Structural Optimization Design of Rotary Drilling Rig Drill Pipes Based on an Improved Enhanced Knowledge Gain Sharing Algorithm

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Verification of Drill Pipe Load Capacity for Rotary Drilling Rigs

2.1. Operating Condition Classification

2.2. Working Principle of Drill Pipes

2.3. Drill Pipe Load Capacity Verification

2.3.1. Static Strength Verification

2.3.2. Stiffness Verification

2.3.3. Stability Verification

2.3.4. Fatigue Strength Verification

3. Lightweight Design of Drill Pipe Structure

3.1. Objective Function and Design Variables

3.2. Constraints

3.2.1. Static Strength Constraint

3.2.2. Stiffness Constraint

3.2.3. Stability Constraint

3.2.4. Fatigue Strength Constraint

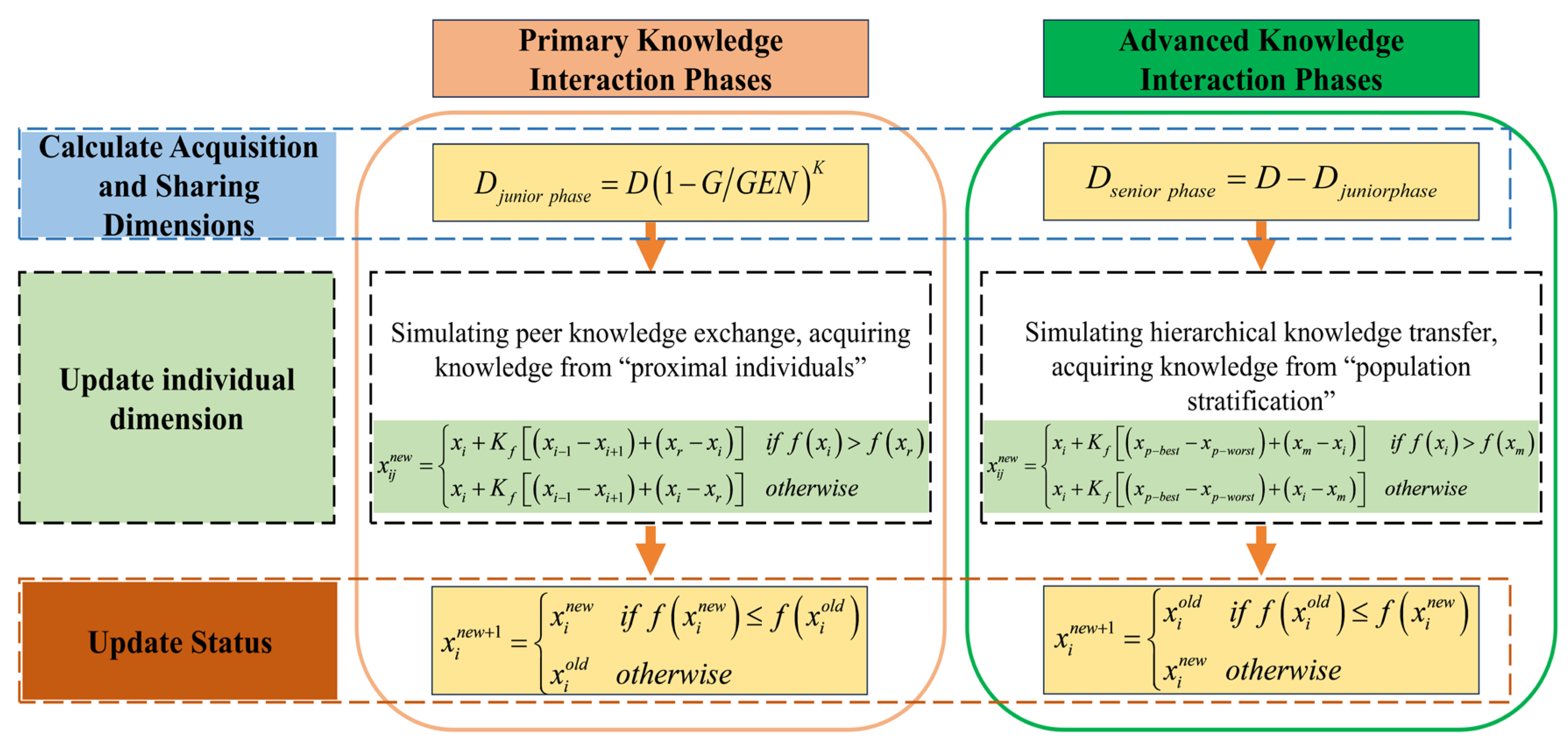

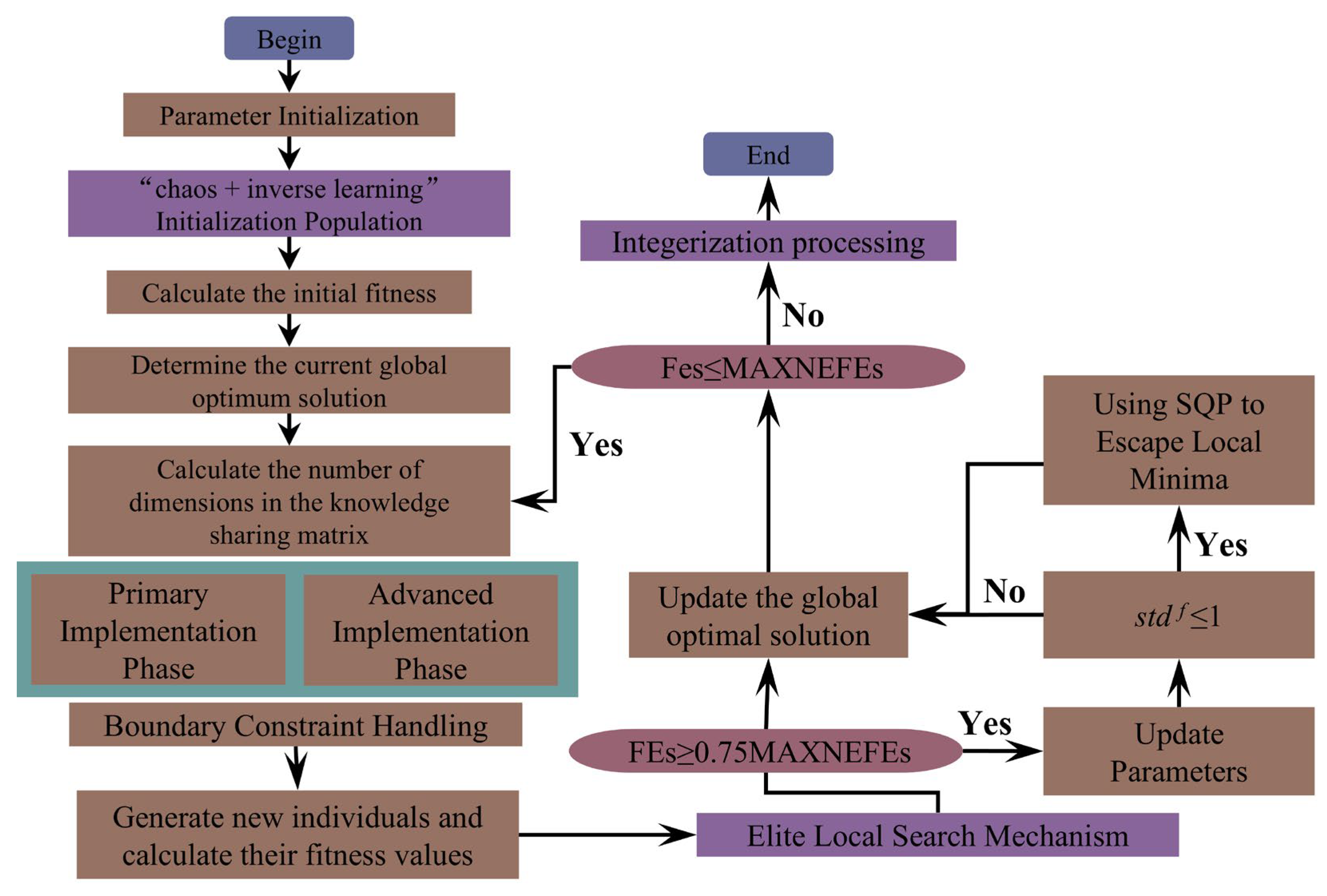

4. IeGSK Algorithm

4.1. Principles and Physical Significance of the eGSK Algorithm

4.2. IeGSK Algorithm

4.2.1. Hybrid Initialization Strategy

4.2.2. Integerization of Solutions

4.2.3. Elite Local Search Mechanism

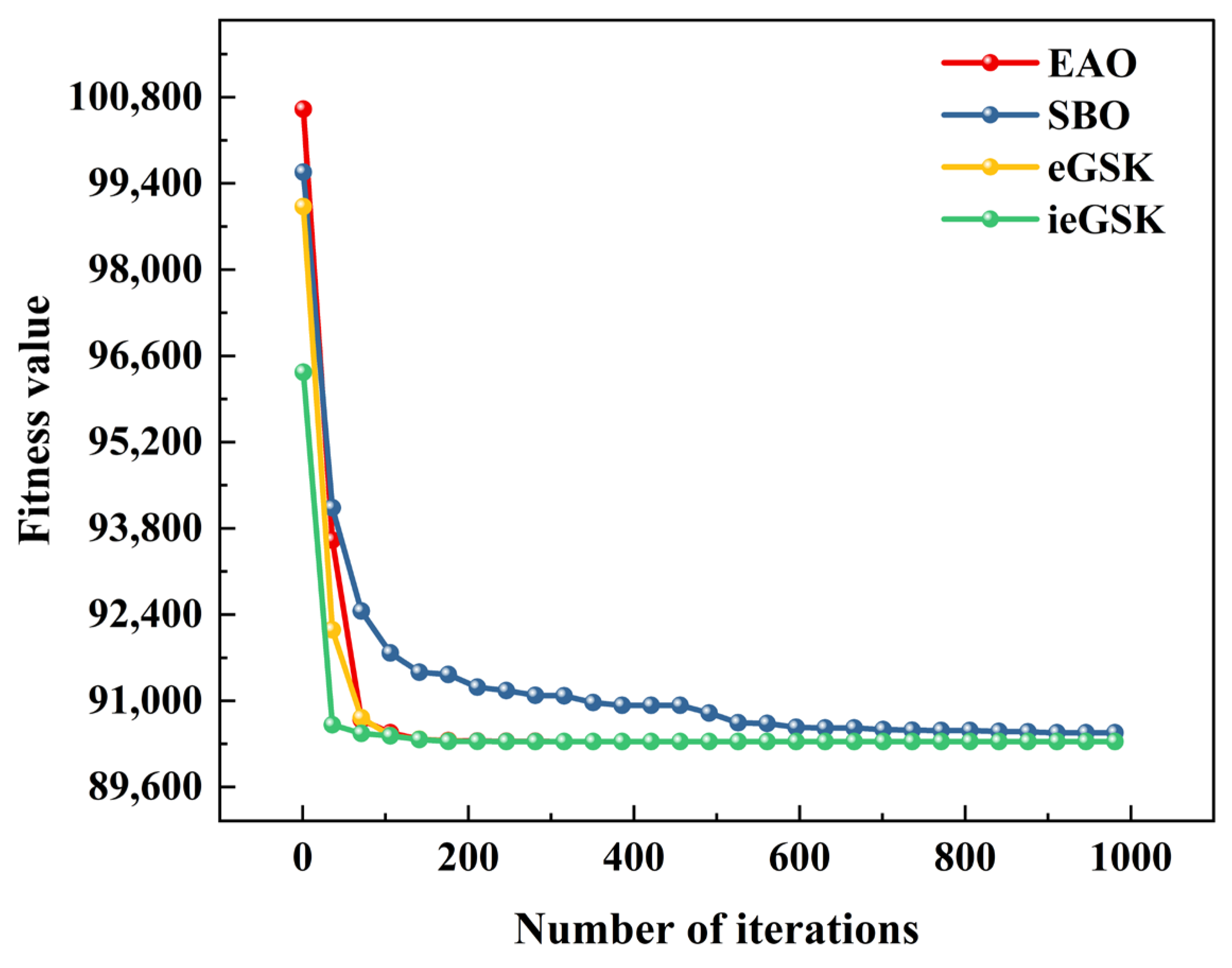

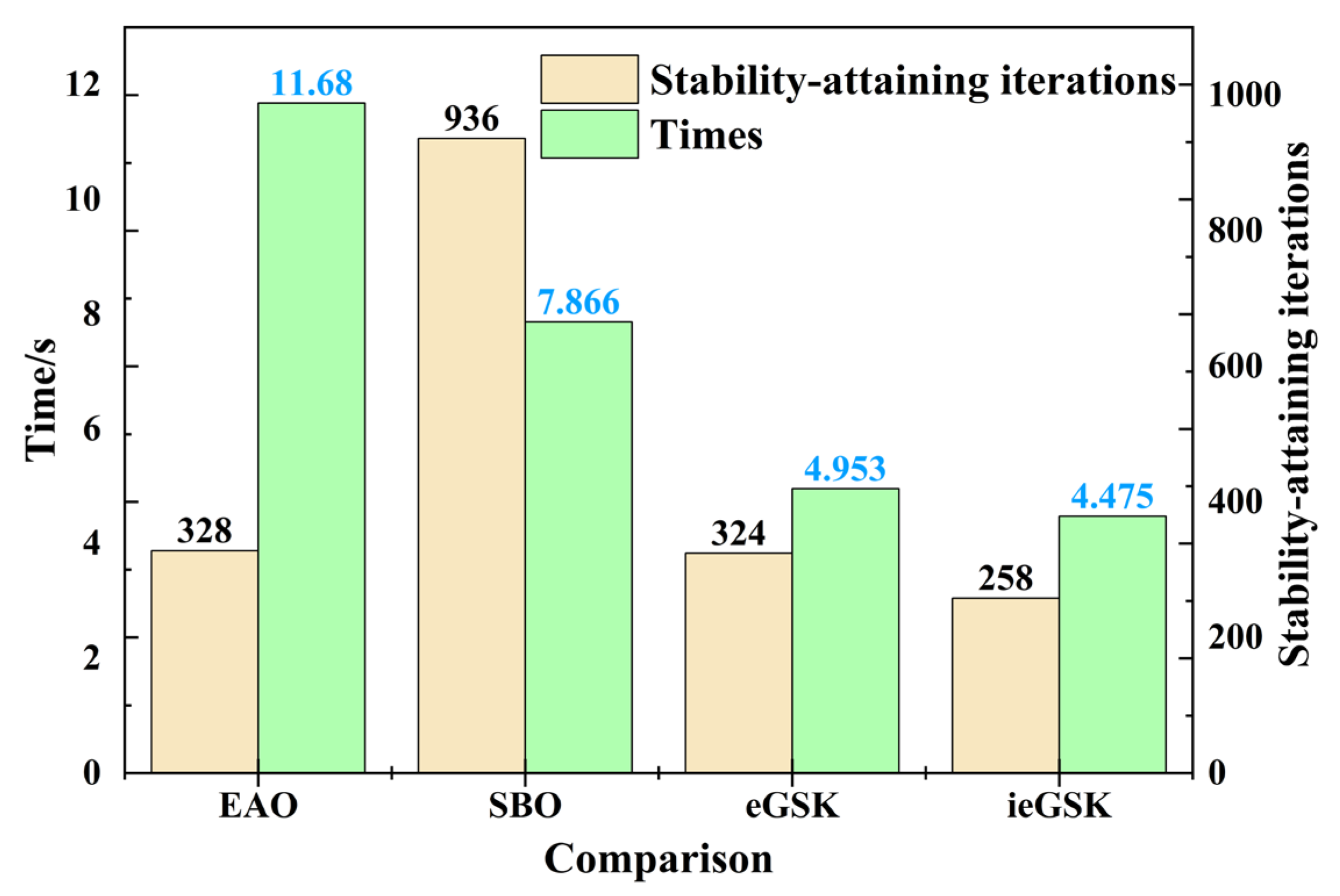

5. Engineering Case Studies

5.1. Parameter Settings

5.2. Constraints

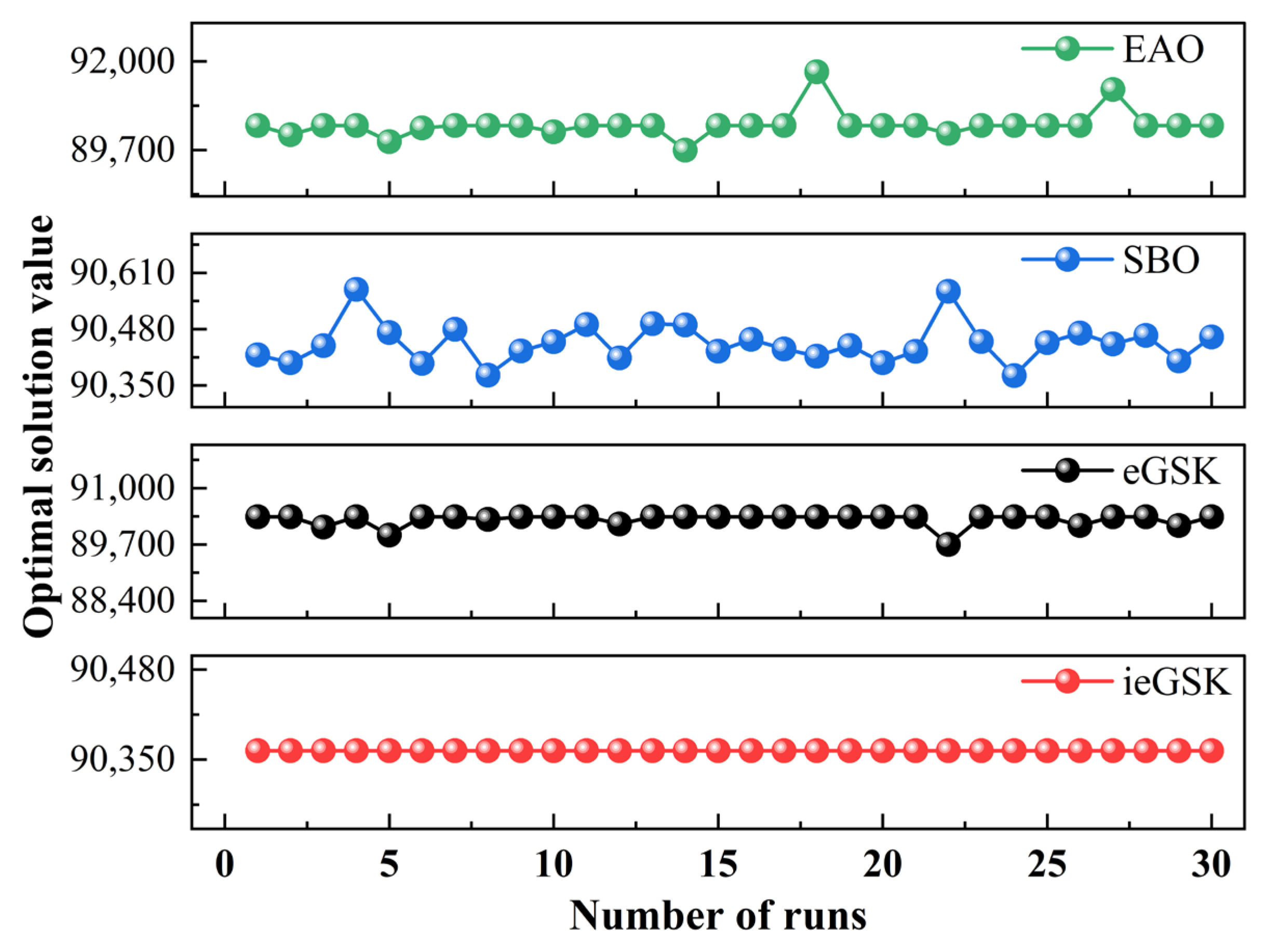

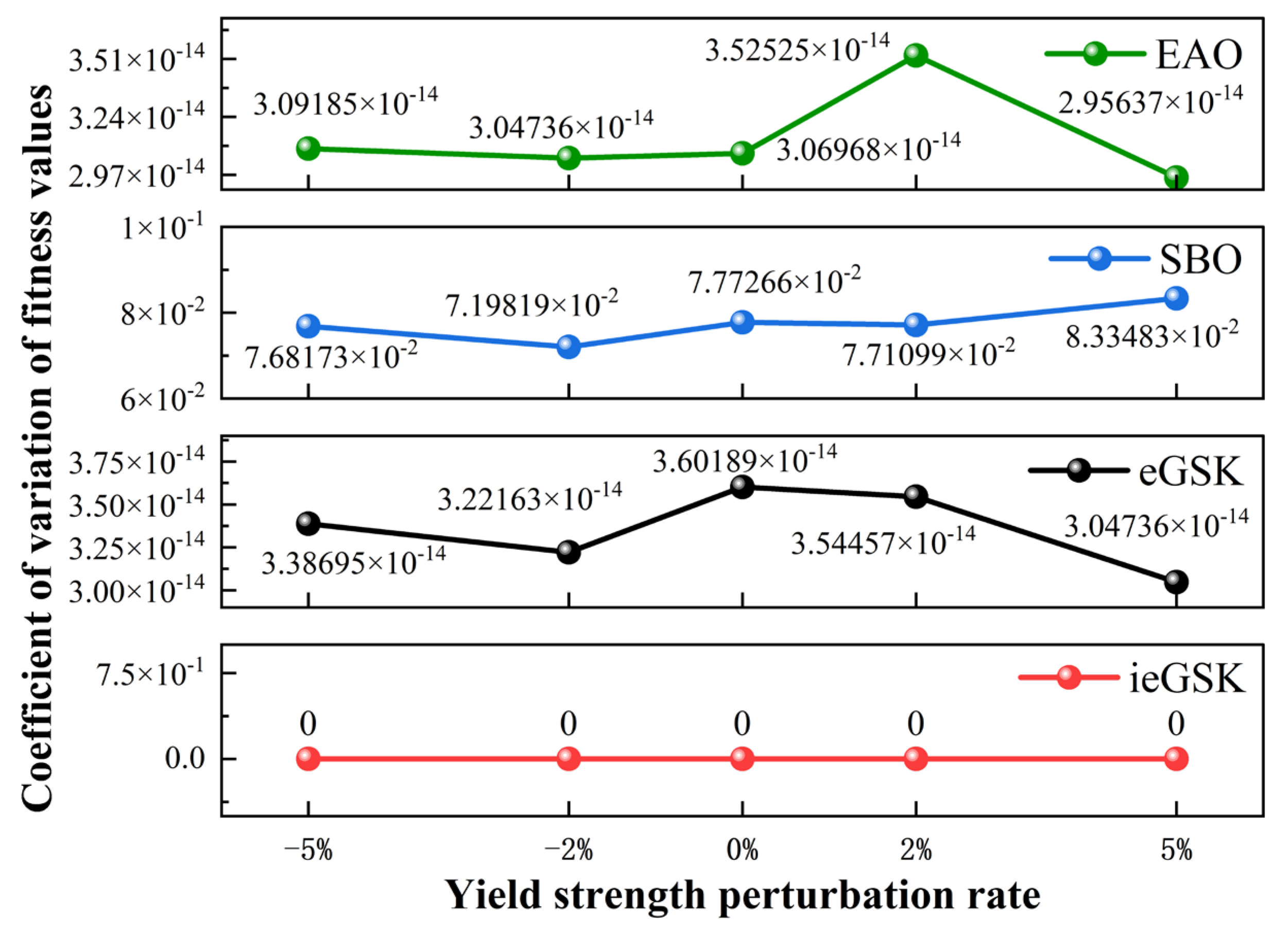

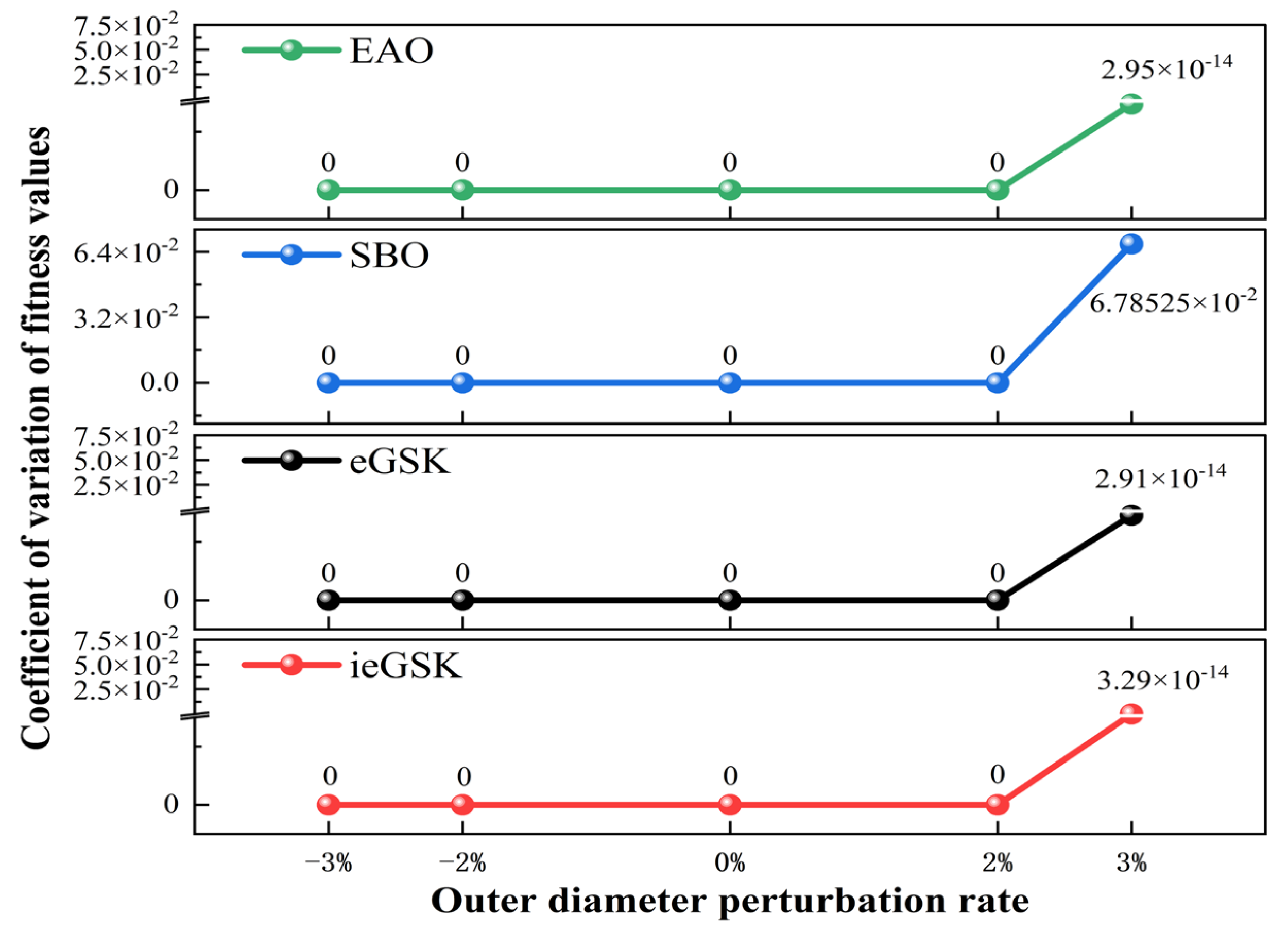

5.3. Optimization Results and Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| eGSK | Enhanced Gaining–Sharing Knowledge |

| ieGSK | Improved Enhanced Gaining–Sharing Knowledge |

| SBO | State-Based Optimization |

| EAO | Enzyme-Activated Optimization |

References

- Shabakhty, N.; Karimi, H.R.; Yeganeh-Bakhtiary, A.; Ghanbarian, M. Structural optimization of offshore jacket platforms considering structure-pile-soil interactions, using a continuous genetic algorithm. Appl. Ocean Res. 2025, 164, 104767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, F.; Jin, Y. Crashworthiness analysis and structural optimization of thin-walled circular tubes with porous arrays. Structures 2024, 70, 107811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borwankar, P.; Kapania, R.K.; Inoyama, D.; Stoumbos, T. Integrated structural design optimization of space vehicles with multidisciplinary constraints. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2026, 168, 110906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, A.R. A new hybrid particle swarm optimization approach for structural design optimization in the automotive industry. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 2012, 226, 1340–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Meng, Z. Design on low noise and lightweight of aircraft equipment cabin based on genetic algorithm and variable-complexity model. J. Vibroengineering 2015, 17, 2066–2076. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, M.-Y.; Prayogo, D. A novel fuzzy adaptive teaching–learning-based optimization (FATLBO) for solving structural optimization problems. Eng. Comput. 2016, 33, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Ci, S.; Liu, D.; Cheng, X.; Pan, Z. A Hybrid Multi-Objective Optimization Method Based on NSGA-II Algorithm and Entropy Weighted TOPSIS for Lightweight Design of Dump Truck Carriage. Machines 2021, 9, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Wang, Z. Enhancing population diversity based gaining-sharing knowledge based algorithm for global optimization and engineering design problems. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 252, 123958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, H. An improved guide weight method for multi-constraints structural optimization design. Structures 2025, 77, 109058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Yan, Y.; Yan, X.; Zhao, L. Structural Parameters Optimization of Elastic Cell in a Near-Bit Drilling Engineering Parameters Measurement Sub. Sensors 2019, 19, 3343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ooi, K.T.; He, L.; Zhao, S.; Luo, Q.; Liu, W.; Liu, Z. Structural optimization design of dimple plate heat exchanger based on machine learning. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2025, 167, 109271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, S.; Tian, Y.; Wang, B.; Chen, Y. Structural optimization design of rotary table of CNC grinding machine based on NSGA-II algorithm. Mach. Tool Hydraul. 2025, 53, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Stolpe, M.; Sandal, K. Structural optimization with several discrete design variables per part by outer approximation. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2018, 57, 2061–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.; Barman, A.G. An approach for design optimization of helical gear pair with balanced specific sliding and modified tooth profile. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2019, 60, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Xia, X.; Yang, F.; Shi, D.; Song, M. Welding distortion investigation of rotary drill rig pipe with radial loading transition bars. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2022, 199, 104704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Tan, Z. Fatigue life analysis of rotary drill pipe. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2023, 201, 104874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Li, L.-g.; Yi, W.; Li, X. Working Performance Analysis and Optimization Design of Rotary Drilling Rig under on Hard Formation Conditions. Procedia Eng. 2014, 73, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Ni, H.; Wang, R. A novel vibration drilling tool used for reducing friction and improve the penetration rate of petroleum drilling. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2018, 165, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniyi, A.; Igbafe, A.; Ebis, O.; Ogunyemi, A.; Yusuff, S.; Oyebode, O. Design and Construction of Rotary Drilling Rig Prototype. Soc. Pet. Eng. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q. Research and Design of Rotary Drilling Rigs; Central South University Press: Changsha, China, 2012; p. 412. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Ren, Y.; Xu, G. Optimization of Rotary Drilling Rig Mast Structure Based on Multi-Dimensional Improved Salp Swarm Algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D. The Analysis and Optimalize of the Machine-locked Drilling Rod of Rotary Drill. Master’s Thesis, North University Of China, Taiyuan, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Jiao, S.; Wu, F. Rotary Drilling Rig and the Construction Technology; People’s Communications Press: Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Kong, J.; Yang, J. Modern Mechanical Designer’s Handbook; China Machine Press: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, G. Design of Metal Structure for Mechanical Equipment; China Machine Press: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 8686-1; Cranes-Design principles for loads and load combinations—Part 1: General first ed. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- Sun, J.; Liang, Y. Optimal Design of Machine; China Machine Press: Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jawad, M.A.; Roshdy, H.S.M.; Mohamed, A.W. Enhanced Gaining-Sharing Knowledge-based algorithm. Results Control Optim. 2025, 19, 100542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, J.-S.; Ngo, N.-T. Modified firefly algorithm for multidimensional optimization in structural design problems. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2016, 55, 2013–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, S.; Mohapatra, P. Fast random opposition-based learning Golden Jackal Optimization algorithm. Knowl. -Based Syst. 2023, 275, 110679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Lu, C.; Heidari, A.A.; Wu, Z.; Chen, H. The status-based optimization: Algorithm and comprehensive performance analysis. Neurocomputing 2025, 647, 130603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodan, A.; Al-Tamimi, A.-K.; Al-Alnemer, L.; Mirjalili, S.; Tiňo, P. Enzyme action optimizer: A novel bio-inspired optimization algorithm. J. Supercomput. 2025, 81, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Operating Conditions | Instruction |

|---|---|

| Drilling Operation B1 | The drill pipe transmits torque and pressure to the drill bit to complete drilling. |

| Out-of-Hole Lifting Operation B2 | The winch lifts the drill pipe, raising it vertically. |

| In-Hole Lifting Operation B3 | The winch lifts the drill pipe, with the pressure cylinder assisted by the power head. |

| Dirt-Slinging Operation B4 | The power head rotates forward and backward to dislodge soil through impact. |

| Dirt-Shaking Operation B5 | The winch continuously starts and stops, moving the drill pipe up and down to dislodge soil by inertia. |

| Traveling Operation B6 | The entire machine moves. |

| Rotation Operation B7 | The chassis remains stationary while the upper structure rotates. |

| xi1 | xi2 | xi3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| i = 1 | [13, 14] | [40, 60] | [20, 25] |

| i = 2 | [13, 14] | [40, 60] | [20, 25] |

| i = 3 | [13, 14] | [40, 60] | [20, 25] |

| i = 4 | [20, 25] | [40, 60] | [20, 25] |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Powerhead Weight GPH | 10.92 kN |

| Drill Pipe 1 Weight GP1 | 43.65 kN |

| Drill Pipe 2 Weight GP2 | 32.12 kN |

| Drill Pipe 3 Weight GP3 | 30.21 kN |

| Drill Pipe 4 Weight GP4 | 32.27 kN |

| Pressure Applied FPCP | 532.48 kN |

| Torque MPH | 499.2 kN·m |

| Distance from Drill Pipe 1 to Top Z1 | 15,950 mm |

| Distance from Drill Pipe 2 to Top Z2 | 30,315 mm |

| Distance from Drill Pipe 3 to Top Z3 | 44,545 mm |

| Distance from Drill Pipe 4 to Top Z4 | 60,670 mm |

| The yield strength of drill pipe 1 σs1 | 550 MPa |

| The yield strength of drill pipe 2 σs2 | 550 MPa |

| The yield strength of drill pipe 3 σs3 | 850 MPa |

| The yield strength of drill pipe 4 σs4 | 850 MPa |

| Key compression Strength σkc | 900 MPa |

| Key shear Strength σks | 1200 MPa |

| gi(x) | Formula | Meet the Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Before Optimization | After Optimization | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAO | SBO | eGSK | ieGSK | ||

| x11 (mm) | 14 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 |

| x12 (mm) | 60 | 51.84 | 57.52 | 51.84 | 52 |

| x13 (mm) | 25 | 25 | 23.54 | 25 | 25 |

| x21 (mm) | 14 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 |

| x22 (mm) | 40 | 40 | 40.02 | 40 | 40 |

| x23 (mm) | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| x31 (mm) | 14 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 |

| x32 (mm) | 60 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 |

| x33 (mm) | 30 | 20 | 20.01 | 20 | 20 |

| x41 (mm) | 25 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| x42 (mm) | 40 | 50 | 48.46 | 50 | 50 |

| x43 (mm) | 20 | 30 | 29.98 | 30 | 30 |

| Fitness value (mm2) | 100,205.21 | 90,338.76 | 90,479.18 | 90,338.76 | 90,362.83 |

| Weight Loss Percentage (%) | - | 9.8 | 9.7 | 9.8 | 9.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, H.; Yang, H.; Xu, G.; Yang, M. Structural Optimization Design of Rotary Drilling Rig Drill Pipes Based on an Improved Enhanced Knowledge Gain Sharing Algorithm. Machines 2026, 14, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14010048

Yang H, Yang H, Xu G, Yang M. Structural Optimization Design of Rotary Drilling Rig Drill Pipes Based on an Improved Enhanced Knowledge Gain Sharing Algorithm. Machines. 2026; 14(1):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14010048

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Heng, Haorong Yang, Gening Xu, and Mingliang Yang. 2026. "Structural Optimization Design of Rotary Drilling Rig Drill Pipes Based on an Improved Enhanced Knowledge Gain Sharing Algorithm" Machines 14, no. 1: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14010048

APA StyleYang, H., Yang, H., Xu, G., & Yang, M. (2026). Structural Optimization Design of Rotary Drilling Rig Drill Pipes Based on an Improved Enhanced Knowledge Gain Sharing Algorithm. Machines, 14(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14010048