Braking Energy Recovery Control Strategy Based on Instantaneous Response and Dynamic Weight Optimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

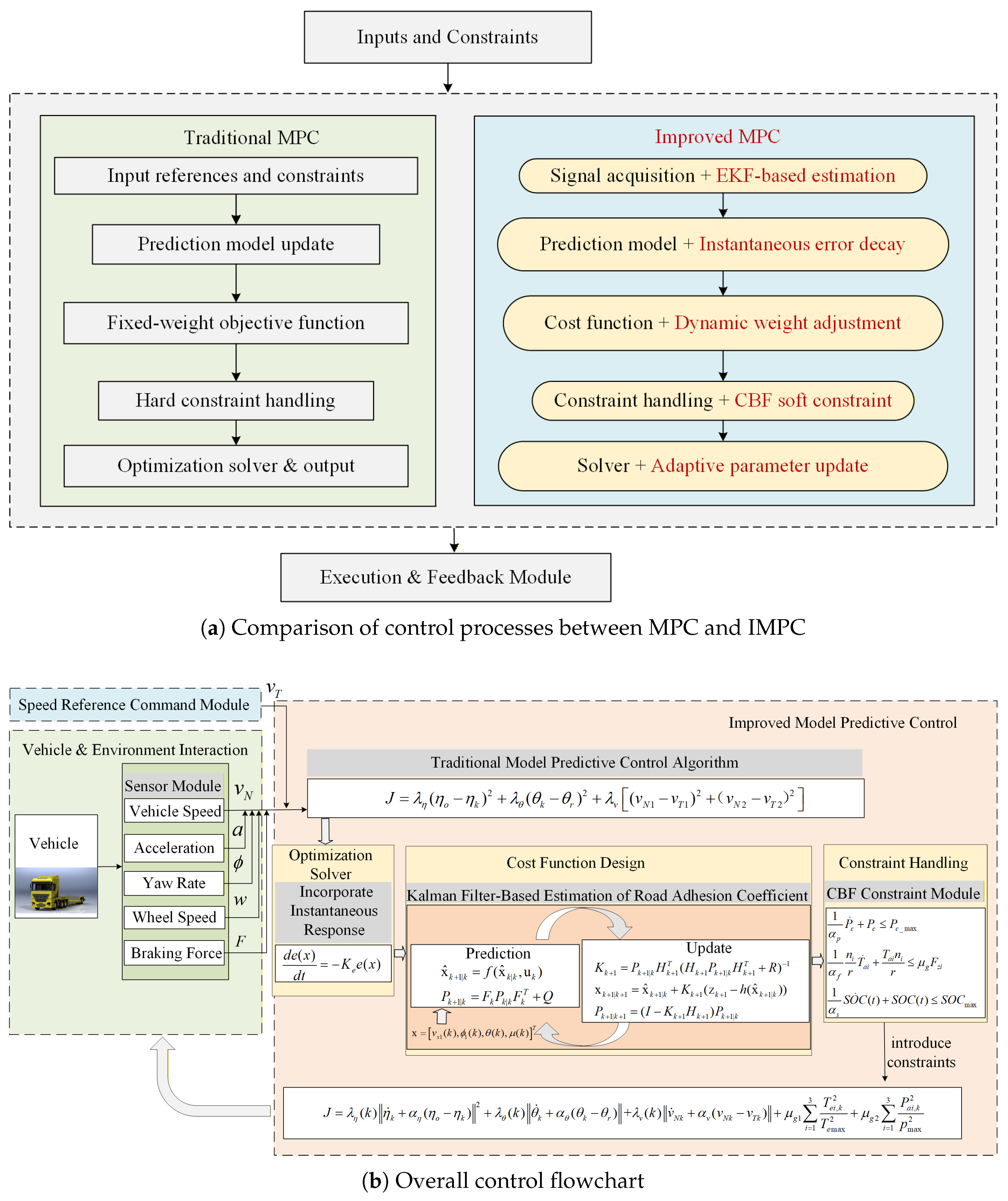

- Section 3.3: A first-order error attenuation mechanism is introduced into the MPC framework to enhance computational efficiency and reduce control delay, enabling the motor braking torque to respond promptly under transient conditions and improving recovery continuity.

- Section 3.4: An extended Kalman filter (EKF) is employed for real-time estimation of the road adhesion coefficient. The estimated value dynamically adjusts the weighting factors between energy recovery and stability, increasing regenerative braking on high-adhesion surfaces while maintaining stability on low-adhesion roads, thereby enhancing average recovery efficiency over the entire braking cycle.

- Section 3.5: A control barrier function is incorporated into the constraint-handling process, allowing gradual satisfaction of constraints to prevent abrupt recovery interruptions and ensure the smoothness and continuity of the braking process.

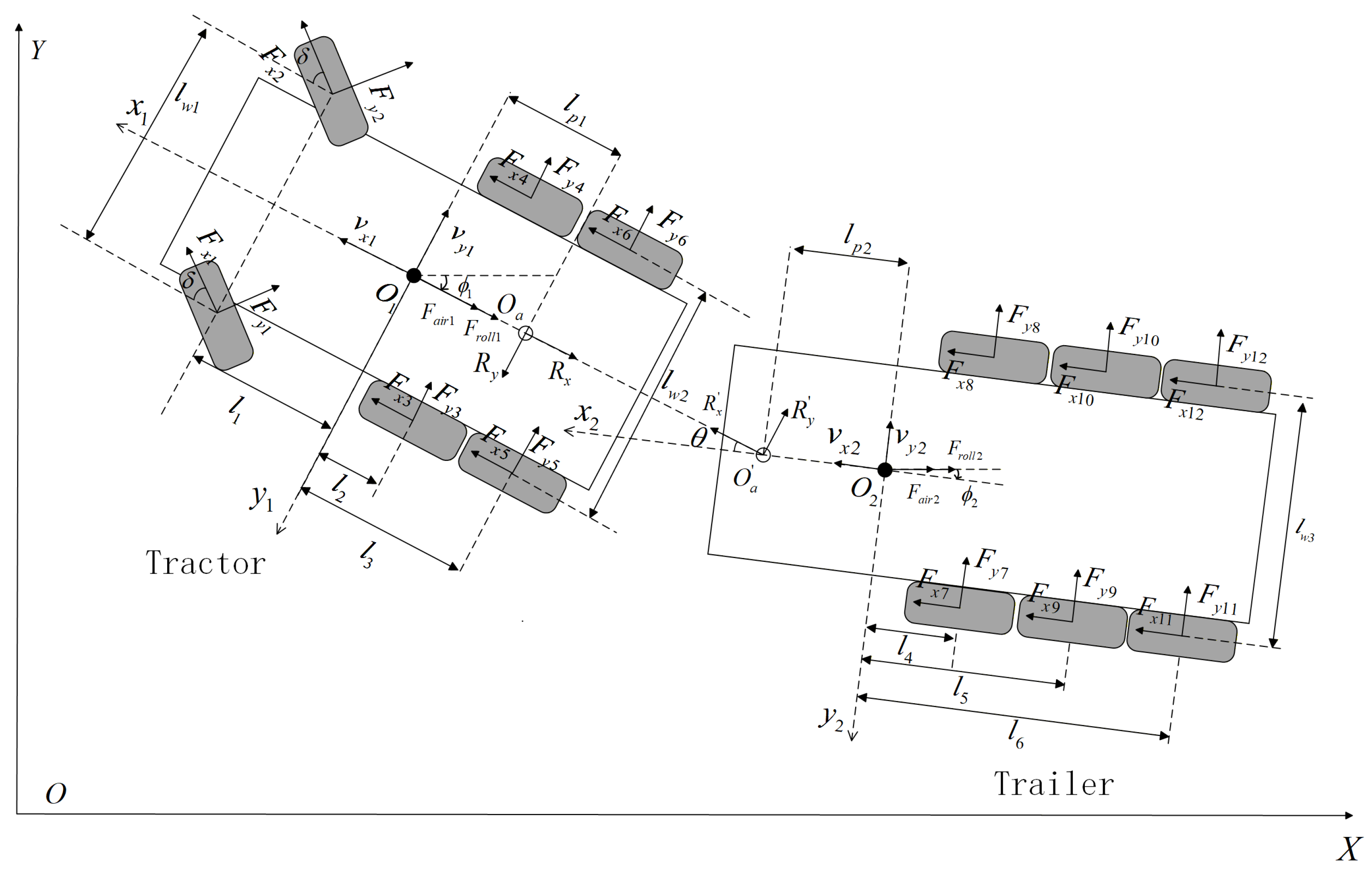

2. Multi-Axle Electric Heavy Truck Vehicle Model

2.1. Vehicle Dynamics Model

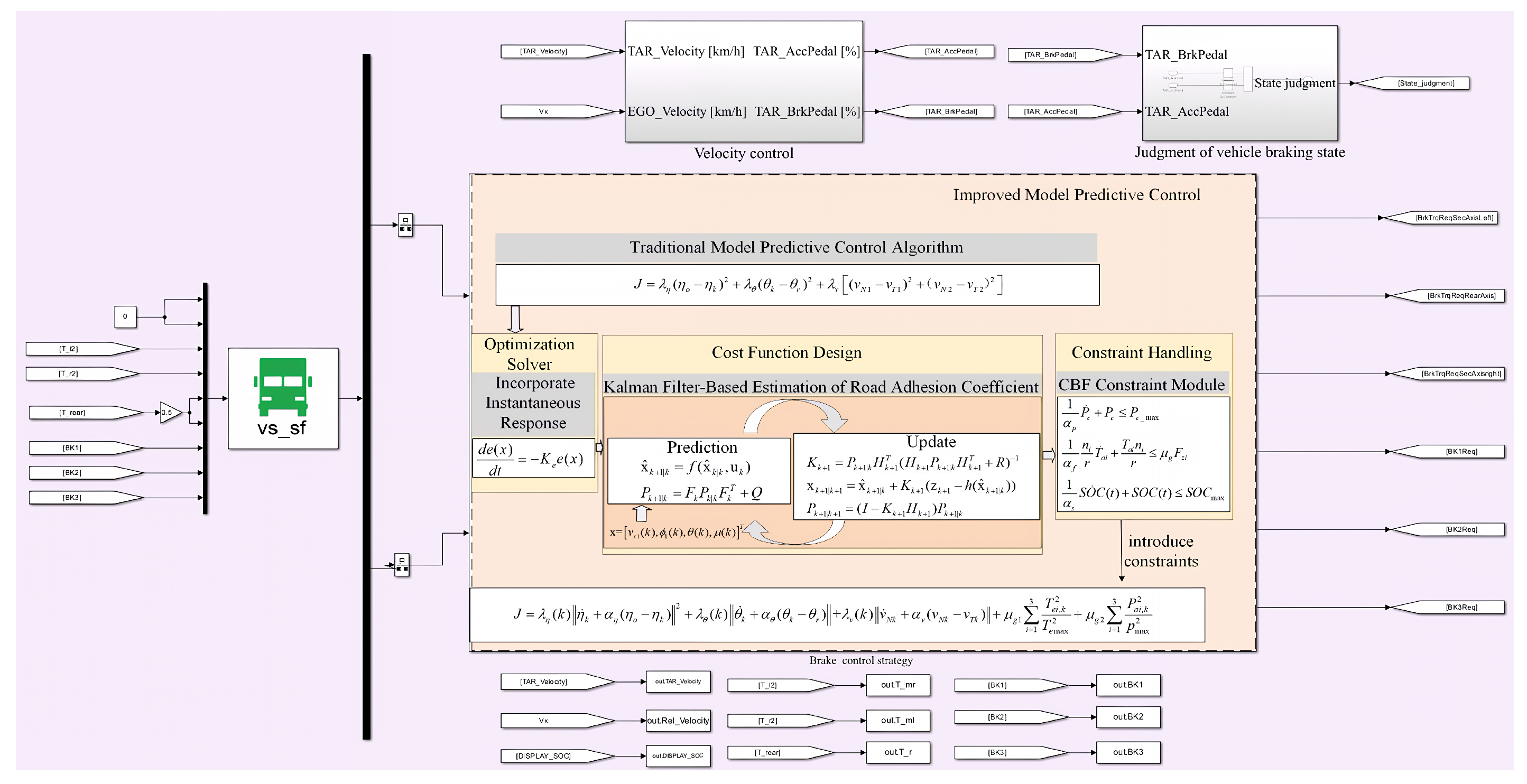

- Based on the driver’s braking demand and the real-time status of each subsystem, the VCU computes the target control signals for both pneumatic and regenerative braking.

- Once the braking command is issued, the pneumatic regulating valves (Pressure Regulating Valve 1, 2, and 3) transmit compressed air through pipelines (yellow circuits) to the brake chambers, thereby generating mechanical braking torque at the wheels.

- Simultaneously, the VCU sends regenerative braking commands to the motor controllers, which in turn regulate the corresponding motors to initiate energy recovery.

- (1)

- Selection of degrees of freedom and state variables. Based on the above definitions of coordinate frames and degrees of freedom, the tractor and semitrailer are modeled as rigid bodies moving in the horizontal plane, each with three degrees of freedom in the longitudinal, lateral and yaw directions, so that the whole system has six degrees of freedom in total. The longitudinal and lateral velocities of the centers of gravity in the body-fixed frames, and , together with the yaw angles and , are chosen as the state variables. Their relations to the velocities in the global frame and are given by Equations (1) and (2).

- (2)

- Rigid-body dynamic equilibrium equations. Taking the body-fixed frames of the tractor and semitrailer as references, Newton’s second law and Euler’s rotational equation are applied in the longitudinal, lateral and yaw directions for each rigid body i (tractor , semitrailer ), leading to the general form.where , and denote the resultant longitudinal force, lateral force and yaw moment acting on body i, respectively.

- (3)

- Modeling of external forces and articulation constraints. According to the simplified linear tire-force relations adopted in this paper, the longitudinal and lateral tire forces of each wheel group are expressed (e.g., , ). The aerodynamic drag forces , the rolling resistance forces , and the interaction forces at the fifth wheel are also included and substituted into the force and moment balance equations in step (2). In addition, the kinematic constraints at the articulation point between the tractor and semitrailer are formulated on the basis of the geometric relations and velocity compatibility conditions, as given in Equation (6), which couple the longitudinal, lateral and yaw motions of the two units.

- (4)

- Assembly and rearrangement of the system equations. On the basis of the dynamic equations and articulation constraints obtained in steps (2) and (3), the internal constraint reactions are eliminated by means of the articulation constraints, and the force and moment balance equations of the tractor and semitrailer are assembled and rearranged. In this way, the coupled dynamic equilibrium equations of the combination vehicle in the longitudinal, lateral and yaw directions are obtained, whose compact state-space form is given by Equations (4)–(6).

2.2. Braking Energy Consumption Model

3. IMPC Algorithm

3.1. Overall Strategy for Energy Recovery Control

3.2. Algorithm Framework

3.3. Instantaneous Response Reformulation

3.4. Road Adhesion Based Weight Adjustment

3.5. Constraint Optimization Based on CBF

3.6. Improved MPC Algorithm Summary

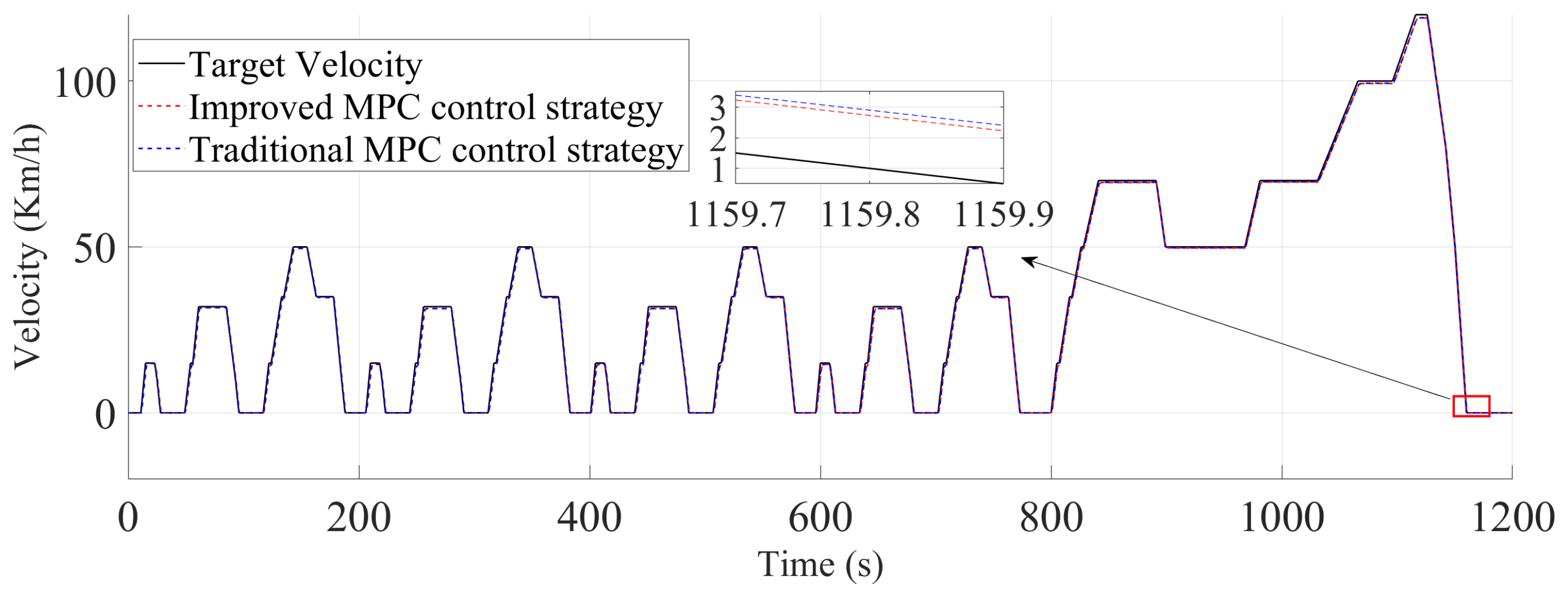

4. Simulation Experiments

4.1. Friction Coefficient Estimation

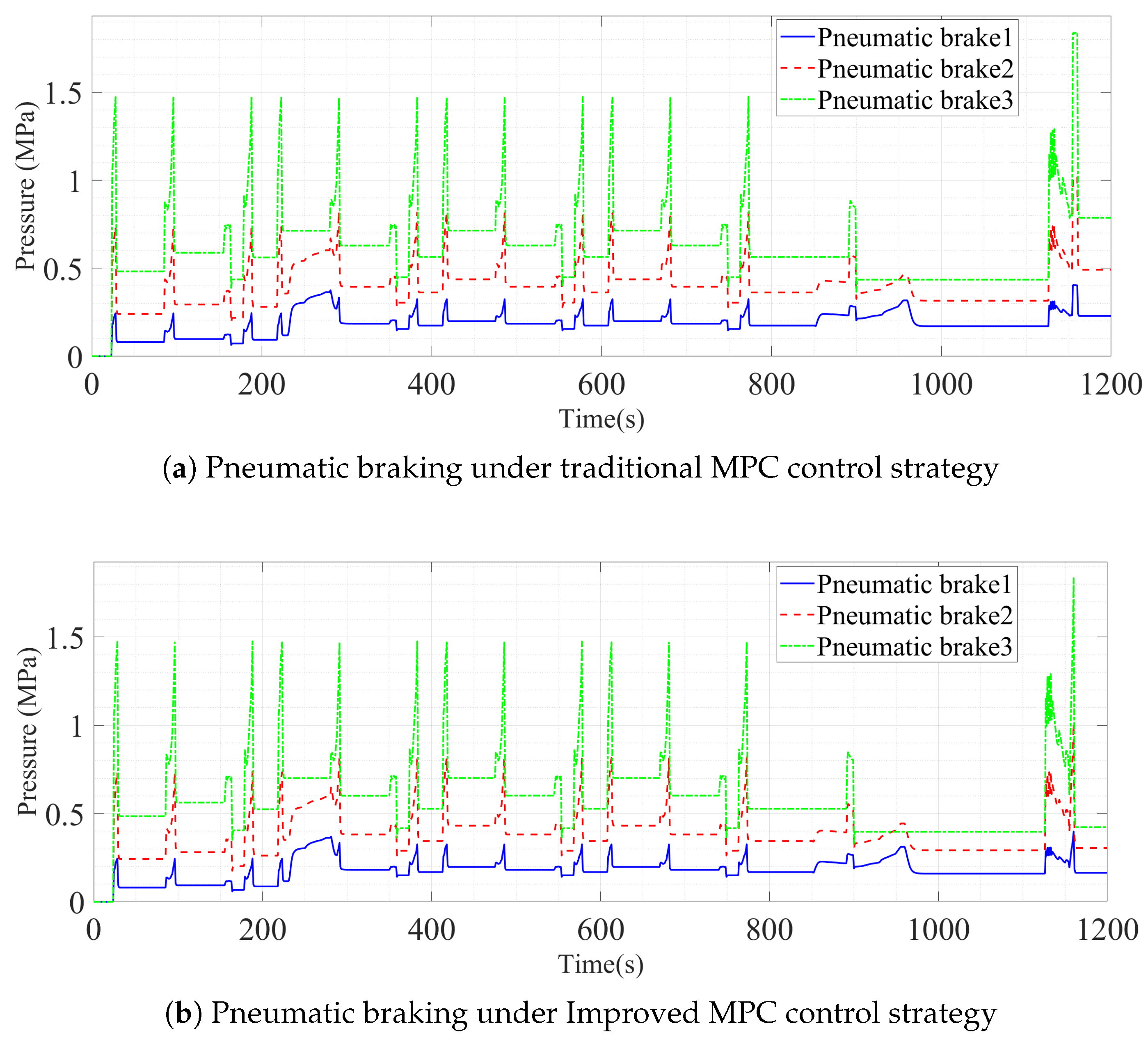

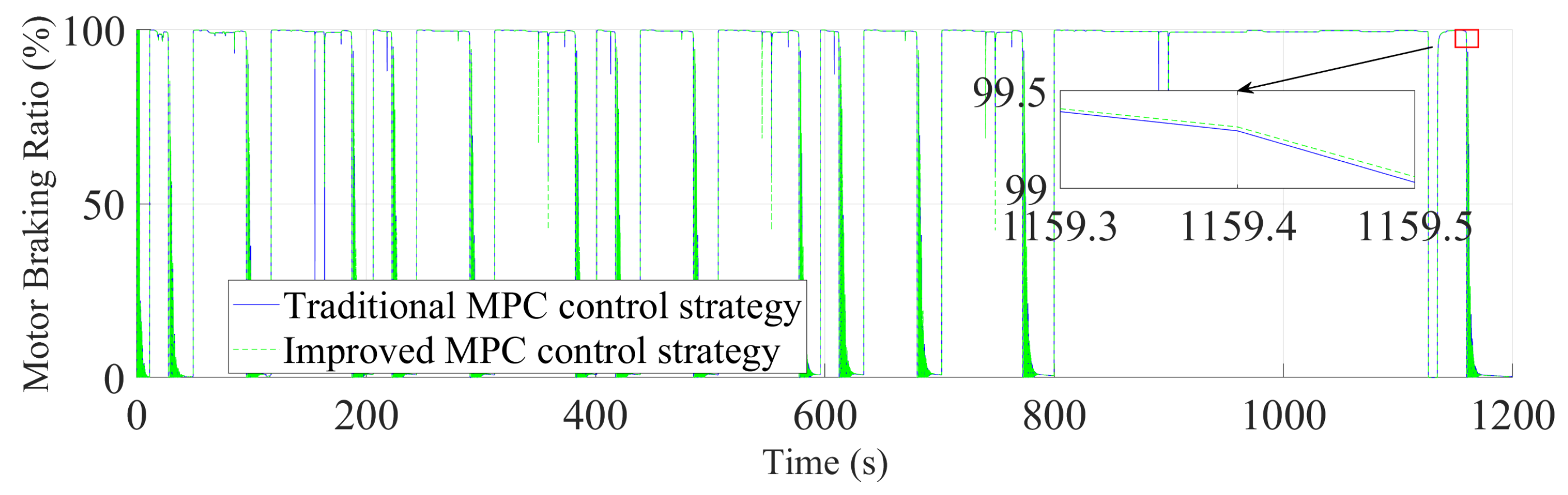

4.2. NEDC Driving Cycle Test

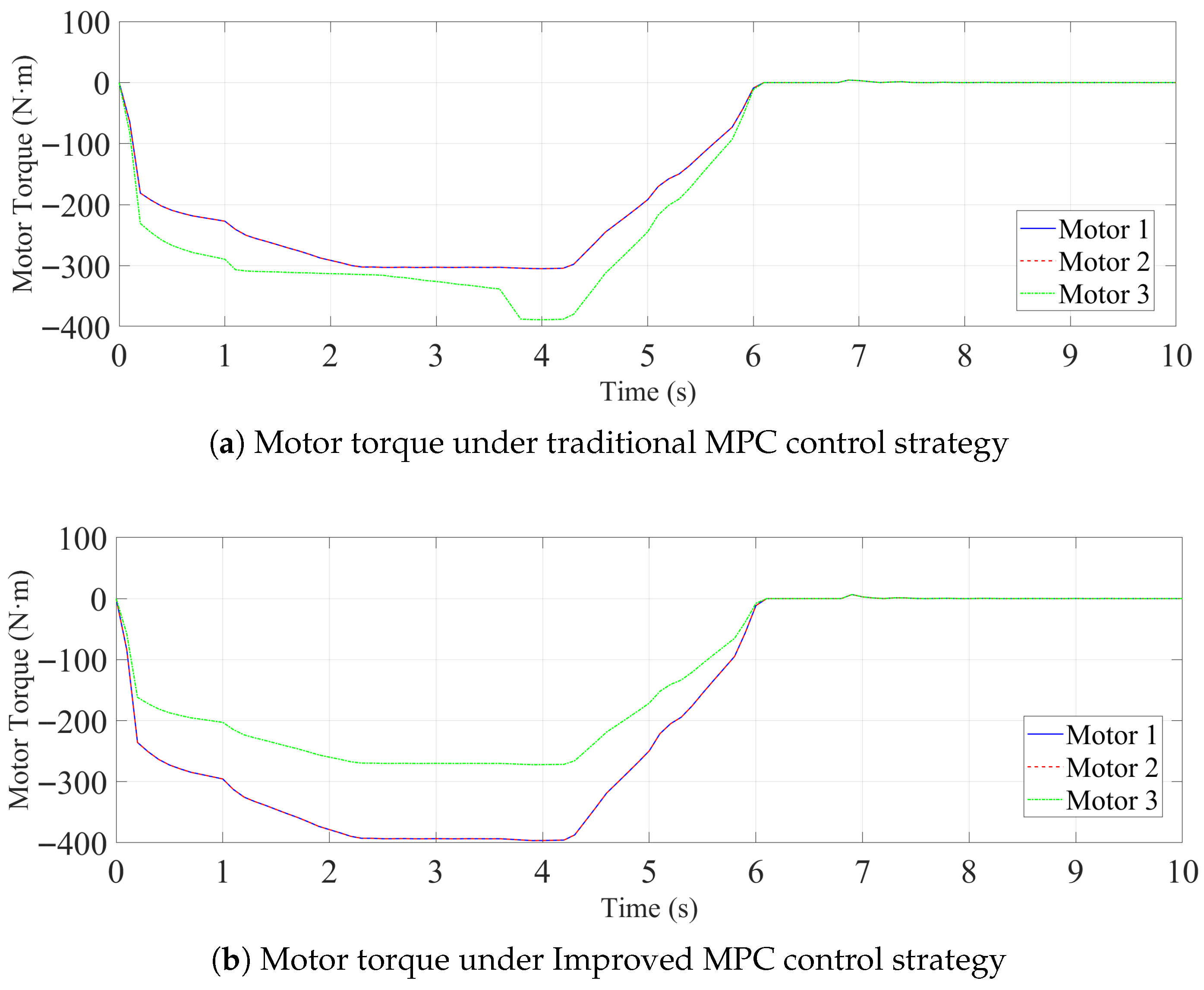

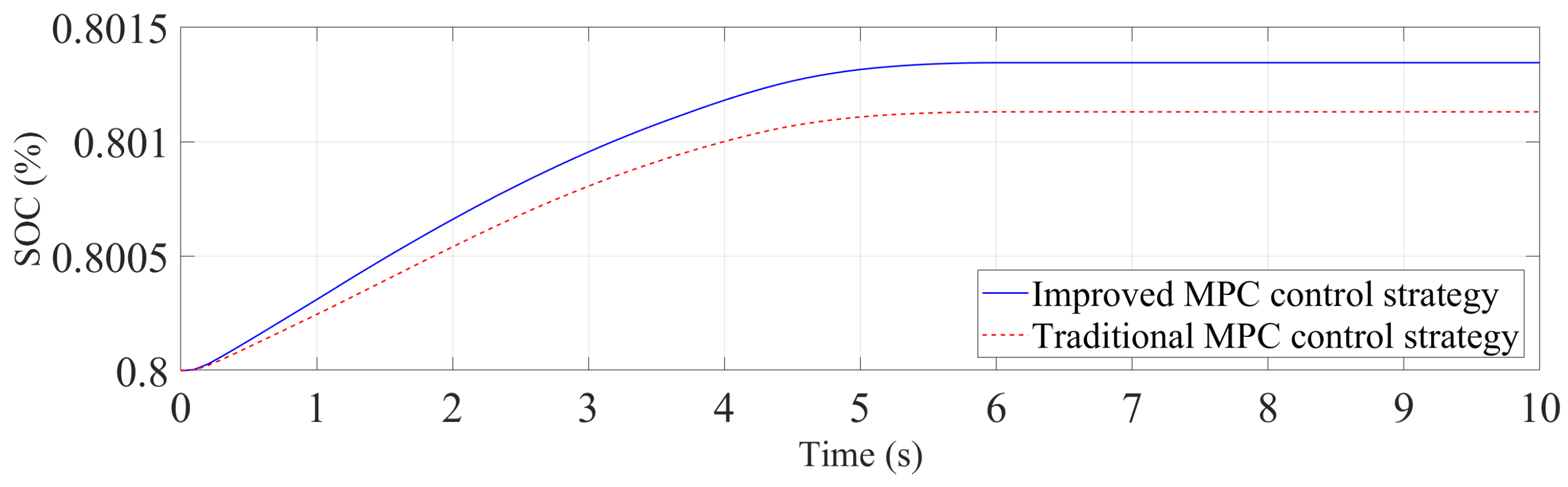

4.3. High-Intensity Braking Test

4.4. Summary of Simulation Results

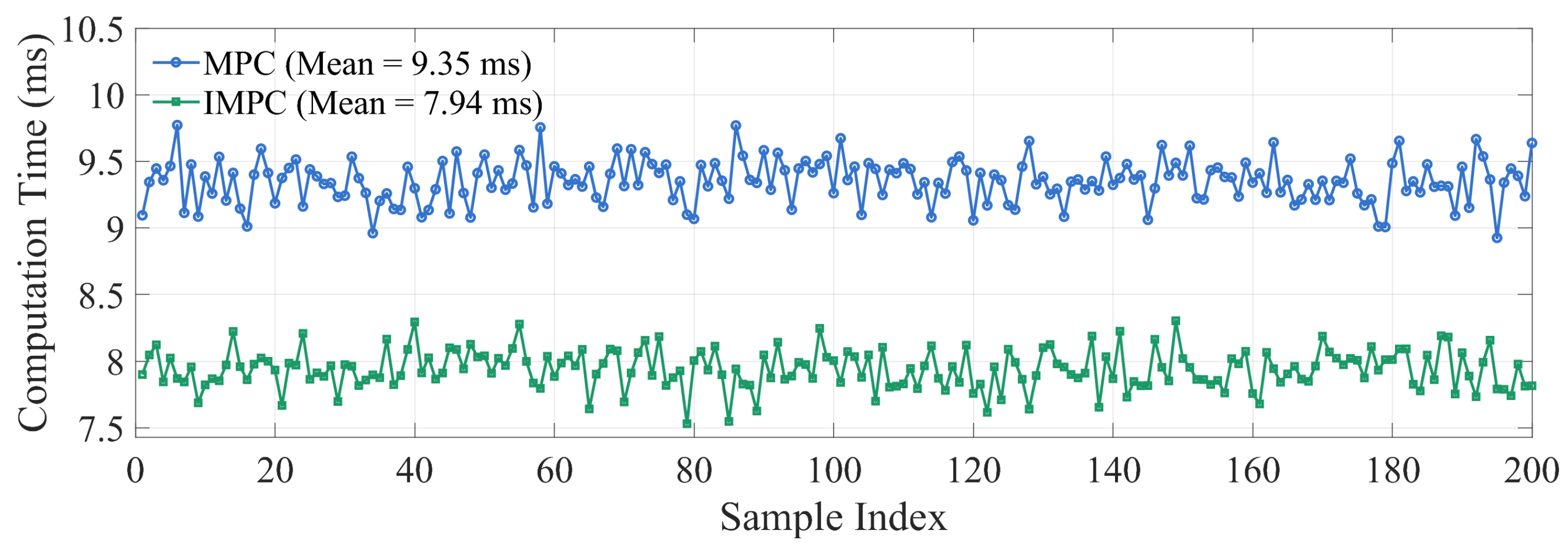

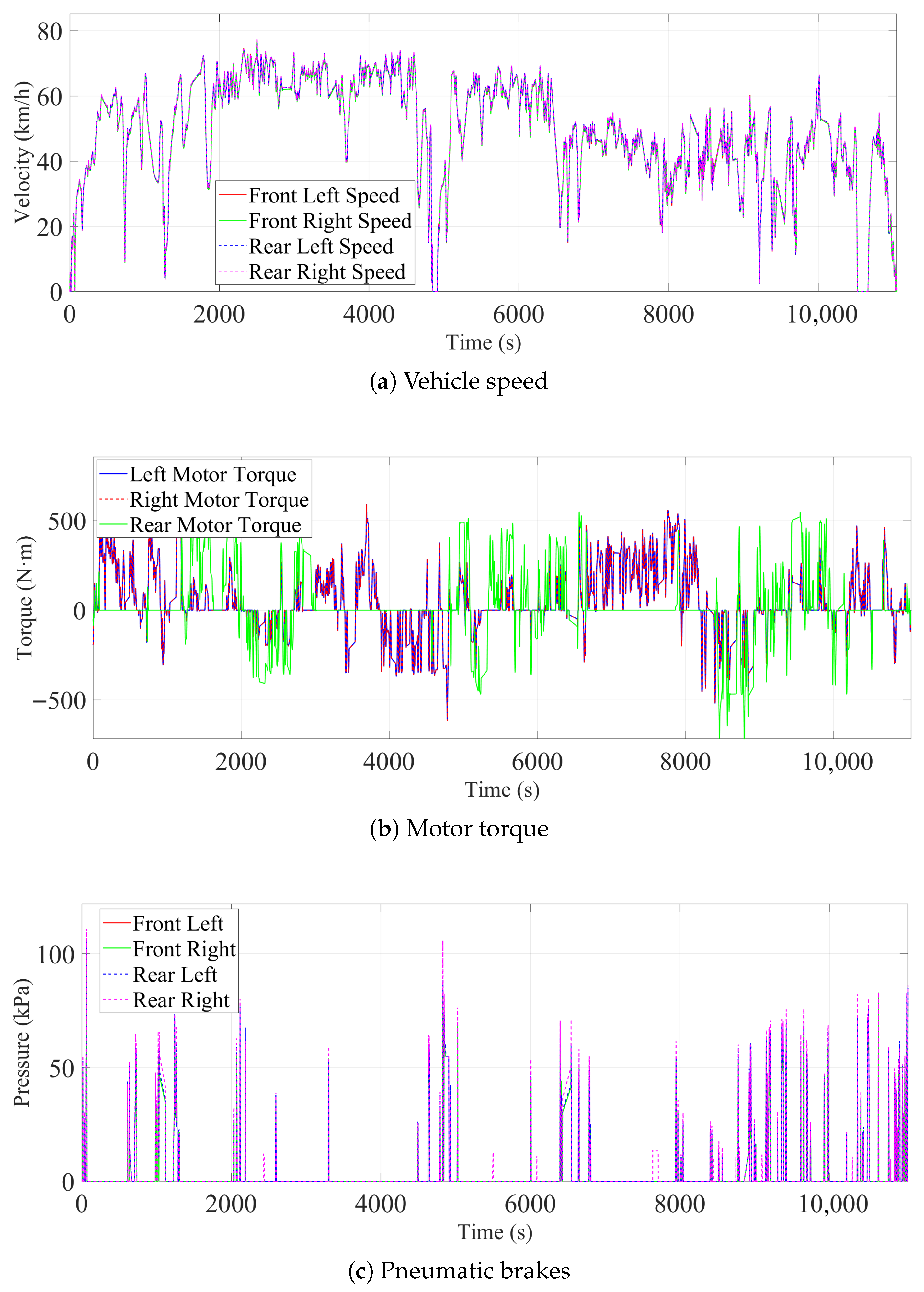

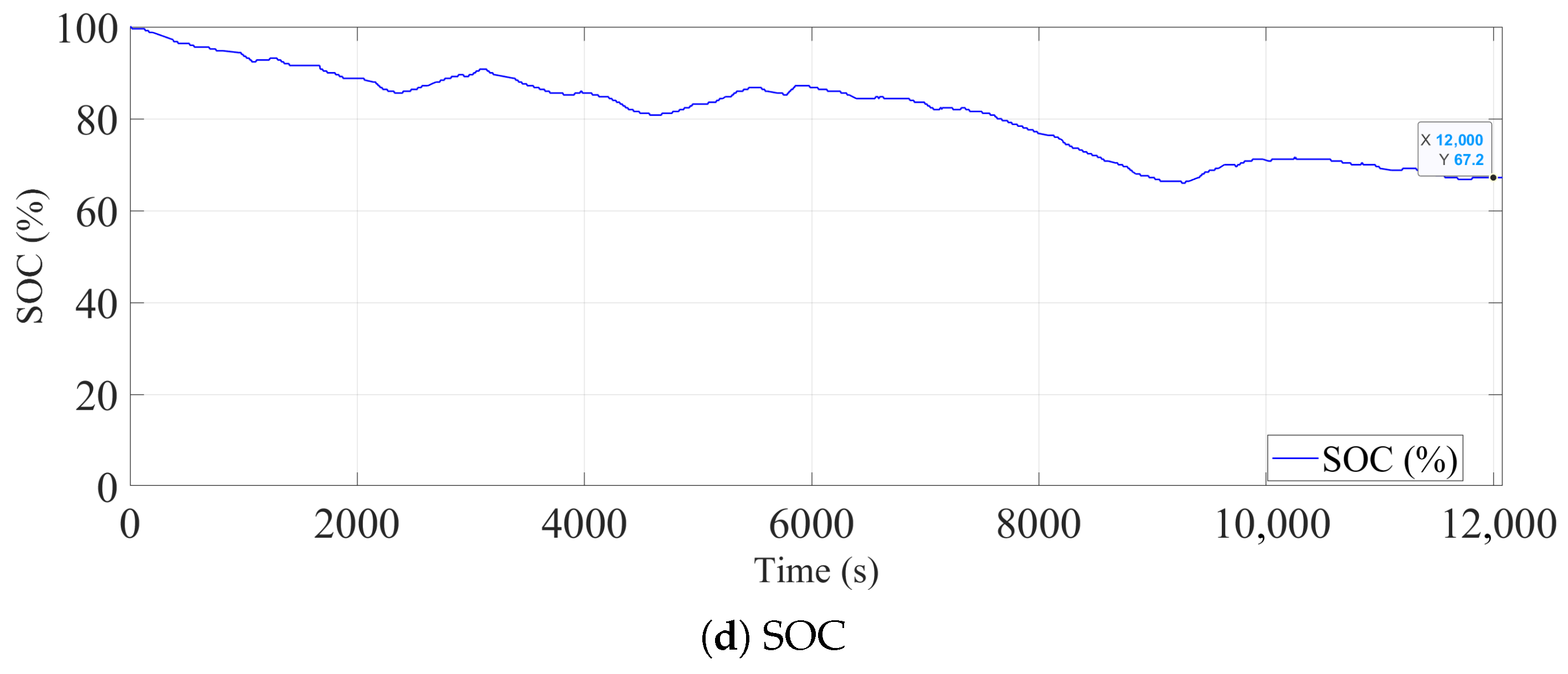

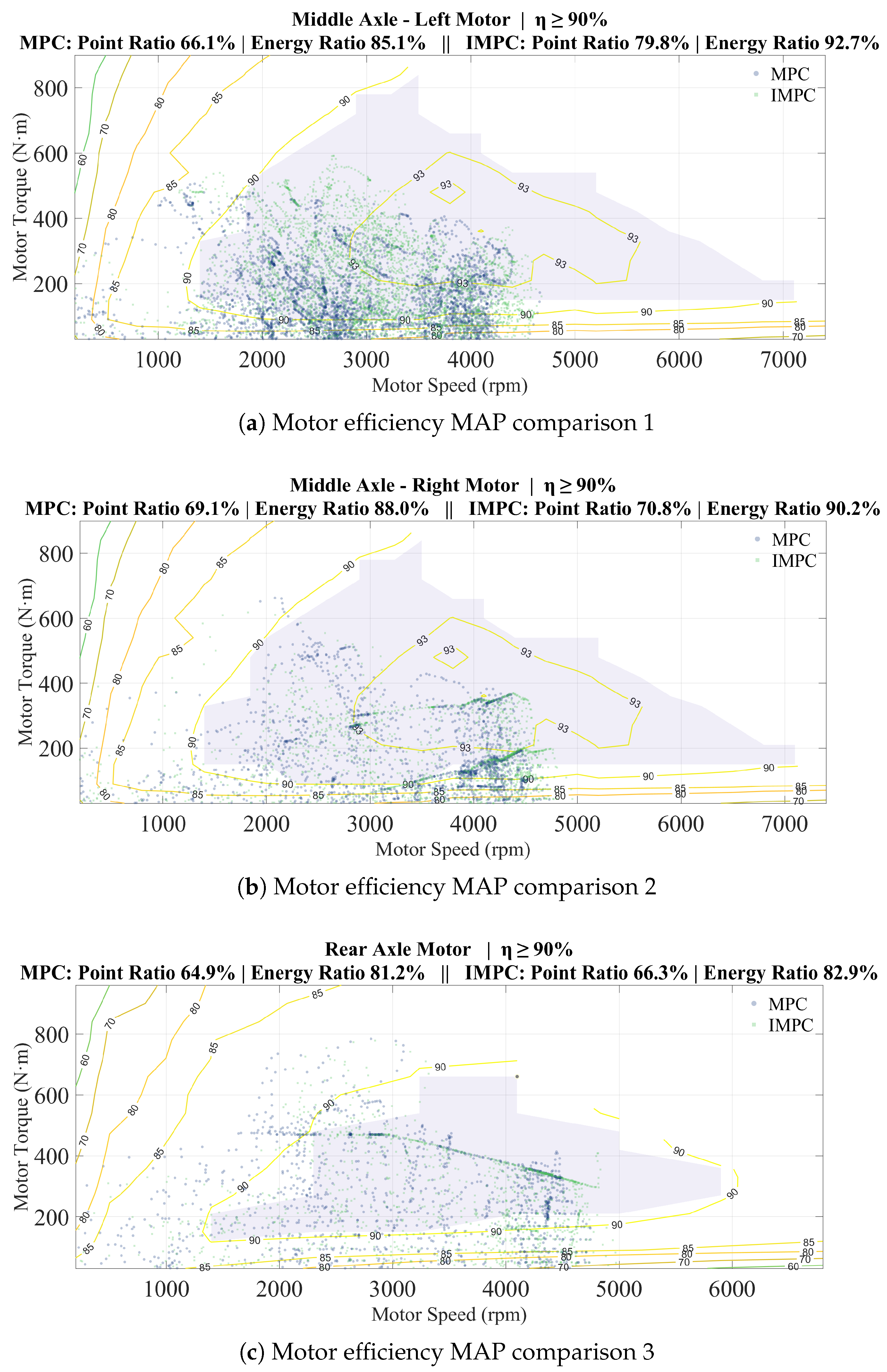

5. Real-Vehicle Verification

5.1. Experimental Setup

5.2. Experimental Results

6. Conclusions

Abbreviations

| CBF | Control Barrier Function |

| CG | Center of Gravity |

| CPU | Central Processing Unit |

| EKF | Extended Kalman Filter |

| EMB | Electro-Mechanical Brake (system) |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| IMPC | Improved Model Predictive Control |

| MAP | Motor Efficiency Map |

| MPC | Model Predictive Control |

| NEDC | New European Driving Cycle |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| RMSE | Root-Mean-Square Error |

| SOC | State of Charge |

| VCU | Vehicle Control Unit |

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hamada, A.T.; Orhan, M.F. An overview of regenerative braking systems. J. Energy Storage 2022, 52, 105033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, G.; Ke, J.; Liang, J.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Liu, Q.; Hao, C. Analysis of the Actual Usage and Emission Reduction Potential of Electric Heavy-Duty Trucks: A Case Study of a Steel Plant. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.Y.; Gong, D.H.; Huang, Z.G.; Yang, L. Life Cycle Carbon Reduction Benefits of Electric Heavy-Duty Truck to Replace Diesel Heavy-Duty Truck. Environ. Sci. 2024, 45, 3119–3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, T.A.; Monaghan, R.F.D. Techno-econo-environmental Comparisons of Zero- and Low-Emission Heavy-Duty Trucks. Appl. Energy 2022, 308, 118327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lin, Z.; Crawford, C.; Li, S. Techno-economic comparison of electrification for heavy - duty trucks in China by 2040. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2022, 102, 103152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahangir Samet, M.; Liimatainen, H.; van Vliet, O.P.R.; Pöllänen, M. Road Freight Transport Electrification Potential by Using Battery Electric Trucks in Finland and Switzerland. Energies 2021, 14, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardhi, S.; Chakraborty, S.; Tran, D.-D.; El Baghdadi, M.; Wilkins, S.; Hegazy, O. A Review of Fuel Cell Powertrains for Long-Haul Heavy-Duty Vehicles: Technology, Hydrogen, Energy and Thermal Management Solutions. Energies 2022, 15, 9557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lü, C.; Li, Y.; Gou, J.; He, C. Status Quo and Prospect of Regenerative Braking Technology in Electric Cars. Automot. Eng. 2014, 36, 911–918. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, X.; Yan, Z.; Prada, D.N.; Jia, G.; Popuri, S.S.; Vijayagopal, R.; Li, Y.; Sari, R.L.; Liu, C.; He, X.; et al. Life Cycle Economic and Environmental Assessment for Emerging Heavy-Duty Truck Powertrain Technologies in China: A Comparative Study of Battery Electric, Fuel Cell Electric, and Hydrogen Combustion Engine Trucks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 2018–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, C.S.N.; Subramanian, S.C. Cooperative control of regenerative braking and friction braking for a hybrid electric vehicle. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 2016, 230, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Yang, L.; Zhang, J.; Chen, C.; Gao, Q.; Liu, Y. Reinforcement Learning-Based Braking Energy Recovery Control Strategy for Multi-axle Electric Heavy-Duty Truck Vehicles. In Proceedings of 2024 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Autonomous Transportation; (AIAT 2024); Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2025; Volume 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Peng, M.; Huang, Z. A Novel Tire-Road Adhesion Stability Model and Control Strategy for Centralized Drive Pure Electric Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Nagoya, Japan, 11–17 July 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ma, J.; Zhao, X.; Wang, L. Study on Braking Energy Recovery Control Strategy for Four-Axle Battery Electric Heavy-Duty Trucks. J. Adv. Transp. 2023, 2023, 1868528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, D. Research on Optimal Driving Torque Control Strategy for Multi-Axle Distributed Electric Drive Heavy-Duty Vehicles. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wong, P.K.; Guo, R.; Sun, Z. Design of an Omnidirectional, Multi-Axle, Distributed-Drive Electric Truck with Mecanum Wheels and Direct Yaw Moment Controller. Int. J. Heavy Veh. Syst. 2024, 31, 721–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shi, C.; Lin, B.; Huang, H. Design and Steering Angle Control of Steering-by-Wire Hydraulic Systems for Multi-Axle Vehicles. China Mech. Eng. 2022, 33, 1741–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Song, J.; Zhang, Z. Electric Vehicle Braking Energy Recovery Control Method Integrating Fuzzy Control and Improved Firefly Algorithm. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0320537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, E.-H.; Shu, M.-H.; Huang, J.-C.; Lin, H.-T. Energy Recovery Decision of Electric Vehicles Based on Improved Fuzzy Control. Processes 2024, 12, 2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, Z.; Lv, W. Optimisation of Braking Energy Recovery for Rear-Drive Electric Vehicles Based on Fuzzy Control. Int. J. Veh. Des. 2023, 92, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F. A PMSM Fuzzy Logic Regenerative Braking Control Strategy for Electric Vehicles. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2021, 41, 4873–4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Huang, Z.; Xu, G. Regenerative Braking with Direct Adhesion Control for Distributed Drive Electric Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference (ITSC), Indianapolis, IN, USA, 19–22 September 2021; pp. 1664–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.J.; Zhang, Y.F. Research on Optimization Control Strategy for Braking Energy Recovery of a Battery Electric Vehicle Based on EMB System. Automot. Eng. 2022, 44, 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Yu, M.; Wang, Y.; Luo, Y. Long Short-Term Memory–Model Predictive Control Speed Prediction-Based Double Deep Q-Network Energy Management for Hybrid Electric Vehicle to Enhance Fuel Economy. Sensors 2025, 25, 2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hao, G. Energy-Optimal Adaptive Control Based on Model Predictive Control. Sensors 2023, 23, 4568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, J.; Ruan, S.; Wang, W. Model Predictive Control Based Energy Management Strategy of Series Hybrid Electric Vehicles Considering Driving Pattern Recognition. Electronics 2023, 12, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Q.; Meng, D.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Chu, H.; Gao, B. Torque Vectoring Control of Distributed Drive Electric Vehicles Using Fast Iterative Model Predictive Control. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2024, 58, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.L.; Huang, H.; Yang, L.; Wang, H.F.; Gao, T. Multi-Strategy Pelican Algorithm Optimized MPC Controller for Vehicle Trajectory Tracking. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. Available online: https://xuebao.sjtu.edu.cn/EN/10.16183/j.cnki.jsjtu.2024.316 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Li, D.F.; Zha, A.F.; Xu, B.; Zhang, J.J. Trajectory Tracking Control Algorithm of Emergency Collision Avoidance for Tractor Semi-trailer Combination. Automot. Eng. 2022, 44, 1098–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubbink, J.; Viljoen, R.; Aertbeliën, E.; Decrè, W.; De Schutter, J. From Instantaneous to Predictive Control: A More Intuitive and Tunable MPC Formulation for Robot Manipulators. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 10, 748–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.J.; Sun, B.B.; Zhang, T.Z.; Ni, M.; Lin, L.H.; Xu, H.G. Study of braking energy recovery control strategy for a dual motor pure electric all-terrain vehicle. Mod. Manuf. Eng. 2022, 12, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Wang, F.; Ye, P. Regenerative braking strategy of dual—Motor EV considering energy recovery and brake stability. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Li, G.; Wang, S. Research on Multi - Mode Braking Energy Recovery Control Strategy for Battery Electric Vehicles. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yong, S.Z.; Chen, Y. Stability Control of Autonomous Ground Vehicles Using Control-Dependent Barrier Functions. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2021, 6, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Liu, H.; Wang, P.; Gong, X. Integrated Longitudinal and Lateral Vehicle Stability Control for Extreme Conditions With Safety Dynamic Requirements Analysis. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 19285–19298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ai, Z.; Chen, J.; You, T.; Du, C.; Deng, L. Energy-Saving Optimization and Control of Autonomous Electric Vehicles With Considering Multiconstraints. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 52, 10869–10881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Chen, H.; Wang, J.; Zhao, H. Velocity optimization for braking energy management of in-wheel motor electric vehicles. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 66410–66422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.; Chang, C.; Zhao, D.; Xu, Y. Research on Cooperative Braking Control Algorithm Based on Nonlinear Model Prediction. World Electr. Veh. J. 2021, 12, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Zheng, Z. Research on Composite Braking Control Strategy of Battery Electric Vehicle Based on Road Surface Recognition. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D 2022, 238, 788–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.A.; Liang, C. Research on Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm of Electromechanical Hybrid Braking Control Strategy Based on Road Surface Recognition. Energy Sources Part A Recover. Util. Environ. Eff. 2022, 47, 2027580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Bu, L.; Fu, B.; Zheng, J.; Wang, G.; He, L.; Hu, Y. Research on Adaptive Distribution Control Strategy of Braking Force for Pure Electric Vehicles. Processes 2023, 11, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Xu, X. Lateral Stability Control of a Tractor–Semitrailer at High Speed. Machines 2022, 10, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Sun, L.; Zhao, J.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Song, Z. Research on Anti-lock Braking Control for Intelligent Multiple-axis Semi-trailer Based on Wheel Group Braking Force Different-phase Fluctuation Reconstruction. J. Mech. Eng. 2025, 61, 243–260. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter Name | Value | Unit | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | Unladen Vehicle Weight | 17,000 | kg |

| Gross Vehicle Weight | 49,000 | kg | |

| Wheelbase | 3600/1400 | mm | |

| Track Width | 2085/1880 | mm | |

| Wheel Radius | 530 | mm | |

| Motor | Rated Torque | 450 | Nm |

| Rated Speed | 3500 | rpm | |

| Peak Power | 346 | kW | |

| Battery | Rated Voltage | 800 | V |

| Battery Pack Capacity | 414 | KWh |

| MPC | IMPC | |

|---|---|---|

| RMSE | 1.1036 | 1.0232 |

| MPC | IMPC | |

|---|---|---|

| RMSE | 1.8667 | 1.7812 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cai, L.; Yan, P.; Yang, X.; Yang, L.; Liu, Y.; Huang, G.; Liu, S.; Fan, J. Braking Energy Recovery Control Strategy Based on Instantaneous Response and Dynamic Weight Optimization. Machines 2026, 14, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14010010

Cai L, Yan P, Yang X, Yang L, Liu Y, Huang G, Liu S, Fan J. Braking Energy Recovery Control Strategy Based on Instantaneous Response and Dynamic Weight Optimization. Machines. 2026; 14(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleCai, Lulu, Pengxiang Yan, Xiaopeng Yang, Liyu Yang, Yi Liu, Guanfu Huang, Shida Liu, and Jingjing Fan. 2026. "Braking Energy Recovery Control Strategy Based on Instantaneous Response and Dynamic Weight Optimization" Machines 14, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14010010

APA StyleCai, L., Yan, P., Yang, X., Yang, L., Liu, Y., Huang, G., Liu, S., & Fan, J. (2026). Braking Energy Recovery Control Strategy Based on Instantaneous Response and Dynamic Weight Optimization. Machines, 14(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14010010