; Ingvar, C.; Jonsson, N. Prognostic factors in invasive cutaneous malignant melanoma: A population-based study and review. Melanoma Res. 2001, 11, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteman, D.C.; Baade, P.D.; Olsen, C.M. More people die from thin melanomas (≤1 mm) than from thick melanomas (>4 mm) in Queensland, Australia. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2015, 135, 1190–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forchhammer, S.; Aebischer, V.; Lenders, D.; Seitz, C.M.; Schroeder, C.; Liebmann, A.; Abele, M.; Wild, H.; Bien, E.; Krawczyk, M.; et al. Characterization of PRAME immunohistochemistry reveals lower expression in pediatric melanoma compared to adult melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2024, 37, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasini, C.F.; Michelerio, A.; Isoletta, E.; Barruscotti, S.; Wade, B.; Muzzi, A. A Clinico-Pathological Multidisciplinary Team Increases the Efficacy of Skin Biopsy and Reduces Clinical Risk in Dermatology. Dermatopathology 2023, 10, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolcato, V.; Michelerio, A. Dermoscopy for Cutaneous Melanoma: Under the Eye of Both the Dermatologist and the Legal Doctor. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2022, 12, e2022100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, P.M.; Harper, U.L.; Hansen, K.S.; Yudt, L.M.; Stark, M.; Robbins, C.M.; Moses, T.Y.; Hostetter, G.; Wagner, U.; Kakareka, J.; et al. High frequency of BRAF mutations in nevi. Nat. Genet. 2003, 33, 19–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, R.Q.; He, L.; Zheng, S.; Hong, Y.; Ma, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, L.; Guo, X.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.Y.; et al. BRAF exon 15 T1799A mutation is common in melanocytic nevi, but less prevalent in cutaneous malignant melanoma, in Chinese Han. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2011, 131, 1129–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | SSM with Prominent Nests | Nested Melanoma |

|---|---|---|

| Total, n | 10 | 26 |

| Age, years, mean, (SD; range) | 77.1 (10.6, 59–86) | 60.5 (12.7, 41–84) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 3 (30) | 20 (77) |

| Female | 7 (70) | 6 (23) |

| Localization of primary tumor, n (%) | ||

| Trunk | 6 (60) | 20 (77) |

| Head/neck | 0 (0) | 1 (4) |

| Upper extremities | 1 (10) | 3 (11) |

| Lower extremities | 3 (30) | 2 (8) |

| Ulceration, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| No | 10 (100) | 26 (100) |

| Regression, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 1 (10) | 1 (4) |

| No | 10 (90) | 24 (96) |

| Nevus association, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 2 (20) | 4 (15) |

| No | 8 (80) | 22 (85) |

| Clark Level, n (%) | ||

| I | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| II | 4 (40) | 13 (50) |

| III | 5 (50) | 9 (35) |

| IV | 1 (10) | 4 (15) |

| V | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Breslow tumor thickness, mm, median (range) | 0.56 (0.3–0.72) | 0.4 (0.25–1.2) |

| Breslow tumor thickness/T stage (TNM classification, AJCC 2017), number of patients (%) | ||

| ≤1.0 mm/T1 | 10 (100) | 25 (96) |

| >1.0–2.0 mm/T2 | 0 (0) | 1 (4) |

| >2.0–4.0 mm/T3 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| >4.0 mm/T4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Melanoma stage (8th edition, AJCC 2017) | ||

| Ia, n (%) | 10 (100) | 25 (96) |

| Ib, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) |

| II, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| III, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| IV, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Patients with follow-up data, n | 1 | 18 |

| Duration of follow-up, years, mean (SD; range) | 1 (0; 1) | 4.9 (3.2; 0–12) |

| Recurrences, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Metastases, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Multiple melanomas, n (%) | 2 (20) | 4 (15) |

| SSM with Prominent Nests and Nested Melanoma | Dysplastic Melanocytic Nevi | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient No./Sex | Age (y) | PRAME Junctional | PRAME Dermal | Diffuse PRAME | Pagetoid Spread | Patient No./Sex | Age (y) | PRAME Junctional | PRAME Dermal | Diffuse PRAME | Pagetoid Spread |

| 1/M | 49 | 0 | 0 | − | 1+ | 37/M | 44 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 |

| 2/M | 76 | 1+ | 0 | − | 0 | 38/M | 71 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 |

| 3/M | 70 | 1+ | 0 | − | 1+ | 39/M | 51 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 |

| 4/M | 52 | 2+ | 0 | − | 1+ | 40/M | 73 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 |

| 5/F | 66 | 4+ | 1+ | + | 2+ | 41/M | 62 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 |

| 6/M | 70 | 0 | 0 | − | 1+ | 42/M | 70 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 |

| 7/M | 77 | 0 | 0 | − | 1+ | 43/M | 78 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 |

| 8/M | 59 | 0 | 0 | − | 2+ | 44/M | 52 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 |

| 9/F | 41 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 | 45/F | 45 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 |

| 10/F | 64 | 4+ | 3+ | + | 2+ | 46/F | 68 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 |

| 11/F | 63 | 2+ | 1+ | − | 0 | 47/M | 60 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 |

| 12/F | 62 | 0 | 0 | − | 2+ | 48/F | 63 | 3+ | 2+ | − | 1+ |

| 13/F | 71 | 4+ | 4+ | + | 2+ | 49/M | 75 | 2+ | 0 | − | 0 |

| 14/F | 58 | 0 | 0 | − | 1+ | 50/F | 54 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 |

| 15/M | 77 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 | 51/M | 78 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 |

| 16/M | 84 | 0 | 0 | − | 1+ | 52/M | 81 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 |

| 17/M | 59 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 | 53/M | 51 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 |

| 18/F | 72 | 4+ | 4+ | + | 2+ | 54/F | 76 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 |

| 19/M | 76 | 2+ | 0 | − | 2+ | 55/M | 79 | 1+ | 0 | − | 1+ |

| 20/M | 63 | 0 | 0 | − | 1+ | 56/M | 64 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 |

| 21/F | 71 | 1+ | 0 | − | 1+ | 57/F | 69 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 |

| 22/F | 66 | 4+ | 3+ | + | 2+ | 58/F | 63 | 1+ | 0 | − | 1+ |

| 23/F | 79 | 2+ | 0 | − | 2+ | 59/F | 76 | 0 | 0 | − | 1+ |

| 24/M | 81 | 0 | 0 | − | 1+ | 60/M | 81 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 |

| 25/F | 81 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 | 61/F | 86 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 |

| 26/M | 57 | 3+ | 2+ | − | 1+ | 62/M | 53 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 |

| 27/M | 73 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 | 63/M | 71 | 3+ | 0 | − | 0 |

| 28/M | 79 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 | 64/M | 77 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 |

| 29/M | 86 | 4+ | 4+ | + | 2+ | 65/M | 80 | 1+ | 0 | − | 0 |

| 30/M | 58 | 4+ | 2+ | + | 1+ | 66/M | 59 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 |

| 31/M | 60 | 4+ | 0 | + | 1+ | 67/M | 60 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 |

| 32/M | 84 | 4+ | 4+ | + | 1+ | 68/M | 83 | 3+ | 2+ | − | 1+ |

| 33/F | 46 | 4+ | 4+ | + | 1+ | 69/F | 44 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 |

| 34/M | 52 | 3+ | 2+ | − | 1+ | 70/M | 55 | 1+ | 0 | − | 0 |

| 35/M | 69 | 1+ | 0 | − | 1+ | 71/M | 68 | 0 | 0 | − | 0 |

| 36/M | 74 | 4+ | 4+ | + | 1+ | 72/M | 72 | 3+ | 0 | − | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lenders, D.; Aebischer, V.; Gassenmaier, M.; Hahn, M.; Metzler, G.; Forchhammer, S. Nested Melanoma and Superficial Spreading Melanoma with Prominent Nests—A Retrospective Study on Clinical Characteristics and PRAME Expression. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2279. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15172279

Lenders D, Aebischer V, Gassenmaier M, Hahn M, Metzler G, Forchhammer S. Nested Melanoma and Superficial Spreading Melanoma with Prominent Nests—A Retrospective Study on Clinical Characteristics and PRAME Expression. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(17):2279. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15172279

Chicago/Turabian StyleLenders, Daniela, Valentin Aebischer, Maximilian Gassenmaier, Matthias Hahn, Gisela Metzler, and Stephan Forchhammer. 2025. "Nested Melanoma and Superficial Spreading Melanoma with Prominent Nests—A Retrospective Study on Clinical Characteristics and PRAME Expression" Diagnostics 15, no. 17: 2279. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15172279

APA StyleLenders, D., Aebischer, V., Gassenmaier, M., Hahn, M., Metzler, G., & Forchhammer, S. (2025). Nested Melanoma and Superficial Spreading Melanoma with Prominent Nests—A Retrospective Study on Clinical Characteristics and PRAME Expression. Diagnostics, 15(17), 2279. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15172279