Phenotypic Diversity of 15q11.2 BP1–BP2 Deletion in Three Korean Families with Development Delay and/or Intellectual Disability: A Case Series and Literature Review

Abstract

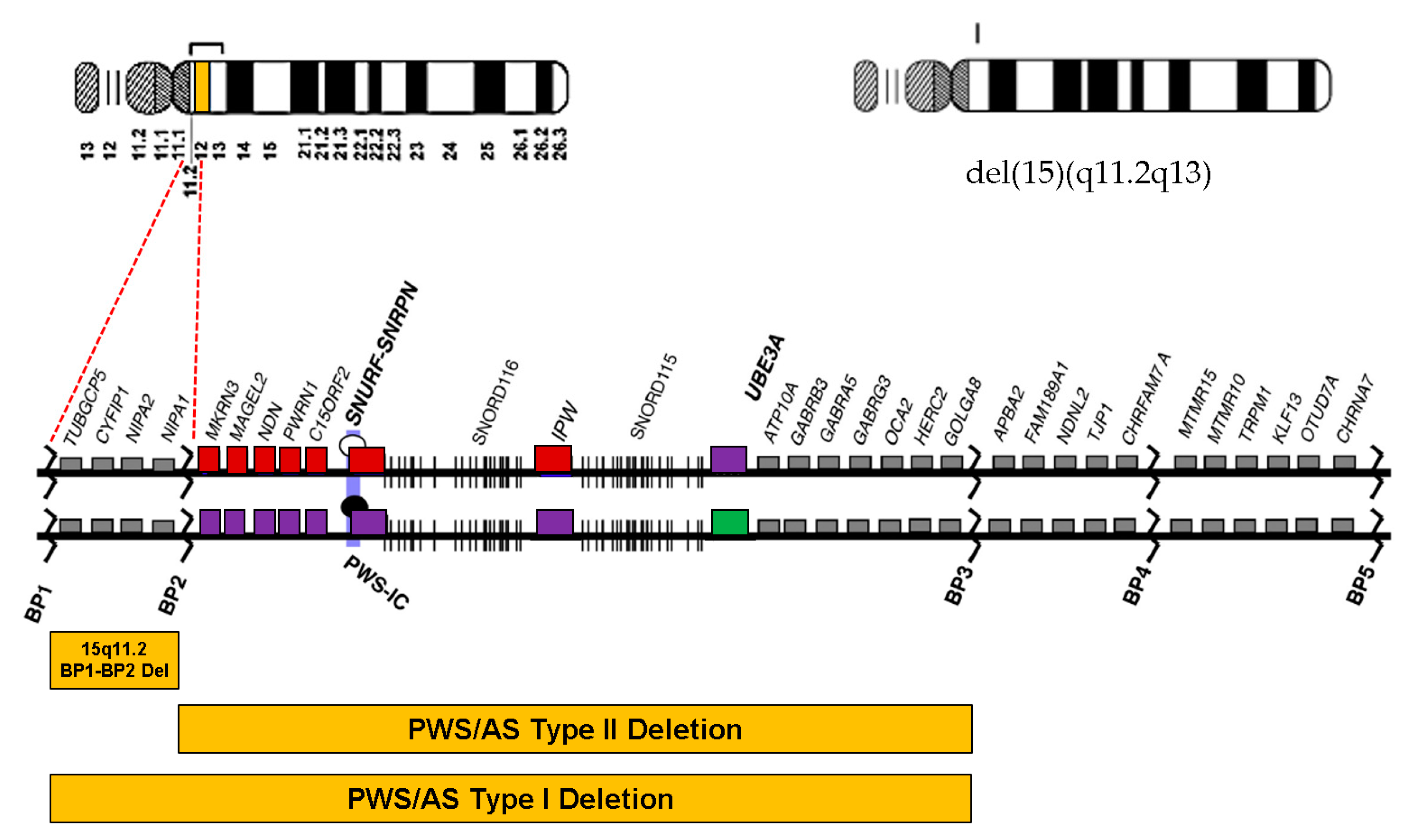

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples and DNA Extraction

2.2. Array Comparative Genomic Hybridization

2.3. Exome Sequencing

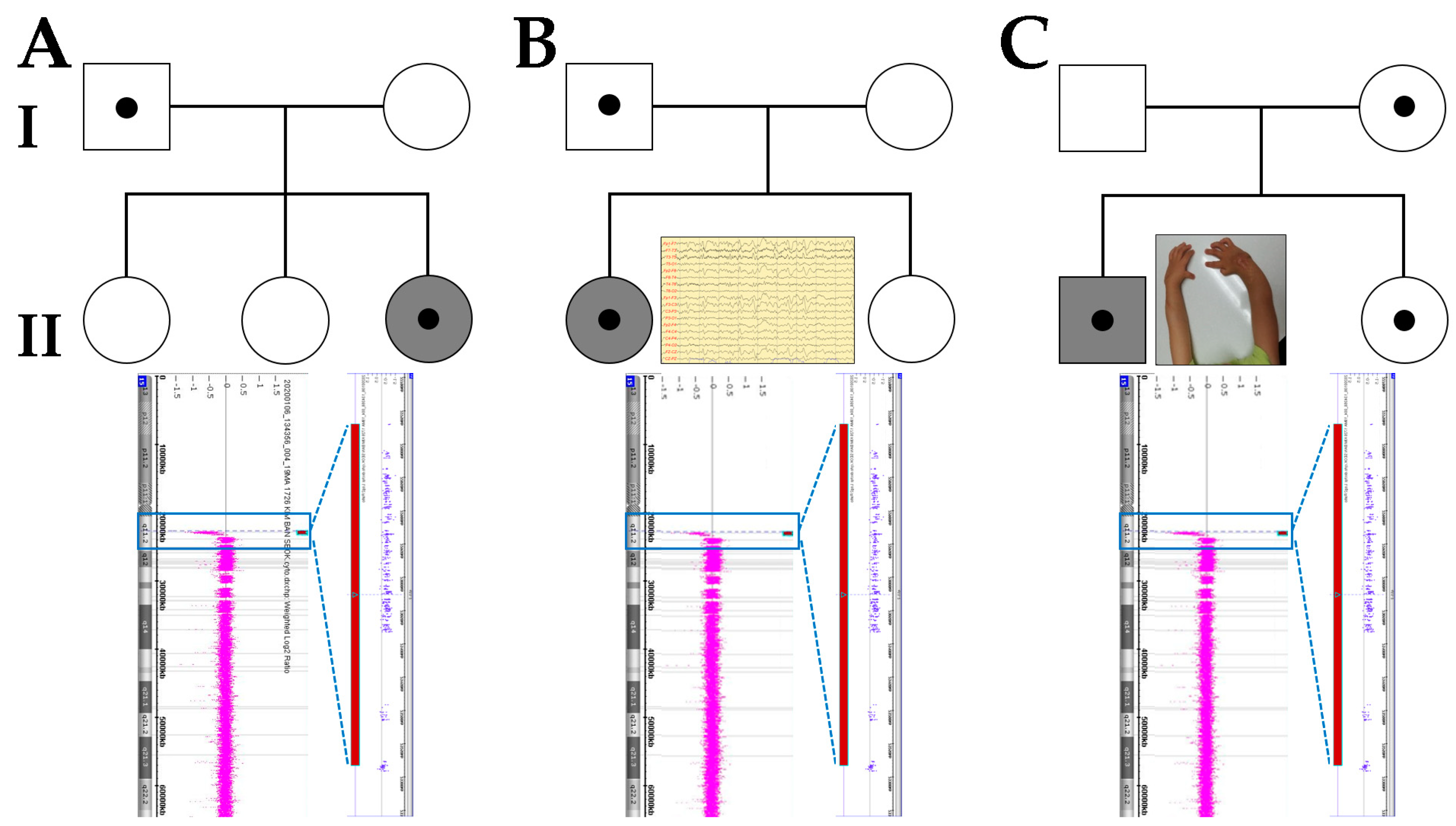

3. Case Presentation

4. Results

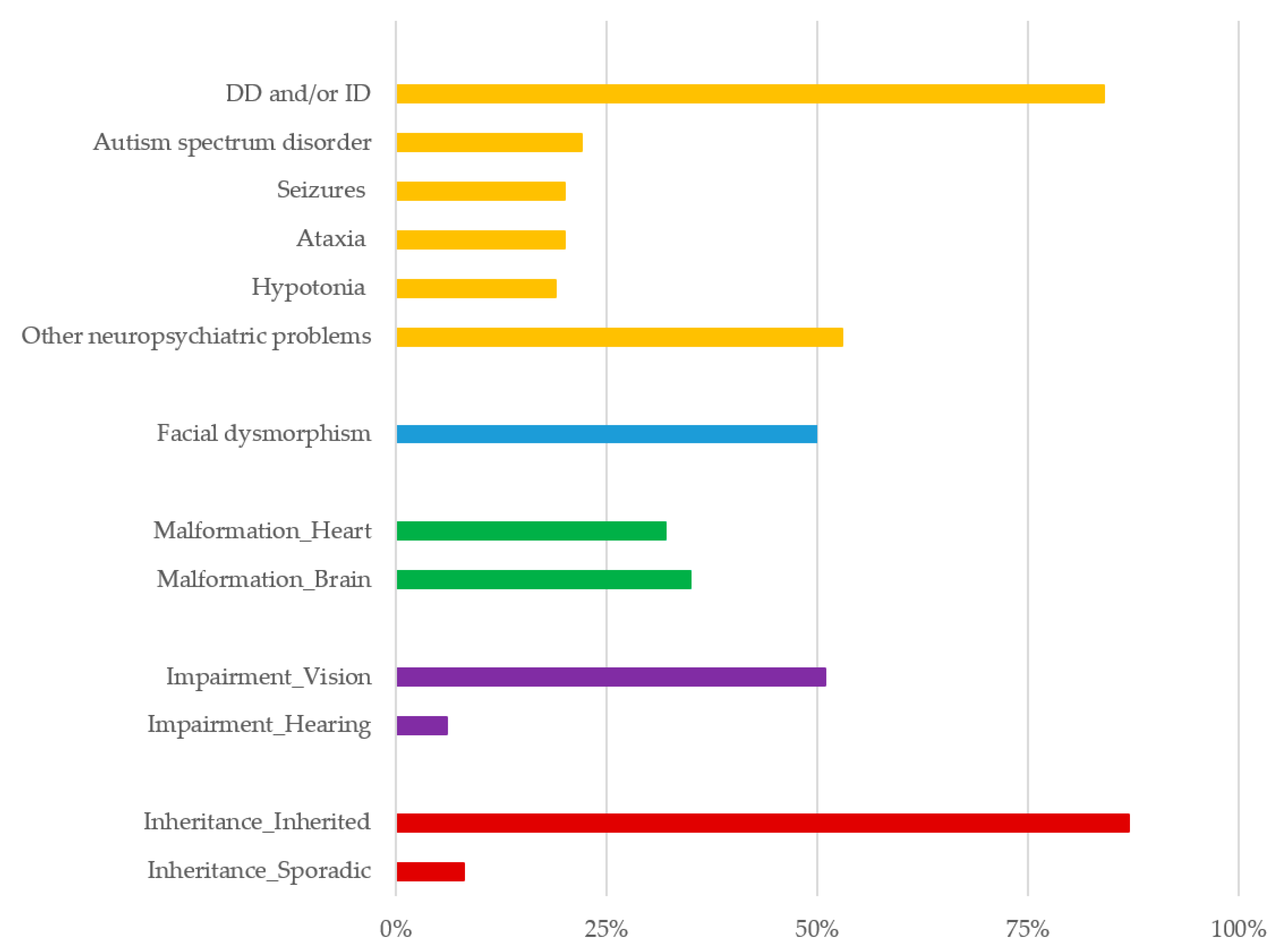

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Christian, S.L.; Fantes, J.A.; Mewborn, S.K.; Huang, B.; Ledbetter, D.H. Large genomic duplicons map to sites of instability in the Prader-Willi/Angelman syndrome chromosome region (15q11-q13). Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999, 8, 1025–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masurel-Paulet, A.; Andrieux, J.; Callier, P.; Cuisset, J.M.; Le Caignec, C.; Holder, M.; Thauvin-Robinet, C.; Doray, B.; Flori, E.; Alex-Cordier, M.P.; et al. Delineation of 15q13.3 microdeletions. Clin. Genet. 2010, 78, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafi, S.K.; Butler, M.G. The 15q11.2 BP1-BP2 Microdeletion (Burnside-Butler) Syndrome: In Silico Analyses of the Four Coding Genes Reveal Functional Associations with Neurodevelopmental Phenotypes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doornbos, M.; Sikkema-Raddatz, B.; Ruijvenkamp, C.A.; Dijkhuizen, T.; Bijlsma, E.K.; Gijsbers, A.C.; Hilhorst-Hofstee, Y.; Hordijk, R.; Verbruggen, K.T.; Kerstjens-Frederikse, W.S.; et al. Nine patients with a microdeletion 15q11.2 between breakpoints 1 and 2 of the Prader-Willi critical region, possibly associated with behavioural disturbances. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2009, 52, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnside, R.D.; Pasion, R.; Mikhail, F.M.; Carroll, A.J.; Robin, N.H.; Youngs, E.L.; Gadi, I.K.; Keitges, E.; Jaswaney, V.L.; Papenhausen, P.R.; et al. Microdeletion/microduplication of proximal 15q11.2 between BP1 and BP2: A susceptibility region for neurological dysfunction including developmental and language delay. Hum. Genet. 2011, 130, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelmoity, A.T.; LePichon, J.B.; Nyp, S.S.; Soden, S.E.; Daniel, C.A.; Yu, S. 15q11.2 proximal imbalances associated with a diverse array of neuropsychiatric disorders and mild dysmorphic features. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatrics 2012, 33, 570–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanlerberghe, C.; Petit, F.; Malan, V.; Vincent-Delorme, C.; Bouquillon, S.; Boute, O.; Holder-Espinasse, M.; Delobel, B.; Duban, B.; Vallee, L.; et al. 15q11.2 microdeletion (BP1-BP2) and developmental delay, behaviour issues, epilepsy and congenital heart disease: A series of 52 patients. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2015, 58, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.M.; Butler, M.G. The 15q11.2 BP1-BP2 microdeletion syndrome: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 4068–4082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, J.A.; Coe, B.P.; Eichler, E.E.; Cuckle, H.; Shaffer, L.G. Estimates of penetrance for recurrent pathogenic copy-number variations. Genet. Med. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 2013, 15, 478–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S.; Kkani, P.; Ramasubramanian, C.; Kumar, S.G.; Monisha, R.; Prasad Rao, G.; Mohan, K.N. Analysis of 15q11.2 CNVs in an Indian population with schizophrenia. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2019, 83, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sempere Pérez, A.; Manchón Trives, I.; Palazón Azorín, I.; Alcaraz Más, L.; Pérez Lledó, E.; Galán Sánchez, F. 15Q11.2 (BP1-BP2) microdeletion, a new syndrome with variable expressivity. Anales Pediatria 2011, 75, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murthy, S.K.; Nygren, A.O.; El Shakankiry, H.M.; Schouten, J.P.; Al Khayat, A.I.; Ridha, A.; Al Ali, M.T. Detection of a novel familial deletion of four genes between BP1 and BP2 of the Prader-Willi/Angelman syndrome critical region by oligo-array CGH in a child with neurological disorder and speech impairment. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2007, 116, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von der Lippe, C.; Rustad, C.; Heimdal, K.; Rodningen, O.K. 15q11.2 microdeletion—Seven new patients with delayed development and/or behavioural problems. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2011, 54, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrigal, I.; Rodríguez-Revenga, L.; Xunclà, M.; Milà, M. 15q11.2 microdeletion and FMR1 premutation in a family with intellectual disabilities and autism. Gene 2012, 508, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usrey, K.M.; Williams, C.A.; Dasouki, M.; Fairbrother, L.C.; Butler, M.G. Congenital Arthrogryposis: An Extension of the 15q11.2 BP1-BP2 Microdeletion Syndrome? Case Rep. Genet. 2014, 2014, 127258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, G.M.; Coe, B.P.; Girirajan, S.; Rosenfeld, J.A.; Vu, T.H.; Baker, C.; Williams, C.; Stalker, H.; Hamid, R.; Hannig, V.; et al. A copy number variation morbidity map of developmental delay. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 838–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cafferkey, M.; Ahn, J.W.; Flinter, F.; Ogilvie, C. Phenotypic features in patients with 15q11.2(BP1-BP2) deletion: Further delineation of an emerging syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2014, 164, 1916–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, B.; Bassett, A.; Chitayat, D.; Chong, K.; Feldman, M.; Flanagan, J.; Goobie, S.; Kawamura, A.; Lowther, C.; Prasad, C.; et al. Deletion of 15q11.2(BP1-BP2) region: Further evidence for lack of phenotypic specificity in a pediatric population. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2015, 167, 2098–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefansson, H.; Meyer-Lindenberg, A.; Steinberg, S.; Magnusdottir, B.; Morgen, K.; Arnarsdottir, S.; Bjornsdottir, G.; Walters, G.B.; Jonsdottir, G.A.; Doyle, O.M.; et al. CNVs conferring risk of autism or schizophrenia affect cognition in controls. Nature 2014, 505, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jønch, A.E.; Douard, E.; Moreau, C.; Van Dijck, A.; Passeggeri, M.; Kooy, F.; Puechberty, J.; Campbell, C.; Sanlaville, D.; Lefroy, H.; et al. Estimating the effect size of the 15Q11.2 BP1-BP2 deletion and its contribution to neurodevelopmental symptoms: Recommendations for practice. J. Med. Genet. 2019, 56, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Meer, D.; Sønderby, I.E.; Kaufmann, T.; Walters, G.B.; Abdellaoui, A.; Ames, D.; Amunts, K.; Andersson, M.; Armstrong, N.J.; Bernard, M.; et al. Association of Copy Number Variation of the 15q11.2 BP1-BP2 Region With Cortical and Subcortical Morphology and Cognition. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Liu, X.; Deng, X. Genetic basis of pediatric epilepsy syndromes. Exp. Med. 2017, 13, 2129–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D.; Johnson, S.M.; Young, D.; Iwamoto, L.; Sood, S.; Slavin, T.P. Expanding the BP1-BP2 15q11.2 Microdeletion Phenotype: Tracheoesophageal Fistula and Congenital Cataracts. Case Rep. Genet. 2013, 2013, 801094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jerkovich, A.M.; Butler, M.G. Further phenotypic expansion of 15q11.2 BP1-BP2 microdeletion (Burnside-Butler) syndrome. J. Pediatric Genet. 2014, 3, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, M.; Canizares, M.F.; Bohn, D.; James, M.A.; Samora, J.; Steinman, S.; Wall, L.B.; Bauer, A.S. Association of Radial Longitudinal Deficiency and Thumb Hypoplasia: An Update Using the CoULD Registry. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2020, 102, 1815–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakkasjarvi, N.; Koskimies, E.; Ritvanen, A.; Nietosvaara, Y.; Makitie, O. Characteristics and associated anomalies in radial ray deficiencies in Finland—A population-based study. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2013, 161a, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmakky, A.; Stanghellini, I.; Landi, A.; Percesepe, A. Role of Genetic Factors in the Pathogenesis of Radial Deficiencies in Humans. Curr. Genom. 2015, 16, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.W.; Serrano, M.; Loddo, S.; Robinson, C.; Alesi, V.; Dallapiccola, B.; Novelli, A.; Butler, M.G. Parent-of-Origin Effects in 15q11.2 BP1-BP2 Microdeletion (Burnside-Butler) Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- François, C.; Grabli, D.; McCairn, K.; Jan, C.; Karachi, C.; Hirsch, E.C.; Féger, J.; Tremblay, L. Behavioural disorders induced by external globus pallidus dysfunction in primates II. Anatomical study. Brain J. Neurol. 2004, 127, 2055–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabli, D.; McCairn, K.; Hirsch, E.C.; Agid, Y.; Féger, J.; François, C.; Tremblay, L. Behavioural disorders induced by external globus pallidus dysfunction in primates: I. Behavioural study. Brain J. Neurol. 2004, 127, 2039–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Oakley, B.R. In vivo analysis of the functions of gamma-tubulin-complex proteins. J. Cell Sci. 2009, 122, 4218–4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, K.; Kuroda, S.; Fukata, M.; Nakamura, T.; Nagase, T.; Nomura, N.; Matsuura, Y.; Yoshida-Kubomura, N.; Iwamatsu, A.; Kaibuchi, K. p140Sra-1 (specifically Rac1-associated protein) is a novel specific target for Rac1 small GTPase. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccorso, C.M.; Spatuzza, M.; Di Marco, B.; Gloria, A.; Barrancotto, G.; Cupo, A.; Musumeci, S.A.; D’Antoni, S.; Bardoni, B.; Catania, M.V. Fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) interacting proteins exhibit different expression patterns during development. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. Off. J. Int. Soc. Dev. Neurosci. 2015, 42, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, L.R.; Hall, A.L.; Kang, S.-H.L.; Shaw, C.A.; Beaudet, A.L. High frequency of known copy number abnormalities and maternal duplication 15q11-q13 in patients with combined schizophrenia and epilepsy. BMC Med. Genet. 2011, 12, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, J.H.; Locke, D.P.; Greally, J.M.; Knoll, J.H.; Ohta, T.; Dunai, J.; Yavor, A.; Eichler, E.E.; Nicholls, R.D. Identification of four highly conserved genes between breakpoint hotspots BP1 and BP2 of the Prader-Willi/Angelman syndromes deletion region that have undergone evolutionary transposition mediated by flanking duplicons. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003, 73, 898–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainier, S.; Chai, J.H.; Tokarz, D.; Nicholls, R.D.; Fink, J.K. NIPA1 gene mutations cause autosomal dominant hereditary spastic paraplegia (SPG6). Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003, 73, 967–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Song, C.; Guo, H.; Xu, P.; Huang, W.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, J.; Li, C.X.; Du, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Distinct novel mutations affecting the same base in the NIPA1 gene cause autosomal dominant hereditary spastic paraplegia in two Chinese families. Hum. Mutat. 2005, 25, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, M.G. Magnesium Supplement and the 15q11.2 BP1-BP2 Microdeletion (Burnside-Butler) Syndrome: A Potential Treatment? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Sang, T.; Zhang, F.; Ji, T.; Huang, Q.; Xie, H.; Du, R.; Cai, B.; et al. NIPA2 located in 15q11.2 is mutated in patients with childhood absence epilepsy. Hum. Genet. 2012, 131, 1217–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, F.; Xie, H.; Chan, P.; Wu, X. NIPA2 mutations are correlative with childhood absence epilepsy in the Han Chinese population. Hum. Genet. 2014, 133, 675–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, N.J.; Owen, M.J. A Developmental Perspective on the Convergence of Genetic Risk Factors for Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 2020, 87, 98–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serdarevic, F.; Tiemeier, H.; Jansen, P.R.; Alemany, S.; Xerxa, Y.; Neumann, A.; Robinson, E.; Hillegers, M.H.J.; Verhulst, F.C.; Ghassabian, A. Polygenic Risk Scores for Developmental Disorders, Neuromotor Functioning During Infancy, and Autistic Traits in Childhood. Biol. Psychiatry 2020, 87, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Clinical Manifestations | A-II-3 | B-II-1 | C-II-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex/Age (Year) at Diagnosis | F/3 | F/6 | M/3 |

| Inheritance | Paternal | Paternal | Maternal |

| Parent Status | Unaffected | Unaffected | Unaffected |

| Height < −2SD | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Obesity | Present | Absent | Absent |

| Auxology | |||

| IUGR | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Failure to Thrive | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Microcephaly | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Facial Dysmorphism | |||

| High Forehead | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Hypertelorism | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Dysplastic Ears | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Long Philtrum | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| High Arched Palate | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Micrognathia | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Cleft Palate/lip | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Deformity/Impairments | |||

| Brain | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Heart | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Vision | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Hearing | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Neurology–Psychiatry | |||

| Intellectual Disability | Present | Present | Present |

| Ataxia | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Seizures | Absent | Present | Absent |

| ASD | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| ADHD | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| OCD | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Other Psychobehavioral Problems | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Neurodevelopment | |||

| Hypotonia | Present | Present | Present |

| Delayed Motor Milestones | Present | Present | Present |

| Speech Impairment | Present | Present | Present |

| Learning Difficulties | Present | Present | Present |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, J.Y.; Park, J. Phenotypic Diversity of 15q11.2 BP1–BP2 Deletion in Three Korean Families with Development Delay and/or Intellectual Disability: A Case Series and Literature Review. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 722. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11040722

Han JY, Park J. Phenotypic Diversity of 15q11.2 BP1–BP2 Deletion in Three Korean Families with Development Delay and/or Intellectual Disability: A Case Series and Literature Review. Diagnostics. 2021; 11(4):722. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11040722

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Ji Yoon, and Joonhong Park. 2021. "Phenotypic Diversity of 15q11.2 BP1–BP2 Deletion in Three Korean Families with Development Delay and/or Intellectual Disability: A Case Series and Literature Review" Diagnostics 11, no. 4: 722. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11040722

APA StyleHan, J. Y., & Park, J. (2021). Phenotypic Diversity of 15q11.2 BP1–BP2 Deletion in Three Korean Families with Development Delay and/or Intellectual Disability: A Case Series and Literature Review. Diagnostics, 11(4), 722. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11040722