Abstract

MODY2 is caused by heterozygous inactivating mutations in the glucokinase (GCK) gene that result in persistent, stable and mild fasting hyperglycaemia (5.6–8.0 mmol/L, glycosylated haemoglobin range of 5.6–7.3%). Patients with GCK mutations usually do not require any drug treatment, except during pregnancy. The GCK gene is considered to be responsible for about 20% of all MODY cases, transcription factors for 67% and other genes for 13% of the cases. Based on our findings, GCK and HNF1A mutations together are responsible for about 90% of the cases in Hungary, this ratio being higher than the 70% reported in the literature. More than 70% of these patients have a mutation in the GCK gene, this means that GCK-MODY is the most prevalent form of MODY in Hungary. In the 91 index patients and their 72 family members examined, we have identified a total of 65 different pathogenic (18) and likely pathogenic (47) GCK mutations of which 28 were novel. In two families, de novo GCK mutations were detected. About 30% of the GCK-MODY patients examined were receiving unnecessary OAD or insulin therapy at the time of requesting their genetic testing, therefore the importance of having a molecular genetic diagnosis can lead to a major improvement in their quality of life.

1. Introduction

1.1. GCK-MODY (MODY2)

MODY2 is caused by heterozygous inactivating mutations in the glucokinase (GCK) gene encoding a key regulator glycolytic enzyme of the hexokinase family [1]. It has two tissue-specific promoters and a different exon 1, the upstream promoter being functional in the pancreas (exon 1a) and brain, while the downstream one only in the liver (exons 1b and 1c), resulting in different isoforms of the GCK gene [2,3].

GCK has an important role in carbohydrate metabolism. It is responsible for the catalysis of the first reaction of the glycolytic pathway, the glucose phosphorylation [1]. GCK acts as a glucose sensor of the pancreatic beta-cells [1], therefore it is critical in the process of the regulation of insulin secretion and release.

In the case of GCK-MODY, a mildly elevated glucose level is caused by heterozygous loss-of-function mutations in the GCK gene. Any of the 10 exons and promoter of the pancreatic isoform of the GCK gene might be affected as no mutational hotspots have been identified. The mutations might affect enzyme kinetics or protein folding [4,5]. To date, almost 800 disease-causing small scale GCK mutations have been reported in the professional version of the HGMD (Human Gene Mutation Database, version 2021.1) associated with the MODY phenotype, the majority of them being missense alterations resulting in abnormal structure and/or function of the mutant protein, often affecting its kinetic parameters.

GCK gene mutations result in abnormal glucose sensing, raising the threshold of glucose-mediated insulin secretion. As a consequence, stable and mild fasting hyperglycaemia (5.6–8.0 mmol/L, glycosylated haemoglobin range of 5.6–7.3%) persists that does not deteriorate with age and is not associated with an increased risk of complications [6,7]. The clinical manifestation of GCK-MODY is generally nonprogressive, usually asymptomatic in childhood. The elevated glucose level is present from birth, therefore it is mostly detected incidentally [8,9]. Performing an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) can help to distinguish GCK-MODY patients from other types of MODY as in the case of GCK-MODY, patients generally have a small (<3.5 mmol/L) 2 h glucose increment [10].

Patients with GCK mutations usually do not require any drug treatment (except during pregnancy or in critical clinical situations), however, they often receive unnecessary insulin therapy or oral antidiabetic drug treatment [9]. Good glycaemic control can usually be achieved with only diet and exercise [11].

1.2. MODY Prevalence

The estimated MODY prevalence is around 1–5% of all diabetes mellitus cases, but it varies depending on the population studied [12,13]. The GCK gene is considered to be responsible for about 20% of all MODY cases, transcription factors for 67% and other genes for 13% of the cases [14]. GCK and HNF1A genes together are responsible for about 70% of all known MODY cases, the ratio of the two genes widely varying between countries [15]. For example in the United Kingdom, the prevalence of GCK-MODY is reported to be 32% [6,16], and 63% in the case of HNF1A-MODY [17]. The Norwegian MODY Registry reports a distribution of 53% HNF1A-MODY, 30% GCK-MODY, 7.5% HNF4A-MODY and 5.6% HNF1B-MODY [18]. A Polish study reports GCK-MODY to be the most prevalent with 83% [19] while the American SEARCH study reports HNF1A-MODY as the most prevalent form with roughly 60%, GCK-MODY being in the second position with 30% [20].

2. Materials and Methods

As this paper is Part II of two accompanying publications in the Journal, the patients and methods presented in this section are the same as the ones described in Part I of this article. The genes tested and genetic methods used during the study are presented in the Supplementary file (Part I of these articles).

2.1. Patients

A total of 450 unrelated index patients with suspected MODY diagnosis and their 202 family members have been referred to our laboratory for genetic testing from all around Hungary. All participants or their guardians have given informed consent to genetic testing according to national regulations.

2.2. Methods

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood leukocytes using the QIAamp Blood Mini kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany).

In the case of 102 index patients, Sanger sequencing of the GCK, HNF1A or HNF4A genes was performed using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Bidirectional pyrosequencing with a minimum coverage of 40× was performed on Roche GS Junior 454 pyrosequencing system (Roche 454 Life Sciences, Branford, CT, USA) in the case of 33 index patients.

The 311 index patient samples were sequenced on Illumina Miseq or NextSeq 550 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) sequencer systems in 2 × 150 cycle (or 2 × 250 cycle in the case of the MODY MASTR kit) paired-end mode. Three different library preparation methods were used before sequencing. The MODY MASTR kit (Multiplicom, Niel, Belgium) was used to examine 7 genes in the case of 76 index patients. A custom-made and enrichment-based DNA library preparation kit (Qiagen, GmbH, Hilden, Germany) containing 17 genes was used in the case of 164 index patients, and another custom-designed gene panel (Twist Bioscience, South San Francisco, CA, USA) was used, examining 18 genes in the case of 69, and 20 genes in the case of 6 index patients. (Supplementary Table S1, see Part I) In the case of Illumina sequenced data, data analysis was performed using the NextGene software (SoftGenetics, State College, PA, USA).

MLPA (multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification) was performed in the case of 32 index patients (as a single test in the case of 4 index patients and in addition to one of the above-mentioned methods in the case of 28 index patients) using SALSA MLPA Probemix P241 MODY Mix 1 and/or SALSA MLPA Probemix P357 MODY Mix 2 (MRC Holland, Amsterdam, Netherlands) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

The testing method(s) used in the case of every index patient is described in the Supplementary Table S2 (Part I of these articles).

Cascade testing was performed in 202 family members usually by targeted Sanger sequencing of the respective exon of the MODY-causing gene in which their relative had a possibly pathogenic mutation.

2.3. Variant Confirmation

All variants obtained with next-generation sequencing that were suspected to be disease-causing were validated by Sanger sequencing. Furthermore, when the amplicon’s minimum coverage was <40× in the NGS data, the respective exons were also sequenced using the Sanger method.

2.4. Variant Filtering and Interpretation

All detected variants having a MAF > 0.01 (minor allele frequency) in the gnomAD population database were filtered. The remaining variants were classified according to the ACMG standards and guidelines [21,22]. A web-based interpretation tool, Franklin (Genoox) [23] was used to assist the classification. HGMD Professional and ClinVar databases were also used in variant interpretation.

2.5. Clinical Data Collection

Clinical data of patients and family members having a ‘pathogenic’ (‘P’) or ‘likely pathogenic’ (‘LP’) mutation in one of the MODY-causing genes was collected from their application form sent and filled out by their clinician at the time of requesting the genetic testing. The MODY probability calculator (https://www.diabetesgenes.org/, accessed on 20 March 2021) was used to calculate the probability of the patient having MODY when all the information required was available and the patient was under the age of 35, as the calculator cannot be used in case of patients older than that.

3. Results

GCK Mutations

From the 450 index patients examined, 132 tested positive for a pathogenic or likely pathogenic classified variant in one of the MODY-causing genes with a total of 89 mutations. GCK and HNF1A mutations together were responsible for about 90% of the cases, this ratio being higher in Hungary than the 70% reported in the literature [15]. More than 70% (65/89) of the mutations among the index patients were found in the GCK gene (Table 1). With targeted cascade testing of family members, we identified an additional 95 positive cases, resulting in a total of 227 patients with a molecular genetic diagnosis of MODY. More than 70% of these patients have a mutation in the GCK gene, which means that GCK-MODY is the most prevalent form of MODY in Hungary.

Table 1.

Number of patients harbouring a pathogenic/likely pathogenic mutation in one of the MODY-causing genes.

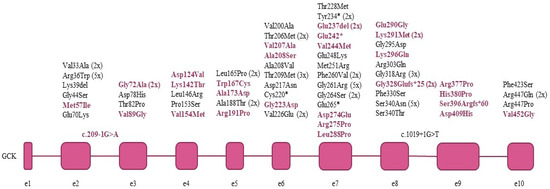

In the 91 index patients and their 72 family members, we have identified a total of 65 different pathogenic (18) and likely pathogenic (47) GCK mutations, summarized in Table 2 and Figure 1. Every mutation detected was in heterozygous form. Eighteen mutations were found in more than one apparently unrelated families, the most frequent ones being p.Arg36Trp (5 families), p.Gly261Arg (G > A 5 families and G > C 1 family) and p.Ser340Asn (5 families). Of the detected mutations, 40% (28/65) are novel, while 60% (37/65) have been previously described in the literature. Almost 85% (55/65) of the detected GCK mutations were missense mutations resulting in an amino acid change. In addition, four such mutations were found at exon/intron boundaries of the coding sequence, possibly disrupting exon splicing as well (Table 3).

Table 2.

Pathogenic (18) and likely pathogenic (47) mutations in the GCK gene.

Figure 1.

GCK mutations detected in the index patients. Novel mutations are shown in colour.

Table 3.

GCK mutations distributed by the amino acid consequence.

In the case of two families (F101, F173), the p.Ala188Thr and p.Val226Glu mutations were both detected and co-segregated in the proband and her parent, suggesting a cis position.

Table 4 presents the clinical data of the index patients and their family members. Obesity is not characteristic of these patients, only about 10% of them have their BMI out of the range considered healthy. The age of diagnosis differs widely among the patients, and they have generally received their molecular genetic diagnosis of MODY several years after their diagnosis of diabetes. We had information regarding their treatment in 125 cases. Almost half of the patients examined do not receive any treatment or control their blood sugar levels only by maintaining a healthy diet, which is in accordance with the literature. However, around 10% of these patients receive unnecessary insulin treatment and another 16% are on some oral antidiabetic drug, also unnecessary (Table 5). Their HbA1c levels are generally around 7.0% or lower.

Table 4.

Clinical data of patients with GCK mutation.

Table 5.

The distribution of the types of therapy received before proper genetic diagnosis.

The detected GCK mutation was shown to be de novo in two cases (Table 4, F041 and F375).

We had enough information to use the MODY calculator in about half of the patients. In the case of about three-quarters of these patients (62/81), the calculator showed a 75.5% probability of the patient having MODY, this was the highest probability we could get using the calculator.

4. Discussion

Two hundred and twenty-seven patients were diagnosed with MODY in our examined cohort from all over Hungary in about 10 years with a 70% mutation rate in the GCK gene, meaning that the most prevalent form of monogenic diabetes in Hungary is the GCK-MODY.

Although GCK-MODY patients generally do not need any treatment, around 30% of the patients examined were receiving an unnecessary OAD or insulin therapy. We would like to emphasize once again the importance of having a proper molecular genetic diagnosis, as this can lead to a major improvement in the patients’ quality of life by stopping their drug treatment.

The majority of the examined patients had an HbA1c level of 7.0% or lower, this being in accordance with the mildly elevated level reported in the literature and in contrast with the HNF1A patients we examined, where about 60% of the patients had a value of 7.0% or above.

As two families had de novo GCK mutations, one criterion of MODY about the transgenerational occurrence of the disease should be treated with caution—the lack of apparent inheritance pattern does not exclude the possibility of having a MODY.

The effect of the pathogenic and likely pathogenic mutations on the kinetics of the glucokinase enzyme is still not precisely known in many cases, therefore we plan to further investigate this question in the future.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/life11080771/s1, Table S1. The list of genes examined with the different library preparation kits; Table S2. Methods used for testing the index patients; Table S3. Clinical data of patients with HNF1A mutation; Table S4. Clinical data of patients having a mutation in other MODY-causing genes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization of the study, I.B. and Z.G.; methodology, Z.S. and L.M.; clinical data analysis, Z.G., I.K., A.L., P.T.-H., O.B., E.F., and Z.K.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.S.; writing—review and editing, all authors; funding acquisition, Z.G., I.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by OTKA K109076 and Ministry of National Economy, Hungary GINOP-2.3.2-15-2016-00039 (to I.B.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Patients gave informed written consent. The laboratory is approved by the National Public Health and Medical Officer Service (approval number: 094025024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Part of the data of this paper is being presented on the 60th National Congress of the Hungarian Society of Laboratory Medicine Online Congress, 26–28 August 2021.

References

- Osbak, K.K.; Colclough, K.; Saint-Martin, C.; Beer, N.L.; Bellanné-Chantelot, C.; Ellard, S.; Gloyn, A.L. Update on Mutations in Glucokinase (GCK), Which Cause Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young, Permanent Neonatal Diabetes, and Hyperinsulinemic Hypoglycemia. Hum. Mutat. 2009, 30, 1512–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iynedjian, P.B. Mammalian Glucokinase and Its Gene. Biochem. J. 1993, 293, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnuson, M.A. Glucokinase Gene Structure: Functional Implications of Molecular Genetic Studies. Diabetes 1990, 39, 523–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capuano, M.; Garcia-Herrero, C.M.; Tinto, N.; Carluccio, C.; Capobianco, V.; Coto, I.; Cola, A.; Iafusco, D.; Franzese, A.; Zagari, A.; et al. Glucokinase (GCK) Mutations and Their Characterization in MODY2 Children of Southern Italy. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negahdar, M.; Aukrust, I.; Molnes, J.; Solheim, M.H.; Johansson, B.B.; Sagen, J.V.; Dahl-Jørgensen, K.; Kulkarni, R.N.; Søvik, O.; Flatmark, T.; et al. GCK-MODY Diabetes as a Protein Misfolding Disease: The Mutation R275C Promotes Protein Misfolding, Self-Association and Cellular Degradation. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2014, 382, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, K.M. Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young: Update and Perspectives on Diagnosis and Treatment. Yeungnam Univ. J. Med. 2020, 37, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, A.M.; Wensley, K.J.; Ellard, S.; Murphy, R.; Shepherd, M.; Colclough, K.; Hattersley, A.T.; Shields, B.M. Use of HbA1c in the Identification of Patients with Hyperglycaemia Caused by a Glucokinase Mutation: Observational Case Control Studies. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaoglan, M.; Nacarkahya, G. Clinical and Laboratory Clues of Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young and Determination of Association with Molecular Diagnosis. J. Diabetes 2021, 13, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, T.J.; Ellard, S. Maturity Onset Diabetes of the Young: Identification and Diagnosis. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2013, 50, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentínová, L.; Beer, N.L.; Staník, J.; Tribble, N.D.; van de Bunt, M.; Hučková, M.; Barrett, A.; Klimeš, I.; Gašperíková, D.; Gloyn, A.L. Identification and Functional Characterisation of Novel Glucokinase Mutations Causing Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young in Slovakia. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xie, Z.; Sun, X.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Luo, S.; Huang, G.; Li, X.; Xia, Y.; Zhou, Z. A New Screening Strategy and Whole-Exome Sequencing for the Early Diagnosis of Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2021, 37, e3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, S.C.; Neves, J.S.; Pérez, A.; Carvalho, D. Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young: From a Molecular Basis Perspective toward the Clinical Phenotype and Proper Management. Endocrinol. Diabetes Nutr. 2020, 67, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, B.M.; Shepherd, M.; Hudson, M.; McDonald, T.J.; Colclough, K.; Peters, J.; Knight, B.; Hyde, C.; Ellard, S.; Pearson, E.R.; et al. Population-Based Assessment of a Biomarker-Based Screening Pathway to Aid Diagnosis of Monogenic Diabetes in Young-Onset Patients. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firdous, P.; Nissar, K.; Ali, S.; Ganai, B.A.; Shabir, U.; Hassan, T.; Masoodi, S.R. Genetic Testing of Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young Current Status and Future Perspectives. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellard, S.; Bellanné-Chantelot, C.; Hattersley, A.T. European Molecular Genetics Quality Network (EMQN) MODY group Best Practice Guidelines for the Molecular Genetic Diagnosis of Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young. Diabetologia 2008, 51, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkonge, K.M.; Nkonge, D.K.; Nkonge, T.N. The Epidemiology, Molecular Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young (MODY). Clin. Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eide, S.A.; Raeder, H.; Johansson, S.; Midthjell, K.; Søvik, O.; Njølstad, P.R.; Molven, A. Prevalence of HNF1A (MODY3) Mutations in a Norwegian Population (the HUNT2 Study). Diabet. Med. J. Br. Diabet. Assoc. 2008, 25, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, B.B.; Irgens, K.U.; Molnes, J.; Sztromwasser, P.; Aukrust, I.; Juliusson, P.B.; Søvik, O.; Levy, S.; Skrivarhaug, T.; Joner, G.; et al. Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing Reveals MODY in up to 6.5% of Antibody-Negative Diabetes Cases Listed in the Norwegian Childhood Diabetes Registry. Diabetologia 2016, 60, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fendler, W.; Borowiec, M.; Baranowska-Jazwiecka, A.; Szadkowska, A.; Skala-Zamorowska, E.; Deja, G.; Jarosz-Chobot, P.; Techmanska, I.; Bautembach-Minkowska, J.; Mysliwiec, M.; et al. Prevalence of Monogenic Diabetes amongst Polish Children after a Nationwide Genetic Screening Campaign. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 2631–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pihoker, C.; Gilliam, L.K.; Ellard, S.; Dabelea, D.; Davis, C.; Dolan, L.M.; Greenbaum, C.J.; Imperatore, G.; Lawrence, J.M.; Marcovina, S.M.; et al. Prevalence, Characteristics and Clinical Diagnosis of Maturity Onset Diabetes of the Young Due to Mutations in HNF1A, HNF4A, and Glucokinase: Results from the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, 4055–4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, C.S.; Bale, S.; Bellissimo, D.B.; Das, S.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.R.; Lyon, E.; Ward, B.E. Molecular Subcommittee of the ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee ACMG Recommendations for Standards for Interpretation and Reporting of Sequence Variations: Revisions 2007. Genet. Med. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 2008, 10, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence Variants: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Einhorn, Y.; Einhorn, M.; Kamshov, A.; Lev, O.; Trabelsi, A.; Paz-Yaacov, N.; Gross, S.J. Gene-Specific Artificial Intelligence-Based Variant Classification Engine: Results of a Time-Capsule Experiment. Preprint 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukásová, P.; Vcelák, J.; Vanková, M.; Vejrazková, D.; Andelová, K.; Bendlová, B. Screening of Mutations and Polymorphisms in the Glucokinase Gene in Czech Diabetic and Healthy Control Populations. Physiol. Res. 2008, 57 (Suppl. 1), S99–S108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hager, J.; Blanché, H.; Sun, F.; Vaxillaire, N.V.; Poller, W.; Cohen, D.; Czernichow, P.; Velho, G.; Robert, J.J.; Cohen, N. Six Mutations in the Glucokinase Gene Identified in MODY by Using a Nonradioactive Sensitive Screening Technique. Diabetes 1994, 43, 730–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prisco, F.; Iafusco, D.; Franzese, A.; Sulli, N.; Barbetti, F. MODY 2 Presenting as Neonatal Hyperglycaemia: A Need to Reshape the Definition of “Neonatal Diabetes”? Diabetologia 2000, 43, 1331–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gragnoli, C.; Cockburn, B.N.; Chiaramonte, F.; Gorini, A.; Marietti, G.; Marozzi, G.; Signorini, A.M. Early-Onset Type II Diabetes Mellitus in Italian Families Due to Mutations in the Genes Encoding Hepatic Nuclear Factor 1 Alpha and Glucokinase. Diabetologia 2001, 44, 1326–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Froguel, P.; Zouali, H.; Vionnet, N.; Velho, G.; Vaxillaire, M.; Sun, F.; Lesage, S.; Stoffel, M.; Takeda, J.; Passa, P. Familial Hyperglycemia Due to Mutations in Glucokinase. Definition of a Subtype of Diabetes Mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993, 328, 697–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, K.L.; Gloyn, A.L.; Colclough, K.; Batten, M.; Allen, L.I.S.; Beards, F.; Hattersley, A.T.; Ellard, S. Identification of 21 Novel Glucokinase (GCK) Mutations in UK and European Caucasians with Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young (MODY). Hum. Mutat. 2003, 22, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Han, X.; Zhou, X.; Li, Y.; Gong, S.; Zhang, S.; Cai, X.; Zhou, L.; Luo, Y.; Li, M.; et al. A New Clinical Screening Strategy and Prevalence Estimation for Glucokinase Variant-Induced Diabetes in an Adult Chinese Population. Genet. Med. 2019, 21, 939–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagen, J.V.; Odili, S.; Bjørkhaug, L.; Zelent, D.; Buettger, C.; Kwagh, J.; Stanley, C.; Dahl-Jørgensen, K.; de Beaufort, C.; Bell, G.I.; et al. From Clinicogenetic Studies of Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young to Unraveling Complex Mechanisms of Glucokinase Regulation. Diabetes 2006, 55, 1713–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delvecchio, M.; Mozzillo, E.; Salzano, G.; Iafusco, D.; Frontino, G.; Patera, P.I.; Rabbone, I.; Cherubini, V.; Grasso, V.; Tinto, N.; et al. Monogenic Diabetes Accounts for 6.3% of Cases Referred to 15 Italian Pediatric Diabetes Centers During 2007 to 2012. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 102, 1826–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvelos, M.I.; Gonçalves, C.I.; Coutinho, E.; Almeida, J.T.; Bastos, M.; Sampaio, M.L.; Melo, M.; Martins, S.; Dinis, I.; Mirante, A.; et al. Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young (MODY) in Portugal: Novel GCK, HNFA1 and HNFA4 Mutations. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, F.; Makino, H.; Hashimoto, N.; Taira, M.; Seino, S.; Bell, G.I.; Kanatsuka, A.; Yoshida, S. Type 2 (Non-Insulin-Dependent) Diabetes Mellitus Associated with a Mutation of the Glucokinase Gene in a Japanese Family. Diabetologia 1993, 36, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Massa, O.; Meschi, F.; Cuesta-Munoz, A.; Caumo, A.; Cerutti, F.; Toni, S.; Cherubini, V.; Guazzarotti, L.; Sulli, N.; Matschinsky, F.M.; et al. High Prevalence of Glucokinase Mutations in Italian Children with MODY. Influence on Glucose Tolerance, First-Phase Insulin Response, Insulin Sensitivity and BMI. Diabetologia 2001, 44, 898–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Steele, A.M.; Shields, B.M.; Wensley, K.J.; Colclough, K.; Ellard, S.; Hattersley, A.T. Prevalence of Vascular Complications among Patients with Glucokinase Mutations and Prolonged, Mild Hyperglycemia. JAMA 2014, 311, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, N.L.; Osbak, K.K.; van de Bunt, M.; Tribble, N.D.; Steele, A.M.; Wensley, K.J.; Edghill, E.L.; Colcough, K.; Barrett, A.; Valentínová, L.; et al. Insights into the Pathogenicity of Rare Missense GCK Variants from the Identification and Functional Characterization of Compound Heterozygous and Double Mutations Inherited in Cis. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 1482–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemssen, F.; Bellanné-Chantelot, C.; Osterhoff, M.; Schatz, H.; Pfeiffer, A.F.H. To: Lindner T, Cockburn BN, Bell GI (1999). Molecular Genetics of MODY in Germany. Diabetologia 42: 121–123. Diabetologia 2002, 45, 286–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruhova, S.; Dusatkova, P.; Sumnik, Z.; Kolouskova, S.; Pedersen, O.; Hansen, T.; Cinek, O.; Lebl, J. Glucokinase Diabetes in 103 Families from a Country-Based Study in the Czech Republic: Geographically Restricted Distribution of Two Prevalent GCK Mutations. Pediatr. Diabetes 2010, 11, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffel, M.; Froguel, P.; Takeda, J.; Zouali, H.; Vionnet, N.; Nishi, S.; Weber, I.T.; Harrison, R.W.; Pilkis, S.J.; Lesage, S. Human Glucokinase Gene: Isolation, Characterization, and Identification of Two Missense Mutations Linked to Early-Onset Non-Insulin-Dependent (Type 2) Diabetes Mellitus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 7698–7702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estalella, I.; Rica, I.; Perez de Nanclares, G.; Bilbao, J.R.; Vazquez, J.A.; San Pedro, J.I.; Busturia, M.A.; Castaño, L. Spanish MODY Group Mutations in GCK and HNF-1alpha Explain the Majority of Cases with Clinical Diagnosis of MODY in Spain. Clin. Endocrinol. 2007, 67, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloyn, A.L. Glucokinase (GCK) Mutations in Hyper- and Hypoglycemia: Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young, Permanent Neonatal Diabetes, and Hyperinsulinemia of Infancy. Hum. Mutat. 2003, 22, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caswell, R.C.; Snowsill, T.; Houghton, J.A.L.; Chakera, A.J.; Shepherd, M.H.; Laver, T.W.; Knight, B.A.; Wright, D.; Hattersley, A.T.; Ellard, S. Noninvasive Fetal Genotyping by Droplet Digital PCR to Identify Maternally Inherited Monogenic Diabetes Variants. Clin. Chem. 2020, 66, 958–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Diao, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, M.; Zhang, H.; Ping, F.; Li, M.; et al. Identification and Functional Analysis of GCK Gene Mutations in 12 Chinese Families with Hyperglycemia. J. Diabetes Investig. 2019, 10, 963–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoffel, M.; Bell, K.L.; Blackburn, C.L.; Powell, K.L.; Seo, T.S.; Takeda, J.; Vionnet, N.; Xiang, K.S.; Gidh-Jain, M.; Pilkis, S.J. Identification of Glucokinase Mutations in Subjects with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes 1993, 42, 937–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanyoura, M.; Letourneau, L.; Knight Johnson, A.E.; del Gaudio, D.; Greeley, S.A.W.; Philipson, L.H.; Naylor, R.N. GCK-MODY in the US Monogenic Diabetes Registry: Description of 27 Unpublished Variants. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 151, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruhova, S.; Ek, J.; Lebl, J.; Sumnik, Z.; Saudek, F.; Andel, M.; Pedersen, O.; Hansen, T. Genetic Epidemiology of MODY in the Czech Republic: New Mutations in the MODY Genes HNF-4alpha, GCK and HNF-1alpha. Diabetologia 2003, 46, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonfig, W.; Hermanns, S.; Warncke, K.; Eder, G.; Engelsberger, I.; Burdach, S.; Ziegler, A.G.; Lohse, P. GCK-MODY (MODY 2) Caused by a Novel p.Phe330Ser Mutation. ISRN Pediatr. 2011, 2011, 676549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuzawa, G.K.; Giuffrida, F.M.A.; Oliveira, C.S.V.; Chacra, A.R.; Dib, S.A.; Reis, A.F. Low Prevalence of MODY2 and MODY3 Mutations in Brazilian Individuals with Clinical MODY Phenotype. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2008, 81, e12–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, A.; Ek, J.; Mortensen, H.B.; Pedersen, O.; Hansen, T. Half of Clinically Defined Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young Patients in Denmark Do Not Have Mutations in HNF4A, GCK, and TCF1. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 4607–4614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, J.T.; Vasta, V.; Zhang, M.; Narayanan, J.; Gerrits, P.; Hahn, S.H. Molecular Genetic Testing of Patients with Monogenic Diabetes and Hyperinsulinism. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2015, 114, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shammas, C.; Neocleous, V.; Phelan, M.M.; Lian, L.-Y.; Skordis, N.; Phylactou, L.A. A Report of 2 New Cases of MODY2 and Review of the Literature: Implications in the Search for Type 2 Diabetes Drugs. Metabolism 2013, 62, 1535–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).