Assessing the Utility of Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse in the Evaluation of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease with Severe Obesity or Steatosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

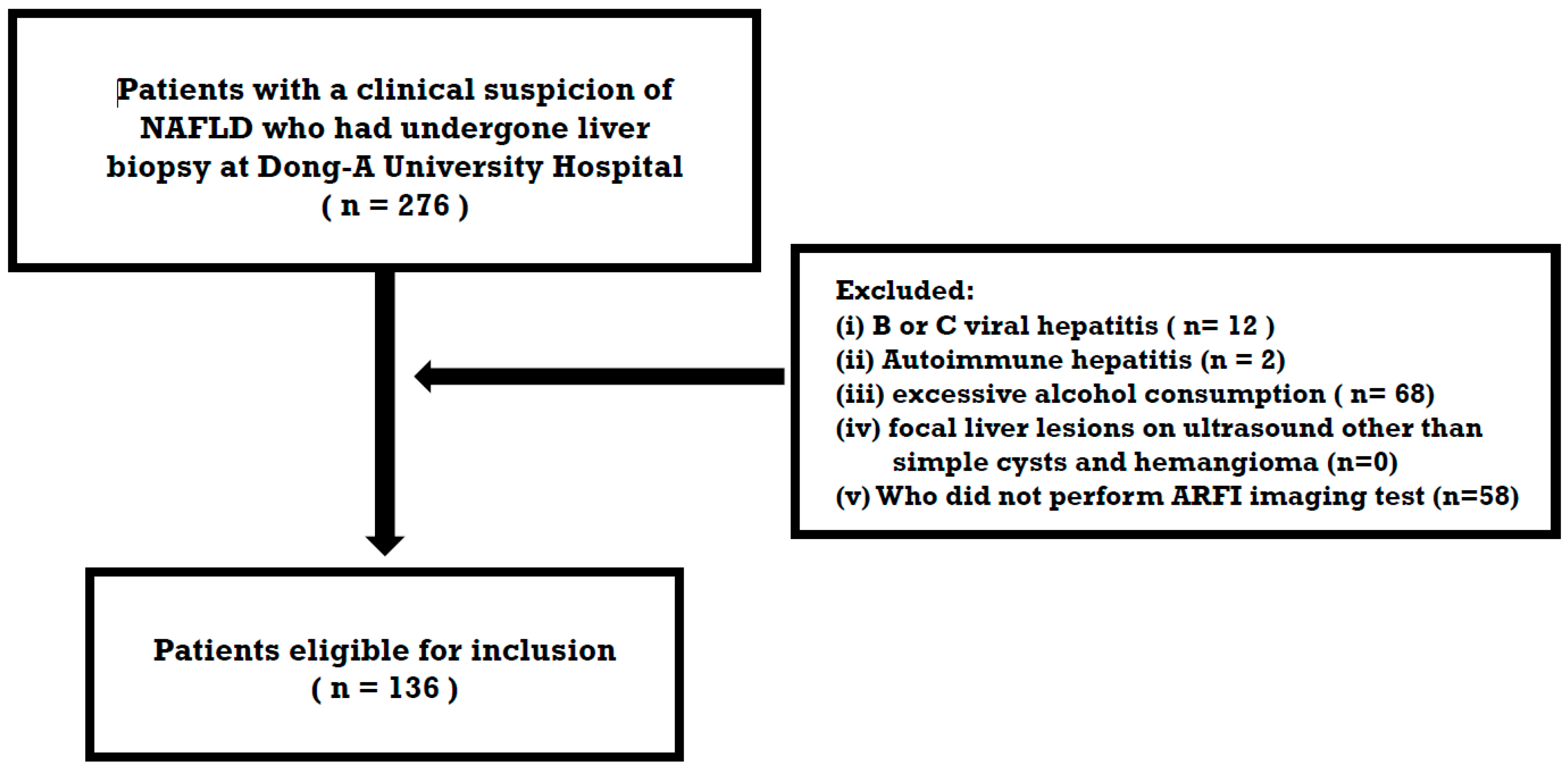

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Serologic Biomarkers for Estimation of Liver Fibrosis

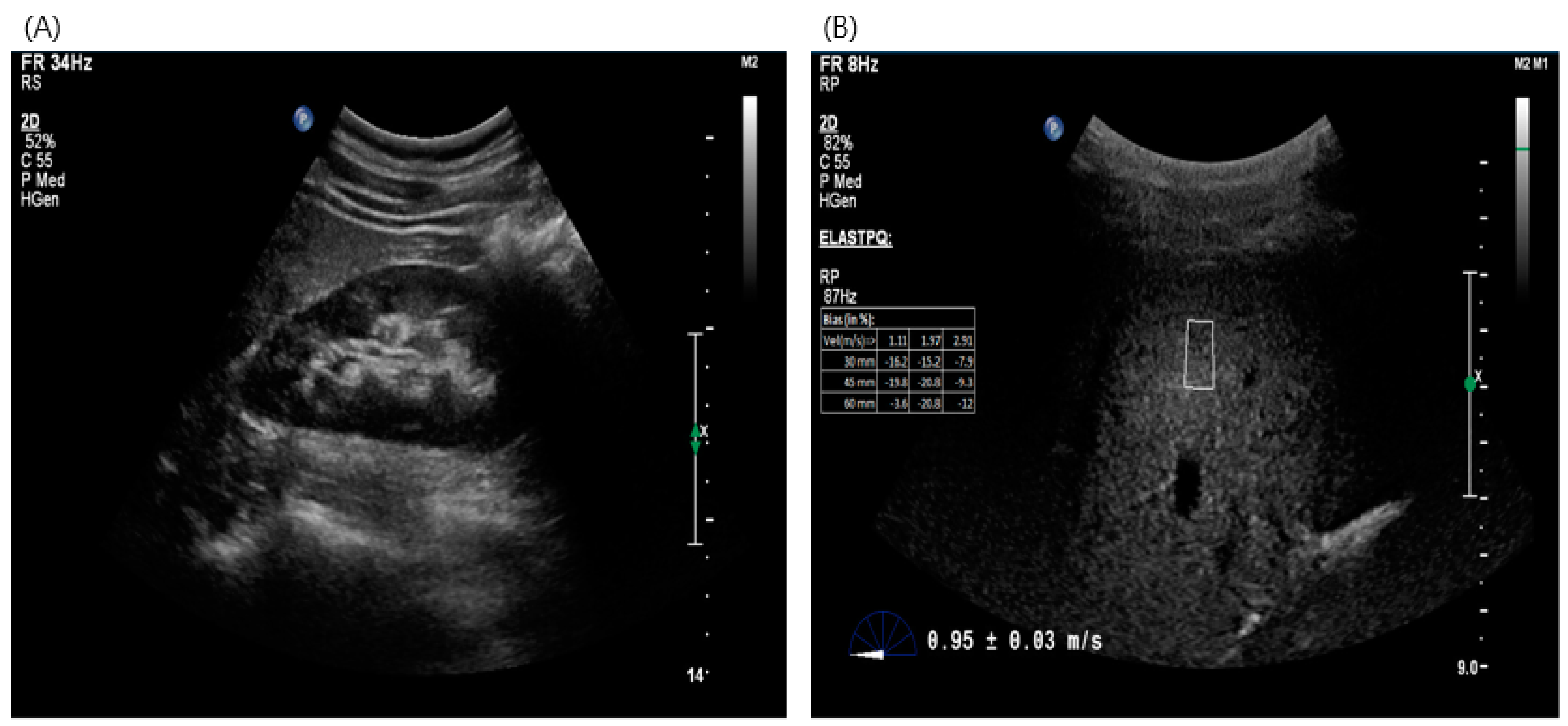

2.3. Imaging Test for Estimation of Liver Fibrosis—Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse (ARFI)

2.4. Liver Histopathology

2.5. Ethics Committee Approval

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline of Clinical and Histopathological Characteristics

3.2. Diagnostic Accuracy of ARFI and Serologic Markers for Advanced Fibrosis

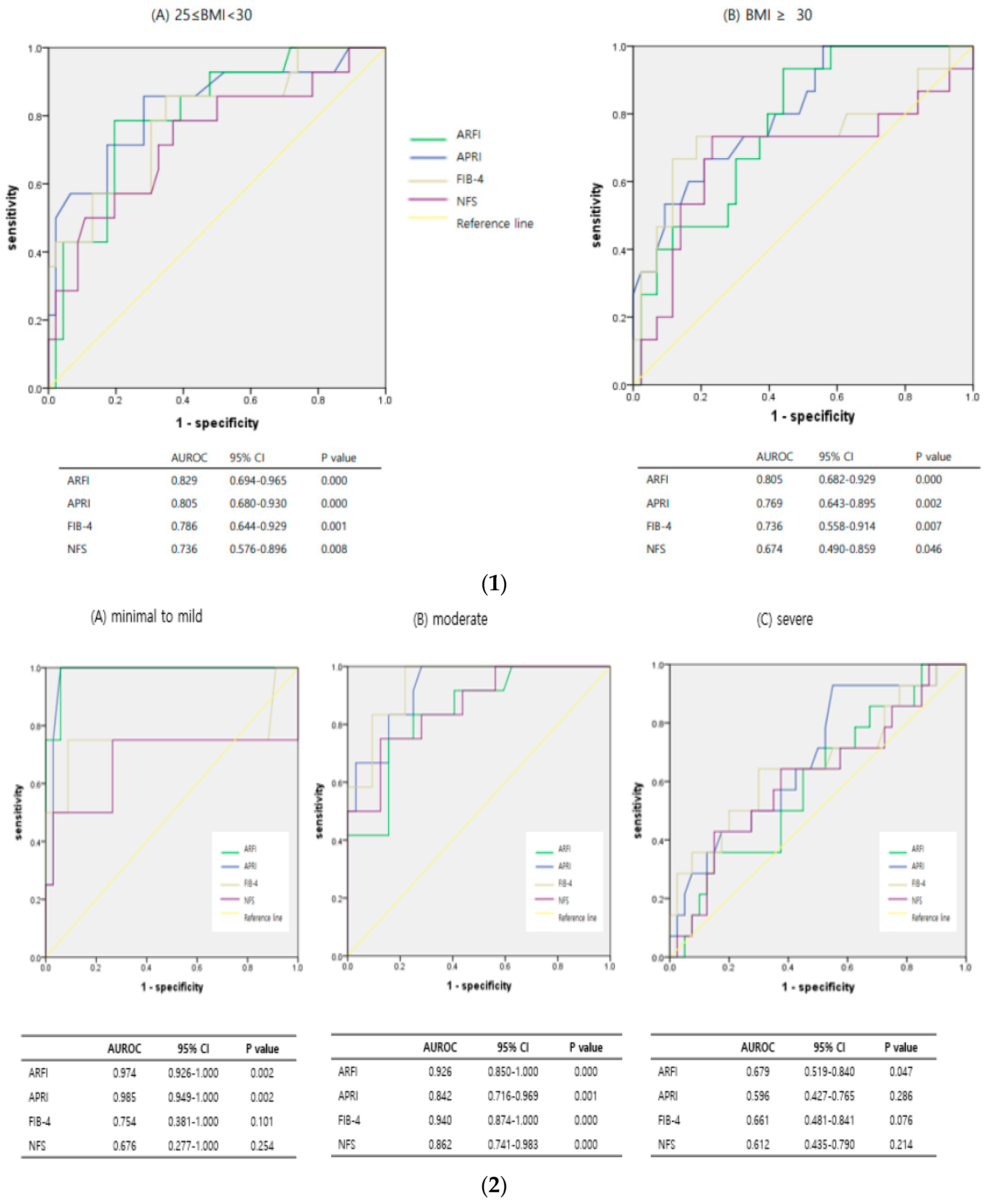

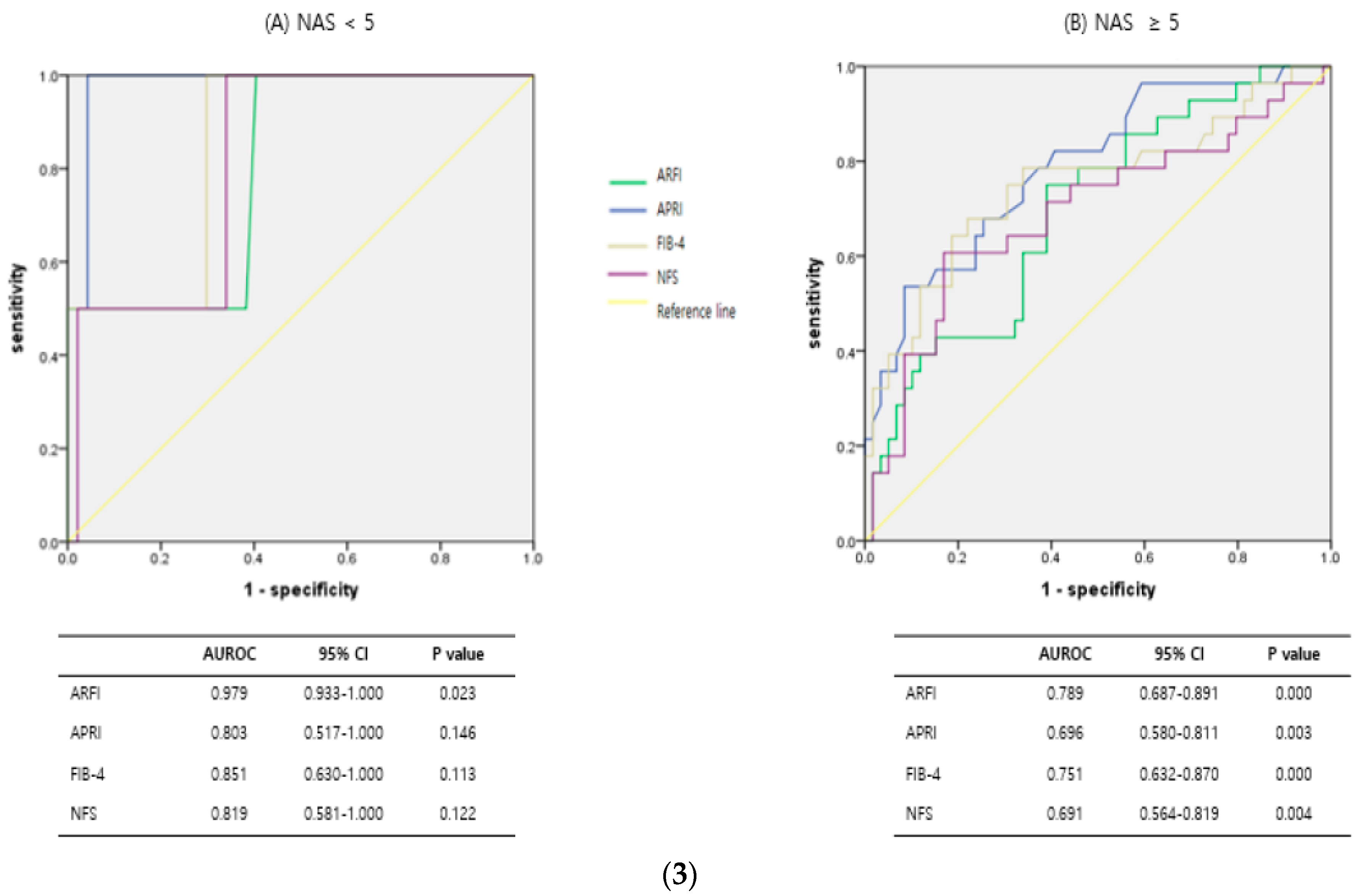

3.3. Diagnostic Predictive Accuracy of ARFI and Serologic Markers According to Subgroups, Such as Obesity, Steatosis, and NASH

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Kang, S.H.; Lee, H.W.; Yoo, J.J.; Cho, Y.; Kim, S.U.; Lee, T.H.; Jang, B.K.; Kim, S.G.; Ahn, S.B.; Kim, H.; et al. KASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2021, 27, 363–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dulai, P.S.; Singh, S.; Patel, J.; Soni, M.; Prokop, L.J.; Younossi, Z.; Sebastiani, G.; Ekstedt, M.; Hagstrom, H.; Nasr, P.; et al. Increased risk of mortality by fibrosis stage in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology 2017, 65, 1557–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, J.; Card, T.R. Reduced mortality rates following elective percutaneous liver biopsies. Gastroenterology 2010, 139, 1230–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terjung, B.; Lemnitzer, I.; Dumoulin, F.L.; Effenberger, W.; Brackmann, H.H.; Sauerbruch, T.; Spengler, U. Bleeding complications after percutaneous liver biopsy. An analysis of risk factors. Digestion 2003, 67, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratziu, V.; Charlotte, F.; Heurtier, A.; Gombert, S.; Giral, P.; Bruckert, E.; Grimaldi, A.; Capron, F.; Poynard, T. Sampling variability of liver biopsy in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 2005, 128, 1898–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, Y.; Jou, J.H. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Recent Guideline Updates. Clin. Liver Dis. 2021, 17, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2016, 64, 1388–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.Y.; Kang, S.M.; Kang, J.H.; Kang, S.Y.; Kim, K.K.; Kim, K.-B.; Kim, B.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, Y.-H.; Kim, J.-H.; et al. 2020 Korean Society for the Study of Obesity Guidelines for the Management of Obesity in Korea. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 2021, 30, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokushige, K.; Ikejima, K.; Ono, M.; Eguchi, Y.; Kamada, Y.; Itoh, Y.; Akuta, N.; Yoneda, M.; Iwasa, M.; Yoneda, M.; et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis 2020. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 56, 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castera, L.; Winnock, M.; Pambrun, E.; Paradis, V.; Perez, P.; Loko, M.; Asselineau, J.; Dabis, F.; Degos, F.; Salmon, D. Comparison of transient elastography (FibroScan), FibroTest, APRI and two algorithms combining these non-invasive tests for liver fibrosis staging in HIV/HCV coinfected patients: ANRS CO13 HEPAVIH and FIBROSTIC collaboration. HIV Med. 2014, 15, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, S.K.; Kim, W.; Kim, D.; Kim, J.H.; Oh, S.; Lee, K.L.; Chang, M.S.; Jung, Y.J.; So, Y.H.; Lee, M.S.; et al. Steatosis severity affects the diagnostic performances of noninvasive fibrosis tests in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 2018, 38, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demir, M.; Lang, S.; Nierhoff, D.; Drebber, U.; Hardt, A.; Wedemeyer, I.; Schulte, S.; Quasdorff, M.; Goeser, T.; Töx, U.; et al. Stepwise combination of simple noninvasive fibrosis scoring systems increases diagnostic accuracy in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2013, 47, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Vali, Y.; Boursier, J.; Spijker, R.; Anstee, Q.M.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Zafarmand, M.H. Prognostic accuracy of FIB-4, NAFLD fibrosis score and APRI for NAFLD-related events: A systematic review. Liver Int. 2021, 41, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilar-Gomez, E.; Chalasani, N. Non-invasive assessment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Clinical prediction rules and blood-based biomarkers. J. Hepatol. 2018, 68, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angulo, P.; Hui, J.M.; Marchesini, G.; Bugianesi, E.; George, J.; Farrell, G.C.; Enders, F.; Saksena, S.; Burt, A.D.; Bida, J.P.; et al. The NAFLD fibrosis score: A noninvasive system that identifies liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. Hepatology 2007, 45, 846–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardi, R.; Airaghi, L.; Targher, G.; Serviddio, G.; Maffi, G.; Mantovani, A.; Maffeis, C.; Colecchia, A.; Villani, R.; Rinaldi, L.; et al. NAFLD fibrosis score (NFS) can be used in outpatient services to identify chronic vascular complications besides advanced liver fibrosis in type 2 diabetes. J. Diabetes Its Complicat. 2020, 34, 107684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, S.M.-T.; Kroh, A.; Ulmer, T.F.; Andruszkow, J.; Luedde, T.; Brozat, J.F.; Neumann, U.P.; Alizai, P.H. Evaluation of NAFLD and fibrosis in obese patients—A comparison of histological and clinical scoring systems. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020, 20, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treeprasertsuk, S.; Björnsson, E.; Enders, F.; Suwanwalaikorn, S.; Lindor, K.D. NAFLD fibrosis score: A prognostic predictor for mortality and liver complications among NAFLD patients. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 1219–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.; Nguyen, V.H.; Tanaka, T.; Park, H.; Yeh, M.-L.; Kawanaka, M.; Arai, T.; Atsukawa, M.; Yoon, E.L.; Tsai, P.-C.; et al. Poor Diagnostic Efficacy of Noninvasive Tests for Advanced Fibrosis in Obese or Younger than 60 Diabetic NAFLD patients. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 21, 1013–1022.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, E.X.; Lee, J.W.; Jumat, N.H.; Chan, W.-K.; Treeprasertsuk, S.; Goh, G.B.-B.; Fan, J.-G.; Song, M.J.; Charatcharoenwitthaya, P.; Duseja, A.; et al. Non-obese non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in Asia: An international registry study. Metabolism 2022, 126, 154911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, V.W.; Vergniol, J.; Wong, G.L.; Foucher, J.; Chan, H.L.-Y.; Le Bail, B.; Choi, P.C.-L.; Kowo, M.; Chan, A.W.-H.; Merrouche, W.; et al. Diagnosis of fibrosis and cirrhosis using liver stiffness measurement in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2010, 51, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, R.P.; Pomier-Layrargues, G.; Kirsch, R.; Pollett, A.; Duarte-Rojo, A.; Wong, D.; Beaton, M.; Levstik, M.; Crotty, P.; Elkashab, M. Feasibility and diagnostic performance of the FibroScan XL probe for liver stiffness measurement in overweight and obese patients. Hepatology 2012, 55, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Onofrio, M.; Crosara, S.; De Robertis, R.; Canestrini, S.; Demozzi, E.; Gallotti, A.; Pozzi Mucelli, R. Acoustic radiation force impulse of the liver. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 4841–4849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich-Rust, M.; Romen, D.; Vermehren, J.; Kriener, S.; Sadet, D.; Herrmann, E.; Zeuzem, S.; Bojunga, J. Acoustic radiation force impulse-imaging and transient elastography for non-invasive assessment of liver fibrosis and steatosis in NAFLD. Eur. J. Radiol. 2012, 81, e325–e331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fierbinteanu Braticevici, C.; Sporea, I.; Panaitescu, E.; Tribus, L. Value of acoustic radiation force impulse imaging elastography for non-invasive evaluation of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2013, 39, 1942–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyysalo, J.; Männistö, V.T.; Zhou, Y.; Arola, J.; Kärjä, V.; Leivonen, M.; Juuti, A.; Jaser, N.; Lallukka, S.; Käkelä, P.; et al. A population-based study on the prevalence of NASH using scores validated against liver histology. J. Hepatol. 2014, 60, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musso, G.; Gambino, R.; Durazzo, M.; Cassader, M. Noninvasive assessment of liver disease severity with liver fat score and CK-18 in NAFLD: Prognostic value of liver fat equation goes beyond hepatic fat estimation. Hepatology 2010, 51, 715–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlacchio, A.; Bolacchi, F.; Antonicoli, M.; Coco, I.; Costanzo, E.; Tosti, D.; Francioso, S.; Angelico, M.; Simonetti, G. Liver Elasticity in NASH Patients Evaluated with Real-Time Elastography (RTE). Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2012, 38, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total (n = 136) | ||

| Demographic | ||

| Age at biopsy, y, mean ± SD | 44.92 (±14.34) | |

| Male, n (%) | 71 (52.2%) | |

| Female, n (%) | 65 (47.8%) | |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 29.83 (±4.38) | |

| BMI ≥ 30 | 58 (42.6%) | |

| Impaired fasting glucose, n (%) | 45 (33.1%) | |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 48 (35.3%) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 76 (55.9%) | |

| Biochemical profile (mean, (min, max)) | ||

| AST, U/L | 59.92, (14, 345) | |

| ALT, U/L | 78.17, (9, 451) | |

| Platelet count, 103/uL | 257.17, (114–642) | |

| Albumin, g/dL | 4.47, (3.2–5.3) | |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 123.15, (68–333) | |

| Histology | ||

| Steatosis, n (%) | 0 | 5 (3.7%) |

| 1 | 33 (24.3%) | |

| 2 | 44 (32.4%) | |

| 3 | 54 (39.7%) | |

| Lobular inflammation, n (%) | 0 | 22 (16.2%) |

| 1 | 31 (22.8%) | |

| 2 | 50 (36.8%) | |

| 3 | 33 (24.3%) | |

| Ballooning, n (%) | 0 | 45 (33.1%) |

| 1 | 55 (40.4%) | |

| 2 | 36 (26.5%) | |

| Fibrosis, n (%) | 0 | 49 (36.0%) |

| 1 | 43 (31.6%) | |

| 2 | 14 (10.3%) | |

| 3 | 23 (16.9%) | |

| 4 | 7 (5.1%) | |

| NAFLD activity score, n (%) | not NASH (NAS ≤ 2) | 30 (22.1%) |

| Borderline NASH | 19 (14.0%) | |

| Definite NASH (NAS ≥ 5) | 87 (63.9%) | |

| AUROC (95% CI) | Cut Off | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARFI | 0.832 | >1.32 | 70.0 | 80.19 | 50.0 | 90.4 | 0.000 |

| (0.751–0.914) | |||||||

| APRI | 0.794 | >0.637 | 73.3 | 76.4 | 46.8 | 91.0 | 0.000 |

| (0.711–0.878) | |||||||

| FIB-4 | 0.767 | >1.75 | 63.3 | 85.9 | 55.9 | 89.2 | 0.000 |

| (0.656–0.877) | |||||||

| NFS | 0.696 | >−0.3 | 60.0 | 82.1 | 48.6 | 87.9 | 0.001 |

| (0.579–0.814) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kang, Y.W.; Baek, Y.H.; Lee, J.H.; Roh, Y.H.; Kwon, H.J.; Moon, S.Y.; Son, M.K.; Jeong, J.S. Assessing the Utility of Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse in the Evaluation of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease with Severe Obesity or Steatosis. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1083. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14111083

Kang YW, Baek YH, Lee JH, Roh YH, Kwon HJ, Moon SY, Son MK, Jeong JS. Assessing the Utility of Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse in the Evaluation of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease with Severe Obesity or Steatosis. Diagnostics. 2024; 14(11):1083. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14111083

Chicago/Turabian StyleKang, Yeo Wool, Yang Hyun Baek, Jong Hoon Lee, Young Hoon Roh, Hee Jin Kwon, Sang Yi Moon, Min Kook Son, and Jin Sook Jeong. 2024. "Assessing the Utility of Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse in the Evaluation of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease with Severe Obesity or Steatosis" Diagnostics 14, no. 11: 1083. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14111083

APA StyleKang, Y. W., Baek, Y. H., Lee, J. H., Roh, Y. H., Kwon, H. J., Moon, S. Y., Son, M. K., & Jeong, J. S. (2024). Assessing the Utility of Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse in the Evaluation of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease with Severe Obesity or Steatosis. Diagnostics, 14(11), 1083. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14111083