Abstract

One of the important issues in evaluating an interconnection network is to study the hamiltonian cycle embedding problems. A graph G is spanning k-edge-cyclable if for any k independent edges of G, there exist k vertex-disjoint cycles in G such that and for all . According to the definition, the problem of finding hamiltonian cycle focuses on . The notion of spanning edge-cyclability can be applied to the problem of identifying faulty links and other related issues in interconnection networks. In this paper, we prove that the n-dimensional hypercube is spanning k-edge-cyclable for and . This is the best possible result, in the sense that the n-dimensional hypercube is not spanning n-edge-cyclable.

MSC:

05C45

1. Introduction

Graph theory is a very important branch of discrete mathematics, and it mainly takes graph as the research object. This kind of graph is a mathematical model, using a graph as a model to represent the relationship between the real world, using the vertices of the graph to represent concrete things, and connecting the edges between the two vertices to indicate that there is a certain relationship between the two things. Graph theory is also applied to the many field such as chemistry, electrical, neural network and so on. Lu et al. used fuzzy molecular graphs to model chemical molecular structures with uncertainty information, where the vertex membership function and edge membership function describe the uncertainty of atoms and chemical bonds respectively [1]. In [2], Wang et al. used the relevant theories of graph theory to construct the electrical equipment control relations matrix of process enterprises based on analyzing the characteristics of electrical equipment faults and control relations. Li et al. proposed an ST-GCN based on node attention (NA-STGCN), so as to solve the problem of insufficient global information in ST-GCN by introducing node attention module to explicitly model the interdependence between global nodes [3]. Wang et al. focused on the research of industrial internet of things and power grid technology based on the knowledge graph and data asset relationship model [4]. Sun et al. proposed a semantic search KGSS algorithm based on the knowledge graph to explore the value of data resources of power grid enterprises [5].

In this paper, we study the architecture of an interconnection network which is always represented by a graph, where vertices represent processors and edges represent links between processors.

In recent years, the problem of embeddings in interconnection networks has attracted many researchers’ interest, especially the hamiltonian cycle and path embeddings [6,7]. Many parallel algorithms on hamiltonian cycles and paths are designed to solve various graph problems, algebraic problems, and problems in image and signal processing [8]. Consequently, embedding hamiltonian cycles (paths) into a network topology is crucial for the network simulation [9]. Thus, hamiltonicity and many variations on it have been widely studied, such as k-ordered hamiltonicity [10], hamiltonian decomposition [11], pancyclicity [12], spanning connectivity [13], and 2-factors (a 2-factor of a graph G is a spanning 2-regular subgraph of G) [14].

A graph G is Hamiltonian if it contains a Hamiltonian cycle, that is, a cycle containing all vertices of G. Let be a bipartite graph with bipartition W and B, then H is regarded as hamiltonian laceable if for any pair of vertices and , there exists a hamiltonian path , i.e., a path containing all vertices of G, between w and b. In this paper, we study the spanning-edge-cyclability of the hypercube which is a strengthen of the hamiltonian property. We allow the graph to be spanned by a prescribed number of disjoint cycles. However, each must contain a prescribed edge. This concept can be applied to the problem of identifying faulty links and other related issues in interconnection networks. A graph G is spanning k-edge cyclable if for any k independent edges of G, there are k vertex disjoint cycles such that the union of these cycles cover and each cylce contains exactly one edge. Blow, we give an example to clarify the notion.

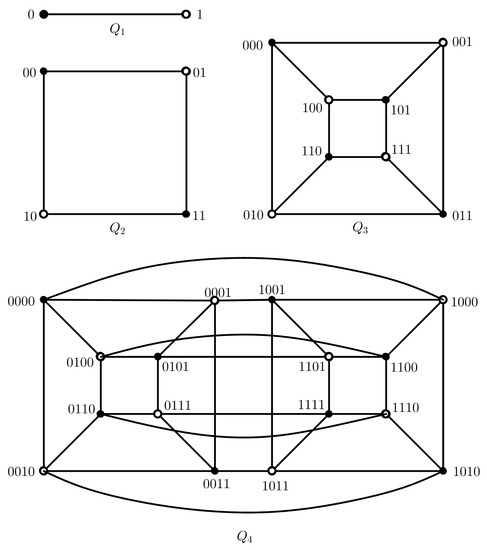

Taking 3-dimentional hypercube in Figure 1 as an example, we assume that and . We set and when ; we set and when . Then and are two disjoint spanning cycles of .

Figure 1.

The hypercubes , , and .

Wang proposed the following conjecture.

Conjecture 1

([15]). For each integer , there exists such that if G is a graph of order and for each pair of nonadjacent vertices x and y of G, then G is spanning k-edge cyclable.

The conjecture was solved by Egawa et al. in [16]. Wang also posed the bipartite version of Conjecture 1, and the conjecture is partially solved by the author.

Conjecture 2

([17]). For each integer , there exists such that if is a bipartite graph with and for each pair of non-adjacent vertices x and y of G with and , then G is spanning k-edge cyclable.

Recently, many researchers investigated the spanning cycles in a graph which contains prescribed vertices. Chronologically, in [18,19], the authors independently provided minimum degree sufficient conditions for a graph to be spanning k-cyclable. The problem of spanning k-cyclability of general graphs is well studied in the literature, see the survey article [20,21]. Besides, there are some results on spanning cyclability of special graph families. Lin et al. proved that the hypercube with is spanning k-cyclable for [14], and Kung et al. showed that the crossed cube is spanning k-cyclable for [22]. Shinde and Borse proved that the n-dimensional tori is spanning k-cyclable for [23]. Yang and Hsu proved that the generalized Petersen graph is spanning 2-cyclable for [24]. Recently, Qiao et al. proved that the enhanced hypercube with is spanning k-cyclable for and with is spanning k-cyclable for [9]. Qiao et al. also proved that Cayley graph is spanning k-cyclable if and [25]. But up to date, no one has done anything about the spanning-edge-cyclability of specified networks. So it is reasonable and important to study the spanning-edge-cyclability of interconenction networks.

The hypercube is one of the most popular and efficient interconnection networks. It possesses many excellent properties such as recursive structure, symmetry, small diameter, low degree, popular topological structure embedding, and easy routing. Because of such attractive properties, numerous topological properties of hypercubes have been extensively explored [26,27,28,29,30].

In this paper, we focus on the embedding spanning disjoint cycles in hypercubes with each cycle contains a prescribed edge. The main result of the paper is following:

Theorem 1.

The n-dimensional hypercube is spanning r-edge-cyclable for and .

2. Preliminaries

First, we give the definition of spanning k-edge-cyclable graph as follows.

Definition 1

([15]). Let k be any positive integer, a graph G is called spanning k-edge-cyclable if, for any k independent edges , there exist k vertex-disjoint cycles in G such that

- (1)

- , and

- (2)

- for all .

In Definition 1, if then G is hamiltonian laceable. Thus, the spanning cycleability of a graph is a natural extension of hamiltonicity.

We use and to denote a path and a cycle, respectively. Let be a bipartite graph with bipartition W and B. Then G is if it contains a hamiltonian cycle, i.e., a cycle containing all vertices of G. Moreover, G is regarded as hamiltonian laceable if for any pair of vertices and , there exists a hamiltonian path , i.e., a path containing all vertices of G, between w and b.

Let n be a positive integer. The n-dimensional hypercube is a graph with vertices, and its any vertex v is denoted by a unique n-bit binary string , where for . Two vertices of are adjacent if and only if their binary strings differ in exactly one bit position. It is easy to show that is an n-regular bipartite graph. Let B and W denote the two partite sets of . Assume that is an edge of . If the two binary strings of u and v differ in the i-th bit position, then the edge is called an edge of dimension i in . The set of all edges of dimension i in is denoted by . For any given h with , let and be two -dimensional subcubes of induced by all vertices with the h-th bit being 0 and 1, respectively. By removing , is divided into and , denoted by . For a given , if v is a vertex of , then there is exactly one corresponding vertex in , denoted by , such that . is an n-connected Cayley graph and hence vertex-transitive, and also edge-transitive [31]. Examples of the hypercubes , , and are illustrated in Figure 1.

For any vertex with or 1 and , let be the copy vertex of v in such that v and differ in the h-th coordinate. Let be a path in , the copy path of P in is denoted by . Similarly, let be the cycle in with or 1 and , the copy cycle of in is defined by . And denotes the length of a cycle C.

The following are the related properties of the hypercube .

Lemma 1

([27]). Let be the n-dimensional hypercube with bipartition W and B, and let be a set of all the end vertices of t independent edges in , where . Then the graph is hamiltonian. Moreover, if , then is hamiltonian laceable.

Lemma 2

([32]). Let n be any positive integer with . Let W and B form the bipartition of . Assume that x and w are any two different vertices in W, whereas y and b are any two different vertices in B. Then there exists a hamiltonian path of joining x and y.

3. Proof of the Main Result

It is obvious that the 2-dimensional hypercube is hamiltonian and the hamiltonian cycle contains every edge of . Thus is spanning 1-edge-cyclable.

Lemma 3.

The 3-dimensional hypercube is spanning t-edge-cyclable for .

Proof.

Firstly, we will prove that is spanning 1-edge-cyclable. By Lemma 1, is hamilton laceable, thus for any edge of , there exists a hamiltonian path between two end vertices u and v of the edge . Then, there exists a hamiltonian cycle containing the edge . Thus is spanning 1-edge-cyclable.

Next, we will prove that is spanning 2-edge-cyclable. Because is edge-transitive, we can fix one of the two prescribed edges as . Then we can construct desired cycles as following, see Table 1. □

Table 1.

Spanning disjoint cycles in .

Lemma 4.

The 4-dimensional hypercube is spanning t-edge-cyclable for .

Proof.

By the hamiltonian laceability of , we can directly conclude that is spanning 1-edge-cyclable. Thus, in the following, we only need to prove that is spanning t-edge-cyclable for . Note that one can divide into two 3-dimensional hypercubes and for .

Claim 1 The 4-dimensional hypercubes is spanning 2-edge-cyclable.

We may suppose that and are any two independent edges in .

- (1)

- and are in different ’s for and .

We may suppose that and . By Lemma 3, and are spanning 1-edge-cyclable, respectively. Thus, there exist two cycles and in and , respectively, where contains , contains and spans , spans . Then, spans and each cycle contains exactly one of and .

- (2)

- and are in the same for and .

We may suppose that both of and are in . By Lemma 3, is spanning 2-edge-cyclable. Thus there exist two cycles and in such that contains , contains and spans . Since is triangle free, we can choose two adjacent vertices except on . After removing the edge , the cycle becomes a path which is between and and contains . Moreover, we can take the neighbors of , respectively. By definition of , . Furthermore, by the hamiltonian laceability of , there exists a hamiltonian path between and in . Then we can construct two disjoint cycles as follows:

Clearly, spans and contains for .

Claim 2 The 4-dimensional hypercubes is spanning 3-edge-cyclable.

Let , and be three independent edges edges in .

- (1)

- Three prescribed edges , and are not in the same for .

We may suppose that and . By Lemma 3, is spanning 2-edge-cyclable. Thus, there exist two cycles and in such that spans and contains for . By Lemma 1, is hamiltonian laceable, thus there exists a hamiltonian path between and in . Then we can construct three disjoint cycles as follows:

Then spans and with .

- (2)

- Three prescribed edges , and are in the same with .

We may suppose that , and are in . Because is edge-transitive, we can fix one of the three prescribed edges , and as . Then we finish the remaining proof by brute force and the details can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

Spanning disjoint cycles in .

Combining Claims 1 and 2, the lemma follows. □

Proof of Theorem 1.

We prove the theorem by induction on n.

Base case As mentioned above, the theorem clearly holds for , and for by Lemmas 3 and 4, resectively.

Induction hypothesis Assume that is spanning r-edge-cyclable for and .

Inductive step Let be a set of r independent edges of for .

Note that can be divided into two ()-dimensional hypercubes and for some h with . Assume that for .

Case 1. .

Case 1.1. .

We may suppose that and . By induction hypothesis, is spanning r-edge-cyclable for . Thus, there exist s disjoint cycles in such that the union of spans and with . Again by induction hypothesis, there also exist disjoint cycles in such that the union of spans and with . Therefore, spans and with .

Case 1.2. .

Set . By induction hypothesis, is spanning r-edge-cyclable for . Thus, there exist r disjoint cycles in such that the union of spans and with . Then we can choose two adjacent vertices except from on . After removing the edge , the cycle becomes a path which containing is between and . Moreover, we respectively can take neighbors and of and in . By Lemma 1, is hamiltonian laceable for , thus there exists a hamiltonian path between and in . Then we can construct r disjoint cycles as follows:

Thus spans and with .

Case 2. .

Case 2.1. .

This case is similar to Case 1.1.

Case 2.2. .

Set . By induction hypothesis, is spanning -edge cyclable. Thus, there exist disjoint cycles in such that the union of spans and each of them contains exactly one edge of . Without lose of generality, we can suppose that for .

Case 2.2.1. and are in the same .

- (1)

- with .

We may suppose that . We can take neighbors of and , respectively. After removing , the cycle becomes a path containing the edge . Furthermore, we can take the neighbors , , and of a, b, and in , respectively. By Lemma 2, there exists a hamiltonian path between and in . Then we can construct disjoint cycles as follows:

Then spans and with .

- (2)

- with .

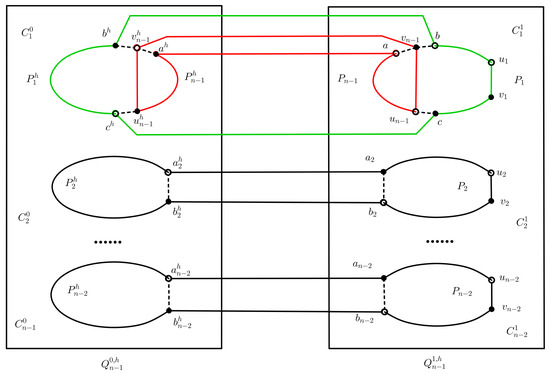

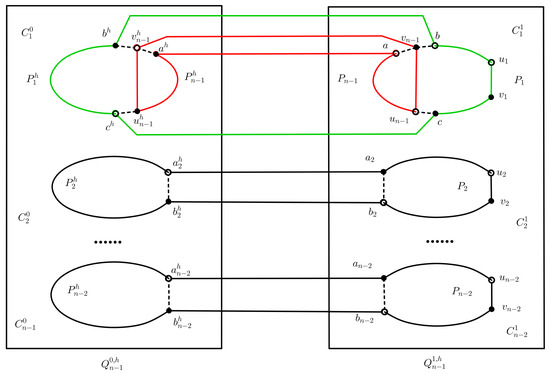

We may suppose that and . Note that there exist copy cycles in of , respectively. In this situation, and there exist other vertices between and . And then we may take neighbors a and b of , where a is between and , b is between and . We also may take a neighbor c of , where c is between and . Let be a path joining b and c which contains and be a path joining and a. Furthermore, we may take the neighbors , , , and in of , , a, b and c, respectively. Let and be two paths between and , respectively. Thus we can construct two cycles and by using the vertices of and such that with . For , we may take a pair of adjacent vertices and on except and . After removing the edge , the cycle becomes a path which contains and joins and . We also may take neighbors and in of and , respectively. Moreover, after removing the edge , the cycle becomes a path between and . Thus we can construct disjoint cycles as follows (Figure 2):

Figure 2.

Illustration of Case 2.2.1 (2).

Then spans and with .

Case 2.2.2. and are in different ’s.

We may suppose that and . Let and be neighbors of in . Similarly, let and be neighbors of in . After removing and , the cycles and become two paths and , where joins and , joins and . By definition of , there exist copy cycles in of , respectively. Further, there exist copy vertices , , , , and of , , , , and , respectively. After removing and , the cycles and become two paths and , where joins and , joins and . For , the method of constructing cycles ’s with is similar to Case 2.2.1 (2). Thus we can construct disjoint cycles as follows:

Then spans and with . □

4. Discussion

Theorem 1 is optimal, i.e., is not spanning n-edge cyclable. To see this, let u be any vertex of , and let be the set of vertices adjacent to u. Set be the n prescribed edges. If we can find n disjoint cycles such that each cycle contains exactly one edge of , then cannot contains u. Thus is not spanning n-edge-cyclable.

5. Conclusions

Embedding cycles into a network is crucial for the network simulation. Especially, in designing effective interconnection networks, embedding hamiltonian cycles is a major requirement. This study investigates the spanning edge-cyclability problem (enhanced version of the hamiltonian problem) in the hypercube . We determine that the n-dimensional hypercube is spanning r-edge-cyclable if and .

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S.; methodology, W.W. and E.S.; validation, W.W.; formal analysis, W.W.; data curation, W.W.; writing—original draft preparation, W.W.; supervision, E.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Natural Science Foundation of Xinjiang, China grant number 2021D01C116 and National Natural Science Foundation of China grant number 12261085.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the editor and anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and constructive suggestions on the original manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Lu, J.; Zhu, L.; Gao, W. Remarks on bipolar cubic fuzzy graphs and its chemical applications. Int. J. Math. Comput. Eng. 2023, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, F.; Rong, B.; Zhang, H.; Alsultan, J. The Control Relationship between the Enterprise’s Electrical Equipment and Mechanical Equipment Based on Graph Theory. Appl. Math. Nonlinear Sci. 2022, 8, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wan, J.; Zhang, W.; Kweh, Q. Spatial-temporal graph neural network based on node attention. Appl. Math. Nonlinear Sci. 2022, 7, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ma, L.; Yang, Z. Research on industrial Internet of Things and power grid technology application based on knowledge graph and data asset relationship model. Appl. Math. Nonlinear Sci. 2022, 8, 2717–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Hao, T.; Li, X. Knowledge graph construction and Internet of Things optimisation for power grid data knowledge extraction. Appl. Math. Nonlinear Sci. 2022, 8, 2729–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Lin, C.-K.; Fan, J.; Jia, X. Hamiltonian cycle and path embeddings in 3-ary n-cubes based on K1,3-structure faults. J. Parallel Distr. Comput. 2018, 120, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Erickson, A.; Fan, J.; Jia, X. Hamiltonian Properties of DCell Networks. Comput. J. 2015, 58, 2944–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leighton, F.T. Introduction to Parallel Algorithms and Architecture: Arrays, Trees, Hypercubes; Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc.: Burlington, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, H.; Meng, J.; Sabir, E. Embedding spanning disjoint cycles in enhanced hypercube networks with prescribed vertices in each cycle. Appl. Math. Comput. 2022, 435, 127481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.-H.; Tan, J.J.M.; Cheng, E.; Lipták, L.; Lin, C.-K.; Tsai, M. Solution to an open problem on 4-ordered Hamiltonian graphs. Discrete Math. 2012, 312, 2356–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, J. Hamiltonian decompositions of cayley graphs on abelian groups of even order. J. Comb. Theory B 2003, 88, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, S.-Y.; Shiu, J.-Y. Cycle embedding of augmented cubes. Appl. Math. Comput. 2007, 191, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.-H.; Lin, C.-K. Graph Theory and Interconnection Networks; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-K.; Tan, J.J.M.; Hsu, L.-H.; Kung, T.-L. Disjoint cycles in hypercubes with prescribed vertices in each cycle. Discrete Appl. Math. 2013, 161, 2992–3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Covering a graph with cycles passing through given edges. J. Graph Theory 1997, 26, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egawa, Y.; Faudree, R.J.; Györi, E.; Ishigami, Y.; Schelp, R.H.; Wang, H. Vertex-disjoint cycles containing specified edges. Graphs Comb. 2000, 16, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Covering a bipartite graph with cycles passing through given edges. J. Graph Theory 1999, 19, 115–121. [Google Scholar]

- Egawa, Y.; Enomoto, H.; Faudree, R.; Li, H.; Schiermeyer, I. Two-factors each component of which contains a specified vertex. J. Graph Theory 2003, 43, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishigami, Y.; Jiang, T. Vertex-disjoint cycles containing prescribed vertices. J. Graph Theory 2003, 42, 276–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, S.; Yamashita, T. Degree conditions for the existence of vertex-disjoint cycles and paths: A Survey. Graphs Comb. 2018, 4, 1–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, R. A look at cycles containing specified elements of a graph. Discrete Math. 2009, 309, 6299–6311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kung, T.-L.; Hung, C.-N.; Lin, C.-K.; Chen, H.-C.; Lin, C.-H.; Hsu, L.-H. A framework of cycle-based clustering on the crossed cube architecture. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Innovation Mobile and Internet Services in Ubiquitous Computing, Fukuoka, Japan, 6–8 July 2016; Volume 10, pp. 430–434. [Google Scholar]

- Shinde, A.; Borse, Y.M. Disjoint cycles through prescribed vertices in multidimensional tori. J. Ramanujan Math. 2021, 4, 283–290. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.-C.; Hsu, L.-H.; Hung, C.-N.; Cheng, E. 2-spanning cyclability problems of some generalized Petersen graphs. Discuss. Math. Graph Theory 2020, 40, 713–731. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, H.; Sabir, E.; Meng, J. The spanning cyclability of Cayley graphs generated by transposition trees. Discrete Appl. Math. 2023, 328, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-H.; Jiang, S.-Y. Path bipancyclicity of hypercubes. Inf. Process. Lett. 2007, 101, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-B. Hamiltonian of hypercubes with faulty vertices. Inf. Process. Lett. 2016, 116, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.-S. Fault-tolerant cycle embedding in the hypercube. Parallel Comput. 2003, 29, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.K.; Tsai, C.H.; Tan, J.J.M.; Hsu, L.H. Bipannectivity and edge-fault-tolerant bipancyclicity of hypercubes. Inf. Process. Lett. 2003, 87, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, Y.; Schultz, M.H. Topological properties of hypercubes. IEEE Trans. Comput. 1988, 37, 867–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.-M.; Ma, M. Survey on path and cycle embedding in some networks. Front. Math. China 2009, 4, 217–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.-M.; Hung, C.-N.; Huang, H.-M.; Hsu, L.-H.; Jou, Y.-D. Hamiltonian laceability of faulty hypercubes. J. Interconnect. Netw. 2007, 8, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).