1. Introduction

Electro-hydraulic servo pump-controlled systems are widely used in high-power density drive fields such as industrial machine tools [

1,

2,

3], engineering vehicles [

4,

5], aerospace [

6], and robotics [

7,

8], and are the core component of power transmission and control. Compared with valve-controlled hydraulic systems, pump-controlled hydraulic systems have the advantages of low noise, compact structure, high energy conversion efficiency, and reliability [

9,

10,

11]. In line with the themes of energy conservation and green manufacturing, pump-controlled systems have received increasing attention and become a current research hotspot [

12]. However, there exists an input delay phenomenon in electro-hydraulic servo pump-controlled systems which is caused by the sensor signal’s transmission delay, the controller’s operation period, the servo driver’s filtering algorithm, the current loop response speed in the electrical part, the moment of inertia and connection stiffness of the motor-pump unit in the mechanical part, and oil leakage in the hydraulic part [

13,

14]. Meanwhile, different from the pre-pressurization of valve control systems, the pressure build-up rate in pump-controlled systems is determined by the compression cavity volume, the oil’s bulk modulus, and the load, which leads to state delays in the process of pressure establishment [

15,

16]. The existence of input and state delays significantly degrades the performance of the pump-controlled system, causing oscillations, increased overshoot, slow responses, and even instability [

17]. These issues become the main obstacle to achieving high-precision control and rapid responses in pump-controlled hydraulic systems. Therefore, it is necessary to propose reasonable control methods to improve the system’s control performance degradation caused by time-delay phenomena and enhance the system’s transient and steady-state performance.

The inherently strong coupling among the electrical, mechanical, and hydraulic subsystems in electro-hydraulic servo pump-controlled systems introduces significant nonlinear behavior. These nonlinearities mainly include dead zones, time delays, and friction, which seriously impair the control accuracy and response speed of the system. To address these issues, relevant scholars have conducted extensive research on nonlinear control strategies to suppress nonlinear disturbances and improve system stability. The traditional PID controller has limited adjustable parameters and often fails to achieve satisfactory control performance due to the inherent nonlinearities and unavoidable uncertainties in hydraulic systems. To solve this problem, an intelligent PID controller is designed for the position control of a nonlinear electro-hydraulic system with uncertain valve characteristics and supply pressure variations in [

18], the results show that the controller achieves better tracking results against system uncertainties and external disturbances. In [

19], an adaptive robust motion control strategy is proposed to resolve the issue of nonlinear pump flow at low speeds for a direct-driven electro-hydraulic system with adaptive pump flow rate model compensation. A robust high-precision position control strategy incorporating leakage and friction compensation is designed for electro-hydrostatic actuators in [

20]; both the steady-state and transient position tracking performances achieve significant improvement. In [

21], an adaptive neural network control is designed to compensate for unknown system dynamics based on the backstepping control framework. Additionally, extended state observers are employed to address the disturbance and unknown dynamics. To improve the working performance of electro-hydrostatic actuators, a sliding-mode control strategy with a damping variable sliding surface is proposed in [

22]. The simulation and experimental results show that the controller exhibits strong overshoot suppression and robustness. Reference [

23] combines a modified backstepping algorithm with a special adaptation law to compensate for all nonlinearities and uncertainties in pump-controlled electrohydraulic actuators. In [

24], a position controller is built based on the quantitative feedback theory to satisfy the tracking, stability, and disturbance rejection specifications of electro-hydrostatic actuators. The results show great control performance over a wide range of parametric uncertainties. The above control methods effectively address the issue of control performance degradation in hydraulic systems caused by nonlinearity and uncertainty. However, robust control is inherently conservative, sliding-mode control suffers from chattering, and neural network control demands substantial real-time computation for online learning. More importantly, the design of these controllers fails to account for the effects of input and state delays.

Some control methods have been proposed to compensate for input and state delays such as the Smith predictor [

25] and the finite spectrum assignment method [

26]. However, these methods suffer from weak robustness and require high model accuracy. In recent years, several control schemes have been developed to enhance the control performance of nonlinear systems with input and state delays. A controller combining backstepping design and finite-time command filtering technology is proposed in [

27]; the results show the convergence of tracking errors and the boundedness of all closed-loop signals for nonlinear systems with input delays. An adaptive neural network controller is presented in [

28] to address the trajectory tracking problem for a class of strict-feedback nonlinear systems with state constraints and input delays. Although the aforementioned methods have achieved certain results in dealing with the time-delay phenomena, they fail to restrict the overshoot and convergence speed in the motion process. For switched nonlinear MIMO time-delay systems, an output–feedback method based on funnel control is proposed in [

29], ensuring that the tracking error remains within a pre-specified performance funnel. Prescribed performance control (PPC) is first proposed in [

30] to constrain the tracking error within a pre-defined bound with exponentially converging performance boundaries, which can achieve specific system performance requirements such as maximum overshoot, convergence rate, and steady-state error [

31,

32,

33,

34]. However, it is a significant challenge to directly apply PPC to electro-hydraulic servo pump control systems with input and state delays. This is primarily because the presence of delays tends to undermine the stability of error transformation. The Lyapunov–Krasovskii functional method and the Lyapunov–Razumikhin functional method can effectively handle input and state delays in nonlinear systems [

35,

36]. However, the computational complexity, conservatism, and the need for accurate mathematical models have hindered the widespread application of these functional methods in electro-hydraulic servo pump-controlled systems.

Inspired by the above discussion, combining PPC with the Lyapunov–Krasovskii method is a worthwhile exploration to address the position tracking problem of electro-hydraulic servo pump control systems with input and state delays. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows.

- (1)

The PPC method is introduced into the trajectory tracking of electro-hydraulic servo pump-controlled systems. A performance function is employed to precisely regulate the transient parameters (such as overshoot and convergence speed) of trajectory tracking errors. Through error transformation, the complex nonlinear control problem with state constraints is converted into a standard unconstrained nonlinear stabilization problem, simplifying the processes of controller design and stability analysis.

- (2)

A state transformation is designed to convert the system with time delays into a time-delay-free equivalent system. The combination of the backstepping control framework and PPC enhances the system’s robustness under input and state delay conditions.

- (3)

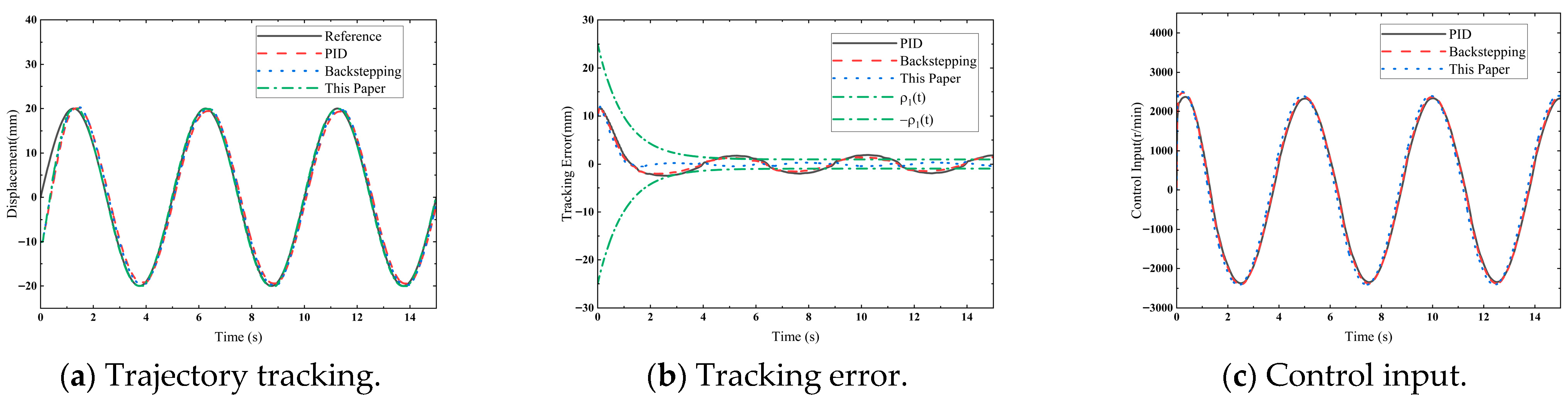

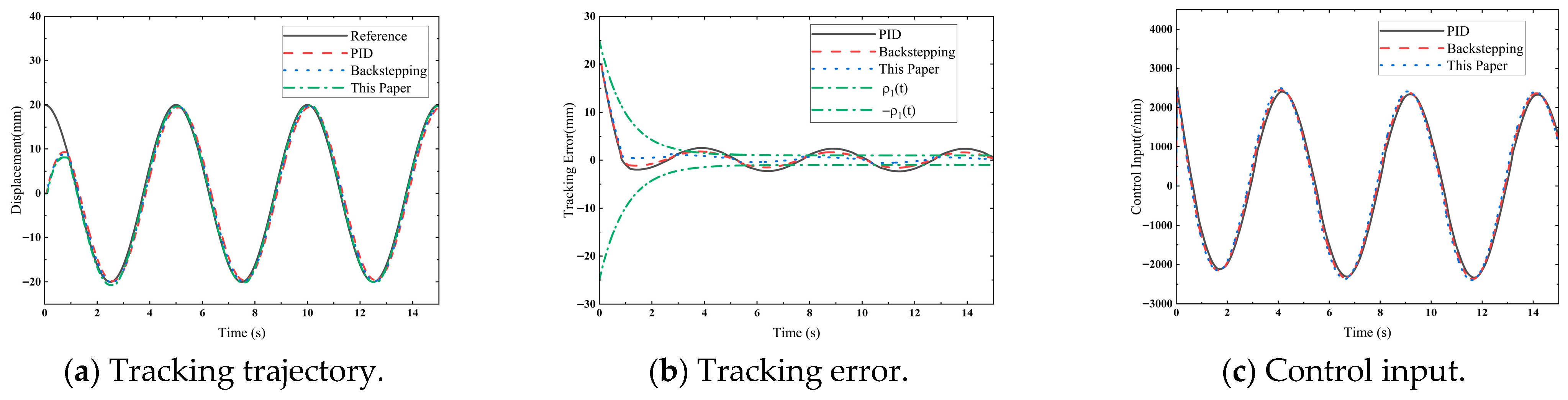

Through comparative experiments with traditional PID and backstepping control, the superiority and practical value of the proposed method in real systems have been verified.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents the mathematical model and problem formulation of the electro-hydraulic servo pump-controlled systems with input and state delays. The detailed design procedure of the prescribed performance trajectory tracking controller is elaborated in

Section 3.

Section 4 provides a rigorous stability analysis. The experimental results of

Section 5 verify the effectiveness of the proposed method. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Problem Statement

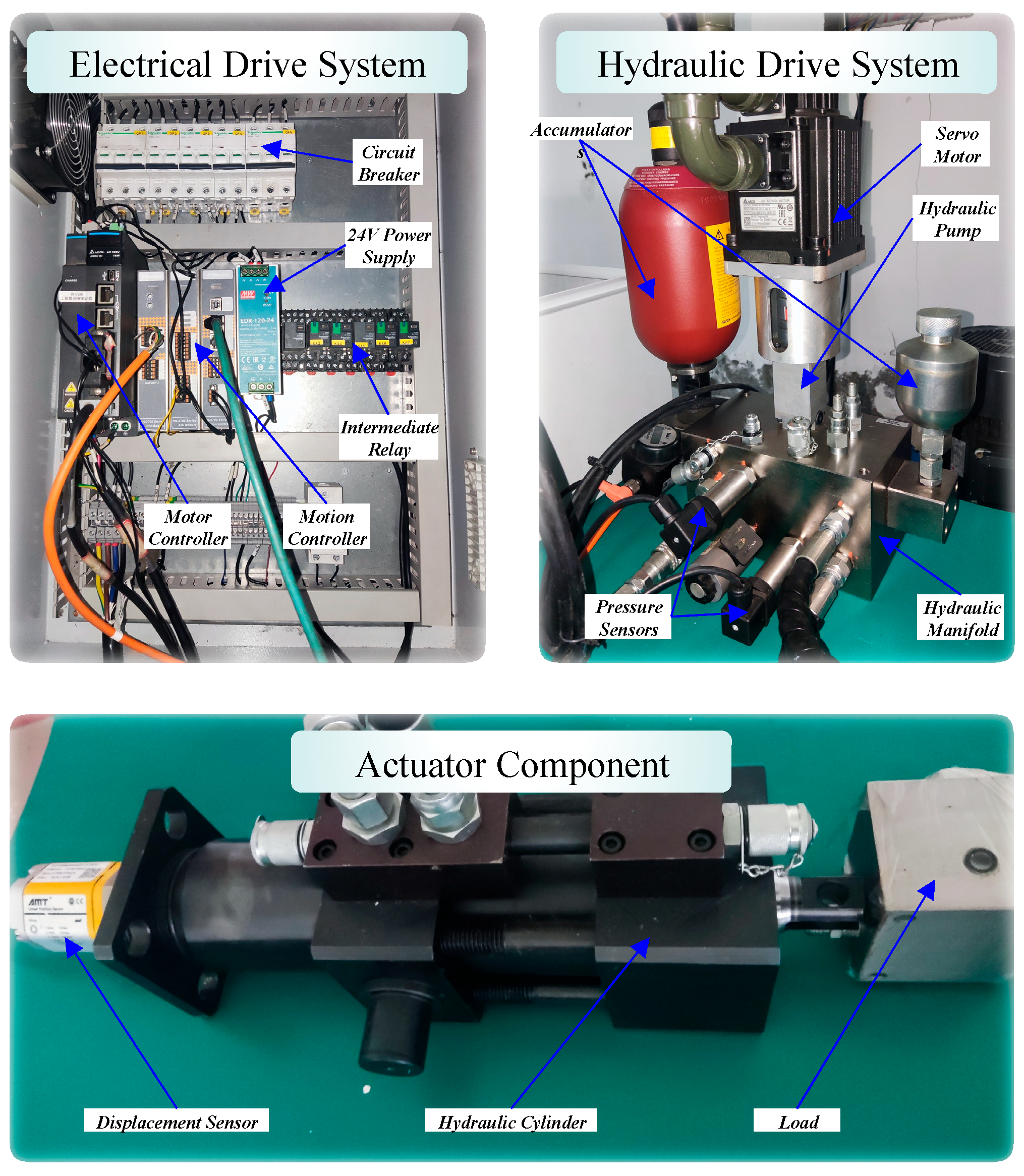

The working principle of electro-hydraulic servo pump-controlled systems involves controlling the flow rate and pressure supplied to the actuator by adjusting either the speed of the servo motor or the displacement of the hydraulic pump. Based on different control methods, electro-hydraulic servo pump-controlled systems can be divided into three types: fixed speed and variable displacement, variable speed and variable displacement, and variable speed and fixed displacement. Among these, although the first two types exhibit excellent transient and steady-state performance, they suffer from several drawbacks, including strict requirements for oil cleanliness, the complexity of variable-displacement mechanisms, and throttling or overflow losses. These issues not only reduce the system’s reliability and lower energy utilization efficiency but also limit its applicability in certain scenarios. By contrast, the variable speed and fixed displacement control mode has the advantages of a straightforward working principle, high energy efficiency, and low noise. Therefore, it serves as the primary research focus of this paper. Its working principle is illustrated in

Figure 1.

As shown in

Figure 1, the motor controller drives the servo motor to run a bidirectional fixed displacement hydraulic pump. By adjusting the speed of the servo motor, the flow rate and direction of hydraulic oil are regulated so that the oil enters the two chambers of the cylinder, which pushes the piston to move the load. A small auxiliary accumulator and the check valves are designed to maintain a low pressure in the system’s return lines and supplement internal leaks, which can prevent cavitation and ensure stable system operation. The function of the overflow valves is to prevent core components from bursting, sealing damage, or structural deformation due to overpressure. The feedback signals

,

,

from displacement or pressure sensors are compared with the command signal

in the motion controller. Then, the motion controller calculates the system input signal based on the tracking error and subsequently sends it to the motor controller. The motor controller converts the control signal into a high-voltage power signal capable of driving the motor and achieves precise regulation of motor speed.

The fixed displacement pump, serving as the hydraulic power source of the electro-hydraulic servo pump control system, supplies the system with pressure and flow. The flow continuity equation for the fixed displacement pump is formulated as follows.

Among these parameters, denotes the pump output flow, is the displacement of the fixed displacement pump, represents the motor speed, stands for the total leakage coefficient accounting for both internal and external leakage, refers to the load pressure defined as , and are the pressures in the two chambers of the hydraulic cylinder.

The hydraulic cylinder, serving as an actuator, regulates the displacement and velocity of the load, and its flow continuity equation is as follows.

Among these parameters, denotes the load-required flow, is the effective working area of the hydraulic cylinder, is the piston displacement, and represents the cylinder’s leakage coefficient. stands for the hydraulic cylinder’s effective volume and refers to the oil’s bulk modulus of elasticity.

Considering only the inertia load, the load force balance equation of the hydraulic cylinder can be written as follows.

where

is the mass of load. Neglecting the overall effect of the interconnecting volume between the hydraulic pump and hydraulic cylinder, we have

. Assuming

are constants, and defining state variable

, then the state space equation of the electro-hydraulic servo pump-controlled system is established as follows.

where

are known nonlinear functions and can be defined as follows.

The above equation captures the dynamic characteristics of the electro-hydraulic servo pump-controlled system. However, it ignores the negative impact caused by time delays. Several factors in the electrical control process contribute to system input delay, including sensor signal transmission, the computational load of the control algorithm, the response speed of the motor controller, and the motor’s moment of inertia. Meanwhile, during the hydraulic transmission process, the state delays are mainly caused by the coupling effect between the hydraulic chamber and the load. On one hand, an excessively large hydraulic chamber volume reduces system stiffness and prolongs the pressure build-up process; on the other hand, the dynamic characteristics of the load directly influence the pressure build-up process. These two factors collectively result in significant state delays. Therefore, considering the input and state delays of the electro-hydraulic servo pump-controlled system, the state space equation can be modified as follows.

where

are known time-delay constants.

Assumption 1. The system states satisfy , where are positive constants. The target trajectory satisfies for .

Remark 1. The boundedness assumption on the system states and the desired trajectory is not arbitrary but grounded in the physical realities of the electro-hydraulic servo pump-controlled systems. The displacement is inherently bounded by the finite stroke length of the hydraulic cylinder. The velocity is bounded by the maximum flow rate deliverable by the fixed-displacement pump, which is determined by the pump’s displacement and the servo motor’s maximum speed. The state is bounded by the preset cracking pressure of the system’s relief valves, which serves as a fundamental safety feature. The desired trajectory is always designed to be bounded and physically achievable in practice. Therefore, Assumption 1 is not only mathematically convenient but also physically justified and holds for all practical operations of the system.

Remark 2. The dynamic model established in this paper focuses on the dominant dynamics and time-delay effects of the system, without explicitly including complex nonlinearities such as friction, changes in the fluid elastic modulus, and pipeline dynamics. We recognize that these unmodeled dynamics can be viewed as bounded uncertainties acting on the system. However, the core advantage of the PPC framework proposed in this paper lies in its inherent robustness to such bounded uncertainties by directly defining the boundaries of tracking errors. The experimental results show that even with these model simplifications, the designed controller can still ensure that the system states are uniformly bounded and the tracking error converges within the preset performance boundary, which fully verifies the effectiveness of the proposed method in practical applications.

3. Controller Design

PPC predefines the overshoot, convergence rate, and steady-state error of the system through a performance function and incorporates a nonlinear error transformation to ensure that the tracking error remains within the predefined bounds. The backstepping method is suitable for strict-feedback nonlinear systems. Its design follows a “recursive procedure from the outer loop to the inner loop”, which means starting from the outermost subsystem to recursively design virtual control variables to stabilize each level subsystem in sequence. Finally, the real control variables are obtained at the innermost layer to achieve global stability of the system. In this section, the backstepping method is adopted as the design framework, and the performance functions and error transformations of PPC are incorporated into the control law design for each subsystem. This enables the achievement of stability and convergence for the displacement, velocity, and pressure states of the electro-hydraulic servo pump-controlled systems with input and state delays. The design steps of the controller are shown below.

To map the normalized error from

onto the entire real axis

, a monotonically increasing nonlinear mapping function

is defined as follows.

where

and

,

.

Step 1: The performance function

of the first-order system is proposed as follows:

where

is the initial value of the performance function, specifying the maximum allowable overshoot;

is its steady-state value, defining the system’s maximum allowable steady-state error; and

is its decay rate, setting the minimum convergence rate for the tracking error.

The first-order control law is designed as

where

is the control parameter.

Step 2: The performance function

of the second-order system is proposed as follows:

where

is the initial value of the performance function, specifying the maximum allowable overshoot;

is its steady-state value, defining the system’s maximum allowable steady-state error; and

is its decay rate, setting the minimum convergence rate for the tracking error.

The second-order control law is designed as

where

is the control parameter.

Step 3: The performance function

of the third-order system is proposed as follows:

where

is the initial value of the performance function, specifying the maximum allowable overshoot;

is its steady-state value, defining the system’s maximum allowable steady-state error; and

is its decay rate, setting the minimum convergence rate for the tracking error.

The third-order control law is designed as follows.

where

is the control parameter.

To implement the control laws on the motion controller, the discretized form of control law (9) can be expressed as follows.

where

is the sampling period of the motion controller and

k is the index of the discrete time series.

The discretized form of control law (11) can be expressed as follows.

The discretized form of control law (13) can be expressed as follows.

where

and

are integer multiples of

with

.

To define the behavior of the controller when

, set the historical initial value of the controller as

for all

. Then,

where

are constants.

4. Stability Analysis

The coordinate transformation for the state variables of the electro-hydraulic servo pump-controlled system is as follows.

Then, the state-space representation (6) can be transformed as follows.

The normalized errors are defined as follows.

By substituting Equations (18) and (20) into (9), (11), and (13), the control laws are transformed as follows.

For the subsequent analysis, we define the following transformed errors.

Then, the control laws can be transformed as follows.

Further, the derivative of normalized errors can be expressed as follows.

Define an open set , and when the normalized errors , in Equation (20) satisfy , the tracking error of the system achieves the predetermined performance requirements. However, it is difficult to directly prove , so the nonlinear mapping function is introduced to convert the error region to . Based on the properties of the , when the transformed errors , are bounded, the normalization errors , are included in , and the stability of the system can be proven. From Assumption 1, we have for . According to the existence and uniqueness theorem for ordinary differential equation solutions, there exists a finite escape time such that for all .

Based on the above discussion, we now utilize the backstepping framework to prove the boundedness of all signals in the closed-loop system after error transformation, thereby establishing that the tracking error converges with prescribed performance.

Step 1: The Lyapunov function constructed for the first-order system is as follows:

By substituting Equations (12), (13), and (18) into the differential of Equation (25), we can obtain

In Equation (26),

for

can be obtained from the above discussion, and based on the definition of

, we can obtain

for

. Then, it can be concluded that

for

.

are set as bounded. Define

and there exists a positive constant

, such that

for

. Then,

satisfies the following inequality.

From Equation (27), we can obtain

when

; thus,

Combining Equations (22) and (28), the range of conversion tracking errors can be concluded as follows.

By Equations (21) and (29), it can be concluded that the control law is bounded. From Equations (7), (21), and (29), we can obtain , where . Hence, is bounded for .

Step 2: The Lyapunov function constructed for the second-order system is as follows:

By substituting Equations (12), (13), and (18) into the differential of Equation (30), we can obtain

In Equation (31),

for

can be obtained from the above discussion, and based on the definition of

, we can obtain

for

. Then, it can be concluded that

for

.

are set as bounded. Define

and there exists a positive constant

, such that

for

. Then,

satisfies the following inequality.

From Equation (32), we can obtain

when

; thus,

When Equations (22) and (33) are combined, the range of conversion tracking errors can be concluded as follows.

By Equations (21) and (34), it can be concluded that the control law is bounded. From Equations (7), (21), and (34), we can obtain , where . Hence, is bounded for . The control laws are bounded for according to Equation (21); thus, , , and are bounded for .

Step 3: The Lyapunov function constructed for the third-order system is as follows:

By substituting Equations (12), (13), and (18) into the differential of Equation (35), we can obtain

In Equation (36),

for

can be obtained from the above discussion, and based on the definition of

, we can obtain

for

. Then, it can be concluded that

for

.

are set as bounded. Define

and there exists a positive constant

, such that

for

. Then,

satisfies the following inequality.

From Equation (37), we can obtain

when

; thus,

Combining Equations (22) and (38), the range of conversion tracking errors can be concluded as follows.

By Equations (21) and (39), it can be concluded that the control law is bounded. From Equations (7), (21), and (39), we can obtain , where . Hence, is bounded for . Owing to Equation (21), the control laws are bounded for ; thus, , , and are bounded for .

According to Equations (29), (34), and (39), we can obtain that the normalized errors

, to satisfy

. Therefore, it can be concluded as follows with

extending to

.

By performing inverse transformation based on Equation (18), it can be concluded for

that

where

.

In summary, when the proposed control laws (9), (11), and (13) are applied to the electro-hydraulic servo pump-controlled system, the tracking error of the system can achieve prescribed performance convergence, and the proof for this conclusion is completed.