1. Introduction

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a rare, chronic cholestatic liver disease characterized by progressive inflammation and fibrotic obliteration of the intra- and/or extrahepatic bile ducts. Over time, this destructive cholangiopathy leads to biliary cirrhosis, portal hypertension, and ultimately liver failure in many patients [

1,

2]. PSC is also strongly associated with an increased risk of hepatobiliary and colorectal malignancies, particularly cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) and colorectal cancer (CRC), the latter primarily among those with concomitant inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [

3,

4]. Despite its rarity, PSC remains a leading indication for liver transplantation in Europe and North America [

5,

6,

7]. The epidemiology of PSC varies geographically. The highest reported incidence rates (1.0–1.5 per 100,000 person-years) are seen in Northern Europe and North America [

4,

8,

9] while Southern and Central–Eastern European countries report lower incidence and prevalence figures [

10,

11,

12,

13]. However, these findings are primarily based on selected patient cohorts from Poland and Austria, rather than population-based epidemiological studies. The current literature is heavily weighted toward populations in Northwestern Europe and the United States, with a notable scarcity of epidemiological and clinical data from Central–Eastern Europe. Given the potential for regional variation in disease expression, comorbidities, and outcomes, additional studies in underrepresented populations are essential.

Risk stratification is also crucial in PSC to identify high-risk patients and guide surveillance, therapy, and transplantation decisions. However, there is currently no universally accepted method for estimating prognosis at the time of PSC diagnosis. The EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG) outline favorable and unfavorable phenotypic, laboratory, and imaging features that may assist non-invasive risk stratification, although their predictive value varies [

8]. Trivedi et al. proposed a risk classification framework based on clinical symptoms, biochemical parameters, liver stiffness measurements, and biliary abnormalities on MRI/MRCP, enabling early identification of patients at significant risk for hepatic decompensation, liver transplantation, or liver-related death [

14,

15].

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP), due to its accessibility and reproducibility, has been extensively studied as a prognostic biomarker [

16,

17,

18]. Although persistently elevated ALP levels are associated with poorer outcomes, the enzyme’s natural variability and inconsistent cut-off thresholds across studies limit its standalone utility. Consequently, current guidelines do not support ALP as a singular prognostic tool [

8].

Historically, risk stratification in PSC has relied on general liver disease models such as the Child–Pugh score and the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD), both of which are limited by their focus on end-stage liver dysfunction and poor performance in early disease stages.

To meet this clinical need, several PSC-specific prognostic models have been developed in the last three decades (Wiesner-1989 [

19], Farrant-1991 [

20], Broome-1996 [

21], revised Mayo Risk Score-2000 [

22], Boberg-2002 [

23], Ponsioen-2002 [

24], Tischendorf-2007 [

25]).

The Revised Mayo Risk Score (rMRS) was designed to predict short-term mortality using simple clinical and biochemical parameters. More recently, the Amsterdam-Oxford Model (AOM) [

26], the UK-PSC risk scores (for short-term and long-term) [

27], and the PSC Risk Estimate Tool (PREsTo) [

28] have expanded the range of predictors and time horizons covered. Prognostic systems fundamentally aim to estimate transplant-free survival—except for PREsTo that predicts decompensation—but the clinical and laboratory parameters used show some differences (

Table 1). Both the UK-PSC and AOM have proven to be reliable [

29,

30], and were also shown to be prognostic in recurrent cases [

31]. However, only a limited number of comparative studies have been conducted.

This study provides epidemiological data from the Central–Eastern European region, while also evaluating and comparing the performance of major PSC-specific risk scores over time, and explores the prognostic utility of ALP in a Hungarian bicenter cohort.

4. Discussion

Over the past several decades, numerous population-based studies have characterized the epidemiology and natural history of PSC in North America and Northwestern Europe [

21,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. In contrast, data from other global regions—including Central and Eastern Europe—remain limited. Our study addresses this regional data gap by providing the first population-based clinical and prognostic insights into PSC from a Hungarian cohort. Among Central European countries, most previously available epidemiologic insights originate from Austria and Poland, with findings largely consistent across studies regarding sex distribution, mean age at diagnosis, and the prevalence of IBD and cirrhosis [

10,

11,

12,

44]. However, compared to certain Polish cohorts, our study observed a lower prevalence of IBD and fewer patients undergoing liver transplantation [

10,

11,

44]. These discrepancies may stem from differences in study design and selection criteria, as prior investigations were not explicitly epidemiological in nature. In our cohort, 54.1% of patients had concurrent IBD, a lower rate than the >60% typically reported in Western European cohorts [

45]. Nonetheless, IBD preceded the diagnosis of PSC in over 80% of these patients, consistent with existing literature [

6]. The higher transplantation rate in PSC-IBD patients may reflect earlier recognition and/or more proactive management rather than intrinsically worse liver disease, as cirrhosis development rates were similar between groups. While a few studies reported worse outcomes in patients with PSC-IBD [

46] or specifically PSC-UC [

47], most studies demonstrate comparable outcome rates regardless of IBD status [

48,

49,

50]. Consistently, our study found similar composite outcome rates between groups, supporting the role of timely transplantation.

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) was identified in 4.4% of patients, which is at the lower end of the 8–13% range reported in large cohorts. However, this rate aligns with findings from several European studies reporting similarly low CCA incidences, such as those from Austria (3.3%), France (4.0%), Italy (2.2%), and Finland (4.5%) [

12,

36,

51,

52]. In contrast, studies from other Western European and Scandinavian countries tend to report higher CCA rates among patients with PSC. Notably, a large international study involving 37 centers across 17 countries found a CCA incidence of only 7.48%, further supporting the presence of regional variation [

47]. This geographic discrepancy suggests that underlying genetic, environmental, lifestyle, or healthcare system-related factors may influence the detected incidence of CCA in PSC patients. Further studies are warranted to clarify the determinants of these regional differences, including the potential impact of varying screening practices, diagnostic approaches, and biological predispositions. There were no significant differences in CCA occurrence between PSC-only and PSC-IBD patients. However, colorectal cancer occurred exclusively in the PSC-IBD group, reinforcing its strong association with long-standing colonic inflammation in this population [

53]. PSC-AIH overlap syndrome occurs in 7-14% of cases [

8], which is in line with our data (12.5%). Only 2 (11%) of the PSC-AIH patients were confirmed to have small duct PSC, which is significantly lower than expected [

8].

ALP, despite its high variability, is well-suited for prognostic purposes when interpreted in the appropriate context. In addition to the development of the UK-PSC scoring system, Goode and colleagues also formulated the independent predictive function of ALP in their study. Improved transplant-free survival results were found, when ALP decreased to <2.4 × ULN and <2.2 × ULN at 1 and 2 years following diagnosis, respectively [

27]. Our study validates these findings, demonstrating that persistent ALP elevation despite UDCA treatment —considering these cut-off values—can serve as a valuable marker for transplantation and mortality risk assessment tools. Moreover, in our cohort, this single biomarker outperformed composite scores in predicting 10-year composite outcome. Notably, new therapies are being investigated for reducing ALP levels in PSC including fenofibrate [

54], elafibranor (a dual peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α/δ agonist) [

55], and cenicriviroc (a dual antagonist of C-C chemokine receptor types 2 and 5) [

56]; however their long-term impact on survival still needs to be evaluated.

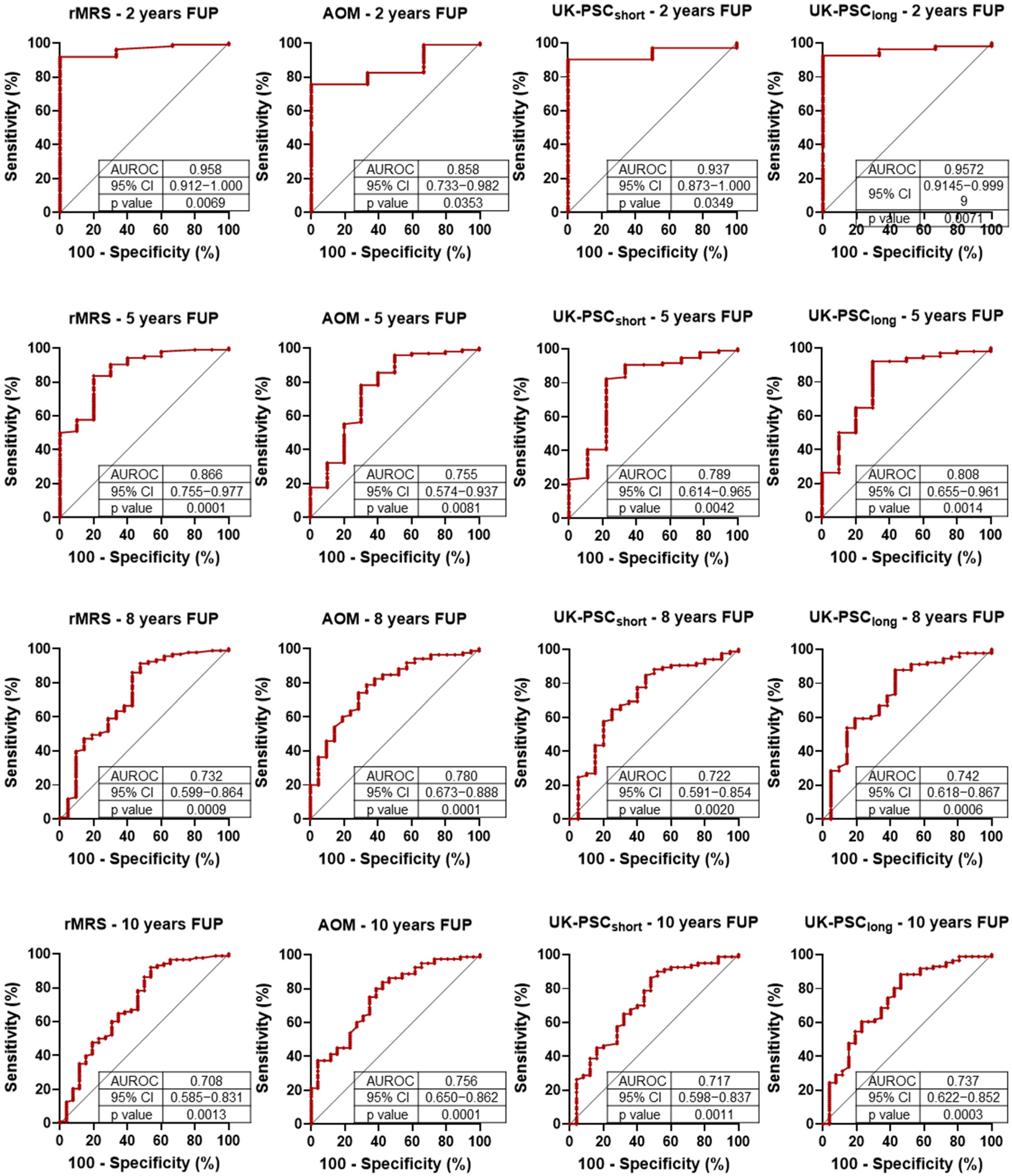

To date, few studies have compared PSC-specific prognostic scoring systems directly within a single cohort. A major strength of our study is the head-to-head, longitudinal evaluation of the most widely used models: the revised rMRS, the AOM, and the UK-PSC score. This allowed us to assess and contrast their short- and long-term predictive capacities over time. Validation studies of the newer prognostic scoring systems showed excellent predictive value for the UK-PSC score (AUROC: 0.81 and 0.80 for short- and long-term, respectively), while the Amsterdam-Oxford Model (AUROC: 0.67 (95% CI 0.64–0.70) also demonstrated reliable performance [

27,

28,

57,

58]. In a study investigating soluble macrophage markers, the rMRS and the AOM performed similarly for predicting 8-year transplant-free survival [

59]. In our study, the rMRS had the highest early AUROC but declined more sharply over time. The AOM model showed the most stable performance and may be particularly well-suited for long-term stratification. In our cohort, the UK-PSC short-term risk score demonstrated lower predictive performance compared to other prognostic models and to its originally published validation metrics. A decline in the accuracy of all scoring systems over extended follow-up was also observed. This temporal decrease in prognostic discrimination is likely multifactorial. In early disease stages—characterized by biochemical fluctuations and heterogeneous progression—it remains challenging to reliably estimate disease trajectory, even with sophisticated composite scoring systems. In contrast, once advanced liver disease manifests, clinical endpoints become more predictable and more easily captured by risk algorithms. These findings underscore the limitations of current models in forecasting long-term outcomes from early disease data and highlight the need for dynamic or longitudinally adaptive scoring approaches. Our results confirm the conclusion already suggested by the literature: despite their differences, all three scoring systems (RMS, UK-PSC, AOM) can be reliably used for risk assessment. In the ROC analysis, we did not observe significant differences between them; however, the similarity of the results may be influenced by the sample size of our cohort, which limits the granularity of the assessment.

In summary, our study provides data on the clinical profile and prognosis of PSC in Hungary addressing a key regional data gap in Central–Eastern Europe, and offers the first direct, longitudinal comparison of major PSC-specific prognostic models within the same cohort. It also confirms the utility of ALP, particularly persistent elevation above 2.2 × ULN, as a robust predictor of long-term outcomes. Despite its strengths, our study has some limitations including the retrospective design and the relatively small sample size. However, the population-based nature of the data might mitigate these limitations and enhance its real-world relevance.