Stochastic Production Planning in Manufacturing Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Modeling feasible operating states as a smooth convex domain encoding joint capacity and safety limits, with an endogenous stopping rule that halts operations upon exit. This captures the economic reality that temporary shutdowns are preferable to uncontrolled excursions.

- Deriving the Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman (HJB) equation for a quadratic-effort plus holding-cost objective and proving the existence and uniqueness of the associated value function. The quadratic effort term represents the convex marginal costs of production adjustment, while the holding cost reflects the inventory risk.

- Establishing a concavity property of a transformed value function, which implies a robust gradient-based optimal feedback control that is well-suited to noisy environments and ensures monotone responses to shocks.

- Designing finite-difference solvers for one- and two-dimensional domains and demonstrating how the numerical policies guide operations in two application-inspired settings: (i) single-product process control and (ii) a two-variable semiconductor example with a joint safety envelope.

- (i)

- In process industries, operators must balance production rates against inventory holding risks under process noise.

- (ii)

- In semiconductor fabrication, chemical exposure and tool utilization must be simultaneously contained within a safety envelope to avoid defects or shutdowns.

2. Generalized Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman Equation

- Production configurations: is a convex, open, and bounded domain representing the set of admissible production configurations, and is a chosen interior reference point. The smooth boundary encodes the joint capacity and safety limits of the manufacturing system. Economically, represents the feasible region of operations, while marks the onset of shutdowns, quality failures, or regulatory violations.

- Inventory dynamics: The inventory levels evolve according towhere is the production-rate vector, and captures random fluctuations in the manufacturing process. In practice, reflects the non-negativity of production rates, a natural operational constraint.

- Cost functional: The objective is to minimize the total expected costwhere is a continuous inventory holding cost, and denotes the Euclidean norm. The quadratic effort term models the convex marginal costs of adjusting production, while captures the economic penalty of carrying inventory (e.g., storage, obsolescence, or capital costs).

- Stopping condition: Production halts at the stopping timewhere is the Euclidean distance between the reference point and the boundary . This condition ensures that operations are terminated before inventory trajectories leave the safe region. From a managerial viewpoint, represents the first time at which risk becomes unacceptable and a temporary halt is economically rational.

3. Results on the Value Function

3.1. Preliminaries

3.2. Existence, Uniqueness, and Positivity

3.3. Monotone Iteration (Constructive View)

3.4. Convexity and Concavity of the Transformed Value

3.5. Boundary Behavior and Gradient Asymptotics

4. Verification via Martingale Property

4.1. Definition of the Process and Hamiltonian

4.2. Itô’s Formula and Verification

4.3. Martingale and Submartingale Properties

- For any admissible p, is a submartingale.

- For , is a martingale.

4.4. Verification Inequality

4.5. Optimal Feedback Control

Summary

5. Two Examples of Numerical Implementation by Finite Difference Method

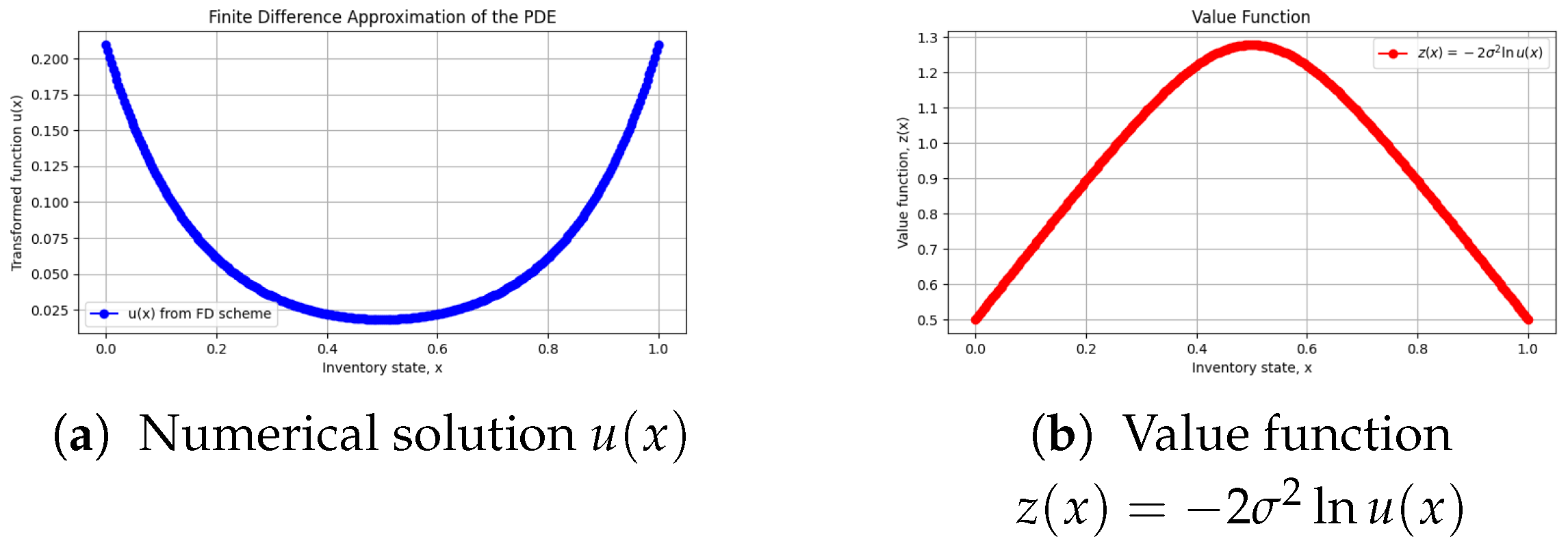

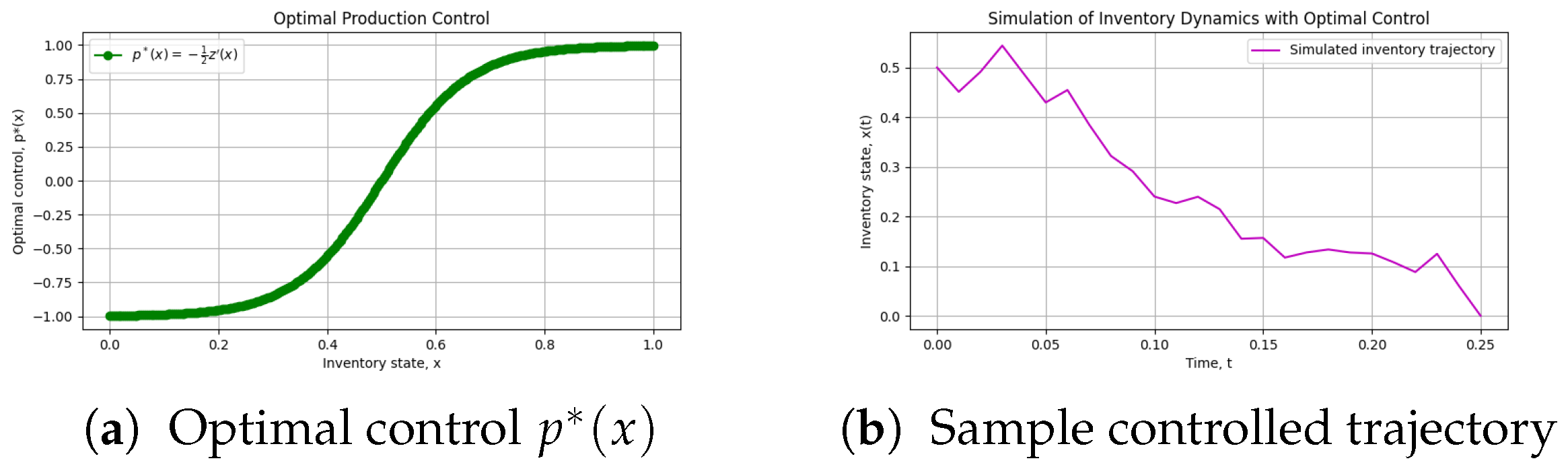

5.1. Example 1: 1D PDE on an Open Interval

5.1.1. Application Context

5.1.2. Algorithmic Outline

- Input: N (grid points), , , .

- Discretize domain with N points.

- Set boundary condition

- Formulate and solve the tridiagonal system for interior points.

- Assemble full u vector including boundaries; return .

- Compute value

- Approximate by central differences; compute

- Simulate inventory dynamics under using Euler–Maruyama with given initial state , time horizon T, and step ; halt upon exit from .

5.1.3. Numerical Results

5.1.4. Discussion

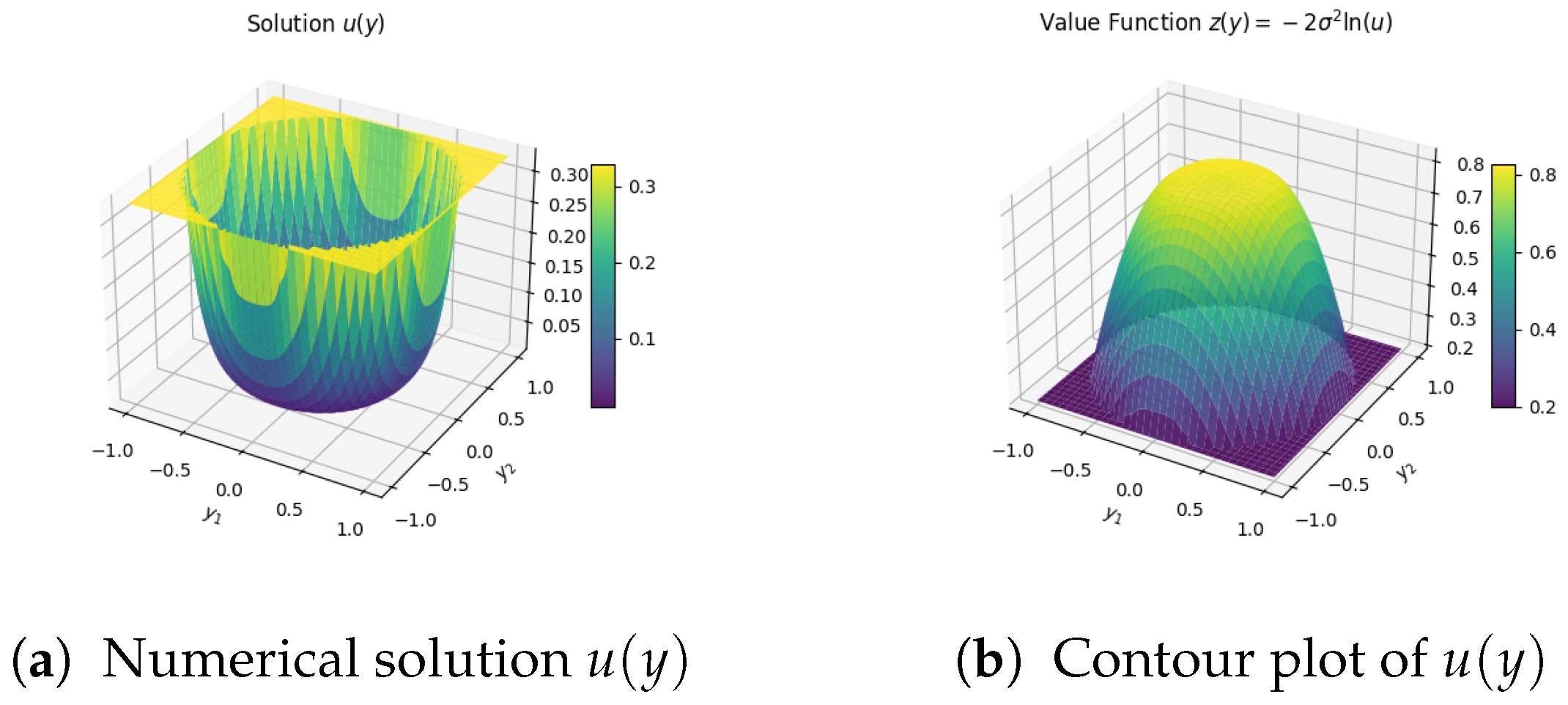

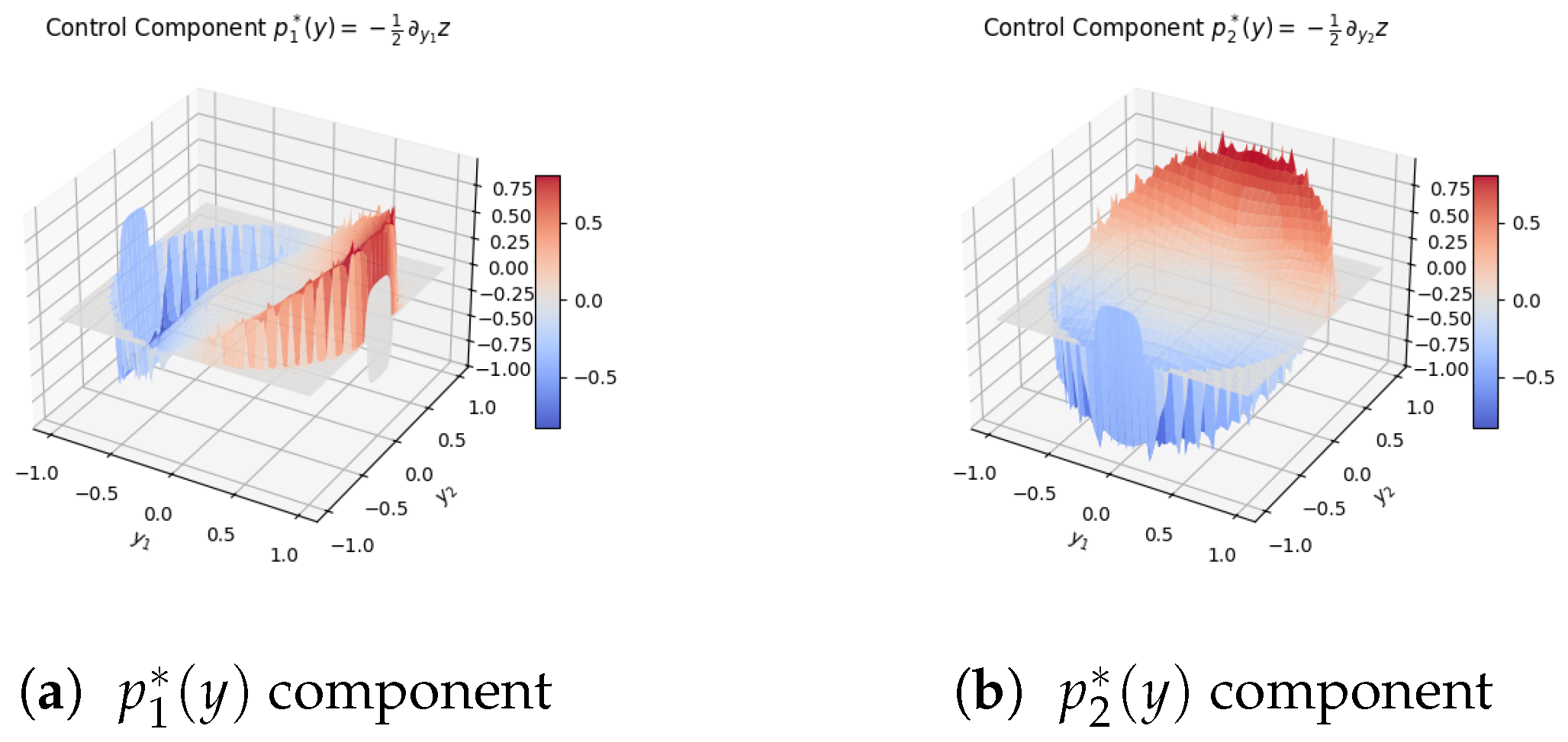

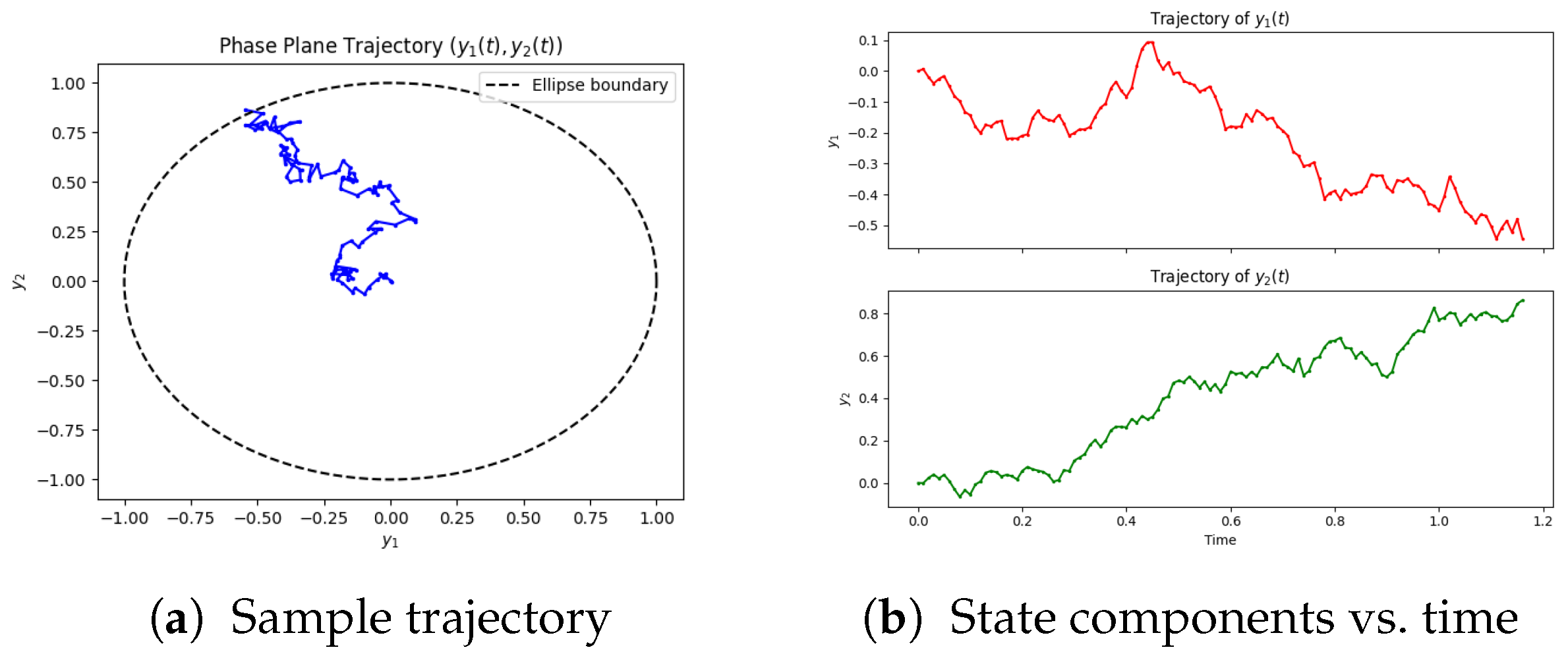

5.2. Example 2: 2D PDE on an Elliptical Domain

5.2.1. Application Context

5.2.2. Algorithmic Outline

- Input: ellipse semi-axes , volatility , terminal cost , grid spacing h, tolerance tol, maximum iterations max_iter.

- Output: meshgrid , solution , value function , controls .

- Discretize the bounding rectangle and mark interior points satisfying

- Impose Dirichlet boundary condition

- Initialize u in the interior; define

- Iterate Gauss-Seidel updates on interior points until convergence.

- Compute

- Approximate and by centered differences.

- Set

5.2.3. Numerical Results

5.2.4. Discussion

- Joint safety constraints (ellipse) lead to different corrective patterns than independent per-variable bounds.

- Concavity of z ensures that feedback controls avoid oscillations, providing robustness against noise.

- The reference point acts as the nominal safe operating point; sensitivity analysis indicates that shifting changes the stopping time and total cost , highlighting its importance in practice. Mathematically, the stopping condition corresponds to the inventory level y exiting the admissible domain . In our implementation, this condition is imposed primarily to ensure numerical tractability within the Python-based finite-difference scheme.

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

6.1. Managerial Interpretation

6.2. Role of the Stopping Rule

- Risk management. Exiting the safe-operating set triggers a halt, preventing overloads, quality failures, or regulatory breaches.

- Well-posedness and finite cost. With production halted at , the costremains finite, enabling rigorous HJB analysis and reliable numerics.

- Geometry-aware control design. The control law accounts for joint capacity constraints encoded by , avoiding operating regimes where the model or process becomes unreliable.

- Practical alignment. The exit policy formalizes standard operating procedures: intervene early, halt safely when necessary, and resume after corrective measures.

6.3. Limitations and Extensions

- Richer economics. Incorporate demand and backlog dynamics, service levels, and capacity adjustment or setup costs; consider risk-sensitive criteria (e.g., CVaR).

- General domains and constraints. Address nonconvex or time-varying feasible sets, soft constraints, reflecting boundaries, or state-dependent volatility and coupling.

- Partial information and learning. Study noisy state observations, parameter uncertainty, and data-driven estimation of ; integrate robust or adaptive control.

- High-dimensional numerics. Develop scalable solvers (FEM, multigrid, domain decomposition, policy iteration), and explore machine-learning PDE solvers (e.g., deep Galerkin methods, PINNs) for complex geometries.

- Model predictive control (MPC). Combine the HJB-based policy with receding-horizon optimization for disturbance rejection and constraint handling on plant-floor timescales.

6.4. Closing Statement

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Python Code Example 1

Appendix A.2. Python Code Example 2

References

- Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Guo, J. The Role of Longevity-Indexed Bond in Risk Management of Aggregated Defined Benefit Pension Scheme. Risks 2024, 12, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covei, D.-P. Image Restoration via Integration of Optimal Control Techniques and the Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman Equation. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Li, X.; Wang, Q. Mean-Field Stochastic Linear Quadratic Optimal Control for Jump-Diffusion Systems with Hybrid Disturbances. Symmetry 2024, 16, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharbi, A.; Kenné, J.-P.; Takengny, A.L.K.; Assid, M. Joint Emission-Dependent Optimal Production and Preventive Maintenance Policies of a Deteriorating Manufacturing System. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenné, J.-P.; Gharbi, A.; Takengny, A.L.K.; Assid, M. Optimal Control Policy of Unreliable Production Systems Generating Greenhouse Gas Emission. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kováts, P.; Skapinyecz, R. A Combined Capacity Planning and Simulation Approach for the Optimization of AGV Systems in Complex Production Logistics Environments. Logistics 2024, 8, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadenillas, A.; Lakner, P.; Pinedo, M. Optimal control of a mean-reverting inventory. Oper. Res. 2010, 58, 1697–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadenillas, A.; Lakner, P.; Pinedo, M. Optimal production management when demand depends on the business cycle. Oper. Res. 2013, 61, 1046–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharbi, A.; Kenne, J.P. Optimal production control problem in stochastic multiple-product multiple-machine manufacturing systems. IIE Trans. 2003, 35, 941–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, S.P.; Thompson, G.L. Applied Optimal Control: Applications to Management Science; Nijhoff: Boston, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, G.L.; Sethi, S.P.; Teng, J. Strong planning and forecast horizons for a model with simultaneous price and production decisions. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1984, 16, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, O. A quasilinear elliptic equation in . Proc. R. Soc. Edinb. Sect. A 1996, 126, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasry, J.M.; Lions, P.L. Nonlinear elliptic equations with singular boundary conditions and stochastic control with state constraints. Math. Ann. 1989, 283, 583–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbarg, D.; Trudinger, N.S. Elliptic Partial Differential Equations of Second Order; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Amann, H. Fixed Point Equations and Nonlinear Eigenvalue Problems in Ordered Banach Spaces. SIAM Rev. 1976, 18, 620–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, G.M. Asymptotic Behavior and Uniqueness of Blow-up Solutions of Quasilinear Elliptic Equations. J. Anal. Math. 2011, 115, 213–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, G.M. Gradient estimates for singular fully nonlinear elliptic equations. Nonlinear Anal. 2015, 119, 382–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, G.M. Gradient estimates for elliptic oblique derivative problems via the maximum principle. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2020, 25, 709–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covei, D.-P. Stochastic Production Planning: Optimal Control and Analytical Insights. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.12341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brascamp, H.J.; Lieb, E.H. On extensions of the Brunn–Minkowski and Prékopa–Leindler theorems, including inequalities for log concave functions, and with an application to the diffusion equation. J. Funct. Anal. 1976, 22, 366–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korevaar, N. Convex solutions of nonlinear elliptic and parabolic boundary value problems. Indiana Univ. Math. J. 1987, 36, 687–704. [Google Scholar]

- Canepa, E.C.; Covei, D.-P.; Pirvu, T.A. A stochastic production planning problem. Fixed Point Theory 2022, 23, 179–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloeden, P.E.; Platen, E. Numerical Solutions of Stochastic Differential Equations; Applications of Mathematics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1992; Volume 23. [Google Scholar]

- Talay, D.; Tubaro, L. Expansion of the Global Error for Numerical Schemes Solving Stochastic Differential Equations. Stoch. Anal. Appl. 1990, 8, 483–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, C. Discretization of SDEs: Euler Methods and Beyond. 2006. Available online: https://wias-berlin.de/people/bayerc/files/euler_talk_handout.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Bayram, M.; Partal, T.; Buyukoz, G.O. Numerical methods for simulation of stochastic differential equations. Adv. Contin. Discret. Model. 2018, 2018, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes-Cerfon, M. Applied Stochastic Analysis; American Mathematical Society, Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences at New York University: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Volume 33. [Google Scholar]

| Symbol | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| Volatility of production/inventory dynamics (process noise). | |

| Terminal cost upon exit (shutdown/reconfiguration penalty). | |

| Inventory holding cost; here quadratic, reflecting convex growth of storage risk. | |

| x | Inventory state (normalized to lie in ). |

| Initial inventory level (reference point for simulations). |

| Symbol | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| Normalized chemical concentration (safe range –). | |

| Normalized equipment utilization rate (safe range –). | |

| Elliptical safe-operating region capturing joint constraints. | |

| Process noise intensity (variability in both ). | |

| Shutdown/reconfiguration penalty (economic cost of exit). | |

| Reference operating point (nominal safe target, here ). | |

| Holding cost , penalizing deviations from . |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Covei, D.-P. Stochastic Production Planning in Manufacturing Systems. Axioms 2025, 14, 766. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms14100766

Covei D-P. Stochastic Production Planning in Manufacturing Systems. Axioms. 2025; 14(10):766. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms14100766

Chicago/Turabian StyleCovei, Dragos-Patru. 2025. "Stochastic Production Planning in Manufacturing Systems" Axioms 14, no. 10: 766. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms14100766

APA StyleCovei, D.-P. (2025). Stochastic Production Planning in Manufacturing Systems. Axioms, 14(10), 766. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms14100766