1. Introduction

Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors (PMSMs) are among the most widely utilized motor types in modern industry, second only to induction motors. Their adoption has increased rapidly due to their capability to deliver high efficiency, excellent torque-to-current characteristics, and compact power density. These advantages make PMSMs especially suitable for applications that require precise and dynamic performance, such as electric vehicles, robotics, aerospace systems, and various medical devices. As a result, PMSMs have become a central component in many high-performance electric drive systems.

PMSMs are typically employed as variable-speed drives in both speed and position control applications. The successful operation of these systems has been enabled by significant advancements in power electronics, signal processing, and embedded control technologies over the past few decades [

1,

2]. In industrial practice, approximately 95% of closed-loop control structures are based on Proportional–Integral–Derivative (PID) controllers. PID control remains popular because of its conceptual simplicity, ease of implementation, and ability to offer acceptable performance under a wide range of operating conditions. Classical tuning methods such as the Ziegler–Nichols rule and various second-order approaches provide straightforward mathematical procedures for determining the proportional (

), integral (

), and derivative (

) gains. However, these conventional PID controllers typically assume linear behavior and stationary dynamics. When the system is affected by disturbances, parameter variations, or inherent nonlinearities, the initially tuned PID gains must be readjusted to maintain stability and performance [

3].

Unlike DC motors, PMSMs exhibit inherently nonlinear and coupled electromagnetic dynamics, which require more sophisticated control strategies [

4]. Although both permanent magnet synchronous motors (PMSMs) and induction motors exhibit nonlinear behavior, PMSMs are particularly affected by nonlinearities due to magnetic saturation, cross-coupling between the d- and q-axis inductances, and the presence of permanent magnet flux. In addition, parameter variations such as temperature-dependent stator resistance and load-dependent inductance changes directly influence the PMSM dynamics, making accurate control more challenging, especially under varying operating conditions. Vector control approaches, also known as field-oriented control (FOC), are widely applied to address this nonlinear behavior. In these systems, PID-based regulators are frequently preferred due to their well-established structure and practical convenience [

5,

6]. Nevertheless, PMSM drives are sensitive to several real-world effects, including flux weakening at high speeds, parameter drift due to thermal variations, magnetic saturation, and performance degradation under load disturbances. These issues significantly challenge the effectiveness of classical PID tuning methods, including the widely adopted Ziegler–Nichols approach, which often proves insufficient in such nonlinear and time-varying environments [

7].

To mitigate these limitations, numerous advanced strategies for PID parameter tuning have been developed. The literature reports solutions such as Genetic Algorithms, online Automatic Tuning, Fuzzy Gain Scheduling, Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), and Adaptive Interaction-based methods [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. For instance, by Nour et al. [

3], a fuzzy logic controller (FLC) was utilized to automatically tune PID gains for PMSM speed control, thereby eliminating the difficulties associated with manual tuning. An Enhanced Robust Fractional-Order PI (ERFOPI) approach capable of maintaining desirable performance even under changing parameters and external disturbances was presented by Zhang and Pi [

7]. Similarly, the Chaos Particle Swarm Optimization (CPSO) algorithm was applied by Rui et al. [

13] to enhance PID tuning precision within vector-controlled PMSM systems. By Fu et al. [

14], a neutrosophic PID tuning scheme was examined, where customized membership functions, cosine-measure theory, and genetic algorithms were employed to achieve optimal tuning. Xiao et al. [

15] proposed a generalized minimum-variance-based auto-tuning PID controller for PMSM speed regulation. Furthermore, a novel adaptive chaotic kinetic molecular theory optimization algorithm (CKMTOA) was utilized by Yi et al. [

16] to determine optimal PID parameters. In another study, a self-tuning PI controller was developed to improve servo drive stability under large inertia and disturbance conditions by Ma et al. [

17]. Adaptive fuzzy tuning structures have also been widely used, as demonstrated in induction motor control by Laoufi et al. [

18] and DC motor speed regulation by Mansor et al. [

19].

Collectively, these studies confirm that enhanced tuning strategies significantly improve the reliability, stability, and dynamic performance of PMSM drives. However, traditional PID controllers, designed largely for linear systems, still face critical limitations when applied to nonlinear systems like PMSMs. Trial-and-error tuning, insufficient disturbance rejection, and lack of adaptability remain persistent challenges. To address these issues, nonlinear auto-tuning PID methods have emerged as promising alternatives, offering improved robustness and adaptability to varying operating conditions [

20,

21].

In this study, a novel auto-tuning PID control strategy is applied to PMSM speed control. The proposed method dynamically adapts the controller gains to achieve rapid convergence and enhanced robustness, even under nonlinear operating conditions. The performance of the proposed approach is validated through both simulation and experimental evaluations and is compared against conventional PI control schemes. The results demonstrate significant improvements in dynamic stability, disturbance rejection capability, and steady-state performance, confirming the method’s potential for high-performance electric drive applications.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents the mathematical model of the PMSM.

Section 3 describes the vector-control system architecture incorporating PID controllers.

Section 4 details the proposed auto-tuning PID strategy.

Section 5 provides the simulation studies, and

Section 6 presents the experimental validation.

2. PMSM Mathematical Equations

The mathematical model of a PMSM is most commonly represented in the synchronous d-q reference frame due to its simplicity and effectiveness in analyzing motor dynamics. This reference frame transforms the three-phase stator quantities into two orthogonal components, enabling decoupled flux and torque control.

In this framework, the stator voltage equations are represented in the synchronous rotating reference frame and are given by Equations (1) and (2). Similarly, the electromagnetic torque produced by the PMSM is defined mathematically as shown in Equation (3) [

22,

23,

24].

In these equations, represents the stator winding resistance, while and denote the stator winding inductances along the d- and q-axes, respectively. The current components along these axes are and , with the corresponding voltage components and . indicates the number of pole pairs, and is the flux generated by the rotor’s permanent magnets. Furthermore, refers to the viscous damping coefficient, is the rotor’s moment of inertia, stands for the electromagnetic torque, and denotes the rotor speed.

These equations form the fundamental basis for analyzing and implementing PMSM control strategies under various operating conditions.

3. Vector-Control System Utilizing PID Controllers

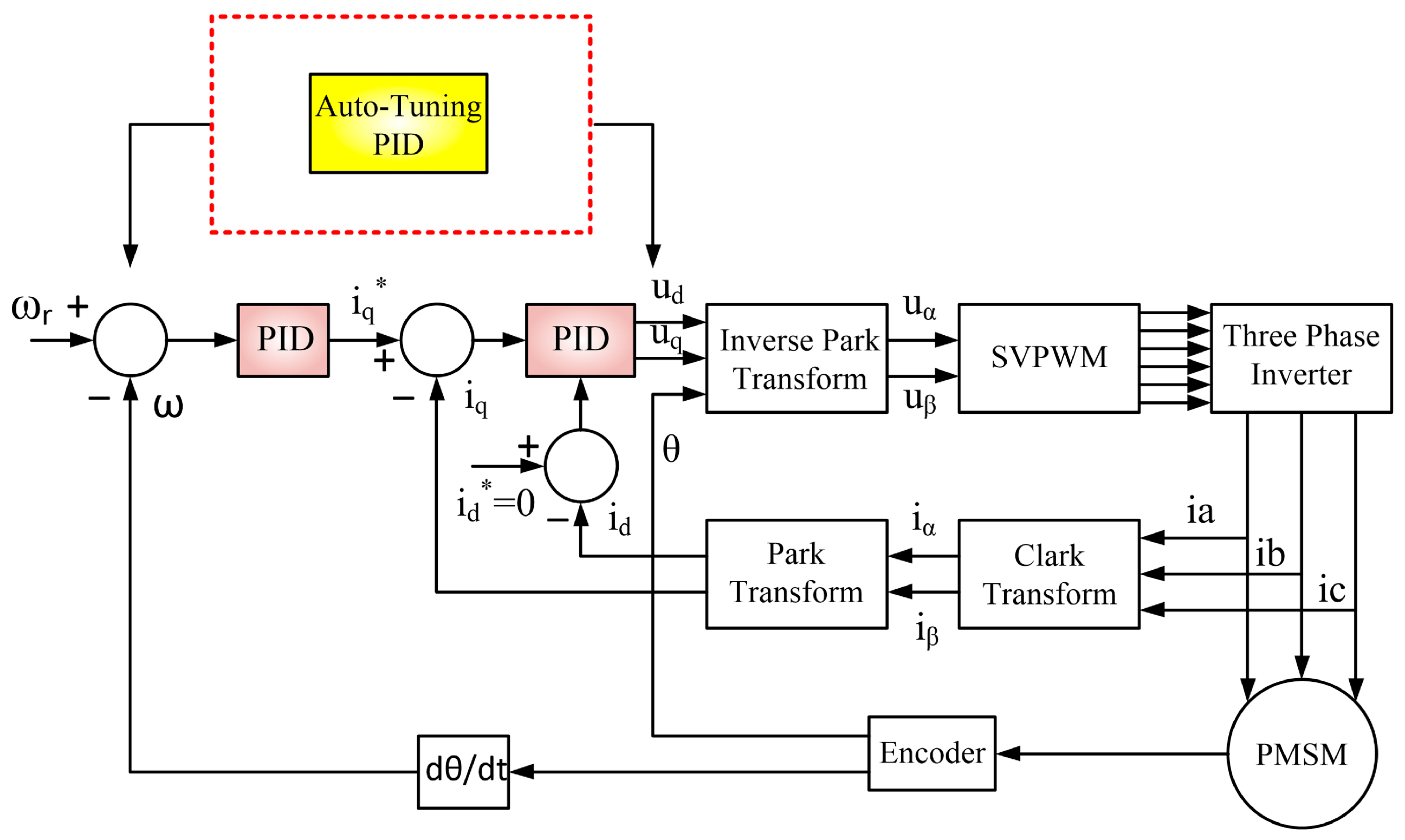

Traditional PID control is a widely used vector control technique, commonly referred to as Field-Oriented Control (FOC). The vector control scheme of a PMSM, illustrated in

Figure 1, integrates two PID controllers: one serving as a speed controller and the other as a current controller. In this scheme, the motor’s speed signal and stator d-axis current are designated as the reference signals. The three-phase stator currents of the motor are measured and subsequently transformed into a two-phase system using Clarke and Park Transformations. This decomposition separates the motor currents into torque (

) and excitation (

) components.

The output of the PID speed controller generates the

reference current, while the PID current controller outputs determine the d- and q-axis stator voltage components. These voltage components are processed through the Inverse Park Transformation to produce Space Vector Pulse Width Modulation (SVPWM) signals, which drive the three-phase inverter circuit [

25,

26].

The PID controller operates by calculating an error signal,

e(

t), which is defined as the difference between the measured signal and the desired reference signal. This error, as described in Equation (4), serves as the basis for the control process, where the primary objective is to minimize the error over time. The PID controller exhibits key dynamic characteristics, including zero steady-state error, fast system response, minimal oscillation, and high stability, making it a reliable control approach for various applications [

27].

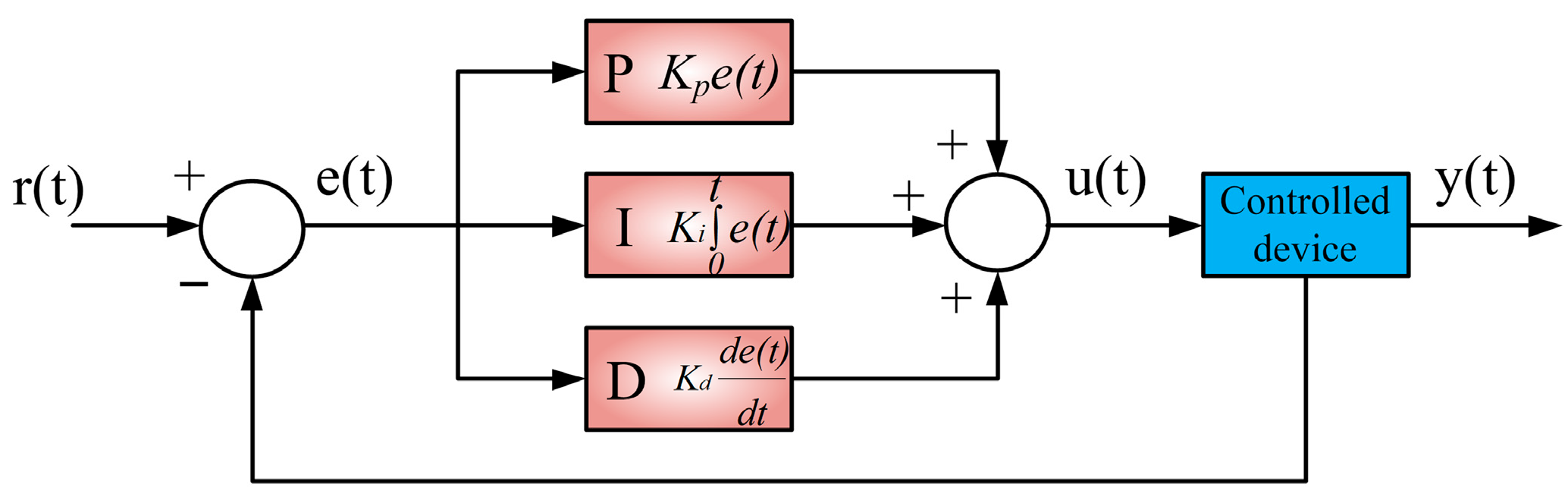

Traditional PID control, a linear control methodology, is extensively employed in the regulation of electric motors. It utilizes three fundamental control parameters: proportional (K

P), integral (K

I), and derivative (K

D) gains, which are independently configured as fixed values during system tuning. These gains determine the respective contributions of the proportional, integral, and derivative components to the control signal, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

The formulas in Equations (5) and (6) represent the mathematical expressions in the time domain and the Laplace s-domain, respectively [

28].

4. Auto-Tuning PID Control

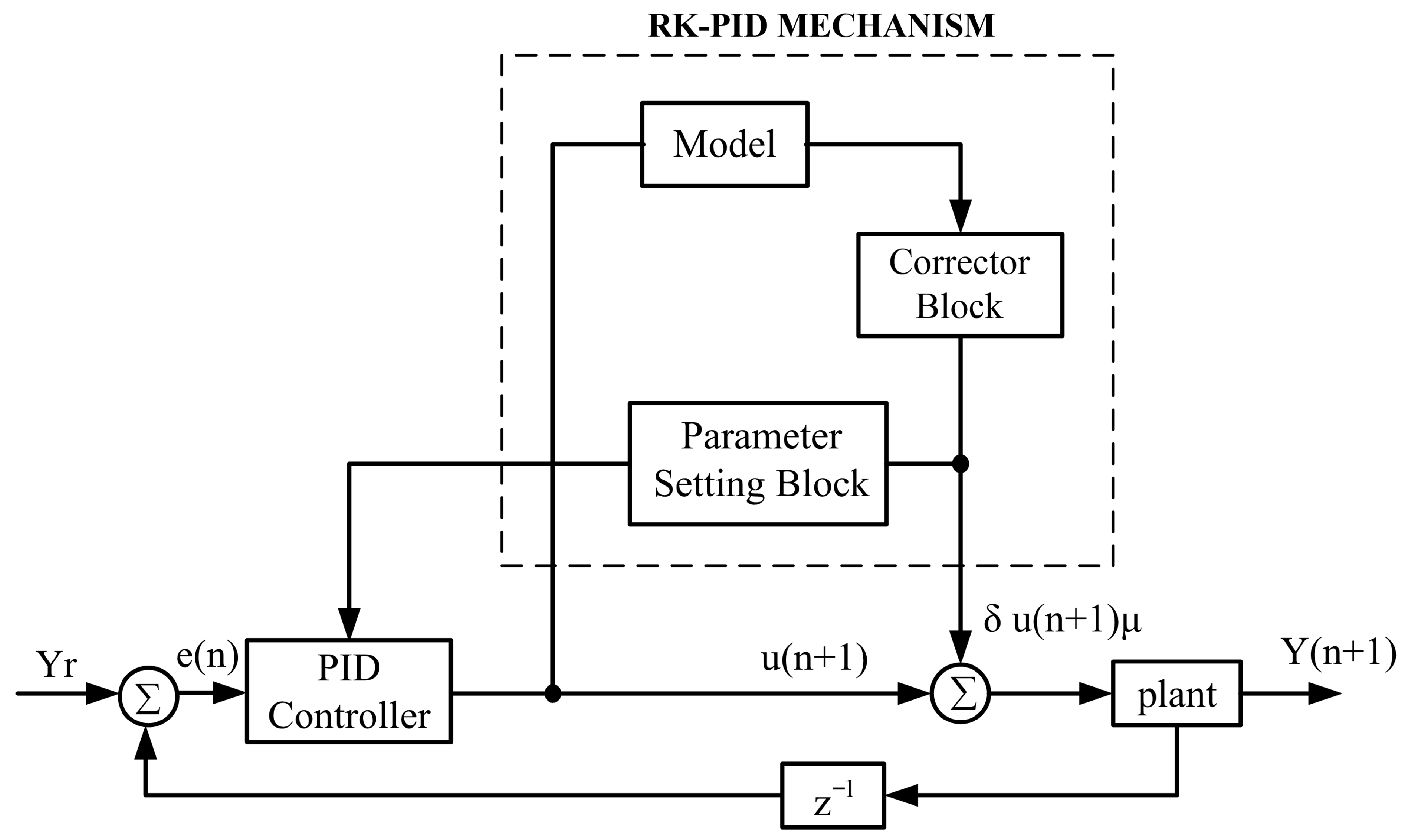

The auto-tuning PID controller, illustrated in

Figure 3, replaces the conventional fixed-gain structure by continuously updating the proportional, integral, and derivative gains during PMSM operation. The proposed framework adopts a model-based adaptive control strategy, comprising a discrete-time system model, two Jacobian matrices, and an adaptive PID computation unit. One Jacobian matrix validates the control input, while the other incrementally adjusts the PID coefficients to enhance control accuracy.

In this configuration,

denotes the reference signal,

represents the predicted output,

is the computed control signal, and

corresponds to the correction term. The instantaneous error

is calculated as the difference between the reference and measured outputs, from which the PID controller generates the control action [

20,

21]. The adaptive mechanism ensures that the PID gains are optimized in real time, maintaining precise control under varying operating conditions.

The overall control structure integrates the discrete model and the two Jacobian matrices,

and

.

validates the control signal, while

updates the PID parameters. The reference signal and candidate voltage input are fed into this block, producing predicted outputs and correction terms. The adaptive PID block updates the control parameters

,

, and

iteratively over a prediction horizon of

steps. The discrete control law is expressed in Equation (7):

The coefficients

,

, and

are adaptively modified through the tuning process. The control signal

is applied iteratively over a prediction horizon of

steps, with optimal parameters obtained by minimizing the cumulative squared prediction error as defined in Equation (8):

In this formulation,

represents the prediction horizon, and

is a regularization factor. To minimize the cost function and update the PID coefficients simultaneously, the Levenberg–Marquardt optimization algorithm is applied as given in Equation (9):

The term μ denotes a damping factor balancing the behavior between the steepest-descent and Gauss–Newton methods, while

is the identity matrix [

20,

21].

The Jacobian matrix and the prediction error vector are defined in Equations (10)–(12), where

.

During each iteration, the PID coefficients are refined using the calculated Jacobian terms, and the objective function is approximated via a second-order Taylor expansion as shown in Equation (13).

The derivative of the cost function with respect to the correction term

δu(n + 1) is then set to zero, yielding the update rule expressed in Equation (14). Subsequently, approximate Jacobian substitutions can be applied as formulated in Equations (15)–(17).

Here, the

,

, and

gains are updated at each iteration within the PID block [

20,

21].

The stepwise procedure of the proposed control algorithm is summarized as follows:

Measure PMSM outputs and compute the instantaneous error .

Calculate the candidate control input from the adaptive PID module.

Predict system outputs for the next steps, .

Compute the Jacobian matrices and along with the correction term .

Update the PID parameters in the controller.

Apply the final control signal to the system.

5. Simulation Studies

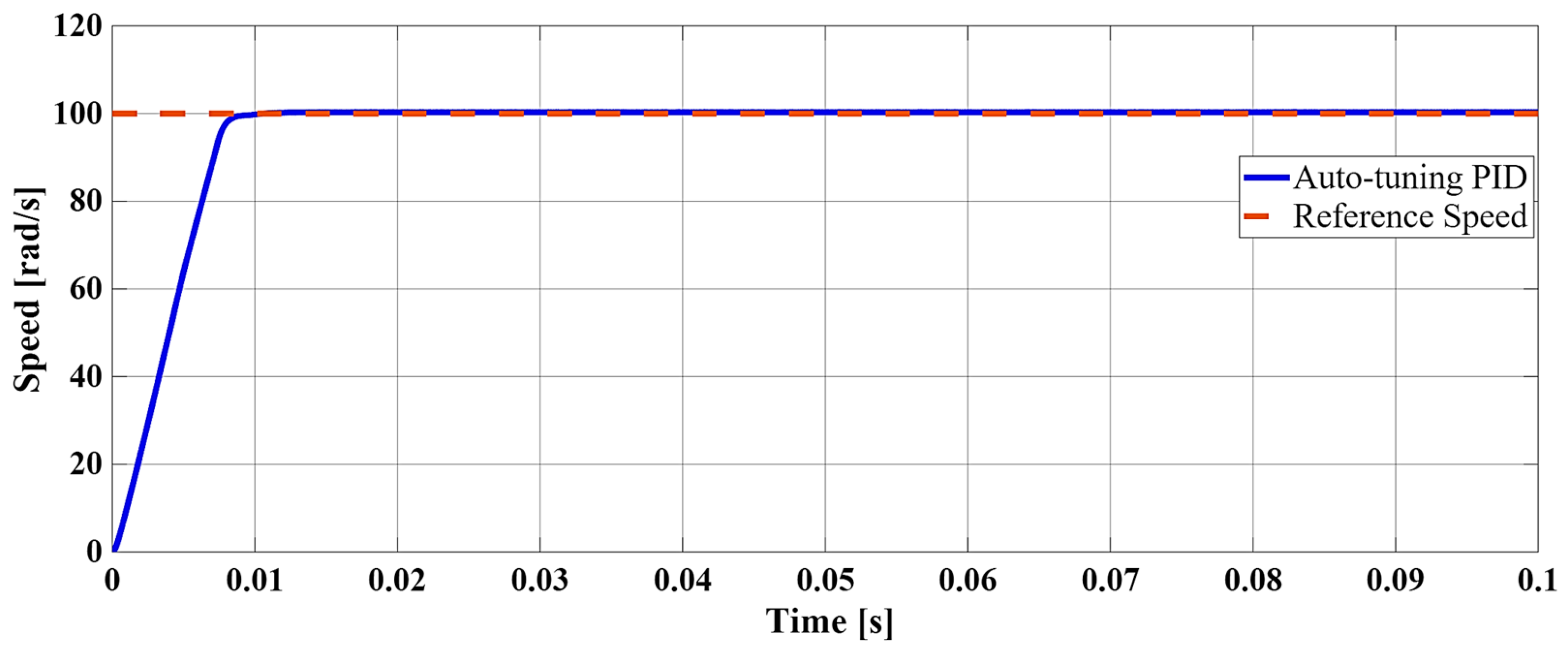

The initial evaluation of the proposed control strategy was performed through simulations in the MATLAB/Simulink R2025b (MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA) environment to verify the effectiveness of the auto-tuning PID controller prior to experimental implementation. The simulation model included the detailed PMSM dynamics and the auto-tuning PID control algorithm, enabling real-time adaptation of the controller gains based on the system’s operating state.

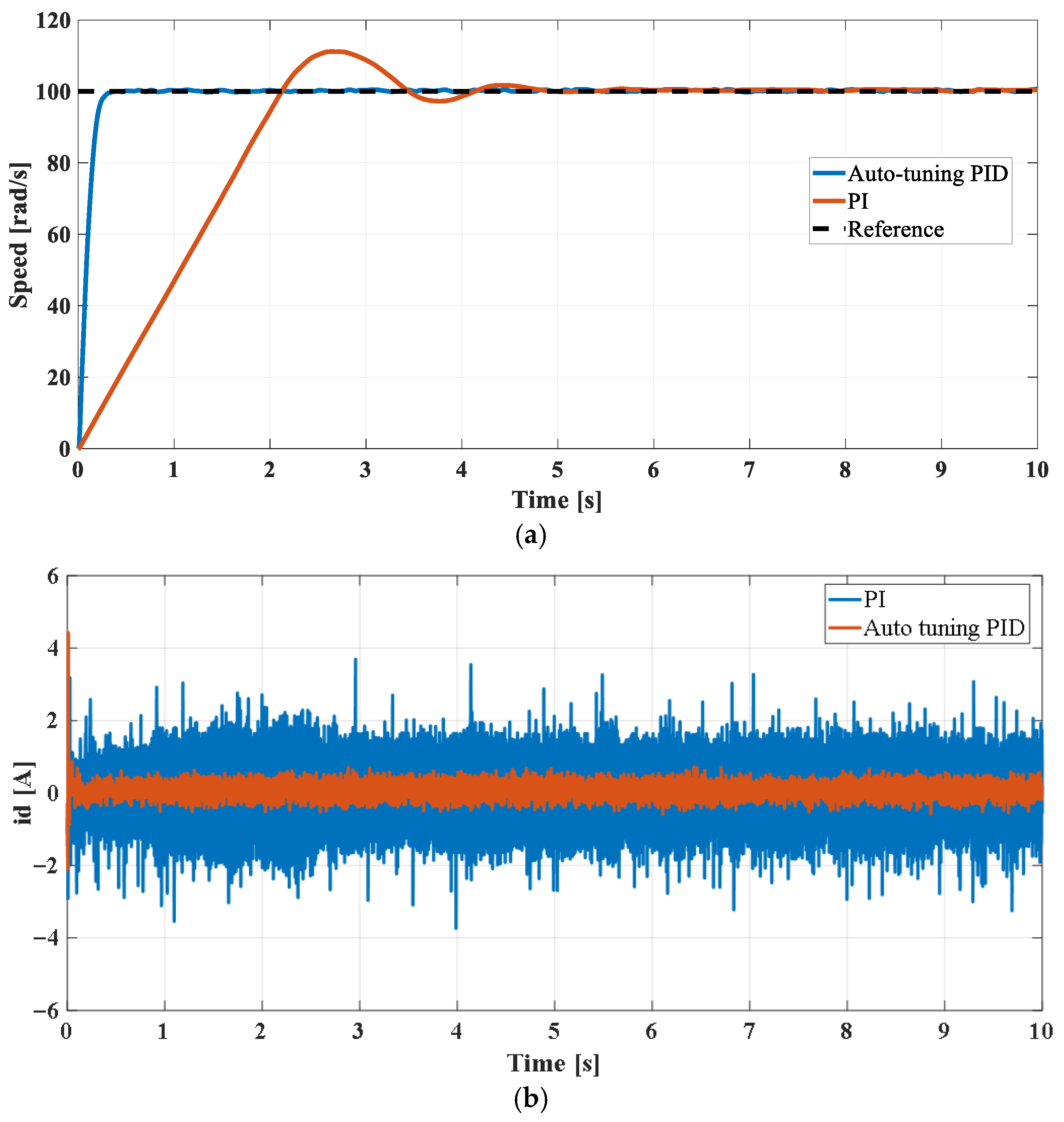

Figure 4 illustrates the performance of the auto-tuning PID controller at a reference speed of 100 rad/s under no-load conditions. As shown, the system rapidly reaches the reference speed without any overshoot, confirming the controller’s capability to provide stable and accurate speed tracking even in the absence of a load. A closer inspection of the initial transient interval reveals that the reference speed is attained within a short rise time, with no noticeable oscillatory behavior. The smooth transient response highlights the effectiveness of the dual-Jacobian-based gain adaptation mechanism in minimizing overshoot and ensuring fast convergence. Compared to conventional fixed-gain tuning approaches, this behavior indicates a more responsive and well-damped dynamic performance, even during the startup phase. Minor oscillations, if any, are quickly damped, demonstrating the robustness of the proposed control strategy for steady-state operation.

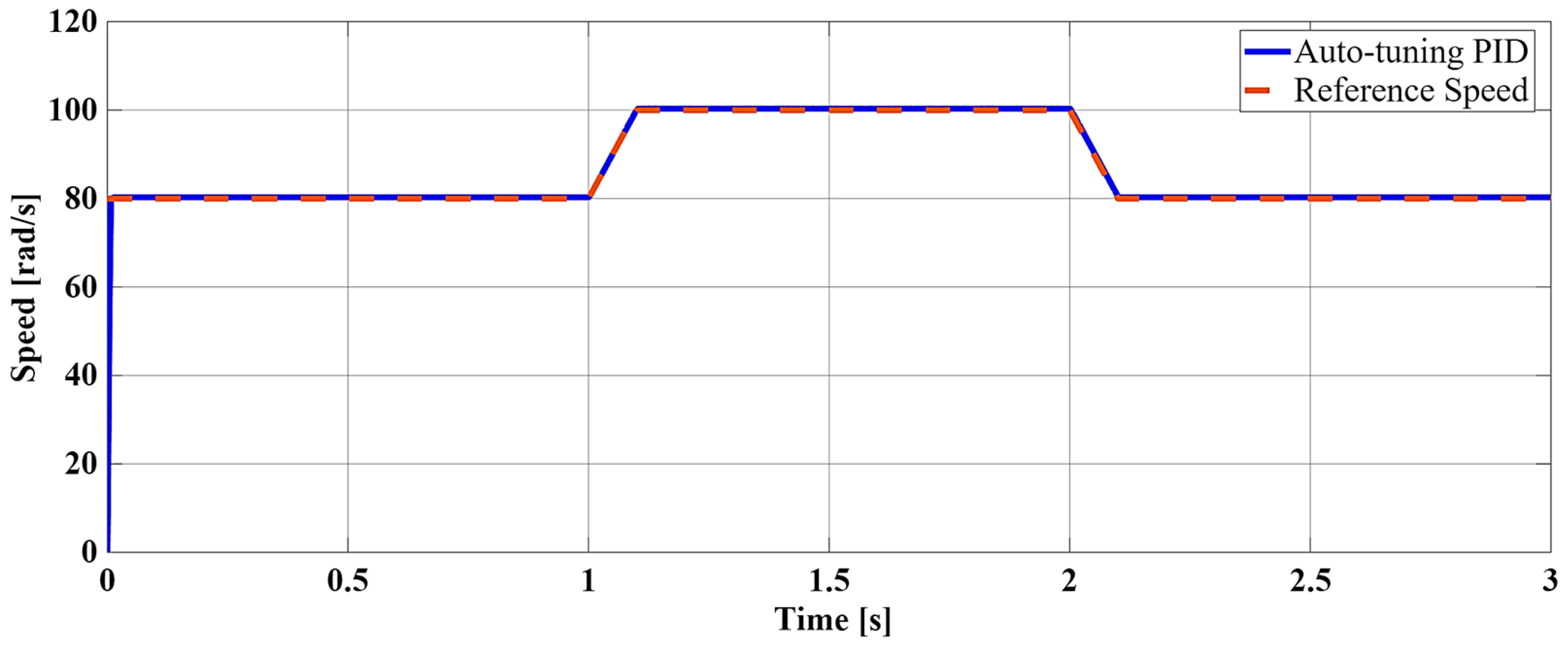

To further evaluate dynamic performance, a step reference velocity input was applied, as depicted in

Figure 5, where both the reference and actual speed responses are presented. The system initially operated at 80 rad/s for the first second, followed by an increase to 100 rad/s, and then returned to 80 rad/s after approximately 2.1 s. As clearly observed in

Figure 5, the auto-tuning PID controller accurately follows the commanded speed transitions with negligible steady-state error and without overshoot, demonstrating a well-damped transient response and stable operation throughout the entire speed range. The short settling time indicates that the online auto-tuning mechanism effectively adapts the PID gains in real time in response to sudden variations in the reference speed. This adaptive gain adjustment compensates for abrupt dynamic changes, ensuring minimal transient error and rapid convergence to the desired operating point. Moreover, the smooth speed trajectory during both acceleration and deceleration phases implies that the proposed controller maintains proper current regulation and avoids excessive control effort, thereby preserving safe operating conditions for the PMSM drive. These results confirm that the proposed auto-tuning PID controller is capable of handling abrupt speed variations while maintaining both speed accuracy and system robustness.

Overall, the simulation studies confirm the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed auto-tuning PID controller under both steady-state and transient operating conditions. Rather than focusing on individual test cases, these results collectively demonstrate that the controller design provides reliable and consistent performance across different operating scenarios. Consequently, the simulation outcomes establish a solid basis for the subsequent experimental investigations, indicating that the proposed control strategy is well-suited to address practical variations in motor dynamics and the requirements of high-performance PMSM drive applications.

6. Experimental Studies

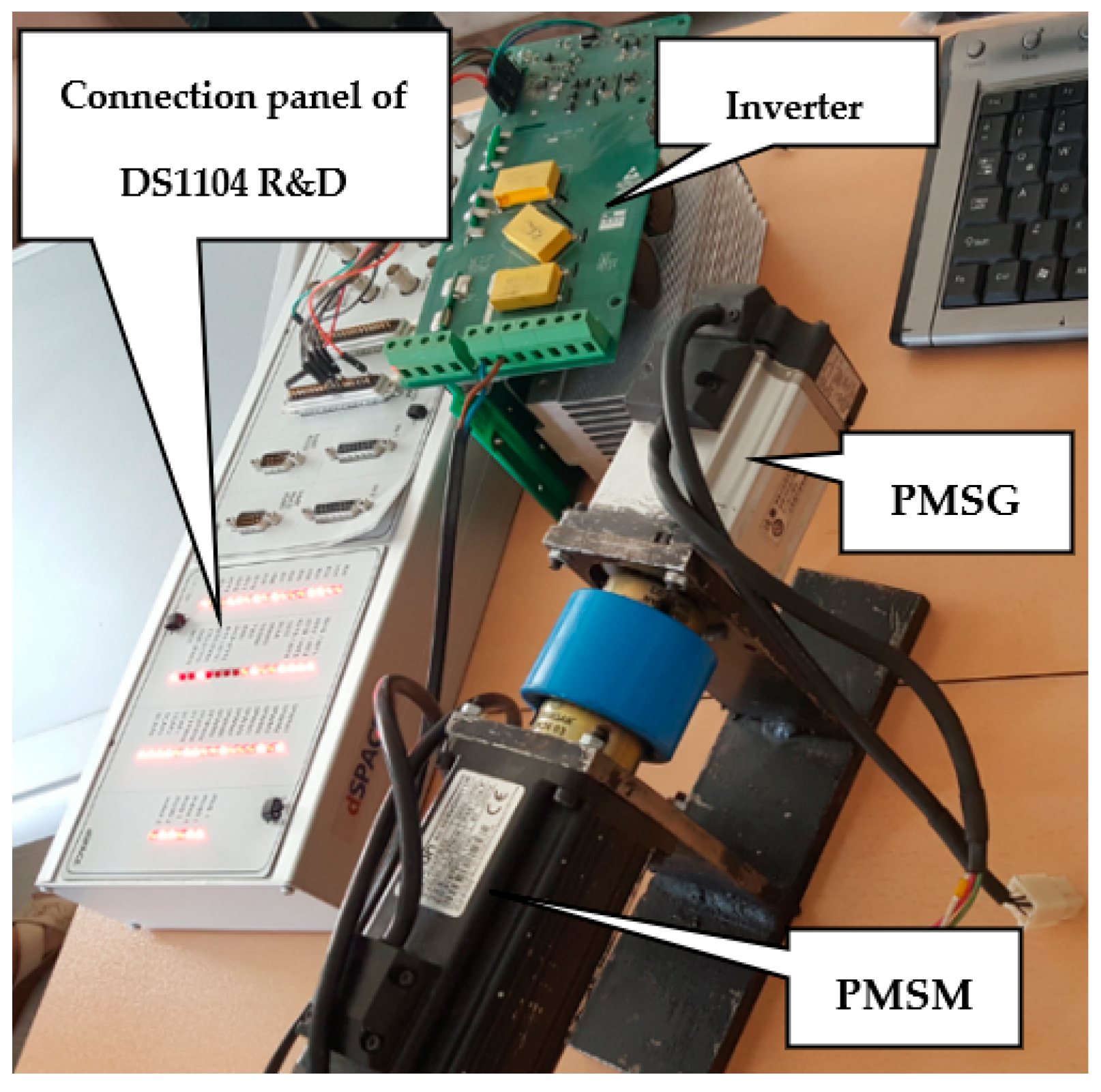

The dSPACE DS1104 controller board (dSPACE GmbH, Paderborn, Germany)was utilized for conducting real-time experimental studies. The experimental setup consists of a PMSM for speed control and a second permanent magnet synchronous generator (PMSG) coupled to the PMSM to serve as a controllable load, enabling investigation of dynamic motor behavior under realistic operating conditions. As illustrated in

Figure 6, the setup integrates the PMSM, PMSG load, inverter, sensors, and the dSPACE DS1104 control platform, allowing real-time execution of both conventional PI and auto-tuning PID control algorithms. The sampling time of 5 kHz was selected to ensure high-fidelity signal acquisition and precise control execution, enabling accurate observation of fast transient dynamics in MIMO nonlinear systems. This high sampling rate is particularly beneficial for capturing subtle current oscillations and transient responses during step changes.

The PMSM specifications employed in this study are as follows: 1.27 Nm rated torque, 3000 r/min rated speed, 4 pole pairs, 2.5 Ω stator resistance, and 7 mH stator inductance. The PMSG load allows the emulation of realistic torque variations, providing a thorough evaluation of both conventional PI and proposed auto-tuning PID controllers under varying operational conditions. In this study, the classical fixed-gain PI controller is selected as the reference benchmark, as it represents the most commonly adopted control structure in industrial PMSM drive systems due to its simplicity, robustness, and ease of implementation within field-oriented control frameworks. The comparison is therefore focused on evaluating the added value of the proposed auto-tuning PID strategy, rather than comparing different controller orders.

Both controllers were initially evaluated at a reference speed of 100 rad/s. For a fair comparison, the gains of the classical PI controller were tuned using a two-stage procedure. Initial tuning was carried out in MATLAB/Simulink through simulation-based analysis to ensure system stability and adequate damping. Subsequently, the gains were fine-tuned experimentally on the dSPACE DS1104 platform using ControlDesk under real-time operation. The final gains were selected to minimize overshoot, settling time, and steady-state error across different operating conditions.

For the sake of reproducibility, the final PI gains used in the experimental studies are as follows: for speed control,

and

; for current control,

and

. This tuning approach reflects common industrial practice for fixed-gain PI controllers in PMSM drive systems. The experimental results are presented in

Figure 7.

Figure 7a shows that the auto-tuning PID controller rapidly tracks the desired reference speed without overshoot, exhibiting a short settling time and negligible steady-state error, highlighting its ability to dynamically adjust gains in real time to compensate for nonlinearities. Conversely, the conventional PI controller reaches the reference speed within approximately 2 s with minimal overshoot, while the settling time is observed to be approximately 5 s.

Figure 7b presents the corresponding id current response, demonstrating that the auto-tuning PID maintains the current tightly at 0 A, while the PI controller exhibits small oscillations, indicating less precise d-axis current regulation. These oscillations in the PI controller may lead to minor energy losses and reduced efficiency during transient events, corresponding to increased integral performance indices during dynamic operation.

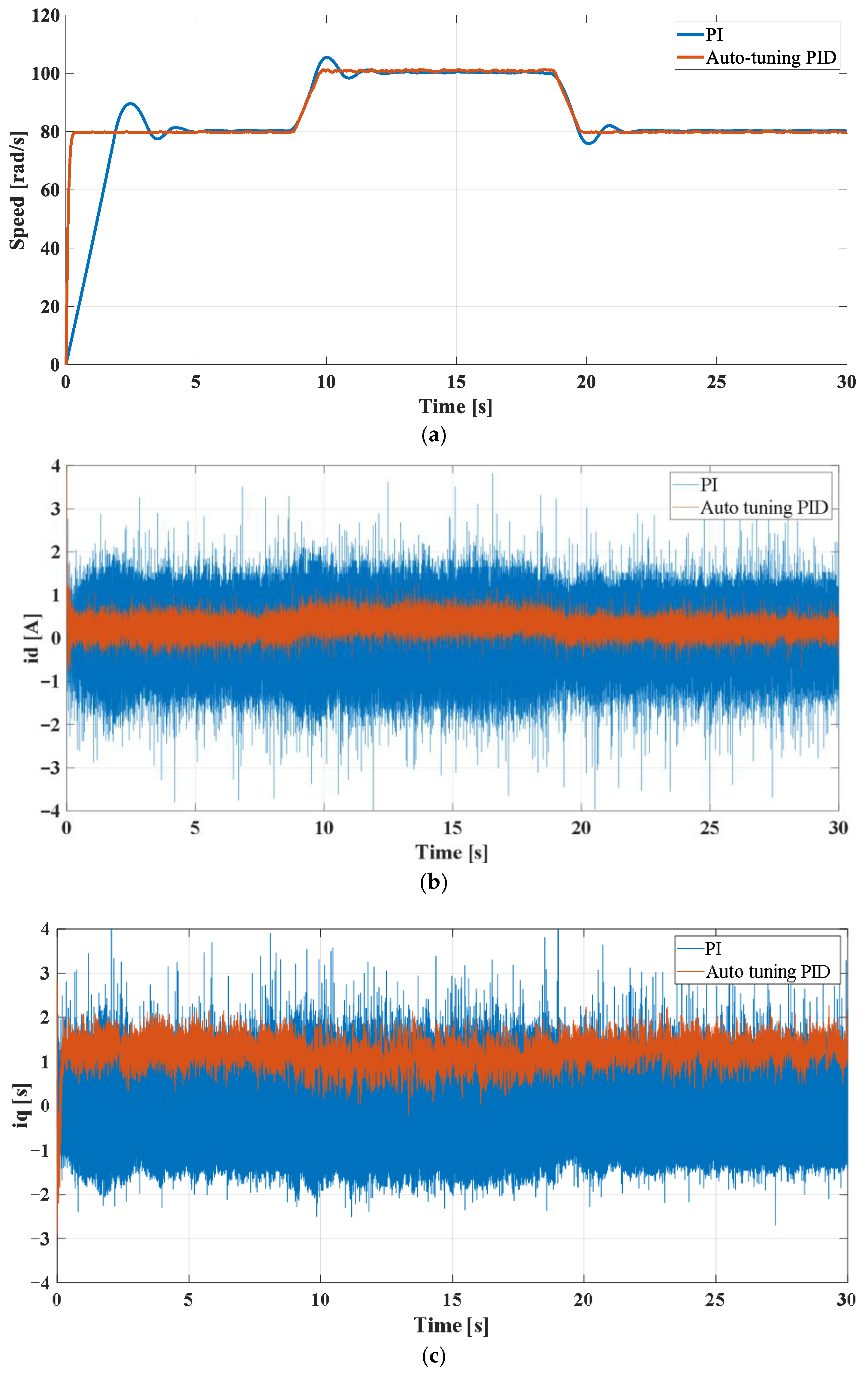

Step reference experiments were conducted to further assess dynamic performance of the control strategies under load conditions. The reference speed was initially set to 80 rad/s, increased to 100 rad/s at approximately the 10th second, and then returned to 80 rad/s after the 20th second. The corresponding speed and current responses of both the classical PI and the proposed auto-tuning PID controllers are presented in

Figure 8a–c.

Figure 8a illustrates the speed responses, while

Figure 8b,c show the corresponding d-axis (id) and q-axis (iq) current responses, respectively. Although the PI controller is able to reach the desired speed levels with relatively small speed deviations, noticeable oscillations are observed in both the id and iq currents, indicating reduced robustness under dynamic operating conditions.

The load torque applied by the coupled PMSG was kept constant during the experiments. The observed decrease in the q-axis current at higher speeds is therefore attributed to the improved efficiency of the control strategy and the reduction in torque-producing current ripple once steady-state operation is reached, rather than to a decrease in load torque.

In contrast, the auto-tuning PID controller accurately tracks the reference speed transitions without overshoot. At the same time, both id and iq currents remain tightly regulated throughout the experiment. The id current stays close to zero, minimizing reactive power consumption, while the iq current closely follows the torque demand, ensuring accurate and efficient torque production. These results clearly demonstrate the superior transient performance and robustness of the proposed auto-tuning PID controller under sudden reference speed changes.

Overall, the experimental study confirms that the auto-tuning PID controller provides enhanced tracking performance, improved current regulation, and increased robustness against disturbances compared to the conventional fixed-gain PI controller. The combination of a high sampling rate, accurate current measurement, and real-time gain adaptation enables a comprehensive evaluation of the controller’s performance under realistic operating conditions. These findings highlight the suitability of the proposed control strategy for high-performance PMSM applications requiring precise, adaptive, and real-time control.

7. Conclusions

In this study, an auto-tuning PID controller was developed and experimentally validated for the speed regulation of a Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor (PMSM), a nonlinear and inherently coupled MIMO system. The proposed approach leverages two Jacobian matrices: one for generating the verification term used in refining the control input, and another for dynamically updating the PID gains according to the instantaneous operating conditions of the motor. This dual-Jacobian structure enables the controller to adapt its parameters in real time, ensuring reliable tracking performance even under varying load and speed transitions.

Experimental implementation was carried out on a dSPACE DS1104 real-time control platform, allowing a direct comparison between conventional fixed-gain PI control and the proposed auto-tuning PID strategy. The results clearly demonstrate that while the baseline PI controller introduces overshoot and exhibits slower convergence under rapid reference variations, the auto-tuning PID maintains smooth and overshoot-free tracking behavior. This improvement is attributed to the controller’s ability to continuously reshape its gains based on system dynamics, thereby compensating for nonlinearities and cross-couplings that typically degrade the performance of traditional controllers.

Beyond its favorable transient response, the auto-tuning PID controller also improves overall robustness against parameter variations and external disturbances. The adaptive mechanism ensures that the controller maintains stability and consistent performance without requiring extensive manual tuning, which is often time-consuming in practical applications. The experimental findings thus validate the effectiveness of the method and highlight its suitability for high-performance motor drive systems where real-time adaptability is essential.

Overall, the proposed auto-tuning PID framework presents a promising alternative for advanced PMSM drives, offering enhanced stability, improved dynamic behavior, and reduced dependence on offline tuning procedures. Future work may focus on extending the methodology to field-oriented control structures, incorporating load torque estimation into the adaptation mechanism, or deploying the approach on embedded microcontroller platforms for cost-effective industrial integration. The strong experimental results obtained in this study indicate that the method has significant potential for broader adoption in nonlinear motor control applications.