Vulvar Hemangioma: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

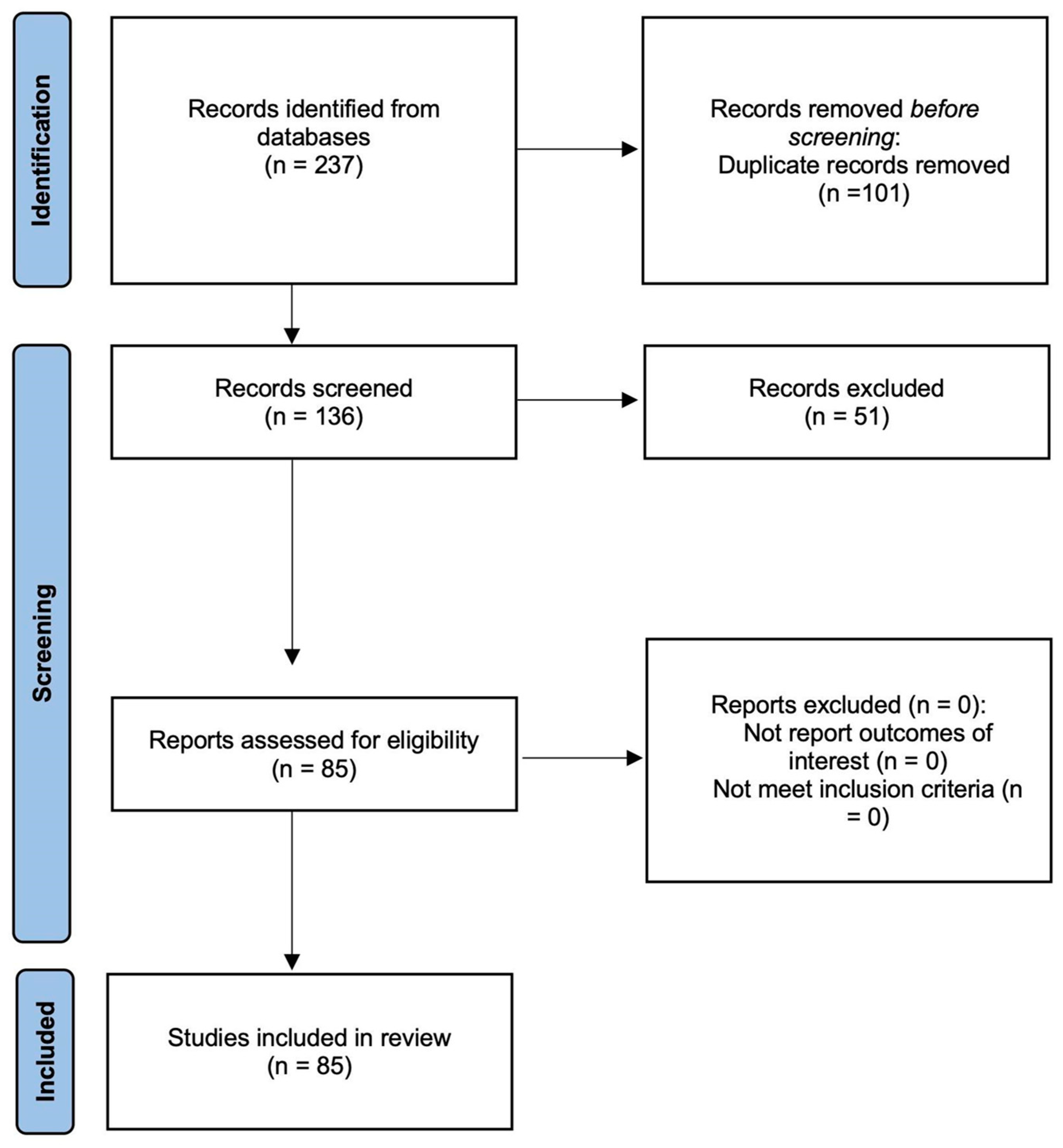

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

2.3. The Selection Process

3. Result

3.1. Screening Results

3.2. Case Reports and Literature Review

4. Discussion

4.1. Definition of Vulvar Hemangioma

4.2. Clinical Significance and Impact on Quality of Life

4.3. Pathophysiology

4.3.1. Development of Vascular Malformations

4.3.2. Differences Between Hemangiomas and Vascular Malformations

4.3.3. Possible Genetic and Hormonal Influences

4.4. Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

4.4.1. Symptoms and Signs

4.4.2. Classification of Hemangiomas

4.4.3. Differential Diagnosis

4.4.4. Imaging Modalities

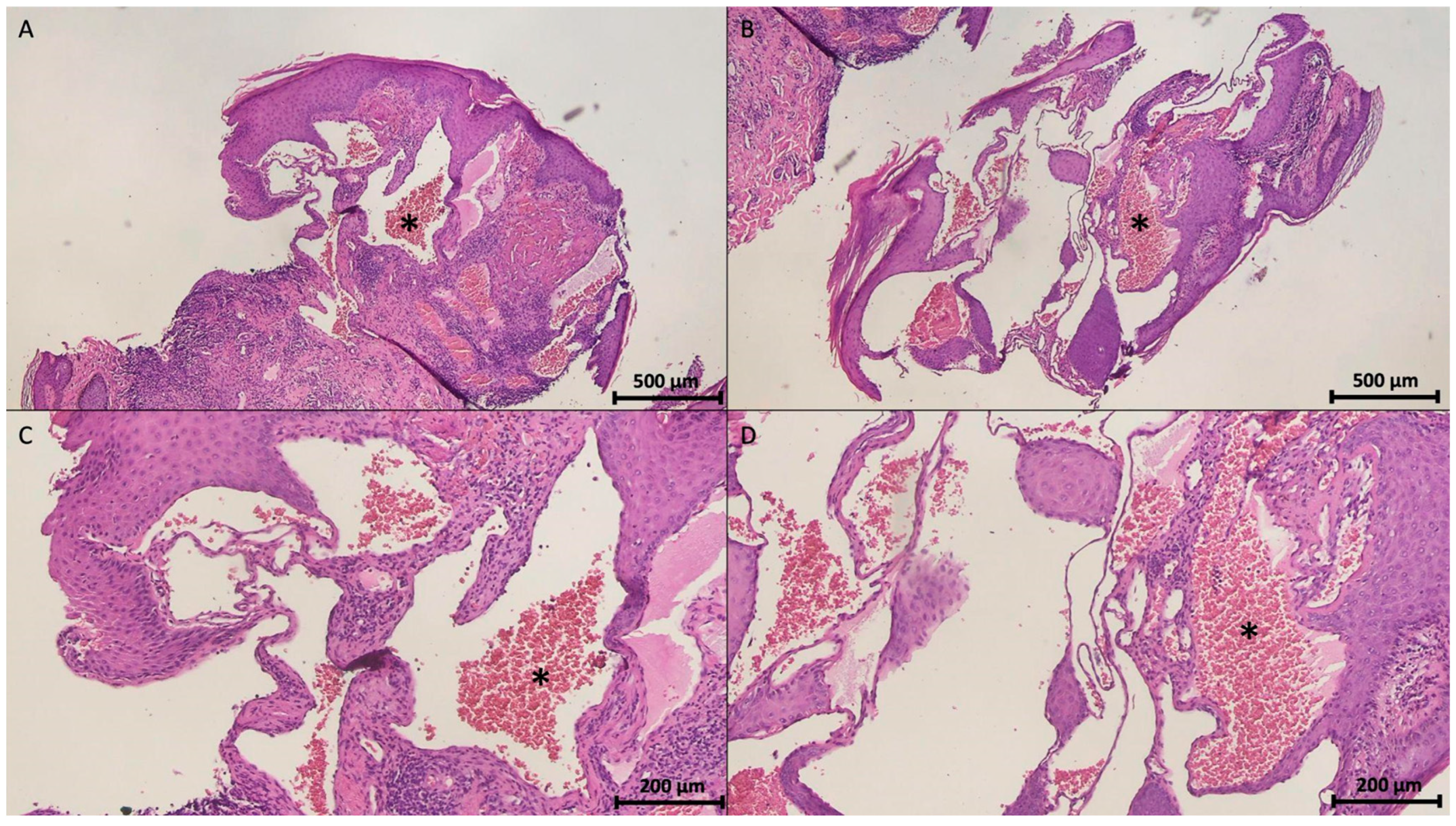

4.4.5. Histopathological Features

4.5. Management and Treatment Options

4.5.1. Conservative Management

4.5.2. Medical Therapy

Beta-Blockers

Corticosteroids

Sclerotherapy

4.5.3. Surgical and Minimally Invasive Interventions

Laser Therapy

Cryotherapy

Surgical Excision

4.6. Prognosis and Complications

4.6.1. Natural Course and Probability of Spontaneous Resolution

4.6.2. Potential Complications

4.6.3. Long-Term Outcomes and Recurrence Rates

4.7. Research Gaps and Future Directions

4.7.1. Need for Standardized Treatment Guidelines

4.7.2. Advances in Targeted Therapies

4.7.3. Role of Genetic and Molecular Studies in Understanding Pathogenesis

4.8. Summary of the Above Findings (Table 4)

| Variables | Main Findings |

|---|---|

| General characteristics of presentation of vulvar hemangiomas |

|

| Clinical presentation and symptoms |

|

| Image diagnosis of vulvar hemangiomas |

|

| Immunohistochemical characteristics |

|

| New perspectives on therapy |

|

| Research gaps and future directions |

|

4.9. Comparison with One Previous Study

4.10. Strengths and Weaknesses

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cebesoy, F.B.; Kutlar, I.; Aydin, A. A Rare Mass Formation of the Vulva: Giant Cavernous Hemangioma. J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis. 2008, 12, 35–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, J.M.; Calife, E.R.; Cabral, J.V.d.S.; de Andrade, H.P.F.; Gonçalves, A.K. Vulvar Hemangioma: Case Report. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. 2018, 40, 369–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, V.Y.T.; Tse, K.Y. Vulval Hemangioma. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2018, 40, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Si, W.; Zou, Z.; Li, B.; Mu, Y.; Zhong, W.; Yang, K. Efficacy and Safety of Oral Propranolol and Topical Timolol in the Treatment of Infantile Hemangioma: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1515901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, M.L.; Fleischer, A.B., Jr.; Chamlin, S.L.; Frieden, I.J. Oral Corticosteroid Use Is Effective for Cutaneous Hemangiomas: An Evidence-Based Evaluation. Arch. Dermatol. 2001, 137, 1208–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu-Dos-Santos, F.; Câmara, S.; Reis, F.; Freitas, T.; Gaspar, H.; Cordeiro, M. Vulvar Lobular Capillary Hemangioma: A Rare Location for a Frequent Entity. Case Rep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 2016, 3435270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basta, M.S.T.; Sharma, K.; Chauhan, M. Be Wary, This Is Not a Case of Vulval Warts! Int. J. STD AIDS 2008, 19, 213–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bava, G.L.; Dalmonte, P.; Oddone, M.; Rossi, U. Life-Threatening Hemorrhage from a Vulvar Hemangioma. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2002, 37, E6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, V.; Pontello, V.; Dei, M.; Alessandrini, M.; Li Marzi, V.; Nicita, G. Hemangioma of the Clitoris Presenting as Clitoromegaly: A Case Report. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2009, 22, e137–e138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djunic, I.; Elezovic, I.; Ljubic, A.; Markovic, O.; Tomin, D.; Tadic, J. Diffuse Cavernous Hemangioma of the Left Leg, Vulva, Uterus, and Placenta of a Pregnant Woman. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2009, 107, 250–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhu, C.; Khaled, M.A.; Putran, J. Vulval Haemangioma in an Adolescent Girl. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2011, 31, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondal, P.C.; Chakraborty, B.; Mandal, D.; Char, D.; Sahana, R.; Murmu, S.S. Vulvar Pyogenic Granuloma (lobular Capillary Hemangioma). J. Reprod. Med. 2017, 62, 92–94. [Google Scholar]

- Nayyar, S.; Liaqat, N.; Sultan, N.; Dar, S.H. Cavernous Haemangioma Mimicking as Clitoral Hypertrophy. Afr. J. Paediatr. Surg. 2014, 11, 65–66. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, M.S.; Gibu, S.G.; Kizito, M.S. A Rare Case of a 5-Year-Old Girl with Klippel-Trénaunay Syndrome and a Bleeding Focal Vulvar Hemangioma in Uganda. Clin. Case Rep. 2024, 12, e9501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merlino, L.; Volpicelli, A.I.; Anglana, F.; D’Ovidio, G.; Dominoni, M.; Pasquali, M.F.; Gardella, B.; Inghirami, P.; Lippa, P.; Senatori, R. Pediatric Hemangiomas in the Female Genital Tract: A Literature Review. Diseases 2024, 12, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarou, G.; Goldberg, M.I. Vulvar Arteriovenous Hemangioma. A Case Report. J. Reprod. Med. 2000, 45, 439–441. [Google Scholar]

- Hickey, S.; Bell, H. Quality of Life in the Vulvar Clinic: A Pilot Study. J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis. 2010, 14, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, J.M.; Chamlin, S.L. Quality of Life in Vascular Anomalies. Lymphat. Res. Biol. 2005, 3, 256–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, G.T.; Friedman, A.B. Hemangiomas and Vascular Malformations: Current Theory and Management. Int. J. Pediatr. 2012, 2012, 645678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondi-Pafiti, A.; Kairi-Vassilatou, E.; Spanidou-Carvouni, H.; Kontogianni, K.; Dimopoulou, K.; Goula, K. Vascular Tumors of the Female Genital Tract: A Clinicopathological Study of Nine Cases. Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2003, 24, 48–50. [Google Scholar]

- Chiller, K.G.; Frieden, I.J.; Arbiser, J.L. Molecular Pathogenesis of Vascular Anomalies: Classification into Three Categories Based upon Clinical and Biochemical Characteristics. Lymphat. Res. Biol. 2003, 1, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, B.; Banyard, J.; McLaughlin, E.R.; Watnick, R.; Sohn, A.; Brindley, D.N.; Obata, T.; Cantley, L.C.; Cohen, C.; Arbiser, J.L. AKT1 Overexpression in Endothelial Cells Leads to the Development of Cutaneous Vascular Malformations in Vivo. Arch. Dermatol. 2007, 143, 504–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wildgruber, M.; Sadick, M.; Müller-Wille, R.; Wohlgemuth, W.A. Vascular Tumors in Infants and Adolescents. Insights Imaging 2019, 10, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, K.; Singh, L.; Khan, N.A.; Goyal, S.; Khatri, A.; Gupta, N. Benign Vascular Anomalies: A Transition from Morphological to Etiological Classification. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2020, 46, 151506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Raggal, N.M.; El-Farrash, R.A.; Saad, A.A.; Attia, E.A.S.; Saafan, H.A.; Shaaban, I.S. Circulating Levels of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor and Basic Fibroblastic Growth Factor in Infantile Hemangioma versus Vascular Malformations. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2018, 24, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCuaig, C.C. Update on Classification and Diagnosis of Vascular Malformations. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2017, 29, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchuk, D.A. Pathogenesis of Hemangioma. J. Clin. Investig. 2001, 107, 665–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Htwe, M.; Deppisch, L.M.; Saint-Julien, J.S. Hormone-Dependent, Aggressive Angiomyxoma of the Vulva. Obstet. Gynecol. 1995, 86, 697–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cunha Filho, R.; de Almeida, H.L., Jr. Acquired Iatrogenic Vulvar Lymphangioma. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2009, 23, 466–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmdahl, K. Cutaneous Hemangiomas in Premature and Mature Infants. Acta Paediatr. 1955, 44, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez Bandera, A.I.; Sebaratnam, D.F.; Wargon, O.; Wong, L.-C.F. Infantile Hemangioma. Part 1: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Clinical Presentation and Assessment. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2021, 85, 1379–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahrman, J.E.; Honig, P.J. Hemangiomas. Pediatr. Rev. 1994, 15, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Tavares, K.A.; Moscovitz, T.; Tcherniakovsky, M.; Pompei, L.d.M.; Fernandes, C.E. Differential Diagnosis Between Bartholin Cyst and Vulvar Leiomyoma: Case Report. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. 2017, 39, 433–435. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neal, M.F.; Amparo, E.G. MR Demonstration of Extensive Pelvic Involvement in Vulvar Hemangiomas. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 1988, 12, 219–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhardt, S.; Rolston, R.; Palmer, S.; Ozel, B. Vaginal Angiomyofibroblastoma: A Case Report and Review of Diagnostic Imaging. Case Rep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 2018, 7397121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silpa, S.R.; Cicy, P.J.; Sankar, S. Pedunculated Vulvar Hemangioma: A Rare Case Report. Saudi J. Pathol. Microbiol. 2022, 7, 170–172. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Yin, X.; Yao, W.; Liu, N.; Yue, Y. Retiform Hemangioendothelioma: A Rare Lesion of the Vulva. J. Int. Med. Res. 2021, 49, 3000605211027783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartin, T.L.; Sitler, C.A. A Case of Vulvar Cavernous Lymphangioma. Hawaii J. Health Soc. Welf. 2019, 78, 356–358. [Google Scholar]

- Trindade, F.; Torrelo, A.; Kutzner, H.; Requena, L.; Tellechea, Ó.; Colmenero, I. An Immunohistochemical Study of Angiokeratomas of Children. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2014, 36, 796–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Roggen, J.F.G.; van Unnik, J.A.M.; Briaire-de Bruijn, I.H.; Hogendoorn, P.C.W. Aggressive Angiomyxoma: A Clinicopathological and Immunohistochemical Study of 11 Cases with Long-Term Follow-Up. Virchows Arch. 2005, 446, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Lee, H.; Lee, H.; Park, S.Y.; Chung, J.-H.; Choe, G.; Kim, W.; Song, K. Immunohistochemical Characteristics of Kaposi Sarcoma and Its Mimicries. Korean J. Pathol. 2006, 40, 361–367. [Google Scholar]

- Ichiki, T.; Yamada, Y.; Ito, T.; Nakahara, T.; Nakashima, Y.; Nakamura, M.; Yoshizumi, T.; Shiose, A.; Akashi, K.; Oda, Y. Histological and Immunohistochemical Prognostic Factors of Primary Angiosarcoma. Virchows Arch. 2023, 483, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Navarro, L.; March-Rodriguez, Á.; Planella-Fontanillas, N.; Pujol, R.M. Infantile Hemangiomas of the Vulvar Region: A Therapeutic Challenge. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2025, 116, T316–T319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browning, J.; Frieden, I.; Baselga, E.; Wagner, A.; Metry, D. Congenital, Self-Regressing Tufted Angioma. Arch. Dermatol. 2006, 142, 749–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd Elnaby, S.; Sultan, T.; Abd Elaziz, T. Topical Timolol versus Oral Propranolol for the Treatment of Hemangioma in Children. Menoufia Med. J. 2021, 34, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.; Lloyd, M.S. Propranolol for Surgeons in the Treatment of Infantile Hemangiomas. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2020, 31, 134–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatt, J.; Morrell, D.S.; Buck, S.; Zdanski, C.; Gold, S.; Stavas, J.; Powell, C.; Burkhart, C.N. Β-Blockers for Infantile Hemangiomas: A Single-Institution Experience. Clin. Pediatr. 2011, 50, 757–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberger, S.; Boscolo, E.; Adini, I.; Mulliken, J.B.; Bischoff, J. Corticosteroid Suppression of VEGF-A in Infantile Hemangioma-Derived Stem Cells. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1005–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, C.L.; Sanfilippo, J.S.; Verdi, G.D.; Pietsch, J.B. Capillary Hemangioma of the Vagina and Urethra in a Child: Response to Short-Term Steroid Therapy. Obstet. Gynecol. 1989, 73, 883–885. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, H.; Dräger, E.; Sterry, W. Sclerotherapy for Treatment of Hemangiomas. Dermatol. Surg. 2000, 26, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ninia, J.G. Treatment of Vulvar Varicosities by Injection-Compression Sclerotherapy. Dermatol. Surg. 1997, 23, 573–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, C.; Khurana, A.; Bhattacharya, S.N. Sclerotherapy for the Treatment of Infantile Hemangiomas. J. Cutan. Aesthet. Surg. 2012, 5, 201–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuoka, M.; Okumura, T.; Hayashi, A.; Takeda, N.; Koizumi, A.; Ujihira, T.; Makino, S. A Case of a Refractory Bleeding Giant Vaginal Wall Cavernous Hemangioma Successfully Managed with Sclerotherapy. Am. J. Case Rep. 2023, 24, e939474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, R.; Negishi, K.; Akita, H.; Suzuki, K.; Matsunaga, K. Successful Treatment of Congenital Lymphangioma Circumscriptum of the Vulva with CO2 and Long-Pulsed Nd:YAG Lasers. Case Rep. Dermatol. 2014, 6, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderón-Castrat, X.; Santos-Durán, J.C.; Román-Curto, C.; Fernández-López, E. Carbon Dioxide Laser: A Therapeutic Approach for Multiple Vulvar Epidermoid Cysts. Dermatol. Surg. 2016, 42, 264–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Desai, M.; Elsensohn, A.; Kraus, C.N. A Systematic Review of Laser Therapy for Vulvar Skin Conditions. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2023, 88, 1200–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belotto, R.; Santos, R.E.; Tardivo, J.P.; Fernandes, R.; Baptista, M.; Itri, R.; Chavantes, M.C. Photodynamic Therapy in Vulvar Lymphangioma: Case Report. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2019, 25, 84–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanazume, S.; Douzono, H.; Kubo, H.; Nagata, T.; Douchi, T.; Kobayashi, H. Cryotherapy for Massive Vulvar Lymphatic Leakage Complicated with Lymphangiomas Following Gynecological Cancer Treatment. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 44, 1116–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robati, R.M.; Ghasemi-Pour, M. Efficacy and Safety of Cryotherapy vs. Electrosurgery in the Treatment of Cherry Angioma. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2018, 32, e361–e363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayasari, P.S.; Djawad, K.; Nurdin, A.; Mappangara, I.; Suryajaya, P.I. Comparison of CO2 Laser and Cryotherapy for Clinical Improvement in Vascular Tumor Lesions in Patients with Klippel Trenaunay Syndromes: A Rare Case. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 178–182. [Google Scholar]

- Tiemann, L.; Hein, S. Infantile Hemangioma: A Review of Current Pharmacotherapy Treatment and Practice Pearls. J. Pediatr. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 25, 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brook, I. Microbiology of Infected Hemangiomas in Children. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2004, 21, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Dong, C.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, X.; Zuo, S.; Zhang, H. The Sustained and Targeted Treatment of Hemangiomas by Propranolol-Loaded CD133 Aptamers Conjugated Liposomes-in-Microspheres. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 114, 108823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, N.; Ding, X.; Jahan, R. Low Concentration of Rapamycin Inhibits Hemangioma Endothelial Cell Proliferation, Migration, and Vascular Tumor Formation in Mice. Curr. Ther. Res. Clin. Exp. 2014, 76, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Yang, Z.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, Z.; Yang, X. Identification of Potential Therapeutics for Infantile Hemangioma via in Silico Investigation and in Vitro Validation. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2024, 18, 4065–4088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholtz, W.; Mabeta, P. Sunitinib Malate Inhibits Hemangioma Cell Growth and Migration by Suppressing Focal Adhesion Kinase Signaling. J. Appl. Biomed. 2020, 18, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liau, J.-Y.; Lee, J.-C.; Tsai, J.-H.; Chen, C.-C.; Chung, Y.-C.; Wang, Y.-H. High Frequency of GNA14, GNAQ, and GNA11 Mutations in Cherry Hemangioma: A Histopathological and Molecular Study of 85 Cases Indicating GNA14 as the Most Commonly Mutated Gene in Vascular Neoplasms. Mod. Pathol. 2019, 32, 1657–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habeeb, O.; Rubin, B.P. The Molecular Diagnostics of Vascular Neoplasms. Surg. Pathol. Clin. 2019, 12, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, P.; Bergstrom, K.L.; Phung, T.L.; Metry, D.W. The Genetics of Vascular Birthmarks. Clin. Dermatol. 2022, 40, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrence, D.; Antonescu, C.R. The Genetics of Vascular Tumours: An Update. Histopathology 2022, 80, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Items | Specification |

|---|---|

| Timeframe | From inception to 20 February 2025 |

| Database | PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Embase |

| Search term used | “vulvar hemangioma” |

| Inclusion and exclusion criteria | SCI-indexed articles written in English. Reviews, editorials, and studies unrelated to vulvar hemangiomas were excluded. |

| Selection process | Two independent reviewers evaluate the titles and abstracts to determine eligibility. |

| Author, Year of Publication | Age (Years) | Parity | Past Medical History | Signs and Symptoms | Lesion Size | Treatment | Pathology/ Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abreu-Dos-Santos et al., 2016 [7] | 51 | 3 | Hypertension and hyperthyroidism | It looks like a small wart | 2 cm long | Wide excision | Vulvar hemangioma |

| Besta et al., 2008 [8] | 40 | NA | Cervical spondylosis, right torticollis, capsulitis of the right shoulder, and seizure | Recurrent non-painful vulval lumps | 2 cm | Biopsy | Cavernous hemangioma |

| Beva et al., 2002 [9] | 1 | NA | NA | Significant local bleeding caused by deep ulcerations | NA | Embolization | Immature capillary hemangioma |

| Bruni et al., 2009 [10] | 20 | NA | Mild allergic asthma, oligomenorrhea | Clitoromegaly | 5 × 3 cm | Excision | Cavernous hemangioma |

| Cebesoy et al., 2008 [1] | 26 | NA | NA | Sexual dysfunction, pain, pressure | Covering the labia major | Excision | Cavernous hemangioma |

| Cheung et al., 2018 [3] | 63 | NA | NA | Discomfort and multiple purple-blue swellings were noted | Involving almost the whole of the right labia majora | No treatment | Cavernous hemangioma |

| Djunic et al., 2009 [11] | 33 | Preg 26 weeks | NA | Low-grade disseminated intravascular coagulation during pregnancy | Involving the left leg, including the foot, lower leg, and femoral region, as well as the left gluteal region and the left labia major and minor | Low-molecular-weight heparin | Cavernous hemangioma |

| Madhu et al., 2011 [12] | 13 | NA | Left breast cyst post cystectomy | Vulva swelling | 1 × 1 cm | Excision | Benign hemangiomata |

| Mondal et al., 2017 [13] | 42 | NA | NA | Rapidly growing, glistening, ulcerative, pedunculated vulvar mass | NA | Excision | Lobular capillary hemangioma |

| Nayyar et al., 2014 [14] | 10 | NA | Her family history was not significant, and there was no history of any medication | Clitoromegaly | 6 × 2.5 cm | Biopsy | Cavernous hemangioma |

| Peter et al., 2024 [15] | 5 | NA | Klippel–Trénaunay syndrome | Bleeding vulvar hemangioma | Located at left labia minora | Compression bandaging and timolol 0.2% solution | Hemangioma |

| Silva et al., 2018 [2] | 52 | NA | Prediabetes, dyslipidemia, and premenopausal | Genital ulcer for the past 3 years | Located at the perineal body | Creams and ointments, biopsy, surgical excision | Vulvar hemangioma |

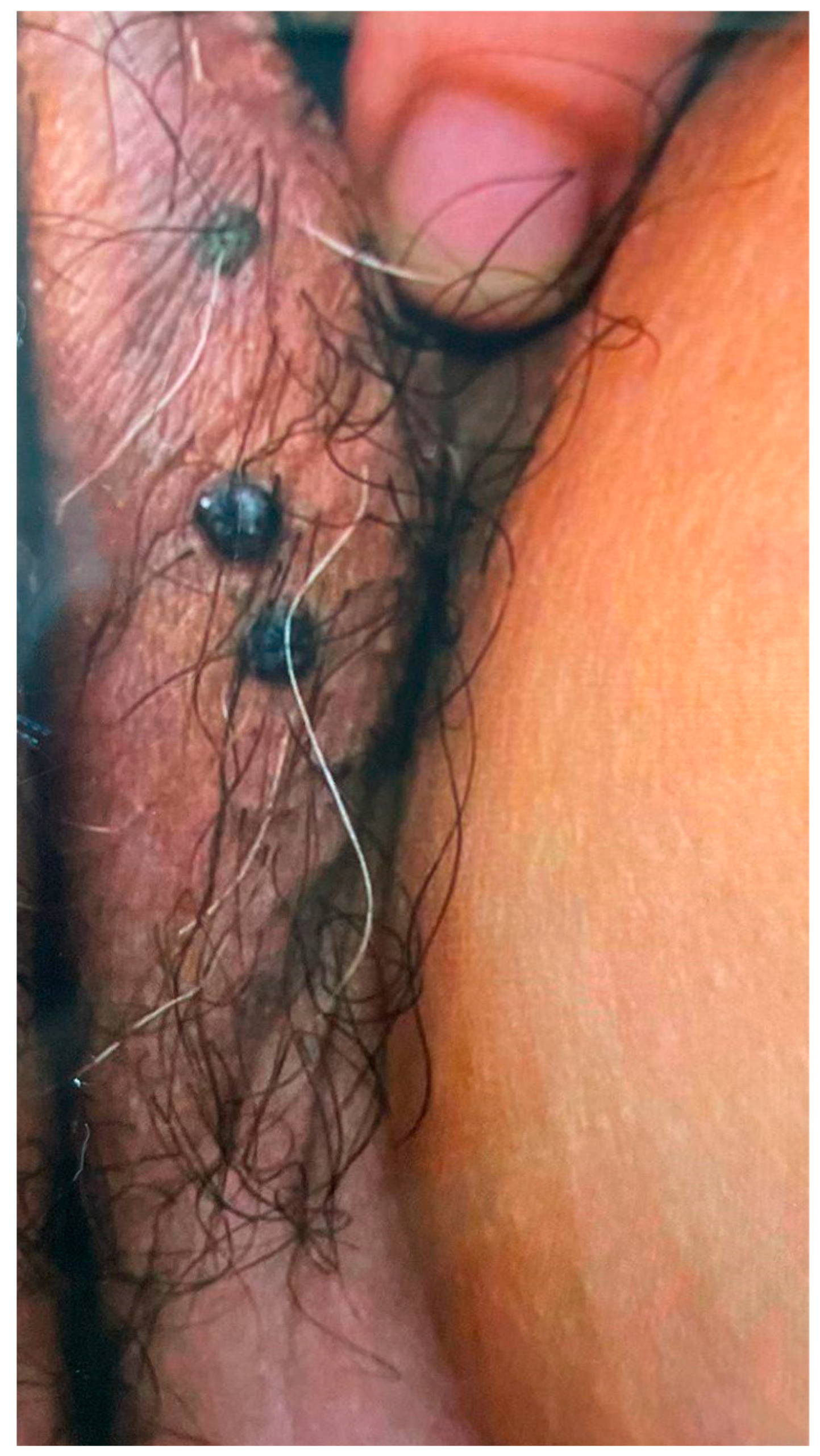

| Current study | 69 | 2 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension | Vulva nodules | Two small nodules | No treatment | Cavernous hemangioma |

| Entity | Histopathological Features | Immunohistochemical Profile | Key Differential Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cavernous Hemangioma (typical vulvar type) |

| CD31+ CD34+ FLI-1+ GLUT-1− (in adults) D2-40− | Benign; compressible; lacks nuclear atypia or infiltrative borders |

| Lymphangioma [39] |

| D2-40+ CD31+ PROX1+ ± CD34 GLUT-1− | Clear or yellowish vesicles Absence of blood-filled spaces Positive D2-40 helps differentiate |

| Angiokeratoma [40] |

| CD31+ CD34+ GLUT-1− | Typically smaller, superficial Black or purple “wart-like” lesions Marked epidermal changes |

| Aggressive Angiomyxoma [41] |

| Desmin+ ER/PR+ CD34+ (variable) ± SMA+ GLUT-1− | Deep, infiltrative mass Recurring locally Often ER/PR positive; not purely vascular |

| Kaposi Sarcoma (vascular malignancy) [42] |

| CD31+ CD34+ HHV-8+ ± D2-40 | Malignant; shows atypia, mitoses HHV-8 positive is diagnostic |

| Angiosarcoma (vascular malignancy) [43] |

| CD31+ ERG+ CD34+ ± Factor VIII+ GLUT-1− | Highly aggressive Distorted architecture High nuclear grade and mitoses |

| Aspect | Our Study | Pediatric Study Summary |

|---|---|---|

| Population Focus | Primarily adult women with vulvar hemangiomas | Pediatric patients, especially with vulvovaginal and uterine hemangiomas |

| Hemangioma Types | Includes cavernous, arteriovenous, and lobular capillary hemangiomas | Focuses on infantile hemangiomas (IHs) and congenital hemangiomas (CHs) |

| Anatomical Focus | Vulvar lesions, particularly in the labia majora | Cervicovaginal and uterine lesions are more frequently described |

| Diagnostic Modalities | Emphasizes clinical exam, Doppler ultrasound, MRI, and histopathology with IHC | Similar imaging tools; highlight vaginoscopy, cystoscopy, and GLUT-1 staining for IHs |

| Immunohistochemistry | Uses CD31, CD34, FLI-1; GLUT-1 typically negative in adult lesions | GLUT-1 positive is a key marker for infantile hemangiomas |

| Treatment Options | Comprehensive: observation, beta-blockers, corticosteroids, sclerotherapy, laser, cryotherapy, excision | Propranolol as first-line; corticosteroids second-line; surgery for refractory or large lesions |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siu, W.-Y.S.; Chen, Y.-C.; Ding, D.-C. Vulvar Hemangioma: A Review. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1270. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15101270

Siu W-YS, Chen Y-C, Ding D-C. Vulvar Hemangioma: A Review. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(10):1270. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15101270

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiu, Wing-Yu Sharon, Yen-Chang Chen, and Dah-Ching Ding. 2025. "Vulvar Hemangioma: A Review" Diagnostics 15, no. 10: 1270. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15101270

APA StyleSiu, W.-Y. S., Chen, Y.-C., & Ding, D.-C. (2025). Vulvar Hemangioma: A Review. Diagnostics, 15(10), 1270. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15101270