The Law of the Iterated Logarithm for the Error Distribution Estimator in First-Order Autoregressive Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Assumptions

- (A1)

- In model (1), let the sequence of errors form a stationary sequence of -mixing with unknown CDF F with a bounded second-order derivative, i.e., there exists a positive constant C () such that for all . Assume and for some . The mixing coefficient satisfies , where .

- (A2)

- The kernel function , and are integrable over the real line and satisfy

- (A3)

- The bandwidth h satisfies the following conditions:

- (A4)

- In model (1) with , let the be an estimator of with the following almost-surely (a.s.) property: there exists a positive constant C such that

- (i)

- Assumption (A1) contains the smoothness of the error CDF F and the boundness of its second derivative . It also requires the mixing coefficients satisfy , where and (p-th moment of error). If , then . It is a strong condition of mixing coefficients, which require the errors to be asymptotically independent. If , then . This requires a strong p-th moment of errors. In future research, we will try to relax the mixing coefficient condition. For more properties of α-mixing sequences, one can refer to Györfi [10], Roussas [11], Fan and Yao [12], Wang et al. [13], etc.

- (ii)

- Assumption (A2) is the common condition of kernel about non-negatively, symmetry, and integrability. Obviously, the probability density functions Gaussian kernel and Epanechnikov kernel conform to Assumption (A2). See for example, Györfi et al. [10], Roussas [11], Fan and Yao [12], Li and Racine [23], etc.

- (iii)

- (iv)

- Assumption (A4) requires that the estimator of the autoregressive parameter ρ converges almost surely at the rate . This condition plays a key role in our theoretical results, as it ensures that the effect of estimating ρ is asymptotically negligible. Without such a rate, the additional error introduced by residuals could dominate the behavior of the kernel estimator and invalidate the uniform LIL established in this paper. When are i.i.d. errors, Koul and Zhu [24] considered a generalized M-estimator for p-th order autoregression models and obtained a strong rate of convergence for M-estimators , i.e., , a.s., including the least-squares estimator; Cheng [9] used Assumption (A4) to study the -norm of in (8). When in the first-order autoregression model (1) are α-mixing random variables with common density function f and , Gao et al. [25] used the condition to study the asymptotic normality of the kernel density estimator for the error density function f. Wu et al. [26] extended the work to nonlinear autoregressive models. In the proof by Gao et al. [25], moment inequalities were used to establish the convergence in probability. However, to extend these results to almost-sure convergence, it would be necessary to employ exponential inequalities. This in turn requires additional conditions on the α-mixing coefficients, ensuring that the covariance structure of the α-mixing sequence satisfies certain summability and decay properties. The proof of such a result is highly technical and involves delicate handling of the dependence structure. Because this is beyond the scope of the present paper, we treat Assumption (A4) as a standing assumption rather than providing a full proof here, and we leave this as an important topic for our future research.

3. Main Results

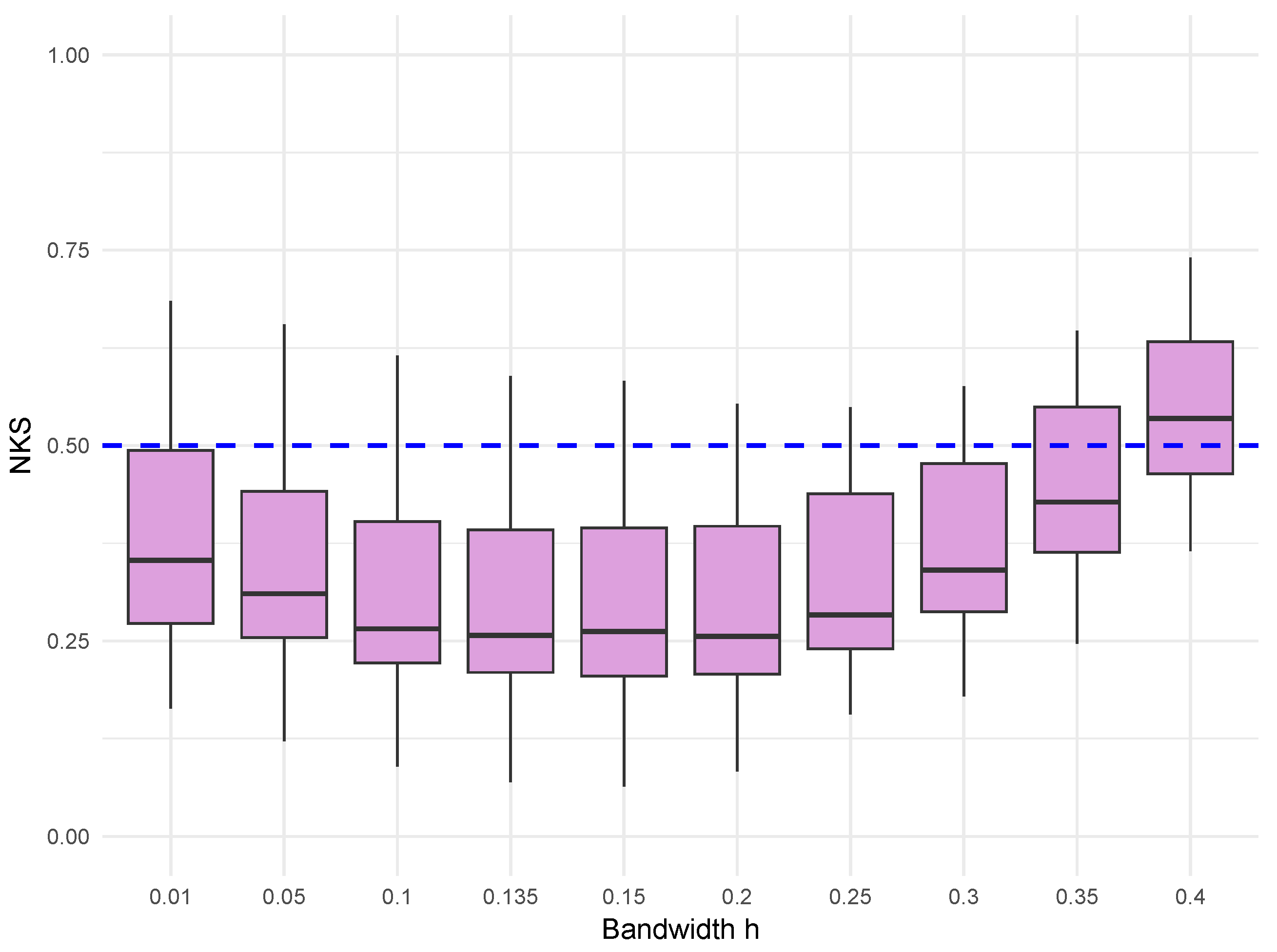

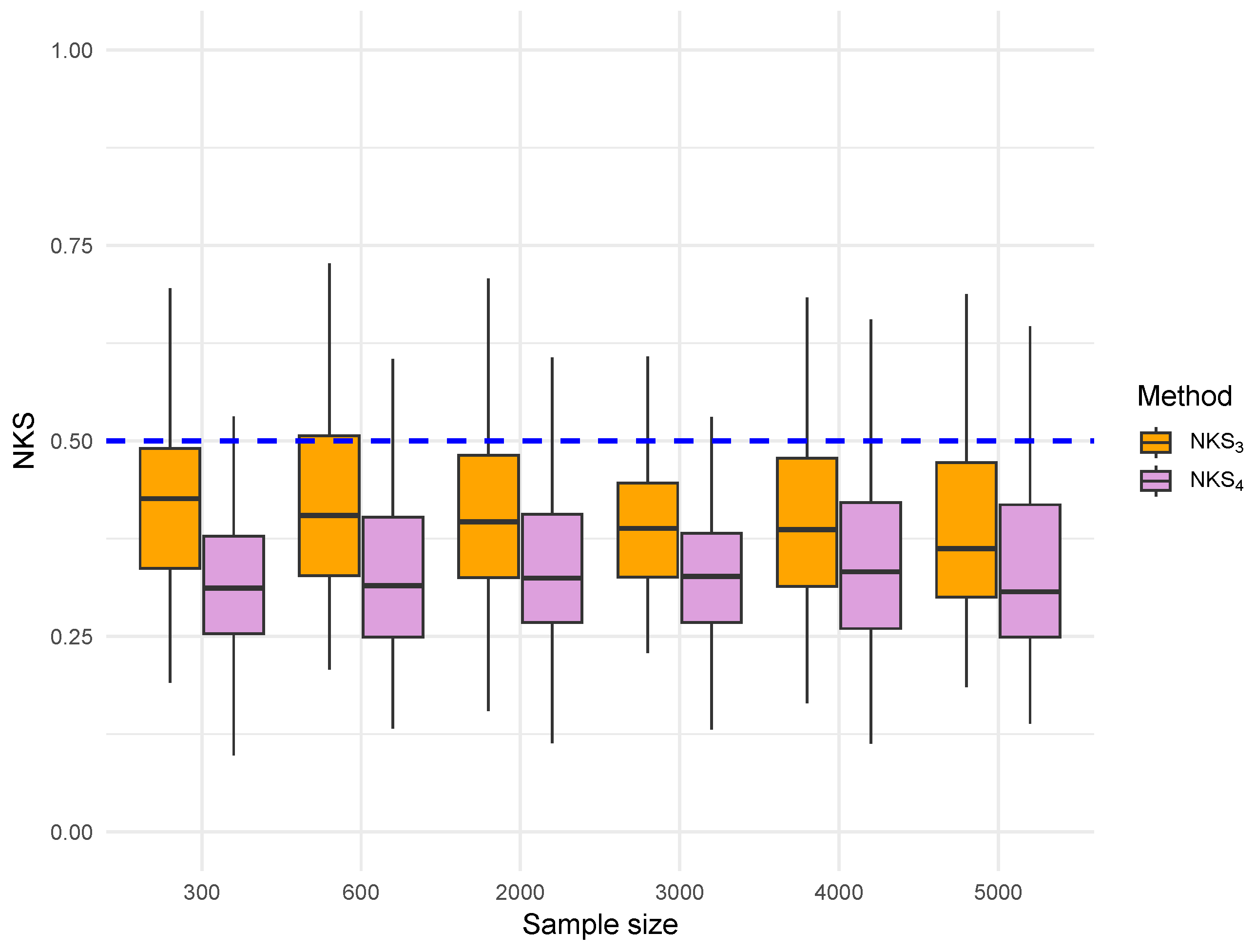

4. Simulations

- Gaussian errors: , where is a Toeplitz covariance matrix with entries , ensuring that the errors form an -mixing sequence. A Toeplitz matrix is a matrix in which each descending diagonal from left to right is constant. For more details about the Toeplitz matrix, we can refer to Trench [28]. As discussed in [29], it is easy to check that are -mixing with .

- Gamma errors: we adopt a Gaussian copula-based approach to generate random vectors with exact Gamma marginals and an approximately specified covariance matrix. Specifically, we first generate a multivariate normal vector , where R is the correlation matrix corresponding to the target covariance matrix . Each component of Z is then transformed to a uniform random variable via the standard normal CDF and is subsequently mapped to a Gamma(4,1) random variable using the Gamma inverse CDF. This method guarantees the correct marginal Gamma distribution, while the resulting sample covariance matrix is very close to , with only small differences. An exact covariance match can be achieved using the NORTA (Normal To Anything) method, which iteratively adjusts the Gaussian correlation matrix to perfectly reproduce the target covariance after the nonlinear transformation. However, NORTA is computationally intensive, so we do not adopt it here, given that the Gaussian copula-based approach already provides sufficient accuracy and efficiency.

- : empirical distribution function based on the true errors;

- : kernel-smoothed distribution estimator based on true errors;

- : empirical distribution based on residuals (from least squares estimation);

- : kernel-smoothed distribution based on residuals (from least-squares estimation).

5. Proofs of the Main Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brockwell, P.J.; Davis, R.A. Time Series: Theory and Methods, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gut, A. Probability: A Graduate Course, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Smirnov, N.V. An approximation to distribution laws of random quantities determined by empirical data. Uspekhi Mat. Nauk. 1944, 10, 179–206. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, K.L. An estimate concerning the Kolmogorov limit distribution. Am. Math. Soc. 1949, 67, 36–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Z.W.; Roussas, G.G. Uniform strong estimation under α-mixing, with rates. Stat. Probab. Lett. 1992, 15, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamato, H. Uniform convergence of an estimator of a distribution function. Bull. Math. Statist. 1973, 15, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, F. Strong uniform consistency rates of kernel estimators of cumulative distribution functions. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 2017, 46, 6803–6807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F. Glivenko-Cantelli Theorem for the kernel error distribution estimator in the first-order autoregressive mode. Stat. Probab. Lett. 2018, 139, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F. The integrated absolute error of the kernel error distribution estimator in the first-order autoregression model. Stat. Probab. Lett. 2024, 214, 110215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Györfi, L.; Härdle, W.; Vieu, P. Nonparametric Curve Estimation from Time Series; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Roussas, G.G. Nonparametric regression estimation under mixing conditions. Stoch. Process. Their Appl. 1990, 36, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.Q.; Yao, Q.W. Nonlinear Time Series: Nonparametric and Parametric Methods; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.Y.; Liu, R.; Cheng, F.X.; Yang, L.J. Oracally efficient estimation of autoregressive error distribution with simultaneous confidence band. Ann. Statist. 2014, 42, 654–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajek, L.; Kahszka, M.; Lenic, A. The law of the iterated logarithm for Lp-norms of empirical processes. Stat. Probab. Lett. 1996, 28, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F. The law of the iterated logarithm for Lp-norms of kernel estimators of cumulative distribution functions. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.X.; Wang, J.F. The law of the iterated logarithm for positively dependent random variables. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2008, 339, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Petrov, V.V. On the law of the iterated logarithm for sequences of dependent random variables. Vestnik St. Petersb. Univ. Math. 2017, 50, 32–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, T.Z.; Zhang, Y. Law of the iterated logarithm for error density estimators in nonlinear autoregressive models. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 2019, 49, 1082–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.L. LIL for kernel estimator of error distribution in regression model. J. Korean Math. Soc. 2007, 44, 1082–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F. A law of the iterated logarithm for error density estimator in censored linear regression. J. Nonparametr. Stat. 2022, 34, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Mao, M.; Hu, X.; He, T. The Law of Iterated Logarithm for Autoregressive Processes. Math. Probl. Eng. 2014, 2014, 972712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doukhan, P.; Louhichi, S. A new weak dependence condition and applications to moment inequalities. Stochastic Processes Appl. 1999, 84, 312–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Racine, J.S. Nonparametric Econometrics: Theory and Practice; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Koul, H.L.; Zhu, Z.W. Bahadur-Kiefer representations for M-estimators in autoregression models. Stochastic Process. Appl. 1995, 57, 167–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Yang, W.Z.; Wu, S.P.; Yu, W. Asymptotic normality of residual density estimator in stationary and explosive autoregressive models. Comput. Stat. Data An. 2022, 175, 107549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.P.; Yang, W.Z.; Gao, M.; Fang, H.Y. Asymptotic results of error density estimator in nonlinear autoregressive models. J. Korean Stat. Soc. 2024, 53, 563–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csörgo, M.; Révész, P. Strong Approximation in Probability and Statistics; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, R.M. On the asymptotic eigenvalue distribution of Toeplitz matrices. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1972, 18, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withers, C.S. Conditions for linear processes to be strong-mixing. Z. Wahrscheinlichkeitstheorie Verw. Gebiete 1981, 57, 477–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P.; Heyde, C.C. Martingale Limit Theory and Its Application; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Liebscher, E. Estimation of the density and the regression function under mixing conditions. Stat. Decis. 2001, 19, 9–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.G. Fundamentals of Modern Probability Theory; Fudan University Press: Shanghai, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.T. Asymptotic theory for partly linear models. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 1995, 24, 1985–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.Q.; You, J.H.; Chen, G.M.; Zhou, X. Convergence rates of estimators in partial linear regression models with MA(∞) error process. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 2002, 31, 2251–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.Y.; Mammitzsch, V.; Steinebach, J. On a semiparametric regression model whose errors form a linear process with negatively associated innovations. Statistics 2006, 40, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhompongsa, S. A note on the almost sure approximation of the empirical process of weakly dependent random vectors. Yokohama Math. J. 1984, 32, 113–121. [Google Scholar]

- Mitrinovic, D.S. Analytic Inequalities; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, B.; Jin, Y.; Wang, L.; Shi, X.; Yang, W. The Law of the Iterated Logarithm for the Error Distribution Estimator in First-Order Autoregressive Models. Axioms 2025, 14, 784. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms14110784

Wang B, Jin Y, Wang L, Shi X, Yang W. The Law of the Iterated Logarithm for the Error Distribution Estimator in First-Order Autoregressive Models. Axioms. 2025; 14(11):784. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms14110784

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Bing, Yi Jin, Lina Wang, Xiaoping Shi, and Wenzhi Yang. 2025. "The Law of the Iterated Logarithm for the Error Distribution Estimator in First-Order Autoregressive Models" Axioms 14, no. 11: 784. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms14110784

APA StyleWang, B., Jin, Y., Wang, L., Shi, X., & Yang, W. (2025). The Law of the Iterated Logarithm for the Error Distribution Estimator in First-Order Autoregressive Models. Axioms, 14(11), 784. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms14110784