Combined Merkel Cell Carcinoma with Nodal Presentation: Report of a Case Diagnosed with Excisional but Not Incisional Biopsy and Literature Review

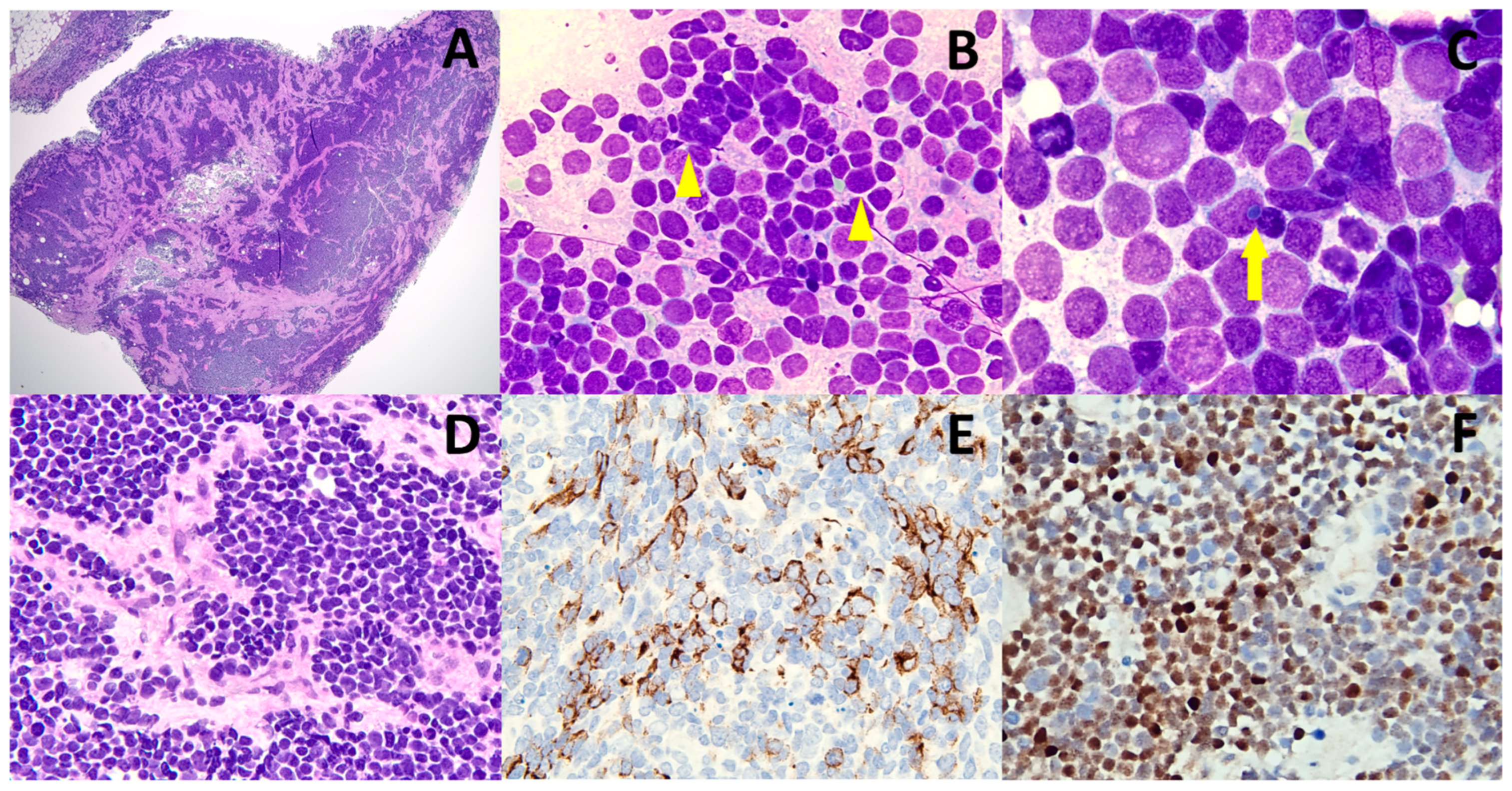

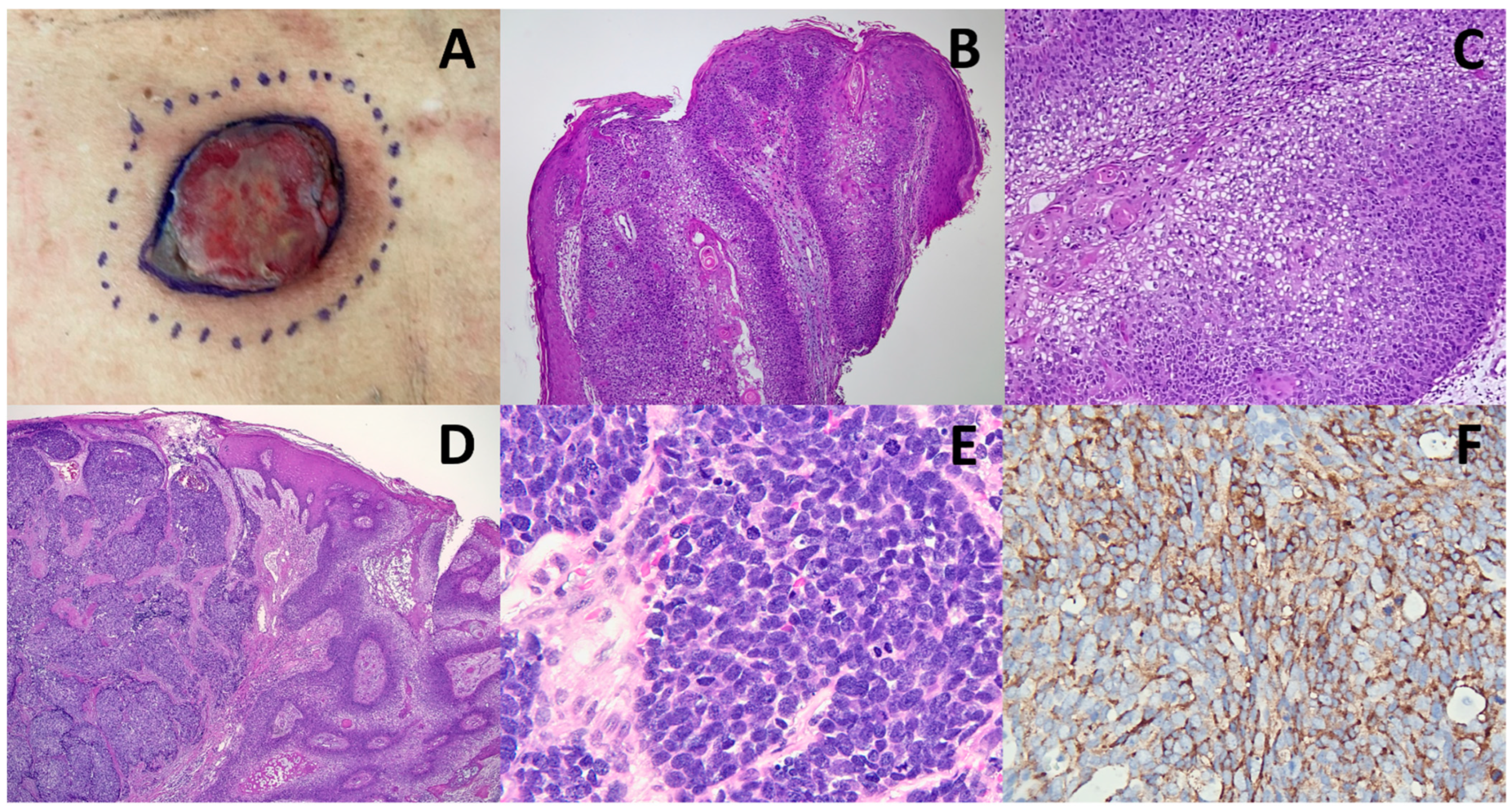

Abstract

1. Background

2. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rotondo, J.C.; Bononi, I.; Puozzo, A.; Govoni, M.; Foschi, V.; Lanza, G.; Gafa, R.; Gaboriaud, P.; Touze, F.A.; Selvatici, R.; et al. Merkel Cell Carcinomas Arising in Autoimmune Disease Affected Patients Treated with Biologic Drugs, Including Anti-TNF. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 3929–3934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, J.C.; Stang, A.; DeCaprio, J.A.; Cerroni, L.; Lebbe, C.; Veness, M.; Nghiem, P. Merkel cell carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauci, M.L.; Aristei, C.; Becker, J.C.; Blom, A.; Bataille, V.; Dreno, B.; Del Marmol, V.; Forsea, A.M.; Fargnoli, M.C.; Grob, J.J.; et al. Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline—Update 2022. Eur. J. Cancer 2022, 171, 203–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, M.P.; Hardee, M.E.; Cornelius, L.A.; Hutchins, L.F.; Becker, J.C.; Gao, L. Merkel Cell Carcinoma: Epidemiology, Target, and Therapy. Curr. Dermatol. Rep. 2014, 3, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, A.; Fabbrocini, G.; Costa, C.; Carmela Annunziata, M.; Scalvenzi, M. Merkel Cell Carcinoma: Therapeutic Update and Emerging Therapies. Dermatol. Ther. 2019, 9, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitskell, K.; Nassar, S.; Ibrahim, H. Merkel cell carcinoma with divergent differentiation. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2020, 45, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B.; Poblet, E.; Rios, J.J.; Kazakov, D.; Kutzner, H.; Brenn, T.; Calonje, E. Merkel cell carcinoma with divergent differentiation: Histopathological and immunohistochemical study of 15 cases with PCR analysis for Merkel cell polyomavirus. Histopathology 2013, 62, 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Viñuela, E.; Traves, V.; Cruz, J.; Machado, I.; López-Guerrero, J.A.; Requena, C.; Llombart, B. Combined Merkel Cell Carcinoma and Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma with Lymph Node metastases: Report of Two Cases. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, A.L.; Louis, P.; Kitts, J.; Busam, K.; Myskowski, P.L.; Wong, R.J.; Chen, C.S.; Spencer, P.; Lacouture, M.; Pulitzer, M.P. Clinical and dermoscopic features of combined cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)/neuroendocrine [Merkel cell] carcinoma (MCC). J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2015, 73, 968–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCoste, R.C.; Walsh, N.M.; Gaston, D.; Ly, T.Y.; Pasternak, S.; Cutler, S.; Nightingale, M.; Carter, M.D. RB1-deficient squamous cell carcinoma: The proposed source of combined Merkel cell carcinoma. Mod. Pathol. 2022, 35, 1829–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.Y.; Lai, F.J.; Chang, S.T.; Chuang, S.S. Diagnostic clues for differentiating Merkel cell carcinoma from lymphoma in fine-needle aspiration cytology. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2022, 50, e23–e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, K.Y. The Origins of Merkel Cell Carcinoma: Defining Paths to the Neuroendocrine Phenotype. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 142, 507–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq Baba, P.U.; Rasool, Z.; Younas Khan, I.; Cockerell, C.J.; Wang, R.; Kassir, M.; Stege, H.; Grabbe, S.; Goldust, M. Merkel Cell Carcinoma: From Pathobiology to Clinical Management. Biology 2021, 10, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.W.; Chang, S.T.; Ho, C.H.; Wang, J.S.; Wang, R.C.; Takeuchi, K.; Chuang, S.S. Merkel cell carcinoma in Taiwan: A rare tumour with a better prognosis in those harbouring Merkel cell polyomavirus. Malays. J. Pathol. 2022, 44, 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kervarrec, T.; Appenzeller, S.; Samimi, M.; Sarma, B.; Sarosi, E.M.; Berthon, P.; Le Corre, Y.; Hainaut-Wierzbicka, E.; Blom, A.; Benethon, N.; et al. Merkel Cell Polyomavirus-Negative Merkel Cell Carcinoma Originating from In Situ Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Keratinocytic Tumor with Neuroendocrine Differentiation. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 142, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobbs, M.M.; Geers, T.E.; Brown, T.S.; Malone, J.C. Triple collision tumor comprising Merkel cell carcinoma with an unusual immunophenotype, squamous cell carcinoma in situ, and basal cell carcinoma. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2020, 47, 764–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suaiti, L.; Onajin, O.; Sangueza, O. Concurrent Metastatic Merkel Cell Carcinoma and Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma in the Same Lymph Node. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2019, 41, e61–e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, J.; Gugelmeier, N.; Mazzei, M.E.; González, S.; Barcia, J.J.; Magliano, J. Lymph Node Metastasis With Both Components of Combined Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma/Merkel Cell (Neuroendocrine) Carcinoma. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2018, 40, 626–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, T.C.; Tsai, K.B.; Wu, C.Y.; Hong, C.H.; Lee, C.H. Presence of the Merkel cell polyomavirus in Merkel cell carcinoma combined with squamous cell carcinoma in a patient with chronic arsenism. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2016, 41, 902–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansai, S.; Noro, S.; Ogita, A.; Fukumoto, H.; Katano, H.; Kawana, S. Case of Merkel cell carcinoma with squamous cell carcinoma possibly arising in chronic radiodermatitis of the hand. J. Dermatol. 2015, 42, 207–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.H.; Alanen, K.; Dabbs, K.D.; Danyluk, J.; Silverman, S. Merkel cell carcinoma with squamous and sarcomatous differentiation. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2008, 35, 955–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Case | Sex | Age | Location of Primary Skin Tumor | Pathology of Skin Tumor | Site of Metastatic Node | Pathology of Metastatic Node | Follow-Up (m) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 94 | M | Left upper arm | Triple collision tumor composed of MCC, SCC and sarcoma | Left axillary | MCC and sarcoma | N/A | Hwang, J.H. et al. (2008) [21] |

| 2 | 88 | F | Cheek | MCC and invasive SCC | Submandibular | Metastatic SCC | DOD (6) | Martin, B. et al. (2013) [7] |

| 3 | 78 | M | Preauricular | MCC and invasive SCC | Cervical | MCC and SCC | N/A | Martin, B. et al. (2013) [7] |

| 4 | 79 | M | Right temple | Triple collision tumor composed of MCC, SCC and sarcoma | Right parotid and postauricular | MCC and SCC | DOD (2) | Martin, B. et al. (2013) [7] |

| 5 | N/A | N/A | N/A | MCC and porocarcinoma | Unspecified | MCC and porocarcinoma | N/A | Martin, B. et al. (2013) [7] |

| 6 | 80 | M | Right middle finger | MCC and invasive SCC | Right axillary | MCC | DOD (5) | Ansai, S. et al. (2015) [20] |

| 7 | 77 | F | Right breast | MCC and invasive SCC | Right axillary | MCC | N/A | Chou, T. C. et al. (2016) [19] |

| 8 | 49 | M | Right forearm | MCC and invasive SCC | Right axillary | MCC and SCC | DOD (N/A) | Navarrete, J. et al. (2018) [18] |

| 9 | 51 | M | Left ear | MCC and invasive SCC | Left retropharyngeal and deep parotid | MCC and SCC | N/A | Suaiti, L. et al. (2019) [17] |

| 10 | 66 | M | Right anterior shoulder | Triple collision tumor composed of MCC, BCC and SCC in situ | Right axillary | MCC | N/A | Hobbs, M.M. et al. (2020) [16] |

| 11 | 83 | M | Right leg | MCC and invasive SCC | Left inguinal | MCC and SCC | DOD (<12) | Ríos-Viñuela, E. et al. (2022) [8] |

| 12 | 78 | M | Neck | MCC and invasive SCC | Cervical | MCC and SCC | DOD (12) | Ríos-Viñuela, E. et al. (2022) [8] |

| 13 | 79 | M | Lower back | MCC and invasive SCC | Left inguinal | MCC | DOD (2) | Current case |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, C.-Y.; Kang, N.-W.; Takeuchi, K.; Chuang, S.-S. Combined Merkel Cell Carcinoma with Nodal Presentation: Report of a Case Diagnosed with Excisional but Not Incisional Biopsy and Literature Review. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 449. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13030449

Liu C-Y, Kang N-W, Takeuchi K, Chuang S-S. Combined Merkel Cell Carcinoma with Nodal Presentation: Report of a Case Diagnosed with Excisional but Not Incisional Biopsy and Literature Review. Diagnostics. 2023; 13(3):449. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13030449

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Chih-Yi, Nai-Wen Kang, Kengo Takeuchi, and Shih-Sung Chuang. 2023. "Combined Merkel Cell Carcinoma with Nodal Presentation: Report of a Case Diagnosed with Excisional but Not Incisional Biopsy and Literature Review" Diagnostics 13, no. 3: 449. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13030449

APA StyleLiu, C.-Y., Kang, N.-W., Takeuchi, K., & Chuang, S.-S. (2023). Combined Merkel Cell Carcinoma with Nodal Presentation: Report of a Case Diagnosed with Excisional but Not Incisional Biopsy and Literature Review. Diagnostics, 13(3), 449. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13030449