Abstract

This research presents a cooperation strategy for a heterogeneous group of robots that comprises two Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) and one Unmanned Ground Vehicles (UGVs) to perform tasks in dynamic scenarios. This paper defines specific roles for the UAVs and UGV within the framework to address challenges like partially known terrains and dynamic obstacles. The UAVs are focused on aerial inspections and mapping, while UGV conducts ground-level inspections. In addition, the UAVs can return and land at the UGV base, in case of a low battery level, to perform hot swapping so as not to interrupt the inspection process. This research mainly emphasizes developing a robust Coverage Path Planning (CPP) algorithm that dynamically adapts paths to avoid collisions and ensure efficient coverage. The Wavefront algorithm was selected for the two-dimensional offline CPP. All robots must follow a predefined path generated by the offline CPP. The study also integrates advanced technologies like Neural Networks (NN) and Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) for adaptive path planning for both robots to enable real-time responses to dynamic obstacles. Extensive simulations using a Robot Operating System (ROS) and Gazebo platforms were conducted to validate the approach considering specific real-world situations, that is, an electrical substation, in order to demonstrate its functionality in addressing challenges in dynamic environments and advancing the field of autonomous robots.

1. Introduction

In the literature, several reports have surveyed strategies for the cooperation of heterogeneous robots [1,2]. One intriguing interaction between heterogeneous robots is a UAV landing on an Unmanned Ground Vehicle (UGV), where the UGV is in motion, requiring the UAV to adjust its velocity to reach the landing spot dynamically [3]. In Berger et al. [2], the authors also proposed a similar approach. The UAV can land and return from a UGV base to perform a “hot swapping”. Multi-robot cooperation is also used to perform Coverage Path Planning (CPP). The coordination of heterogeneous robots, including both aerial vehicles and ground-based UGVs, within the framework of CPP presents a promising approach for a wide range of applications due to the possibility of an efficient coverage of large and complex environments [4].

An important aspect to be mentioned in cooperation between robots is the fact that most of the research in the literature encompasses homogeneous multi-robot systems due to their simplicity and scalability [5,6]. The heterogeneity among robot teams enhances performance in various aspects [6]. This collaboration between heterogeneous robots introduces new challenges, particularly in task allocation, where factors such as robot characteristics (e.g., battery life and coverage area) must be carefully considered [6]. UGVs can handle substantial payloads, accommodating various sensors and actuators, albeit with limited visibility. In contrast, UAVs offer an elevated viewpoint but are constrained by limited payload capacity and flight time due to power constraints [3].

Note that integrating aerial and ground robots assign new implementations for advancing the coordination and communication between the robots to guarantee efficient cooperation. Addressing challenges concerning the optimal distribution of tasks across these varied platforms, the efficient management of energy resources, and the assurance of safe interactions in dynamic settings is extremely important. In this sense, it is essential to develop robust algorithms that can flexibly adjust the cooperation of the heterogeneous robot teams to ensure the successful implementation of the coverage path planning with real-world conditions and uncertainties.

UAVs are a promising solution applicable across various domains, including search and rescue [7,8], inspection [9], Industry 4.0 [10], and remote sensing [11], among other fields. Over the years, these robots have proven to be valuable tools for exploring complex and dynamic environments [12,13]. Their adaptability to tasks of different levels of complexity, capacity to adjust to dynamic surroundings, and agility for maneuvering make them versatile tools for different applications [14,15].

In complex and dynamic scenarios, trajectory planning is crucial, enabling UAVs to track targets during missions by following predefined global paths while navigating dynamically [16]. In dynamic settings, potential obstacles pose challenges for UAVs. That being the case, UAVs must exhibit autonomy to execute various operations and make informed decisions based on available data. Path planning, in particular, demands access to extensive environmental data to ensure credibility, safety, and efficiency [17]. UAVs face the critical challenge of determining an optimal, or nearly optimal, collision-free route while considering both the initial and target positions. This requires continuous monitoring of the vehicle during its operation. Additionally, the flight time imposes several challenges for this kind of robot.

While UAVs are limited by battery life and flight duration, UGVs typically have higher payload capacity, allowing this kind of robot to carry heavier equipment, sensors, and payloads, making them suitable for applications requiring extensive sensor arrays and can operate for longer periods, especially if equipped with efficient power sources [2]. In this sense, by integrating these two kinds of robots, UAVs, and UGVs, in an inspection process, which is the case of this research work, diverse terrains and environments can be coverage more effectively. UAVs can provide aerial overviews and reconnaissance, identifying potential obstacles or areas of interest. At the same time, UGVs can navigate complex terrain, investigate ground-level details, and interact with the environment directly if needed. Their different behavior features can improve the inspection process by acquiring environmental data from both aerial and ground-level perspectives, having a continuous inspection, overcoming the individual limitations of each robot, and enhancing overall mission effectiveness.

In an autonomous inspection process, two motion planning strategies based on sensory information acquired from the environment exist: global and local path planning [18]. The literature presents several solutions for these strategies [19,20]. Global path planning involves generating a trajectory from the robot’s current position to the goal while considering the entire environment, whereas local path planning focuses on navigating around obstacles.

Motion planning algorithms are crucial for guiding autonomous robots as they navigate through complex and multi-dimensional environments [21,22]. Diverse approaches in the literature rely on heuristic methods for motion planning [23]. A drawback of these approaches is that they often encounter challenges when applied to high-dimensional settings, which are most common in real-world applications. In response to these challenges, researchers have explored alternative approaches, including using Neural Networks (NN) as online path planners, as demonstrated in Sung et al.’s research [24].

The training dataset employed for this purpose incorporates the designated paths the robots intend to navigate. NNs offer flexibility and real-time adaptability. This makes then suitable for various applications and dynamic, complex environments. By learning from the training data, NN-based path planners can effectively navigate through environments with varying obstacles and terrain, adjusting their trajectories in real time based on the sensory inputs. Integrating NN-based path-planning techniques into autonomous robot systems can enhance their adaptability and robustness, enabling them to navigate challenging environments more effectively. The NN employed is a promising solution for improving the autonomy and performance of UGVs and UAVs in real-world applications, such as surveillance, exploration, and inspection tasks.

Adaptability becomes an important feature in dynamic environments where sensors may detect unanticipated obstacles. Path planning systems must swiftly respond to these detected obstacles, recalibrating the assigned path to ensure avoidance while progressing toward the final destination [25]. For example, Zhang et al. [26] introduced a solution that employs the A* algorithm for global path planning in partially known maps, followed by using the Q-learning method for local path planning to navigate around locally detected obstacles.

The inspection process is performed in an electrical substation. This environment was chosen due to its critical infrastructure components. Electrical substations require regular inspections and maintenance to ensure operational efficiency and safety. This is a complex scenario for the robots because they can encounter operators in the field as well as cable trays, piping, conduits, and other structural supports that can make their navigation during inspections difficult.

In this work, the authors propose combining online adaptive and coverage path planning algorithms. By integrating DQN into our cooperative robotics framework, we aim to address the challenges associated with dynamic environments, including unanticipated obstacles and changing terrain conditions. The motivation behind this integration is to enable the robotic inspection system to navigate efficiently through the electrical substation, covering all necessary areas while avoiding collisions and hazards. The CPP algorithm generates feasible paths to coverage all inspected area. At the same time, the combination of RRT and DRL techniques enables the robots to dynamically adjust their paths based on real-time sensor data, optimizing coverage and ensuring the inspection of the whole facility.

1.1. Main Contributions

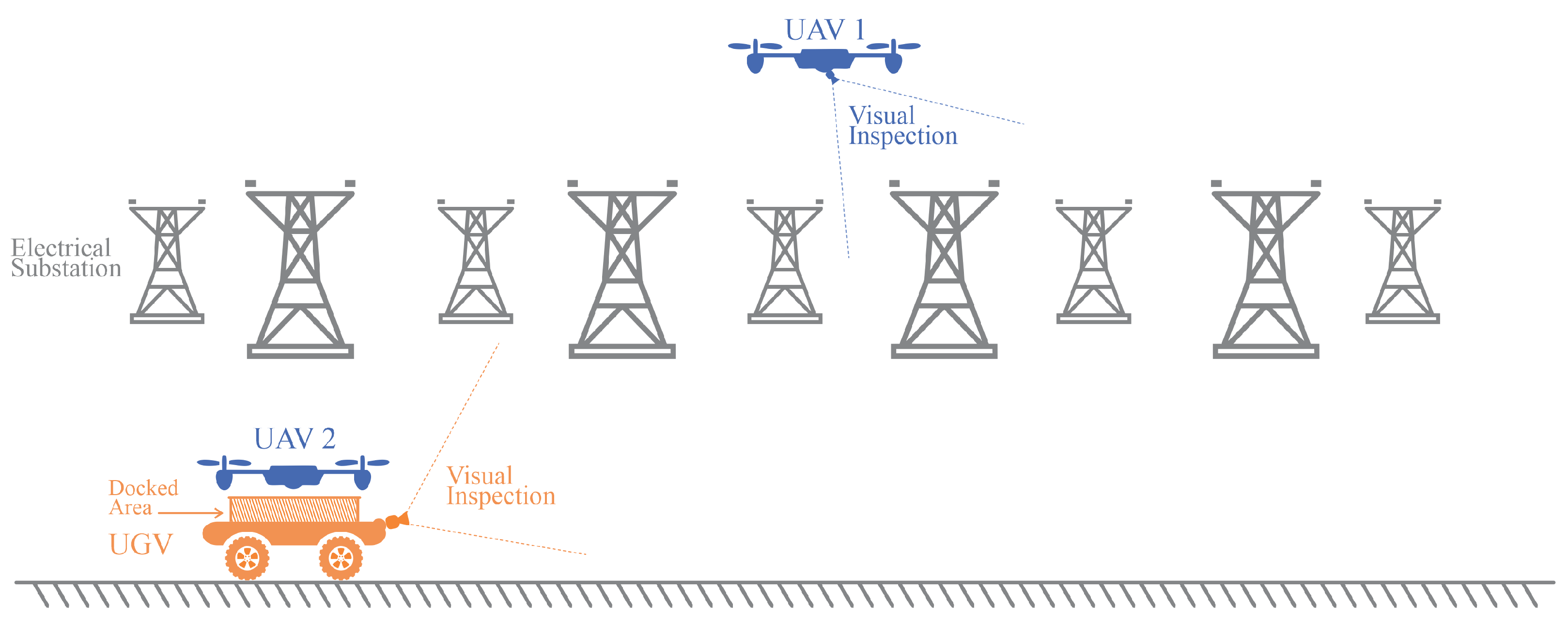

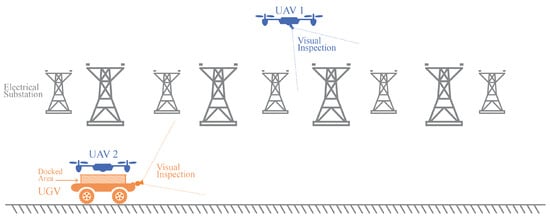

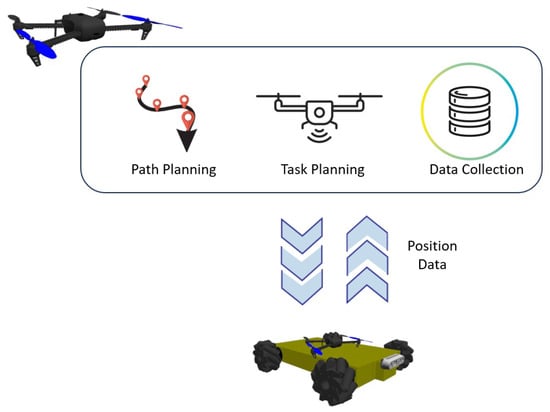

This work introduces a novel cooperation strategy for a heterogeneous group of robots, specifically two UAVs and one UGV. The robots operate to perform an inspection mission. The strategy addresses the challenges of partially known terrains and potential dynamic obstacles, delineating the distinct roles of the UAVs and the UGV within the proposed cooperation framework. The UAVs are tasked with conducting aerial inspections, providing continuous updates to the environmental map, and swiftly navigating complex environments from an elevated high. Simultaneously, the UGV is responsible for ground-level inspections, contributing to map updates, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

General idea.

Furthermore, the UGV can serve as a landing point for the UAVs to perform “hot” battery swapping, as demonstrated in the literature [27,28]. The main idea is to ensure uninterrupted data collection without constant human intervention, enhancing the overall efficiency of the inspection operation.

This work also emphasizes the development of an architecture that combines online adaptive and coverage path planning. The CPP algorithm is based on the Wavefront algorithm. All robots must follow the predefined route given by the offline CPP. However, the online adaptive methodology dynamically adjusts the path in real-time. This part of the methodology combines Rapidly Exploring Random Trees (RRT) and Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) techniques, similar to Castro et al. [12]. Different from this mentioned work, the neural network model and the filters associated with the outputs are the same for the UAVs and UGV. Only the input vector assumes other values since the agent’s sensors, the pose, and path next node can differ for each robot. The main contributions of this work can be summarized as follows.

- Introducing a cooperation strategy for a group of heterogeneous robots operating in dynamic environments with partial knowledge of the area and with potential dynamic obstacles;

- Proposing an effective CPP strategy considering the minimization of travel distance, reducing mission time, and considering constraints like flying time of UAVs;

- Assessing the proposed approach by performing tests in a realistic simulation environment as a proof of concept.

This work does not focus on the details of implementing the image processing algorithm for the inspection process and implementing the “hot-swapping” battery procedure. These aspects fall outside the scope of this research. Extensive simulations are conducted using the Robot Operating System (ROS) and the Gazebo platform to assess the efficacy of the proposed methodology.

1.2. Organization

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2.1 provides an overview of related works focusing on cooperation between robots and coverage path planning. Section 3 presents an overview of the proposed architecture for the partially unknown environment and its mathematical foundations. Section 4 validates and assesses the proposed strategy. Finally, the concluding remarks and ideas for future work are given in Section 5.

2. Related Works

2.1. Cooperative Heterogeneous Robots

The cooperation between robots is designed to maximize local objectives based on each robot’s behavior and strategies. In the case of formations, the robots typically entail cooperative interactions, where the agent states are interlinked based on objectives like energy efficiency (similar to birds flocking in an aerodynamically optimized V-formation [29]). Concerning swarms, they are comprised of groups of similar agents exhibiting emergent behavior resulting from local interactions between the agents [30].

Homogeneous robots, i.e., identical or similar robots, share the same functionalities. Their collaboration enables them to perform tasks by coordinating the robots’ actions to achieve specific objectives [5]. Compared to heterogeneous robots, this kind of collaboration may lack the ability to solve tasks in complex scenarios, as demonstrated in [2]. In this sense, the choice between homogeneous and heterogeneous groups of robots is based on the application’s requirements.

Heterogeneous robots have diverse capabilities and functionalities that allow them to perform tasks in different applications. The collaboration of different kinds of robots introduces challenges for task allocation, considering factors like battery life and coverage area alongside novel applications and concepts. The great advantage of using UGVs is that they can carry substantial payloads. This enables them to carry a variety of sensors and actuators and possible interaction with the environment. This kind of robot suffers from a limited perspective due to its low positioning. The use of UAVs offers a high viewpoint but with constraints in payload capacity and flight duration due to power efficiency [3].

In this sense, several challenges are still being studied regarding the collaboration of a heterogeneous group of robots. For instance, Shi et al. [6] tackled the synchronizing tasks between diverse robots by introducing a partitioning approach for heterogeneous environments that accounts for the cost space associated with their varying capabilities. Chen et al. [31] showed a two-stage path-planning approach using a modified ant colony optimization and genetic algorithm. In their work, the UGV’s path was restricted to the road network, and the UAV’s and UGV’s paths were optimized simultaneously to get the optimized paths.

Another significant contribution arose from the work of Kim et al. [32], where the authors proposed an optimal path strategy for navigating 3D terrain maps using UAV sensors to ensure precise task execution. Arbanas et al. [33] designed a UAV capable of picking up and placing packages into a mobile robot to improve the process of autonomous transportation. In Stentz et al. [34], a UAV accompanies the UGV to detect obstacles such as holes or steep slopes.

Several works in the literature have proposed solutions to deal with heterogeneous robots in different scenarios. Berger et al. [2] suggested an architecture for agriculture cooperation between UAV and UGV for insect trap inspection, where the aircraft can land on the UGV for charging purposes. Zhao et al. [35] proposed an approach for elderly care based on seven heterogeneous nursing robots and a multi-robot task allocation algorithm considering execution time and energy consumption. Quenzel et al. [36] showed the application of a team of UAVs cooperating with a UGV for autonomous fire fighting.

Regarding real-world tests, the work of Langerwisch et al. [37] showed cooperation in a large field experiment with six heterogeneous UGVs and UAVs to perform reconnaissance and surveillance without constant observation by a human operator. The authors of Michael et al. [38] worked with controlling the formation of the ground robots performed by a UAV as a flying eye.

2.2. Coverage Path Planning

In recent decades, the collaboration in multi-robot systems in practical applications has gained significant attention. This collaboration poses the challenge of Multi-Robot Task Allocation (MRTA), where the objective is to coordinate numerous robots to complete specific tasks under defined constraints [39]. These tasks encompass various domains, ranging from land-based robots like Automated Guided Vehicles (AGVs) and UGVs to air-based robots, including planes, blimps, and UAVs. Water-based robots, exemplified by Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) and Unmanned Surface Vehicles (USVs), constitute the third category. For the scope of this study, the focus will be on the collaboration between one UGV and two UAVs in an inspection task.

Inspection tasks using UAVs should guarantee flight time optimization due to battery time restrictions, the best trajectory to cover a determined area, and data gathering for further processing. CPP devises a robot’s path to cover an accessible area within a predetermined environment. This methodology must be efficient and provide sufficient information for the necessary analysis. An inspection application that applies CPP can be seen at Song and Arshad [40]. The authors perform an underwater inspection using AUV. In Kim et al. [41], the authors inspect a mining area using a two-wheeled robot.

The algorithms employed for CPP need to ensure that the robot covers all accessible areas. Commonly used techniques include heuristic methods, graph-based algorithms, artificial intelligence algorithms, and metaheuristic approaches. These algorithms range from traditional methods like Dijkstra’s algorithm [42], [43] search to more advanced techniques such as genetic algorithms [44], particle swarm optimization (PSO) [45], and neural networks [13]. Tan et al. [46] have an interesting review of coverage path planning in robotics.

Another CPP challenge is managing uncertainty regarding the robot’s position and dynamic surroundings. This uncertainty implies that the robot’s location might abruptly change due to external forces or calculation errors. The kidnapped robot problem is a standard scenario used for assessment, where the robot’s position is altered during its movement, requiring adjustment in the path planning process [13].

Not all path-planning methods can effectively address this challenge and identify feasible routes. Neural networks offer an additional advantage by being capable of handling kidnapped robot problems and moving targets. An interesting work based on Deep Neural Network (DNN) to address high-dimensional problems was proposed by Qureshi et al. [47]. Their architecture consists of an encoder network responsible for learning to encode a point cloud of obstacles into a latent space and a planning network. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have been employed to analyze camera images and generate collision-free paths in unknown dynamic environments [48]. As demonstrated in Cui et al. [49], reinforcement learning techniques have outperformed traditional Q-learning-based algorithms, leading to superior results in path planning for various applications.

Table 1 gives an overview of the characteristics of the mentioned works to compare them with the proposed methodology. Note that this work addresses the cooperation between heterogeneous robots (i.e., two UAVs and one UGV) in a dynamic environment partially mapped with potential obstacles. Each robot operates based on its feature behavior and functionality. The UAV gathers aerial information, and the UGV performs ground-level inspection. Similar to the proposition of [2], the UGV is a reference landing point for the UAV when the battery is low to perform “hot swapping”. The main advantage of this proposition is the uninterrupted data collection. That is, when one of the UAVs has a low battery and requires hot swapping, the other one continues the inspection process.

Table 1.

Related works.

As can be seen, different from the mentioned works, which are focused on aspects such as optimal path strategy, neural network-based motion planning, or the coordination of homogeneous robots, our proposed approach introduces a strategy to ensure uninterrupted data collection during an inspection process. The proposition also tackles the challenge of dynamic environments since the robot can encounter operators in the field and structural supports during the navigation.

3. Proposed Methodology

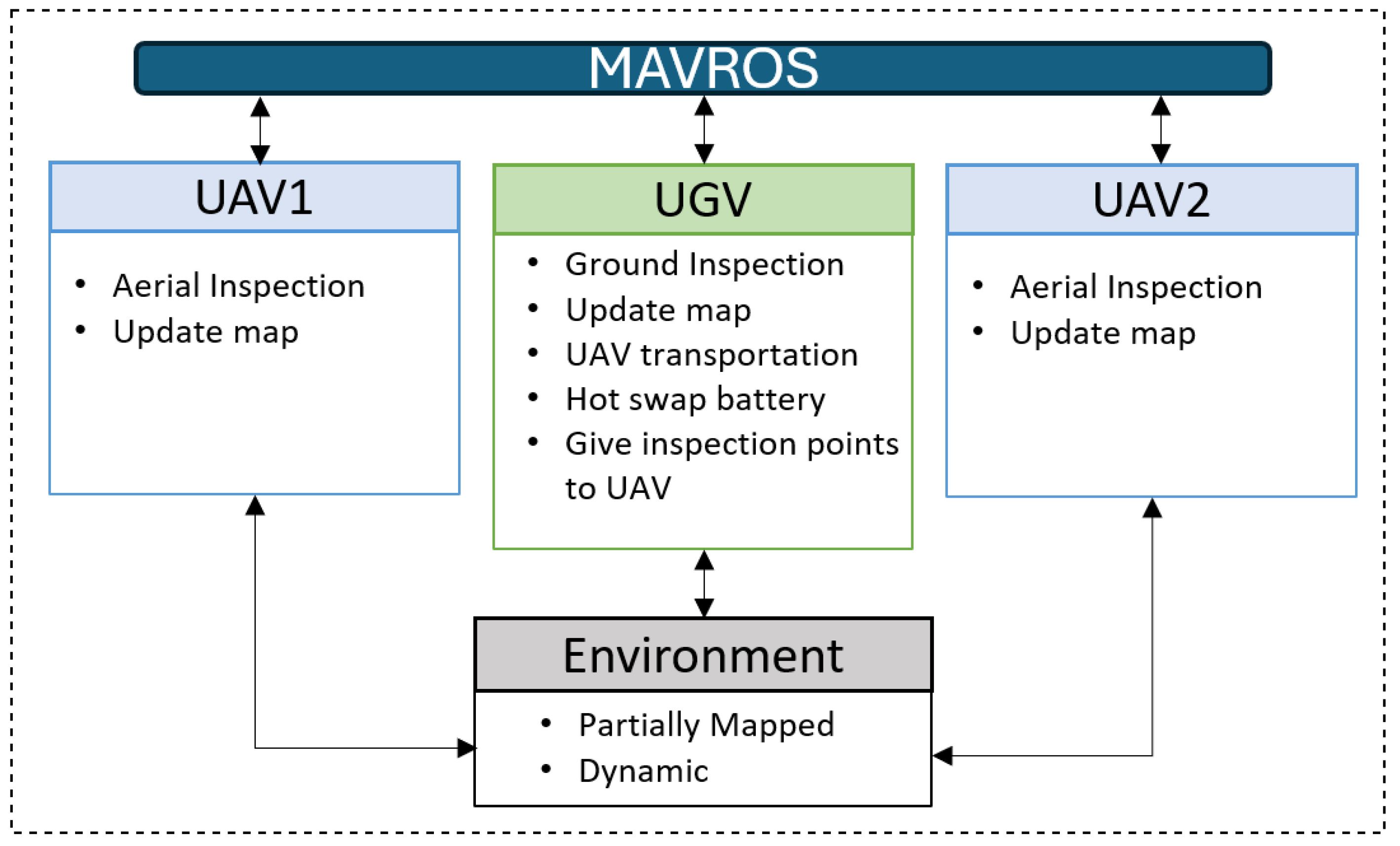

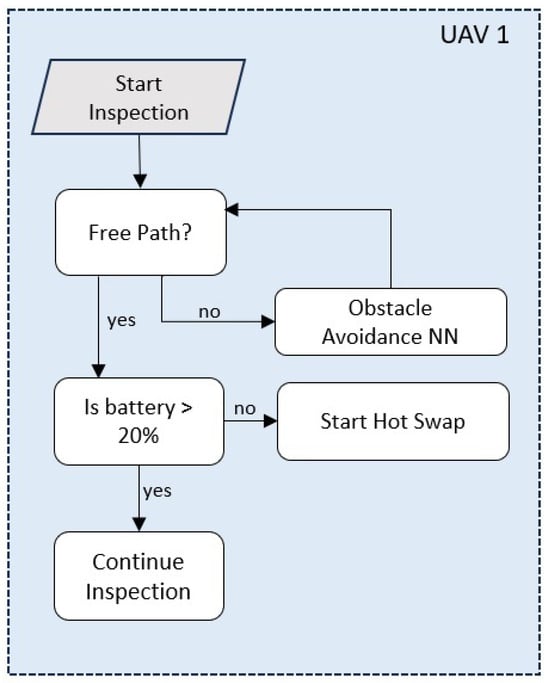

Figure 2 provides an overview of the proposed cooperation strategy. The UAVs take on the role of conducting aerial inspections and continuously updating the environment map. They can swiftly maneuver and gather information from an elevated perspective. Simultaneously, the UGV is responsible for ground-level inspections, contributing to map updates, and demonstrating a unique feature: the ability to transport a UAV on its top. This dual functionality enhances the versatility of the UGV, allowing it to operate independently and in tandem with the UAV. An interesting aspect of this cooperation is the concept of “hot swapping.” In cases where the UAV’s battery level becomes low during its aerial mission, it can seamlessly land on the UGV for a swift battery replacement or recharge. When this happens, the other UAV continues the mission. This feature ensures the UAV’s continuous operation and minimizes downtime, making the entire system more efficient and adaptable to the dynamic demands of the environment. Note that it is considered that the robots share information about their positions and progress and detect obstacles to avoid conflicts, ensuring seamless cooperation.

Figure 2.

Overview of the proposed cooperation strategy.

3.1. Problem Description

Let the world space of states be defined as and , , and closed subsets of , hence and described as:

- The obstacles space of states.

- The desired area for UAVs to cover.

- The desired area for UGVs to cover.

- The UAV1 space of states.

- The UAV2 space of states.

- The UGV space of states.

Where:

- are the respective agent’s pose.

- is the sensors readings vector.

- is the agent’s battery percentage status where .

The desired coverage areas described by and are defined by fixing the z parameter and then subtracting and . Equation (1) shows that relation, where for the UAV, the z parameter will be the altitude for inspection, and for the UGV, z is set to 0.

The problem can be described as trying to find the best path , in terms of overlapping and maneuvering that links all the states in the substates and with their respective agent’s home position, constrained by the status battery (), the pre-defined inspection altitude and the world bounders . Equation (2) describes the paths and the constraints for UAVs and UGV, where and will be our cost function and the optimization of them is the developed architecture proposed in this work.

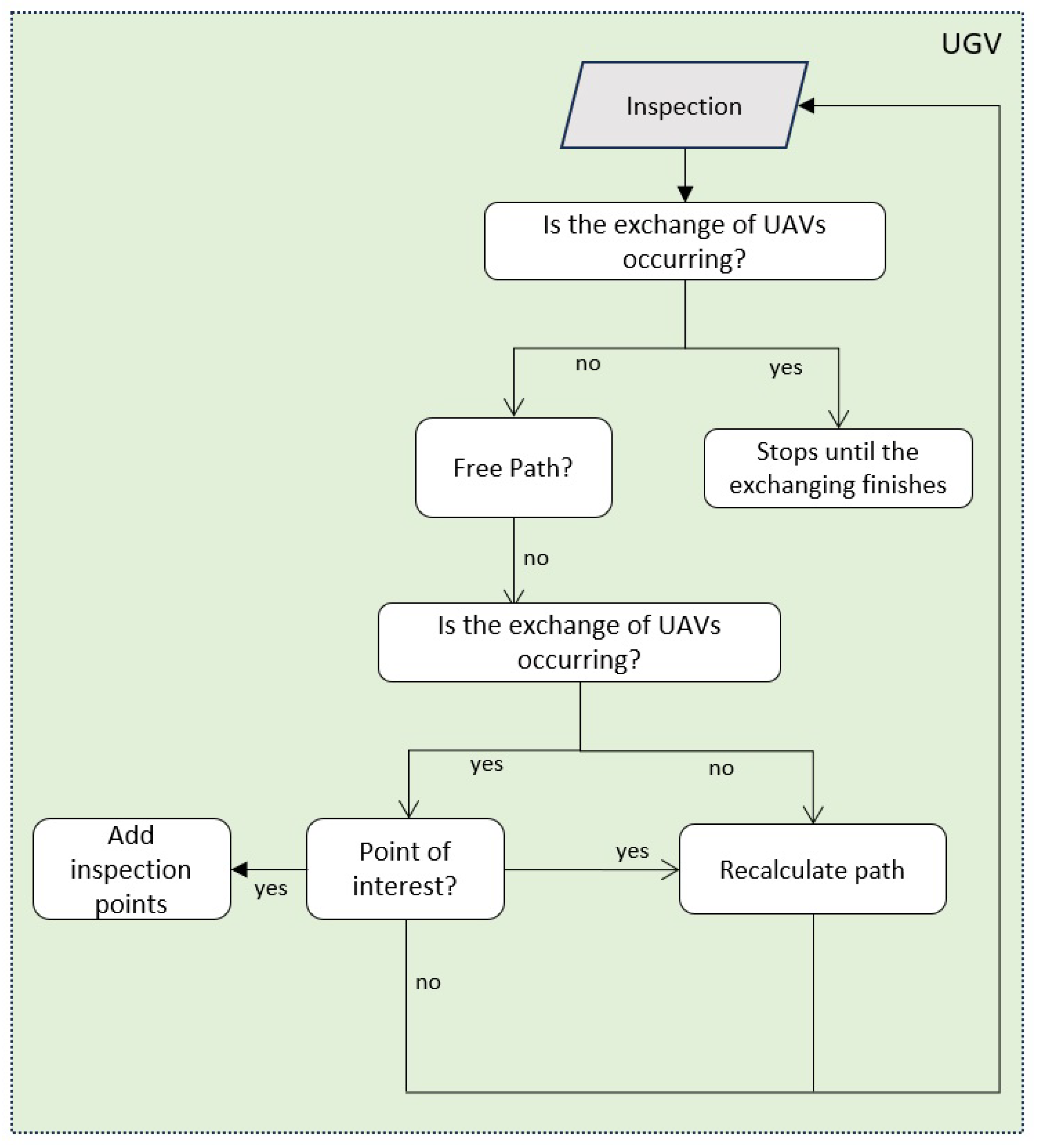

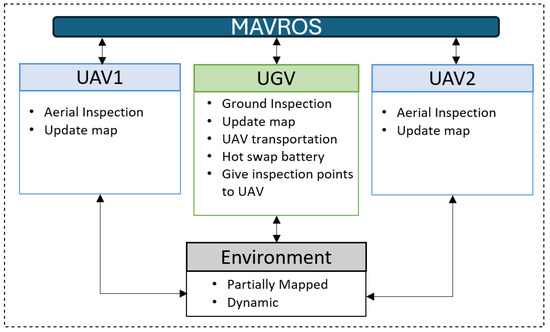

3.2. Ground Inspection

In the context of coverage path planning for heterogeneous robot teams, it is essential to establish a clear mission initiation protocol. Typically, the UGV takes the lead by initiating the mission. As it sets out on its path, the UGV’s first task is to ensure the path ahead is clear and free of obstacles. If the UGV is not currently engaged in hot swapping (i.e., the seamless battery replacement or recharging mechanism), it proceeds with the mission. This mission involves systematically navigating the environment, collecting data, and contributing to the coverage inspection task. This approach reflects the coordinated workflow where the UGV assumes the initial responsibility, examines the path’s feasibility, and, when conditions permit, initiates the mission. Systematic coordination and path verification are essential to ensuring successful and efficient coverage path planning in dynamic environments. Figure 3 summarizes this process.

Figure 3.

UGV mission initiation and verification.

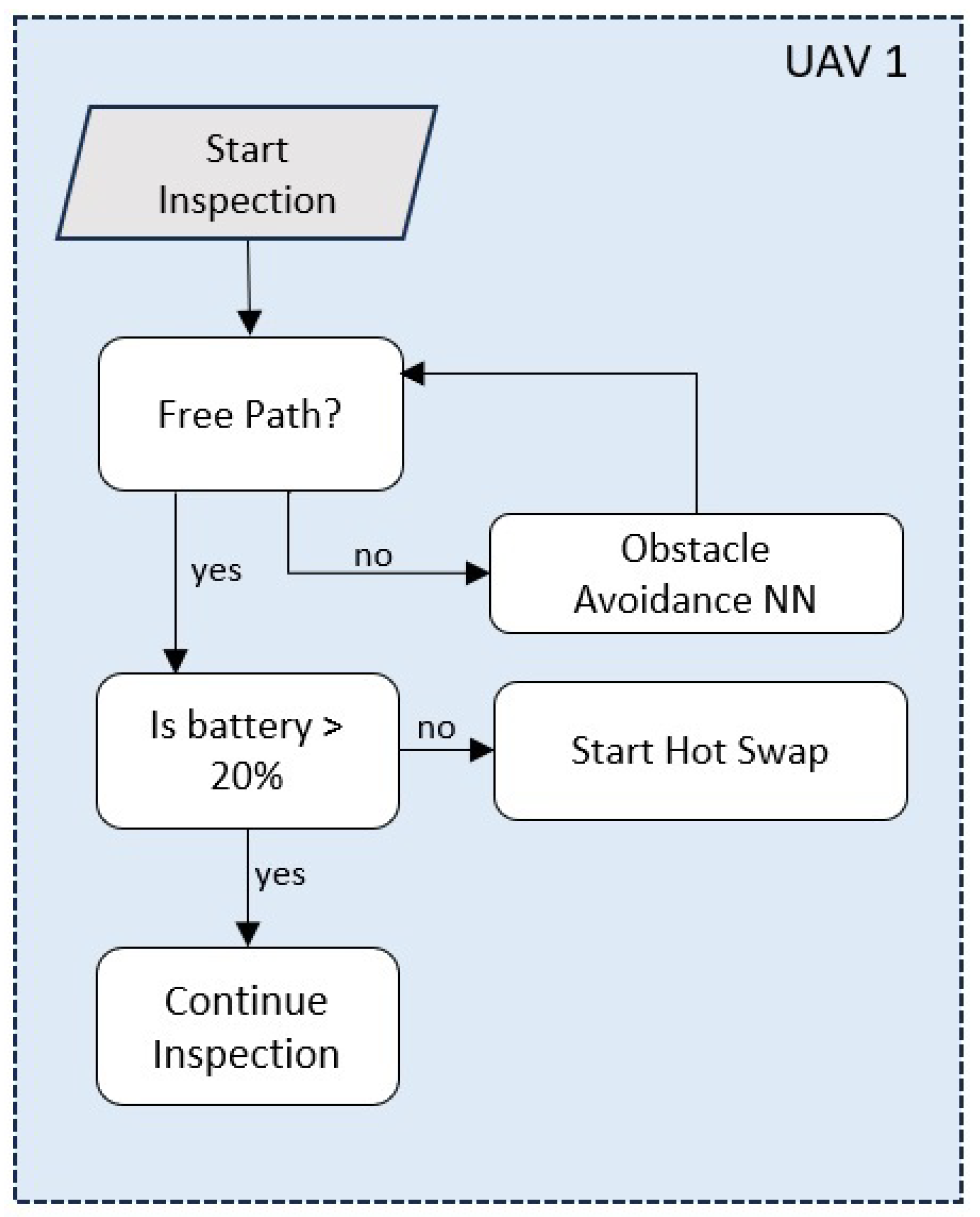

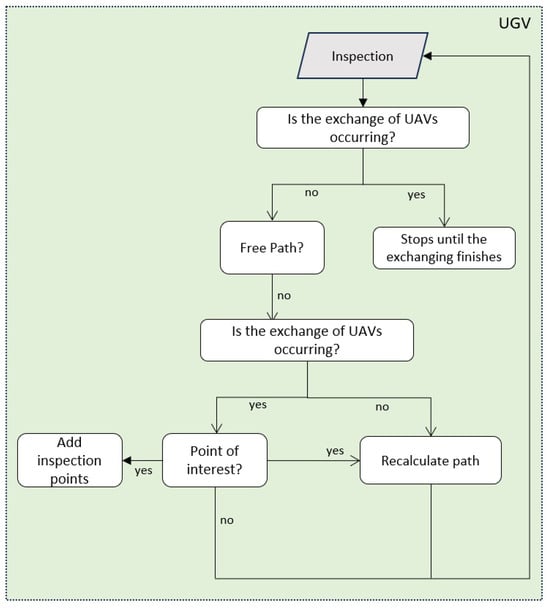

3.3. Aerial Inspection

In this specific scenario, as already mentioned, the multi-robot collaboration involves a team of two UAVs and one UGV. The UGV initiates the path assessment and mission to provide the conditions for the UAVs. Additionally, it assumes the responsibility of data collection and updating the map. Furthermore, if one of the UAVs experiences a low battery, the UGV facilitates the hot-swapping process.

Both UAVs are primarily tasked with aerial inspections. However, their operations must be carefully orchestrated to ensure coordination and prevent redundant visits to the same points of interest (PoI). It is worth noting that if the UGV encounters a PoI during its ground-level mission, it can request the UAV currently on patrol to adjust its routine and investigate the identified PoI. This collaborative approach ensures efficient coverage and thorough inspection of the target area. Figure 4 illustrates the routine of the UAV 1. Note that during data collection in the predefined path generated by the CPP algorithm, the UAV must check the free path to navigate and its battery status. Note that both UAVs present the same routine when performing inspection.

Figure 4.

Routine of UAV 1.

Figure 5 shows the position information exchanged between the aircraft during a mission and the ground base unit. The UAV must periodically transmit its current position coordinates to the UGV to allow the ground vehicle to maintain awareness of the UAV’s location in real time. Simultaneously, the UGV relays its position information to the UAV for mutual situational awareness. This bidirectional exchange of position information enables the UGV to accurately track the UAV’s movements and adjust its own path or mission objectives accordingly. For instance, if the UGV identifies a PoI during its ground-level inspection, it can request an aerial inspection in the same location.

Figure 5.

Information exchanging between the UAV during a mission and the UGV.

3.4. Coverage Path Planning Algorithm

The CPP algorithm was selected by considering scalability, computational cost, and feasibility for handling automated inspections in a substation. Both UAVs and UGV must follow a predefined path generated by the offline CPP. This path is then dynamically adjusted in real-time using a sensor-based machine learning technique. The authors have chosen to implement the Wavefront algorithm, discussed in [50], for the two-dimensional offline CPP.

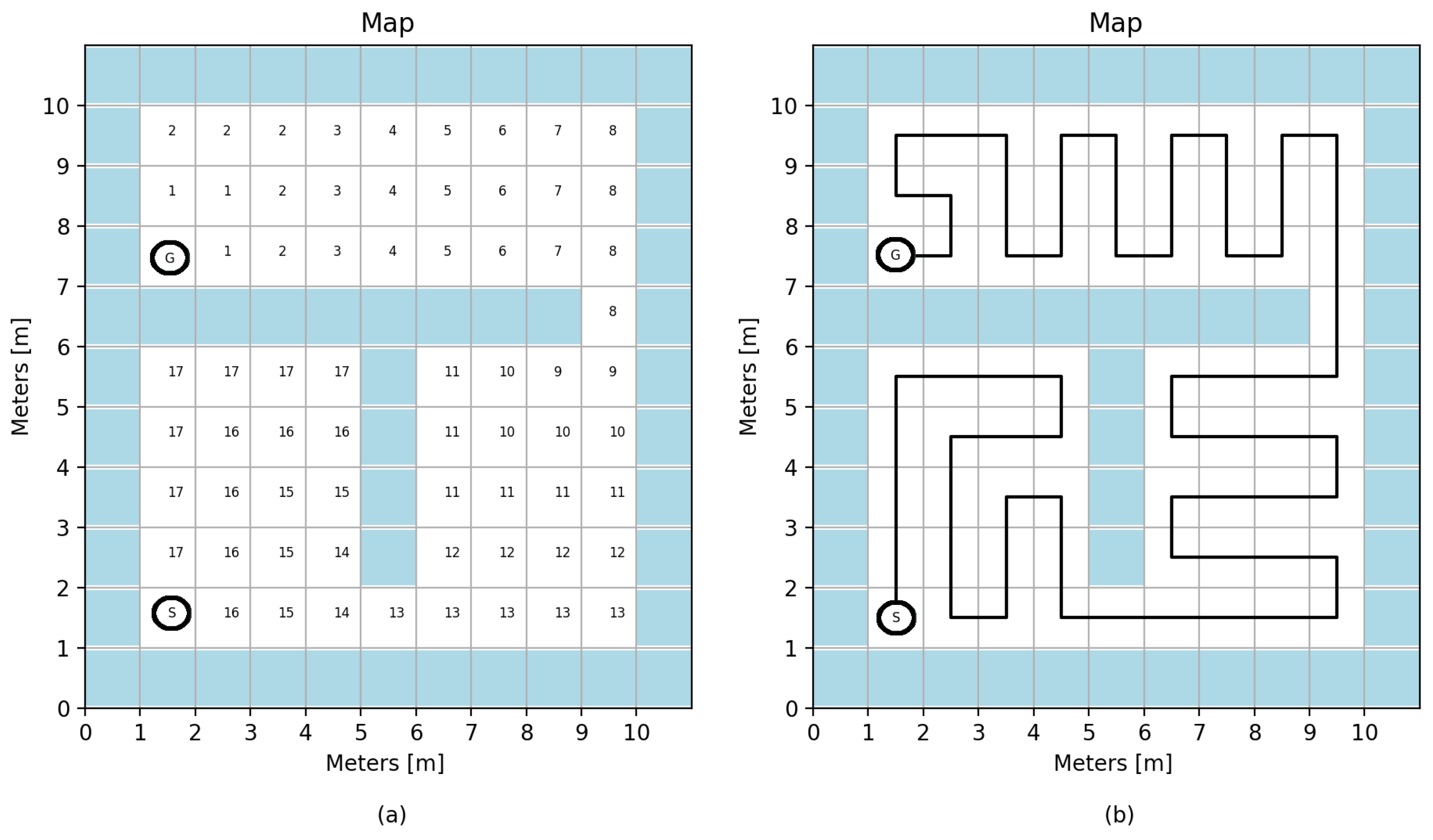

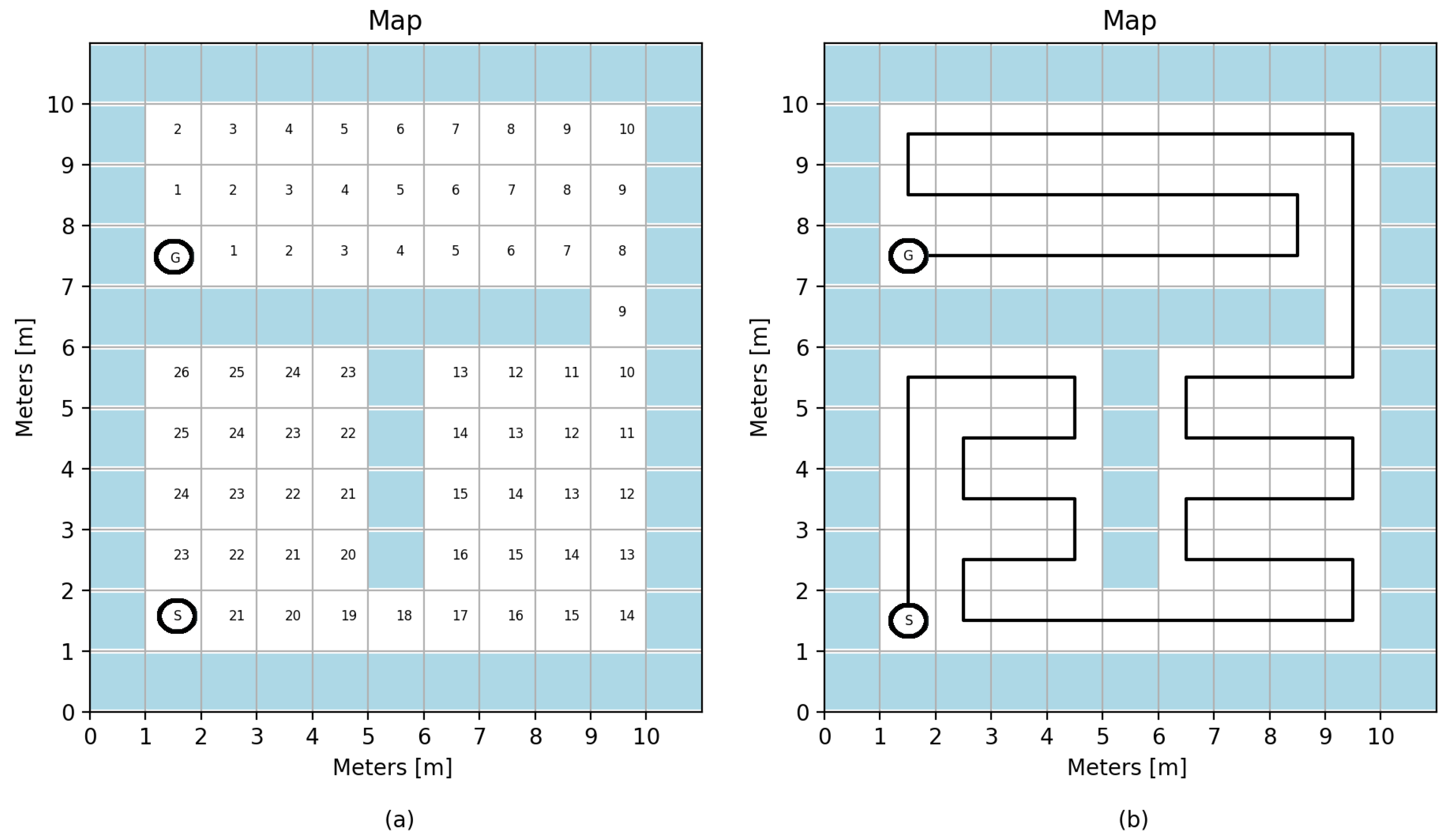

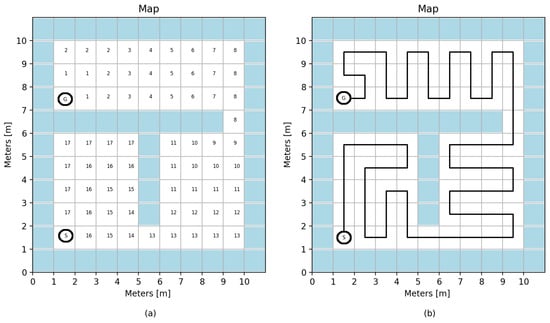

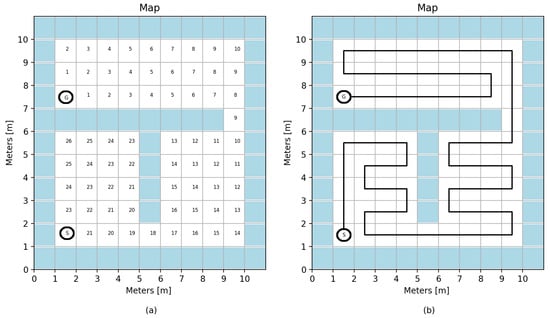

The Wavefront algorithm is a grid-based approach that propagates a wave from a target point throughout the map, applying a cost function to each grid. This cost function, which can be a distance transform as described in Jarvis et al. [51], has the drawback of producing a path with many curves, posing challenges for odometry estimation in robot implementation. They introduced a new variable to the cost function to address this issue: the variable . Figure 6 demonstrates an implementation of the algorithm using only a distance transform, highlighting the path’s curvature. It shows a grid-based map with several cells representing different terrain or obstacles. The starting point is labeled as “S”, and the goal point is labeled as “G”. Figure 6a presents the wave propagation from the goal point throughout the map. This illustrates the distance process transform propagation, where each cell is assigned a cost based on its distance from the goal. Figure 6b is the optimal result path acquired from the wave propagation.

Figure 6.

Wavefront algorithm example for the random map, where S is the starting point, and G is the goal. (a) Distance transform propagation wave from the goal. (b) Path acquired from the wave.

Zelinsky [50] applied a path transform approach, wherein instead of propagating the distance from the goal, the algorithm propagates a new cost function. This cost function takes advantage of a weighted sum between the distance and a discomfort factor associated with moving near obstacles. The path transform cost function for each cell is described in Equation (3), where the discomfort factor can be adjusted to influence the path’s adventurous or conservative nature.

- : Cost function;

- : Manhattan distance from the cell to the goal;

- N: Number of objects;

- : Discount factor;

- : Obstacle distance.

Figure 7 illustrates the path generated when applying the path transform cost function to the same map shown in Figure 6. This strategy aims to shape the environment, resulting in a path with fewer turns and more straight segments.

Figure 7.

Wavefront algorithm example for the random map, where S is the starting point, and G is the goal. (a) Path transforms propagation wave from the goal. (b) Path acquired from the wave.

Figure 7a gives the path transforms wave propagation originating from the goal point throughout the map. From Figure 7b, it is possible to verify that the path obtained through this modified approach tends to exhibit fewer curves and more straight segments. This is achieved by shaping the environment in a manner that encourages smoother trajectories, which has the potential to simplify navigation and reduce computational complexities.

3.5. Deep Q-Network

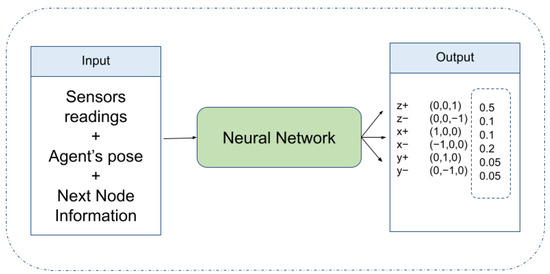

DRL is a fusion of deep and reinforcement learning algorithms. It combines the robust perceptual problem-solving capabilities of deep learning algorithms with the adaptive learning outcomes characteristic of reinforcement learning algorithms. Q-learning is a method inside the DRL family that returns the optimal solution based on a Q-value table. This algorithm encounters scalability issues when dealing with large state spaces in real-world applications. In response to this challenge, the Deep Q-Network (DQN) algorithm emerges as a promising method to address this issue. It adeptly addresses scalability concerns by integrating the Q-learning algorithm with an empirical playback mechanism, generating a target Q value by applying a convolutional neural network [52].

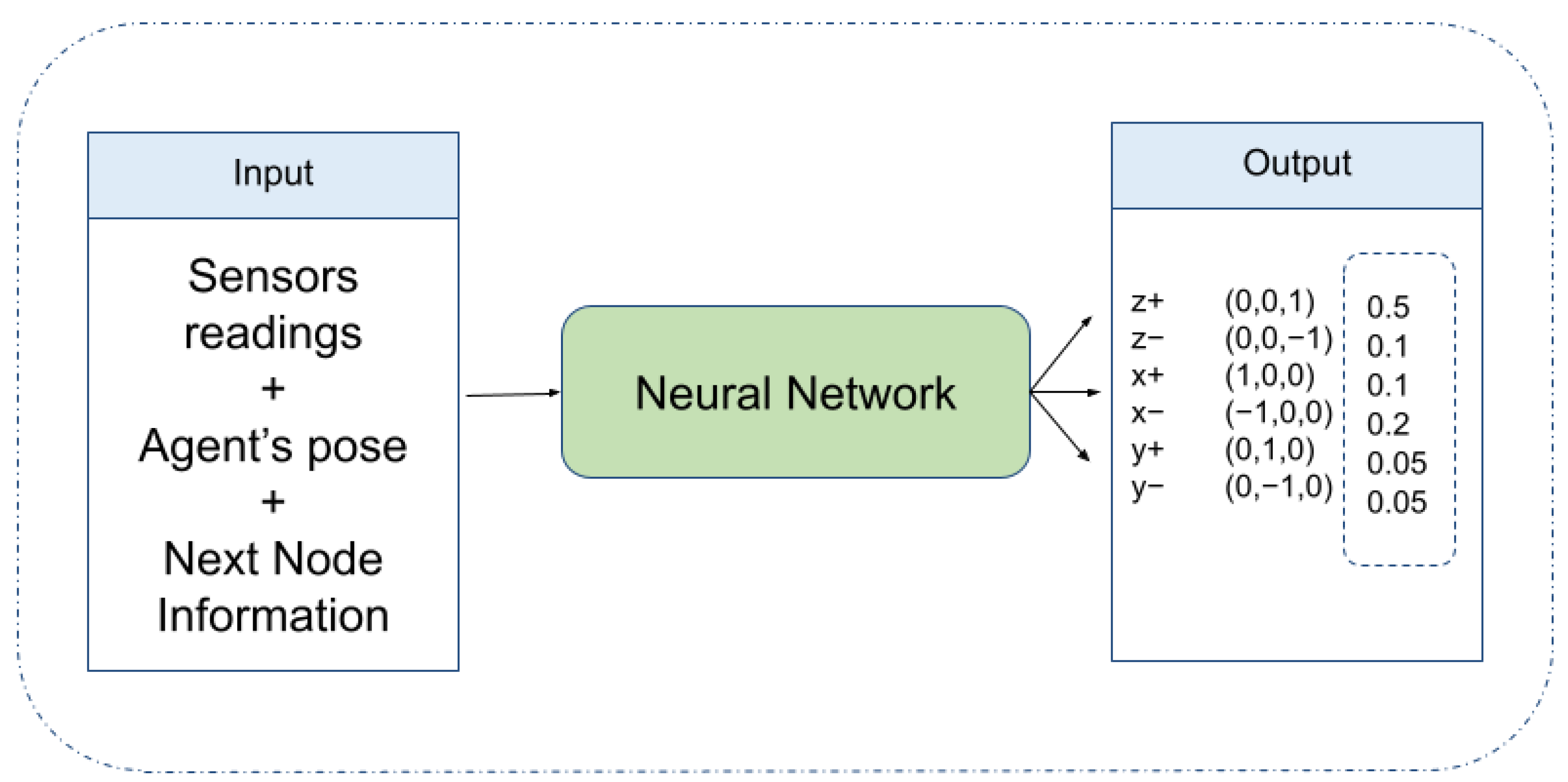

In previous work [12], the authors have extended the DRL technique to solve complex tasks such as path planning and obstacle avoidance. An adaptive path planning algorithm that combines classic path planning algorithms and DQN methods was developed. In this work, the authors extrapolated that concept and applied the same algorithm as a local optimal obstacle avoidance for all the agents within our heterogeneous robot team. The integration of DQN allows the robots to dynamically adjust their paths and navigate around obstacles encountered during their missions, ensuring safe and efficient operation in dynamic environments. The DQN topology described in [12] comprises a fully connected neural network with three layers: one for input, one hidden layer, and the last for outputting the results. Table 2 shows the number of neurons and the structure of the model. The model was extensively trained into two parts, one using an ambient developed in Python 3.8 and the other on software to simulate gravity, wind, and robotic kinematics. The simulated agent was put in these simulation environments and tried to survive objects in collision routes to it for as long as possible. It receives positive rewards if the decision leads the agent to the direction pointed as a target, and a negative reward is given if it collides, resetting the simulation and starting the next training event.

Table 2.

Neural network model description.

The input of the model is a subset of the already-discussed (Section 3.1) agent’s space of states () plus the information about the next path step, given by and described as . Equation (4) shows the relation of the neural network input and the agent’s space of states.

The output layer returns a distributed probability that indicates the direction where the agent should move. Figure 8 compiles the information about the input and output of the model.

Figure 8.

Representation of the DQN input and output variables.

To choose the output, the authors decided to apply two filters. The first uses sensor information and forces output probability to be equal to zero for occupied directions. The second one is to sample the output based on the likelihood. Let the neural network function be described as and filter one and two by and , respectively; the final output can be written as Equation (5).

The neural network model and the filters are the same for the UAVs and UGVs; only the input vector assumes other values since the agent’s sensors, the pose, and the path of the next node can be different for each robot. The neural network function is only evoked when the determined path is not empty, in other words, when . The agent’s path returns to the already calculated after five network events or when .

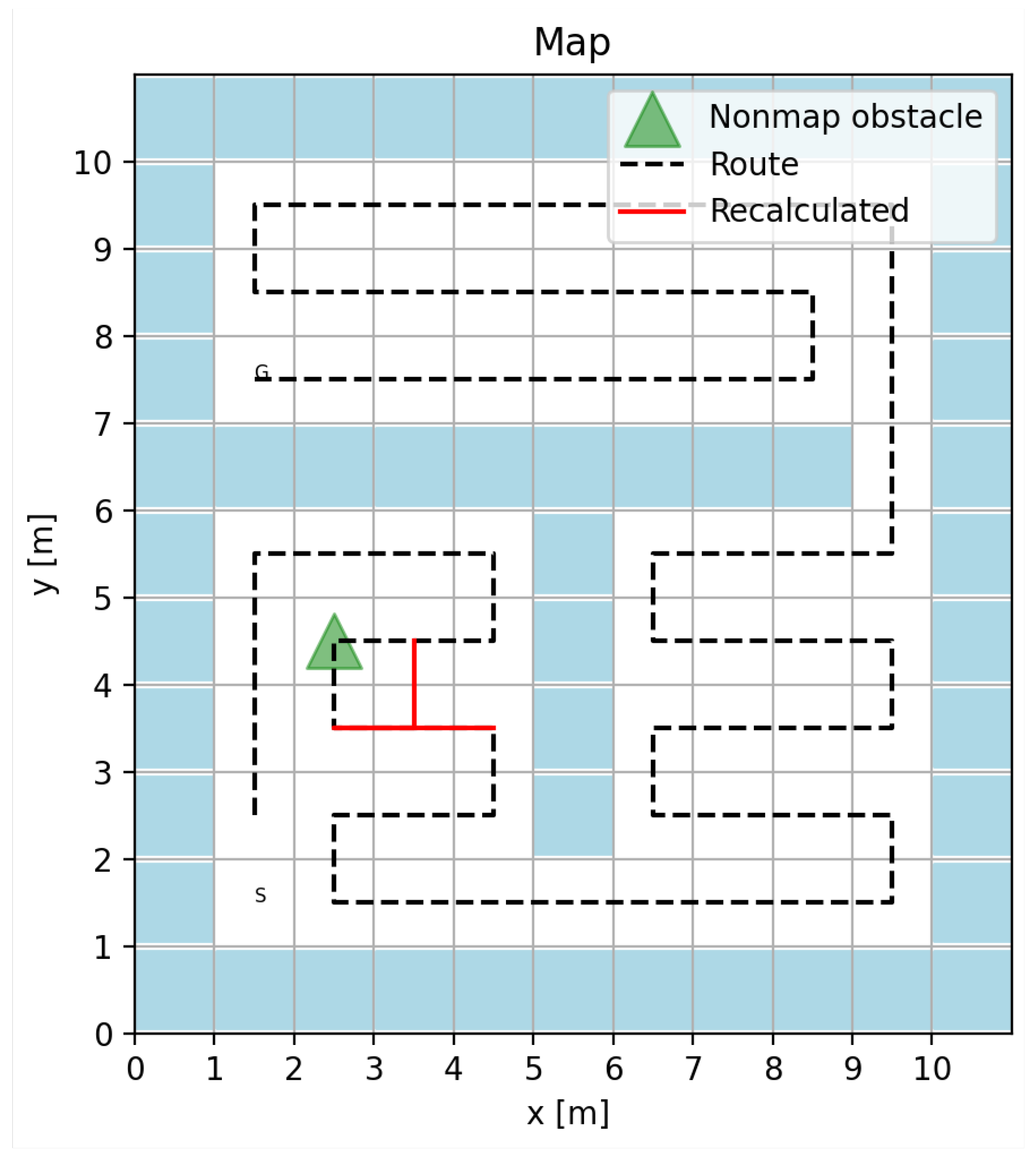

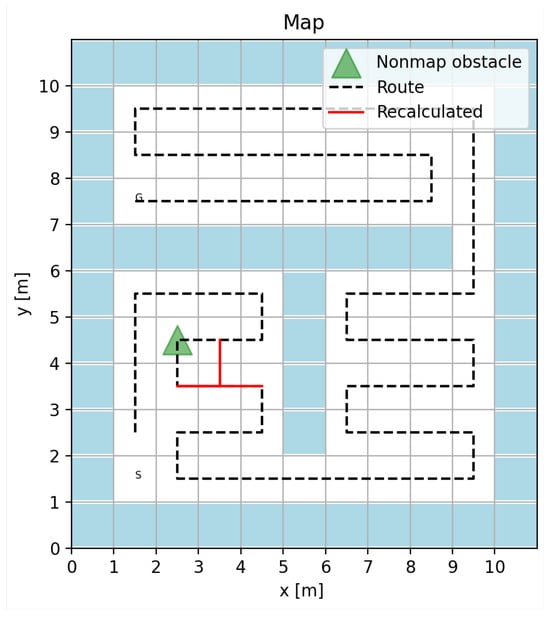

Figure 9 shows an example of a coverage path planning mission where the UGV faces an unmapped obstacle and recalculates the route. In this figure, the green triangle represents the unmapped obstacle, and the red line represents the recalculated route.

Figure 9.

Recalculating a new route (i.e., red line) for the UGV due to an unmapped obstacle.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Hardware Description

The simulations were conducted on a notebook with 8GB of RAM and powered by a 2.7 GHz Corei5-5200 processor. The chosen operating system distribution was a 64-bit Ubuntu 18.04 Bionic, complemented by the lightweight LXDE desktop environment. All algorithms were coded using Python 3.10. It is possible to access all the source code and relevant information on the following GitHub repository: https://github.com/gelardrc/mixedmission.git (last accessed on 2 January 2024).

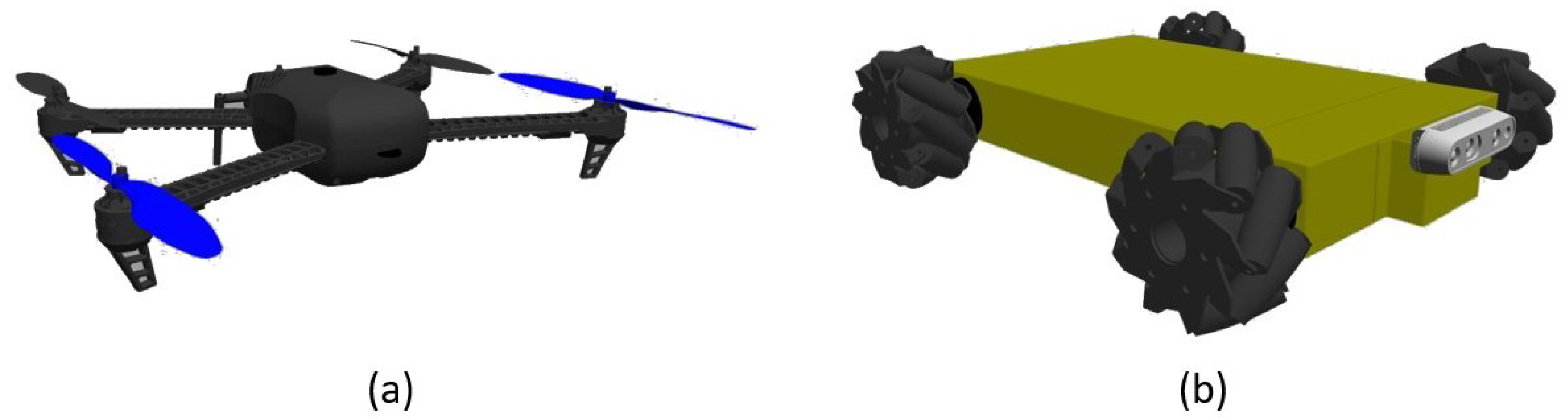

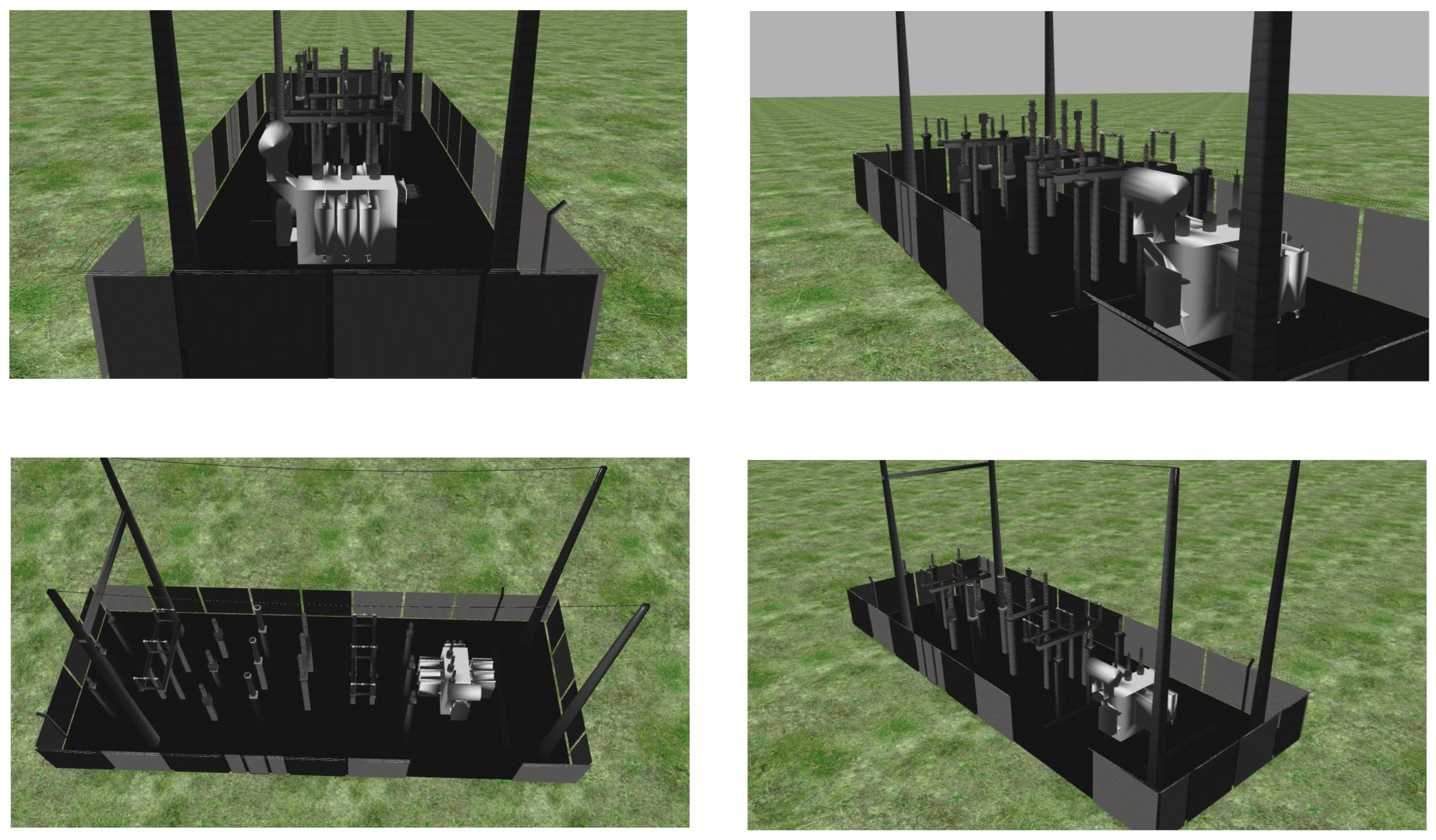

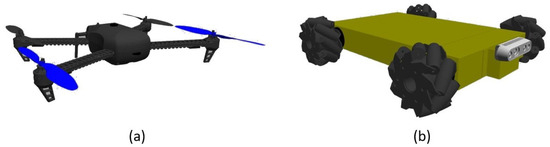

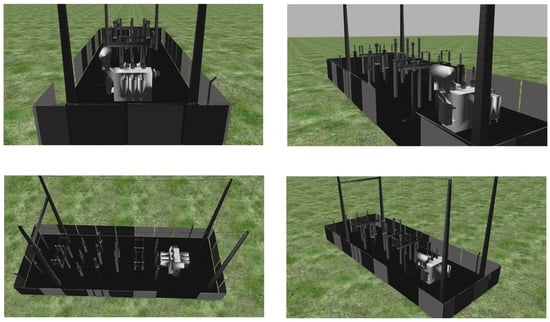

In order to create the simulation, the authors used Gazebo software Version 11 alongside ROS. Gazebo is a software simulation tool that offers a wide array of pre-built models for designers to create lifelike environments. Beyond its visual capabilities, Gazebo empowers users to establish a complete dynamic interface, encompassing factors like gravity, wind, dynamic elements, and more. ROS is an open-source middleware framework designed to streamline the development and control of robotic systems. Its architecture is flexible and modular, giving the developers a powerful tool to create and handle the many processes in the robotic world. Figure 10 visually represents the simulated UAV and UGV models employed in the Gazebo simulation software. Figure 11 shows the Gazebo’s world with the electrical substation model, where all simulations were conducted.

Figure 10.

Gazebo’s models. (a) UAV iris model. (b) UGV model.

Figure 11.

Simulated world created on Gazebo.

4.2. Simulations

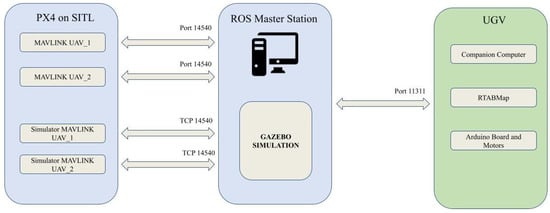

The proposed methodology for CPP in a dynamic environment was verified using Software-in-the-Loop (SITL) simulations using the PX4 open-source flight control platform [53]. SITL is a technique that involves testing a system’s control software in a computer simulation environment, offering advantages like saving time and resources, security, ease of repetition, iterative development, evaluating edge cases, and supporting training in safe and controlled environments [54]. The simulations involved an Iris quadrotor model within the Gazebo robot simulator, as illustrated in Figure 10a. The communication between the simulated quadrotor and PX4 was established through the MAVLink API. This API defines a set of messages facilitating the transfer of sensor data from the simulated environment to PX4, and reciprocally, it conveys motor and actuator values applied to the simulated vehicle [55]. Besides that, authors also applied the UGV (i.e., Figure 10b) developed by Santos et al. [56] during simulations inside Gazebo.

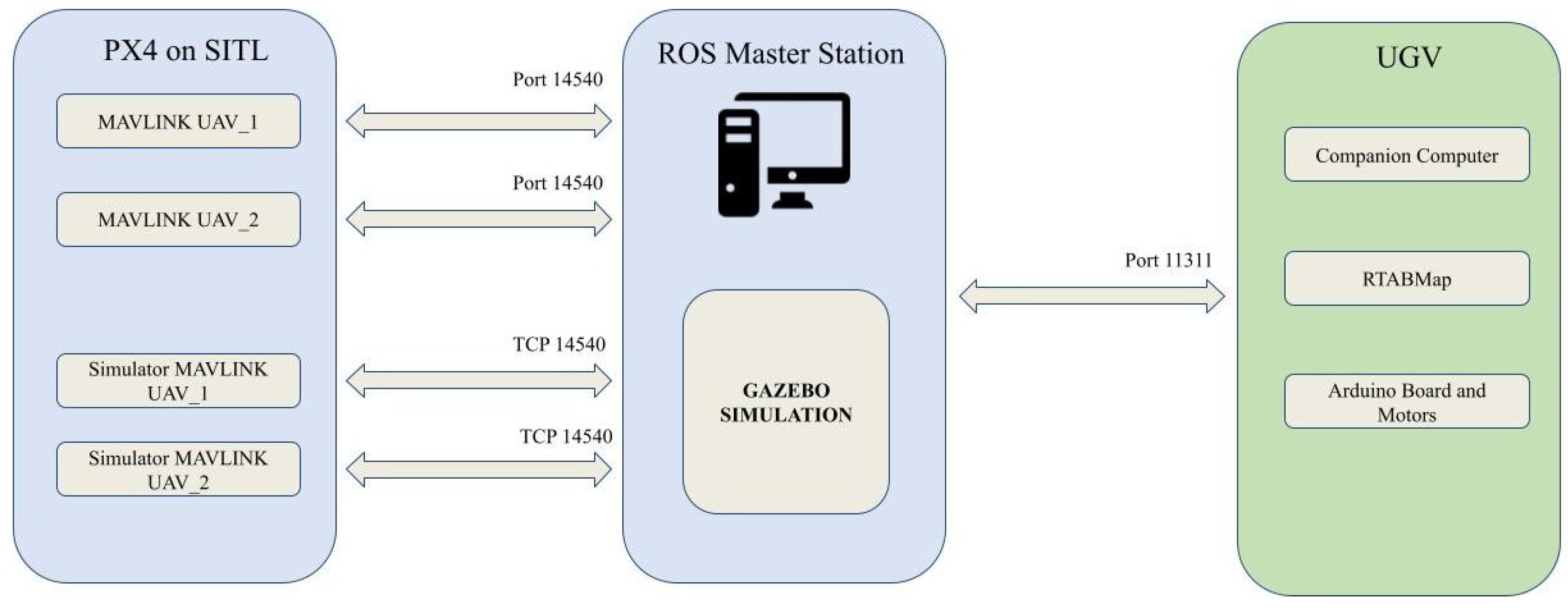

4.2.1. System Intregration

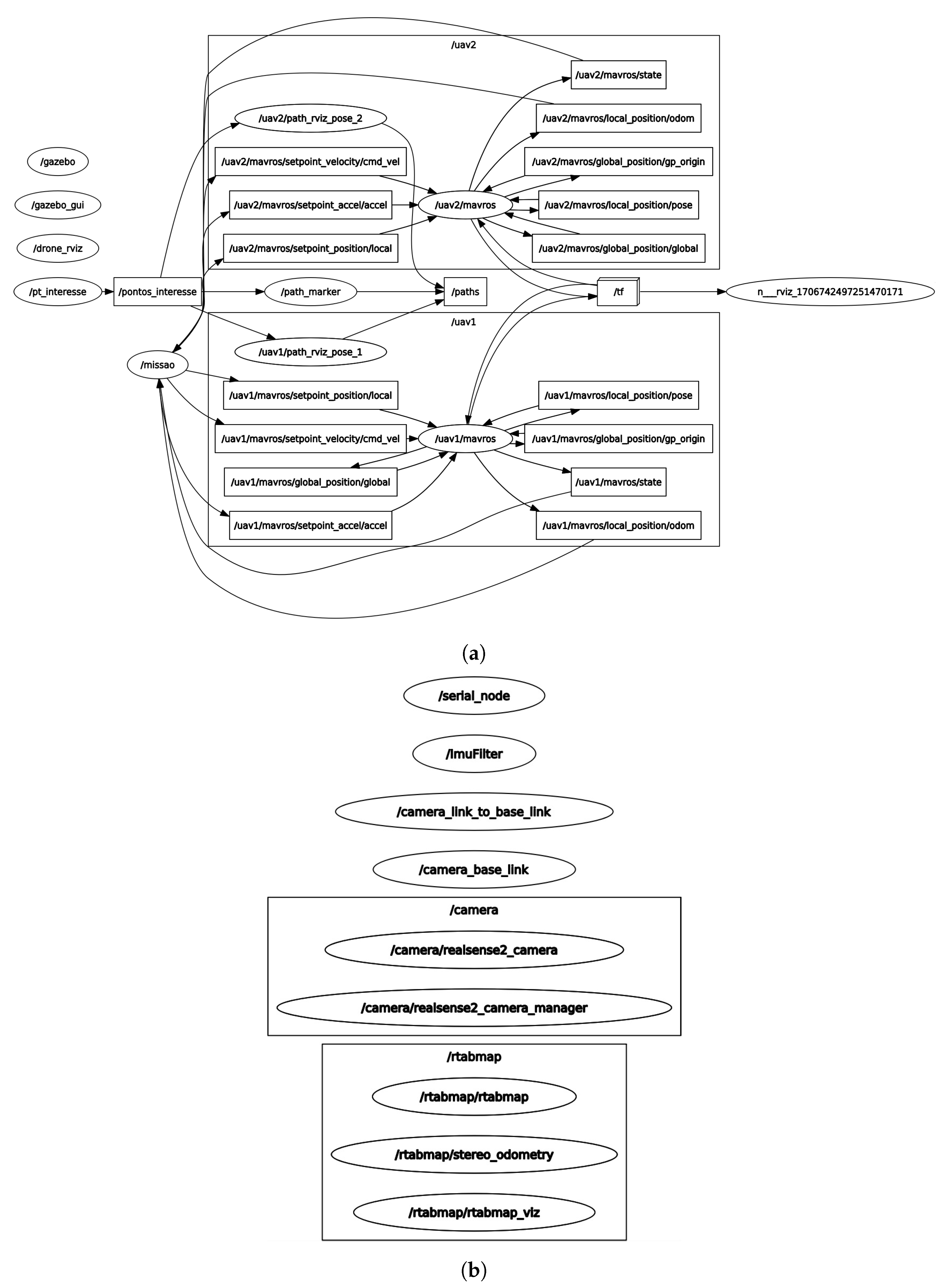

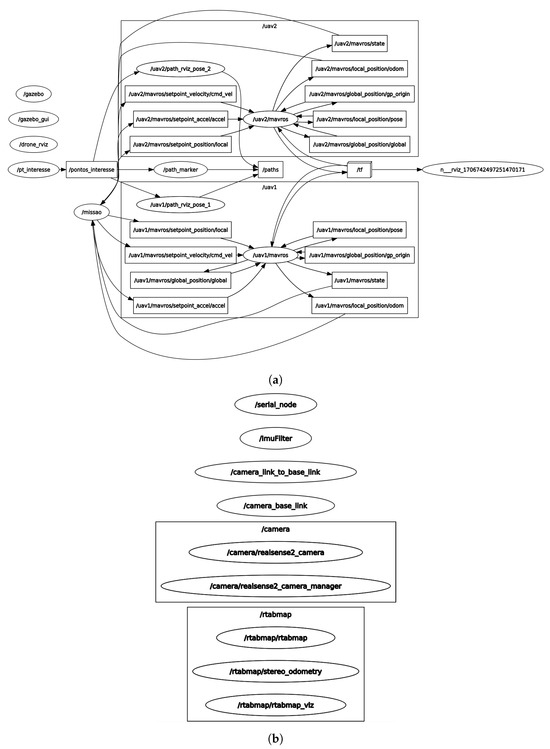

The interconnection among these systems was performed using ROS. Figure 12 shows a diagram with the hierarchy of these connections. This figure has three main blocks. The block PX4 on SITL represents the two simulated UAVs within the PX4 SITL environment, where the PX4 autopilot firmware is running. This simulates the UAVs’ behavior and provides a controlling interface. Note that the MAVlink protocol is used for communication between autopilots and onboard systems or ground stations. The other block, the ROS Master Station, represents the ROS framework to build the robotic system. The ROS Master Station serves as the central coordinator for communication within a ROS-based system. Finally, the last block, UGV, represents the ground-based robot that has a companion computer that has an onboard processing unit that processes the path planning tasks and the Real-Time Appearance-Based Mapping (RTAB-Map) package used for real-time simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM).

Figure 12.

Communication hierarchy of robotic systems.

The ROS Master is a central component that manages the registration and discovery of nodes within the ROS system, integrating the communication among the subsystems inside each agent. The communication in ROS is based on a publish-subscribe model and a service-oriented architecture, allowing different components to exchange data and information. One of these elements is the Node, which represents individual software modules that serve as a key element in decomposing a robotic system. These nodes communicate with each other through an ROS structure known as topics. Figure 13 illustrates essential nodes, topics, and their intercommunication during simulations. The UGV (Figure 13b) is performing the inspection using the node /rtabmap, and for its navigation, it is using /imuFilter and /camera nodes. Its companion computer communicates with the motors through /serial_node. Regarding the UAVs, Figure 13a, the topics with the points of interest are sent from the node /pt_interesse to the nodes /missao, /uav1/path_rviz_pose_1, and /uav2/path_rviz_pose_2. Thus, the robots know exactly the points being inspected, in case one UAV has to stop is currently mission. Note that the robots are communicating through MAVROS (nodes /uav1/mavros and /uav2/mavros).

Figure 13.

Active ROS nodes and topics. (a) UAV1 and UAV2 nodes/topics. (b) UGV nodes/topics.

As mentioned, the UGV uses the RTAB ROS package for simultaneous mapping and localization of the robot. Additionally, the robot computes wheel odometry. The companion computer processes the fused odometry data through the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) The companion computer also handles mapping, communicating with the Arduino, as detailed in [56]. The Arduino board is responsible for controlling the motors, enabling the execution of movements based on the processed mapping and localization information.

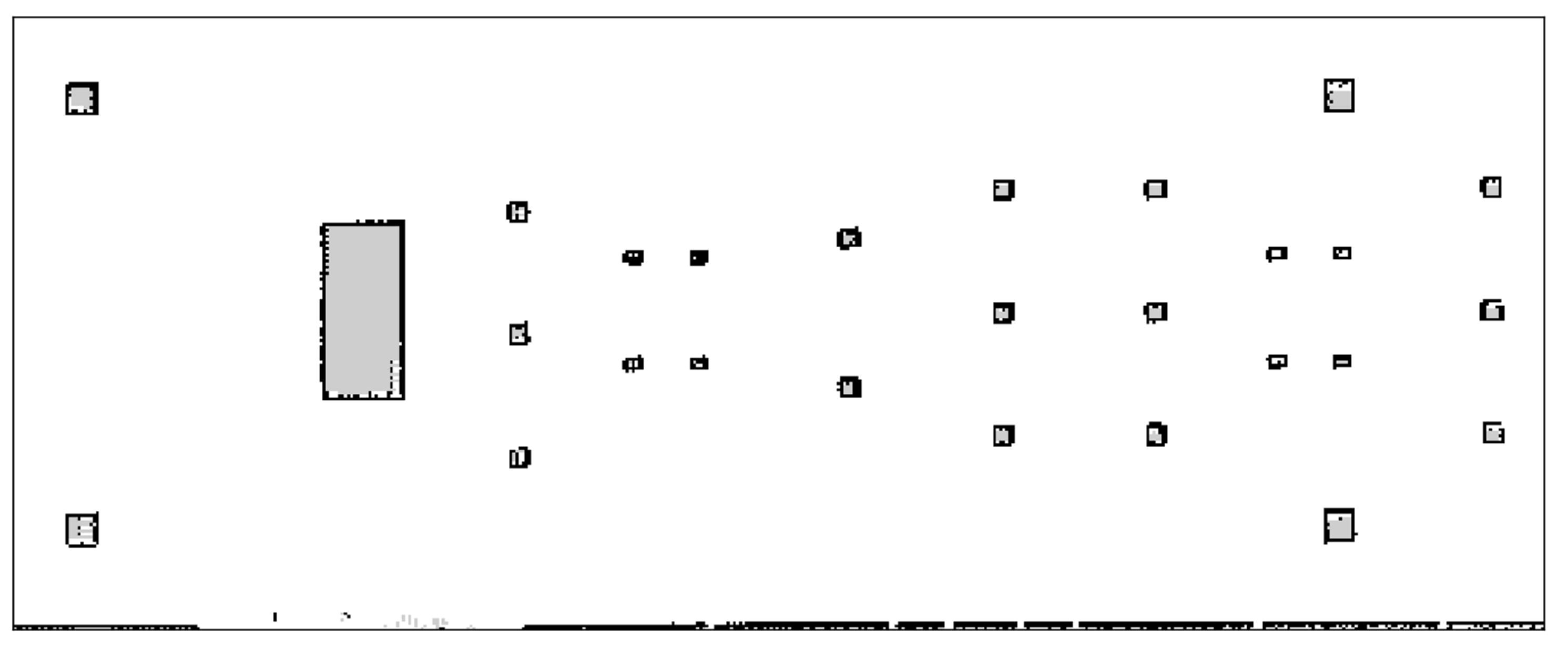

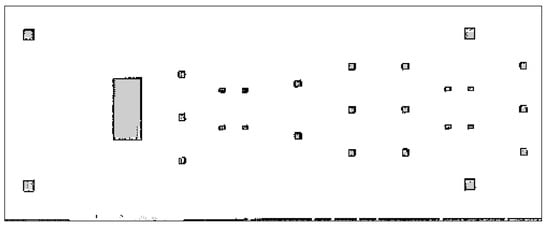

4.2.2. Mapping

The mapping topic, depicted in Figure 13, is important in this project. This function allows the robots to understand and navigate the environment, assisting them in detecting and avoiding obstacles during inspection tasks. The mapping also facilitates localization to determine their positions relative to the inspection area, ensuring data collection and task execution. In this sense, all agents interact with this topic, reading from and updating it with their sensors. The construction of the map topic initially involved the UGV navigating through the environment, sending camera readings to the RTAB package [57]. The map was saved after the explorations and can be transformed into an image, as shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

A 2D representation of the substation environment.

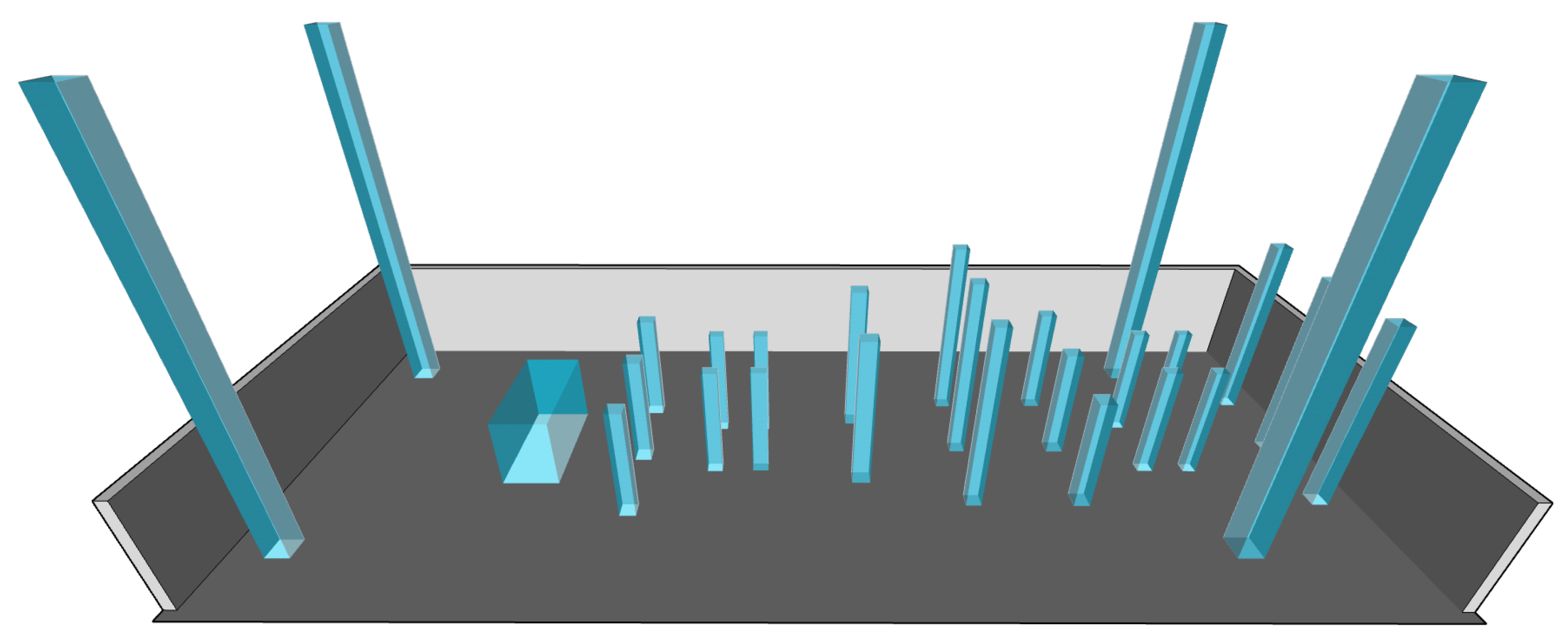

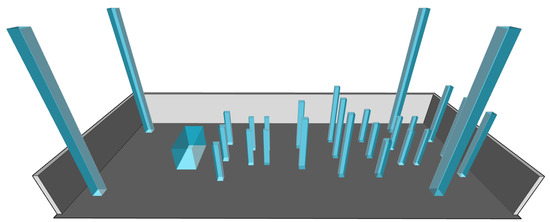

One of the drones was deployed to achieve a 3D representation of the map topic, similar to what was accomplished with the UGV. It conducted flights at specific heights, using its built-in camera to transmit information to the OctoMap Mapping Framework (Octomap) mapping package [58]. This process aimed to generate a comprehensive 3D representation of the environment. The aircraft flies at a specific height to acquire images of the surroundings. These captured images are processed and used in the OctoMap framework to estimate each voxel’s occupancy in the 3D space. The outcomes of these readings are depicted in Figure 15, where a 3D modeling software was employed to refine the grids, providing a better data interpretation. Note that this process can provide valuable information about the environment, including the locations of obstacles and free space.

Figure 15.

A 3D representation of the substation environment.

4.3. Coverage Path Planning

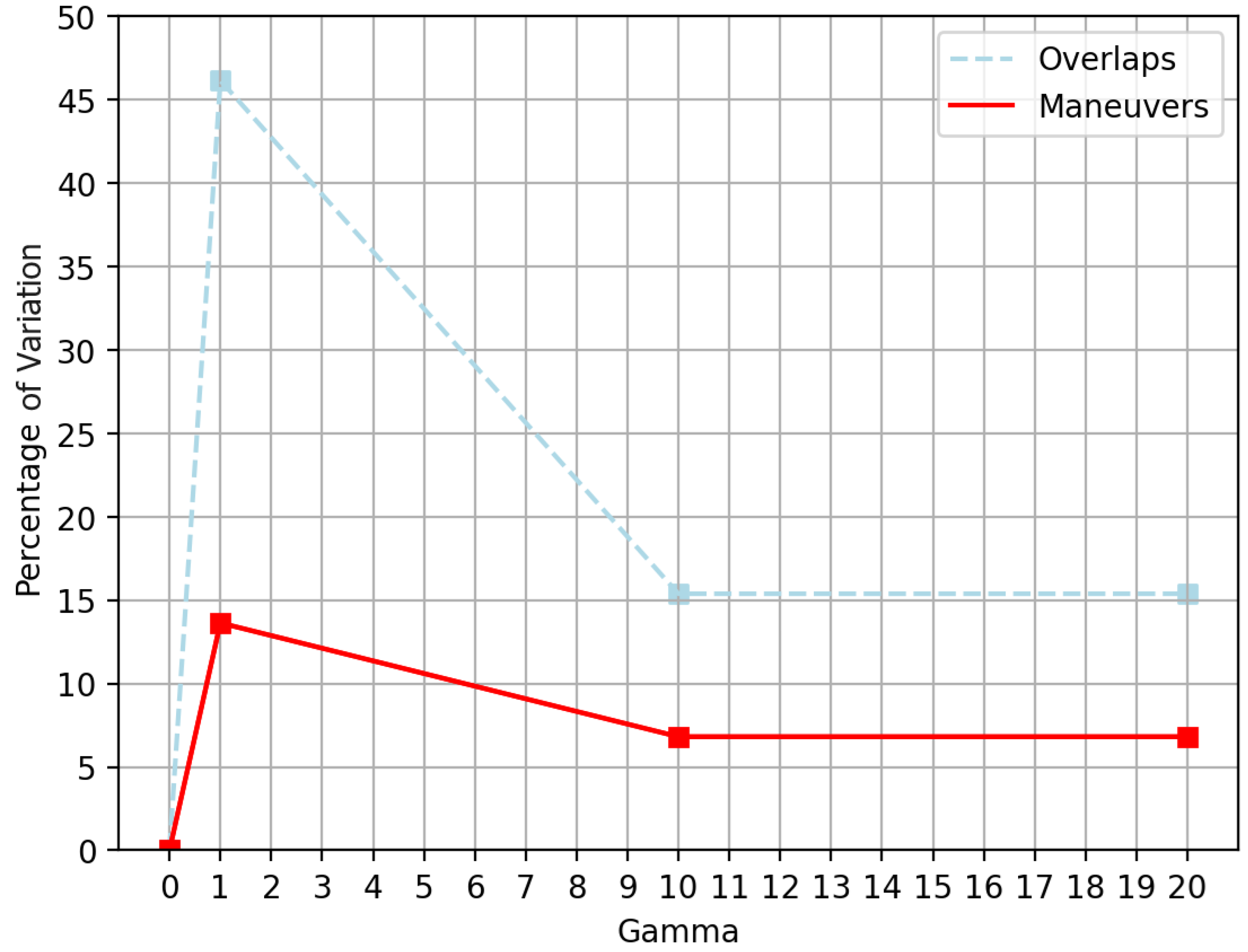

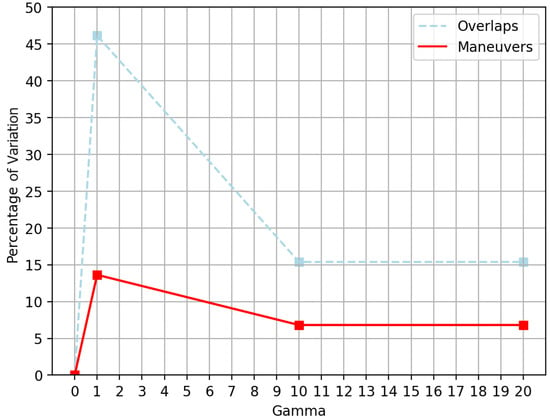

Tuning Wavefront Algorithm

Tuning the Wavefront algorithm involves choosing different values for the discount factor () already presented in Equation (3). This parameter influences the cost function used in path planning and directly impacts the algorithm’s behavior and the quality of the generated paths. As usual for coverage path plannings, the number of overlaps and maneuvers on the generated path was considered to benchmark the results. The events generated during simulations are all equal, i.e., they all have identical starting, goal points, and free areas. Figure 16 shows how the variation of the variable changes the results. As can be seen, the best results are found using gamma near 1, compared with those found adopting only distance transform.

Figure 16.

Wavefront benchmark. Dashed lines represent the overlaps, and red lines represent the maneuvers.

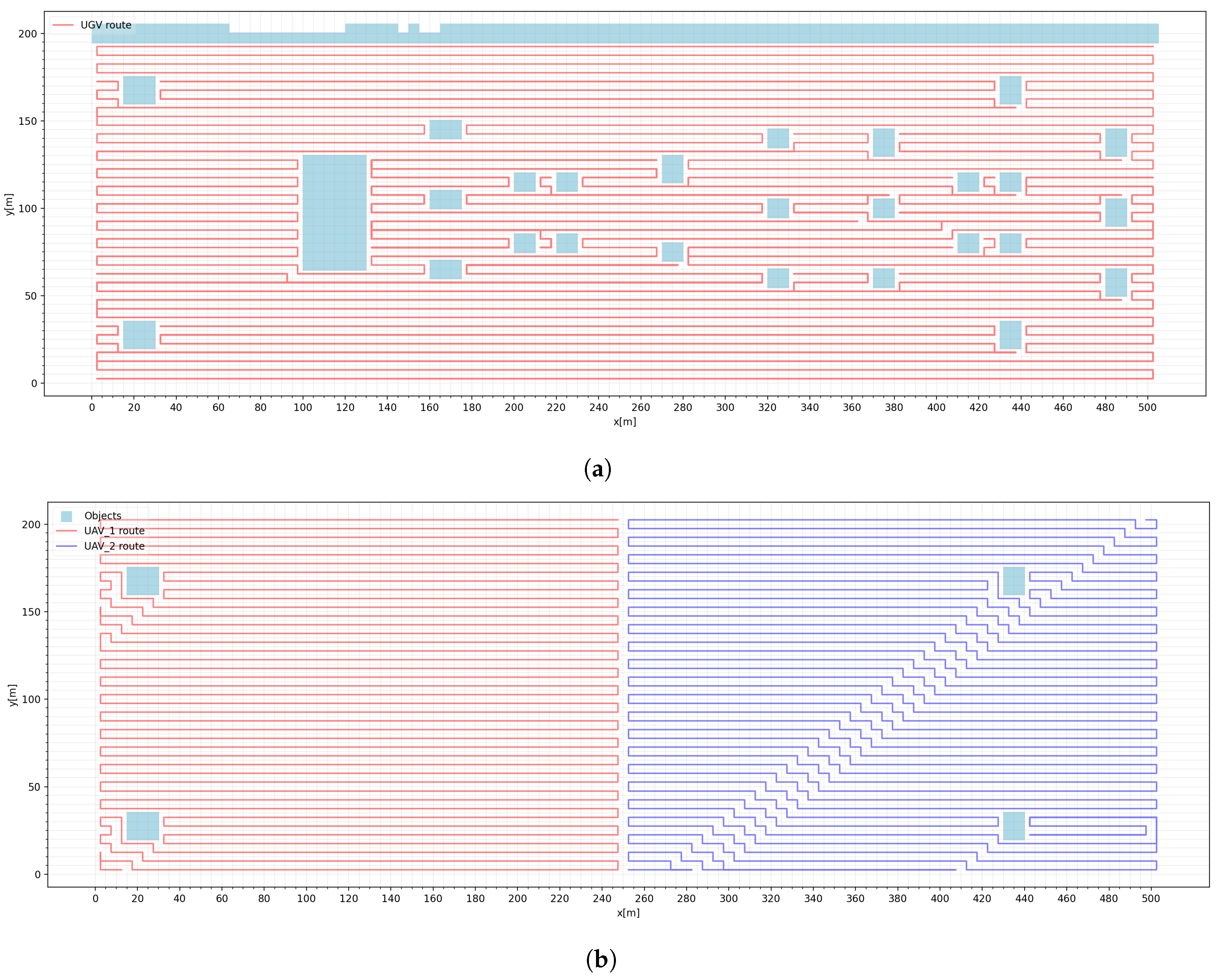

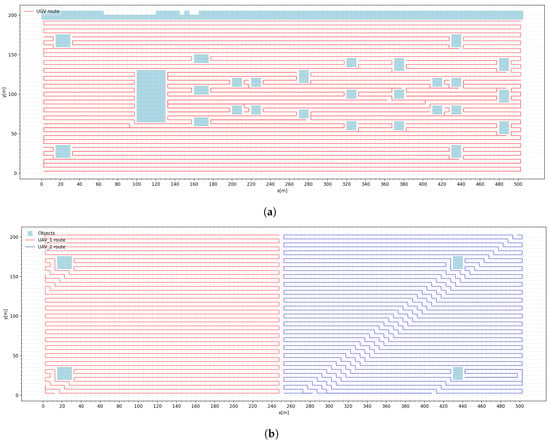

After applying the developed coverage path planning to the map, it was possible to trace the route for the UAVs and UGV agents. Figure 17 gives the path constructed by the Wavefront algorithm. Figure 17a shows the planned path for the UGV. Similarly, Figure 17b displays the paths planned for the UAVs, highlighting their respective routes. These paths represent the optimal trajectories identified by the algorithm, considering the Wavefront tuning by adjusting the discount factor ().

Figure 17.

Map route generated by wavefront coverage path planning. (a) Planning UGV path. (b) Planning UAV paths.

4.4. ROS Implementation

During simulations, the routes defined in the last section were not fixed. Indeed, they changed many times due to battery scarcity, object avoidance, or even when agents lost communication with the ROS master. The proposed framework established specific routines for these three scenarios to mitigate these challenges.

4.4.1. Battery Scarcity

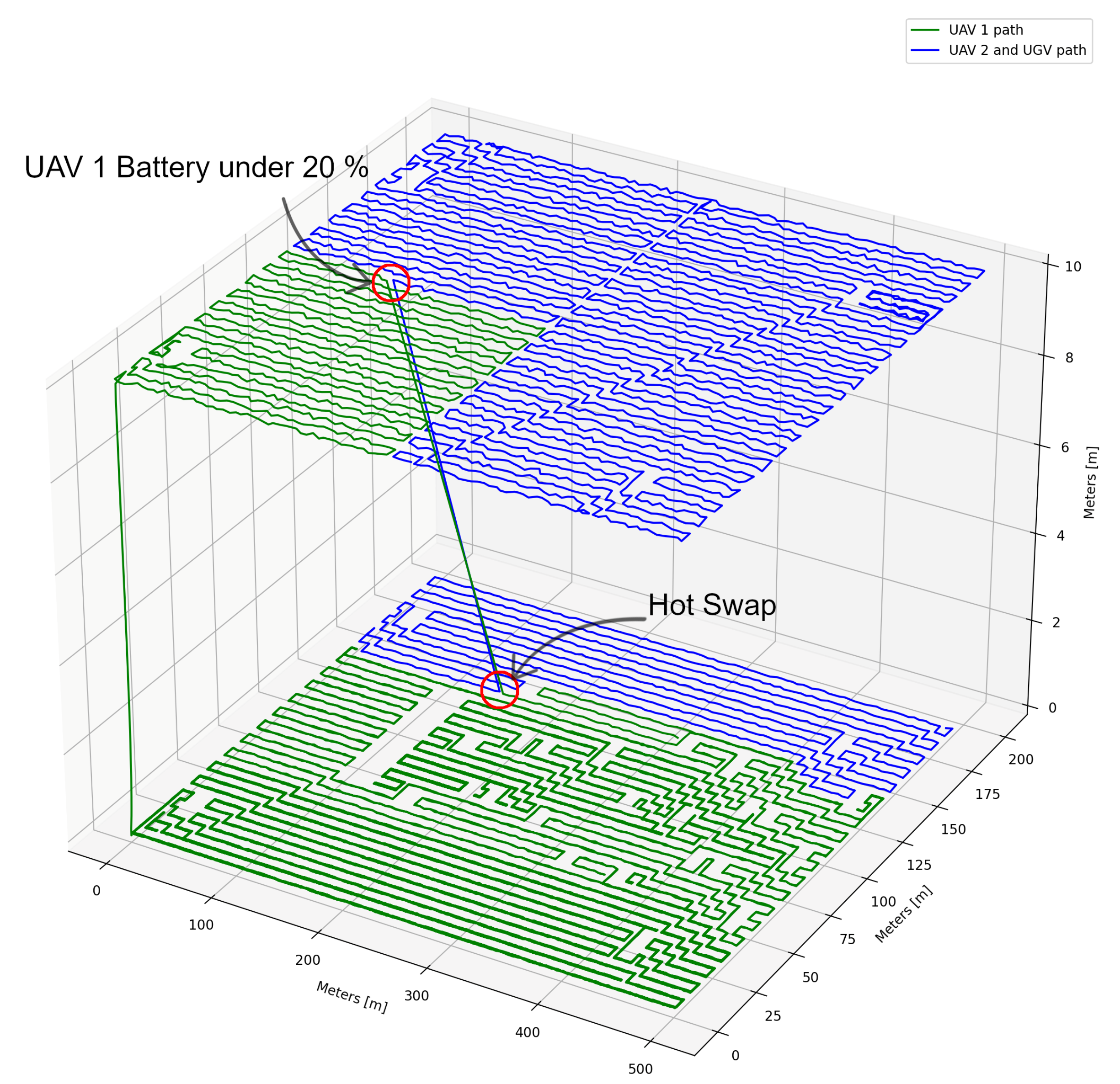

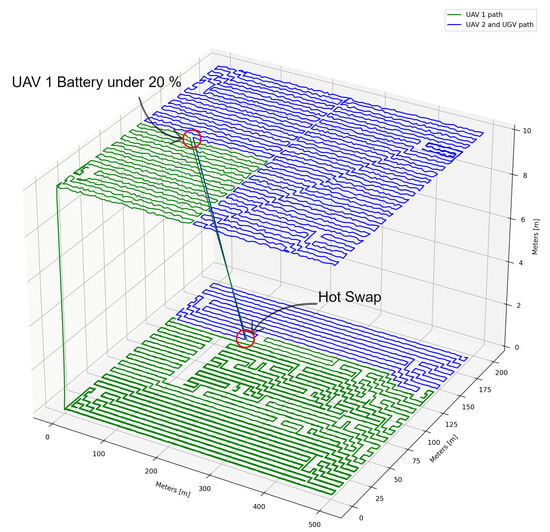

In this test scenario, UAV1 starts the mission from the ground, and UAV2 docks onto the UGV. UAV1 and UGV begin to follow their pre-determined routes until UAV1’s battery level drops to 20%; by then, the battery routine is evoked. First, the UGV stops, and UAV2 takes off until it reaches its inspection height; then, UAV1 starts to trace the route to land on UGV and performs the hot swap; when the UAV1 landing process is over, and the hot swap is performed, UGV and UAV2 continue their paths. This routine continues until the mission is over. Figure 18 shows the battery scarcity routine during a simulation.

Figure 18.

Simulation for battery scarcity routine. The green line represents the path of UAV1, and the blue line is the path of UAV2 and UGV.

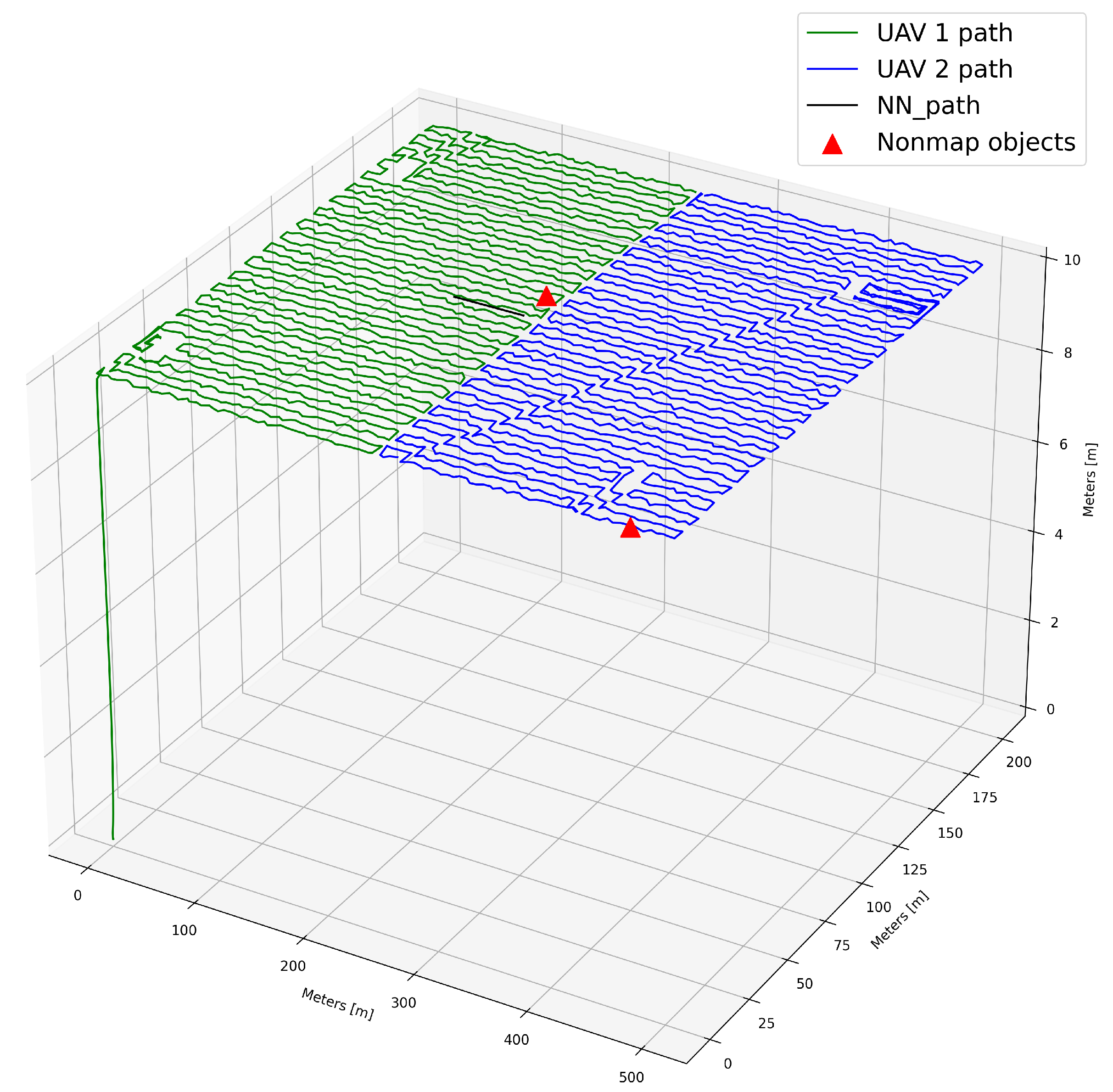

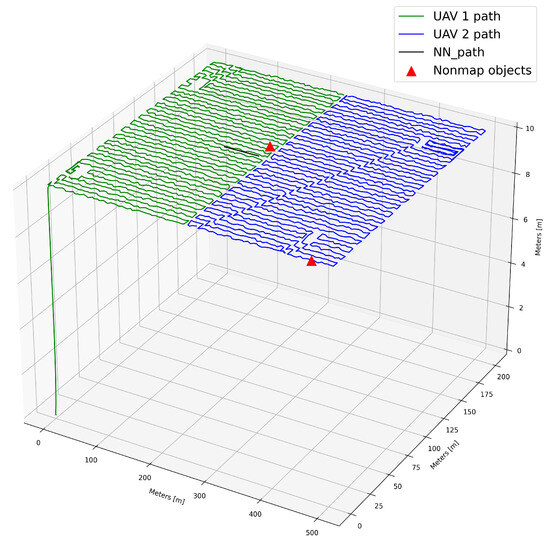

4.4.2. Avoiding Unmapped Objects

For this simulation, the authors created five random objects with sizes varying from 1 grid occupancy to 10 grids. The simulation started, as described in the battery scarcity routine. Still, this time, when one agent faces an unexpected object, the unmapped routine is called, and the obstacle avoidance algorithm based on neural networks performs the path planning. This process is shown in Figure 19.

Figure 19.

Simulation for avoiding unmapped objects. The green line represents the path of UAV 1, the blue line is the path of UAV 2, and the black line is the NN path.

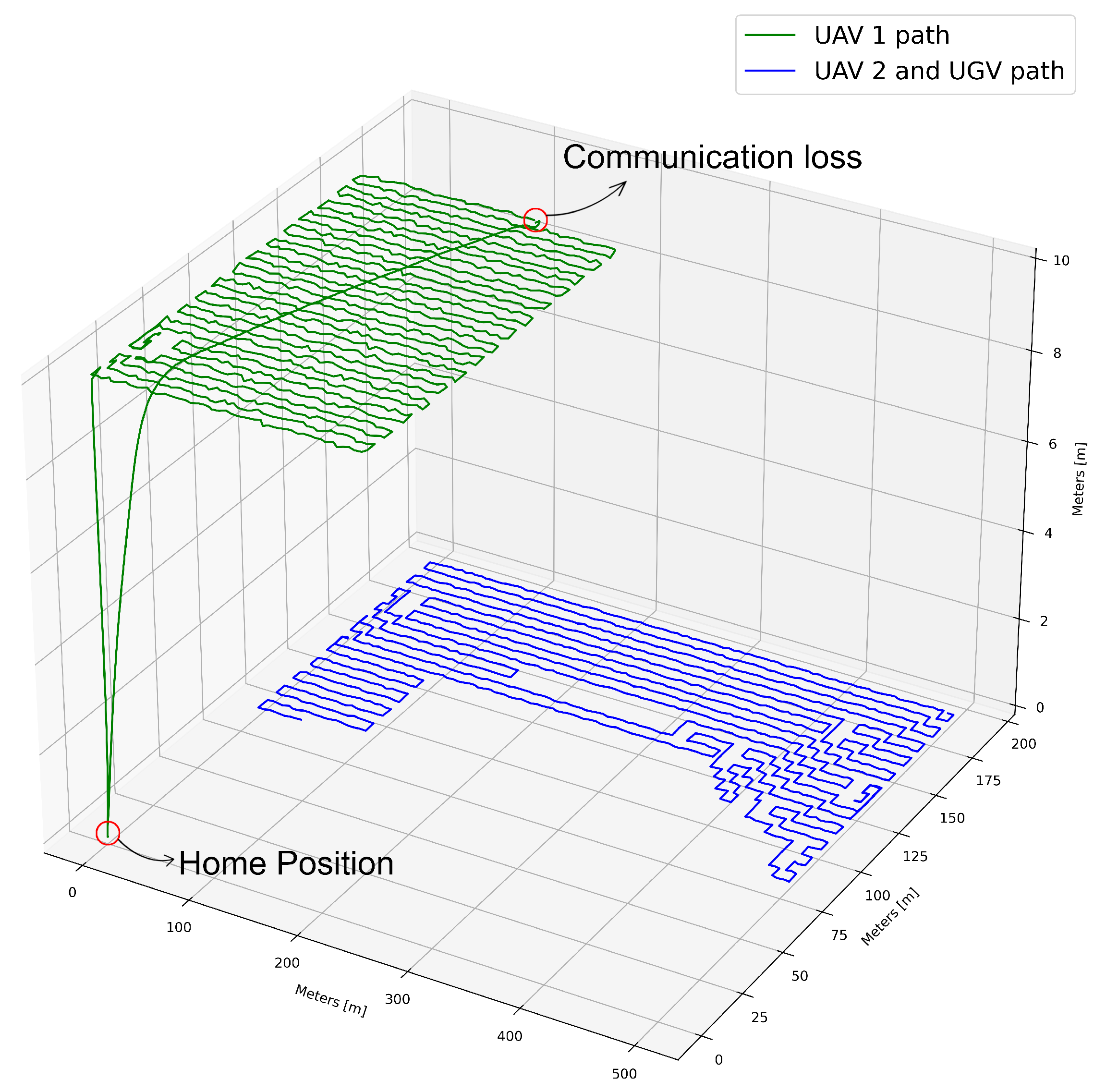

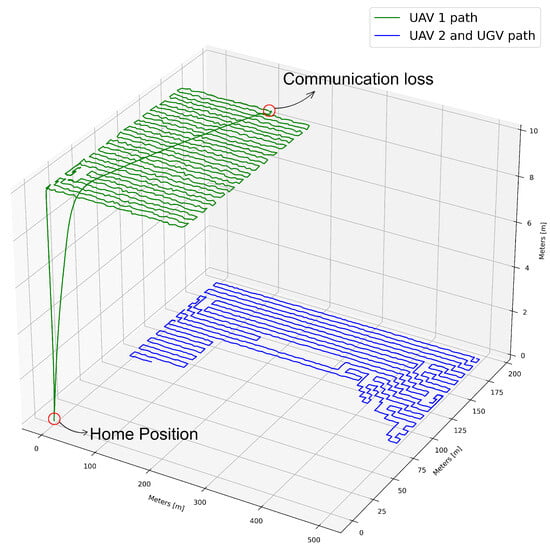

4.4.3. Communication Loss

Localization and map information are always shared between the agents in this proposed framework. The authors created the communication loss routine to enhance operational safety in these scenarios. It begins when some agent stops receiving connection information from the ROS master. Then, the flying UAV will return to its takeoff position (i.e., Return To Home (RTH) procedure); if its battery is under 20%, it will look for the nearest safe place and try to land on it (or, RTH). During the loss routine, the UGV and nested UAV will stop their missions and wait until system communication is fully recovered. This process is shown in Figure 20.

Figure 20.

Simulationfor communication loss with battery up to 20%. The green line represents the path of UAV1, and the blue line is the path of UAV2 and UGV.

4.4.4. Time Analysis

Time spent during a mission execution is crucial. Although this paper does not intend to develop an optimum strategy or even a flawless implementation for multiple scenarios, the authors decided to present some time analysis and path comparison between the expected results and the actual ones given by simulation. Table 3 compiles all the results obtained through all simulations in the proposed scenarios. Note that in the hot swap battery case, the mean time cost to complete the mission is 28 minutes. The mean time cost is 29 minutes in the scenario with unmapped objects.

Table 3.

Compilation of results obtained in simulations.

4.4.5. Testing Other CPP into the Architecture

Performing a CPP mission is not a simple task. As discussed in Section 1, the environment plays a crucial role in the decision of which strategy would be used. Not only that, but computational time and path quality are also important. To show the modular characteristics and versatility of the proposed architecture, the authors decided to recreate the same simulations in the substation world, but this time with different coverage path planning strategies. It is important to say that the results only reflect the algorithm’s characteristics, i.e., the Dijkstra algorithm returns the best possible path but with high computational cost, and A* returns a fast path, but has no guarantee to explore all the environment, or even Boustrophedon cellular decomposition, a classic CPP strategy, may also return a path with many overlaps. Some results applying these algorithms during the simulation in the substation world are shown in Table 4. As expected, Dijkstra’s algorithm suffers from computational cost when facing the substation environment. Like Dijkstra, A* takes a long time to return a path and only covers 87% of the map. Indeed, this number can be increased by raising the exploration ratio, but it would also increase time. Wavefront and Boustrophedon have similar results during the simulations, with just a 4% difference in overlapping.

Table 4.

Simulation with diferent coverage path planning algorithms.

4.5. Discussion

From the results, it is possible to verify that the planned paths for the UAVs and UGV demonstrate the proposed methodology’s efficacy in guiding the robots through the inspection environment. The generated paths effectively balance coverage of the area of interest while minimizing traversal distance and avoiding obstacles.

The developed methodology exhibits scalability as it allows for deploying this framework in other inspection scenarios with different environmental conditions, mission requirements, and number of robots. The modular design and the flexibility of ROS-based communication enable the easy integration of additional sensors, platforms, or functionalities to accommodate evolving mission needs.

It is important to highlight that a safety point is configured for all robots in case of communication loss. As described before, this safety point is called Return To Home, or RTH. This procedure was chosen due to the peculiarities of the electrical substation scenario. Many commercial robots can automatically return to their starting point (RTH) when they lose communication with the remote control. This standard safety measure prevents the robotic system from navigating away and getting lost. The system can record communication loss (such as a ROSbag file) as a significant event and notify relevant human-in-the-loop process operators so they can take appropriate action. Furthermore, to minimize system downtime during the exchange of UAVs, that is, when one UAV continues the mission and the other proceeds to land onto the UGV, there is a synchronization to continue the mission.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

This research proposed a strategy to assist the cooperation of heterogeneous robot teams that comprise two UAVs and one UGV. These robots cooperate in an inspection mission of an electrical substation, which is considered a dynamic environment once it has obstacles such as conduits, pipes, structural components, and operators that circulate in this field. The robots have partial knowledge of the environment. The main contributions included the introduction of a novel cooperation path planning framework with a robust CPP algorithm and adaptive path planning for obstacle avoidance. The proposed cooperation strategy gives more capabilities for the UAVs to perform aerial inspections and continuous map updates, while UGV contributes to ground-level inspections and assists the UAVs. Simulations were conducted using ROS and the Gazebo platform. The outcomes demonstrated the functionality of the proposed approach in a semi-realistic environment simulation as proof of concept to demonstrate the robot team’s adaptability through the proposed strategy.

This research presents a potential real-world application. Cooperative robotic systems can be applied in critical infrastructure inspections like industrial plants, network transportation, and promising responses to environmental monitoring, precision agriculture, search and rescue, and urban surveillance. In order to advance from simulated environments to real-world testing, it is important to ensure that the robotic hardware and software systems are robust and reliable for deployment in dynamic, real-world settings. Our robotic system is already simulated in SITL with Ardupilot firmware to minimize discrepancies between simulation and reality. Using Ardupilot firmware in simulation offers several advantages, including simulating real-world scenarios and validating our strategies in a controlled environment. However, extensive testing and validation in controlled environments, such as test facilities or controlled outdoor spaces, are crucial for assessing the system’s functionality, reliability, and safety. In this sense, the authors intend to use real robots in a real-world scenario.

Other future works include the development of strategies for team reconfiguration and collaboration between robots to improve the overall efficiency and adaptability of the system. Investigating methods for efficient information sharing, coordination, and decentralized decision making could lead to more intelligence behaviors among the heterogeneous robot team.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.M.B.S., G.G.R.d.C. and M.F.P.; methodology, T.M.B.S., G.G.R.d.C. and M.F.P.; validation, G.G.R.d.C.; formal analysis, F.A.A.A., M.F.P. and J.L.; investigation, G.G.R.d.C. and M.F.P.; writing—original draft preparation, G.G.R.d.C. and M.F.P.; writing—review and editing, F.A.A.A., G.G.R.d.C., M.F.P., L.d.M.H., D.B.H. and J.L.; visualization, M.F.P., J.L. and G.G.R.d.C.; supervision, M.F.P.; project administration, M.F.P. All authors have read and agreed to submit the current manuscript version.

Funding

The authors also would like to thank their home Institute, CEFET/RJ, the federal Brazilian research agencies CAPES (code 001) and CNPq, and the Rio de Janeiro research agency, FAPERJ, for supporting this work.

Data Availability Statement

The source-codes are https://github.com/gelardrc/mixed_mission.git, accessed on 2 January 2024.

Acknowledgments

The authors also would like to thank their home Institute CEFET/RJ, the federal Brazilian research agencies CAPES (code 001), CNPq, and the Rio de Janeiro research agency FAPERJ through the funding JOVEM CIENTISTA DO NOSSO ESTADO-2021 (Processo SEI260003/005659/2021) for supporting this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AGVs | Automated Guided Vehicles |

| AUVs | Autonomous Underwater Vehicles |

| CNNs | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| CPP | Coverage Path Planning |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| DRL | Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| DQN | Deep Q-Network |

| MRTA | Multi-Robot Task Allocation |

| NN | Neural Networks |

| Octomap | OctoMap Mapping Framework |

| RRT | Rapidly Exploring Random Trees |

| RTAB | Real-Time Appearance-Based Mapping |

| SITL | Software-In-The-Loop |

| UAVs | Unmanned Aerial Vehicles |

| UGVs | Unmanned Ground Vehicles |

| USVs | Unmanned Surface Vehicles |

References

- Sinnemann, J.; Boshoff, M.; Dyrska, R.; Leonow, S.; Mönnigmann, M.; Kuhlenkötter, B. Systematic literature review of applications and usage potentials for the combination of unmanned aerial vehicles and mobile robot manipulators in production systems. Prod. Eng. 2022, 16, 579–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, G.S.; Teixeira, M.; Cantieri, A.; Lima, J.; Pereira, A.I.; Valente, A.; Castro, G.G.d.; Pinto, M.F. Cooperative Heterogeneous Robots for Autonomous Insects Trap Monitoring System in a Precision Agriculture Scenario. Agriculture 2023, 13, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narváez, E.; Ravankar, A.A.; Ravankar, A.; Emaru, T.; Kobayashi, Y. Autonomous vtol-uav docking system for heterogeneous multirobot team. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2020, 70, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almadhoun, R.; Taha, T.; Seneviratne, L.; Zweiri, Y. A survey on multi-robot coverage path planning for model reconstruction and mapping. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madridano, Á.; Al-Kaff, A.; Flores, P.; Martín, D.; de la Escalera, A. Software architecture for autonomous and coordinated navigation of uav swarms in forest and urban firefighting. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, N.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yi, S.; Luo, W.; Sycara, K. Adaptive informative sampling with environment partitioning for heterogeneous multi-robot systems. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 25–29 October 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 11718–11723. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, M.F.; Melo, A.G.; Marcato, A.L.; Urdiales, C. Case-based reasoning approach applied to surveillance system using an autonomous unmanned aerial vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 26th International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE), Edinburgh, UK, 19–21 June 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1324–1329. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, F.A.A.; Hovenburg, A.; de Lima, L.N.; Rodin, C.D.; Johansen, T.A.; Storvold, R.; Correia, C.A.M.; Haddad, D.B. Autonomous Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in Search and Rescue Missions Using Real-Time Cooperative Model Predictive Control. Sensors 2019, 19, 4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biundini, I.Z.; Melo, A.G.; Coelho, F.O.; Honório, L.M.; Marcato, A.L.; Pinto, M.F. Experimentation and simulation with autonomous coverage path planning for uavs. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2022, 105, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque Vega, L.F.; Lopez-Neri, E.; Arellano-Muro, C.A.; Gonzalez Jimenez, L.E.; Ghommam, J.; Carrasco Navarro, R. UAV Flight Instructional Design for Industry 4.0 based on the Framework of Educational Mechatronics. In Proceedings of the IECON 2020 The 46th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Singapore, 18–21 October 2020; pp. 2313–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; Li, X.; Dang, D.; Dou, H.; Wang, K.; Lou, A. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) Remote Sensing in Grassland Ecosystem Monitoring: A Systematic Review. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, G.G.D.; Berger, G.S.; Cantieri, A.; Teixeira, M.; Lima, J.; Pereira, A.I.; Pinto, M.F. Adaptive Path Planning for Fusing Rapidly Exploring Random Trees and Deep Reinforcement Learning in an Agriculture Dynamic Environment UAVs. Agriculture 2023, 13, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro, G.G.; Pinto, M.F.; Biundini, I.Z.; Melo, A.G.; Marcato, A.L.; Haddad, D.B. Dynamic Path Planning Based on Neural Networks for Aerial Inspection. J. Control. Autom. Electr. Syst. 2023, 34, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakhatreh, H.; Sawalmeh, A.H.; Al-Fuqaha, A.; Dou, Z.; Almaita, E.; Khalil, I.; Othman, N.S.; Khreishah, A.; Guizani, M. Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs): A survey on civil applications and key research challenges. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 48572–48634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stek, T.D. Drones over Mediterranean landscapes. The potential of small UAV’s (drones) for site detection and heritage management in archaeological survey projects: A case study from Le Pianelle in the Tappino Valley, Molise (Italy). J. Cult. Herit. 2016, 22, 1066–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Xiong, G.; Haider, M.H.; Tamir, T.S.; Dong, X.; Shen, Z. Feature selection-based decision model for UAV path planning on rough terrains. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 232, 120713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, S.; Arafat, M.Y.; Moh, S. Bio-Inspired Optimization-Based Path Planning Algorithms in Unmanned Aerial Vehicles: A Survey. Sensors 2023, 23, 3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamil, F.; Tang, S.; Khaksar, W.; Zulkifli, N.; Ahmad, S. A review on motion planning and obstacle avoidance approaches in dynamic environments. Adv. Robot. Autom. 2015, 4, 134–142. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, M.P.; Montiel, O.; Castillo, O.; Sepulveda, R.; Melin, P. Path planning for autonomous mobile robot navigation with ant colony optimization and fuzzy cost function evaluation. Appl. Soft Comput. 2009, 9, 1102–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Rosas, U.; Picos, K.; Montiel, O. Hybrid path planning algorithm based on membrane pseudo-bacterial potential field for autonomous mobile robots. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 156787–156803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Yan, W.; Cao, M. Clustering-based algorithms for multivehicle task assignment in a time-invariant drift field. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2017, 2, 2166–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Yan, W.; Ge, S.S.; Cao, M. An integrated multi-population genetic algorithm for multi-vehicle task assignment in a drift field. Inf. Sci. 2018, 453, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.; Kumar, N. Path planning techniques for unmanned aerial vehicles: A review, solutions, and challenges. Comput. Commun. 2020, 149, 270–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, I.; Choi, B.; Nielsen, P. On the training of a neural network for online path planning with offline path planning algorithms. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 57, 102142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, H.; Tian, Y.C. Dynamic robot path planning using an enhanced simulated annealing approach. Appl. Math. Comput. 2013, 222, 420–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Li, G.; Zheng, Q.; Bai, X.; Ding, Y.; Khan, A. Path planning for wheeled mobile robot in partially known uneven terrain. Sensors 2022, 22, 5217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guetta, Y.; Shapiro, A. On-Board Physical Battery Replacement System and Procedure for Drones During Flight. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 9755–9762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Zhou, J.; Lin, W.T. Autonomous battery swapping system for quadcopter. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Denver, CO, USA, 9–12 June 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 118–124. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H.; Joung, J.; Kang, J. Power-efficient formation of UAV swarm: Just like flying birds? In Proceedings of the GLOBECOM 2020—2020 IEEE Global Communications Conference, Virtual Event, Taiwan, 7–11 December 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Cheraghi, A.R.; Shahzad, S.; Graffi, K. Past, present, and future of swarm robotics. In Proceedings of the Intelligent Systems and Applications: Proceedings of the 2021 Intelligent Systems Conference (IntelliSys) Volume 3, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1–2 September 2022; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 190–233. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yang, Y. Path planning of UAV-UGV heterogeneous robot system in road network. In Proceedings of the Intelligent Robotics and Applications: 12th International Conference, ICIRA 2019, Shenyang, China, 8–11 August 2019; Proceedings, Part VI 12. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 497–507. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, P.; Price, L.C.; Park, J.; Cho, Y.K. UAV-UGV cooperative 3D environmental mapping. In Proceedings of the ASCE International Conference on Computing in Civil Engineering, Atlanta, GA, USA, 17–19 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Arbanas, B.; Ivanovic, A.; Car, M.; Haus, T.; Orsag, M.; Petrovic, T.; Bogdan, S. Aerial-ground robotic system for autonomous delivery tasks. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Stockholm, Sweden, 16–21 May 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 5463–5468. [Google Scholar]

- Stentz, A.; Kelly, A.; Rander, P.; Herman, H.; Amidi, O.; Mandelbaum, R.; Salgian, G.; Pedersen, J. Real-Time, Multi-Perspective Perception for Unmanned Ground Vehicles. In Proceedings of the Unmanned Systems Symposium (AUVSI ’03), Baltimore, MD, USA, 15–17 July 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D.; Yang, C.; Zhang, T.; Yang, J.; Hiroshi, Y. A Task Allocation Approach of Multi-Heterogeneous Robot System for Elderly Care. Machines 2022, 10, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quenzel, J.; Splietker, M.; Pavlichenko, D.; Schleich, D.; Lenz, C.; Schwarz, M.; Schreiber, M.; Beul, M.; Behnke, S. Autonomous fire fighting with a UAV-UGV team at MBZIRC 2020. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Athens, Greece, 15–18 June 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 934–941. [Google Scholar]

- Langerwisch, M.; Wittmann, T.; Thamke, S.; Remmersmann, T.; Tiderko, A.; Wagner, B. Heterogeneous teams of unmanned ground and aerial robots for reconnaissance and surveillance-a field experiment. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Symposium on Safety, Security, and Rescue Robotics (SSRR), Linköping, Sweden, 21–26 October 2013; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, N.; Fink, J.; Kumar, V. Controlling a team of ground robots via an aerial robot. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, San Diego, CA, USA, 29 October–2 November 2007; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 965–970. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraa, H.; Guérin, F.; Leclercq, E.; Lefebvre, D. Optimization techniques for Multi-Robot Task Allocation problems: Review on the state-of-the-art. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2023, 168, 104492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.S.; Arshad, M.R. Coverage path planning for underwater pole inspection using an autonomous underwater vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Automatic Control and Intelligent Systems (I2CACIS), Selangor, Malaysia, 22 October 2016; pp. 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Hoang, G.; Bae, M.; Kim, J.W.; Yoon, S.M.; Yeo, T.; Sup, H.; Kim, S. Path tracking control coverage of a mining robot based on exhaustive path planning with exact cell decomposition. In Proceedings of the 2014 14th International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems (ICCAS 2014), Kintex, Republic of Korea, 22–25 October 2014; pp. 730–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, E.W. A note on two problems in connexion with graphs. Numer. Math. 1959, 1, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, P.E.; Nilsson, N.J.; Raphael, B. A formal basis for the heuristic determination of minimum cost paths. IEEE Trans. Syst. Sci. Cybern. 1968, 4, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biundini, I.Z.; Melo, A.G.; Pinto, M.F.; Marins, G.M.; Marcato, A.L.; Honorio, L.M. Coverage path planning optimization for slopes and dams inspection. In Iberian Robotics Conference; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 513–523. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Bai, Y.; Zhou, C. Coverage path planning design of mapping UAVs based on particle swarm optimization algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2019 Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Guangzhou, China, 27–30 July 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 8236–8241. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, C.S.; Mohd-Mokhtar, R.; Arshad, M.R. A comprehensive review of coverage path planning in robotics using classical and heuristic algorithms. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 119310–119342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, A.H.; Simeonov, A.; Bency, M.J.; Yip, M.C. Motion planning networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Montreal, Canada, 20–24 May 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 2118–2124. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, K.; Esfahani, M.A.; Yuan, S.; Wang, H. TDPP-Net: Achieving three-dimensional path planning via a deep neural network architecture. Neurocomputing 2019, 357, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Wang, Y. UAV Path Planning Based on Multi-Layer Reinforcement Learning Technique. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 59486–59497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelinsky, A.; Jarvis, R.A.; Byrne, J.; Yuta, S. Planning paths of complete coverage of an unstructured environment by a mobile robot. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Robotics, Atlanta, GA, USA, 2–6 May 1993; Volume 13, pp. 533–538. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis, R.; Byrne, J.; Ajay, K. An Intelligent Autonomous Guided Vehicle: Localisation, Environmental Modelling and Collision-Free Path Finding. In Proceedings of the 19th International Symposium and Exposition on Robots, Sydney, Australia, 6–10 November 1988; pp. 767–792. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Juntao, L.; Lingling, P. Multi-robot path planning based on a deep reinforcement learning DQN algorithm. CAAI Trans. Intell. Technol. 2020, 5, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Open Source Autopilot of Drone Developers. Available online: https://px4.io/ (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Ramos, G.S.; Pinto, M.F.; Coelho, F.O.; Honório, L.M.; Haddad, D.B. Hybrid methodology based on computational vision and sensor fusion for assisting autonomous UAV on offshore messenger cable transfer operation. Robotica 2022, 40, 2786–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAVLink Developer Guide. Available online: http://mavlink.io (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Santos, T.M.; Favoreto, D.G.; Carneiro, M.M.d.O.; Pinto, M.F.; Zachi, A.R.; Gouvea, J.A.; Manhães, A.; Almeida, L.F.; Silva, G.R. Introducing Robotic Operating System as a Project-Based Learning in an Undergraduate Research Project. In Proceedings of the 2023 Latin American Robotics Symposium (LARS), 2023 Brazilian Symposium on Robotics (SBR), and 2023 Workshop on Robotics in Education (WRE), Salvador, Brazil, 9–11 October 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 585–590. [Google Scholar]

- Labbé, M.; Michaud, F. RTAB-Map as an open-source lidar and visual simultaneous localization and mapping library for large-scale and long-term online operation. J. Field Robot. 2019, 36, 416–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornung, A.; Wurm, K.M.; Bennewitz, M.; Stachniss, C.; Burgard, W. OctoMap: An Efficient Probabilistic 3D Mapping Framework Based on Octrees. Auton. Robot. 2013, 34, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).