Copper Deficiency as Wilson’s Disease Overtreatment: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

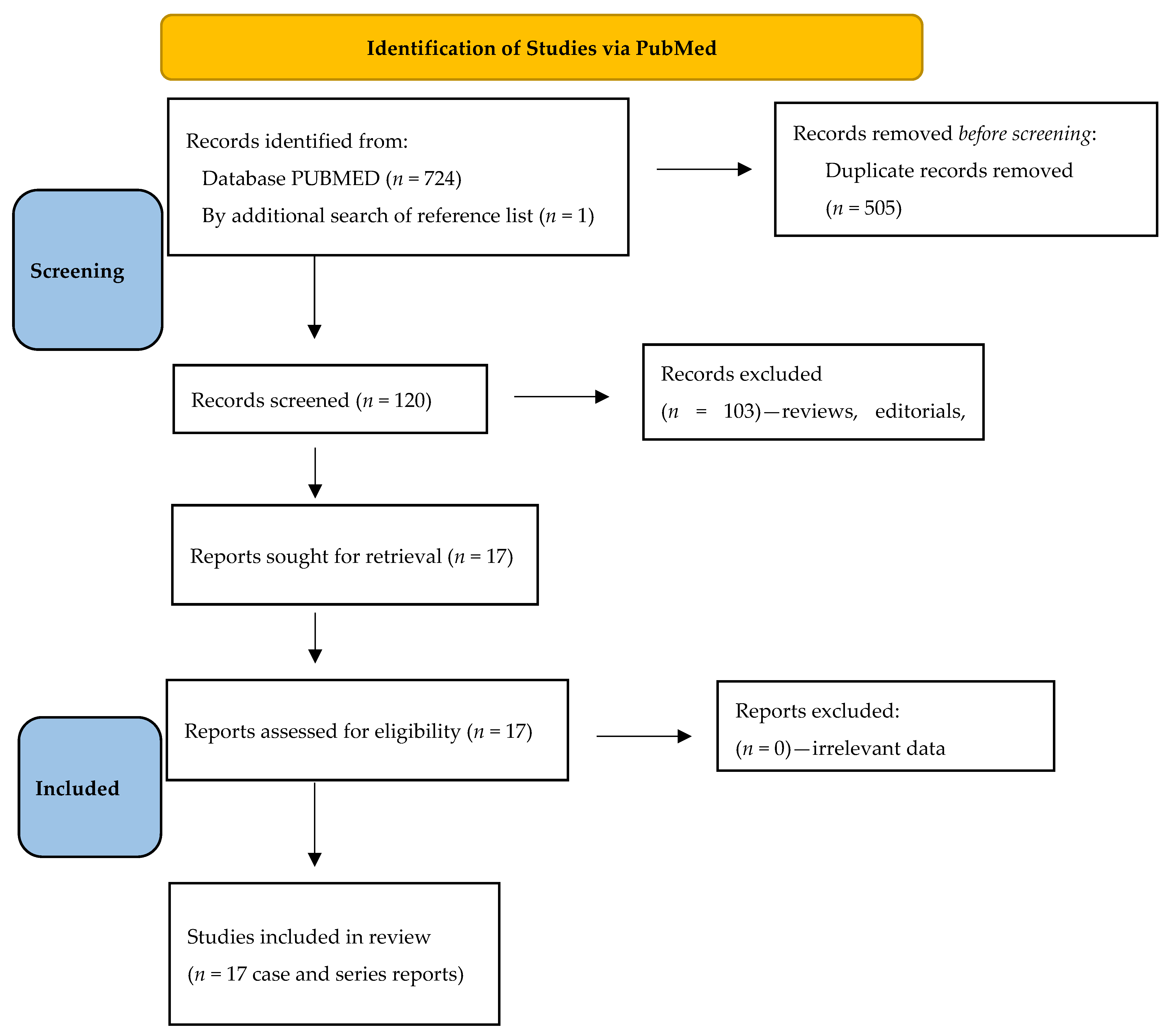

2. Methods

2.1. Literature Search and Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Wilson’s disease. J. Hepatol. 2012, 56, 671–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schilsky, M.L.; Roberts, E.A.; Bronstein, J.M.; Dhawan, A.; Hamilton, J.P.; Rivard, A.M.; Washington, M.K.; Weiss, K.H.; Zimbrean, P.C. A multidisciplinary approach to the diagnosis and management of Wilson disease: Executive summary of the 2022 Practice Guidance on Wilson disease from the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease. Hepatology 2023, 77, 1428–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czlonkowska, A.; Litwin, T. Wilson disease—Currently used anticopper therapy. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2017, 142, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gromadzka, G.; Grycan, M.; Przybyłkowski, A. Monitoring of copper in Wilson disease. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antos, A.; Członkowska, A.; Bembenek, J.; Skowrońska, M.; Kurkowska-Jastrzębska, I.; Litwin, T. Blood based biomarkers of central nervous system involvement in Wilson’s disease. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beinhardt, S.; Leiss, W.; Stattermayer, A.F.; Graziadei, I.; Zoller, H.; Stauber, R.; Maieron, A.; Datz, C.; Steindl-Munda, P.; Hofer, H.; et al. Long-term outcomes of patients with Wilson disease in a large Austrian cohort. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 12, 683–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, G.J.; Askari, F.; Lorincz, M.T.; Carlson, M.; Schilsky, M.; Kluin, K.J.; Hedera, P.; Moretti, P.; Fink, J.K.; Tankanow, R.; et al. Treatment of Wilson disease with ammonium tetrathiomolybdate IV. Comparison of tetrathiomolybdate and trientine in a double-blind study of treatment of the neurologic presentation of Wilson disease. Arch. Neurol. 2006, 63, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Członkowska, A.; Litwin, T.; Dusek, P.; Ferenci, P.; Lutsenko, S.; Medici, V.; Rybakowski, J.K.; Weiss, K.H.; Schilsky, M.L. Wilson disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, K.H.; Askari, F.K.; Członkowska, A.; Ferenci, P.; Bronstein, J.M.; Bega, D.; Bega, D.; Ala, A.; Nicholl, D.; Flint, S.; et al. Bis-choline tetrathiomolybdate in patients with Wilson’s disease: An open label, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 2, 869–876. [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Hamer, C.J.A.; Hoogenraad, T.U. Copper deficiency in Wilson’s disease. Lancet 1989, 334, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, S.; Kaveer, N. CNS demyelination due to hypocupremia in Wilson′s disease from overzealous treatment. Neurol. India 2006, 54, 110–111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Foubert-Samier, A.; Kazadi, A.; Rouanet, M.; Vital, A.; Lagueny, A.; Tison, F.; Meissner, W. Axonal sensory motor neuropathy in copperdeficient Wilson’s disease: Neuropathy in WD. Muscle Nerve 2009, 40, 294–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvath, J.; Beris, P.; Giostra, E.; Martin, P.-Y.; Burkhard, P.R. Zinc-induced copper deficiency in Wilson disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2010, 81, 1410–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benbir, G.; Gunduz, A.; Ertan, S.; Ozkara, C. Partial status epilepticus induced by hypocupremia in a patient with Wilson’s disease. Seizure 2010, 19, 602–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortese, A.; Zangaglia, R.; Lozza, A.; Piccolo, G.; Pacchetti, C. Copper deficiency in Wilson’s disease: Peripheral neuropathy and myelodysplastic syndrome complicating zinc treatment. Mov. Disord. 2011, 26, 1361–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva-Junior, F.P.; Machado, A.A.C.; Lucato, L.T.; Cancado, E.L.R.; Barbosa, E.R. Copper deficiency myeloneuropathy in a patient with Wilson disease. Neurology 2011, 76, 1673–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano Herrero, J.; Muñoz Bertrán, E.; Ortega González, I.; Gómez Espín, R.; López Espín, M.I. Myelopathy secondary to copper deficiency as a complication of treatment of Wilson’s disease. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 35, 704–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodoro, T.; Neutel, D.; Lobo, P.; Geraldo, A.F.; Conceição, I.; Rosa, M.M.; Albuquerque, L.; Ferreira, J.J. Recovery after copper-deficiency myeloneuropathy in Wilson’s disease. J. Neurol. 2013, 260, 1917–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzieżyc, K.; Litwin, T.; Sobańska, A.; Członkowska, A. Symptomatic copper deficiency in three Wilson’s disease patients treated with zinc sulphate. Neurol. Neurochir. Pol. 2014, 48, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.M.; Ekladious, A.; Wheeler, L.; Mohamad, A.A. Wilson disease: Copper deficiency and iatrogenic neurological complications with zinc therapy. Intern. Med. J. 2020, 50, 121–123. [Google Scholar]

- Rau, A.R.; Usha, M.; Mallya, P.; Rau, A.T.K. Cytopenia and bone marrow dysplasia in a case of Wilson’s disease. Indian J. Hematol. Blood Transfus. 2014, 30, 433–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, M.; Johnston, A.; Maclaine Cross, A.; Sharma, A. Reversible pancytopenia caused by severe copper deficiency in a patient with Wilson disease. Med. J. Aust. 2018, 209, 11–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, S.; Gong, J.-Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, J.-S. Anemia following zinc treatment for Wilson’s disease: A case report and literature review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019, 19, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueda, M.; Katsuse, K.; Kakumoto, T.; Kobayashi, S.; Ishiura, H.; Mitsui, J.; Toda, T. Copper deficiency in Wilson’s disease with a normal zinc value. Intern. Med. 2023, 62, 1073–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiser, S.R.; Winston, G.P. Copper deficiency myelopathy. J. Neurol. 2010, 257, 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.S.; Brewer, G.J.; Schoomaker, E.B.; Rabbani, P. Hypocupremia induced by zinc therapy in adults. JAMA 1978, 240, 2166–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Gross, J.B.; Ahlskog, J.E. Copper deficiency myelopathy produces a clinical picture like subacute combined degeneration. Neurology 2004, 63, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaleagasi, H.; Oksuz, N.; Ozal, S.; Yilmaz, A.; Dogu, O. Increased seizure frequency due to copper deficiency in Wilson’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 2013, 333, e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunajeewa, H.; Wall, A.; Metz, J.; Grigg, A. Cytopenias secondary to copper depletion complicating ammonium tetrathiomolybdate therapy for Wilson’s disease. Aust. New Zealand J. Med. 1998, 28, 215–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, A.; Talwar, D.; Morrison, I. The predictive value of low plasma copper and high plasma zinc in detecting zinc-induced copper deficiency. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2016, 53, 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchino, K.; Vu Quang, L.; Enomoto, M.; Nakano, Y.; Yamada, S.; Matsumura, S.; Kanasugi, J.; Takasugi, S.; Nakamura, A.; Horio, T.; et al. Cytopenia associated with copper deficiency. EJHaem 2021, 2, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, W65–W94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linn, H.H.F.; Houwen, R.H.J.; van Hattum, J.; van der Kleij, S.; van Erpecum, K.J. Long-term exclusive zinc monotherapy in symptomatic Wilson disease: Experience in 17 patients. Hepatology 2009, 50, 1442–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ervehjem, C.A.; Sherman, W.C. The action of copper in iron metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 1932, 98, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemssen, T.; Akgun, K.; Członkowska, A.; Antos, A.; Bembenek, J.; Kurkowska-Jastrzębska, I.; Przybyłkowski, A.; Skowrońska, M.; Smolinski, L.; Litwin, T. Serum neurofilament light chain as a biomarker of brain injury in Wilson’s disease: Clinical and neuroradiological correlations. Mov. Disord. 2022, 37, 1074–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemssen, T.; Smolinski, L.; Czlonkowska, A.; Akgun, K.; Antos, A.; Bembenek, J.; Kurkowska-Jastrzębska, I.; Przybyłkowski, A.; Skowrońska, M.; Redzia-Ogrodnik, B.; et al. Serum neurofilament light chain and initial severity of neurological disease predict the early neurological deterioration in Wilson’s disease. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2023, 123, 917–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Patient | Details of WD | Symptoms and Signs of CD | CD Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ueda et al., 2022 [24] | 57-year-old man with neurological WD diagnosed aged 20 | Initially on DPA 1000 mg/day and ZA 80 mg/day; ZA increased to 150 mg/day due to neurological progression (dysphagia with gastrostomy) Cu metabolism at CD diagnosis: Cp: 5.5 mg/dL Serum Cu: 11 µg/dL Urinary Cu excretion: 74 µg/24 h | Moderate distal weakness, hypotonia, absent tendon reflexes, sensory ataxia and severe sensory disturbances in all 4 limbs (numbness and paresthesia) Severe sensory motor polyneuropathy (EDX) Myelopathy in cervical MRI in posterior cord Anemia (Hgb 6.9 g/dL) | ZA and DPA cessation for 9 months, with increased Cu intake to 1.67 mg/day DPA introduced thereafter | Partial recovery after 3 months Dysesthesias reduced; about 40% improvement in gait MRI changes in spinal cord persisted Anemia stopped progressing (Hgb 9.3 g/dL after 3 weeks and 10.8 g/dL after 3 months) Cu metabolism: N/A |

| Wu et al., 2020 [20] | 18-year-old woman with neurological WD diagnosed aged 17 | Initial 1 year on DPA and TN but stopped due to ADR(skin rash after DPA, abdominal pain after TN). ZS initiated at 150 mg/day, increased to 225 mg/day Cu metabolism at CD diagnosis: Cp and serum Cu: N/A Urinary Cu excretion: “low” | Distal weakness of both legs, sensory disturbances of legs, falls Axonal sensory neuropathy (EDX) and abnormal SSEPs Myelopathy in thoracic MRI in posterior cord Hematology N/A | ZS cessation with Cu supplementation 10 mg/day for 6 months | Complete recovery after 6 months Complete resolution of neuropathy and myelopathy (no follow-up MRI provided) Cu metabolism: N/A |

| Cai et al., 2019 [23] | 12-year-old female with presymptomatic WD diagnosed aged 7 (abnormal LFTs that normalized during WD treatment) | ZG (150 mg elemental zinc), increased to 240 mg at age 8 due to initially increased LFT Cu metabolism at CD diagnosis: Cp: N/A Serum Cu: 12.7 µg/dL Urinary Cu excretion: 30 µg/24 h | Abnormal gait (no details) Brain MRI normal, spine MRI rejected by patient Anemia (Hgb 4.0 g/dL; RBC 1.37 M/µL), leukopenia (WBC 1.5 K/µL) and neutropenia (0.08 K/µL) | Temporary ZG cessation, blood transfusion | Complete recovery Gait disturbance subsided Hgb started to increase after 1 week, with normalization after 8 months (Hgb 11.7 g/dL, RBC 5.28 M/µL) Cu metabolism: N/A |

| Mohamed et al., 2018 [22] | 26-year-old woman with neurological WD diagnosed aged 13 | ZS 200 mg/day of elemental zinc, increased to 240 mg due to initially increased LFT Cu metabolism at CD diagnosis: Cp: 2 mg/dL Serum Cu: <0.1 µmol/L Urinary Cu excretion: N/A | Bone marrow biopsy: moderate dyserythropoiesis with defects in maturation Spine MRI and SSEPs not undertaken Anemia (as above), leukopenia (WBC 1.2 K/µL) and neutropenia (0.2 K/µL) | Temporary ZS cessation and supplementation Cu gluconate 2 mg/day After 8 months, ZS at 50% dose planned | Complete recovery Hgb normalization after 4 months (Hgb 12.2 g/dL, neutrophil 2.5 K/µL) Serum Cu 1 µmol/L at 8 months |

| Dzieżyc et al., 2014 [19] | 37-year-old asymptomatic woman diagnosed aged 21 (family screening) | 16 years on ZS 180 mg/day Cu metabolism at CD diagnosis: Cp: 0.92 mg/dL Serum Cu: <5 µg/dL Urinary Cu excretion: 11 µg/24 h | Paresthesias in fingers and toes for 3 months, weakness in lower limbs during fast walking Posterior column of the cervical cord (C2-Th1) myelopathy in spine MRI Myelopathy (few low-amplitude short-duration motor unit [EDX]) Leukopenia (WBC 2.9 K/µL) | ZS cessation for 9 months, DPA introduced later | CD symptoms disappeared after 6 months EDZ normalization; SSEPs abnormalities remained in dorsal column Improved WBC (6.0 K/µL) Cp: 5 mg/dL Serum Cu: 20 µg/dL Urinary Cu excretion: 12.5 µg/24 h |

| 46-year-old man with hepatic WD diagnosed aged 41 (compensated liver failure) | 5 years on ZS (180 mg/day) Cu metabolism at CD diagnosis: Cp: 0.5 mg/dL Serum Cu: <5 µg/dL Urinary Cu excretion: 6 µg/24 h | Upper respiratory tract infections Leukopenia (WBC 1.86 K/µL) Neutropenia (neutrophils 0.89 × 109/L) | Decreased ZS dose to 135 mg/day and further treat WD with decreased dose of ZS (with close follow-up) | Complete recovery after 12 months Improved hematology (WBC 3.3 K/µL; neutrophils 2.0 × 109/L) Cp: 1.18 mg/dL Serum Cu: 5 µg/dL Urinary Cu excretion: 10.5 µg/24 h | |

| 18-year-old woman with presymptomatic WD diagnosed aged 12 (family screening) | 6 years on ZS (180 mg/day) Cu metabolism at CD diagnosis: Cp: 0.9 mg/dL Serum Cu: 7 µg/dL Urinary Cu excretion: 12 µg/24 h | Anemia (RBC 3.2 M/µL) Leukopenia (WBC 2.3 K/µL) Neutropenia (neutrophils 0.17 × 109/L) SSEPs: impaired conduction in spinal dorsal column (refused MRI) | Cessation of ZS for 2 months initially (later for longer 1-year period) | Complete recovery after 1 year Improved hematology (WBC 7.3 K/µL; neutrophils: 5.1 × 109/L) Cp: 17 mg/dL Serum Cu: 44 µg/dL Urinary Cu excretion: 10 µg/24 h | |

| Rau et al., 2014 [21] | 16-year-old male diagnosed aged 14 (form not provided) | 1 year on DPA then switched to ZS (dose not described) due to anemia and neutropenia Cu metabolism at CD diagnosis: Cp: <2 mg/dL Serum Cu: 31 µg/dL Urinary Cu excretion: 32 µg/24 h | Anemia (Hgb 5.8 g/dL; RBC 1.9 M/µL) Leukopenia (WBC 1.4 × 109) Neutropenia (0.46 × 109/L) SSEPs, EDX, MRI of spine not undertaken | Cessation of ZS for 1 year, Cu supplementation 2.5 mg/day for a few months, DPA introduced later slowly | Complete recovery after 8 weeks: Improved hematology (Hgb 13.6 g/dL, RBC 5.3 M/µL, WBC 6.3 K/µL, neutrophils 3.23 × 109/L Serum Cu: 63 µg/dL Cp and urinary Cu excretion: N/A |

| Kaleagasi et al., 2013 [28] | 29-year-old patient (details not described) | Treatment with DPA and ZA (dose not known) Cu metabolism at CD diagnosis: Serum Cu: 0.3 µg/dL Cp and urinary Cu excretion: N/A | Recurrent seizures, complex partial seizures and secondary generalized seizures Hematology, SSEPs and MRI of head and spine not undertaken | ZA and DPA stopped and low Cu diet introduced | Complete recovery Seizures frequency decreased Serum Cu: 16 µg/dL Cp and urinary Cu excretion: N/A |

| Teodoro et al., 2013 [18] | 36-year-old man with neurological WD diagnosed aged 20 | 16 years on ZS 150 mg/day and TN 500 mg/day (few years on DPA 600 mg/day instead of TN due to lack of TN complicated by nephrotic syndrome, then TN and ZS 330 mg/day) Cu metabolism at CD diagnosis: Cp: 3 mg/dL Serum Cu: 13.3 µg/dL Urinary Cu excretion: 41 µg/24 h | Numbness of both hands and feet and gait worsening with falls Posterior dorsal cord myelopathy (in spine MRI) Mixed sensory/motor peripheral neuropathy (EDX) Hematology and SSEPs not undertaken | TN and ZS were substituted by ZA 100 mg/day, which was progressively reduced and stopped due to persistent CD After 1 year ZA 150 mg/day reintroduced | Partial improvement at 1 year Improvement in gait without support, improvement in electrophysiological assessment of neuropathy Myelopathy decreased in MRI Cp and serum Cu: N/A Urinary Cu excretion: 97 µg/24 h |

| Lozano Herrero et al., 2012 [17] | 56-year-old woman with hepatic WD diagnosed aged 18 | 28 years with DPA 750 mg/day, last 10 years on ZA 503 mg (150 mg elemental zinc) Cu metabolism at CD diagnosis: Cp: undetectable Serum Cu: 3 µg/dL Urinary Cu excretion: undetectable | Slowly progressive unstable gait with paresthesia of hands and feet Myelopathy in cervical cord C2-C7 in MRI EDX normal, abnormal SSEPs Anemia (Hgb 11.3 g/dL) Neutropenia (neutrophils 0.7 × 109/L) | ZA cessation and Cu supplementation (later ZA slowly introduced at low dose) | Minimal improvement during first few months Cp: 12.3 mg/dL Serum Cu: 36 µg/dL Urinary Cu excretion: 46 µg/24 h |

| Cortese et al., 2011 [15] | 51-year-old woman with neurological WD diagnosed aged 19 | 32 years of treatment, initially on DPA, then switched to ZS 600 mg/day (elemental zinc unknown) due to hyperintense reaction polyadenopathy Cu metabolism at CD diagnosis: Cp: N/A Serum Cu: 5 µg/dL Urinary Cu excretion: 20 µg/24 h | Distal limb paresthesia, sensory loss, and gait disturbances Sensory motor peripheral polyneuropathy (EDX) SSEPs and MRI of spinal cord normal Anemia (Hgb 6.5 g/dL) Neutropenia (neutrophils 0.25 × 109/L) | ZS reduction to 600 mg/day initially and substituted by ZA 150 mg/day (not data according to elemental zinc) and blood transfusions | Improvement in cytopenia and anemia without effect on neuropathy Cp: N/A Serum Cu: 64 µg/dL Urinary Cu excretion: 42 µg/24 h |

| Da Silva-Junior et al., 2011 [16] | 44-year-old woman with neurological WD diagnosed aged 29 (complete resolution of neurological symptoms in 1 year) | 15 years of treatment, initially on DPA but stopped due to ADR, then on ZA 450 mg/day (elemental zinc not known) Cu metabolism at CD diagnosis: Cp: 8 mg/dL Serum Cu: 3 µg/dL Urinary Cu excretion: 7.4 µg/24 h | Progressive numbness of feet, then also arms Peripheral sensory neuropathy Spinal cord myelopathy C1-C6 Leukopenia (WBC 2.7 × 109/L) | ZA cessation | Symptoms stabilized (partial improvement) 4 months later Serum Cu: 37 µg/dL CP and urinary Cu excretion: N/A |

| Benbir et al., 2010 [14] | 21-year-old man with neurological WD diagnosed aged 16 | 5 years on DPA 1200 mg/day and ZA 100 mg/day (180 mg/day) Cu metabolism at CD diagnosis: Cp: N/A Serum Cu: 2.2 µg/dL Urinary Cu excretion: 165 µg/24 h | Status epilepticus with partial seizures Epileptiform activity on EEG Lack of hematology results | Cessation of DPA and ZA, high Cu diet (discharged home on ZA only) Anti-convulsant treatment (levetiracetam and diazepam) | Complete seizures did not re-occur Serum Cu: 13.7 µg/dL CP and urinary Cu excretion: N/A |

| Horvath et al., 2010 [13] | 41-year-old man diagnosed with neurological WD aged 25 | On DPA but stopped after 6 months due to ADR, then on ZS (200 mg elemental zinc) for 14 years; increased to 245 mg for 1 year due to fatigue and agitation (CD symptoms) Cu metabolism at CD diagnosis: Cp: 2 g/dL Serum Cu: 0.1 µmol/L Urinary Cu excretion: 0.4 µmol/24 h | Gait disturbances, fatigue Anemia (Hgb 7.8 g/dL) Leukopenia (WBC 2.1 × 109/L) Neutropenia (neutrophils 0.26 × 109/L) Axonal sensory peripheral polyneuropathy with distal amyotrophy (EDX) Abnormal SSEPs MRI of spine normal | Cessation of ZS | Complete resolution of hematological changes in 10 months Polyneuropathy persisted at 1 year follow-up Cp: 0.02 g/L Serum Cu: 0.27 µmol/L Urinary Cu excretion: 0.35 µmol/24 h |

| Foubert-Samier et al., 2009 [12] | 43-year-old man diagnosed with neurological WD aged 15 | 18 years on TN up to 900 mg/day and ZA 400 mg/day (elemental zinc not known) Cu metabolism at CD diagnosis: Cp: <1 mg/dL Serum Cu: 0.5 µmol/L Urinary Cu excretion: 1.7 µmol/24 h | Distal limb weakness Sensory motor peripheral axonal neuropathy (EDX) Anemia (Hgb 10.6 g/dL) Neutropenia (neutrophils 0.95 × 109/L) | Cessation of ZA, and decreased TN dose (300 mg/day) then increased to 900 mg/day | Anemia and neutropenia disappeared Neuropathy persisted at 2-year follow-up Cu metabolism: N/A |

| Narayan et al., 2006 [11] | 13-year-old male with neurological WD diagnosed aged 9 | 4 years on DPA 750 mg/day and ZS 280 mg/day (elemental zinc not known) Cu metabolism at CD diagnosis: Cp: 2.34 mg/dL Serum Cu: 16 µg/dL Urinary Cu excretion: N/A | Sensory disturbances in legs (decreased vibratory on joints) Anemia (no results provided) Demyelination in brain CT (white matter tracts) | Not provided | Not provided |

| Karunajeewa et al., 1998 [29] | 44-year-old man with neurological WD diagnosed aged 21 | Initially on DPA 1000 mg/day, reduced to 500 mg/day due to leukopenia after 6 months. Then on TN for 2 years, switched to DPA with ZS for 11 years. Switched to TH 200 mg/day and ZS 440 mg/day (elemental zinc not known) Cu metabolism at CD diagnosis: Cp: 2 mg/dL Serum Cu: 2 µmol/L Urinary Cu excretion: 0.1 µmol/24 h | Anemia (Hgb 50 g/dL) Leukopenia (WBC 1 K/µL) Neutropenia (0.36 × 109/L) Bone marrow biopsy showed marked hypoplasia | ZS and TH cessation for 9 months, filgrastim commenced, neutropenia disappeared, then reintroduction of TH 50 mg/day after 8 months | After 4 weeks: improved hematology (Hgb 11.6 g/dL; WBC 4.4 K/µL) Bone marrow biopsy showed mild hypocellularity and left shifted granulopoiesis Cu metabolism: N/A |

| Karunajeewa et al., 1998 [29] | 34-year-old woman with hepatic WD diagnosed aged 17 | On DPA 2000 mg/day initially. After splenectomy, increased to 2500 mg/day for 8 years due to excessive Cu liver deposition; switched to TH 200 mg/day Cu metabolism: N/A | Anemia (Hgb 7.1 g/dL) Neutropenia (neutrophils 0.35 × 109/L) Low Cu levels in liver biopsy: 46 µg/g | TH cessation for 4 weeks, reintroduced at lower dose of 50 mg/day | After 4 weeks: improved hematology (Hgb 11.5 g/dL, neutrophils 4.9 × 109/L) Cu metabolism: N/A |

| Van Den Hamer & Hoogenrad 1989 [10] | 56-year-old patient diagnosed aged 25 | 31 years of treatment, initially on DPA then switched to ZS 1200 mg/day (elemental zinc not known). CD occurred 2 years after switch Cu metabolism at CD diagnosis: Serum Cu: 0.05 µg/mL Cp and urinary Cu excretion: N/A | Anemia with neutropenia | Parenteral Cu supplementation | Complete recovery Normalization of hematology in a few days Cu metabolism: N/A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Litwin, T.; Antos, A.; Bembenek, J.; Przybyłkowski, A.; Kurkowska-Jastrzębska, I.; Skowrońska, M.; Członkowska, A. Copper Deficiency as Wilson’s Disease Overtreatment: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2424. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13142424

Litwin T, Antos A, Bembenek J, Przybyłkowski A, Kurkowska-Jastrzębska I, Skowrońska M, Członkowska A. Copper Deficiency as Wilson’s Disease Overtreatment: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics. 2023; 13(14):2424. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13142424

Chicago/Turabian StyleLitwin, Tomasz, Agnieszka Antos, Jan Bembenek, Adam Przybyłkowski, Iwona Kurkowska-Jastrzębska, Marta Skowrońska, and Anna Członkowska. 2023. "Copper Deficiency as Wilson’s Disease Overtreatment: A Systematic Review" Diagnostics 13, no. 14: 2424. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13142424

APA StyleLitwin, T., Antos, A., Bembenek, J., Przybyłkowski, A., Kurkowska-Jastrzębska, I., Skowrońska, M., & Członkowska, A. (2023). Copper Deficiency as Wilson’s Disease Overtreatment: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics, 13(14), 2424. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13142424