Automotive Scratch Detection: A Lightweight Convolutional Network Approach Augmented by Generative Adversarial Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We construct a novel, high-quality surface scratch dataset for automotive components, covering diverse real-world industrial scenarios. This dataset provides a solid benchmark for training and evaluating scratch detection models, supporting both current applications and future research in automotive defect detection.

- To alleviate the critical bottleneck of scarce annotated samples in surface scratch detection, we propose a comprehensive data augmentation framework leveraging a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) for synthesizing high-fidelity defect images, thereby significantly enhancing the diversity and size of the training dataset.

- We propose a lightweight CNN for surface scratch detection, replacing traditional parameter-heavy FC layers with 1D convolutions, significantly reducing model size while maintaining high accuracy for real-time industrial deployment.

- Extensive experimental evaluations conducted on practical industrial datasets validate the superior accuracy, robustness, and generalization capability of the proposed data-driven strategies and network architecture compared with existing approaches.

2. Dataset Construction and Preprocessing

2.1. Problem Statement and Dataset Establishment

2.2. Data Acquisition and Processing

2.2.1. Data Acquisition

2.2.2. Image Pre-Processing

2.3. Data Augmentation and Generation

2.3.1. Data Augmentation

2.3.2. Data Generation

3. Scratch Recognition with CNN

3.1. System Model

3.2. Lightweight Convolutional Neural Network Architecture

3.3. Recognition Algorithm

| Algorithm 1 Training Algorithm of the CNN-Based Scratch Detection Model for Automotive Components. |

|

| Algorithm 2 Model Testing and Scratch Detection for Automotive Components |

|

4. Numerical Results

4.1. Parameters Setting

4.2. Experimental Results and Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, H.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, T. A review of artificial intelligent methods for machined surface roughness prediction. Tribol. Int. 2024, 199, 109935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Fang, F.; Yan, N.; Wu, Y. State of the art in defect detection based on machine vision. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf.-Green Technol. 2022, 9, 661–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Zhang, X.; Yang, L.; Liu, H. An improved Sobel edge detection. In Proceedings of the 2010 3rd International Conference on Computer Science and Information Technology, Chengdu, China, 9–11 July 2010; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 5, pp. 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, L.; Goshtasby, A. On the Canny edge detector. Pattern Recognit. 2001, 34, 721–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Kong, J.Y.; Wang, X.D.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, G. Improved Sobel algorithm for defect detection of rail surfaces with enhanced efficiency and accuracy. J. Cent. South Univ. 2016, 23, 2867–2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathabadi, H. Novel filter based ANN approach for short-circuit faults detection, classification and location in power transmission lines. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2016, 74, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huangpeng, Q.; Zhang, H.; Zeng, X.; Huang, W. Automatic visual defect detection using texture prior and low-rank representation. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 37965–37976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, S.; Venugopal, V.; Kumar, M.; Anand, S. Deep learning-based image segmentation for defect detection in additive manufacturing: An overview. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 134, 2081–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Rao, L.; Ma, C.; Wei, K.; Ding, M.; Shi, L. Toward efficient and secure object detection with sparse federated training over internet of vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 14507–14520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R. Fast r-cnn. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1440–1448. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2015, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. Ssd: Single shot multibox detector. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Song, K.; Meng, Q.; Yan, Y. An end-to-end steel surface defect detection approach via fusing multiple hierarchical features. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2019, 69, 1493–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Hao, X.; Liang, L.; Liu, W.; Qin, C. A novel deep convolutional neural network algorithm for surface defect detection. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2022, 9, 1616–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Yan, F.; Lu, Y.; Wang, K.; Guo, S.; Zhang, T.; Pang, Y.; Niu, J.; Xu, M. Joint Attention-Guided Feature Fusion Network for Saliency Detection of Surface Defects. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, L.; Wu, C.; Cui, Z.; Niu, C. A new lightweight deep neural network for surface scratch detection. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 123, 1999–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Nie, G.; Gao, W.; Liao, M. 2D Semantic segmentation: Recent developments and future directions. Future Internet 2023, 15, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, C.; Aranda, C.; Galar, M. Guidelines to compare semantic segmentation maps at different resolutions. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 3431–3440. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.C.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K.; Yuille, A.L. Semantic image segmentation with deep convolutional nets and fully connected crfs. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.7062. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.; Jayasumana, S.; Romera-Paredes, B.; Vineet, V.; Su, Z.; Du, D.; Huang, C.; Torr, P.H. Conditional random fields as recurrent neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1529–1537. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, G. Automatic pixel-level multiple damage detection of concrete structure using fully convolutional network. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2019, 34, 616–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Wang, K.; Zhang, G.; Li, Z.; Zhu, C. Efficient and accurate semi-supervised semantic segmentation for industrial surface defects. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyene, D.A.; Maru, M.B.; Kim, T.; Park, S.; Park, S. Unsupervised domain adaptation-based crack segmentation using transformer network. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 80, 107889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qin, Y.; Lin, Z.; Xia, H.; Wang, C. Detection of scratch defects on metal surfaces based on MSDD-UNet. Electronics 2024, 13, 3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, G.; Wang, W.; Chen, J.; Jiang, X.; Yuan, H.; Huang, Z. A defect detection method for industrial aluminum sheet surface based on improved YOLOv8 algorithm. Front. Phys. 2024, 12, 1419998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajec, P.; Rožanec, J.M.; Theodoropoulos, S.; Fontul, M.; Koehorst, E.; Fortuna, B.; Mladenić, D. Few-shot learning for defect detection in manufacturing. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 6979–6998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Qiu, T.; Ma, C.; Ni, Y.; Yuan, L.; Zhou, X.; Li, J. On Traffic Prediction with Knowledge-Driven Spatial-Temporal Graph Convolutional Network aided by Selected Attention Mechanism. IEEE Trans. Mach. Learn. Commun. Netw. 2025, 3, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Hong, T. Few-shot defect detection in industrial scenarios: A comprehensive review of challenges, advances, and frontier trends. In Proceedings of the MATEC Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Ulis, France, 2025; Volume 413, p. 04005. [Google Scholar]

- De Noni, L.; Marjuban, S.M.H.; Andena, L.; Noh, K.; Li, Y.; Vollenberg, P.; Sue, H.J. Effect of color on scratch and mar visibility of polymers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2023, 140, e53699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ding, Y.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, E.; Wu, Z.; Shao, L. Surface defect detection methods for industrial products: A review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Wang, D.; Wu, H. Defect Detection Method for Large-Curvature and Highly Reflective Surfaces Based on Polarization Imaging and Improved YOLOv11. Photonics 2025, 12, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Pan, X.; Mi, C.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J.; Chen, P.; Wang, B. RDDPA: Real-time Defect Detection via Pruning Algorithm on Steel Surface. ISIJ Int. 2024, 64, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial networks. Commun. ACM 2020, 63, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Yang, C.; Mei, Z.; Zhou, X.; Shi, L.; Li, J. On joint optimization of trajectory and phase shift for IRS-UAV assisted covert communication systems. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 12873–12883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Bai, Y.; Mei, Z.; Zhang, S.; Ni, Y.; Shi, L.; Shu, F. Adversarial Machine Learning Assisted Hybrid Chaotic Covert Communication in OFDM with Subcarrier Index Modulation. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2025, 73, 11154–11169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Liu, X.; Hsieh, C.J. Improving the speed and quality of gan by adversarial training. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2008.03364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, F.; Shen, L.; Jie, Z.; Zhang, W.; Liu, W. A sufficient condition for convergences of adam and rmsprop. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 11127–11135. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.C. Mobilenetv2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 4510–4520. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; pp. 6105–6114. [Google Scholar]

- Koonce, B. SqueezeNet. In Convolutional Neural Networks with Swift for Tensorflow: Image Recognition and Dataset Categorization; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 73–85. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. Efficientdet: Scalable and efficient object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 10781–10790. [Google Scholar]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, T.; Li, Z.; Xiao, X.; Guo, Z.; Ning, W.; Ding, T. Cascaded detection method for surface defects of lead frame based on high-resolution detection images. J. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 72, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

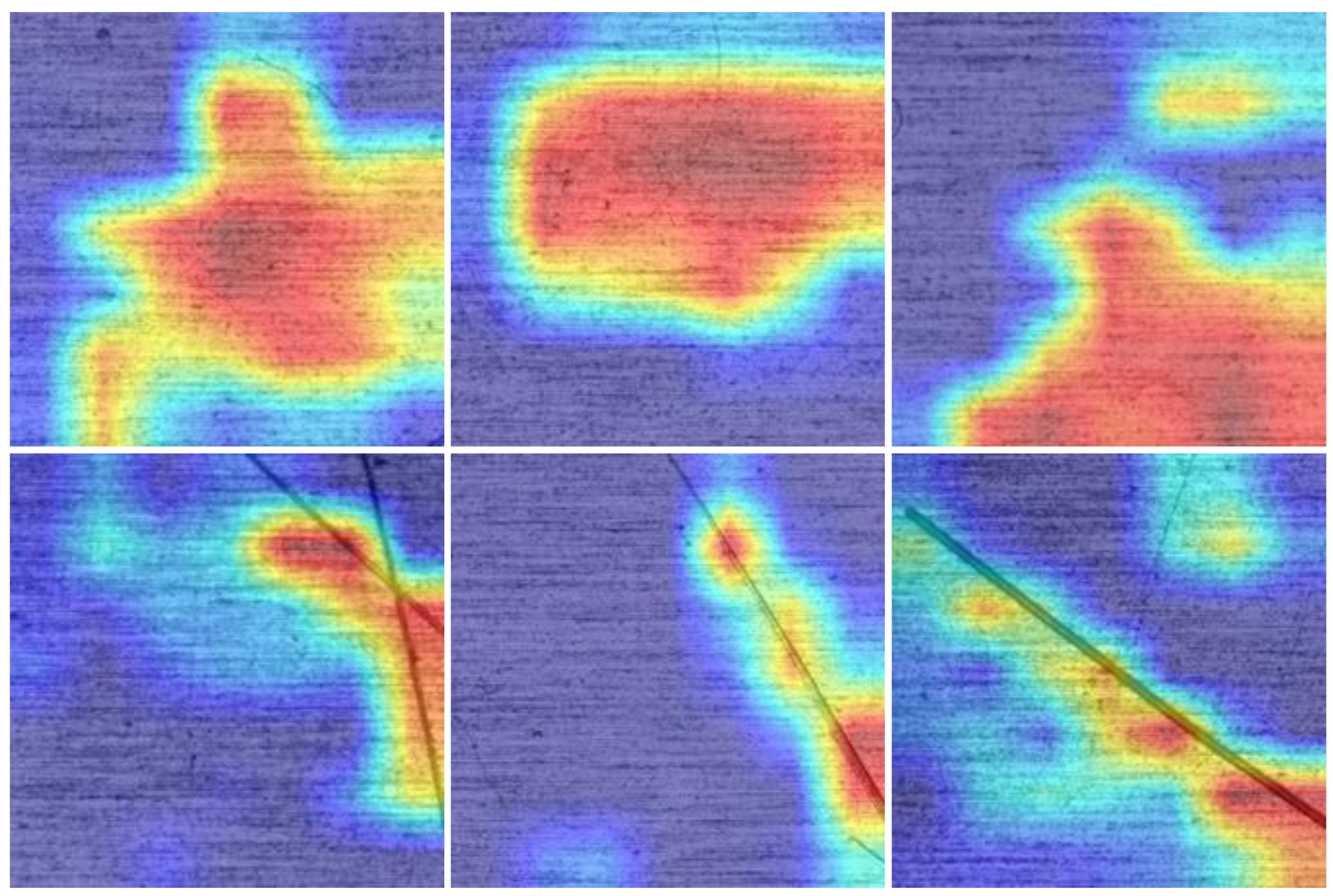

- Zhou, B.; Khosla, A.; Lapedriza, A.; Oliva, A.; Torralba, A. Learning deep features for discriminative localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2921–2929. [Google Scholar]

| Feature Input | Operation Type | Pooling Kernel | Feature Output | Parameter Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 112 × 112 × 3 | Conv2D | 3 × 3/1/1/32 | 112 × 112 × 32 | 896 |

| 112 × 112 × 32 | MaxPooling | 2 × 2/2/0/- | 56 × 56 × 32 | 0 |

| 56 × 56 × 32 | Conv2D | 3 × 3/1/1/64 | 56 × 56 × 64 | 18,496 |

| 56 × 56 × 64 | MaxPooling | 2 × 2/2/0/- | 28 × 28 × 64 | 0 |

| 28 × 28 × 64 | Dropout (0.25) | — | 28 × 28 × 64 | 0 |

| 28 × 28 × 64 | Conv2D | 3 × 3/1/1/64 | 28 × 28 × 64 | 36,928 |

| 28 × 28 × 64 | MaxPooling | 2 × 2/2/0/- | 14 × 14 × 64 | 0 |

| 14 × 14 × 64 | Dropout (0.25) | — | 14 × 14 × 64 | 0 |

| 14 × 14 × 64 | Reshape | — | 12,544 × 1 | 0 |

| 12,544 × 1 | Conv1D | 8 × 1/8/0/4 | 1568 × 4 | 36 |

| 1568 × 4 | Flatten | — | 6272 | 0 |

| 6272 | Dropout (0.5) | — | 6272 | 0 |

| 6272 | Dense | — | 2 | 12,546 |

| Model | FC Layer Parameter Count | Overall Parameter | Percentag of FC layer |

|---|---|---|---|

| LeNet | 59 K | 62 K | 95% |

| AlexNet | 59 M | 61 M | 96% |

| VGG-16 | 123 M | 138 M | 89% |

| Model | Precision | Recall | Accuracy | Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MobileNetV2 | 0.858 | 0.850 | 0.855 | 4.3 M |

| EfficientNet-Lite | 0.855 | 0.838 | 0.848 | 4.7 M |

| SqueezeNet | 0.817 | 0.822 | 0.819 | 1.24 M |

| Efficient-D1 | 0.879 | 0.874 | 0.877 | 6.6 M |

| DERT | 0.863 | 0.888 | 0.874 | 8.5 M |

| IDD-net | 0.899 | 0.930 | 0.913 | 13.1 M |

| Ours | 0.927 | 0.950 | 0.938 | 0.7 M |

| Window Length | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kernel Number | |||||

| 1 | 0.874 | 0.828 | 0.845 | 0.846 | |

| 2 | 0.906 | 0.885 | 0.868 | 0.874 | |

| 4 | 0.918 | 0.927 | 0.917 | 0.886 | |

| 6 | 0.925 | 0.918 | 0.874 | 0.898 | |

| 8 | 0.918 | 0.908 | 0.908 | 0.876 | |

| Method | Precision | Recall | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| FC layers | 0.936 | 0.942 | 0.939 |

| GAP | 0.875 | 0.886 | 0.880 |

| 1D convolutions | 0.927 | 0.950 | 0.938 |

| Training Data | Precision | Recall | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Real-only | 0.787 | 0.810 | 0.796 |

| Real + Synthetic | 0.927 | 0.950 | 0.938 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qu, G.; Liao, J.; Liu, K.; Xu, B.; Qian, Y. Automotive Scratch Detection: A Lightweight Convolutional Network Approach Augmented by Generative Adversarial Learning. Machines 2025, 13, 1107. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121107

Qu G, Liao J, Liu K, Xu B, Qian Y. Automotive Scratch Detection: A Lightweight Convolutional Network Approach Augmented by Generative Adversarial Learning. Machines. 2025; 13(12):1107. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121107

Chicago/Turabian StyleQu, Guojie, Jiaying Liao, Kai Liu, Bin Xu, and Yuwen Qian. 2025. "Automotive Scratch Detection: A Lightweight Convolutional Network Approach Augmented by Generative Adversarial Learning" Machines 13, no. 12: 1107. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121107

APA StyleQu, G., Liao, J., Liu, K., Xu, B., & Qian, Y. (2025). Automotive Scratch Detection: A Lightweight Convolutional Network Approach Augmented by Generative Adversarial Learning. Machines, 13(12), 1107. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121107