1. Introduction

Propeller blades serve as fundamental elements in both manned and unmanned aerial platforms, where their dynamic behavior directly impacts aerodynamic performance, acoustic signature, and structural resilience. Accurate characterization of blade vibration modes is essential to prevent resonance, reduce noise emissions, and ensure long-term reliability under varying operational loads. Conventional design paradigms employ high-fidelity finite element analysis in conjunction with computational fluid dynamics to resolve complex fluid–structure interactions and compute natural frequencies. While these techniques yield precise modal predictions, they demand extensive computational resources and lengthy runtimes, thereby constraining the number of design iterations and inhibiting real-time decision making during early-stage development.

The emergence of machine learning algorithms provides a compelling avenue for constructing surrogate models that replicate numerical simulation outputs at a fraction of the computational cost. By learning the relationships among blade geometry, material properties, boundary conditions, and vibratory response, data-driven frameworks can execute thousands of design evaluations in near real time. Such accelerated analyses enable comprehensive exploration of design spaces, support uncertainty quantification, and facilitate integration into optimization loops and digital twin environments. Despite growing interest in surrogate modeling for turbomachinery components, the application to propeller vibration remains relatively unexplored, particularly in capturing higher-order modes and complex boundary effects.

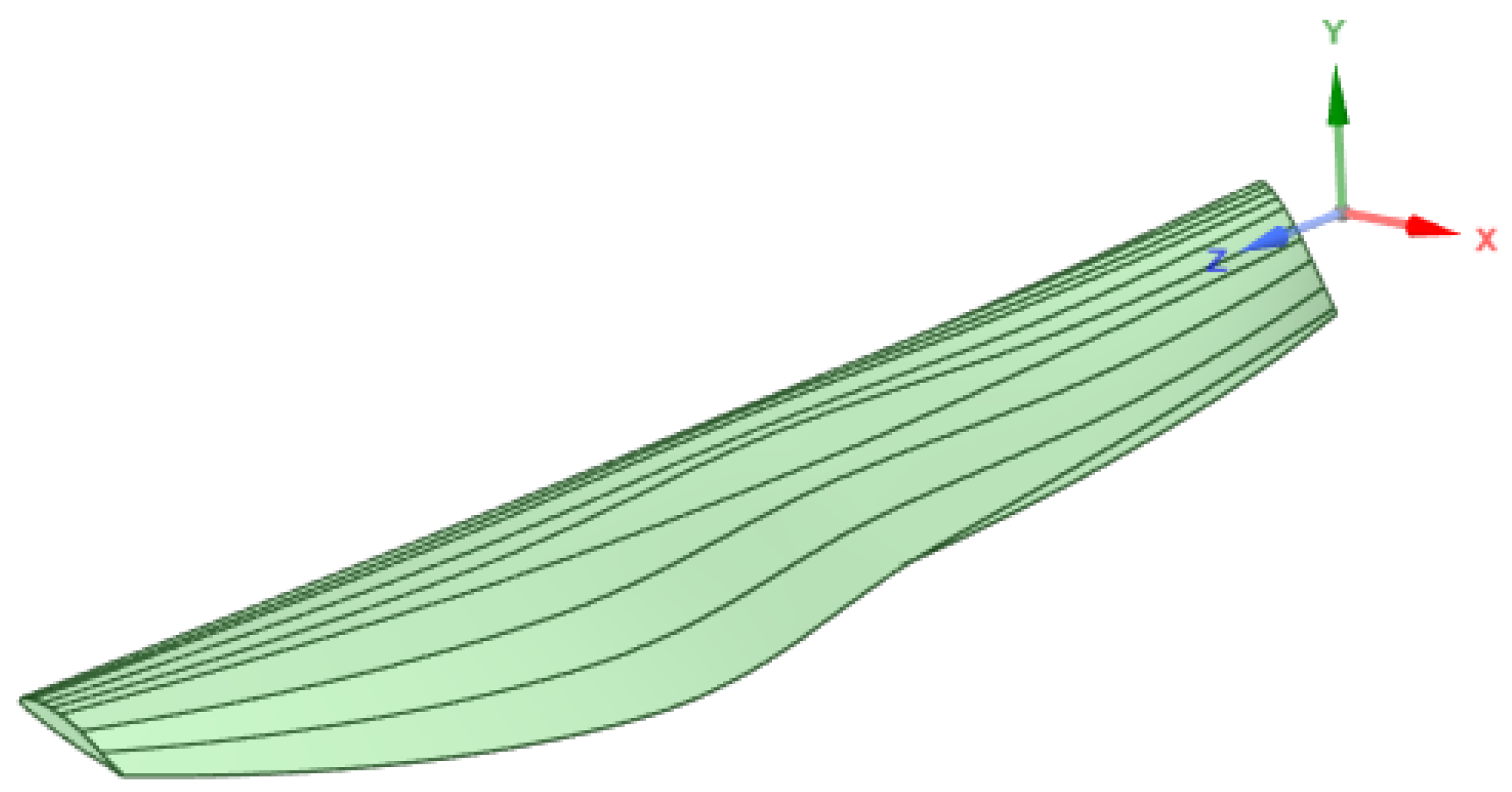

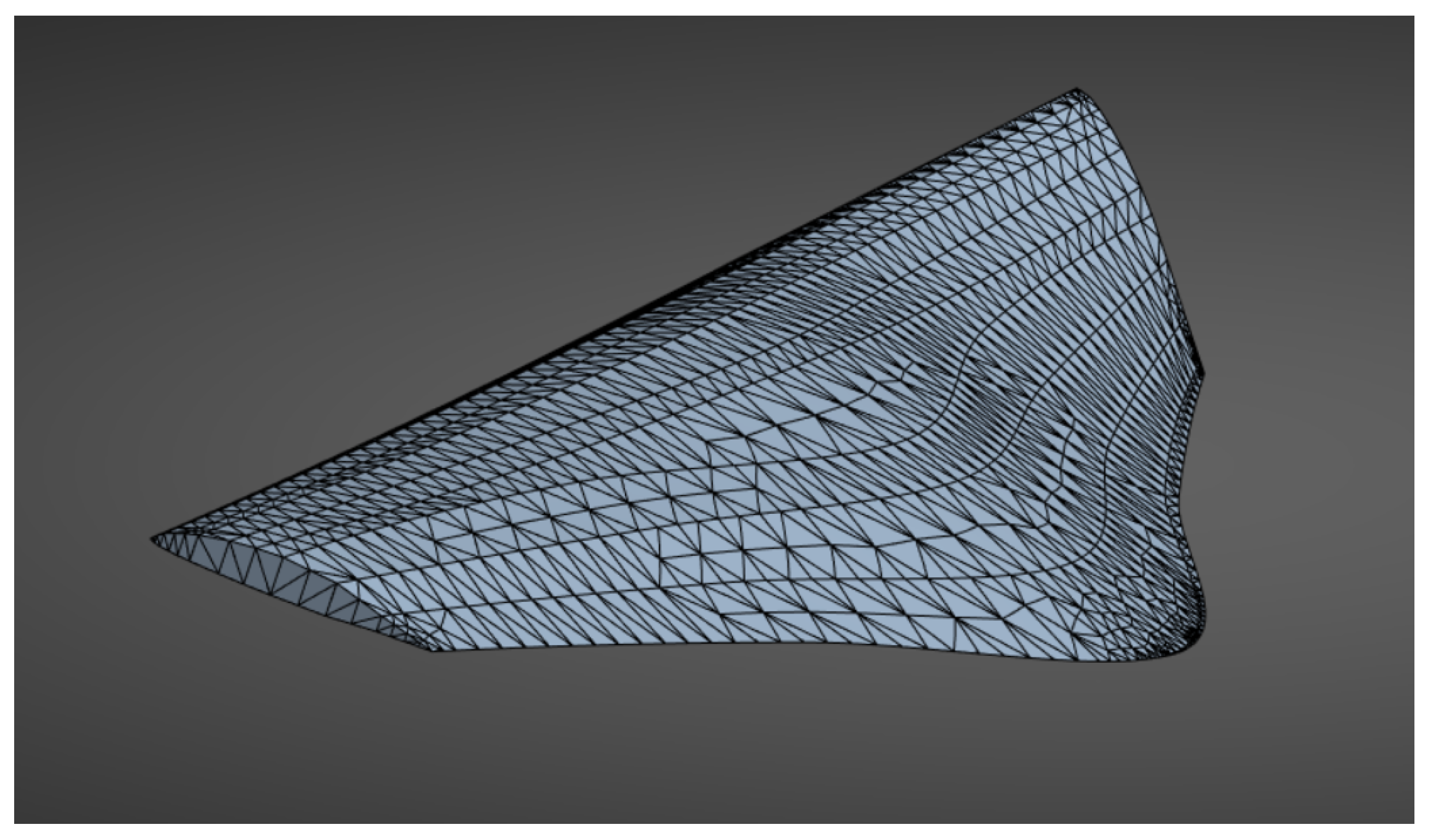

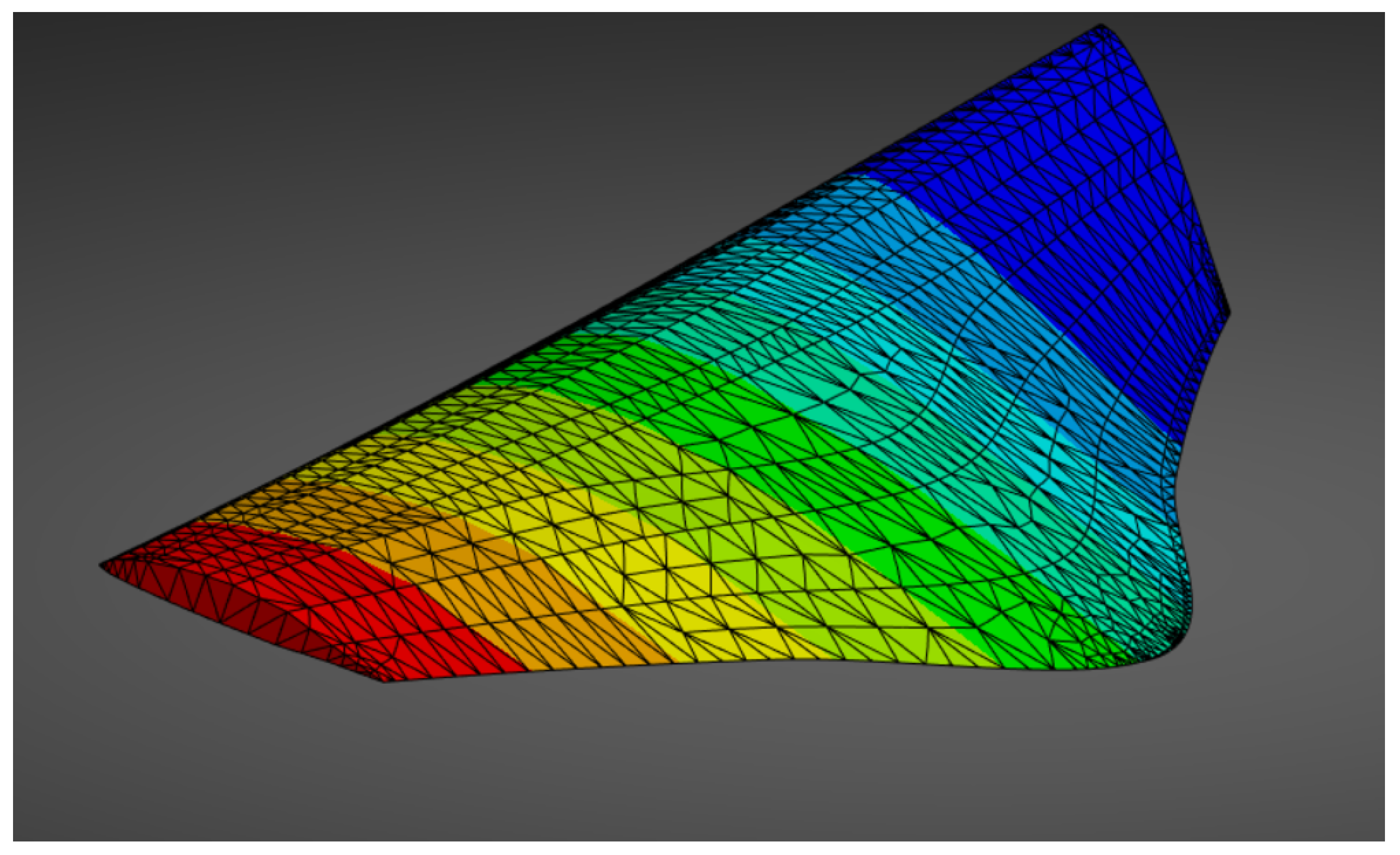

This study introduces a systematic framework for predicting the natural vibration frequencies of propeller blades using a feedforward neural network. A database of 1364 distinct airfoil geometries was generated and subjected to modal analysis in ANSYS under a variety of rotational speeds and boundary constraints to produce a comprehensive training set. The airfoil database was obtained from the UIUC Airfoil Database [

1], and thin and exotic airfoils were removed. A TensorFlow/Keras model was then trained and optimized through randomized search cross-validation across network depth, neuron counts, learning rate, batch size, and optimizer selection. The resulting surrogate model achieves a high coefficient of determination and low normalized root mean square error for the second and higher-order modes, while reducing prediction time by several orders of magnitude compared to full finite-element workflows.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides a review of related work on machine learning in rotorcraft and propeller design.

Section 3 provides the materials and methods, and describes the data generation pipeline, including geometry parametrization and simulation setup.

Section 4 details results and discussion. Finally,

Section 5 concludes with a summary of contributions and outlines future resarch directions aimed at further enhancing surrogate model fidelity and generalization.

2. Literature Review

The application of machine learning (ML) and computational methods has significantly advanced propeller and rotorcraft design, optimizing performance, reducing noise emissions, and improving structural stability. Across various studies, researchers have explored different methodologies to enhance efficiency, aerodynamics, and acoustic properties in aerospace, marine, and unmanned systems.

Recent advances in deep learning have reignited interest in data-driven simulation of physical systems [

2]. Deep neural networks (DNNs) excel at learning intricate nonlinear mappings when supplied with abundant, high-fidelity data, enabling accurate outcome prediction purely from observed inputs [

3]. Fundamentally, this data-driven approach relies entirely on neural networks inferring the system’s inherent dynamics from raw observations, without any explicit incorporation of the governing physical laws [

4,

5]. However, their performance degrades markedly under conditions of data sparsity or excessive noise, leading to poor generalization and unreliable extrapolation [

6].

One branch of research addresses this limitation by constructing purely data-driven surrogate or reduced-order models using vast volumes of experimental or computational data [

7,

8]. While these surrogate models can achieve impressive accuracy, they often neglect fundamental physical constraints, behaving as opaque “black boxes” that may violate conservation laws and demand extensive data acquisition and careful experiment design, which can be computationally and logistically expensive [

9].

A complementary paradigm embeds known physics directly into the training of DNNs, giving rise to physics-informed or physics-constrained neural networks [

10,

11,

12]. By incorporating governing equations (e.g., partial differential equations) into the loss function, these networks can produce accurate solutions even with scarce or unlabeled data [

13]. The imposed physical constraints act as a regularizer, mitigating overfitting, reducing dependence on large datasets, and enhancing predictive robustness by enforcing adherence to fundamental laws throughout learning [

14].

Several studies apply machine learning techniques to optimize propeller design for improved aerodynamic efficiency, structural stability, and sustainability. Doijode et al. [

15] utilized orthogonal parametric modeling and clustering algorithms to identify key design-variable correlations that enhance propeller performance while reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Their explainable ML models, validated using silhouette scores and Gaussian process regression (GPR), align well with experimental data, though limitations remain in capturing non-conformal geometry modifications and blade-hub interactions. Vardhan et al. [

16] proposed the PropDesigner framework, integrating random forest regression (RF) with evolutionary algorithms to identify high-efficiency geometries. By achieving up to 90% efficiency compared to 50% in conventional designs, the study highlights the potential of hybrid ML-evolutionary approaches and suggests neural network integration and high-fidelity simulations for future refinement.

Structural analysis and material optimization further support performance improvements. Ahmad et al. [

17] used finite element analysis (FEA) to evaluate quadcopter propellers made of carbon fiber-reinforced polymer (CFRP), identifying configurations with high resonance frequencies (183–1352 Hz) and minimal deformation. Similarly, Kilikevicius et al. [

18] explored aeroelastic effects in flexible fiberglass propellers, demonstrating up to 2.2% speed gains through improved resonance alignment with operational ranges. Dahal et al. [

19] focused on high-altitude UAV applications, optimizing fixed-pitch aluminum alloy propellers via blade element theory (BEM) and validating designs through computational fluid dynamics CFD and experiments. Structural integrity and modal safety are confirmed through stress and vibration analyses, despite observed discrepancies in thrust due to test-environment variations.

Acoustic prediction and noise mitigation are critical for both aerial and marine applications. Li and Lee [

20] developed a framework using artificial neural networks (ANNs) and linear regression for broadband noise prediction in urban air mobility (UAM), with ANNs significantly outperforming traditional solvers in speed and frequency-domain accuracy. However, model opacity and simplified parameter interactions remain challenges. Legendre et al. [

21] integrated CFD and computational aeroacoustics simulations with regression models such as gradient boosting regression (GBR) and random forest (RF) to enable real-time noise spectrum prediction for UAVs. Their system includes a graphical interface that assists in evaluating rotor speed effects on noise profiles, with results consistent with experimental benchmarks. In the marine domain, Xie et al. [

22] developed a semi-analytical vibro-acoustic model of submarine propeller-shaft-hull systems, achieving high accuracy and computational efficiency by replacing traditional FEM/BEM techniques. The study reveals that breathing modes dominate acoustic radiation and that bearing stiffness significantly impacts vibro-acoustic behavior.

Advancements in surrogate modeling and optimization have also improved marine propeller design. Uslu et al. [

23] introduced a frequency reduction ratio for modal analysis in water, enhancing the accuracy of fluid-structure interaction models under submerged conditions. Gypa et al. [

24] presented an interactive optimization system combining genetic algorithms and support vector machines (SVMs), incorporating human input to balance cavitation risks and performance. The SVM surrogate model effectively reduces manual evaluation needs while improving design iteration efficiency.

Recent research has increasingly incorporated physics-informed and federated learning paradigms. Soibam et al. [

25] proposed an ensemble physics-informed neural network (PINN) framework for inverse flow and thermal field reconstruction. By embedding the Navier–Stokes and energy equations in the loss function and enforcing optimal sensor placement, they achieve sub-10% relative errors with high uncertainty quantification and robust performance from minimal sensor data. Similarly, Vermelin et al. [

26] applied federated learning (FedAvg, FedPer) with long short-term memory (LSTM) and ConvGRU architectures for remaining useful life (RUL) prediction across non-IID datasets. Their privacy-preserving approach matches or exceeds local baselines on SiC-MOSFET and turbofan benchmarks, with minimal degradation under realistic network constraints. The study suggests applicability to distributed propeller-blade data without violating data governance.

Emerging diagnostic and decision-support systems further expand ML’s role. Soibam et al. [

27] achieved high-precision (96% AP at IoU = 0.5) bubble segmentation in two-phase flows using a CNN-based instance segmentation model (YOLOv7 + YOLACT++), leveraging transfer learning and demonstrating robustness to noise and dynamic phenomena. Their pipeline extracts localized geometric statistics with minimal error, offering parallels to propeller-blade vibration modeling, where such descriptors could enhance low-cost ML predictions. Mählkvist et al. [

28] introduced a cost-sensitive classification framework for industrial batch processes, using confidence thresholds and relative cost matrices to balance accuracy and deployment cost. Their approach reduces relative operational risk by up to 74% compared to baseline and illustrates potential trade-offs between prediction certainty and simulation effort in propeller design workflows.

Netzell et al. [

29] offered a comprehensive methodology for input derivation and validation in time-series forecasting. By applying rolling-origin evaluation, MSTL decomposition, and lag-matched training, they reduce RMSEs significantly for electric-load prediction. Their protocol, emphasizing rigorous feature selection and retraining cadence, serves as a model for structuring inputs in propeller frequency prediction, balancing model accuracy and computational efficiency.

The present work proposes an automated end-to-end CAD/CAE to machine learning pipeline that makes high-fidelity modal prediction for propeller blades practical within design time frames. It explicitly incorporates rotational effects in the modal simulations and assembles a large and diverse multi-profile simulation corpus to train data-driven surrogates. Through a careful and systematic benchmark across different families of learning algorithms, the work shows that trained surrogates can reach high predictive accuracy while substantially reducing the time needed to obtain modal estimates compared with full finite element analysis, and that different model families display complementary strengths depending on the frequency band. The work is innovative in integrating an automated CAD and CAE workflow, explicit treatment of rotational modal effects, a broad multi-profile simulation corpus, and a comprehensive comparison of machine learning methods to produce rapid and accurate modal surrogates for propeller blades, thereby closing the gap between high-fidelity analysis and time-limited design practice.

In summary, advancements in ML, computational modeling, and optimization techniques have significantly improved propeller and rotorcraft design across various domains. These studies collectively underscore the importance of integrating data-driven approaches with traditional engineering methodologies to achieve sustainable, high-performance solutions, paving the way for future innovations in aerospace, marine, and UAV applications.

The novelty of this study lies in the integration of an automated CAD–CAE pipeline with machine learning to predict the natural frequencies of rotating propeller blades across a wide design space. Unlike existing studies that rely on limited geometries or simplified physics, this work combines a large and diverse airfoil database with fully automated ANSYS modal analyses that include rotational effects. In addition, a systematic comparison of multiple machine learning models is conducted using a consistent training and evaluation protocol, demonstrating the suitability of machine learning models as accurate for both low- and high-order modal predictions.

4. Results and Discussion

In this section, we present a comprehensive evaluation of the four regression algorithms: Gaussian process regression (GPR), gradient boosting (GB), neural network (NN), and random forest (RF) across ten vibrational modes. The goal is to quantify each model’s ability to predict the modal frequencies from the provided feature set as the size of the training dataset varies. Two complementary performance metrics are employed—the coefficient of determination (), which measures the model’s ability to explain the variance in the target, and the normalized root-mean-square error (NRMSE), which captures the prediction error relative to the observed range.

For each mode, we incrementally increase the number of training samples from 500 up to 2000 and record both and NRMSE. This allows us to analyze learning curves that reveal (i) the data efficiency of each algorithm, (ii) its convergence behavior, and (iii) its robustness across low, mid, and high-frequency regimes.

The machine used for the simulations and model training was an Intel Core i7 11800H (2.30 GHz) with 32 GB of RAM. Parallel processing was employed when possible. The CAE simulations to obtain natural frequency data took approximately 360 h. Each model training run required roughly 0.5 to 3 h, depending on the model and hyperparameter settings. While a single CAE simulation took around 10 min, the data-driven models took around 0.05–0.5 s to predict the natural frequencies,

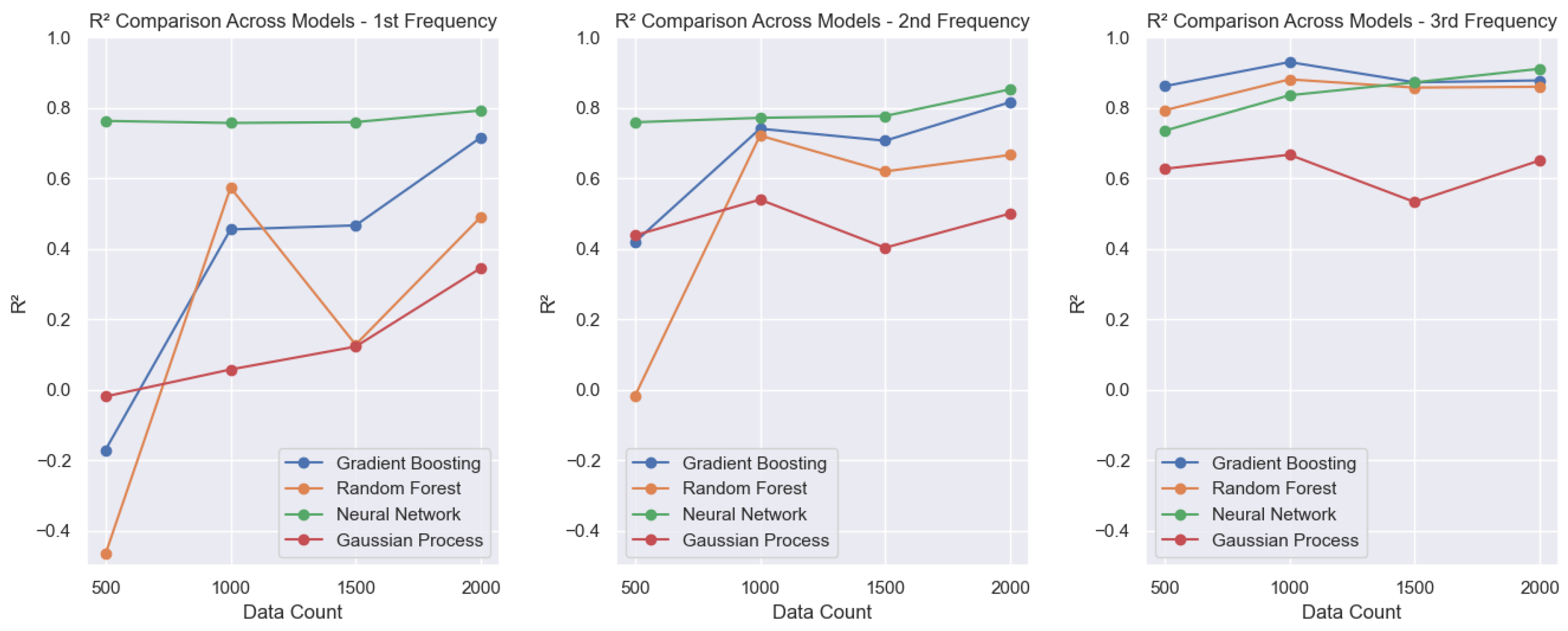

4.1. Coefficient of Determination (R2)

This section presents the analysis of the coefficient of determination () for the evaluated models across different vibrational frequencies. The metric measures the proportion of variance in the target variable that is predictable from the input features, providing an overall indication of the model’s accuracy. The following figures illustrate how evolves as the size of the training dataset increases, offering insights into the learning behavior and performance scalability of each model.

For the first three vibrational modes (

Figure 5), all four algorithms exhibit a clear improvement in the coefficient of determination (

) as the training set size increases. The neural network (NN) model already achieves

values close to 0.8 even with the smallest training set, showing steady improvements as more data becomes available. In contrast, for the first vibrational frequency, the GPR, gradient boosting (GB), and random forest (RF) models present poor performance, with

values reaching negative levels when trained with only 500 samples. As the dataset grows, GB shows a notable improvement, reaching an

of approximately 0.7, while RF and GPR remain with unsatisfactory

scores. For the second frequency, GB continues to outperform, achieving an

of around 0.8, whereas RF and GPR still underperform. In the case of the third frequency, only the GPR model maintains a comparatively lower performance, with

values of around 0.6, while the other models perform considerably better.

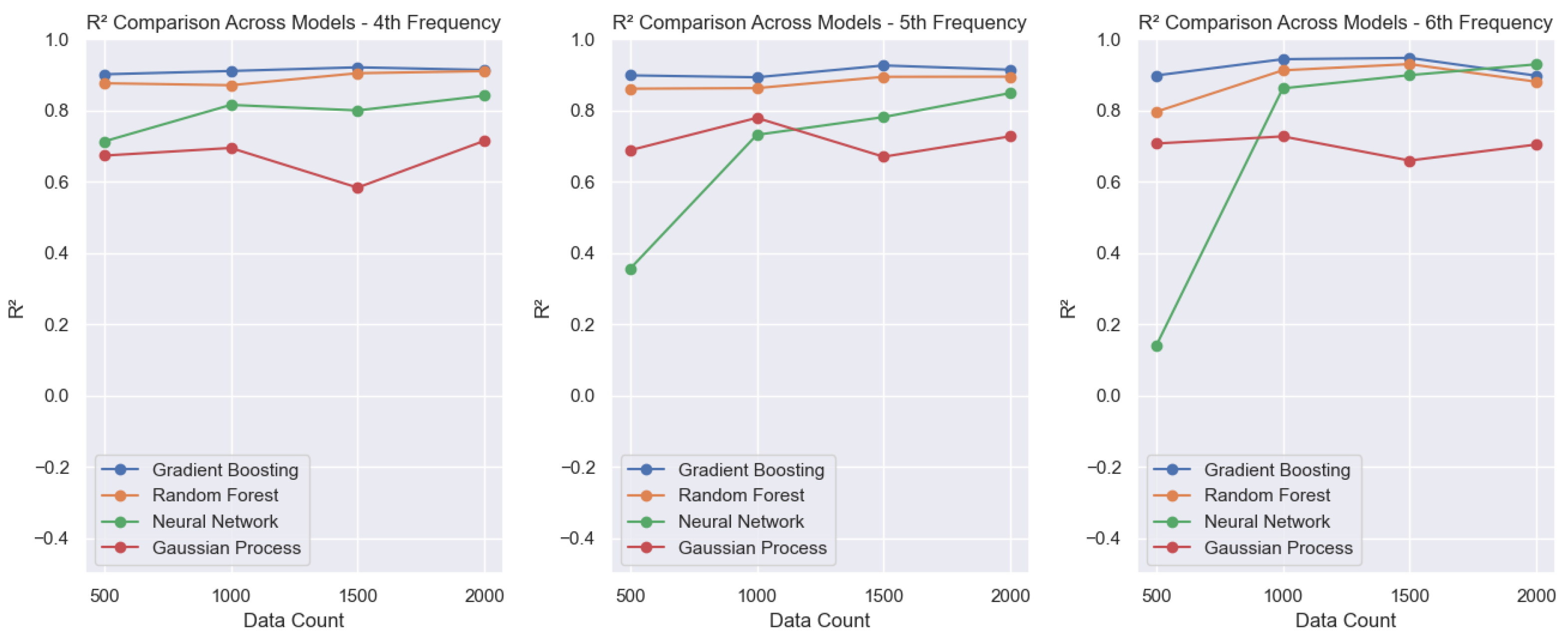

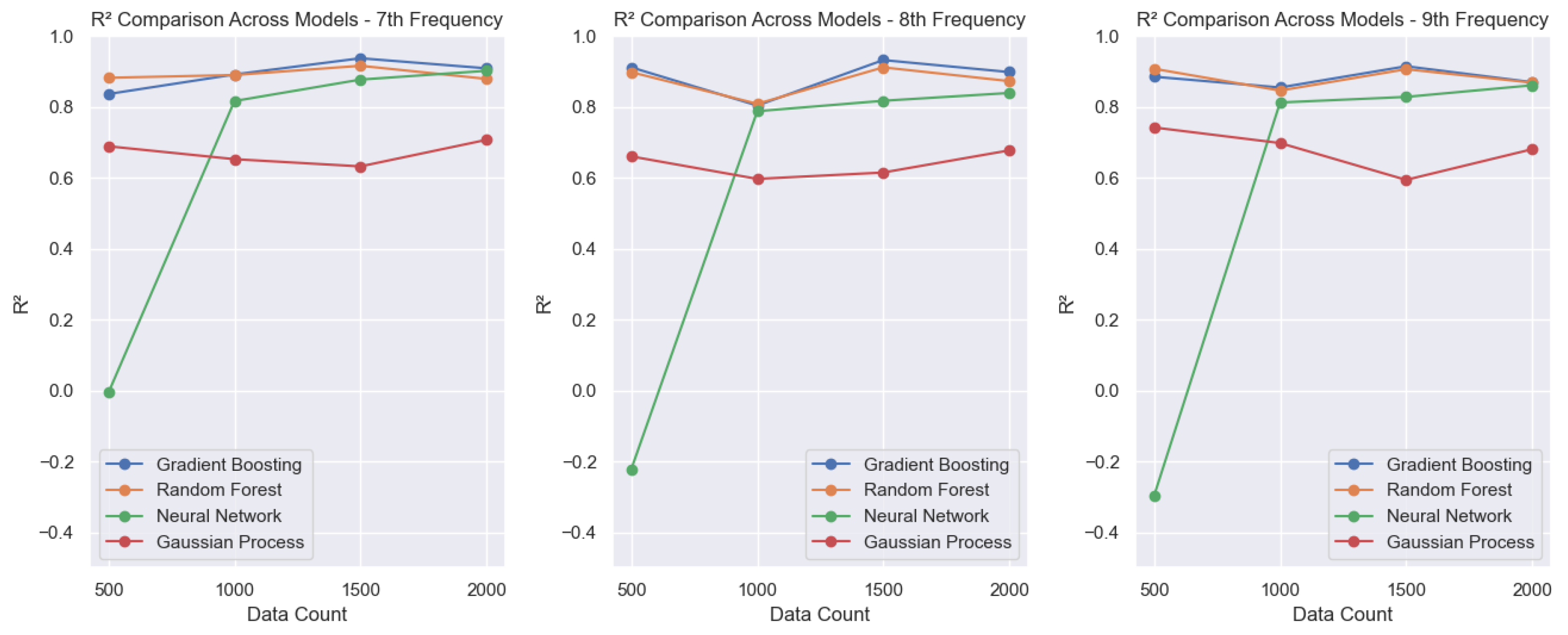

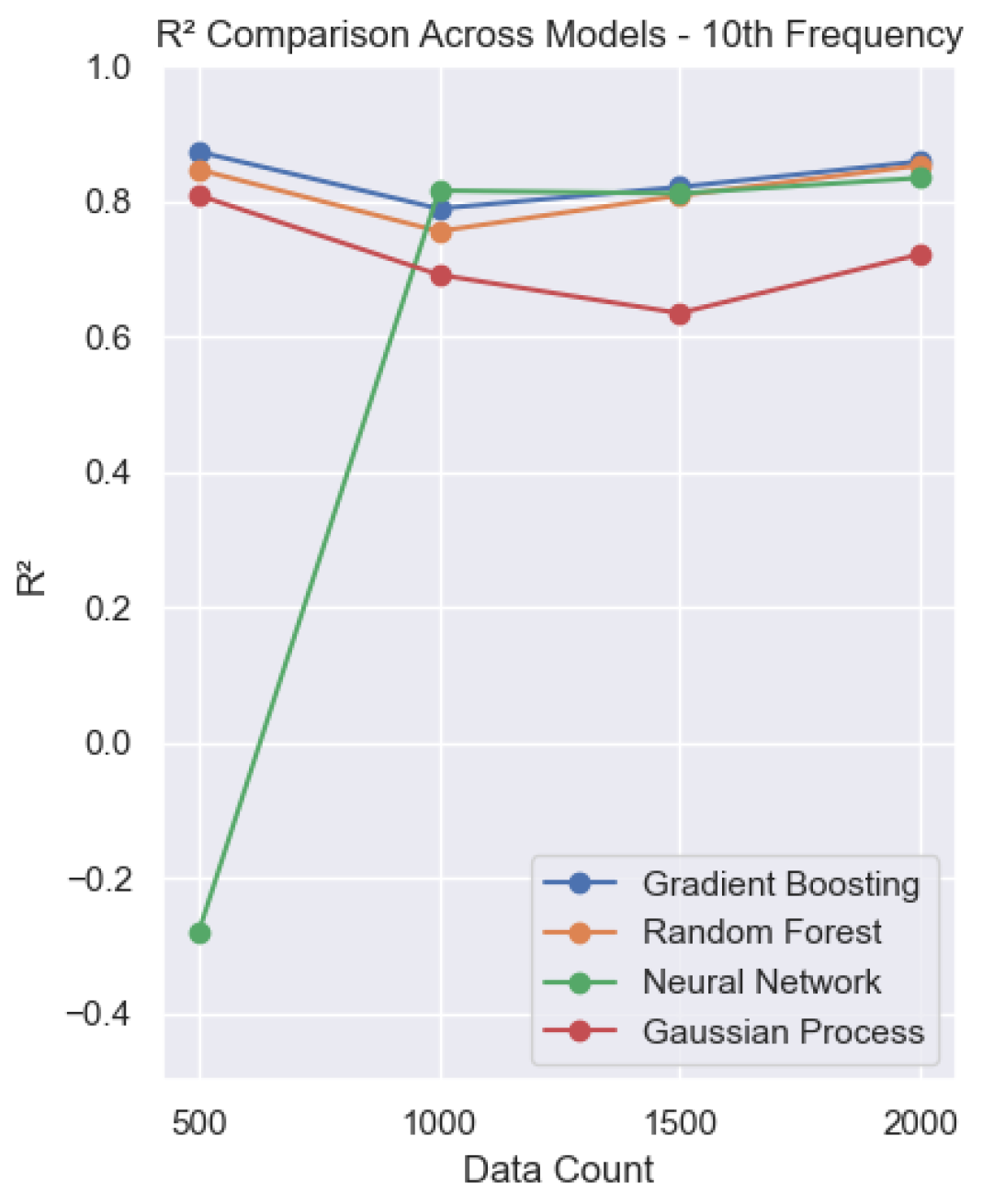

For the higher frequencies (4th–10th modes,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8), the neural network initially exhibits systematically low

values when trained with the smallest dataset. This effect becomes more pronounced as the frequency increases. However, as the training set grows, the NN model improves significantly, reaching

values of around 0.9. In these modes, both GB and RF show consistent and strong performance, with

values typically ranging from 0.8 to 0.9. Conversely, the GPR model continues to underperform relative to the others, with

values varying between 0.6 and 0.8.

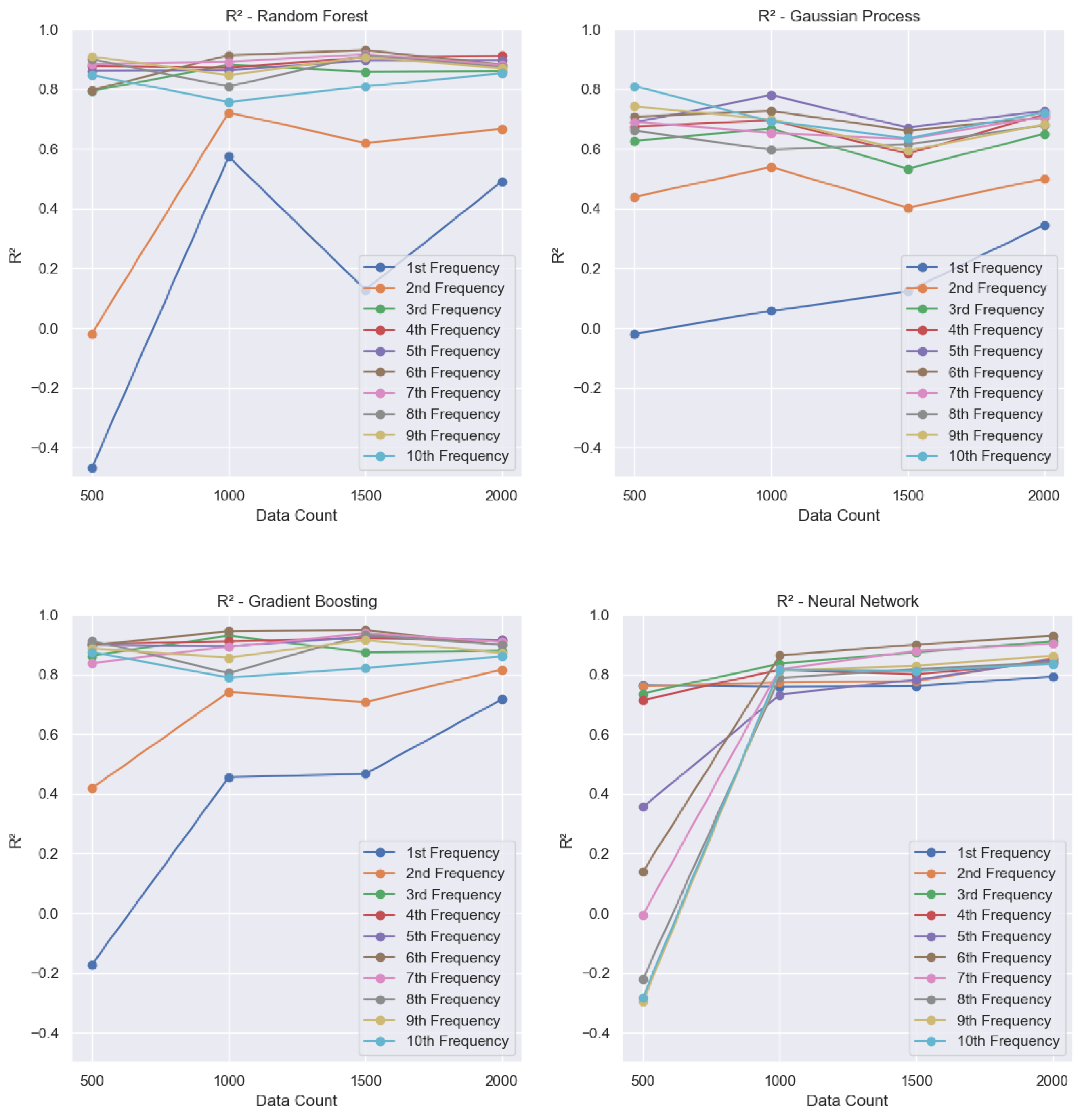

A consolidated view in

Figure 9 highlights the following:

Random Forest: For higher-frequency modes (from the 3rd to the 10th modes), the model achieves values between 0.8 and 0.9. For the smallest dataset, the second frequency has an close to zero, improving as the dataset size grows and reaching around 0.6. For the first mode, the is negative with the smallest dataset and increases with more data, but remains relatively low, stabilizing at around 0.5.

Gaussian Process Regression: For the first frequency, the starts near zero and reaches only about 0.3. For the second frequency, it ranges between 0.4 and 0.5. For higher frequencies, the varies from 0.6 to 0.8. Overall, GPR is the model that consistently delivers the lowest performance across all frequencies.

Gradient Boosting: For the higher frequencies (3rd to 10th modes), values range between 0.8 and 0.9. For the first frequency, the model starts with a negative and improves to approximately 0.7 as the dataset increases. For the second frequency, it starts at around 0.4 and reaches approximately 0.8 with larger training sets.

Neural Network: For the first five frequencies, the values are initially low with the smallest dataset but increase consistently as the training set grows. This model achieved the best overall performance, including the first frequency, which reached values close to 0.8, higher than any other model.

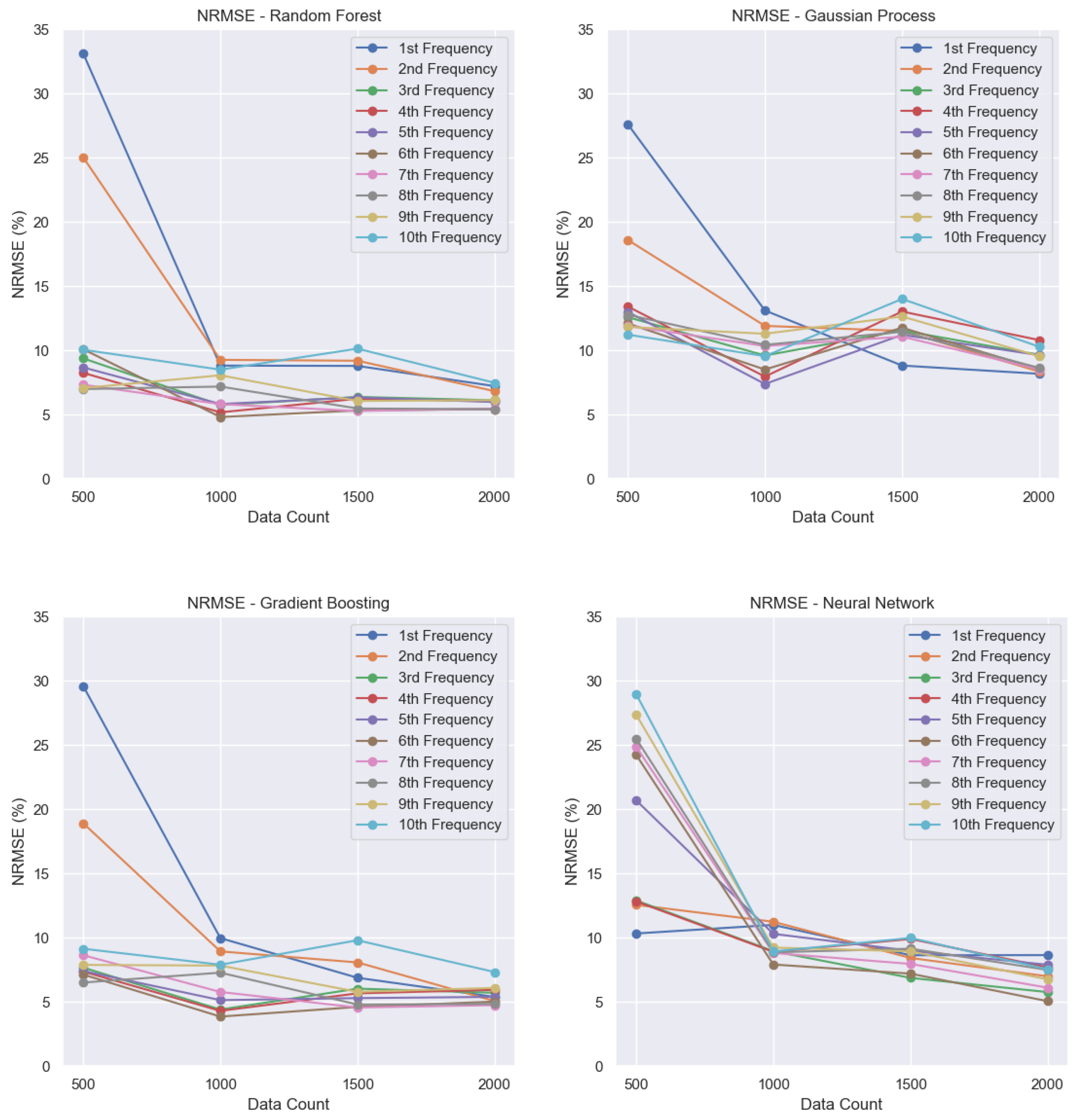

4.2. Normalized Root-Mean-Square Error (NRMSE)

This section analyzes the normalized root-mean-square error (NRMSE) for the models. NRMSE provides a relative measure of prediction error, allowing comparison across frequencies and models as the training set size increases.

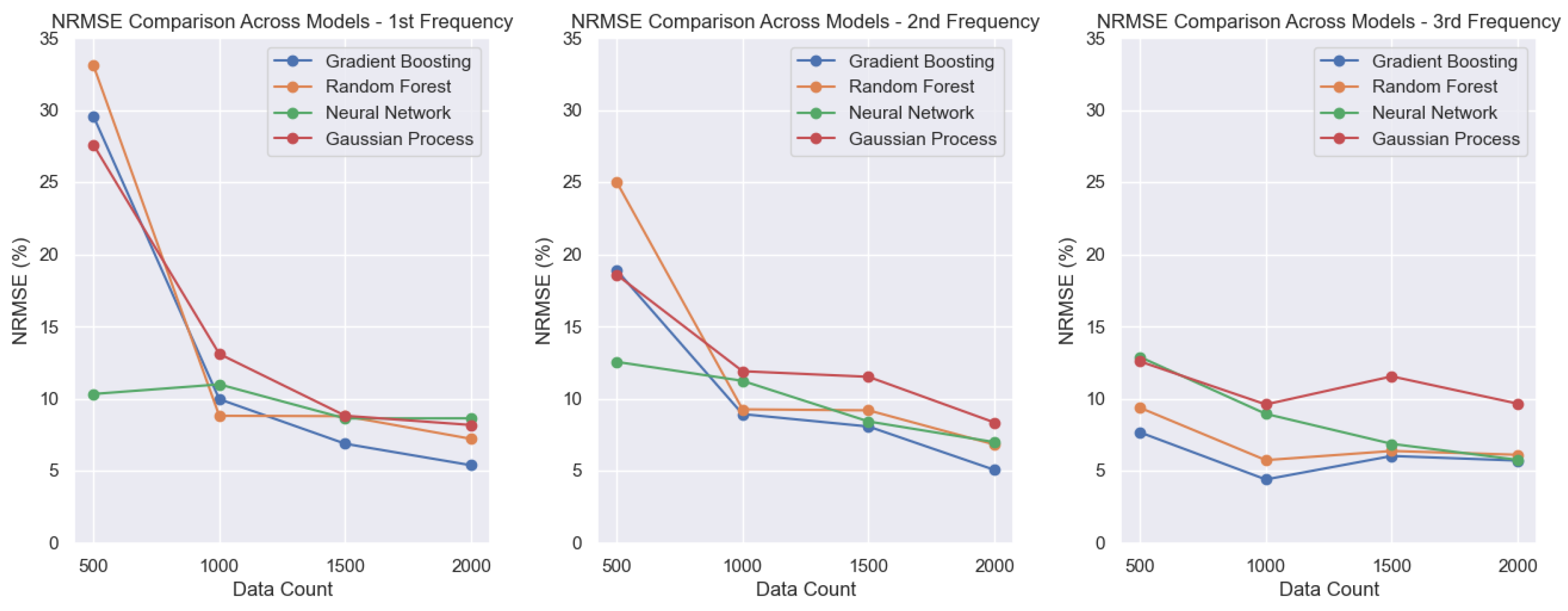

In the lowest modes (

Figure 10), the neural network (NN) achieves the lowest NRMSE with the smallest dataset and continues to improve as the dataset increases. RF, GPR, and GB present high NRMSE values for the smallest dataset, around 30% for the first frequency and 20% for the second frequency, but their performance improves with larger datasets. For the first and second frequencies, GB stands out with the lowest error, around 5%. For the third frequency, GB, RF, and NN achieve similar NRMSE values close to 5%, while GPR once again shows the poorest performance among the models.

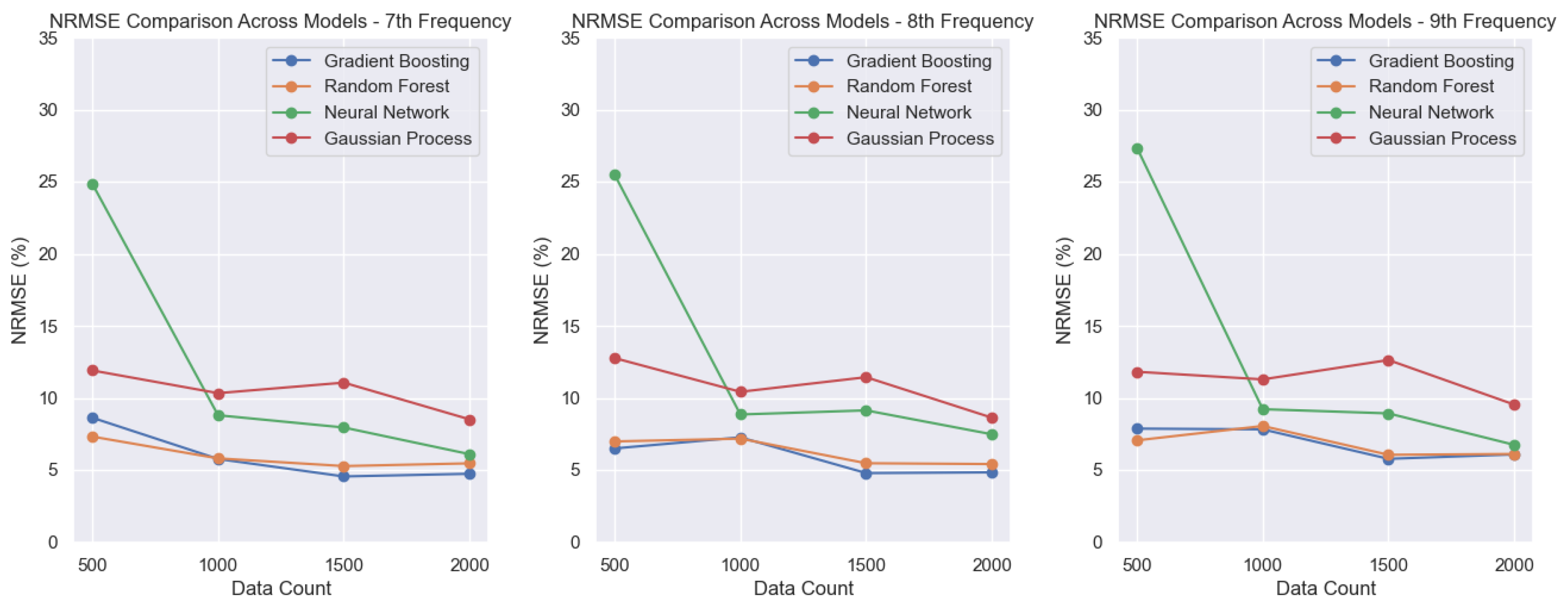

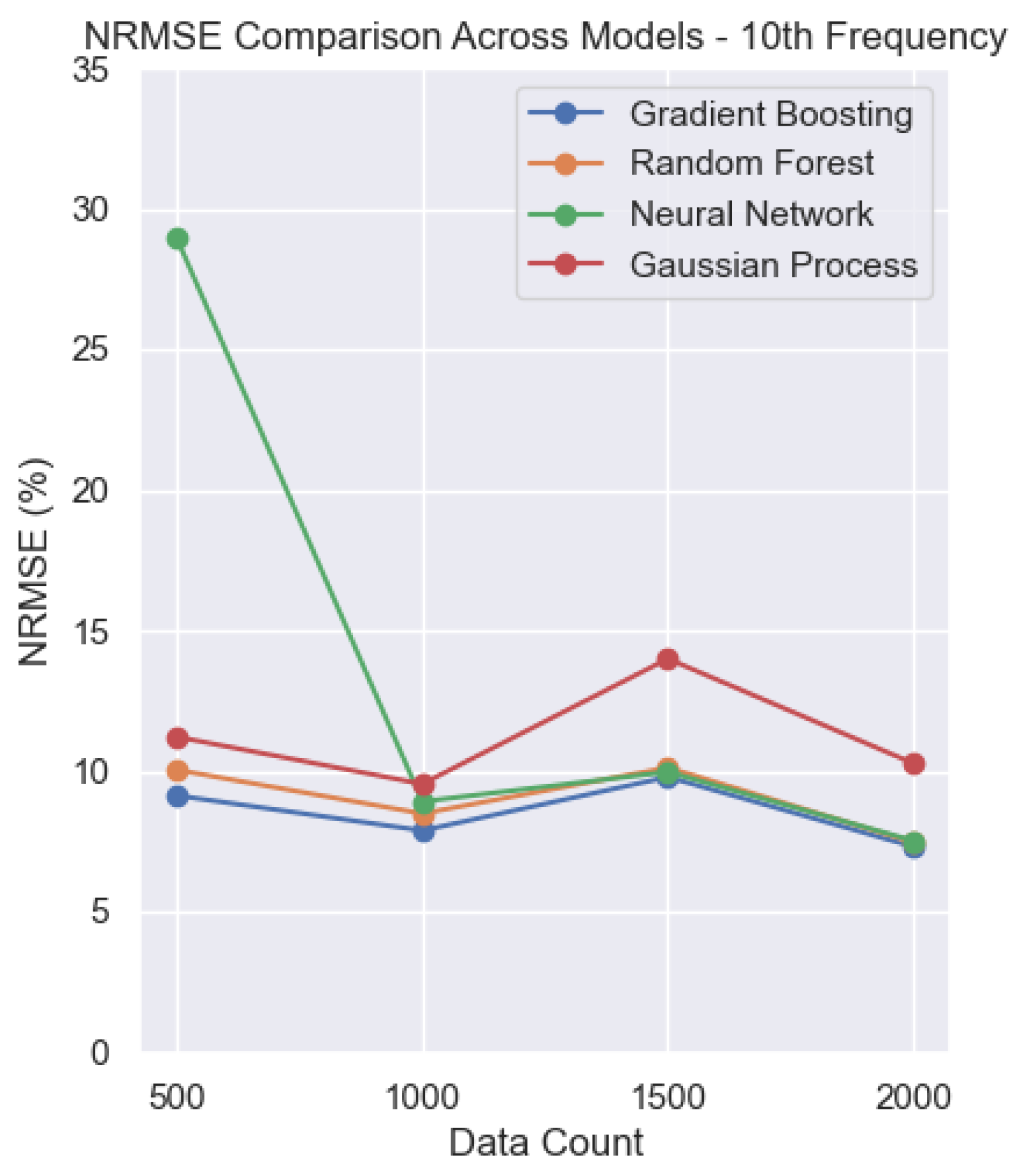

For higher frequencies (

Figure 11,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13), the neural network (NN) shows higher NRMSE values for the smallest dataset, with errors increasing as the frequency rises. However, the NN’s performance improves steadily as the training set grows. Once again, the GPR performs worse than the other models, with NRMSE values of around 10%. The remaining three models achieve lower error ranges, reaching values close to 5%.

Random Forest: The first and second frequencies show high errors with the smallest dataset but improve as the dataset size increases, ultimately reaching NRMSE values of around 5 to 8%.

Gaussian Process Regression: Similarly, the first and second frequencies exhibit high errors with the smallest dataset, with final NRMSE values of around 10%. Overall, this model shows the poorest performance.

Gradient Boosting: The first and second frequencies have high errors for the smallest dataset, but improve significantly, ending with NRMSE values between 5 and 7%. It is the model with the lowest NRMSE overall.

Neural Network: Higher frequencies correspond to larger NRMSE values when trained with the smallest dataset; however, the model reaches NRMSE values of around 5 to 8% for most frequencies as the dataset grows.

Overall, the results demonstrate that Gradient Boosting achieves consistently strong performance, combining low NRMSE values and high scores across most frequencies and dataset sizes. Neural networks excel particularly in low-frequency modes, attaining high and low errors even with limited data, but require larger datasets to reach comparable accuracy at higher frequencies. Random forest shows steady improvements with increased data, providing competitive values and moderate NRMSE, though generally slightly behind gradient boosting and neural networks. Gaussian process regression consistently underperforms, with lower and higher NRMSE values, especially for small datasets and higher frequencies, indicating limitations in model flexibility or data efficiency for this problem.

The superior performance of boosting-based models observed in this study is consistent with previous findings in the machine learning literature for tabular and structured datasets. Gradient boosting methods are well known for their ability to capture complex nonlinear interactions through the sequential correction of residual errors, often leading to strong generalization performance [

32]. Modern implementations such as XGBoost and LightGBM have repeatedly demonstrated state-of-the-art accuracy in regression tasks involving heterogeneous input features and moderate dataset sizes [

33,

34]. In contrast, Gaussian process regression, while theoretically attractive due to its probabilistic formulation and uncertainty quantification capabilities [

35], can suffer from scalability limitations and reduced performance in higher-dimensional input spaces. Therefore, the observed dominance of the boosting approach in the present problem aligns well with previously published results and supports its suitability for surrogate modeling of complex engineering simulations.

The superior performance of the gradient boosting (GB) and neural network (NN) models can be explained by the physical characteristics governing propeller blade dynamics and by the modeling capabilities of these algorithms. Lower-order natural frequencies are primarily controlled by the global mass and stiffness distribution of the blade and vary smoothly with geometric and operating parameters. Neural networks are well-suited to approximate such smooth, high-dimensional relationships, which explains their strong predictive accuracy for the lowest modes. Higher-order frequencies are more sensitive to local geometric variations and rotational effects, leading to nonlinear and nonstationary input–output relationships. Gradient boosting models are particularly effective in capturing these localized behaviors, as they construct piecewise approximations that adapt to complex feature interactions. In contrast, Gaussian process regression tends to smooth these relationships and is more affected by the high dimensionality of the input space, which results in reduced predictive performance for this problem.

5. Conclusions

A data-driven framework was established to forecast the natural vibration frequencies of the propeller blades with high accuracy, providing a valuable tool for modern propeller design and optimization. By coupling a database of 1364 airfoil geometries with high-fidelity ANSYS simulations, the methodology captures the intricate effects of both geometric and operational variables on blade modal behavior.

A feedforward neural network implemented in TensorFlow/Keras was tuned via randomized search cross-validation over layer depth, neuron counts, learning rate, batch size, and optimizer type, yielding strong predictive performance. For higher-order modes, the model attained values above 0.90 and NRMSE below 8%, demonstrating the capability to explain the vast majority of the variance in the simulated data. Although predictions for the lowest frequency mode exhibited relatively greater error, overall accuracy highlights the effectiveness of machine learning as a surrogate for computationally intensive finite element analyses.

Compared to conventional simulation-only workflows, the proposed approach reduces runtime by orders of magnitude and readily scales to new design spaces, making it well-suited for iterative optimization loops in both aerospace and UAV applications. Additionally, the framework’s modularity enables integration with existing CAD and CAE pipelines and facilitates rapid evaluation of novel blade concepts.

Despite enabling large-scale data generation and efficient surrogate model training, the dataset and simulation framework present some limitations. From the initially generated configurations, only 1985 cases successfully converged, which may introduce a selection bias toward geometries that are numerically more stable and easier to mesh. The simulations rely on linear elastic, isotropic material assumptions and idealized boundary conditions at the hub; in particular, the blade root is modeled as a clamped boundary condition at the first airfoil section, representing an idealized hub–blade connection. The simulations do not account for fluid–structure interaction effects, which can influence modal characteristics under real operating conditions. In addition, the use of an automated tetrahedral meshing strategy with a fixed target resolution represents a compromise between accuracy and computational cost, and may limit the fidelity of higher-order modal predictions. Finally, the absence of experimental validation restricts direct assessment of the physical accuracy of both the numerical results and the trained machine learning models, highlighting the need for future studies incorporating experimental measurements.

Future research should focus on expanding the dataset, exploring alternative neural network architectures, and refining simulation parameters to enhance model accuracy, especially for lower-frequency modes. Such efforts will further consolidate the role of machine learning in advancing propeller design, thereby supporting the development of more efficient and sustainable aerospace and UAV propulsion systems.