1. Introduction

Behavior planning is one of the most critical subsystems in an autonomous driving system [

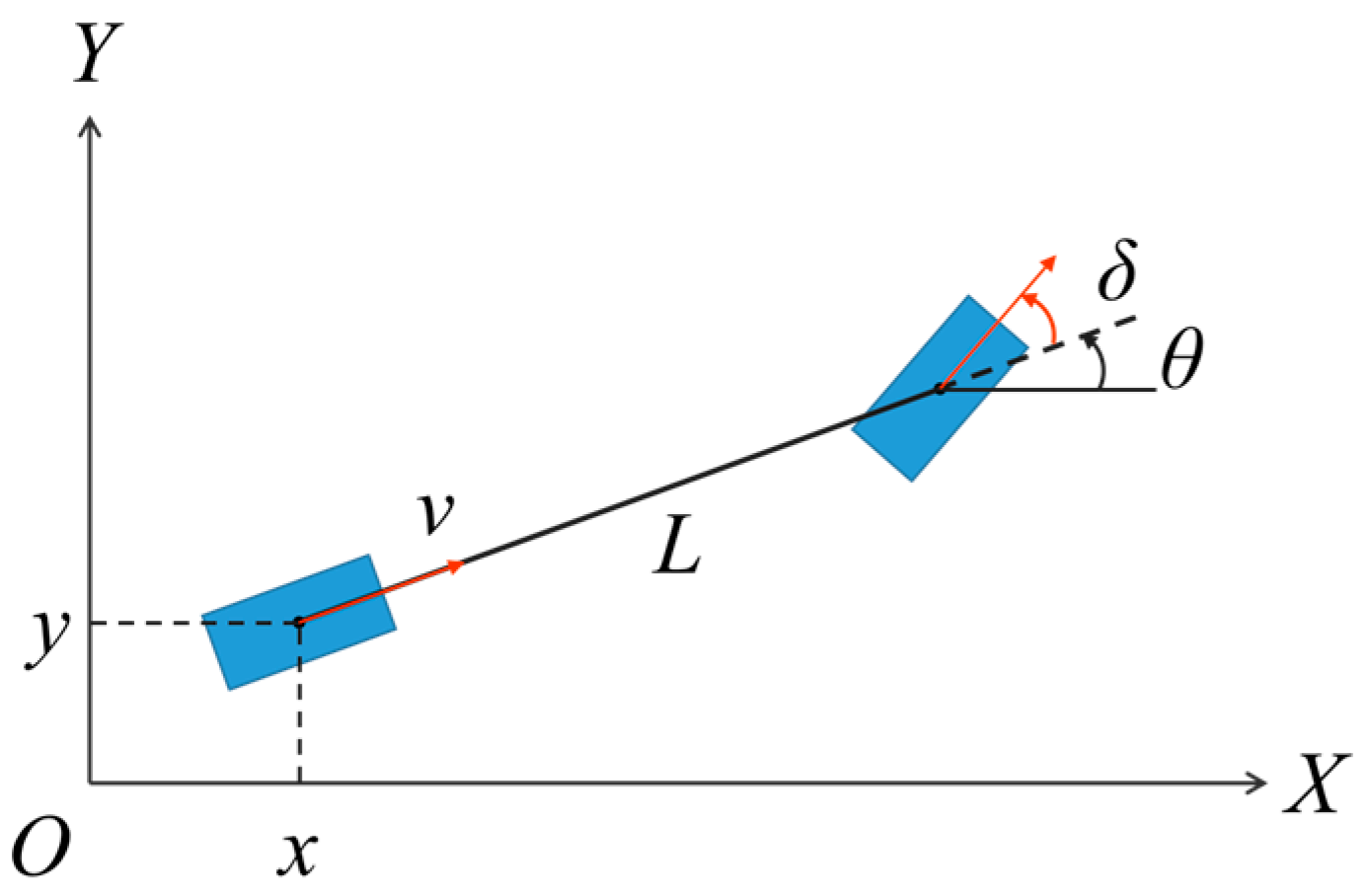

1,

2]. Benefiting from the advancement of driving models, high-quality and human-like trajectories can now be predicted more naturally. However, driving models do not always predict the correct behavior at the appropriate moment. For safety and other considerations, a robust behavior planning framework is typically expected to help driving models enhance their actual performance [

3]. Specifically, driving models should work in conjunction with a proper behavior planner to achieve safe, comfortable, and efficient autonomous driving experiences.

Common behavior planning methods can be categorized into two main types: rule-based planners and model-based end-to-end planners. First, rule-based planners—such as the lattice trajectory planner [

4] and Baidu Apollo EM planner [

5] are built on heuristic or optimization algorithms. These planners offer strong explainability, ease of maintenance, and computational efficiency, making them widely adopted in several leading autonomous driving systems worldwide. Specifically, explainability refers to the property that during the decision-making process of a decider, the reasoning logic, as well as the causes and consequences, can be clearly explained or intuitively demonstrated. For instance, when the ego-vehicle makes a left turn at an intersection, we can trace the reason to the fact that the ego-vehicle is in a left-turn-only lane; thus, the subsequent path must be a left turn. However, their performance may degrade in complex driving scenarios [

6]. In contrast, learned planning model-based end-to-end planners do not rely on explicit hand-crafted rules or algorithms [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Trained on massive autonomous driving datasets, they excel at solving problems that either require highly complex algorithms or are otherwise computationally intractable. Nevertheless, their training demands enormous volumes of data, and deployed models typically depend on high-performance computing platforms—factors that render their practical and stable application highly challenging [

11,

12,

13].

Building on the unique advantages of the two planner types discussed above, this paper aims to develop a novel algorithm that integrates their respective strengths. The core challenge in our proposed approach lies in the insufficient reliability and stability of trajectories predicted by learned planning model-based planners. The underlying reason is that while such planners elevate the upper limit of system performance, they may simultaneously lower the system’s lower bound of operational stability. During the experiments, we found that learned planning models may even exhibit inconsistent behaviors in simple scenarios. For example, when the preceding vehicle decelerates significantly and both sides of the ego-vehicle’s lane are marked with solid lines, the trajectories generated by the model sometimes involve a sharp deceleration, while at other times, the model may cross the solid lines and detour while decelerating. The latter behavior needs to be suppressed, as solid lines are generally non-crossable, and reckless crossing would pose extremely high safety risks. In contrast, rule-based planners typically make decisions (e.g., lane bias adjustments or lane changes) via predefined algorithms. However, when confronted with complex decision-making scenarios, the cascading effects of these decisions are often not adequately assessed—which may result in hazardous or operationally meaningless outcomes [

14]. To address these limitations, this paper proposes a learned planning model-based spatio-temporal decider. By evaluating the overall driving performance of trajectories generated by the driving model, the proposed decider ensures the final selected trajectory meets the requirements of safety, comfort, and efficiency. Notably, this spatio-temporal decider has been successfully and rigorously validated through both simulation tests and million-mile real-world experiments across urban and highway scenarios.

The main contributions of this paper are centered on two core modules of the decider: First, this paper proposes an innovative planning framework that integrates a learned planning model with spatio-temporal joint decision-making evaluation. It simultaneously addresses the drawbacks of insufficient reliability and stability in existing data-driven models, as well as the limitations of rule-based algorithms—namely, their low performance ceiling and often poor performance on corner cases.

Second, this paper incorporates innovations both in model design and evaluation algorithm design. For the model, a direct trajectory output approach is adopted, yielding more integrated and natural motion behaviors that better align with the overall concept of spatio-temporal joint planning. For the evaluation, on the basis of emphasizing driving safety in the planning model, the evaluation framework innovatively designs three metrics in the spatio-temporal dimension; through rational weight adjustment, it ensures the unity, efficiency, and stability of the overall framework at the spatio-temporal joint level.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 presents the necessary preliminaries for the subsequent analysis.

Section 3 details the main framework of the proposed learned planning model-based spatio-temporal decider, with key design principles and component interactions elaborated.

Section 4 presents and analyzes the results of both simulations and real-world experiments, including quantitative metrics and qualitative performance insights.

Section 5 provides concluding remarks on the study’s contributions and outlines key directions for future work.

3. Model-Based Spatio-Temporal Decider

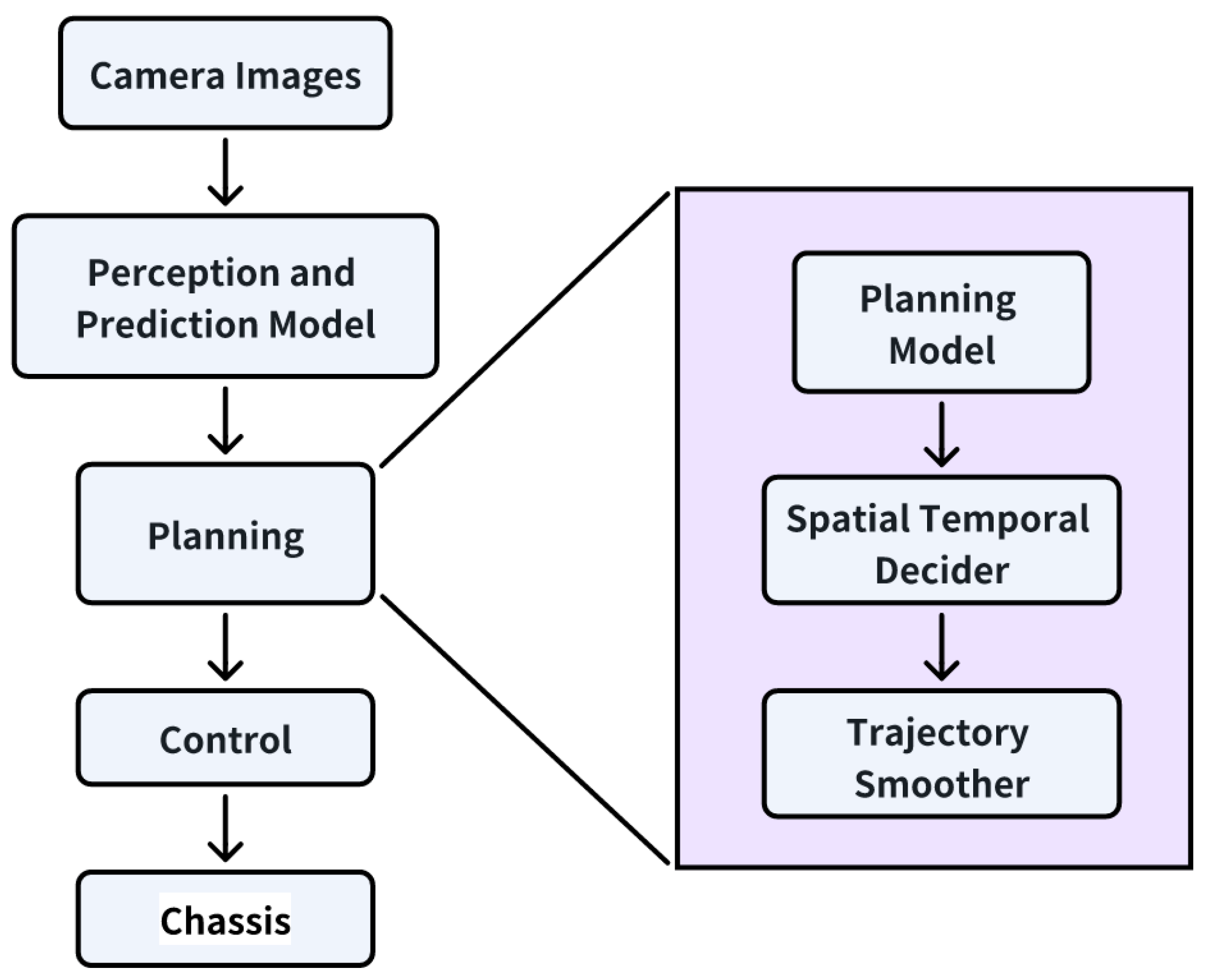

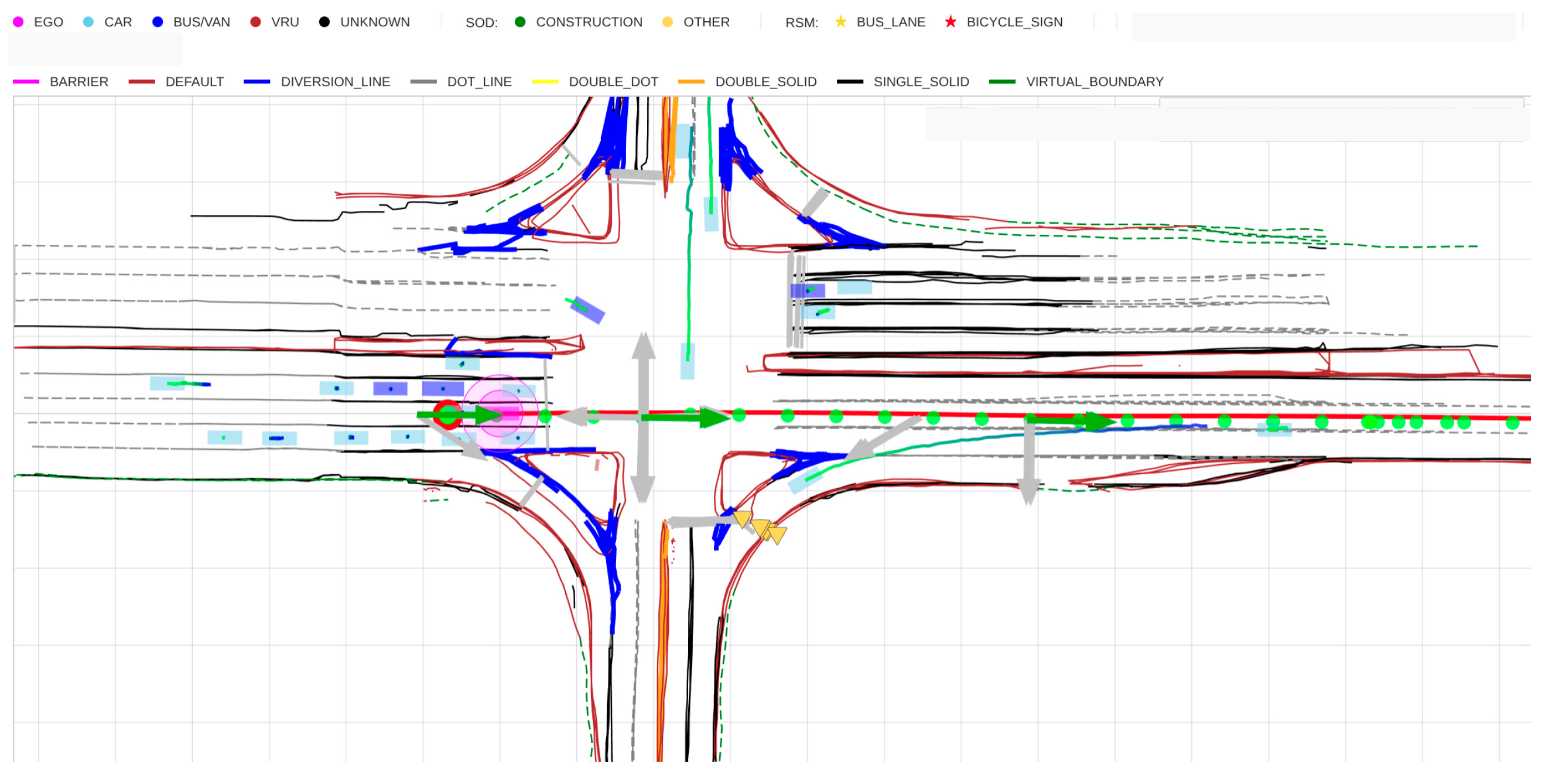

The two core modules of the learned planning model-based spatio-temporal behavior decider are elaborated in the subsequent two subsections. Prior to delving into these details, the overall framework of the Model-based Spatio-temporal Decider is first presented. As illustrated in

Figure 2, the proposed model-based spatio-temporal decider is embedded within a two-stage end-to-end autonomous driving model architecture. Specifically, the first-stage perception and prediction model takes camera images as input and outputs object detection results and motion predictions. In the planning module, the planning model accepts all static and dynamic perceptual outputs as inputs and then generates multiple candidate trajectories. Based on these candidate trajectories, the spatio-temporal decider makes an optimal selection; the chosen trajectory is subsequently smoothed to meet the control system requirements.

3.1. Trajectory Planning Model

Our trajectory planning model consists of two main networks, a scene encoder process environmental and dynamic information, while a decoder deals with cross-attention to scene encodings and ego motion tokens. The general planner is designed on a transformer architecture. The number of model parameters is determined primarily by the model architecture and the latency requirements for real-vehicle deployment. Following comprehensive analysis, we ultimately set the number of model parameters at around 0.1 billion. The scene encoder and trajectory decoder will be introduced in the following two subsections.

3.1.1. Scene Encoder

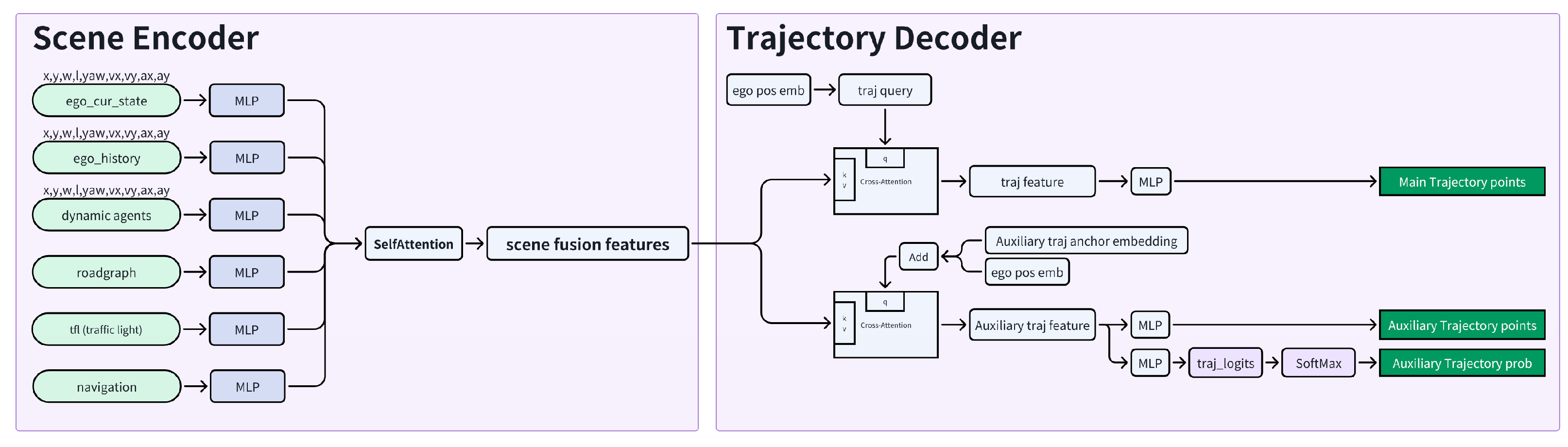

As illustrated in

Figure 3, the scene encoder processes diverse inputs and multi-modal data, encompassing the ego-vehicle’s current state, historical states, dynamic traffic agents’ states, road graph, traffic lights, and navigation information. The states of the ego-vehicle and traffic agents are characterized by their positions, velocities, accelerations, and dimensions. Specifically, the ego-vehicle’s current state and dynamic traffic agents’ states are detected from the current frame, while its historical states are aggregated across preceding frames. The integration of the ego-vehicle’s historical information is intended to enhance the planner’s temporal modeling capacity, thereby enabling the generation of continuous and stable trajectories. The road graph includes road boundaries, lane boundaries, stop lines, and other traffic markings. Navigation information comprises general routing details and recommendations provided by the navigation service. All input information is converted into identical 256-dimensional features via the Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) to align their dimensions and facilitate subsequent fusion. After encoding all input data, they are fused into an integrated feature vector. These fused features are subsequently fed into a self-attention block to model intrinsic relationships across the scene. Finally, the scene encoder yields a scene-level fused feature of relatively high dimension.

3.1.2. Trajectory Decoder

As illustrated in

Figure 3, the trajectory decoder comprises two main components: one generates a main trajectory, and the other generates auxiliary trajectories. Details of these two decoder heads are elaborated below.

The main trajectory is decoded via a Transformer decoder architecture, where the query is primarily derived from the ego-vehicle’s position embedding, and the keys and values are the fused scene features output by the scene encoder. The fused scene features provide all the essential information required for us to parse the trajectory, as they integrate static and dynamic elements into high-dimensional information for utilization by the decoder. The ego-vehicle’s position embedding and scene features are processed through cross-attention to model internal relationships. The trajectory features, output by the main trajectory cross-attention module, are then converted into final main trajectory points via a multi-layer perceptron (MLP). The Transformer decoder is configured with a dimension of 256 and 8 layers. The main trajectory consists of 24 points, forming a 6 s trajectory with a time resolution of 0.25 s. Corresponding to the main trajectory decoder, two loss functions are designed: an imitation loss and a collision loss. The imitation loss aims to guide the model to mimic human driving trajectories using ground truth data. To further ensure safety, the collision loss is calculated based on the distance between the ego-vehicle’s trajectory bounding box and the bounding boxes of agents’ trajectories in the ground truth. These two losses are summed to form the total loss, with the imitation loss assigned a dominant weight.

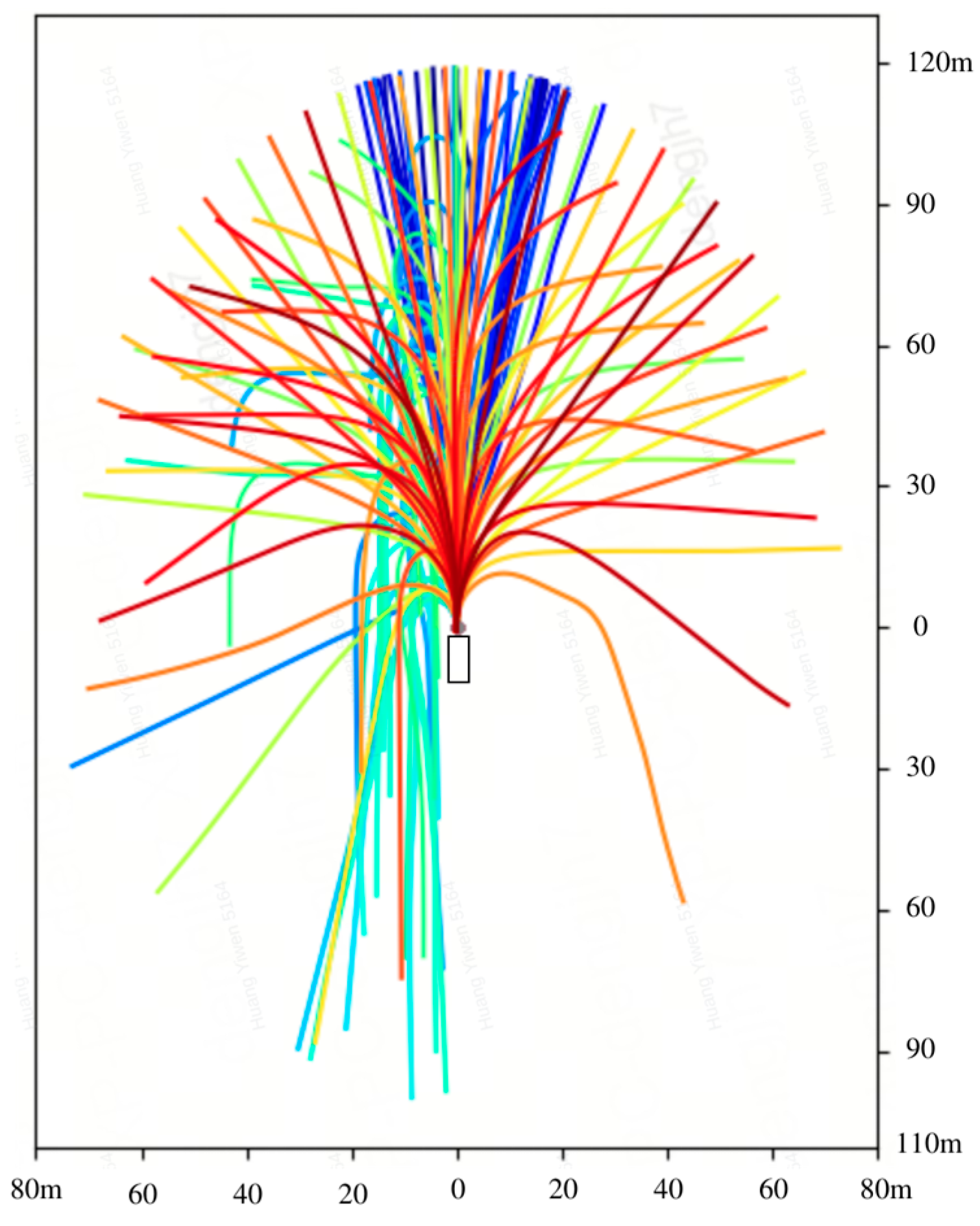

To enhance trajectory diversity, an auxiliary trajectory decoder head is also designed. For this purpose, the ego-vehicle’s position embedding is merged with predefined trajectory anchors to form the query for the Transformer. These trajectory anchors are determined based on statistical analysis of the diversity in ground truth trajectories. We statistically analyzed the driving trajectory of each piece of data from as many as 15 million driving data samples, resulting in a detailed distribution list and corresponding trajectory shapes, as shown in

Figure 4. Specifically, 48 anchors are defined to meet diversity requirements, covering lane changes, turns, U-turns, and other typical maneuvers. Similar to the main trajectory decoder, the keys and values here also use the fused scene features from the scene encoder, and the Transformer decoder shares the same configuration (256 dimensions, 8 layers). For each anchor in the fused query, a corresponding trajectory is encoded in the auxiliary trajectory feature. This feature is first mapped to auxiliary trajectories through an MLP structure. Unlike the main trajectory, this head outputs 48 trajectories, each consisting of 24 points to form a 6 s trajectory (with a 0.25 s resolution). Additionally, the probability of each auxiliary trajectory is critical within the overall spatio-temporal framework, as it provides a ranking mechanism. The probability of each auxiliary trajectory is determined by its similarity to the ground truth trajectory.

3.1.3. Training Dataset

The training dataset for the planning model comprises 5 million video clips, each 20 s in duration. Each clip is split into 20 pickle files, with each file containing 10 s of historical data and 20 s of future data. Altogether, this results in a total of 100 million pickle files across the entire dataset. All data are collected via a customer-owned vehicle fleet, which contributes over 1 million new clips monthly—supporting ongoing model iteration and expansion. As illustrated in

Figure 5, a sample pickle file encapsulates all essential information, including road graphs, as well as ground truth trajectories of the ego-vehicle and surrounding agents. The dataset covers a diverse range of scenarios, with distributions as follows: urban roads (80%), city expressways (10%), and highways (10%). Within the urban road category specifically, typical driving scenarios and maneuvers are comprehensively included, such as intersections, U-turns, straight driving, lane changes, and other common operations. The data scenario ratio was selected in this way because our model is primarily designed to address the long-tail problems in urban scenarios, which are also pain points in the industry. In contrast, highway and expressway scenarios are relatively less complex, and a 10% data ratio is sufficient to ensure the model achieves satisfactory performance in these scenarios.

3.1.4. Training Setups and Metrics

Our model was trained on an NVIDIA A100 cluster using 128 GPUs, with a total of 50,000 training steps. The optimizer used is AdamW, the learning rate scheduling strategy adopts cosine annealing, and the batch size is set to 128. After training, we conduct open-loop metric evaluation of the model using the test dataset, which typically includes ADE (Average Displacement Error), FDE (Final Displacement Error), trajectory centricity, trajectory smoothness, and others. Partial evaluation metrics are presented in

Table 1. It can be seen that the metrics demonstrate that our model performs excellently in all the aforementioned indicators.

3.2. Spatio-Temporal Evaluation

As outlined in

Section 3.1, the planning model generates one main trajectory and 48 auxiliary trajectories. Herein, we evaluate all generated trajectories and select the optimal one as the final executable trajectory. The core of the trajectory evaluation module lies in the formulation of evaluation criteria. Given that the quality of the model’s output trajectories has already been validated by the training metrics—with guaranteed high performance and safety—we adopt a simplified heuristic evaluation framework, focusing on three key dimensions: travel efficiency, riding comfort, and lateral stability. Detailed evaluation methodologies are elaborated below.

3.2.1. Efficiency Cost

Travel efficiency of a trajectory is evaluated based on two core metrics: terminal speed and total trajectory length. As the planning horizon of the model is set to 6 s, the vehicle’s terminal speed (at the 6 s mark) directly reflects efficiency—with higher terminal speed indicating superior efficiency. Beyond terminal speed, the total trajectory length (i.e., the distance traveled by the vehicle within the 6s planning window) is also considered, where a longer trajectory corresponds to higher efficiency. To standardize the evaluation scale, the costs associated with terminal speed and trajectory length are normalized relative to a “do-nothing trajectory” (a baseline trajectory with no active maneuvering), which is achieved by calculating a speed loss and a length loss, respectively. To further clarify the definition of “do-nothing trajectory”: this trajectory is generated based on the ego-vehicle’s current state information (including speed, acceleration, heading angle, and steering wheel angle), and it represents a trajectory where the vehicle naturally returns to straight-line uniform motion without any input of human actions. The generation of this trajectory is achieved through modeling with the Vehicle Kinematic Model mentioned in

Section 2.1. The speed loss is calculated as

The length loss is calculated as

Each loss contributes 50% to the total efficiency cost, which is a number between 0 to 1. The efficiency cost is calculated as

3.2.2. Riding Comfort Cost

Riding comfort of a trajectory is evaluated based on two key metrics: the maximum absolute longitudinal acceleration

and the maximum absolute centripetal acceleration

(lateral acceleration equivalent). The riding comfort cost increases with the magnitude of either metric—higher maximum values correspond to poorer comfort and thus higher costs. Specifically, the maximum absolute longitudinal acceleration is defined as the absolute value of the maximum or minimum longitudinal acceleration across the entire trajectory. The maximum absolute centripetal acceleration refers to the absolute value of the maximum or minimum centripetal acceleration along the trajectory, which directly reflects lateral comfort performance. For each trajectory point, the centripetal acceleration is calculated as

, where

v denotes the speed at the target trajectory point and

represents the curvature of the corresponding path point. The acceleration threshold is set to 1.0 m/s

2 based on empirical judgments. By analyzing the driving data of human operators, we found that longitudinal and lateral maneuvers with an acceleration magnitude within 1.0 m/s

2 are generally considered to ensure a high level of ride comfort. Accordingly, the longitudinal and lateral riding comfort costs are computed as follows:

The longitudinal and lateral riding comfort costs each account for 50% of the total riding comfort cost, which is also normalized to a value ranging from 0 to 1. The total riding comfort cost is calculated as follows:

3.2.3. Lateral Stability Cost

The lateral stability of a trajectory is characterized by two metrics: its similarity to the previously planned trajectory and its proximity to the lane centerline. Specifically, for the first metric, the lateral deviation (denoted as

) between the terminal point of the evaluated trajectory and that of the previously planned trajectory is calculated within the same coordinate system. The lateral difference threshold is set to 3.0 m because the width of standard traffic lanes typically ranges from 3 to 4 m. We intended to evaluate the lateral stability of the vehicle based on the width of a single traffic lane. The cost associated with this lateral deviation is computed as follows:

Second, the lateral offset (denoted as

) between the terminal point of the evaluated trajectory and the lane centerline is computed. The cost associated with this lateral offset is calculated as follows:

The lateral deviation cost and lateral offset cost each account for 50% of the total lateral stability cost, which is also normalized to a value ranging from 0 to 1. The total lateral stability cost is calculated as follows:

3.2.4. Total Cost

The total cost is the weighted sum of efficiency, riding comfort, and lateral stability cost.

In Equation (12), the values of w1, w2, and w3 are set according to the requirements of different driving styles. We usually initially define the driving style as prioritizing comfort and stability, followed by efficiency. Therefore, we increase the weights of comfort (w2 = 1.5) and lateral stability (w3 = 1.2), while reducing the weight of efficiency (w1 = 0.8). To provide autonomous driving software with different driving styles, we increase the efficiency weight w1 to 1.5 for the version targeting driving efficiency and flexibility; for the version focusing on riding comfort, we raise the comfort weight w2 to 1.5. Other weights remain unchanged.

Since each cost has been individually normalized (to the range [0, 1]), we can directly identify the optimal trajectory and assess whether it offers sufficient performance gains relative to the do-nothing trajectory. If the optimal trajectory demonstrates a distinct advantage over the do-nothing trajectory, we execute the corresponding maneuver decision and pass the optimal trajectory to a refined trajectory planning process. Two criteria are used to validate this distinct advantage:

If both of the above two criteria are satisfied, the selected optimal trajectory demonstrates a distinct advantage over the do-nothing trajectory. Accordingly, the vehicle executes the corresponding driving maneuver in accordance with the optimal trajectory (e.g., lane keeping with lateral biasing, lane changes).

3.3. Lightweight Trajectory Smoother

Based on the evaluation results, an optimal trajectory is selected. To enhance the drivability of this trajectory, we design a QP-based lightweight trajectory smoother (see [

5]).

First, the feasible solution space for the QP problem is determined. We utilize the vehicle’s kinematic upper and lower bounds to calculate the corresponding bounds of vehicle states at each planning timestamp. Here, the time interval is reduced from 0.25 s to 0.1 s to enhance trajectory smoothness. Within these upper and lower bounds, the optimization reference at each time instant is the original trajectory generated by the planning model. Specifically, the reference values for acceleration and jerk are both set to zero.

At this stage, all necessary elements for formulating the QP problem (as outlined in

Section 2.2) are established, whose main objective is to smooth the trajectory’s longitudinal performance. As detailed in

Section 2.2, the QP optimizer is subject to several constraints: the minimum speed is set to zero, while the maximum speed is constrained by the allowable speed limit; for acceleration and jerk, the ranges are configured to ensure riding comfort.

The output speed profile from QP optimization yields a 6 s smoothed trajectory characterized by high resolution, superior lateral and longitudinal smoothness, and enhanced flexibility.

4. Simulation and Experiments

We validated the effectiveness of the proposed method through both simulations and physical experiments. Two common urban driving scenarios—dynamic obstacle avoidance within intersections and narrow road driving—were selected for testing. In each scenario, we first validated the proposed algorithm via simulations, followed by subsequent physical experiments to further verify its performance.

4.1. Dynamic Avoidance in Intersection

Intersections—especially unprotected ones—are notoriously challenging scenarios for autonomous driving. The ego-vehicle engages in strong dynamic interactions with other road users while maintaining adequate safety margins, which tests the capability of a driving system primarily in terms of safety and efficiency.

4.1.1. Simulation

Our intersection scenario is simulated in a self-developed autonomous driving simulation platform, incorporating all core functional modules required for autonomous driving—including perception, trajectory prediction, ego-vehicle state estimation, planning, and motion control. The simulation operates at a 12 Hz update rate, which fully satisfies the safety-critical requirements for autonomous driving systems. The architecture of the planning framework within the simulation is consistent with that depicted in

Figure 2.

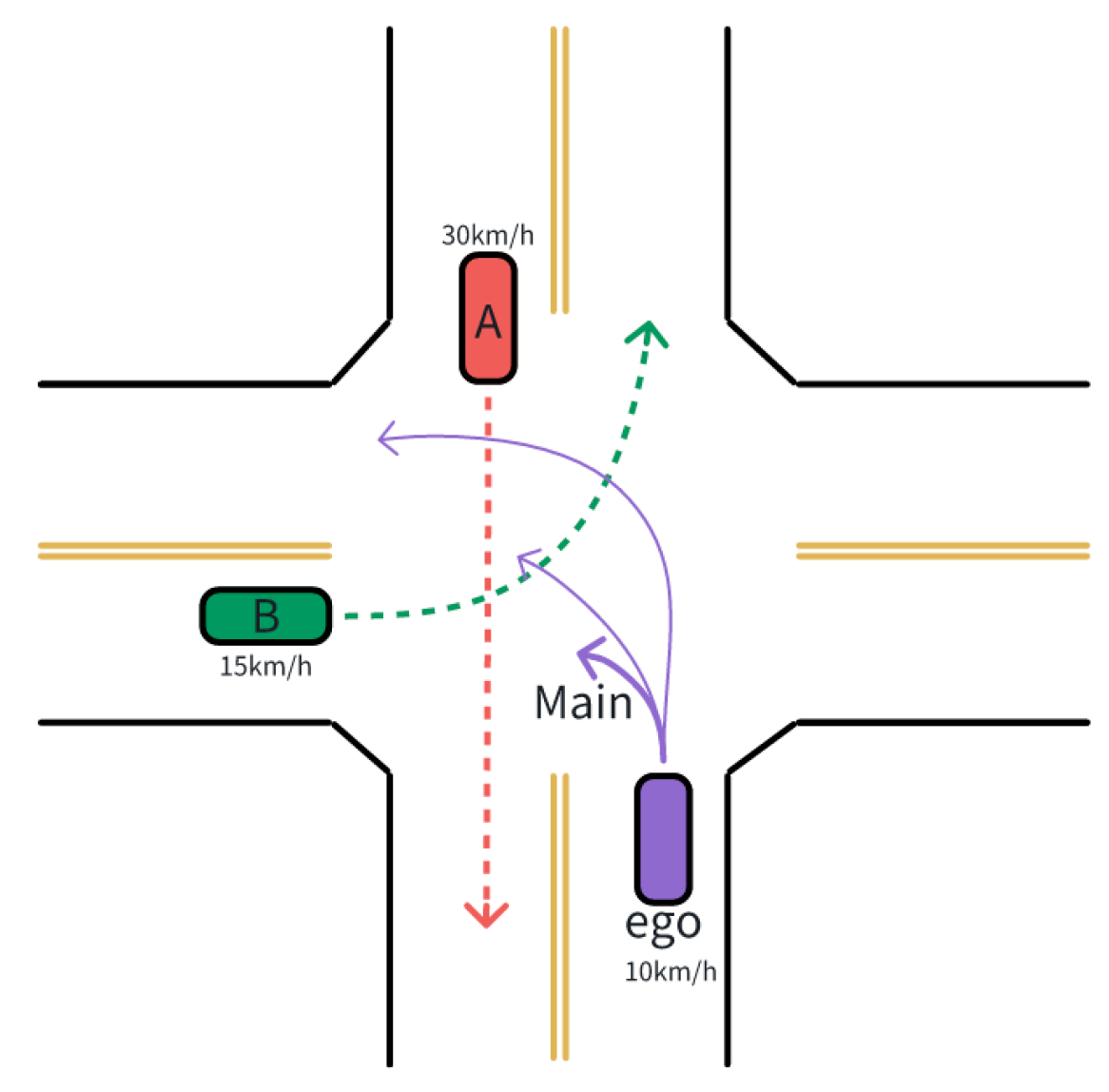

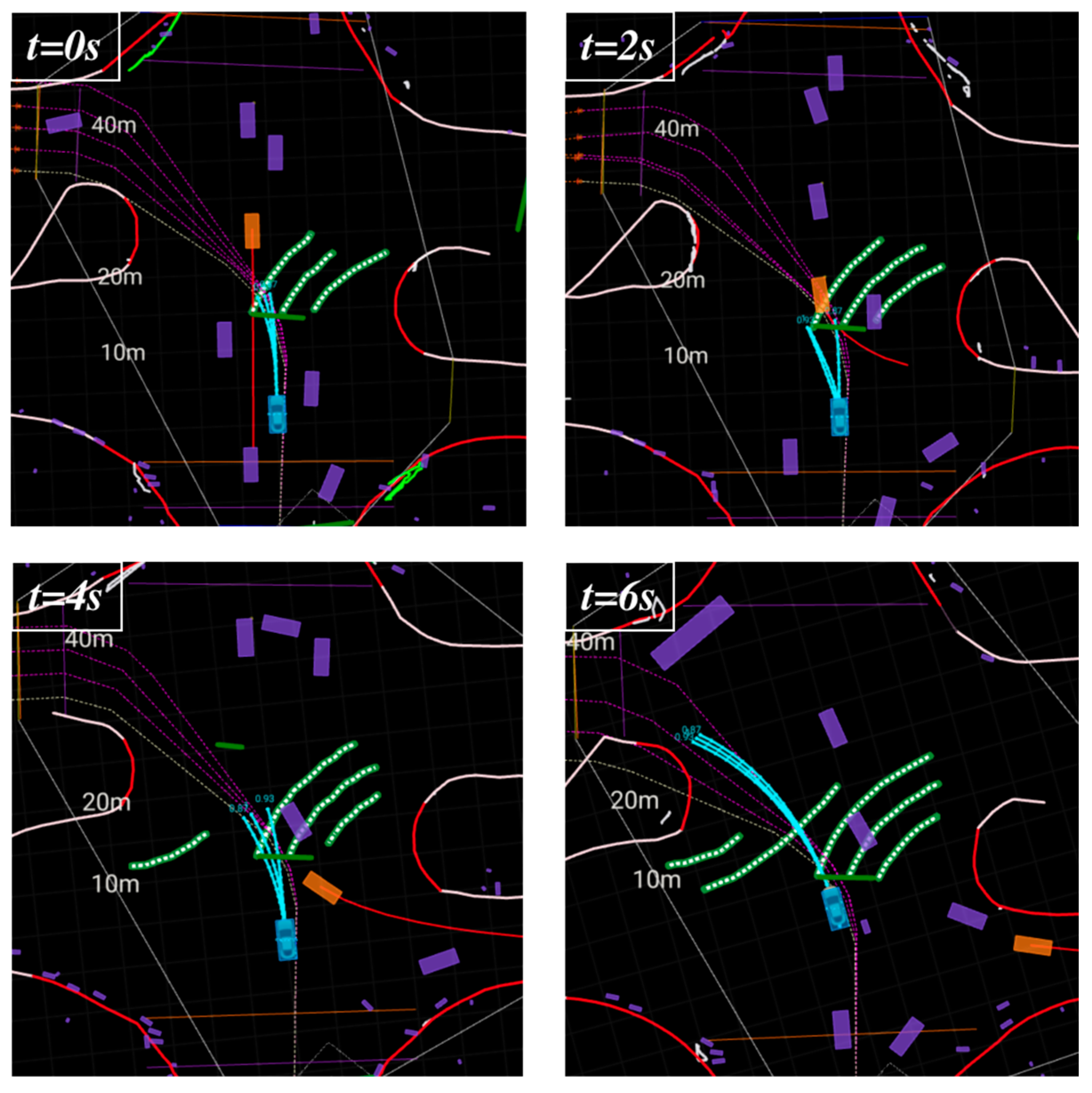

As illustrated in

Figure 6, the scenario considers a fully unprotected, unsignalized intersection where agents from all approach directions may enter freely. The ego-vehicle enters the intersection from the south approach and is tasked with executing a left turn; two concurrent agents are introduced to enter the intersection simultaneously: agent A travels straight, while agent B is also assigned a left-turn maneuver. In this configuration, the ego-vehicle engages in dynamic interactions with both agent A and agent B, resulting in potentially divergent driving strategies. For this scenario, the proposed planning model generates one main trajectory involving yielding to both agent A and agent B. Two auxiliary trajectories are also generated: one overtakes agent B with concurrent yielding to agent A, and the other first proceeds straight to yield to both agent A and agent B prior to executing the left turn.

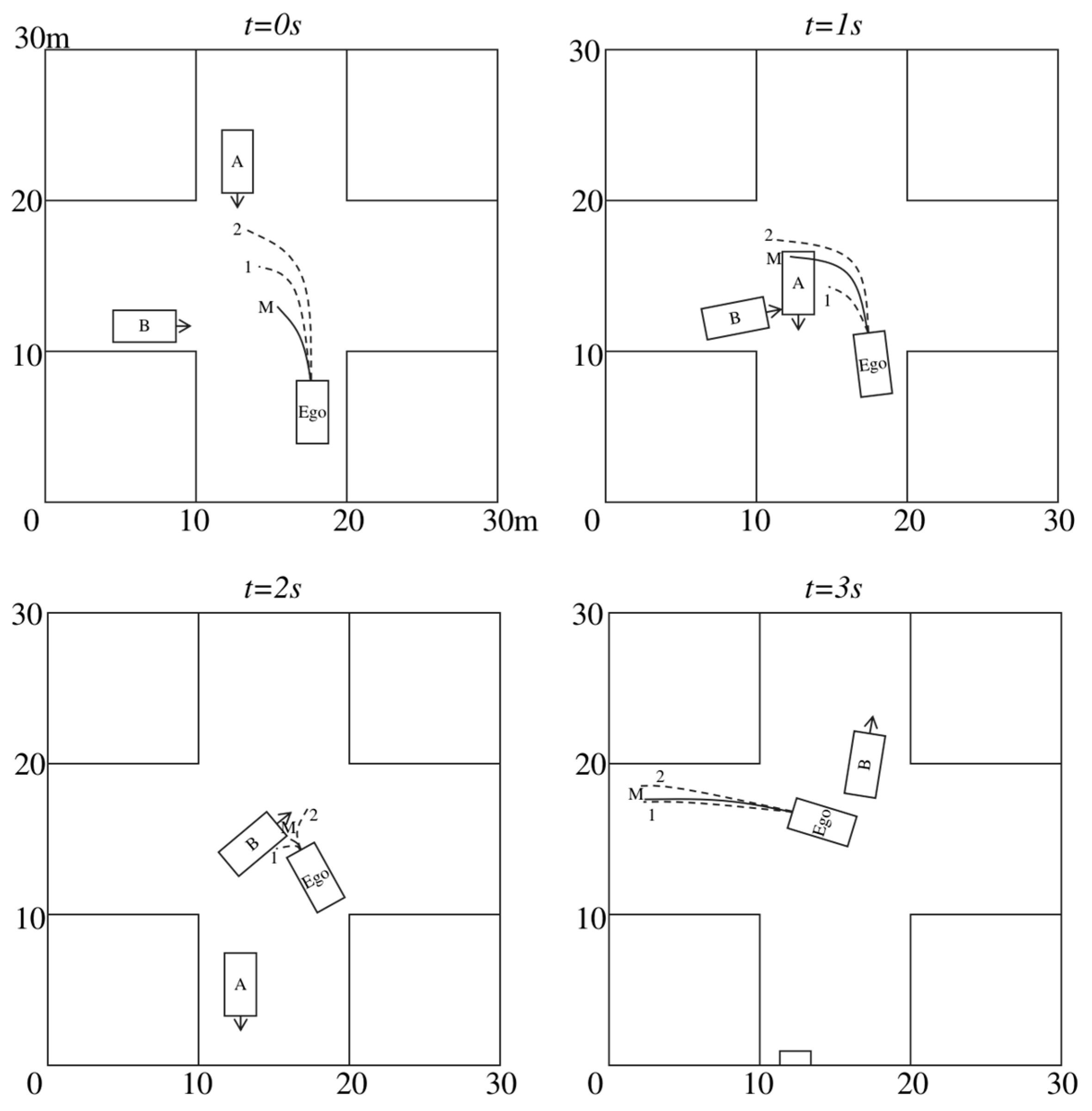

Simulation results are presented in

Figure 7. At the initial time step (t = 0 s), the ego-vehicle and agents A and B enter the same intersection at different speeds. Agent A holds right-of-way and travels at the highest speed. The model’s main trajectory yields to both agents A and B, while the first auxiliary trajectory yields to agent A and overtakes agent B; the second auxiliary trajectory proceeds straight to yield to agent A before overtaking agent B. Through evaluation, the main trajectory exhibits the lowest cost and is thus selected.

At t = 1 s, Agent A enters the intersection. As agent B is blocked by agent A, the model generates a new main trajectory to overtake agent B, whereas the first auxiliary trajectory continues to yield to agent B.

At t = 2 s, the ego-vehicle and agent B encounter each other within the intersection. Given agent B’s superior positional advantage, the ego-vehicle is required to yield to agent B, and all trajectories generated by the model accordingly yield to agent B.

At t = 3 s, the ego-vehicle successfully yields to agent B, begins accelerating, and proceeds to exit the intersection. Throughout the entire process, the main trajectory is consistently selected due to its safety and reasonableness in this complex interaction scenario.

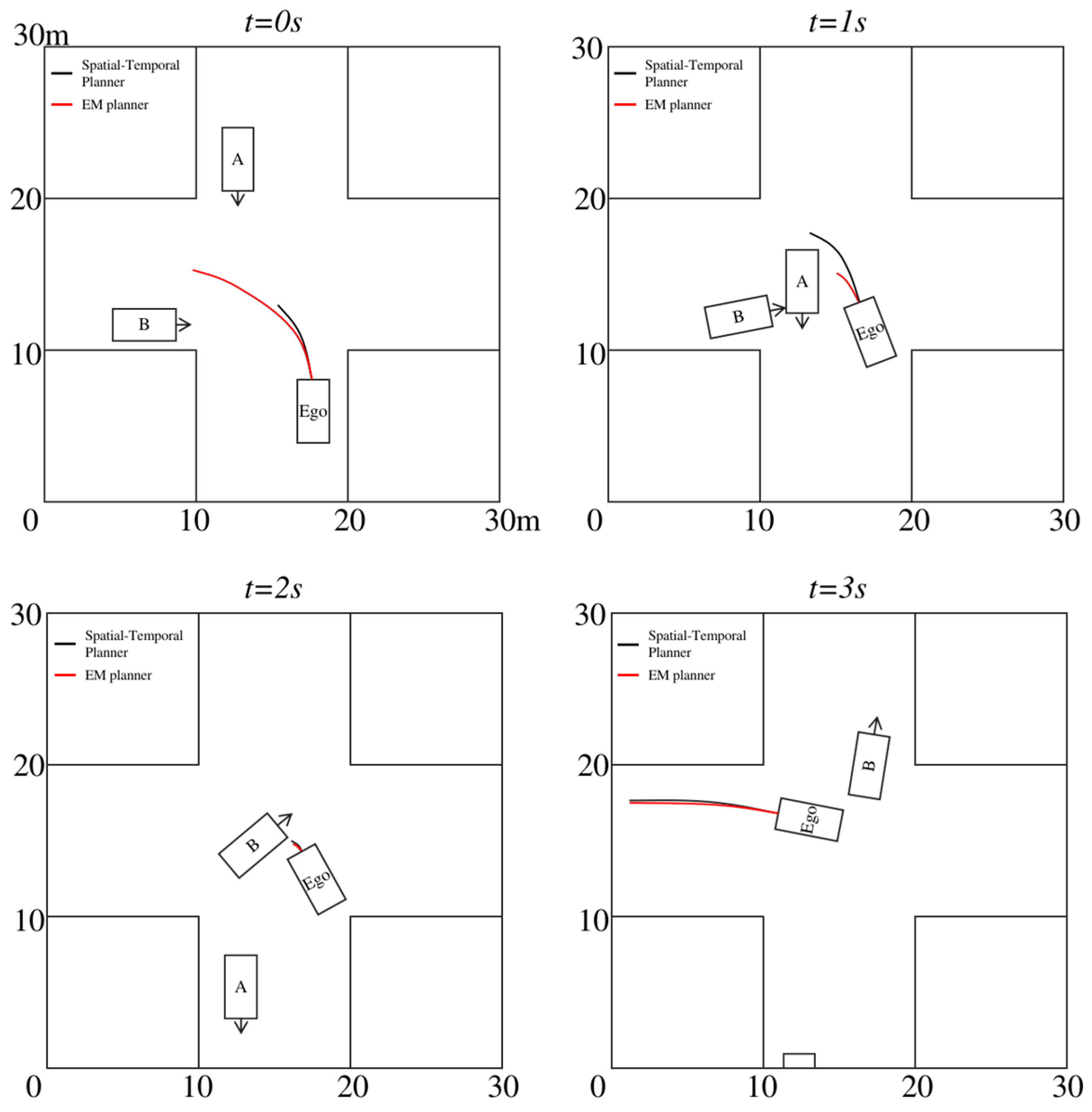

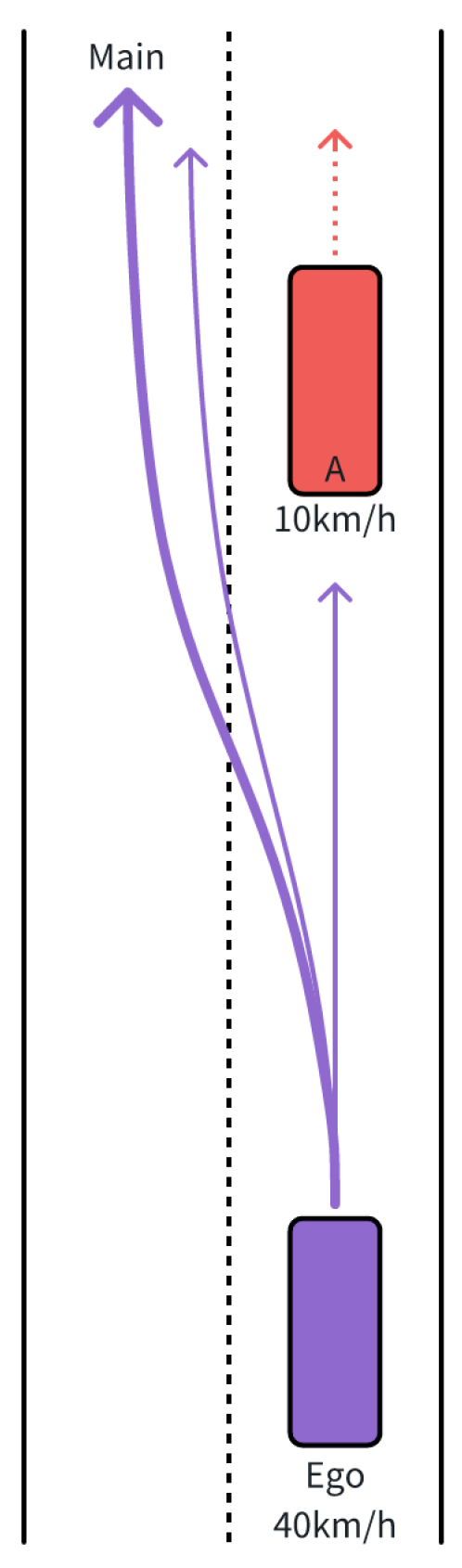

To more intuitively and clearly demonstrate the advantages of the method we adopted, we conducted simulations using the Baidu Apollo EM algorithm in exactly the same environment and compared the simulation results. Since the Baidu Apollo EM algorithm (referred to as EM planner for short) is open-source, we were able to fully reproduce it and adapt it to our own simulation environment, which makes this comparison scientifically valid. As shown in

Figure 8, when facing the same intersection scenario, the EM planner chose to cut in front of vehicle A at the initial stage (t = 0 s), but as vehicle A gradually approached (t = 1 s), it applied heavy braking to yield. Such initially aggressive and then conservative maneuvers significantly reduce driving comfort. By comparing the average deceleration of the trajectories in these two sets of simulations (EM Planner: −1.77 m/s

2, Spatial-Temporal Planner: −1.21 m/s

2), we can verify that the proposed method achieves superior ride comfort. Meanwhile, we can also observe that the trajectory planned by the EM planner for yielding to vehicle A is rather rigid, without human-like backward detouring maneuvers. This will also cause inconvenience for users in practical use. In contrast, the trajectory of the spatio-temporal planner is more human-like and offers higher comfort.

4.1.2. Experiment

The experiment was conducted in an open urban driving environment, with a scenario similar to that of the simulation. The test vehicle is a Xpeng G9 MAX equipped with dual Orin-X SOCs (508 TOPS), two 126-line solid-state lidars, five radars, and twelve ultrasonic sensors. Lane-line detection results, localization data, and sensor fusion outputs are fed to the planning module as inputs. After quantization, our model is converted into a TensorRT (TRT in ARM64 architecture) file, which is then deployed on a single Orin chip together with the overall planning system; another Orin chip is mainly used to deploy algorithms responsible for perception and control tasks. On the dual Orin-X SOCs platform, our entire system can run at a frequency exceeding 15 Hz, with the model’s own latency being approximately 15 ms. An experimental video is provided in

Supplementary Material Video S1.

As illustrated in

Figure 9, the ego-vehicle enters an unprotected intersection and encounters an oncoming vehicle whose driving direction is initially unknown (assumed to travel straight for initialization). The proposed planning model generates three trajectories (represented by blue lines and trajectory points), all of which yield to the oncoming vehicle. Each trajectory is labeled with its probability at the terminal point. As shown in the figure, the main trajectory’s probability remains consistently 1.0, while the probabilities of the two auxiliary trajectories are less than 1.0.

At t = 2 s, as the oncoming vehicle executes a left turn, the main trajectory tends to deviate leftward, whereas the two auxiliary trajectories exhibit conflicting maneuver intentions. Following evaluation, our system selects the main trajectory. At t = 4 s, as the key agent (oncoming vehicle) moves away, the ego-vehicle continuously completes the left turn and then accelerates to exit the intersection. This experiment demonstrates the system’s capability to navigate unprotected intersections under the condition of uncertain intentions of other agents while maintaining reasonable driving efficiency.

4.2. Narrow Road Bypassing

Driving on narrow roads poses significant challenges, as it demands high agility and stable planning capabilities. Slow-moving vehicles and obstructions are the main challenges in narrow road driving scenarios, where bypassing capability is critical. The ego-vehicle must navigate around unpredictable objects while maintaining adequate safety margins; in some cases, it may even need to utilize the opposite lane, which can lead to intense interactions with oncoming vehicles.

4.2.1. Simulation

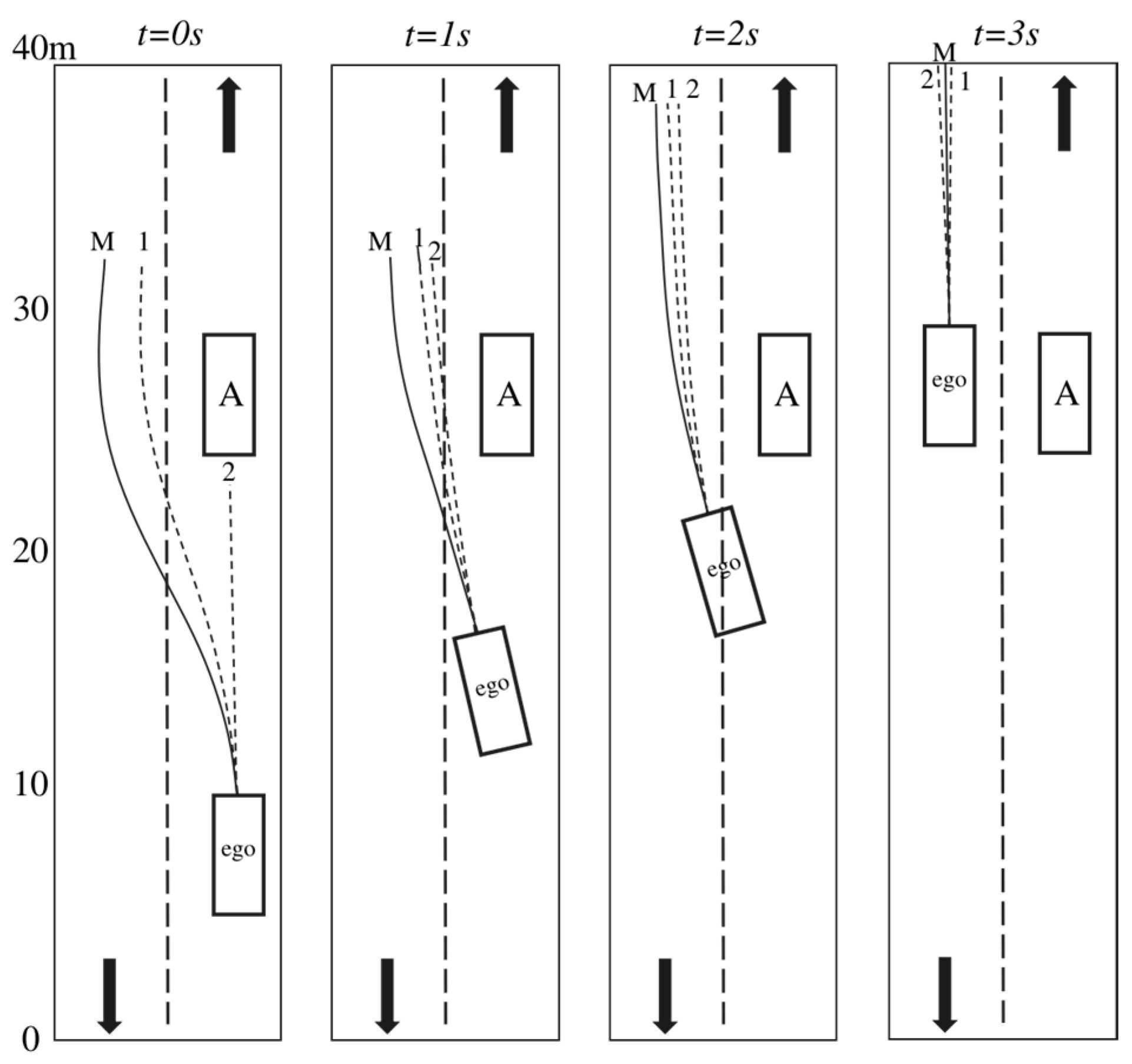

The narrow road bypass scenario is illustrated in

Figure 10. A slow-moving vehicle travels ahead of the ego-vehicle. To bypass this leading slow-moving vehicle (marked as vehicle A), the ego-vehicle needs to utilize the opposite lane and accelerate. As depicted in the figure, the planning model generates multiple trajectories for this scenario: the main trajectory deviates leftward to bypass the leading slow-moving vehicle from the left with adequate safety margins; one auxiliary trajectory performs the same maneuver but maintains a smaller distance from the slow-moving vehicle; the other auxiliary trajectory chooses to follow the slow-moving vehicle while remaining in the original lane.

The simulation results for the narrow-road bypass scenario are illustrated in

Figure 11, where the ego-vehicle detects that the preceding vehicle is traveling at a low speed and initiates an overtaking maneuver. At t = 0 s, the proposed planning model generates three trajectories: one main bypass trajectory, one auxiliary bypass trajectory, and one following trajectory. At this instant, our evaluation system selects the main trajectory, as it achieves the highest efficiency while maintaining adequate safety margins.

After 1 s, with the ego-vehicle’s heading already shifted leftward, all trajectories generated by the model adopt the same bypass maneuver. The evaluation system then selects the safest option, namely the main trajectory. At t = 2 s, the main trajectory is retained to ensure lateral stability. At t = 3 s, once the ego-vehicle successfully overtakes vehicle A, the main trajectory—configured to proceed straight—continues to be selected.

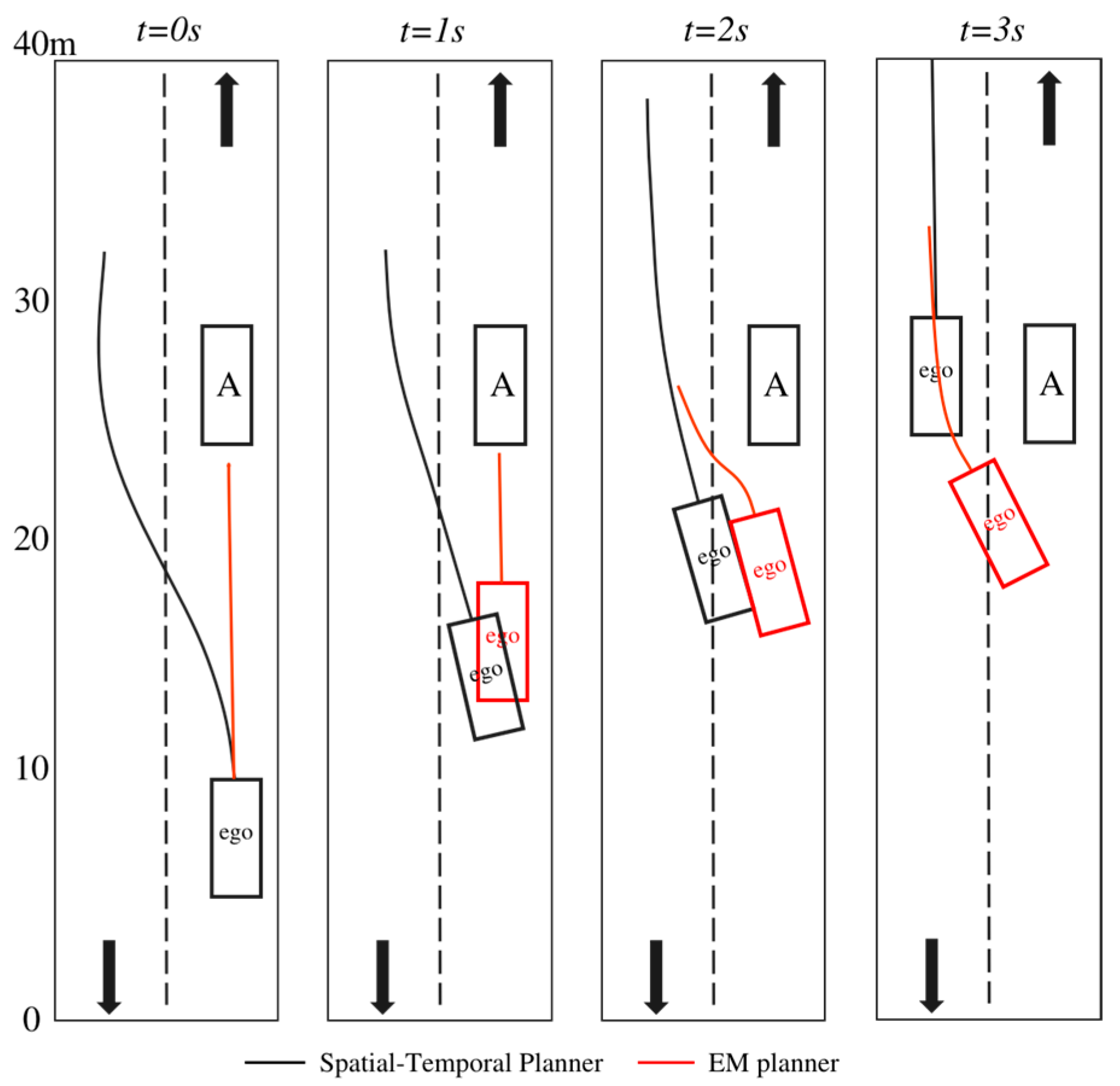

Similarly, we also compared with the EM planner in this scenario, and the results are presented in

Figure 12. Due to the EM planner’s strong reliance on its decision state machine, it failed to make a timely bypass decision in the initial stage and could only reduce speed to follow the preceding vehicle. After a period of time, the decision state machine reached the threshold and triggered the bypass; however, the bypass maneuver at this point required a larger lateral range, and the speed had dropped to a low level, resulting in a loss of efficiency. The overall behavior is also not human-like. In contrast to the EM planner, the trajectories generated by our method are superior to those of the EM planner in terms of bypass timing and maneuvers, improving efficiency and ride comfort. By comparing the bypass time and average lateral acceleration in these two sets of simulations (EM Planner: bypass time = 4.8 s, lateral acceleration = 0.81 m/s

2; Spatial-Temporal Planner: bypass time = 3.3 s, lateral acceleration = 0.39 m/s

2), we can quantitatively verify this superiority.

4.2.2. Experiment

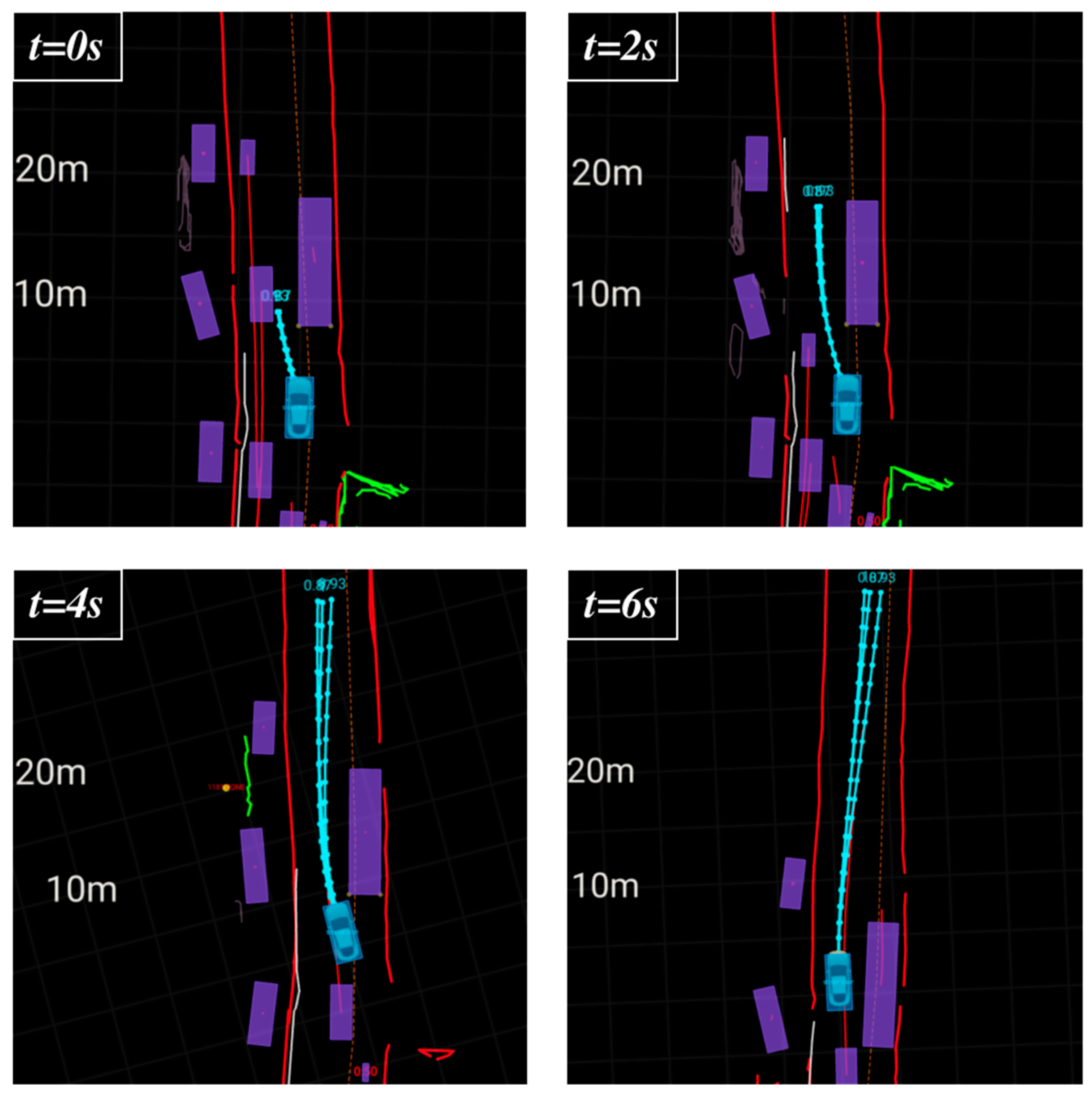

The experiment was conducted on an open urban narrow road with a single lane in each direction. As illustrated in

Figure 13, the ego-vehicle detected a bus stopped with its emergency lights activated ahead; the proposed model’s default response was to utilize the left opposite lane to bypass the bus. At t = 0 s, the main and auxiliary trajectories exhibited consistent maneuver intentions. However, the left opposite lane was occupied by oncoming vehicles, so all generated trajectories maintained a low speed to ensure safety.

At t = 2 s, as the oncoming vehicles gradually passed, the trajectories generated by the model began to accelerate. At t = 4 s, with the opposite lane fully clear for travel, the trajectories continued to accelerate. At t = 8 s, the ego-vehicle successfully bypassed the stopped bus and slowly merged back into its original lane.

Throughout the entire process, since the main and auxiliary trajectories demonstrated nearly identical efficiency, the spatio-temporal evaluation focused primarily on lateral stability between frames—ultimately favoring the selection of the main trajectory. This result verifies that the main trajectory generated by the proposed model performs effectively in this scenario. The experimental video is provided in

Supplementary Material Video S2.

In addition to these two scenarios, since our system has been successfully mass-produced, we have also collected more generalized test metrics. These metrics are compiled from tests conducted by our test fleet across different cities, mainly including: the number of hard brakes per 100 km (a measure of comfort), the number of unreasonable steering wheel oscillations per 100 km (a measure of lateral stability), the average speed in urban scenarios (a measure of efficiency), and the number of safety takeovers per 100 km (a measure of safety). The statistical data presented in

Table 2 were collected between July and August 2025, with a total mileage exceeding 20,000 km.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, a learned planning model-based spatio-temporal decider is proposed. To generate multi-modal trajectories, a dedicated planning model is designed, with details of its architectural design and training dataset presented herein. Subsequently, a spatio-temporal evaluation framework is developed to select the optimal trajectory from the candidate trajectories output by the planning model.

This work demonstrates exceptional practical efficiency, as it integrates the high-performance advantages of data-driven approaches while ensuring stable operational performance through the proposed spatio-temporal evaluation mechanism. The significance of the proposed method lies in two key aspects: theoretically, the learned planning model-based framework exhibits strong extensibility, allowing for multiple structural modifications to support diverse decision-making tasks or combined decision strategies in complex driving environments. Practically, the method can be seamlessly deployed on most autonomous driving platforms without requiring additional computational resources.

Comprehensive simulations and real-world experiments have thoroughly verified the effectiveness of the proposed method. Notably, this work has been successfully integrated into thousands of mass-produced vehicles currently in road operation. Future research will focus on enhancing the model’s performance and optimizing the evaluation process to improve its simplicity and efficiency.