Abstract

Background: Crohn’s disease (CD) is a complex systemic entity, characterized by the progressive and relapsing inflammatory involvement of any part of the gastrointestinal tract. Its clinical pattern may be categorized as penetrating, stricturing or non-penetrating non-stricturing. Methods: In this paper, we performed a database search (Pubmed, MEDLINE, Mendeley) using combinations of the queries “crohn”, “stricture” and “elastography” up to 19 June 2024 to summarize current knowledge regarding the diagnostic utility of ultrasound (US) and magnetic resonance (MR) elastography techniques in the evaluation of stricturing CD by means of an assessment of the transmural intestinal fibrosis. We decided to include papers published since 1 January 2017 for further evaluation (n = 24). Results: Despite growing collective and original data regarding numerous applications of mostly ultrasound elastography (quantification of fibrosis, distinguishing inflammatory from predominantly fibrotic strictures, assessment of treatment response, predicting disease progression) constantly emerging, to date, we are still lacking a uniformization in both cut-off values and principles of measurements, i.e., reference tissue in strain elastography (mesenteric fat, abdominal muscles, unaffected bowel segment), units, not to mention subtle differences in technical background of SWE techniques utilized by different vendors. All these factors imply that ultrasound elastography techniques are hardly translatable throughout different medical centers and practitioners, largely depending on the local experience. Conclusions: Nonetheless, the existing medical evidence is promising, especially in terms of possible longitudinal comparative studies (follow-up) of patients in the course of the disease, which seems to be of particular interest in children (lack of radiation, less invasive contrast media) and terminal ileal disease (easily accessible).

1. Introduction

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a complex systemic entity, characterized by the progressive and relapsing inflammatory involvement of any part of the gastrointestinal tract. Its clinical pattern may be categorized as penetrating, stricturing or non-penetrating non-stricturing. In stricturing disease, both inflammation and fibrosis contribute to an abnormal narrowing of the intestinal lumen (inflammatory, fibrotic and mixed strictures), with excessive extracellular protein (mainly collagen) deposition. The inflammatory process involves all layers of the intestinal wall and may further progress into transmural fibrotic stenosis, resulting from the uncontrolled and excessive healing process due to the activation of myofibroblasts and a distortion of the mural cytoarchitecture. By definition, a stricture is a localized obstruction of the intestinal lumen by at least 50% compared to the normal segment, accompanied by an apparent upstream dilatation ≥3 cm. In clinical terms, intestinal strictures present as obstructive symptoms, i.e., abdominal cramping, loss of appetite, vomiting, constipation, largely affecting the quality of life and requiring surgical intervention in a substantial percentage of patients [1].

Since to date, no effective anti-fibrotic non-invasive treatment exists, especially for late-stage disease, fibrotic strictures require mechanical interventions, e.g., hemicolectomy or segmental resection, strictureplasty and balloon dilation. On the contrary, inflammatory lesions are easily targeted by means of pharmacological treatment, including anti-inflammatory, immunosuppressive (azathioprine) and biologic (adalimumab) agents. As the inflammatory and fibrostenotic stricturing disease requires a different therapeutic approach, identifying the main component underlying intestinal obstruction by non-invasive means is pivotal in terms of patient’s clinical management [1].

Although conventional cross-sectional imaging (CT and MR enterography) may provide considerable amounts of information regarding the disease burden (extension, activity, intestinal motility), its role is still limited in identifying the leading histopathological cause of strictures. In particular, inflammation and fibrosis concomitantly contribute to strictures in varying proportions in a majority of cases [1]. Herein, diagnostic imaging vendors are in constant search for new technologies that would provide quantitative measures for assessing the level of fibrosis within the affected intestinal loop and thus indicate proper therapeutic strategy. It is stated that sonoelastography meets the above needs, being a promising tool in the evaluation of patients with CD as it can differentiate inflammatory and fibrotic strictures [2].

2. Methodology

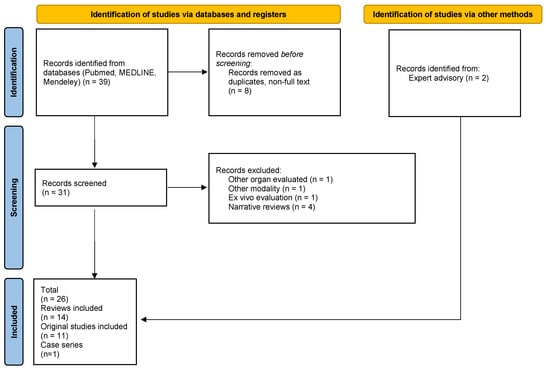

In this paper, we performed a database search (Pubmed, MEDLINE, Mendeley) using combinations of the queries “crohn”, “stricture” and “elastography” up to 19 June 2024 to summarize current knowledge regarding the diagnostic utility of ultrasound (US) and magnetic resonance (MR) elastography techniques in the evaluation of stricturing CD by means of an assessment of the transmural intestinal fibrosis. A total number of 53 articles were found dating back to 2004; however, due to rapid technological progress (reflected by a sudden growth in the number of publications), we decided to include papers published since 1 January 2017 for further evaluation (n = 39). After removal of duplicates and non-full-text publications, a total of 31 records was obtained; 24 were selected for further evaluation after a relevance assessment (1 manuscript was excluded as it concerned methods of liver elastography, 1 for methods of holographic microscopy evaluation, 1 for an ex vivo evaluation of bowel stiffness, and 4 were narrative reviews). These included 12 reviews (2 meta-analysis with systematic reviews, 4 systematic reviews), 11 original scientific papers, and a single case series. Only a single original study concerned MR elastography (Avila 2022) [3]. In addition, we decided to include 2 more recent articles: a meta-analysis and systematic review by Xu et al. (2022) [4] and a systematic review by Lu et al. (2024) [5], as advised by experts.

In each case, we obtained the source publications listed in the review series to critically assess the interpretation of the scientific data; whenever applicable, we decided to address the source publication independently to provide a broader description. Original publications not included in the discussed review series were elaborated separately (n = 4) [6,7,8,9]. For review series including both human and animal models, only data on humans were further evaluated [10] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of manuscript selection [own source].

3. Elastography as a Measure of Transmural Bowel Fibrosis—Current State of Knowledge

3.1. Scientific Evidence from Published Meta-Analyses and Systematic Reviews

In the first meta-analysis on ultrasound elasticity imaging (UEI) in stricturing Crohn’s disease (CD) from 2019 (including scientific papers published before 31 March 2018), Vestito et al. included six studies [10,11,12,13,14,15] with a total of 217 patients with CD, and 231 bowel segments (76 with fibrotic strictures) utilizing either strain (n = 4) or shear wave (n = 2) elastography (presented as a pooled strain ratio, n = 3 or pooled standardized mean strain value, n = 3; expressed in meters per second) as a discriminator between inflammatory and fibrotic strictures in patients with CD. Histological or post-surgery specimens served as a reference for the measurement of the degree of fibrosis. Although the strain values were higher in fibrotic lesions, with a standardized mean difference of 0.85 (95% confidence level [CI]: 0 to 1.71) for the strain ratio and 1.0 (95% CI: −0.11 to 2.10) for the mean standardized strain value, the statistical significance was borderline (p = 0.05 and p = 0.08, respectively). In addition, a high level of heterogeneity was observed between the studies, and nearly all of them (five out of six) were assigned with either high or uncertain risk of bias as evaluated by QUADAS-2 [16].

To no surprise, the results presented in the cited meta-analysis were congruent with the systematic reviews published previously by Pescatori et al. (2018) and Bettenworth et al. (early 2019) [2,17]. Pescatori et al. focused on prospective human studies published between 2008 and 2015, resulting in a total of 129 patients and 154 lesions. Most studies included patients with terminal ileal Crohn’s disease, whereas a single study also allowed for the inclusion of patients with strictures due to other colon pathologies (i.e., adenomas, carcinomas). In six out of seven studies, axial strain elastography was performed, with only a single study utilizing shear wave sonoelastography. Five authors used surgical specimens as a reference, two of them performing US directly on the resected specimens. Authors of the evaluated research used different parameters to assess sonoelastographic data (e.g., absolute strain value, relative strain, semiquantitative scales, ultrasound velocity), aimed at different study endpoints and to some extent presented various approaches for the selection of the examination area, all these reflecting a high level of heterogeneity between the studies. Despite that, all authors managed to find a correlation between the degree of fibrosis and elastography findings, indicating that US elastography can differentiate between inflammatory and fibrotic strictures. Apparently, the wall strain of the fibrotic bowel significantly decreases (both if measured directly, or normalized to external parameters such as unaffected bowel, mesenteric fat and abdominal muscles) [2]. In their systematic review published on behalf of the Stenosis Therapy and Anti-Fibrotic Research (STAR) Consortium, Bettenworth et al. provided a comprehensive definition of CD-related strictures based on an up-to-date research summary on all cross-sectional imaging modalities. One of the main conclusions drawn from the evaluation was a substantial heterogeneity in the definition of stricturing CD used by different authors. Only two studies on US elasticity measurements met the inclusion criteria for the review in terms of separation between inflammatory and fibrotic strictures; both used the strain ratio as a descriptor for stricture characterization and histopathology as a reference [17]. The presented results were contradictory, with Baumgart et al. proving that affected intestinal segments were much less mechanically compliant, with noted strain mean values being significantly higher in unaffected bowel segments (p < 0.001), and these findings corresponded well with both increased muscular content and collagen deposition within the intestinal wall on histopathology, as well as with direct tensiometry [14,18]. On the contrary, Serra et al. showed no significant correlations between the degree of inflammation and fibrosis (strain ratio vs. histopathological score of inflammation, p = 0.531, fibrosis, p = 0.877, clinical/biochemical markers, p values between 0.485 for C-reactive protein and up to 0.965 for previous anti-TNF therapy) [13].

In the second half of 2021, two more systematic reviews were published, although this time not limited solely to fibrotic strictures but addressing the feasibility of sonoelastography in the assessment of different types of lesions over the course of IBD.

Ślósarz et al. focused on multiple techniques, including strain (SE) and shear-wave elastography (SWE) and acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI; otherwise known as point SWE) in IBD, not limiting the study solely to Crohn’s disease. The investigated source data sets were published between 2015 and mid-2021; 12 full-text publications were included in the review (only 1 concerned ulcerative colitis) [19]. Of particular interest were the results presented by Fraquelli et al., who compared the discriminatory value of sonoelastography in the assessment of both inflammatory and fibrotic content of intestinal lesions; the authors found that the strain ratio had an excellent discriminatory ability for diagnosing severe bowel fibrosis, as assessed by the AUROC (strain ratio: 0.917; 95% CI, 0.788–1.000); in addition, a correlation was proved between the wall thickness on conventional US and strain ratios [11,19]. Fufezan et al. established a correlation not only between US strain ratio and the degree of fibrosis but also disease activity markers (but not fecal calprotectin) [19,20]. A whole new chapter started with the era of sonoelastography represented by new quantitative methods—SWE and ARFI. Although Lu et al. (2017) observed higher SWE mean values in patients who required surgical treatment due to stricturing disease compared to those treated conservatively (p < 0.01), they failed to find a correlation between SWE values and fibrosis in histopathology samples obtained from 15 surgical patients [14,19]. Chen et al. (2018) struggled to grade fibrosis based on SWE measurements, dividing lesions into mild, moderate and severe according to preset cut-off value ranges in kPa [21]. The authors reached a sensitivity of 69.6% and specificity of 91.7% (AUC 0.822, p = 0.002) when applying the cut-off value of 22.55 kPa as a discriminator between mild/moderate and severe fibrosis. In addition, when compared to histology, SWE mean values correlated with the degree of fibrosis, irrespective of inflammation [19,21]. Ding et al. made an attempt to compare real-time or strain elastography with ARFI and p-SWE, using histopathology as a reference [22]. With an optimal cut-off value of shear wave velocity set at 2.73 m/s, only p-SWE reached decent thresholds of sensitivity—75%, specificity—100%, diagnostic accuracy—96%, PPV—100% and NPV—95.5% (AUROC, 0.833; p < 0.05) [19,22]. Nonetheless, the major conclusion drawn from the systematic review performed by Ślósarz et al. is that despite promising results indicating sonoelastography as a potential discriminator between the inflammatory and fibrotic strictures, the diversity in technical aspects of measurements between particular elastography techniques (RTE vs. SWE), or even within the same modality but with US systems provided by numerous vendors (measuring slightly different physical properties) hinder direct comparisons and thus translation of the studies into routine clinical practice. This is mainly due to the inability to set the exact cut-off values for significant fibrosis in a uniform manner, using standardized units [19].

Grażyńska et al. evaluated 15 articles from 2011 to 2019 dedicated to the topic of SE and SWE applications in Crohn’s disease only [23]. The authors extracted data from a total 507 patients, 427 evaluated in prospectively designed studies: 2 studies included pediatric patients; 11 assessed strain and 5 shear-wave elastography; and 9 studies used histology as a reference. The majority of the evaluated studies (11 out of 15) overlapped with the analysis performed by Ślósarz et al.; however, data were extracted in a different, more synthetic manner, aiming to compare not only the feasibility of sonoelastography in the characterization of CD strictures but also scientific strategies and methodology (aims/endpoints—detecting fibrosis or inflammation, distinguishing inflammatory and fibrotic strictures, assessing response to anti-TNF treatment, predicting surgery, discriminating between CD and other pathologies; number of investigators; CD activity scales; elastography technique—strain, shear-wave; investigated parameters—qualitative, semi-quantitative, quantitative methods; ROI placement/ reference ROI; source of strain in SE; single vs. multiple measurements at single or multiple time points; units; reference methods—histology/ histopathology or other diagnostic imaging modality) of the source documents. Such an approach enabled them to better depict all the diversity among the studies; not even two of the fifteen studies shared the same methodology [23]. This highlights how important it is to introduce a unified measurement technique (possible guidelines) and parameters (for both strain and shear wave UEI), to prompt further feasibility studies in a clinical setting. Still, only scarce data are available on the only true quantitative modality—SWE. Some authors managed to present a very interesting finding regarding the reproducibility of the elastography measurements; the interobserver agreement in the assessed studies (n = 9), expressed either as subjective measures or Kappa values, was reported as moderate to excellence in the majority of cases [23]. Only Havre et al. reported poor agreeability with Kappa value equal to 0.38, in one of the earliest source articles (2014) included in the review [23,24].

The year 2022 brought a new meta-analysis by Xu et al. dedicated to assessing the eligibility of combined ultrasound techniques including B-mode morphometric parameters, contrast-enhanced ultrasound and sonoelastography. In terms of sonoelastography, the authors based their analysis on publications from the years 2014–2019 [11,13,14,22,25,26]. The source data only overlapped with a previous analysis by Vestito et al. from 2019 to some extent, with pooled data including a slightly larger total number of bowel segments of 248. The meta-analysis was focused on evaluating the performance of SR and SV parameters, which both proved to be significantly associated with fibrotic stenosis [SMD = 1.08; 95% CI: 0.47–1.69; p = 0.000]. The reported heterogeneity within the selected studies was high [I2 = 70.2% and p = 0.003] [3].

Some more recent data (from 2022 and 2023) were included in the reviews by Pruijit et al. [27,28,29] and Lu et al. [30,31,32,33,34]—both published in 2024. Apart from Allocca et al. [31], all authors of the new original series utilized shear wave elastography methods in their studies (SWE, p-SWE, ARFI) [28,29,32,33,34]. Differentiating inflammatory from fibrotic stricturing disease was the main focus of the two studies by Allocca [31] and Zhang [33]. Both studies’ authors used a histology assessment of the resected intestinal segments as a reference. Allocca solely evaluated multiple US parameters (including bowel wall thickness and flow signals on color Doppler) along with SE, leading to the conclusion of no significant correlation between sonoelastography and intestinal fibrosis expressed as either collagen or alpha smooth muscle actinin in the full thickness bowel wall or submucosal layer (see Table 1 and Table 2) [31]. On the other hand, Zhang aimed to verify the joint efficacy of SWE and computed tomography enterography (CTE) in differentiating phenotypes of stricturing CD. A positive correlation was observed between the SWE (Emean) and intestinal fibrosis (r = 0.653, p = 0.000) with a cut-off value for fibrotic lesions set at 21.30 KPa (AUC: 0.877, sensitivity: 88.90%, specificity: 89.50%, 95% CI: 0.755~0.999, p = 0.000). Combining SWE with CTE further improved diagnostic performance and specificity (AUC: 0.918, specificity: 94.70%, 95% CI: 0.806~1.000, p = 0.000) [33]. De Cristofaro et al. decided to verify the relationship between the US echopattern of the stricture with the CD clinical behavior and activity. In the analysis, no significant correlation was established between SWE measurements and echopatterns [29]. Wilkens et al., aiming to compare the in vivo preoperative US bowel assessment with the ex vivo examination of the biomechanical properties of the CD strictures on surgical specimens, failed to establish any relevant correlation between US elastography and biomechanical stiffness (see Table 1 and Table 2) [34]. More promising data came from two experiments by Ueno [28] and Matsumoto [32]. Ueno investigated the role of fibrocytes in CD progression to fibrotic patterns and showed that higher numbers of fibrocytes were observed in predominantly fibrotic disease compared to inflammatory strictures, with increased fibrocyte count being strongly correlated with ARFI (see Table 1 and Table 2) [28]. In the study by Matsumoto et al., shear wave elastography proved to be a promising tool in monitoring treatment effectiveness in the fibrotic stricturing CD phenotype [32].

Table 1.

Evaluated meta-analyses, systematic reviews and reviews and their source publications. Annotations: dark grey—meta analyses, mid-grey—systematic review, light grey—reviews.

Table 2.

Study details and main conclusions from the source publications used in the evaluated reviews, systematic reviews and meta-analyses presented in Table 1. Abbreviations: %EG—% of enhancement gain; ADC—apparent diffusion coefficient; alpha-SMA—alpha smooth muscle actinin; ARFI—acoustic radiation force impulse; AUC—area under curve; AUROC—area under receiver operating curve; CAL—calprotectin; CD—Crohn’s disease; CEUS—contrast-enhanced ultrasound; CI—confidence interval; CRP—C-reactive protein; CT—computed tomography; CTE—computed tomography elastography; DCE-MRE—dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance enterography; DE-MRE—delayed-enhancement magnetic resonance enterography; ESR—estimated sedimentation rate; IFX—infliximab; IUS—intestinal ultrasound; MSV—mean strain value; N/A—not applicable; P—prospective; PE—peak enhancement; p-SWE—point shear wave elastography; R—retrospective; SE—strain elastography; SR—strain ratio; SWE—shear wave elastography; SWV—shear wave velocity; TTP—time to peak; UC—ulcerative colitis; UEI—ultrasound elasticity imaging; US—ultrasound; UST—ustekinumab; VTQ—virtual touch quantification (Siemens ARFI application); VT-IQ—virtual touch-IQ (Siemens ARFI application).

3.2. Recent Scientific Data—Are We Closer to Definite Cut-Off Values?

Table 3 contains cumulative data from recent publications (2023, 2024) that were not yet published in any of the available review series [6,7,8,9]. Abu-Ata compared sonoelastography (SWE, shear wave speed—SWS) against histological and second-harmonic imaging microscopy (SHIM) in a pediatric population with stricturing CD requiring surgical intervention. Although no direct, relevant correlation was established between the degree of fibrosis and stiffness of the bowel stricture or right quadrant strictures, multiple other interesting correlations were observed, including the one between bowel wall stiffness and smooth muscle hypertrophy (for more details see Table 3) [6]. The second study on a pediatric population by Sidhu et al. aimed to assess combined CEUS and SWE performance in differentiating the CD stricture phenotype. Reportedly, SWE failed to correlate with the degree of fibrosis on histology; however, no exact statistical data were provided by the authors in the manuscript [7]. Chen et al. retrospectively analyzed a cohort of 130 adults with primarily non-stricturing non-penetrating CD to determine the utility of SWE in predicting disease progression to a fibrotic phenotype. In the multivariate analysis, SWE proved to be the only independent variable predicting the disease progression at a cutoff of 12.75 kPa (reverse of the HR) [8]. Kapoor et al. decided to include patients with chronic diarrhea and bowel wall thickening stated on IUS (not limiting themselves to CD or IBD patients) to test SWE in discriminating inflammatory from fibrotic strictures, against CE-CT as a reference standard. According to the authors, SWE not only allowed to differentiate between the two disease phenotypes but was also a useful indicator of the possible underlying etiology of the bowel wall thickening [9].

Table 3.

Characteristics of the recent publications not included in the investigated review series. Abbreviations: ARFI—acoustic radiation force impulse; AUROC—area under the receiver operating curve; CD—Crohn’s disease; CEUS—contrast-enhanced ultrasound; CE-CT—contrast-enhanced computed tomography; CI—confidence interval; HR—hazard ratio; IUS—intestinal ultrasound MRE—magnetic resonance enterography; N/A—not applicable; P—prospective; R—retrospective; SBWT—small-bowel wall thickness; SWD—shear wave dispersion; SWE—shear wave elastography; SWV—shear wave velocity; UEI—ultrasound elasticity imaging; US—ultrasound.

3.3. Magnetic Resonance Elastography

The research strategy retrieved only a single original article—a pilot study by Avila et al. on the performance of magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) in detecting fibrotic lesions and predicting course disease in patients with CD [3]. In this prospective study, the authors included 69 adult patients with a CD diagnosis who underwent contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance enterography and were followed for 450 days afterwards to assess for possible future clinical events (defined as abdominal surgery, hospitalization or consultation at emergency department for abdominal pain or digestive occlusion). All the exams were performed on a 1.5 T scanner with a 30-channel body matrix coil and a 32-channel spine matrix coil for signal reception. One liter of mannitol solution was used as an oral contrast for MRE, and 0.5 mg of glucagon was injected intravenously as intestinal motility inhibitor. Elastography was performed prior to contrast injection. The standard pneumatic active driver system and inversion algorithm (Resoundant, Rochester, MN, USA) were utilized with a frequency of the vibration set at 60 Hz. The passive driver was positioned on the anterior abdomen based on the location of the bowel disease on the morphological sequences. A prototype single-breath-hold multi-slice 2D SE-EPI-based sequence with through-slice motion encoding was used to obtain the magnitude of the complex shear modulus of the affected bowel loops—a measure of stiffness. The region of interest (ROI) on stiffness maps was copied during post-processing from the morphological images at the site of the delineated lesion. Mean stiffness values in kPa were then recorded with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The fibrosis score was assessed visually on a 10-point scale (0 to 9) based on DCE-MRE images by an experienced radiology specialist.

The authors found a significant correlation between the stiffness value measured by MR elastography and the degree of fibrosis based on visual assessment on DCE-MRE (p < 0.001). A bowel stiffness ≥ 3.57 kPa predicted the occurrence of clinical events with an area under the curve of 0.82 (95% CI 0.71–0.93; p < 0.0001). Unfortunately, no histology verification was introduced in this study to correlate MR findings with degree of fibrosis.

4. Conclusions and Future Directions

Despite growing collective and original data regarding numerous applications of mostly ultrasound elastography (quantification of fibrosis, distinguishing inflammatory from predominantly fibrotic strictures, assessment of treatment response, predicting disease progression) constantly emerging, to date, we are still lacking any uniformization in both cut-off values and principles of measurements, i.e., reference tissue in strain elastography (mesenteric fat, abdominal muscles, unaffected bowel segment), units, not to mention subtle differences in technical background of SWE techniques utilized by different vendors. It should be emphasized the considerable heterogeneity of study design—including endpoints, verification method (many examinations did not refer to histopathology) and the parameter evaluated—wave velocity, ARFI, etc. (including different technologies used by different ultrasound manufacturers). All these factors imply that ultrasound elastography techniques are hardly translatable throughout different medical centers, practitioners and ultrasound devices, largely depending on the local experience. Only a few of the cited studies clarified the reproducibility of SWE measurements and stated the interobserver agreement [6,7,11,13,14,18,30,34,43,45]. Sidhu et al., Lu et al., Baumart et al. and Lo Re G et al. introduced no direct interobserver agreement, however, in Fraqueli et al.’s article, interobserver agreement was excellent (between two investigators) with an ICC at 0.90 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.75–0.96) [7,11,14,18,45]. Mazza et al. evaluated the interobserver agreement in RTE between the same operators in a previous study of their group, which was excellent (intraclass correlation coefficient 0.78; 95% CI 0.42–0.91) [43]. Nonetheless, the existing medical evidence is promising, especially in terms of possible longitudinal, comparative studies (follow-up) of patients in the course of the disease, which seems to be of particular interest in children (lack of radiation, less invasive contrast media) and terminal ileal disease (easily accessible). Also, combining UEI modalities (strain and shear wave elastography) with techniques enabling the assessment of contrast kinetics (CEUS, DCE- or DE-MRE, CE-CT) substantially increased the diagnostic performance of diagnostic imaging in discriminating between CD phenotypes.

Contrary to ultrasound imaging, magnetic resonance elastography seems to have reached a dead end, especially with emerging applications of magnetization transfer imaging to assess fibrotic strictures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K.; methodology, M.K.; software, M.Z.; validation, M.K.; formal analysis, M.Z.; investigation, M.K.; resources, M.Z. and A.D.-Z.; data curation, A.D.-Z.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K. and M.Z.; writing—review and editing, A.D-Z.; visualization, A.D.-Z.; supervision, A.D.-Z.; project administration, M.Z.; funding acquisition, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Foti, P.V.; Travali, M.; Farina, R.; Palmucci, S.; Coronella, M.; Spatola, C.; Puzzo, L.; Garro, R.; Inserra, G.; Riguccio, G.; et al. Can Conventional and Diffusion-Weighted MR Enterography Biomarkers Differentiate Inflammatory from Fibrotic Strictures in Crohn’s Disease? Medicina 2021, 57, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pescatori, L.C.; Mauri, G.; Savarino, E.; Pastorelli, L.; Vecchi, M.; Sconfienza, L.M. Bowel Sonoelastography in Patients with Crohn’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2018, 44, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avila, F.; Caron, B.; Hossu, G.; Ambarki, K.; Kannengiesser, S.; Odille, F.; Felblinger, J.; Danese, S.; Choukour, M.; Laurent, V.; et al. Magnetic Resonance Elastography for Assessing Fibrosis in Patients with Crohn’s Disease: A Pilot Study. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2022, 67, 4518–4524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Jiang, W.; Wang, L.; Mao, X.; Ye, Z.; Zhang, H. Intestinal Ultrasound for Differentiating Fibrotic or Inflammatory Stenosis in Crohn’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2022, 16, 1493–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.; Merrill, C.; Medellin, A.; Novak, K.; Wilson, S.R. Bowel Ultrasound State of the Art: Grayscale and Doppler Ultrasound, Contrast Enhancement, and Elastography in Crohn Disease. J. Ultrasound Med. 2019, 38, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Ata, N.; Dillman, J.R.; Rubin, J.M.; Collins, M.H.; Johnson, L.A.; Imbus, R.S.; Bonkowski, E.L.; Denson, L.A.; Higgins, P.D.R. Ultrasound Shear Wave Elastography in Pediatric Stricturing Small Bowel Crohn Disease: Correlation with Histology and Second Harmonic Imaging Microscopy. Pediatr. Radiol. 2023, 53, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, S.D.; Joseph, S.; Dunn, E.; Cuffari, C. The Utility of Contrast Enhanced Ultrasound and Elastography in the Early Detection of Fibro-Stenotic Ileal Strictures in Children with Crohn’s Disease. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Nutr. 2023, 26, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-J.; He, J.-S.; Xiong, S.-S.; Li, M.-Y.; Chen, S.-L.; Chen, B.-L.; Qiu, Y.; Xia, Q.-Q.; He, Y.; Zeng, Z.-R.; et al. Bowel Stiffness Assessed by Shear-Wave Ultrasound Elastography Predicts Disease Behavior Progression in Patients With Crohn’s Disease. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2024, 15, e00684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, A.; Singh, A.; Kapur, A.; Mahajan, G.; Sharma, S. Use of Shear Wave Imaging with Intestinal Ultrasonography in Patients with Chronic Diarrhea. J. Clin. Ultrasound 2024, 52, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stidham, R.W.; Xu, J.; Johnson, L.A.; Kim, K.; Moons, D.S.; McKenna, B.J.; Rubin, J.M.; Higgins, P.D.R. Ultrasound Elasticity Imaging for Detecting Intestinal Fibrosis and Inflammation in Rats and Humans With Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 819–826.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraquelli, M.; Branchi, F.; Cribiù, F.M.; Orlando, S.; Casazza, G.; Magarotto, A.; Massironi, S.; Botti, F.; Contessini-Avesani, E.; Conte, D.; et al. The Role of Ultrasound Elasticity Imaging in Predicting Ileal Fibrosis in Crohn’s Disease Patients. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 2605–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stidham, R.; Dillman, J.; Rubin, J.; Higgins, P. P-111 Using Stiffness Imaging of the Intestine to Predict Response to Medical Therapy in Obstructive Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, S44–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, C.; Rizzello, F.; Pratico’, C.; Felicani, C.; Fiorini, E.; Brugnera, R.; Mazzotta, E.; Giunchi, F.; Fiorentino, M.; D’Errico, A.; et al. Real-Time Elastography for the Detection of Fibrotic and Inflammatory Tissue in Patients with Stricturing Crohn’s Disease. J. Ultrasound 2017, 20, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.; Gui, X.; Chen, W.; Fung, T.; Novak, K.; Wilson, S.R. Ultrasound Shear Wave Elastography and Contrast Enhancement: Effective Biomarkers in Crohn’s Disease Strictures. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlova, L.P.; Samsonova, T.V.; Khalif, I. P1018 Strain elastography and differential diagnosis of inflammatory and fibrotic strictures in Crohn’s disease. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2017, 5, A518. [Google Scholar]

- Vestito, A.; Marasco, G.; Maconi, G.; Festi, D.; Bazzoli, F.; Zagari, R.M. Role of Ultrasound Elastography in the Detection of Fibrotic Bowel Strictures in Patients with Crohn’s Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ultraschall Med. 2019, 40, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettenworth, D.; Bokemeyer, A.; Baker, M.; Mao, R.; Parker, C.E.; Nguyen, T.; Ma, C.; Panés, J.; Rimola, J.; Fletcher, J.G.; et al. Assessment of Crohn’s Disease-Associated Small Bowel Strictures and Fibrosis on Cross-Sectional Imaging: A Systematic Review. Gut 2019, 68, 1115–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgart, D.C.; Müller, H.P.; Grittner, U.; Metzke, D.; Fischer, A.; Guckelberger, O.; Pascher, A.; Sack, I.; Vieth, M.; Rudolph, B. US-Based Real-Time Elastography for the Detection of Fibrotic Gut Tissue in Patients with Stricturing Crohn Disease. Radiology 2015, 275, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ślósarz, D.; Poniewierka, E.; Neubauer, K.; Kempiński, R. Ultrasound Elastography in the Assessment of the Intestinal Changes in Inflammatory Bowel Disease—Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fufezan, O.; Asavoaie, C.; Tamas, A.; Farcau, D.; Serban, D. Bowel elastography—A pilot study for developing an elastographic scoring system to evaluate disease activity in pediatric Crohn’s disease. Med. Ultrason. 2015, 17, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chen, Y.; Mao, R.; Md, X.L.; Cao, Q.; Chen, Z.; Liu, B.; Chen, S.; Chen, B.; He, Y.; Zeng, Z.; et al. Real-Time Shear Wave Ultrasound Elastography Differentiates Fibrotic from Inflammatory Strictures in Patients with Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2018, 24, 2183–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, S.; Fang, Y.; Wan, J.; Zhao, C.; Xiang, L.; Liu, H.; Pu, H.; Xu, G.; Zhang, K.; Xu, X.; et al. Usefulness of Strain Elastography, ARFI Imaging, and Point Shear Wave Elastography for the Assessment of Crohn Disease Strictures. J. Ultrasound Med. 2019, 38, 2861–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grażyńska, A.; Kufel, J.; Dudek, A.; Cebula, M. Shear Wave and Strain Elastography in Crohn’s Disease—A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havre, R.; Leh, S.; Gilja, O.; Ødegaard, S.; Waage, J.; Baatrup, G.; Nesje, L. Strain Assessment in Surgically Resected Inflammatory and Neoplastic Bowel Lesions. Ultraschall Med.-Eur. J. Ultrasound 2014, 35, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillman, J.R.; Stidham, R.W.; Higgins, P.D.R.; Moons, D.S.; Johnson, L.A.; Keshavarzi, N.R.; Rubin, J.M. Ultrasound Shear Wave Elastography Helps Discriminate Low-grade From High-grade Bowel Wall Fibrosis in Ex Vivo Human Intestinal Specimens. J. Ultrasound Med. 2014, 33, 2115–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, S.; Fraquelli, M.; Coletta, M.; Branchi, F.; Magarotto, A.; Conti, C.B.; Mazza, S.; Conte, D.; Basilisco, G.; Caprioli, F. Ultrasound Elasticity Imaging Predicts Therapeutic Outcomes of Patients With Crohn’s Disease Treated With Anti-Tumour Necrosis Factor Antibodies. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2018, 12, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruijt, M.J.; De Voogd, F.A.E.; Montazeri, N.S.M.; Van Etten-Jamaludin, F.S.; D’Haens, G.R.; Gecse, K.B. Diagnostic Accuracy of Intestinal Ultrasound in the Detection of Intra-Abdominal Complications in Crohn’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2024, 18, 958–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, A.; Jijon, H.B.; Peng, R.; Sparksman, S.; Mainoli, B.; Filyk, A.; Li, Y.; Wilson, S.; Novak, K.; Panaccione, R.; et al. Association of Circulating Fibrocytes With Fibrostenotic Small Bowel Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2022, 28, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cristofaro, E.; Montesano, L.; Capacchione, C.; Lolli, E.; Biancone, L.; Monteleone, G.; Calabrese, E.; Zorzi, F.T. 04.1 Clinical relevance of ultrasonographic features in Crohn’s disease. Dig. Liver Dis. 2022, 54, S128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Rosentreter, R.; Delisle, M.; White, M.; Parker, C.E.; Premji, Z.; Wilson, S.R.; Baker, M.E.; Bhatnagar, G.; Begun, J.; et al. Systematic Review: Defining, Diagnosing and Monitoring Small Bowel Strictures in Crohn’s Disease on Intestinal Ultrasound. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 59, 928–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allocca, M.; Dal Buono, A.; D’Alessio, S.; Spaggiari, P.; Garlatti, V.; Spinelli, A.; Faita, F.; Danese, S. Relationships Between Intestinal Ultrasound Parameters and Histopathologic Findings in a Prospective Cohort of Patients With Crohn’s Disease Undergoing Surgery. J. Ultrasound Med. 2023, 42, 1717–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, H.; Hata, J.; Imuamura, H.; Yo, S.; Sasahira, M.; Misawa, H.; Oosawa, M.; Handa, O.; Umegami, E.; Shiotani, A. Serial Changes in Intestinal Stenotic Stiffness in Patients with Crohn’s Disease Treated with Biologics: A Pilot Study Using Ultrasound Shear Wave Elastography. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 34, 1006–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Xiao, E.; Liu, M.; Mei, X.; Dai, Y. Retrospective Cohort Study of Shear-Wave Elastography and Computed Tomography Enterography in Crohn’s Disease. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkens, R.; Liao, D.-H.; Gregersen, H.; Glerup, H.; Peters, D.A.; Buchard, C.; Tøttrup, A.; Krogh, K. Biomechanical Properties of Strictures in Crohn’s Disease: Can Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography and Magnetic Resonance Enterography Predict Stiffness? Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimola, J.; Capozzi, N. Differentiation of Fibrotic and Inflammatory Component of Crohn’s Disease-Associated Strictures. Intest. Res. 2020, 18, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allocca, M.; Fiorino, G.; Bonifacio, C.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Danese, S. Noninvasive Multimodal Methods to Differentiate Inflamed vs. Fibrotic Strictures in Patients With Crohn’s Disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 17, 2397–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, H.T.D.; Brito, J.; Magro, F. New Cross-Sectional Imaging in IBD. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2018, 34, 194–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pita, I.; Magro, F. Advanced Imaging Techniques for Small Bowel Crohn’s Disease: What Does the Future Hold? Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2018, 11, 1756283X1875718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branchi, F.; Caprioli, F.; Orlando, S.; Conte, D.; Fraquelli, M. Non-Invasive Evaluation of Intestinal Disorders: The Role of Elastographic Techniques. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, R.; Ribeiro, H.; Maconi, G. Bowel Thickening in Crohn’s Disease: Fibrosis or Inflammation? Diagnostic Ultrasound Imaging Tools. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thimm, M.A.; Cuffari, C.; Garcia, A.; Sidhu, S.; Hwang, M. Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound and Shear Wave Elastography Evaluation of Crohn’s Disease Activity in Three Adolescent Patients. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Nutr. 2019, 22, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goertz, R.S.; Lueke, C.; Wildner, D.; Vitali, F.; Neurath, M.F.; Strobel, D. Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse (ARFI) Elastography of the Bowel Wall as a Possible Marker of Inflammatory Activity in Patients with Crohn’s Disease. Clin. Radiol. 2018, 73, 678.e1–678.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, S.; Conforti, F.S.; Forzenigo, L.V.; Piazza, N.; Bertè, R.; Costantino, A.; Fraquelli, M.; Coletta, M.; Rimola, J.; Vecchi, M.; et al. Agreement between Real-Time Elastography and Delayed Enhancement Magnetic Resonance Enterography on Quantifying Bowel Wall Fibrosis in Crohn’s Disease. Dig. Liver Dis. 2022, 54, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quaia, E.; Gennari, A.G.; Cova, M.A.; van Beek, E.J.R. Differentiation of Inflammatory From Fibrotic Ileal Strictures among Patients with Crohn’s Disease Based on Visual Analysis: Feasibility Study Combining Conventional B-Mode Ultrasound, Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound and Strain Elastography. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2018, 44, 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Re, G.; Picone, D.; Vernuccio, F.; Scopelliti, L.; Di Piazza, A.; Tudisca, C.; Serraino, S.; Privitera, G.; Midiri, F.; Salerno, S.; et al. Comparison of US Strain Elastography and Entero-MRI to Typify the Mesenteric and Bowel Wall Changes during Crohn’s Disease: A Pilot Study. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 4257987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Huang, P.L.; Kang, N.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, M.; Zhang, J.Y.; Cao, X.C.; Dai, X.C. The clinical value of multimodal ultrasound for the evaluation of disease activity and complications in inflammatory bowel disease. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2020, 9, 4146–4155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sconfienza, L.M.; Cavallaro, F.; Colombi, V.; Pastorelli, L.; Tontini, G.; Pescatori, L.; Esseridou, A.; Savarino, E.; Messina, C.; Casale, R.; et al. In-Vivo Axial-Strain Sonoelastography Helps Distinguish Acutely-Inflamed from Fibrotic Terminal Ileum Strictures in Patients with Crohn’s Disease: Preliminary Results. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2016, 42, 855–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezzio, C.; Monteleone, M.; Friedman, A.; Furfaro, F.; Fociani, P.; Sampietro, G.M.; Ardizzone, S.; De Franchis, R.; Maconi, G. P158 Real-Time Strain Elastography Accurately Differentiates between Inflammatory and Fibrotic Strictures in Crohn’s Disease. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2013, 7, S72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Stidham, R.; Dillman, J.; Rubin, J.; Higgins, P. P-156 Shear Wave Velocity Measurement in Bowel Wall Using ARFI Ultrasound for Prediction of Response to Medical Therapy in Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2013, 19, S87–S88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustemovic, N.; Cukovic-Cavka, S.; Brinar, M.; Radić, D.; Opacic, M.; Ostojic, R.; Vucelic, B. A pilot study of transrectal endoscopic ultrasound elastography in inflammatory bowel disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011, 11, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).