A Systematic Review of Asthma Phenotypes Derived by Data-Driven Methods

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Assessment

3. Results

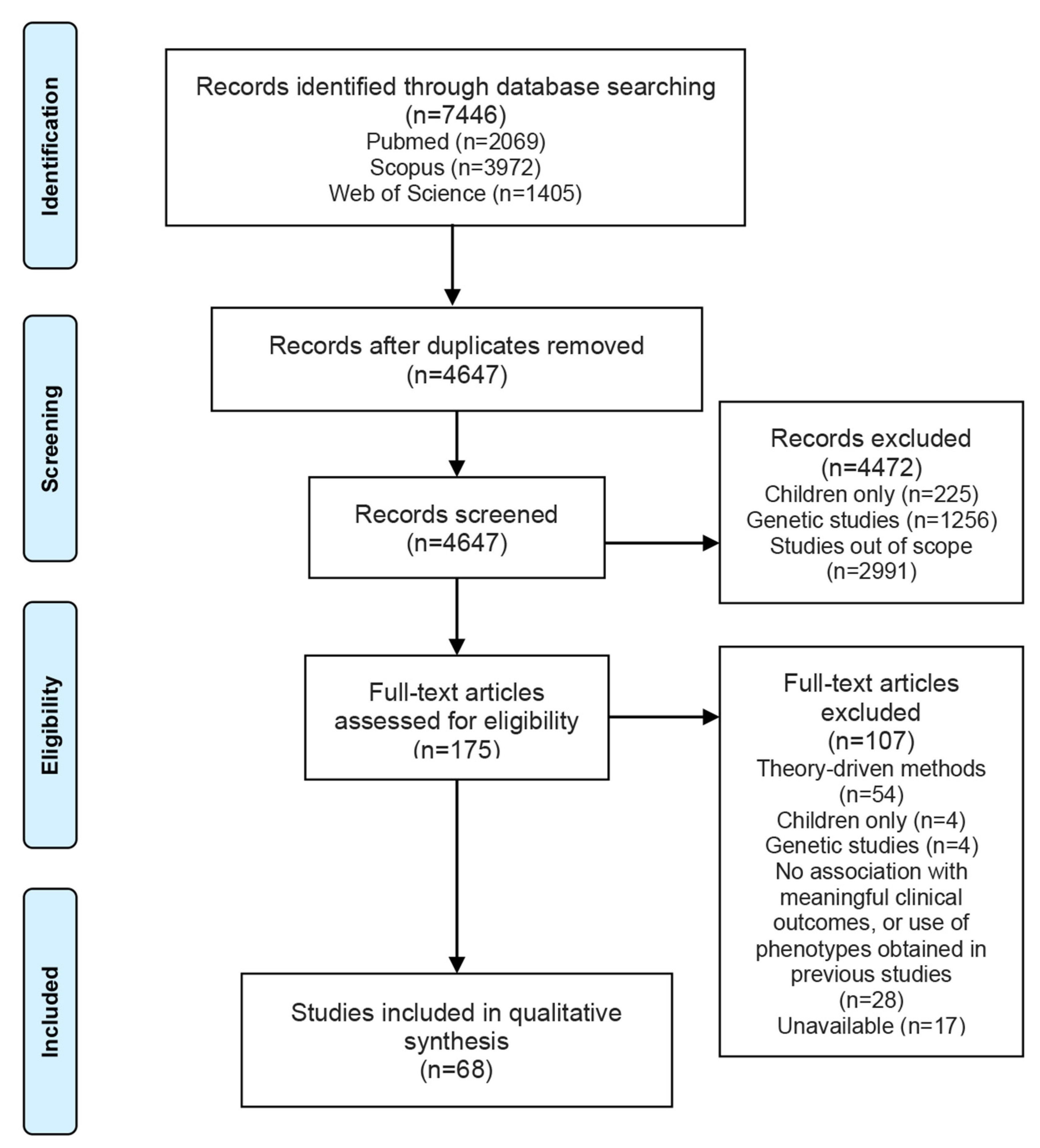

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

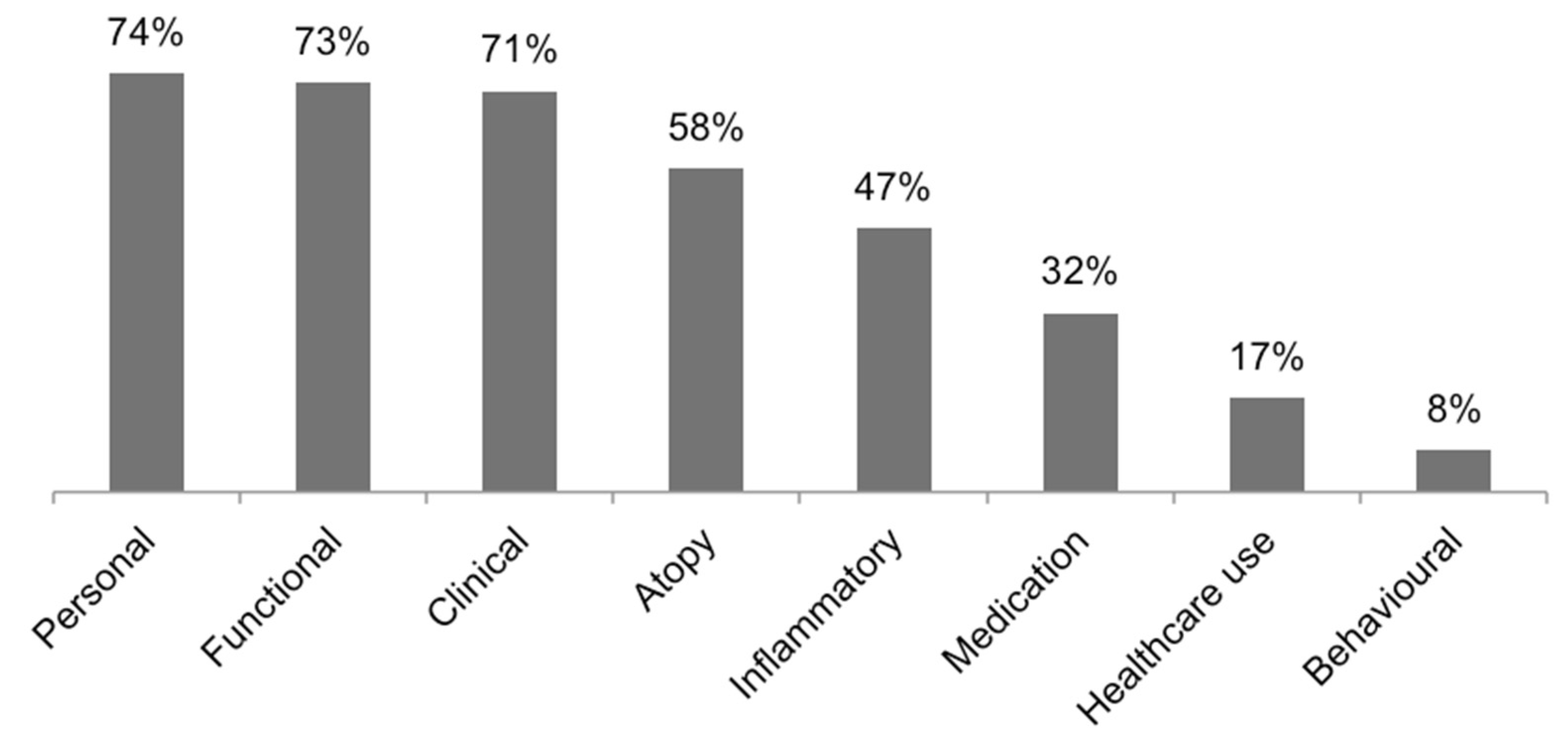

3.3. Asthma Phenotypes

3.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Study ID (Author, Year) | Domains | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | F | C | A | I | M | H | B | |

| Hierarchical Cluster Analysis | ||||||||

| Baptist, 2018 [22] | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Belhassen, 2016 [23] | x | |||||||

| Bhargava, 2019 [15] | Variables were not retrieved. | |||||||

| Delgado-Eckert, 2018 [30] | x | |||||||

| Fingleton, 2015 [31] | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Fingleton, 2017 [32] | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Khusial, 2017 [39] | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Konno, 2015 [44] | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Loureiro, 2015 [8] | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Moore, 2010 [51] | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Nagasaki, 2014 [54] | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Qiu, 2018 [60] | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Sakagami, 2014 [63] | x | x | x | |||||

| Schatz, 2014 [64] | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Seino, 2018 [65] | x | x | x | |||||

| Sendín-Hernández, 2018 [67] | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Sutherland, 2012 [70] | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Weatherall, 2009 [75] | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Ye, 2017 [77] | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Youroukova, 2017 [78] | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| K-means Cluster Analysis | ||||||||

| Agache, 2010 [17] | x | x | ||||||

| Amelink, 2013 [21] | x | x | x | |||||

| Choi, 2017 [27] | x | |||||||

| Deccache, 2018 [29] | x | |||||||

| Gupta, 2010 [16] | Variables were not retrieved. | |||||||

| Lee, 2017 [47] | x | x | x | |||||

| Musk, 2011 [53] | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Oh, 2020 [56] | x | x | ||||||

| Park, 2015 [57] | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Park, 2013 [58] | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Rakowski, 2019 [61] | x | |||||||

| Rootmensen, 2016 [62] | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Tanaka, 2018 [71] | x | |||||||

| Tay, 2019 [72] | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Wu, 2014 [10] | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Zaihra, 2016 [79] | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Two-step Cluster Analysis | ||||||||

| Haldar, 2008 [33] | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Hsiao, 2019 [34] | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Ilmarinen, 2017 [35] | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Jang, 2013 [36] | x | x | ||||||

| Kim, 2018 [40] | x | |||||||

| Kim, 2017 [41] | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Kim, 2013 [42] | x | x | x | |||||

| Konstantellou, 2015 [45] | x | x | x | |||||

| Labor, 2017 [46] | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Lemiere, 2014 [49] | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Newby, 2014 [55] | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Serrano-Pariente, 2015 [68] | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Wang, 2017 [74] | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Wu, 2018 [76] | x | x | x | |||||

| K-medoids Cluster Analysis | ||||||||

| Kisiel, 2020 [43] | x | x | x | |||||

| Lefaudeux, 2017 [48] | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Loza, 2016 [9] | x | x | x | |||||

| Sekiya, 2016 [66] | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Latent Class Analysis | ||||||||

| Amaral, 2019 [19] | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Amaral, 2019 [20] | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Bochenek, 2014 [24] | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Chanoine, 2018 [26] | x | |||||||

| Couto, 2018 [28] | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Jeong, 2017 [38] | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Makikyro, 2017 [50] | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Siroux, 2011 [69] | x | x | x | x | ||||

| van der Molen, 2018 [73] | x | |||||||

| Factor Analysis | ||||||||

| Alves, 2008 [18] | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Moore, 2014 [52] | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Latent Transition Analysis//Expectation-maximization | ||||||||

| Boudier, 2013 [25] | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Janssens, 2012 [37] | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Latent Mixture Modeling | ||||||||

| Park, 2019 [59] | x | x | ||||||

| Study ID (Author, Year) | Label |

|---|---|

| Hierarchical Cluster Analysis | |

| Baptist, 2018 [22] |

|

| Belhassen, 2016 [23] |

|

| Bhargava, 2019 [15] |

|

| Delgado-Eckert, 2018 [30] |

|

| Fingleton, 2015 [31] |

|

| Fingleton, 2017 [32] |

|

| Khusial, 2017 [39] |

|

| Konno, 2015 [44] |

|

| Loureiro, 2015 [8] |

|

| Moore, 2010 [51] |

|

| Nagasaki, 2014 [54] |

|

| Qiu, 2018 [60] |

|

| Sakagami, 2014 [63] |

|

| Schatz, 2014 [64] |

|

| Seino, 2018 [65] |

|

| Sendín-Hernández, 2018 [67] |

|

| Sutherland, 2012 [70] |

|

| Weatherall, 2009 [75] |

|

| Ye, 2017 [77] |

|

| Youroukova, 2017 [78] |

|

| K-means Cluster Analysis | |

| Agache, 2010 [17] |

|

| Amelink, 2013 [21] |

|

| Choi, 2017 [27] |

|

| Deccache, 2018 [29] |

|

| Gupta, 2010 [16] |

|

| Lee, 2017 [47] |

|

| Musk, 2011 [53] |

|

| Oh, 2020 [56] |

|

| Park, 2015 [57] | Primary Cohort/Secondary Cohort:

|

| Park, 2013 [58] |

|

| Rakowski, 2019 [61] |

|

| Rootmensen, 2016 [62] |

|

| Tanaka, 2018 [71] |

|

| Tay, 2019 [72] |

|

| Wu, 2014 [10] |

|

| Zaihra, 2016 [79] |

|

| Two-step Cluster Analysis | |

| Haldar, 2008 [33] | Primary-care:

|

| Hsiao, 2019 [34] | Females:

|

| Ilmarinen, 2017 [35] |

|

| Jang, 2013 [36] |

|

| Kim, 2018 [40] |

|

| Kim, 2017 [41] |

|

| Kim, 2013 [42] |

|

| Konstantellou, 2015 [45] |

|

| Labor, 2017 [46] |

|

| Lemiere, 2014 [49] |

|

| Newby, 2014 [55] |

|

| Serrano-Pariente, 2015 [68] |

|

| Wang, 2017 [74] |

|

| Wu, 2018 [76] |

|

| K-medoids Cluster Analysis | |

| Kisiel, 2020 [43] |

|

| Lefaudeux, 2017 [48] |

|

| Loza, 2016 [9] |

|

| Sekiya, 2016 [66] |

|

| Latent Class Analysis | |

| Amaral, 2019 [19] |

|

| Amaral, 2019 [20] |

|

| Bochenek, 2014 [24] |

|

| Chanoine, 2018 [26] |

|

| Couto, 2018 [28] |

|

| Jeong, 2017 [38] |

|

| Makikyro, 2017 [50] | Female:

|

| Siroux, 2011 [69] | EGEA2 sample:

|

| van der Molen, 2018 [73] |

|

| Factor Analysis | |

| Alves, 2008 [18] |

|

| Moore, 2014 [52] |

|

| Latent Transition Analysis//Expectation-maximization | |

| Boudier, 2013 [25] |

|

| Janssens, 2012 [37] |

|

| Latent Mixture Modeling | |

| Park, 2019 [59] | Prebronchodilator FEV1% predicted:

|

References

- Masoli, M.; Fabian, D.; Holt, S.; Beasley, R. Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) Program The global burden of asthma: Executive summary of the GINA Dissemination Committee Report. Allergy 2004, 59, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulet, L.-P.; Reddel, H.K.; Bateman, E.; Pedersen, S.; Fitzgerald, J.M.; O’Byrne, P.M. The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA): 25 years later. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 54, 1900598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everitt, B.S. Commentary: Classification and cluster analysis. BMJ 1995, 311, 535–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bousquet, J.; Anto, J.M.; Sterk, P.J.; Adcock, I.M.; Chung, K.F.; Roca, J.; Agusti, A.; Brightling, C.; Cambon-Thomsen, A.; Cesario, A.; et al. Systems medicine and integrated care to combat chronic noncommunicable diseases. Genome Med. 2011, 3, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padem, N.; Saltoun, C. Classification of asthma. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2019, 40, 385–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, A.O.; Ritchie, M.D. Informatics and machine learning to define the phenotype. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2018, 18, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, S.T.; Collins, L.M.; Lemmon, D.R.; Schafer, J.L. PROC LCA: A SAS Procedure for Latent Class Analysis. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2007, 14, 671–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, C.; Sa-Couto, P.; Todo-Bom, A.; Bousquet, J. Cluster analysis in phenotyping a Portuguese population. Rev. Port. de Pneumol. 2015, 21, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loza, M.J.; Djukanovic, R.; Chung, K.F.; Horowitz, D.; Ma, K.; Branigan, P.; Barnathan, E.S.; Susulic, V.S.; Silkoff, P.E.; Sterk, P.J.; et al. Validated and longitudinally stable asthma phenotypes based on cluster analysis of the ADEPT study. Respir. Res. 2016, 17, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Bleecker, E.; Moore, W.; Busse, W.W.; Castro, M.; Chung, K.F.; Calhoun, W.J.; Erzurum, S.; Gaston, B.; Israel, E.; et al. Unsupervised phenotyping of Severe Asthma Research Program participants using expanded lung data. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 133, 1280–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.M.D.C.; Pimenta, C.A.D.M.; Nobre, M.R.C. The PICO strategy for the research question construction and evidence search. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2007, 15, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem. Med. 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, S.; Holla, A.D.; Jayaraj, B.S.; Praveena, A.S.; Ravi, S.; Khurana, S.; Mahesh, P.A. Distinct asthma phenotypes with low maximal attainment of lung function on cluster analysis. J. Asthma 2021, 58, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Siddiqui, S.; Haldar, P.; Entwisle, J.J.; Mawby, D.; Wardlaw, A.J.; Bradding, P.; Pavord, I.D.; Green, R.H.; Brightling, C. Quantitative analysis of high-resolution computed tomography scans in severe asthma subphenotypes. Thorax 2010, 65, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agache, I.; Ciobanu, C. Risk Factors and Asthma Phenotypes in Children and Adults with Seasonal Allergic Rhinitis. Physician Sportsmed. 2010, 38, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, R.D.S.A.; Vianna, F.D.A.F.; Pereira, C.A.D.C. Fenótipos clínicos de asma grave. J. Bras. de Pneumol. 2008, 34, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Amaral, R.; Pereira, A.M.; Jacinto, T.; Malinovschi, A.; Janson, C.; Alving, K.; Fonseca, J.A. Comparison of hypothesisand data-driven asthma phenotypes in NHANES 2007–2012: The importance of comprehensive data availability. Clin. Transl. Allergy 2019, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, R.; Bousquet, J.; Pereira, A.M.; Araújo, L.M.; Sá-Sousa, A.; Jacinto, T.; Almeida, R.; Delgado, L.; Fonseca, J.A. Disentangling the heterogeneity of allergic respiratory diseases by latent class analysis reveals novel phenotypes. Allergy 2019, 74, 698–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amelink, M.; De Nijs, S.B.; De Groot, J.C.; Van Tilburg, P.M.B.; Van Spiegel, P.I.; Krouwels, F.H.; Lutter, R.; Zwinderman, A.H.; Weersink, E.J.M.; Brinke, A.T.; et al. Three phenotypes of adult-onset asthma. Allergy 2013, 68, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baptist, A.P.; Hao, W.; Karamched, K.R.; Kaur, B.; Carpenter, L.; Song, P.X. Distinct Asthma Phenotypes Among Older Adults with Asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2018, 6, 244–249.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belhassen, M.; Langlois, C.; Laforest, L.; Dima, A.L.; Ginoux, M.; Sadatsafavi, M.; Van Ganse, E. Level of Asthma Controller Therapy Before Admission to the Hospital. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2016, 4, 877–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bochenek, G.; Kuschill-Dziurda, J.; Szafraniec, K.; Plutecka, H.; Szczeklik, A.; Nizankowska-Mogilnicka, E. Certain subphenotypes of aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease distinguished by latent class analysis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 133, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudier, A.; Curjuric, I.; Basagaña, X.; Hazgui, H.; Anto, J.M.; Bousquet, J.; Bridevaux, P.-O.; Dupuis-Lozeron, E.; Garcia-Aymerich, J.; Heinrich, J.; et al. Ten-Year Follow-up of Cluster-based Asthma Phenotypes in Adults. A Pooled Analysis of Three Cohorts. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 188, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanoine, S.; Pin, I.; Sanchez, M.; Temam, S.; Pison, C.; Le Moual, N.; Severi, G.; Boutron-Ruault, M.-C.; Fournier, A.; Bousquet, J.; et al. Asthma Medication Ratio Phenotypes in Elderly Women. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2018, 6, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Hoffman, E.A.; Wenzel, S.E.; Castro, M.; Fain, S.; Jarjour, N.; Schiebler, M.L.; Chen, K.; Lin, C.-L. Quantitative computed tomographic imaging–based clustering differentiates asthmatic subgroups with distinctive clinical phenotypes. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 140, 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, M.; Stang, J.; Horta, L.; Stensrud, T.; Severo, M.; Mowinckel, P.; Silva, D.; Delgado, L.; Moreira, A.; Carlsen, K.-H. Two distinct phenotypes of asthma in elite athletes identified by latent class analysis. J. Asthma 2015, 52, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deccache, A.; Didier, A.; Mayran, P.; Jeziorski, A.; Rahérison, C. Asthma: Adapting the therapeutic follow-up according to the medical and psychosocial profiles. Rev. Mal. Respir 2018, 35, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Eckert, E.; Fuchs, O.; Kumar, N.; Pekkanen, J.; Dalphin, J.-C.; Riedler, J.; Lauener, R.; Kabesch, M.; Kupczyk, M.; Dahlen, S.-E.; et al. Functional phenotypes determined by fluctuation-based clustering of lung function measurements in healthy and asthmatic cohort participants. Thorax 2017, 73, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fingleton, J.; Travers, J.; Williams, M.; Charles, T.; Bowles, D.; Strik, R.; Shirtcliffe, P.; Weatherall, M.; Beasley, R.; Braithwaite, I.; et al. Treatment responsiveness of phenotypes of symptomatic airways obstruction in adults. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 136, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fingleton, J.; Huang, K.; Weatherall, M.; Guo, Y.; Ivanov, S.; Bruijnzeel, P.; Zhang, H.; Wang, W.; Beasley, R.; Wang, C. Phenotypes of symptomatic airways disease in China and New Zealand. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50, 1700957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haldar, P.; Pavord, I.D.; Shaw, D.E.; Berry, M.A.; Thomas, M.; Brightling, C.E.; Wardlaw, A.J.; Green, R.H. Cluster Analysis and Clinical Asthma Phenotypes. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2008, 178, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, H.-P.; Lin, M.-C.; Wu, C.-C.; Wang, C.-C.; Wang, T.-N. Sex-Specific Asthma Phenotypes, Inflammatory Patterns, and Asthma Control in a Cluster Analysis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2019, 7, 556–567.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilmarinen, P.; Tuomisto, L.E.; Niemelä, O.; Tommola, M.; Haanpää, J.; Kankaanranta, H. Cluster Analysis on Longitudinal Data of Patients with Adult-Onset Asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2017, 5, 967–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, A.S.; Kwon, H.-S.; Cho, Y.S.; Bae, Y.J.; Kim, T.B.; Park, J.S.; Park, S.W.; Uh, S.-T.; Choi, J.-S.; Kim, Y.-H.; et al. Identification of Subtypes of Refractory Asthma in Korean Patients by Cluster Analysis. Lung 2012, 191, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, T.; Verleden, G.; Bergh, O.V.D. Symptoms, Lung Function, and Perception of Asthma Control: An Exploration into the Heterogeneity of the Asthma Control Construct. J. Asthma 2011, 49, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, A.; Imboden, M.; Hansen, S.; Zemp, E.; Bridevaux, P.-O.; Lovison, G.; Schindler, C.; Probst-Hensch, N. Heterogeneity of obesity-asthma association disentangled by latent class analysis, the SAPALDIA cohort. Respir. Med. 2017, 125, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khusial, R.J.; for the ACCURATE Study Group; Sont, J.K.; Loijmans, R.J.B.; Snoeck-Stroband, J.B.; Assendelft, P.J.J.; Schermer, T.R.J.; Honkoop, P.J.; ACCURATE Study Group. Longitudinal outcomes of different asthma phenotypes in primary care, an observational study. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2017, 27, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kim, J.-H.; Chang, H.S.; Shin, S.W.; Baek, D.G.; Son, J.-H.; Park, C.-S.; Park, J.-S. Lung Function Trajectory Types in Never-Smoking Adults with Asthma: Clinical Features and Inflammatory Patterns. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2018, 10, 614–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-A.; Shin, S.-W.; Park, J.-S.; Uh, S.-T.; Chang, H.S.; Bae, D.-J.; Cho, Y.S.; Park, H.-S.; Yoon, H.J.; Choi, B.W.; et al. Clinical Characteristics of Exacerbation-Prone Adult Asthmatics Identified by Cluster Analysis. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2017, 9, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-B.; Jang, A.-S.; Kwon, H.-S.; Park, J.-S.; Chang, Y.-S.; Cho, S.-H.; Choi, B.W.; Park, J.-W.; Nam, D.-H.; Yoon, H.-J.; et al. Identification of asthma clusters in two independent Korean adult asthma cohorts. Eur. Respir. J. 2012, 41, 1308–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kisiel, M.A.; Zhou, X.; Sundh, J.; Ställberg, B.; Lisspers, K.; Malinovschi, A.; Sandelowsky, H.; Montgomery, S.; Nager, A.; Janson, C. Data-driven questionnaire-based cluster analysis of asthma in Swedish adults. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2020, 30, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konno, S.; Taniguchi, N.; Makita, H.; Nakamaru, Y.; Shimizu, K.; Shijubo, N.; Fuke, S.; Takeyabu, K.; Oguri, M.; Kimura, H.; et al. Distinct Phenotypes of Cigarette Smokers Identified by Cluster Analysis of Patients with Severe Asthma. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2015, 12, 1771–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konstantellou, E.; Papaioannou, A.I.; Loukides, S.; Patentalakis, G.; Papaporfyriou, A.; Hillas, G.; Papiris, S.; Koulouris, N.; Bakakos, P.; Kostikas, K. Persistent airflow obstruction in patients with asthma: Characteristics of a distinct clinical phenotype. Respir. Med. 2015, 109, 1404–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labor, M.; Labor, S.; Jurić, I.; Fijačko, V.; Grle, S.P.; Plavec, D. Mood disorders in adult asthma phenotypes. J. Asthma 2017, 55, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Rhee, C.K.; Kim, K.; Kim, J.-A.; Kim, S.H.; Yoo, K.-H.; Kim, W.J.; Park, Y.B.; Park, H.Y.; Jung, K.-S. Identification of subtypes in subjects with mild-to-moderate airflow limitation and its clinical and socioeconomic implications. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2017, 12, 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefaudeux, D.; De Meulder, B.; Loza, M.J.; Peffer, N.; Rowe, A.; Baribaud, F.; Bansal, A.T.; Lutter, R.; Sousa, A.R.; Corfield, J.; et al. U-BIOPRED clinical adult asthma clusters linked to a subset of sputum omics. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 139, 1797–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemiere, C.; Nguyen, S.; Sava, F.; D’Alpaos, V.; Huaux, F.; Vandenplas, O. Occupational asthma phenotypes identified by increased fractional exhaled nitric oxide after exposure to causal agents. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 134, 1063–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkikyrö, E.M.S.; Jaakkola, M.S.; Jaakkola, J.J.K. Subtypes of asthma based on asthma control and severity: A latent class analysis. Respir. Res. 2017, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, W.C.; Meyers, D.A.; Wenzel, S.E.; Teague, W.G.; Li, H.; Li, X.; D’Agostino, R., Jr.; Castro, M.; Curran-Everett, D.; Fitzpatrick, A.M.; et al. Identification of Asthma Phenotypes Using Cluster Analysis in the Severe Asthma Research Program. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2010, 181, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, W.C.; Hastie, A.T.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Busse, W.W.; Jarjour, N.N.; Wenzel, S.E.; Peters, S.P.; Meyers, D.A.; Bleecker, E.R. Sputum neutrophil counts are associated with more severe asthma phenotypes using cluster analysis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 133, 1557–1563.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musk, A.W.; Knuiman, M.; Hunter, M.; Hui, J.; Palmer, L.J.; Beilby, J.; Divitini, M.; Mulrennan, S.; James, A. Patterns of airway disease and the clinical diagnosis of asthma in the Busselton population. Eur. Respir. J. 2011, 38, 1053–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasaki, T.; Matsumoto, H.; Kanemitsu, Y.; Izuhara, K.; Tohda, Y.; Kita, H.; Horiguchi, T.; Kuwabara, K.; Tomii, K.; Otsuka, K.; et al. Integrating longitudinal information on pulmonary function and inflammation using asthma phenotypes. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 133, 1474–1477.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newby, C.; Heaney, L.G.; Menzies-Gow, A.; Niven, R.M.; Mansur, A.; Bucknall, C.; Chaudhuri, R.; Thompson, J.; Burton, P.; Brightling, C.; et al. Statistical Cluster Analysis of the British Thoracic Society Severe Refractory Asthma Registry: Clinical Outcomes and Phenotype Stability. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.H.; Ahn, K.-M.; Chung, S.J.; Shim, J.-S.; Park, H.-W. Usefulness of routine blood test-driven clusters for predicting acute exacerbation in patients with asthma. Respir. Med. 2020, 170, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-W.; Song, W.-J.; Kim, S.-H.; Park, H.-K.; Kim, S.-H.; Kwon, Y.E.; Kwon, H.-S.; Kim, T.-B.; Chang, Y.-S.; Cho, Y.-S.; et al. Classification and implementation of asthma phenotypes in elderly patients. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015, 114, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Baek, S.; Kim, S.; Yoon, S.-Y.; Kwon, H.-S.; Chang, Y.-S.; Cho, Y.S.; Jang, A.-S.; Park, J.W.; Nahm, N.-H.; et al. Clinical Significance of Asthma Clusters by Longitudinal Analysis in Korean Asthma Cohort. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.Y.; Jung, H.W.; Lee, J.M.; Shin, B.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, M.-H.; Song, W.-J.; Kwon, H.-S.; Jung, J.-W.; Kim, S.-H.; et al. Novel Trajectories for Identifying Asthma Phenotypes: A Longitudinal Study in Korean Asthma Cohort, COREA. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pr. 2019, 7, 1850–1857.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, R.; Xie, J.; Chung, K.F.; Li, N.; Yang, Z.; He, M.; Li, J.; Chen, R.; Zhong, N.; Zhang, Q. Asthma Phenotypes Defined from Parameters Obtained During Recovery From a Hospital-Treated Exacerbation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2018, 6, 1960–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakowski, E.; Zhao, S.; Liu, M.; Ahuja, S.; Durmus, N.; Grunig, G.; De Lafaille, M.C.; Wu, Y.; Reibman, J. Variability of blood eosinophils in patients in a clinic for severe asthma. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2018, 49, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rootmensen, G.; Van Keimpema, A.; Zwinderman, A.; Sterk, P. Clinical phenotypes of obstructive airway diseases in an outpatient population. J. Asthma 2016, 53, 1026–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakagami, T.; Hasegawa, T.; Koya, T.; Furukawa, T.; Kawakami, H.; Kimura, Y.; Hoshino, Y.; Sakamoto, H.; Shima, K.; Kagamu, H.; et al. Cluster analysis identifies characteristic phenotypes of asthma with accelerated lung function decline. J. Asthma 2013, 51, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schatz, M.; Hsu, J.-W.Y.; Zeiger, R.S.; Chen, W.; Dorenbaum, A.; Chipps, B.E.; Haselkorn, T. Phenotypes determined by cluster analysis in severe or difficult-to-treat asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 133, 1549–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seino, Y.; Hasegawa, T.; Koya, T.; Sakagami, T.; Mashima, I.; Shimizu, N.; Muramatsu, Y.; Muramatsu, K.; Suzuki, E.; Kikuchi, T.; et al. A Cluster Analysis of Bronchial Asthma Patients with Depressive Symptoms. Intern. Med. 2018, 57, 1967–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiya, K.; Nakatani, E.; Fukutomi, Y.; Kaneda, H.; Iikura, M.; Yoshida, M.; Takahashi, K.; Tomii, K.; Nishikawa, M.; Kaneko, N.; et al. Severe or life-threatening asthma exacerbation: Patient heterogeneity identified by cluster analysis. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2016, 46, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendín-Hernández, M.P.; Ávila-Zarza, C.; Sanz, C.; García-Sánchez, A.; Marcos-Vadillo, E.; Muñoz-Bellido, F.J.; Laffond, E.; Domingo, C.; Isidoro-García, M.; Dávila, I. Cluster Analysis Identifies 3 Phenotypes within Allergic Asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2018, 6, 955–961.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Pariente, J.; Rodrigo, G.; Fiz, J.A.; Crespo, A.; Plaza, V.; the High Risk Asthma Research Group. Identification and characterization of near-fatal asthma phenotypes by cluster analysis. Allergy 2015, 70, 1139–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siroux, V.; Basagaña, X.; Boudier, A.; Pin, I.; Garcia-Aymerich, J.; Vesin, A.; Slama, R.; Jarvis, D.; Anto, J.M.; Kauffmann, F.; et al. Identifying adult asthma phenotypes using a clustering approach. Eur. Respir. J. 2011, 38, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, E.R.; Goleva, E.; King, T.S.; Lehman, E.; Stevens, A.D.; Jackson, L.P.; Stream, A.R.; Fahy, J.V. Cluster Analysis of Obesity and Asthma Phenotypes. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H.; Nakatani, E.; Fukutomi, Y.; Sekiya, K.; Kaneda, H.; Iikura, M.; Yoshida, M.; Takahashi, K.; Tomii, K.; Nishikawa, M.; et al. Identification of patterns of factors preceding severe or life-threatening asthma exacerbations in a nationwide study. Allergy 2018, 73, 1110–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay, T.R.; Choo, X.N.; Yii, A.; Chung, K.F.; Chan, Y.H.; Wong, H.S.; Chan, A.; Tee, A.; Koh, M.S. Asthma phenotypes in a multi-ethnic Asian cohort. Respir. Med. 2019, 157, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Molen, T.; Fletcher, M.; Price, D. Identifying Patient Attitudinal Clusters Associated with Asthma Control: The European REALISE Survey. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2018, 6, 962–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Liang, R.; Zhou, T.; Zheng, J.; Liang, B.M.; Zhang, H.P.; Luo, F.M.; Gibson, P.G.; Wang, G. Identification and validation of asthma phenotypes in Chinese population using cluster analysis. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017, 119, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherall, M.; Travers, J.; Shirtcliffe, P.M.; Marsh, S.E.; Williams, M.V.; Nowitz, M.R.; Aldington, S.; Beasley, R. Distinct clinical phenotypes of airways disease defined by cluster analysis. Eur. Respir. J. 2009, 34, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Bleier, B.S.; Li, L.; Zhan, X.; Zhang, L.; Lv, Q.; Wang, J.; Wei, Y. Clinical Phenotypes of Nasal Polyps and Comorbid Asthma Based on Cluster Analysis of Disease History. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2018, 6, 1297–1305.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.-J.; Xu, W.-G.; Guo, X.-J.; Han, F.-F.; Peng, J.; Li, X.-M.; Guan, W.-B.; Yu, L.-W.; Sun, J.-Y.; Cui, Z.-L.; et al. Differences in airway remodeling and airway inflammation among moderate-severe asthma clinical phenotypes. J. Thorac. Dis. 2017, 9, 2904–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youroukova, V.M.; Dimitrova, D.G.; Valerieva, A.D.; Lesichkova, S.S.; Velikova, T.V.; Ivanova-Todorova, E.I.; Tumangelova-Yuzeir, K.D. Phenotypes Determined by Cluster Analysis in Moderate to Severe Bronchial Asthma. Folia Med. 2017, 59, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Zaihra, T.; Walsh, C.J.; Ahmed, S.; Fugère, C.; Hamid, Q.A.; Olivenstein, R.; Martin, J.G.; Benedetti, A. Phenotyping of difficult asthma using longitudinal physiological and biomarker measurements reveals significant differences in stability between clusters. BMC Pulm. Med. 2016, 16, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuschieri, S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2019, 13, S31–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, S.E. Asthma phenotypes: The evolution from clinical to molecular approaches. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Database | Research Query |

|---|---|

| Pubmed | (phenotyp*[Title/Abstract] OR cluster*[Title/Abstract]) AND (“Asthma”[MeSH] OR asthm*[Title/Abstract]) AND (“Adult”[MeSH] OR “Adult” [Title/Abstract] OR adult*[ Title/Abstract] OR “Middle Aged”[Mesh:NoExp] OR “Aged”[Mesh:NoExp]) AND (humans[mesh:noexp] NOT animals[mesh:noexp]) NOT ((Review[ptyp] OR Meta-Analysis[ptyp] OR Letter[ptyp] OR Case Reports[ptyp])) |

| Scopus | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (asthm*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ((phenotyp* OR cluster*)) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ((adult* OR “middle aged” OR elderly))) AND (EXCLUDE (DOCTYPE, “re”) OR EXCLUDE (DOCTYPE, “le”) OR EXCLUDE (DOCTYPE, “ed”) OR EXCLUDE (DOCTYPE, “no”) OR EXCLUDE (DOCTYPE, “ch”) OR EXCLUDE (DOCTYPE, “sh”)) |

| Web of Science | (TS = (asthm*) AND TS = ((phenotyp* OR cluster*)) AND TS = ((adult* OR middle aged or elderly))) NOT DT = (BOOK CHAPTER OR REVIEW OR EDITORIAL MATERIAL OR NOTE OR LETTER) |

| Domain | Variables |

|---|---|

| Personal | Gender, age, smoking, BMI, family history of asthma, race, education level, socioeconomic status |

| Functional | FEV1, FVC, FEV1/FVC, KCO or other lung function measurements, reversibility of obstruction, bronchial hyperresponsiveness |

| Clinical | Symptoms, exacerbations, asthma control, asthma severity scores, activity limitation, age of onset, disease duration, work-related asthma, near-fatal episode, associated comorbidities, imaging-related |

| Atopy | Atopic status, serum IgE, sensitization, allergen exposure, rhinitis or other allergic diseases, skin prick test, immunotherapy |

| Inflammatory | FeNO, blood eosinophils, and neutrophils, sputum eosinophils, and neutrophils, hsCRP |

| Medication | Regular medication, daily dose of prednisolone or equivalent, use of rescue bronchodilator, oral corticosteroid use |

| Healthcare use | Emergency department use, hospitalizations, stays in ICU, unscheduled visits to GP |

| Behavioral | Attitude towards the disease, perception of control, observed behavior, psychological status, confidence in doctor, stress in daily life, impact on activities in daily life |

| Study ID (Author, Year) | Setting, Design | Inclusion Criteria in the Analysis | Number of Patients Included in the Analysis | Age | Patients’ Characteristics | Variables Used for Cluster Analysis (Number and Domains) | Method Used for Cluster Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agache, 2018 [17] | Single center (Romania), cross-sectional | Diagnosis of seasonal allergic rhinitis and asthma | 57 | 34.12 ± 10.59 | Intermittent asthma: 35 (8 were uncontrolled); Persistent asthma: 22 (10 were uncontrolled) | 11 variables: personal, atopy | K-means Cluster Analysis |

| Alves, 2008 [18] | Single center (Brazil), cohort | Diagnosis of severe asthma, treatment-compliant | 88 | 56 ± 12 | Female: 73%; ICS in high dose: 67%; OCS: 30%; LABA: 88% | 12 variables: personal, functional, clinical, atopy | Factor Analysis |

| Amaral, 2019 [19] | Population-based (NHANES—USA), cross-sectional | Adults (≥18 years) with current asthma | 1059 | N.A. | N.A. | 4 variables in Model 1, 9 variables in Model 2: personal, clinical, inflammatory, health care use | Latent Class Analysis |

| Amaral, 2019 [20] | Population-based (ICAR—Portugal), cross-sectional | Adults (≥18 years) with and without self-reported asthma and/or rhinitis | 728 | 43.9 ± 15.2 | Female: 63% female; Non-smokers: 61%; ICS: 11% | 19 variables: personal, functional, clinical, atopy, inflammatory | Latent Class Analysis |

| Amelink, 2013 [21] | Multicenter (Netherlands), cross-sectional | Adults (20–75 years), diagnosis of asthma after the age of 18, medication stability | 200 | 53.9 ± 10.8 | Female: 60.5%; Severe asthma: 38.5% | 35 variables: personal, functional, clinical | K-means Cluster Analysis |

| Baptist, 2018 [22] | Multicenter (USA), cross-sectional | Age ≥ 55 years, with persistent asthma | 180 | 65.9 ± 7.4 | Male: 26.1%; Late-onset (after the age of 40): 46.7% | 24 variables: personal, functional, clinical, atopy, medication | Hierarchical Cluster Analysis |

| Belhassen, 2016 [23] | Population-based (France), cohort | ≥3 dispensations for asthma-related medication (2006–2014), aged 6–40 at third dispensation, hospitalization ≥12 months after the entry date | 275 | 19.0 ± 11.7 | Female: 47.3% female; Long-term disease status: 12.4% | 3 variables: clinical (treatment) | Hierarchical Cluster Analysis |

| Bhargava, 2019 [15] | Single center (India), cohort | Asthma treated at primary and secondary care levels only with intermittent oral bronchodilators and steroids, and nebulization during the acute attacks, ≥6 months of follow-up, and ≥4 spirometry tests | 100 | 33.4 ± 19.72 | 55% female; Asthma control according to GINA: 32% controlled, 19% partially controlled, 49% uncontrolled | N.A. | Hierarchical Cluster Analysis |

| Bochenek, 2014 [24] | Single center (Poland), cross-sectional | Diagnosis of aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease | 201 | 49.4 ± 12.4 | Female: 66.6%; Intermittent asthma: 18.9%; Mild persistent asthma: 15.9%; Moderate persistent asthma: 34.8%; Severe persistent asthma: 30.3% | 12 variables: personal, functional, clinical, atopy, inflammatory | Latent Class Analysis |

| Boudier, 2013 [25] | Population-based (ECHRS, SAPALDIA and EGEA studies), cohort | Adults, report of ever asthma | 3320 | 35.8 ± 9.8 | Female: 66.0%; Prevalence of BHR: 44.8% and 40.6% at baseline and follow-up, respectively | 9 variables: functional, clinical, atopy, medication | Latent Transition Analysis//Expectation-maximization |

| Chanoine, 2017 [26] | Asthma-E3N study in France, nested case–control | All women who reported having ever had asthma at least once between 1992 and 2008 | 4328 | 69.6 ± 6.1 | All female; Patients on maintenance therapy: 899 (13.6% with low controller-to-total asthma medication ratio) | Medication (8-year fluctuations of controller-to-total asthma medication ratio) | Latent Class Analysis |

| Choi, 2017 [27] | Multicenter (3 different imaging centers in the USA), cross-sectional | Diagnosis of asthma | 248 | NSA: 36.0 ± 12.2 SA: 46.9 ± 13.1 | Nonsevere asthma: 106 (64% female); Severe asthma: 142 (63% female) | 57 variables: clinical (CT imaging) | K-means Cluster Analysis |

| Couto, 2015 [28] | Multicenter (databases of elite athletes in Portugal and Norway), cross-sectional | Diagnosis of asthma according to criteria set by the Internal Olympic Committee to document asthma in athletes | 150 | 25 (14–40) | Male: 71%; 91 Portuguese and 59 Norwegian | 9 variables: functional, clinical, atopy, inflammatory, medication | Latent Class Analysis |

| Deccache, 2018 [29] | REALISE survey of adult asthma patients in 11 European countries, cross-sectional | French survey respondents | 1024 | 34.8 | Female: 66%; Active smokers: 26%; Asthma control (GINA): 17% controlled, 35% partially controlled, 48% uncontrolled | 3 variables: behavioural | K-means Cluster Analysis |

| Delgado-Eckert, 2018 [30] | Multicenter (BIOAIR study in Europe), cohort | Diagnosis of asthma | 45 (after data analysis of 138 patients) | - | Severe asthma: 76; Mild-to-moderate asthma: 62 | 2 variables: functional | Hierarchical Cluster Analysis |

| Fingleton, 2015 [31] | Cross-sectional | Symptoms of wheeze and breathlessness in the last 12 months | 452 | 18 to 75 | N.A. | 13 variables: personal, functional, clinical, inflammatory | Hierarchical Cluster Analysis |

| Fingleton, 2017 [32] | Cross-sectional | Symptoms of wheeze and breathlessness in the last 12 months | 345 | 55.9 ± 8.7 | Male: 45.5% | 12 variables: personal, functional, clinical, inflammatory | Hierarchical Cluster Analysis |

| Gupta, 2010 [16] | Single center (UK), cross-sectional | Severe asthma, measurable right upper lobe apical segmental bronchus, and sufficient baseline data | 99 | N.A. | N.A. | Unspecified (representative variables identified on factor analysis) | K-means Cluster Analysis |

| Haldar, 2008 [33] | Single center (UK), cross-sectional First dataset: primary-care Second dataset: secondary care, refractory asthma | Diagnosis of asthma and sufficient symptoms to warrant at least one prescription for asthma therapy in the previous 12 months | 371 Primary care: 184 Secondary care: 187 | Primary care: 49.2 ± 13.9 Secondary care: 43.4 ± 15.9 | Female: primary care—54.4%; secondary care—65.8% | Functional, clinical, inflammatory, behavioral, | Two-step Cluster Analysis |

| Hsiao, 2019 [34] | Single center (Taiwan), cross-sectional | Older than 20 years, diagnosis of asthma | 720 | 53.63 ± 17.22 | Female: 58.47% | 8 variables: personal, functional, atopy, inflammatory | Two-step Cluster Analysis |

| Ilmarinen, 2017 [35] | Single center (Finland), cohort | Diagnosis of asthma | 171 | N.A. | Female: 58.5%; Nonatopic: 63.5% | 15 variables: personal, functional, clinical, atopy, inflammatory | Two-step Cluster Analysis |

| Jang, 2013 [36] | Multicenter (tertiary referral hospitals, Korea), cohort | Refractory asthma (ATS criteria) | 86 | 39.9 ± 17.3 | Female: 61.6% | 5 variables: personal, functional | Two-step Cluster Analysis |

| Janssens, 2012 [37] | Multicenter (Belgium), Cross-sectional Two subsamples: university students, secondary care outpatient respiratory clinic | Student subsample: physician-diagnosed asthma and familiarity with asthma reliever medication; Outpatient clinic subsample: diagnosed with asthma for at least 6 months, with lung function measurement, and no other pulmonary obstructive disease | 94 Student subsample: 32; Outpatient clinic subsample: 62 | 37.87 ± 18.56 | Female: 54.26% female; Intermittent asthma: 10.64%; Mild persistent asthma: 30.85%; Moderate persistent asthma: 53.19%; Severe persistent asthma: 4.26% | 6 variables: functional, clinical, medication, behavioral | Latent Transition Analysis//Expectation-maximization |

| Jeong, 2017 [38] | Population-based (SAPALDIA—Switzerland), cohort | Ever asthma | 959 | N.A. | N.A. | 7 variables: personal, clinical, atopy, medication | Latent Class Analysis |

| Khusial, 2017 [39] | Multicenter (ACCURATE trial), randomized clinical trial | Adult asthmatics, 18–50 years old, treated in primary care, with one-year follow-up | 611 | 39.4 ± 9.1 | Female: 68.4%; Exacerbations in the past 12 months: 0.67 per patient | 14 variables: personal, functional, clinical, atopy, inflammatory, medication | Hierarchical Cluster Analysis |

| Kim, 2018 [40] | Korean Asthma Database cohort | Non-smoking asthmatics, presence of reversible airway obstruction, airway hyperreactivity, or improvement in FEV1 >20% after 2 weeks of treatment with corticosteroids | 1679 with imputed data (448 with complete data) | N.A. | N.A. | 5 variables: functional (longitudinal levels of post-bronchodilator FEV1) | Two-step Cluster Analysis |

| Kim, 2017 [41] | Multicenter (Korea), cohort | Diagnosis of asthma, regular follow-up for over 1 year | 259 | 56 (18–88) | Female: 81.5% | 12 variables: personal, functional, atopy, infammatory | Two-step Cluster Analysis |

| Kim, 2013 [42] | Multicenter (Korea), two cohorts (COREA and SCH) | Asthma, ethnic Koreans, >18 years, regular follow-up and appropriate medications (GINA) | 2567 COREA: 724; SCH: 4 | N.A. | N.A. | 6 variables: personal, functional, health care use | Two-step Cluster Analysis |

| Kisiel, 2020 [43] | Swedish cohort | Diagnosis of asthma | 1291 | 54.3 ± 15.5 | Female: 61.4% | 14 variables: personal, clinical, atopy | K-medoids Cluster Analysis |

| Konno, 2015 [44] | Multicenter (Japan), cohort | Diagnosis of severe asthma (ATS criteria) for at least 1 year, ≥16 years | 127 | 58.0 ± 13.1 | Female: 59.8%; Onset age: 38.2 ± 17.7; AQLQ: 5.38 (4.79–6.21) | 12 variables: personal, functional, atopy, inflammatory | Hierarchical Cluster Analysis |

| Konstantellou, 2015 [45] | Single center (Greece), cohort | Adult asthmatics, optimally treated for at least 6 months and adherent to therapy | 170 | N.A. | Persistent airflow obstruction: 35.3% (71.1% of which with criteria for severe refractory asthma vs. 4.5% in the non-persistent group) | 4 variables: clinical, atopy, medication | Two-step Cluster Analysis |

| Labor, 2018 [46] | Single center (tertiary hospital pulmonology outpatient clinic, Croatia), cross-sectional | Physician diagnosis of asthma (GINA) at least a year before the start of the study | 201 | 38 (26–51) | Female: 62.5% | 11 variables: personal, functional, clinical, atopy | Two-step Cluster Analysis |

| Lee, 2017 [47] | Population-based (KNAHES and NHI claims, Korea) | Age ≥20 years and acceptable spirometry, FEV1/FVC <0.7 and FEV1 ≥60% predicted | 2140 | 63.7 ± 11.7 | Female: 29%; Under any respiratory medicine: 17.1% | 6 variables: personal, functional, clinical | K-means Cluster Analysis |

| Lefaudeux, 2017 [48] | U-BIOPRED cohort | Diagnosis of asthma | 418 (266 in training set, 152 in validation set) | N.A. | N.A: | 8 variables: personal, functional, clinical, medication | K-medoids Cluster Analysis |

| Lemiere, 2014 [49] | Single center (tertiary center, Canada), cohort (2006–2012) | Subjects investigated for possible occupational asthma with a positive specific inhalation challenge | 73 | 40.05 ± 10.3 | Male: 61.2% | 6 variables: personal, atopy, inflammatory, medication | Two-step Cluster Analysis |

| Loureiro, 2015 [8] | Single center (outpatient clinic, Portugal), cross-sectional | Asthmatics, age between 18 and 79 years | 57 | 45.6 ± 18.0 | Female: 73.7%; Severe exacerbation (previous year): 52.6%; Severe asthma (WHO): 57.9% | 22 variables: personal, functional, clinical, atopy, inflammatory, medication | Hierarchical Cluster Analysis |

| Loza, 2016 [9] | ADEPT and U-BIOPRED studies, cross-sectional and cohort | Diagnosis of asthma | 156 | N.A. | N.A. | 9 variables: functional, clinical, inflammatory | K-medoids Cluster Analysis |

| Makikyro, 2017 [50] | Population-based (Northern Finnish Asthma Study), cross-sectional | Adults 17–73 years old who had asthma and lived in Northern Finland, diagnosis of asthma according to the criteria of The Social Insurance Institution of Finland | 1995 | <30: 212 30–59: 1268 ≥60: 515 | Female: 65.3% | 5 variables: medication, health care use; 5 covariates: personal, clinical, atopy | Latent Class Analysis |

| Moore, 2010 [51] | Multicenter (USA), Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP) cohort | Nonsmoking asthmatics who met the ATS definition of severe asthma, older than 12 years of age | 726 | 37 ± 14 | Female: 66% | 34 variables: personal, functional, clinical, atopy, medication, health care use | Hierarchical Cluster Analysis |

| Moore, 2014 [52] | Multicenter (USA), Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP) cohort | Nonsmoking asthmatics with severe or mild-to-moderate disease | 423 (severe—126; not severe—297) | Severe: 41 ± 14; Not severe: 34 ± 13 | Female: severe—56%; not severe—66% | 15 variables: personal, functional, inflammatory, medication, health care use | Factor Analysis |

| Musk, 2011 [53] | Random sample from the electoral register for the district of Busselton, Western Australia, cross-sectional | Adults | 1969 | 54 ± 17 | Female: 50.6%; Reported “doctor-diagnosed asthma”: 18%; Reported wheeze: 24%; Reported “doctor-diagnosed bronchitis”: 20%; Atopic: ~50%; Never smoked: 51% | 10 variables: personal, functional, atopy, inflammatory | K-means Cluster Analysis |

| Nagasaki, 2014 [54] | Multicenter (Japan), | Adult patients with stable asthma, receiving ICS therapy for at least 4 years and had undergone at least 3 pulmonary function tests | 224 | 62.3 ± 13.7 | Male/female: 53/171; FEV1 measurements: 16.26 ± 13.9; Follow-up period: 8.0 ± 4.5 years | 7 variables: personal, functional, clinical, atopy, inflammatory | Hierarchical Cluster Analysis |

| Newby, 2014 [55] | Multicenter (British Thoracic Society Severe refractory Asthma Registry), cohort | Diagnosis of asthma, at least 1 year of follow-up | 349 | 21 ± 18 | Female: 63.6% | 23 variables: personal, functional, clinical, atopy, inflammatory, medication, health care use | Two-step Cluster Analysis |

| Oh, 2020 [56] | Single center (Korea), cohort | Diagnosis of asthma | 590 | N.A. | N.A. | Clinical, inflammatory (routine blood test results at enrollment) | K-means Cluster Analysis |

| Park, 2015 [57] | Multicenter (Korea), primary cohort; Secondary cohort to assess generalizability (COREA) | Patients 65 years or older with asthma, regular medication, and controlled status (GINA) | 1301 Primary Cohort: 872 Secondary Cohort: 429 | 75.1 ± 5.5 (in primary cohort) | Female: 52.8% (in primary cohort) | 9 variables: personal, functional, clinical, atopy | K-means Cluster Analysis |

| Park, 2013 [58] | Multicenter (patients from the COREA cohort, Korea), cohort | Diagnosis of asthma, followed up every 3 months | 724 | N.A. | N.A. | 6 variables: personal, functional, atopy, health care use | K-means Cluster Analysis |

| Park, 2019 [59] | Multicenter (patients from the COREA cohort, Korea), cohort | Diagnosis of asthma, followed up every 3 months | 486 | N.A. | N.A. | Functional, clinical | Latent Mixture Modeling |

| Qiu, 2018 [60] | Single center (Guangzhou Institute of Respiratory Disease, China), cross-sectional | Patients aged 18–65 years with respiratory symptoms that required hospitalization; Classified as severe asthma exacerbation (requirement of a course of OCS) | 218 | 47.43 ± 13.56 | Female 57.3% | 21 variables: personal, functional, clinical, inflammatory | Hierarchical Cluster Analysis |

| Rakowski, 2019 [61] | Single center (NYU/Bellevue Hospital Asthma Clinic, USA), cohort | Adults with a primary diagnosis of asthma who had undergone a visit at the center within a 3-month period | 219 | 59.2 ± 16 | Female: 22% | Inflammatory (distribution of blood eosinophil levels) | K-means Cluster Analysis |

| Rootmensen, 2016 [62] | Single center (pulmonary outpatient clinic, Netherlands), cross-sectional | Over 18 years, diagnosis of asthma or COPD by pulmonary physicians, understood Dutch sufficiently to answer the questionnaires, never had consulted a pulmonary nurse | 191 | 61 ± 15 | Female: 43%; Diagnosed as having COPD: 58%; Diagnosed as having asthma: 42% | 8 variables: personal, functional, atopy, inflammatory | K-means Cluster Analysis |

| Sakagami, 2014 [63] | Single center (outpatients of Niigata University Hospital, Japan), cohort | Diagnosis of bronchial asthma; available history of lung function and pharmacology, never-smokers | 86 | 59.8 ± 13.2 | Female/Male: 47/39 | 7 variables: personal, functional, atopy | Hierarchical Cluster Analysis |

| Schatz, 2014 [64] | TENOR: multicenter, prospective cohort (2001–2004) | Severe or difficult-to-treat asthma, ages 6 years or older | 3612 | N.A. | Female: 66.5% | 8 variables: personal, functional, clinical, atopy | Hierarchical Cluster Analysis |

| Seino, 2018 [65] | Single center (outpatients of Niigata University Hospital, Japan), cross-sectional | Diagnosis of asthma, ≥16 years of age, depressive symptom-positive | 128 | 63 (44.8–76) | Female: 65.6% | 9 variables: personal, clinical, medication | Hierarchical Cluster Analysis |

| Sekiya, 2016 [66] | Multicenter (Japan), cross-sectional | >16 years old; hospitalization for severe or life-threatening asthma exacerbation, not complicated by pneumonia, atelectasis, or pneumothorax; SpO2 <90% on room air before treatment | 175 | 57 ± 18 | Female: 66%; Asthma severity: 34% intermittent, 18% mild persistent, 25% moderate persistent, 23% severe persistent | 24 variables: personal, clinical, atopy, medication, health care use | K-medoids Cluster Analysis |

| Sendín-Hernández, 2018 [67] | Single center (Spain), cohort | Age over 14 years, asthma diagnosed following GEMA 2009, at least 1 positive skin prick test, symptoms and signs of asthma concordant with allergen exposure | 225 | 39.56 | Female: 57.3%; Mean FENO: 48.84 ppb | 19 variables: personal, functional, clinical, atopy, inflammatory, medication | Hierarchical Cluster Analysis |

| Serrano-Pariente, 2015 [68] | Multicenter (Multicentric Life-Threatening Asthma Study—MLTAS, Spain), prospective cohort | Asthmatics ≥15 years with near-fatal asthma episode | 84 | 51.5 ± 19.9 | Female: 60%; Asthma severity (GINA): 2% intermittent, 2% mild persistent, 41% moderate persistent, 55% severe persistent | 44 variables: personal, clinical, medication, health care use | Two-step Cluster Analysis |

| Siroux, 2011 [69] | Multicenter, cross-sectional EGEA: French case–control and family based study; ECHRS: Population-based cohort with an 8-year follow-up | Ever asthma | 2446 EGEA2 sample: 1805; ECRHSII sample: 641 | EGEA2 sample: 60% ≥40; ECRHSII sample: 44% ≥40 | Female: EGEA2 sample—59%, ECRHSII sample—47% | 14 variables: personal, functional, clinical, atopy | Latent Class Analysis |

| Sutherland, 2012 [70] | Multicenter (patients participating in the common run-in period of the TALC and BASALT trials), cohort | Adults (≥18 years of age) with persistent asthma, nonsmoking status | 250 | 37.6 ± 12.5 | Female: 68% | 20 variables: personal, functional, clinical, inflammatory | Hierarchical Cluster Analysis |

| Tanaka, 2018 [71] | Multicenter (Japan), cohort | >16 years of age, requiring hospitalization due to severe or life-threatening asthma attacks with SpO2 < 90%; no heart failure, pneumonia, pneumothorax, or other pulmonary diseases on X-ray | 190 | N.A. | N.A. | Clinical | K-means Cluster Analysis |

| Tay, 2019 [72] | Multicenter (2 databases, Singapore), cohort | Diagnosis of asthma | 420 | 52 ± 18 | Female: 52.9% | 9 variables: personal, functional, clinical, inflammatory | K-means Cluster Analysis |

| van der Molen, 2018 [73] | Multicenter (REALISE Europe survey), cross-sectional | Aged 18 to 50 years old, physician-confirmed asthma diagnosis, at least 2 asthma prescriptions in the last 2 years, used social media | 7930 | 18–25: 19.2%; 26–35: 33.6%; 36–40: 17.2%; 41–50: 30.0% | Female: 61.7%; Diagnosed with asthma at least 11 years ago: 70.7%; Controlled, partially controlled, or uncontrolled asthma: 20.2%, 35.0%, and 44.8%, respectively | 8 summary factors: behavioural | Latent Class Analysis |

| Wang, 2017 [74] | Single center (China), 12- month cohort Post hoc analysis of cohort study, which consisted of 2 parts (cross-sectional survey, prospective nonintervention cohort) | Diagnosis of asthma according to ATS and GINA criteria based on current episode symptoms, physician’s diagnosis, airway hyperresponsiveness, or at least 12% improvement in FEV1 after bronchodilator | 284 | 39.1 ± 12.1 | Female: 62%; Severe asthma (GINA): 9.9% | 10 variables: personal, functional, clinical, atopy, behavioral | Two-step Cluster Analysis |

| Weatherall, 2009 [75] | Wellington Respiratory Survey (New Zealand), cross-sectional | Pre-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC <0.7 and/or reporting wheeze within the last 12 months | 175 | 57.4 ± 13.5 | Pre-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC <0.7 alone: 41.2%, Reported wheeze within the last 12 months: 34.4%, Met both criteria: 24.4% | 9 variables: personal, functional, atopy, inflammatory | Hierarchical Cluster Analysis |

| Wu, 2018 [76] | Multicenter (China), prospective cohort | Nasal polyps and comorbid asthma, 16 to 68 years of age | 110 | 47.45 ± 10.08 | Female: 36.36%; Adult-onset asthma: 70.91%; Patients with NPcA had prior sinus surgery: 64.55% | 12 variables: personal, clinical, atopy | Two-step Cluster Analysis |

| Wu, 2014 [10] | Severe Asthma Research Program, cohort | Diagnosis of asthma | 378 | N.A. | N.A. | 112 variables clustered into 10 categories: personal, functional, clinical, atopy, inflammatory, medication, health care use | K-means Cluster Analysis |

| Ye, 2017 [77] | Single center (patients hospitalized by asthma exacerbation at the XinHua Hospital, China), cross-sectional | Asthma diagnosed according to GINA, aged 12–80 years | 120 | 55 (34–63) | Female: 49.3%; Health care utilization in the last year: 8.9% hospitalized for asthma, 18.2% emergency for asthma, 42.9% outpatient, 30.0% none | 21 variables: personal, functional, clinical, atopy, inflammatory, medication, health care use | Hierarchical Cluster Analysis |

| Youroukova, 2017 [78] | Bulgaria, cross-sectional | Moderate to severe bronchial asthma, on maintenance therapy in the last four weeks, age ≥18 years | 40 | 46.37 ± 14.77 | Female: 65% | 16 variables: personal, functional, clinical, atopy, inflammatory | Hierarchical Cluster Analysis |

| Zaihra, 2016 [79] | Difficult asthma cohort (Montreal Chest Institute of the McGill University Health Centre, Canada) | Subjects aged 18–80 years with moderate or severe asthma (ATS criteria) | 125 (48 moderate asthmatics and 77 severe asthmatics) | Moderate asthmatics: 46.6 ± 11.2; Severe asthmatics: 49.9 ± 12.6 | Female: moderate asthmatics—48%, severe asthmatics—56% | Personal, functional, clinical, inflammatory | K-means Cluster Analysis |

| Study ID (Author, Year) | Defining Variables of Phenotypes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Comorbidities | Onset | Severity | Symptoms, Treatment | Lung Function | Atopy | Inflammation | Others | |

| Hierarchical Cluster Analysis | |||||||||

| Baptist, 2018 [22] | Late | ||||||||

| Mild | |||||||||

| Atopic | |||||||||

| Severe | |||||||||

| Belhassen, 2016 [23] | Less medication | ||||||||

| Fixed dose inhalers | |||||||||

| Free combination | |||||||||

| Bhargava, 2019 [15] | Childhood | Mild | Preserved | Atopic | |||||

| Male | Overweight | Adolescent | Severe | Atopic | |||||

| Female | Obese | Late | Severe | Least atop. | |||||

| Female | Obese | Young age | Mild | Atopic | |||||

| Delgado-Eckert, 2018 [30] | Mild/Mod. | ||||||||

| Severe | |||||||||

| Fingleton, 2015 [31] | Mod./Severe | Atopic | |||||||

| COPD | |||||||||

| Obese | |||||||||

| Mild | Atopic | ||||||||

| Mild | Intermittent | ||||||||

| Fingleton, 2017 [32] | COPD | Late | Severe | ||||||

| COPD | Early | ||||||||

| Atopic | |||||||||

| Adult | Nonatopic | ||||||||

| Early | Mild | Intermittent | Atopic | ||||||

| Khusial, 2017 [39] | Early | Atopic | |||||||

| Female | Late | ||||||||

| Reversible | |||||||||

| Smokers | |||||||||

| Exacerbators | |||||||||

| Konno, 2015 [44] | Early | Atopic | Mild eos | ||||||

| Smokers | Late | Fixed limitation | Intense Th2 | ||||||

| Smokers | Late | Fixed limitation | Low Th2 | ||||||

| Nonsmokers | Late | Low Th2 | |||||||

| Female | Nonsmokers, high BMI | Late | Intense Th2 | ||||||

| Loureiro, 2015 [8] | Early | Mild | Allergic | Eosinophilic | |||||

| Female | Moderate | Long evolution | Allergic | Mixed | |||||

| Female, young | Early | Brittle | Allergic | No evidence | |||||

| Female | Obese | Late | Severe | Highly sympt. | Mixed | ||||

| Late | Severe | Long evolution | Chronic obstruction | Eosinophilic | |||||

| Moore, 2010 [51] | Female, young | Childhood | Normal | Atopic | |||||

| Female, slightly older | Childhood | Atopic | |||||||

| Female, older | |||||||||

| Childhood | Severe | Atopic | |||||||

| Female | Late | Less atopy | |||||||

| Nagasaki, 2014 [54] | Late | Nonatopic | Paucigranulocytic | ||||||

| Early | Atopic | ||||||||

| Late | Eosinophilic | ||||||||

| Poor control | Low FEV1 | Mixed granulocytic | |||||||

| Qiu, 2018 [60] | Female | Early | Small degree of obstruction | Sputum neutrophilia | |||||

| Female | Nonsmokers | Severe airflow obstruction | High sputum eosinophilia | ||||||

| Female | Moderate reduction of FEV1 | Sputum neutrophilia | |||||||

| Male | Smokers | Severe airflow obstruction | High sputum eosinophilia | ||||||

| Sakagami, 2014 [63] | Female | Low IgE | |||||||

| Young | Early | Atopic | |||||||

| Older | Late | Less atopic | |||||||

| Schatz, 2014 [64] | Female, white | Adult | Low IgE | ||||||

| Atopy | |||||||||

| Male | |||||||||

| Nonwhite | |||||||||

| Aspirin sensitivity | |||||||||

| Seino, 2018 [65] | Elderly | Severe | Poor control | Adherence barriers | |||||

| Elderly | Low BMI | Severe | Poor control | No adherence barriers | |||||

| Younger | High BMI | Not severe | Controlled | No adherence barriers | |||||

| Sendín-Hernández, 2018 [67] | Mild | Intermittent | Low IgE | Without family history | |||||

| Mild | Intermediate IgE | With family history | |||||||

| Mod./Severe | Needs CS and LABA | High IgE | With family history | ||||||

| Sutherland, 2012 [70] | Female | Nonobese | |||||||

| Male | Nonobese | ||||||||

| Obese | Uncontrolled | ||||||||

| Obese | Controlled | ||||||||

| Weatherall, 2009 [75] | Severe | Chronic bronchitis + emphysema | Variable obstruction | Atopic | |||||

| Emphysema | |||||||||

| Atopic | Eosinophilic | ||||||||

| Mild obstruction | No other features | ||||||||

| Nonsmokers | Chronic bronchitis | ||||||||

| Ye, 2017 [77] | Early | Atopic | |||||||

| Moderate | Atopic | ||||||||

| Late | Nonatopic | ||||||||

| Fixed obstruction | |||||||||

| Youroukova, 2017 [78] | Late | Impaired | Nonatopic | ||||||

| Smokers | Late | High sympt., exacerbations | |||||||

| Aspirin sensitivity | Late | Symptomatic | Eosinophilic | ||||||

| Early | Atopic | ||||||||

| K-means Cluster Analysis | |||||||||

| Agache, 2010 [17] | Severe rhinitis | Polysensitization | |||||||

| Male | Severe rhinitis | Exposure to pets | |||||||

| High IgE, polysensit. | |||||||||

| Amelink, 2013 [21] | Severe | Persistent limitation | Eosinophilic | ||||||

| Female | Obese | Symptomatic | Low sputum eos | High health care use | |||||

| Mild/Mod. | Controlled | Normal | |||||||

| Choi, 2017 [27] | Normal airway, increased lung deformation | ||||||||

| Luminal narrowing, reduced lung deformation | |||||||||

| Wall thickening | |||||||||

| Luminal narrowing, increase in air trapping, decreased lung deformation | |||||||||

| Deccache, 2018 [29] | Confident | ||||||||

| Committed | |||||||||

| Questing | |||||||||

| Concerned | |||||||||

| Gupta, 2010 [16] | Severe | Concordant control score | Eosinophilic | Greater bronchodilator response | |||||

| Female | High BMI | Severe | High control score | Low eos | |||||

| Severe | High control score | Low eos | |||||||

| Severe | Low control score | Eosinophilic | |||||||

| Lee, 2017 [47] | Near-normal | ||||||||

| Asthma | |||||||||

| COPD | |||||||||

| Asthmatic-overlap | |||||||||

| COPD-overlap | |||||||||

| Musk, 2011 [53] | Male normal | ||||||||

| Female normal | |||||||||

| Female | Obese | ||||||||

| Younger | Atopic | ||||||||

| Male | Atopic | High eNO | |||||||

| Male | Poor FEV1 | Atopic | |||||||

| BHR | Atopic | ||||||||

| Oh, 2020 [56] | High UA, T. Chol., AST, ALT, and hsCRP | High eos | |||||||

| Intermediate | |||||||||

| Low UA, T. Chol. and T. Bili. | |||||||||

| Park, 2015 [57] | Long duration | Marked obstruction | |||||||

| Female | Normal | ||||||||

| Male | Smokers | Reduced | |||||||

| High BMI | Borderline | ||||||||

| Park, 2013 [58] | Smokers | ||||||||

| Severe | Obstructive | ||||||||

| Early | Atopic | ||||||||

| Late | Mild | ||||||||

| Rakowski, 2019 [61] | Low eos | ||||||||

| Intermediate eos | |||||||||

| High eos | |||||||||

| Rootmensen, 2016 [62] | COPD without emphysema | ||||||||

| COPD with emphysema | |||||||||

| Allergic | |||||||||

| Overlap with COPD | Atopic | ||||||||

| Tanaka, 2018 [71] | Young to middle-aged | Rapid exacerbation | Hypersensitive | ||||||

| Middle-aged and older | Fairly rapid exacerbation, low dyspnea | ||||||||

| Smokers | Slow exacerbation, high dyspnea, chronic daily mild/mod. sympt. | ||||||||

| Tay, 2019 [72] | Female, Chinese | Late | Best control | ||||||

| Female, non-Chinese | Obesity | Worst control | |||||||

| Multi-ethnic | Atopic | ||||||||

| Wu, 2014 [10] | Healthy control subjects | ||||||||

| Mild | |||||||||

| Severe | Frequent, low AQLQ scores | High sensitization | |||||||

| Early | Low | Allergic | Eosinophilic | ||||||

| Nasal polyps | Late | Severe | Eosinophilic | ||||||

| Sinusitis | Early | Severe | The most symptoms | Lowest | Frequent health care use | ||||

| Zaihra, 2016 [79] | Late | Severe | |||||||

| Female | High BMI | Severe | |||||||

| Early | Severe | Reduced | Atopic | ||||||

| Moderate | Good | ||||||||

| Two-step Cluster Analysis | |||||||||

| Haldar, 2008 [33] | Early | Atopic | Primary care | ||||||

| Obese | Noneosinophilic | Primary care | |||||||

| Benign | Primary care | ||||||||

| Early | Atopic | Secondary care | |||||||

| Obese | Noneosinophilic | Secondary care | |||||||

| Early | Symptomatic | Minimal eos | Secondary care | ||||||

| Late | Few symptoms | Eosinophilic | Secondary care | ||||||

| Hsiao, 2019 [34] | Female | Normal BMI | Late | Normal | Nonatopic | Low neutrophils, low eos | |||

| Female, young adults | High eos, low neutrophils | ||||||||

| Female | Obese | Late | Low IgE | High neutrophils, low eos | |||||

| Male | Normal BMI | Late | Normal | Low IgE | Low eos | ||||

| Male, young adults | Current smokers | Atopic | High eos | ||||||

| Male | Ex-smokers | Late | High eos | ||||||

| Ilmarinen, 2017 [35] | Nonrhinitic | ||||||||

| Smokers | |||||||||

| Female | |||||||||

| Obese | |||||||||

| Adult | Early | Atopic | |||||||

| Jang, 2013 [36] | Younger | Nonrhinitic | Well-preserved | Atopic | Eosinophilic | ||||

| Younger | Severe | Low IgE | Highest total sputum cells, low eos | ||||||

| Female | Nonsmokers | High BHR | High number of sputum cells | ||||||

| Male | Smokers | Low | |||||||

| Kim, 2018 [40] | Female, middle-to-old aged | High BMI | Mild | ||||||

| Female, younger | Mild | Atopic | |||||||

| Early | Mild | Mild decrease | |||||||

| Severe | Atopic | Eosinophilic | |||||||

| Severe | Persistent obstruction | Less atopic | Neutrophilic | ||||||

| Kim, 2017 [41] | Early | Preserved | Atopic | ||||||

| Late | Impaired | Nonatopic | |||||||

| Early | Severely impaired | Atopic | |||||||

| Late | Well-preserved | Nonatopic | |||||||

| Kim, 2013 [42] | Smokers | ||||||||

| Severe | Obstructive | ||||||||

| Early | Atopic | ||||||||

| Late | Mild | ||||||||

| Konstantellou, 2015 [45] | Without high-dose ICS and OCS | Not related to persistent obstruction | Nonatopic | ||||||

| High-dose ICS and OCS | Persistent obstruction | Atopic | |||||||

| Without high-dose ICS and OCS | Not related to persistent obstruction | Atopic | |||||||

| Labor, 2017 [46] | Allergic | ||||||||

| Aspirin sensitivity | |||||||||

| Late | |||||||||

| Obese | |||||||||

| Respiratory infections | |||||||||

| Lemiere, 2014 [49] | No subjects taking ICS | Normal | Atopic | Exposure to HMW agents | |||||

| Taking ICS | Lower | Atopic | |||||||

| Taking ICS | Lower | Less atopic | Only exposed to low molecular weight agents | ||||||

| Newby, 2014 [55] | Early | Atopic | |||||||

| Obese | Late | ||||||||

| Least severe | Normal | ||||||||

| Late | Eosinophilic | ||||||||

| Obstruction | |||||||||

| Serrano-Pariente, 2015 [68] | Older | Severe | |||||||

| Respiratory arrest, impaired consciousness level | Mechanical ventilation | ||||||||

| Younger | Insufficient anti-inflammatory treatment | Sensistization to Alternaria alternate and soybean | |||||||

| Wang, 2017 [74] | Male | Mild | Low exacerbation risk | Slight obstruction | |||||

| Allergic | |||||||||

| Female | Mild | Low exacerbation risk | Slight obstruction | ||||||

| Smokers | Fixed limitation | ||||||||

| Low socioeconomic status | |||||||||

| Wu, 2018 [76] | Nasal polyps | Atopic | |||||||

| Nasal polyps, Smokers | |||||||||

| Older | Nasal polyps | ||||||||

| K-medoids Cluster Analysis | |||||||||

| Kisiel, 2020 [43] | Female | Early | |||||||

| Female | Adult | ||||||||

| Male | Adult | ||||||||

| Lefaudeux, 2017 [48] | Mod./Severe | Well-controlled | |||||||

| High BMI, smokers | Late | Severe | OCS use | Obstruction | |||||

| Severe | OCS use | Obstruction | |||||||

| Female | High BMI | Severe | Frequent exacerbations, OCS use | ||||||

| Loza, 2016 [9] | Early | Mild | Normal | Low | |||||

| Moderate | Mild reversible obstruction, BHR | Atopic | Eosinophilic | ||||||

| Mixed severity | Mild reversible obstruction | Neutrophilic | |||||||

| Severe | Uncontrolled | Severe reversible obstruction | Mixed granulocytic | ||||||

| Sekiya, 2016 [66] | Younger | Severe | |||||||

| Female, elderly | |||||||||

| Without baseline ICS treatment | Allergic | ||||||||

| Male, elderly | COPD | ||||||||

| No baseline sympt, | |||||||||

| Latent Class Analysis | |||||||||

| Amaral, 2019 [19] | Highly symptomatic | Better | |||||||

| Less symptomatic | Poor | ||||||||

| Amaral, 2019 [20] | Low probability of sympt. | Nonallergic | |||||||

| Nasal sympt. (very high), ocular sympt. (moderate) | |||||||||

| Nasal, and ocular sympt. (high) | Allergic | ||||||||

| No bronchial sympt. | Allergic | ||||||||

| Nasal, bronchial, and ocular sympt. (very high) with severe nasal impairment | Nonallergic | ||||||||

| Presence of bronchial sympt. | Allergic | ||||||||

| Bochenek, 2014 [24] | Moderate | Intensive | |||||||

| Mild | Well-controlled | Low health care use | |||||||

| Severe | Poorly controlled, severe exacerbations | Obstruction | |||||||

| Female | Poorly controlled, frequent and severe exacerbations | ||||||||

| Chanoine, 2018 [26] | Never regularly maintenance therapy | ||||||||

| Persistent high controller-to-total medication | |||||||||

| Increasing controller-to-total medication | |||||||||

| Initiating treatment | |||||||||

| Treatment discontinuation | |||||||||

| Couto, 2018 [28] | Atopic | ||||||||

| Sports | |||||||||

| Jeong, 2017 [38] | Persistent, multiple sympt. | ||||||||

| Symptomatic | |||||||||

| Symptom-free | Atopic | ||||||||

| Symptom-free | Nonatopic | ||||||||

| Makikyro, 2017 [50] | Female | Mild | Controlled | ||||||

| Female | Moderate | Partially controlled | |||||||

| Female | Unknown | Uncontrolled | |||||||

| Female | Severe | Uncontrolled | |||||||

| Male | Mild | Controlled | |||||||

| Male | Unknown | Uncontrolled | |||||||

| Male | Severe | Partially controlled | |||||||

| Siroux, 2011 [69] | Childhood | Active, treated | Allergic | ||||||

| Adult | Active, treated | ||||||||

| Mild | Inactive, untreated | Allergic | |||||||

| Adult | Mild | Inactive, untreated | |||||||

| van der Molen, 2018 [73] | Confident, self-managing | ||||||||

| Confident, accepting | |||||||||

| Confident, dependent | |||||||||

| Concerned, confident | |||||||||

| Not confident | |||||||||

| Factor Analysis | |||||||||

| Alves, 2008 [18] | Treatment-resistant, more nocturnal sympt. and exacerbations | ||||||||

| Older | Longer duration | Persistent limitation, lower FEV1/FVC | |||||||

| Rhinosinusit is, nonsmokers | Reversible obstruction | Allergic | |||||||

| Aspirin intolerance | Near-fatal episodes | ||||||||

| Moore, 2014 [52] | Early | Mild/Mod. | Paucigranulocytic or eosinophilic sputum | ||||||

| Early | Mild/Mod. | OCS use | Paucigranulocytic or eosinophilic sputum | ||||||

| Mod./Severe | High doses of CS | Normal | Frequent health care use | ||||||

| Mod./Severe | High doses of CS | Reduced | Frequent health care use | ||||||

| Latent Transition Analysis//Expectation-maximization | |||||||||

| Boudier, 2013 [25] | Few sympt., no treatment | Allergic | |||||||

| Few sympt., no treatment | Nonallergic | ||||||||

| High sympt., treatment | Nonallergic | ||||||||

| High sympt, treatment | BHR | Allergic | |||||||

| Moderate sympt. | BHR | Allergic | |||||||

| Moderate sympt. | Normal | Allergic | |||||||

| Moderate sympt., no treatment | Nonallergic | ||||||||

| Janssens, 2012 [37] | Well-controlled | ||||||||

| Intermediate control | |||||||||

| Poorly controlled | |||||||||

| Latent Mixture Modeling | |||||||||

| Park, 2019 [59] | Male, older | Smokers | Less atopic | ||||||

| Smokers | Higher IgE | ||||||||

| Younger | More atopic | ||||||||

| Female | Nonsmokers | ||||||||

| Study ID (Author, Year) | Confounding | Selection of Patients | Classification of Interventions | Deviations from Intended Interventions | Missing Data | Measurement of Outcomes | Selections of Reported Results | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agache, 2018 [17] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Alves, 2008 [18] | 0 | - | + | + | + | + | + | - |

| Amaral, 2019 [19] | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | 0 |

| Amaral, 2019 [20] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Amelink, 2013 [21] | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 0 |

| Baptist, 2018 [22] | - | - | + | + | + | + | + | - |

| Belhassen, 2016 [23] | -- | -- | - | + | - | + | + | -- |

| Bhargava, 2019 [15] | - | 0 | - | + | + | + | + | - |

| Bochenek, 2014 [24] | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 0 |

| Boudier, 2013 [25] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Chanoine, 2017 [26] | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | - |

| Choi, 2017 [27] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Couto, 2015 [28] | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | - |

| Deccache, 2018 [29] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Delgado-Eckert, 2018 [30] | -- | -- | - | 0 | - | 0 | - | -- |

| Fingleton, 2015 [31] | 0 | - | + | + | 0 | + | + | - |

| Fingleton, 2017 [32] | 0 | - | + | + | 0 | + | + | - |

| Gupta, 2010 [16] | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | 0 |

| Haldar, 2008 [33] | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 0 |

| Hsiao, 2019 [34] | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 0 |

| Ilmarinen, 2017 [35] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Jang, 2013 [36] | 0 | 0 | + | + | 0 | + | + | 0 |

| Janssens, 2012 [37] | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 0 |

| Jeong, 2017 [38] | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 0 |

| Khusial, 2017 [39] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Kim, 2018 [40] | 0 | 0 | + | + | 0 | + | + | 0 |

| Kim, 2017 [41] | - | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | - |

| Kim, 2013 [42] | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | - |

| Kisiel, 2020 [43] | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 0 |

| Konno, 2015 [44] | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | 0 |

| Konstantellou, 2015 [45] | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | 0 |

| Labor, 2018 [46] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Lee, 2017 [47] | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 0 |

| Lefaudeux, 2017 [48] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Lemiere, 2014 [49] | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | 0 |

| Loureiro, 2015 [8] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Loza, 2016 [9] | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 0 |

| Makikyro, 2017 [50] | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 0 |

| Moore, 2010 [51] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Moore, 2014 [52] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Musk, 2011 [53] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Nagasaki, 2014 [54] | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 0 |

| Newby, 2014 [55] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Oh, 2020 [56] | - | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | - |

| Park, 2015 [57] | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 0 |

| Park, 2013 [58] | 0 | + | + | + | 0 | + | + | 0 |

| Park, 2019 [59] | -- | + | + | + | + | + | + | -- |

| Qiu, 2018 [60] | - | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | - |

| Rakowski, 2019 [61] | - | + | - | + | + | + | + | - |

| Rootmensen, 2016 [62] | + | + | + | 0 | + | + | + | 0 |

| Sakagami, 2014 [63] | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | 0 |

| Schatz, 2014 [64] | 0 | + | + | 0 | + | + | + | 0 |

| Seino, 2018 [65] | 0 | + | + | 0 | + | + | + | 0 |

| Sekiya, 2016 [66] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Sendín-Hernández, 2018 [67] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Serrano-Pariente, 2015 [68] | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 0 |

| Siroux, 2011 [69] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Sutherland, 2012 [70] | + | + | + | + | 0 | + | + | 0 |

| Tanaka, 2018 [71] | 0 | + | - | + | 0 | + | + | - |

| Tay, 2019 [72] | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 0 |

| van der Molen, 2018 [73] | - | + | + | + | + | - | + | - |

| Wang, 2017 [74] | 0 | + | 0 | + | + | + | + | 0 |

| Weatherall, 2009 [75] | 0 | + | + | + | 0 | + | + | 0 |

| Wu, 2018 [76] | - | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | - |

| Wu, 2014 [10] | + | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | 0 |

| Ye, 2017 [77] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Youroukova, 2017 [78] | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | - |

| Zaihra, 2016 [79] | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cunha, F.; Amaral, R.; Jacinto, T.; Sousa-Pinto, B.; Fonseca, J.A. A Systematic Review of Asthma Phenotypes Derived by Data-Driven Methods. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 644. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11040644

Cunha F, Amaral R, Jacinto T, Sousa-Pinto B, Fonseca JA. A Systematic Review of Asthma Phenotypes Derived by Data-Driven Methods. Diagnostics. 2021; 11(4):644. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11040644

Chicago/Turabian StyleCunha, Francisco, Rita Amaral, Tiago Jacinto, Bernardo Sousa-Pinto, and João A. Fonseca. 2021. "A Systematic Review of Asthma Phenotypes Derived by Data-Driven Methods" Diagnostics 11, no. 4: 644. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11040644

APA StyleCunha, F., Amaral, R., Jacinto, T., Sousa-Pinto, B., & Fonseca, J. A. (2021). A Systematic Review of Asthma Phenotypes Derived by Data-Driven Methods. Diagnostics, 11(4), 644. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11040644