Abstract

In this paper, we construct an affine model of a Riemann surface with a flat Riemannian metric associated to a Schwarz–Christoffel mapping of the upper half plane onto a rational triangle. We explain the relation between the geodesics on this Riemann surface and billiard motions in a regular stellated n-gon in the complex plane.

MSC:

30C30; 30F10

1. Introduction

We give a section by section summary of the contents of this paper.

In §1 we define the Schwarz–Christoffel conformal map (2) of the complex plane less onto a quadrilateral Q, which is formed by reflecting a rational triangle in the real axis.

In §2, following Aurell and Itzykson [1] we associate to the map the affine Riemann surface in defined by , where has coordinates and . Thinking of as a branched covering

with branch points at , and ∞ corresponding to the branch values 0, 1, and ∞, respectively, we show that has genus , where for . Let be the set of nonsingular points of . The map is a holomorphic n-fold covering map with covering group the cyclic group generated by

In §3 we build a model of the affine Riemann surface . The quadrilateral Q is holomorphically diffeomorphic to a fundamental domain of the action of the covering group on . Rotating Q by

gives a regular stellated n-gon , which is invariant under the dihedral group G generated by the mappings R and . We study the group theoretic properties of . We show that is invariant under the reflection in the ray for . To construct the model of the affine Riemann surface from the regular stellated n-gon we follow Richens and Berry [2]. We identify two nonadjacent closed edges of , the closure of , if one edge is obtained from the other by a reflection for some . The identification space , where is the center of , is a complex manifold except at points corresponding to or a vertex of , where it has a conical singularity. The action of G on induces a free and proper action on the identification space , whose orbit space is a complex manifold with compact closure in , with genus . Moreover is holomorphically diffeomorphic to the affine Riemann surface .

In §4, we construct an affine model of the Riemann surface . In other words, we find a discrete subgroup of the 2-dimensional Euclidean group , which acts freely and properly on such that after forming an identification space the orbit space is holomorphically diffeomorphic to . We now describe the group . Reflect the regular stellated n-gon in its edges, and then in the edges of the reflected regular stellated n-gons, et cetera. We obtain a group generated by translations so that sends the center of to the center of a repeatedly reflected reflected n-gon. The set is the union of the image under of a vertex of and its center for every . Let be the semi-direct product . The fundamental domain of the action on is less its vertices and center. Identifying equivalent open edges of and then taking G orbits, it follows that the affine model of the affine Riemann surface is the orbit space .

In §5 we show that the mapping

straightens the nowhere vanishing holomorphic vector field X (11) on , that is, for every . We pull back the flat metric on by to the metric on . So is a local developing map. Since is the geodesic vector field on , it follows that X is a holomorphic geodesic vector field on .

In §6 we study the geometry of the developing map . The dihedral group generated by and is a group of isometries of . The group G generated by R and is a group of isometries of . Extend the holomorphic map to a holomorphic map map by requiring that on . This works since is a fundamental domain of the action of the covering group on , which implies . Thus, the local holomorphic diffeomorphism intertwines the action on with the G action on and intertwines the local geodesic flow of the holomorphic geodesic vector field X with the local geodesic flow of the holomorphic vector field .

Following Richens and Berry [2] we impose the condition: when a geodesic, starting at a point in , meets it undergoes a reflection in the edge of that it meets. Such geodesics never meet a vertex of . Thus, this type of geodesic becomes a billiard motion in , which is defined for all time. Billiard motions in polygons have been extensively studied. For a nice overview see Berger ([3], chpt. XI) and references therein. An argument shows that invariant geodesics on correspond under the map to billiard motions on .

Repeatedly reflecting a billiard motion in an edge of and suitable edges of suitable translations of gives a straight line motion on . The image of the segment of a billiard motion, where intersects , in the orbit space , is a geodesic. Here we use the flat Riemannian metric on , which is induced by the invariant Euclidean metric on restricted to . Consequently, is an affine analogue of the affine Riemann surface thought of as the orbit space of a discrete subgroup of acting on with the Poincaré metric, see Weyl [4].

2. A Schwarz–Christoffel Mapping

Consider the conformal Schwarz–Christoffel mapping

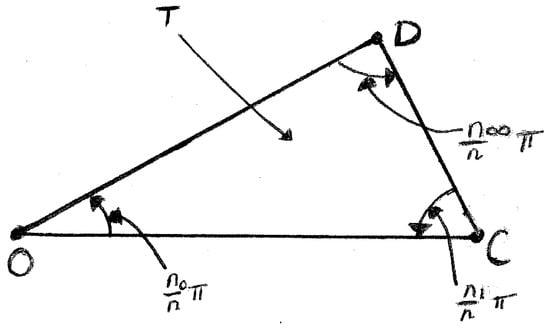

of the upper half plane to the rational triangle with interior angles , , and , see Figure 1. Here and for and ∞ with . Because is greater than or equal to either or , it follows that the corresponding side is the longest side of the triangle .

Figure 1.

The rational triangle .

In the integrand of (1) we use the following choice of complex root. Suppose that . Let and where and , . For on the real axis we have , , and . So . In general for , we have

From (1) we get

where and . Consequently, the bijective holomorphic mapping sends , the interior of the upper half plane less 0 and 1, onto , the interior of the rational triangle , and sends the boundary of to the edges of less their end points O, C and D, see Figure 1. Thus, the image of under is . Here is the closure of T in .

Because is real valued, we may use the Schwarz reflection principle to extend to the holomorphic diffeomorphism

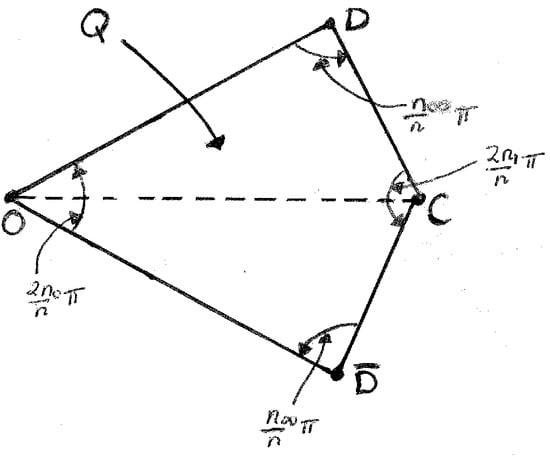

Here is a quadrilateral with internal angles , , , and and vertices at O, D, C, and , see Figure 2. The conformal mapping sends onto .

Figure 2.

The rational quadrilateral Q.

3. The Geometry of an Affine Riemann Surface

Let and be coordinate functions on . Consider the affine Riemann surface in , associated to the holomorphic mapping , defined by

see Aurell and Itzykson [1]. We determine the singular points of by solving

For , we have if and only if or . Thus, the set of singular points of is . So the affine Riemann surface is a complex submanifold of . Actually, , for if and , then either or .

Lemma 1.

Topologically is a compact Riemann surface of genus less three points: , , and . Here for .

Proof.

Consider the (projective) Riemann surface specified by the condition if and only if

Thinking of G as a polynomial in with coefficients which are polynomials in and , we may view as the branched covering

When we get the affine branched covering

From (3) it follows that , where for is an nth root of unity with and is the complex nth root used in the definition of the mapping (1). Thus, the branched covering mapping (6) has n “sheets” except at its branch points. Since

and

it follows that and are branch points of the mapping of degree and , since for , see McKean and Moll ([5], p. 39). Because

∞ is a branch point of the mapping of degree , where . Hence the ramification index of 0, 1, ∞ is , , and , respectively. Thus, the map has fewer sheets at 0, fewer at 1, and fewer at ∞ than an n-fold covering of . Thus, the total ramification index r of the mapping is . By the Riemann–Hurwitz formula, the genus g of is . In other words,

Consequently, the affine Riemann surface is the compact connected surface less the point at ∞, namely, . So is the compact connected surface less three points: , , and . □

Examples of

- , , ; . So , , . Hence . So .

- , , ; . So . Hence . So .

Table 1 below lists all the partitions of n, which give a low genus Riemann surface

Table 1.

Based on the table in Aurell and Itzykson ([1], p. 193).

Corollary 1.

If n is an odd prime number and is a partition of n into three parts, then the genus of is .

Proof.

Because n is prime, we get . Using the formula we obtain . □

Corollary 2.

The singular points of the Riemann surface are , , and if then also .

Proof.

A point if and only if , that is,

and

We need only check the points , and . Since the first two points are singular points of , they are singular points of . Thus, we need to see if is a singular point of . Substituting into the right hand side of (10b) we get Thus, is a singular point of only if . □

Lemma 2.

The mapping

is a surjective holomorphic local diffeomorphism.

Proof.

Let and let

By hypothesis implies that . The vector is defined and is nonzero. From and , it follows that . Using the definition of (12) and the definition of the mapping (7), we see that the tangent of the mapping (11) at is given by

Since and are nonzero vectors, they form a complex basis for and , respectively. Thus, the complex linear mapping is an isomorphism. Hence is a local holomorphic diffeomorphism. □

Corollary 3.

(11) is a surjective holomorphic n to 1 covering map.

Proof.

We only need to show that is a covering map. First we note that every fiber of is a finite set with n elements, since for each fixed we have . Here for , is an root of 1 and is the complex root used in the definition of the Schwarz–Christoffel map (2). Hence the map is a proper surjective holomorphic submersion, because each fiber is compact. Thus, the mapping is a presentation of a locally trivial fiber bundle with fiber consisting of n distinct points. In other words, the map is a n to 1 covering mapping. □

Consider the group of linear transformations of generated by

Clearly , the identity element of and . For each we have

So . Thus, we have an action of on the affine Riemann surface given by

Since is finite, and hence is compact, the action is proper. For every we have and . So maps into itself. At the isotropy group is , that is, the -action on is free. Thus, the orbit space is a complex manifold.

Corollary 4.

Consider the holomorphic mapping

where is the -orbit of in . The principal bundle presented by the mapping ρ is isomorphic to the bundle presented by the mapping (11).

Proof.

We use invariant theory to determine the orbit space . The algebra of polynomials on , which are invariant under the -action , is generated by . Since , these polynomials are subject to the relation

Equation (15) defines the orbit space as a complex subvariety of . This subvariety is homeomorphic to , because it is the graph of the function . Consequently, the orbit space is holomorphically diffeomorphic to .

It remains to show that is the group of covering transformations of the bundle presented by the mapping (11). For each look at the fiber . If , then , since or and . Thus, . So . Hence . Thus, is a covering transformation for the bundle presented by the mapping . So is a subgroup of the group of covering transformations. These groups are equal because acts transitively on each fiber of the mapping . □

4. Another Model for

We construct another model for the smooth part of the affine Riemann surface (3) as follows. Let be a fundamental domain for the action (14) on . So if and only if for we have . Here is the root used in the definition of the mapping (2). The domain is a connected subset of with nonempty interior. Its image under the map (11) is . Thus, is one “sheet” of the covering map . So is one to one.

Using the extended Schwarz–Christoffel mapping (2), we give a more geometric description of the fundamental domain . Consider the mapping

where the map is given by Equation (11). The map is a holomorphic diffeomorphism of onto , which sends homeomorphically onto . Look at , which is a closed quadrilateral with vertices O, D, C, and . The set contains the open edges , , and but not the open edge of , see Figure 3 above.

Figure 3.

The image Q of the fundamental domain under the mapping . The open edges , , and of the quadrilateral are included; while the open edge is excluded.

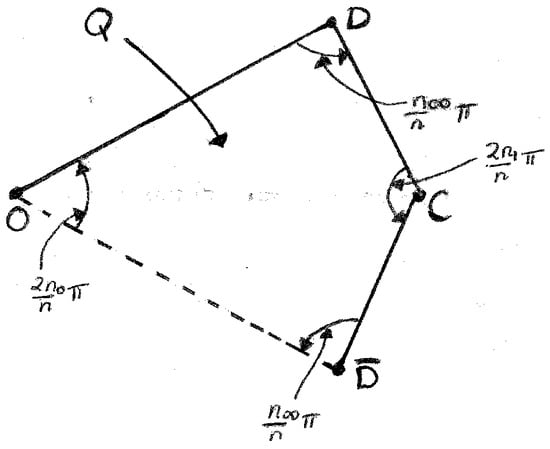

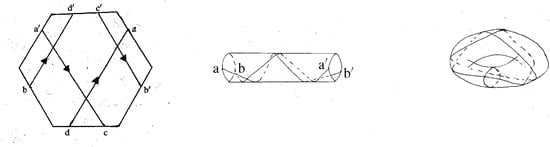

Let be the region in formed by repeatedly rotating through an angle . Here R is the rotation . We say that the quadrilateral forms, see Figure 4 above.

Figure 4.

The regular duodecagon K and the stellated regular duodecagon formed by rotating the quadrilateral through an angle 2/12 around the origin.

Theorem 1.

The connected set is a regular stellated n-gon with its vertices omitted, which is formed from the quadrilateral , see Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The dart in the figure is the quadrilateral , which is the union of the triangles and the triangle .

Proof.

By construction the quadrilateral is contained in the quadrilateral . Note that . Thus,

So . Thus, is the regular stellated n-gon less its vertices, one of whose open sides is the diagonal of . □

We would like to extend the mapping (16) to a mapping of onto . Let

where is the action defined in Equation (14). So we have a mapping

defined by . The mapping is defined on , because , since is a fundamental domain for the -action (14) on . Because , the mapping is surjective. Hence is holomorphic, since it is continuous on and is holomorphic on the dense open subset of . Let and let G be the group generated by the rotation R and the reflection U subject to the relations and . Shorthand . Then . The group G is the dihedral group . The closure of in is invariant under , the subgroup of G generated by the rotation R. Because the quadrilateral Q is invariant under the reflection , and , it follows that is invariant under the reflection U. So is invariant under the group G.

We now look at some group theoretic properties of .

Lemma 3.

If F is a closed edge of the polygon and for some , then .

Proof.

Suppose that . Then for some and some , . Let and suppose that F is an edge of such that , where . Then , but . So . Now suppose that . Then . So . Hence . Finally, suppose that with . Then . So . □

Lemma 4.

For put . Then is a reflection in the closed ray . The ray is the closure of the side of the quadrilateral in Figure 5.

Proof.

fixes every point on the closed ray , because

Since , it follows that is a reflection in the closed ray . □

Corollary 5.

For every and every let . Here , because . Then is a reflection in the closed ray .

Proof.

This follows because and fixes every point on the closed ray , for

□

Corollary 6.

For every , every with , and every , we have for a unique .

Proof.

We compute. For every we have

and

where . Since R and U generate the group G, the corollary follows. □

Corollary 7.

For let be the group generated by the reflections for . Then is a normal subgroup of G.

Proof.

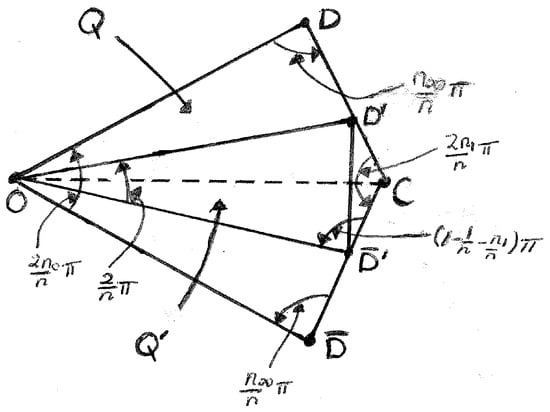

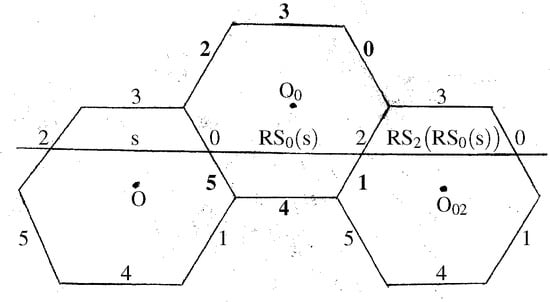

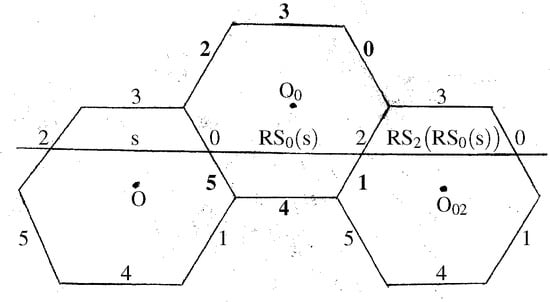

As a first step in constructing the model of from the regular stellated n-gon we look at certain pairs of edges of . For each we say two distinct closed edges E and of are adjacent if and only if they intersect at a vertex of . For let be the set of unordered pairs of equivalent closed edges E and of , that is, the edges E and are not adjacent and for some generator of . Recall that for x and y in some set, the unordered pair is precisely one of the ordered pairs or . Note that is the set of all unordered pairs of nonadjacent edges of . Geometrically, two nonadjacent closed edges and E of are equivalent if and only if is obtained from E by reflection in the line for some and some . In Figure 6, where , parallel edges of , which are labeled with the same letter, are -equivalent. This is no coincidence.

Figure 6.

The triangulation of the regular stellated hexagon . The vertices of cl() are labeled for and equivalent edges by .

Lemma 5.

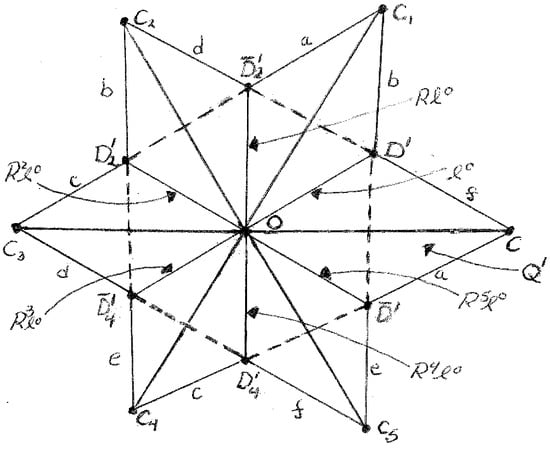

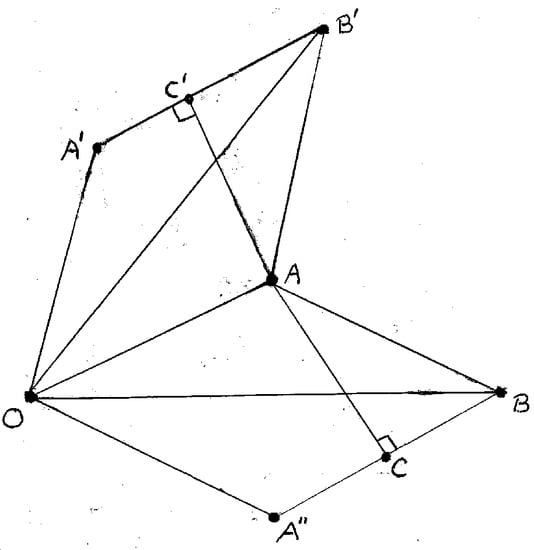

Let be formed from the quadrilateral , where T is the isosceles rational triangle less its vertices. Then nonadjacent edges of are -equivalent if and only if they are parallel, see Figure 7.

Figure 7.

The geometric configuration.

Proof.

In Figure 7, let be the triangle T with , , and . Let be the quadrilateral formed by reflecting the triangle in its edge . The quadrilateral reflected it its edge is the quadrilateral . Let be perpendicular to and be perpendicular to , see Figure 7. Then is a straight line if and only if . By construction and . So

if and only if . Hence the edges and are parallel if and only if the triangle is isosceles. □

Theorem 2.

Let be the regular stellated n-gon formed from the rational quadrilateral with for . The G orbit space formed by first identifiying equivalent edges of the regular stellated n-gon formed from Q less O and then acting on the identification space by the group G is , which is a smooth 2-sphere with g handles, where , less some points corresponding to the image of the vertices of .

Example 1.

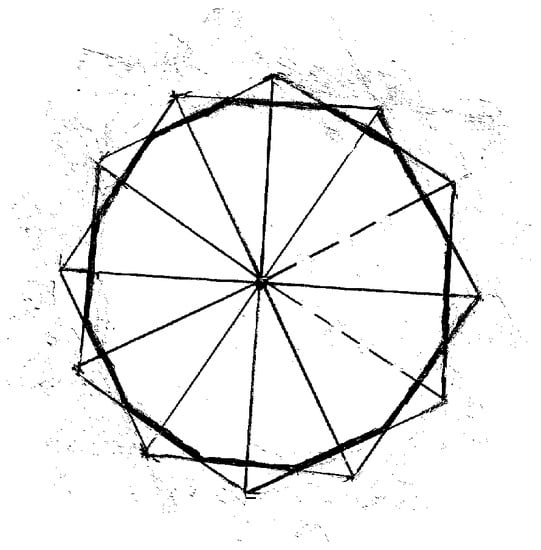

Before we begin proving Theorem 2 we consider the following special case. Let be a regular stellated hexagon formed by repeatedly rotating the quadrilateral by R through an angle , see Figure 6.

Let be the group generated by the reflections for . Here is the reflection which leaves the closed ray fixed. Define an equivalence relation on by saying that two points x and y in are equivalent, , if and only if 1) x and y lie on with x on the closed edge E and for some reflection or 2) if x and y lie in the interior of and . Let be the space of equivalence classes and let

be the identification map which sends a point to the equivalence class , which contains p. Give the topology induced from . Placing the quotient topology on turns it into a connected topological manifold without boundary, whose closure is compact. Let be less its vertices. The identification space is a connected 2-dimensional smooth manifold without boundary.

Let . The usual G-action

preserves equivalent edges of and is free on . Hence it induces a G action on , which is free and proper. Thus, its orbit map

is surjective, smooth, and open. The orbit space is a connected 2-dimensional smooth manifold. The identification space has the orientation induced from an orientation of , which comes from . So has a complex structure, since each element of G is a conformal mapping of into itself.

Our aim is to specify the topology of . The regular stellated hexagon less the origin has a triangulation made up of 12 open triangles and for ; 24 open edges , , , and for ; and 12 vertices and for , see Figure 6.

Consider the set of unordered pairs of equivalent closed edges of , that is, is the set for , where E is a closed edge of . Table 2 lists the elements of . G acts on , namely, , for . Since is the group generated by the reflections , , it is a normal subgroup of G. Hence the action of G on restricts to an action of on and the G action permutes -orbits in . Thus, the set of -orbits in is G-invariant.

Table 2.

The set . Here and for and for , see Figure 6.

We now look at the -orbits on . We compute the -orbit of as follows. We have

Since

and

the orbit of is . Here , since . Similarly, the -orbit of is . Since , we have found all -orbits on . The G-orbit of is for , since ; while the G-orbit of is , for , since .

Suppose that B is an end point of the closed edge E of . Then E lies in a unique of . Let be the -orbit of . Then is an end point of the closed edge of for every . So the -orbit of the vertex B. It follows from the classification of -orbits on that and are -orbits of the vertices of , which are permuted by the action of G on . Furthermore, and are G-orbits of vertices of , which are end points of the G-orbit of the rays and , respectively.

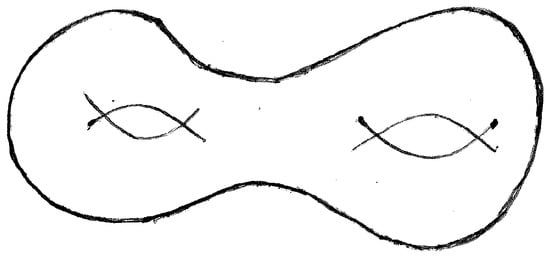

To determine the topology of the G orbit space we find a triangulation of . Note that the triangulation of , illustrated in Figure 6, is G-invariant. Its image under the identification map is a G-invariant triangulation of . After identification of equivalent edges, each vertex , each open edge , having as an end point, or each open edge , where is a pair of equivalent edges of , and each open triangle in lies in a unique G orbit. It follows that , or , and is a vertex, an open edge, and an open triangle, respectively, of a triangulation of . The triangulation has 4 vertices, corresponding to the G orbits , , , and ; 18 open edges corresponding to , , and for ; and 12 open triangles and for . Thus, the Euler characteristic of is . Since is a 2-dimensional smooth real manifold, , where g is the genus of . Hence . So is a smooth 2-sphere with 2 handles, less a finite number of points, which lies in a compact topological space , that is its closure, see Figure 8. This completes the example.

Figure 8.

The G-orbit space is 2-sphere with two handles.

Proof of Theorem 2.

We now begin the construction of by identifying equivalent edges of . For each let be an unordered pair of equivalent closed edges of . We say that x and y in are equivalent, , if 1) x and y lie in with and for some and some or 2) x and y lie in and . The relation ∼ is an equivalence relation on . Let be the set of equivalence classes and let

be the map which sends p to the equivalence class , that contains p. Compare this argument with that of Richens and Berry [2]. Give the topology induced from and put the quotient topology on . □

Theorem 3.

Let be less its vertices. Then is a smooth manifold. Furthermore, is a topological manifold.

Proof.

To show that is a smooth manifold, let be an open edge of . For let be a disk in with center at , which does not contain a vertex of . Set . For each let be an open edge of , which is equivalent to via the reflection , that is, is an unordered pair of equivalent edges. Let and set . Then is an open neighborhood of in , which is a smooth 2-disk, since the identification mapping is the identity on . It follows that is a smooth 2-dimensional manifold without boundary.

We now handle the vertices of . Let be a vertex of and set , where is a disk in with center at the vertex . The map

with and is a homeomorphism, which sends the wedge with angle to the wedge with angle . The latter wedge is formed by the closed edges and of , which are adjacent at the vertex such that with the edge being swept out through during its rotation to the edge . Because is a rational regular stellated n-gon, the value of s is a rational number for each vertex of . For each let be an edge of , which is equivalent to and set . Then is a vertex of , which is the center of the disk . Set . Then is a disk in . The map , where and , is a homeomorphism of D into a neighborhood of in . Consequently, the identification space is a topological manifold. □

We now describe a triangulation of . Let be the open rational triangle with vertex at the origin O, longest side on the real axis, and interior angles , , and . Let be the quadrilateral . Then is a subset of the quadrilateral , see Figure 5. Moreover . The triangles and with form a triangulation of with vertices and for ; open edges , , , and for ; and open triangles , with . The image of the triangulation under the identification map (21) is a triangulation of the identification space .

The action of G on preserves the set of unordered pairs of equivalent edges of for each . Hence G induces an action on , which is proper, since G is finite. The G action is free on and thus on by Lemma A2. We have proved

Lemma 6.

The G-orbit space is a compact connected topological manifold with being a smooth manifold. Let

Then σ is the G orbit map, which is surjective, continuous, and open. The restriction of σ to has image and is a smooth open mapping.

We now determine the topology of the orbit space . For each and let be an end point of a closed edge E of , which lies on the unordered pair . Then is an end point of the edge of the unordered pair of . See Appendix A for the definition of the group . The sets with are permuted by G. The action of G on preserves the set of open edges of the triangulation . There are -orbits: ; , since ; and , since for . So the image of the triangulation under the continuous open map

is a triangulation of the G-orbit space with vertices , where and ; open edges , , and for ; and open triangles and for . Thus, the Euler characteristic of is . However, is a smooth manifold. So , where g is the genus of . Hence . Compare this argument with that of Weyl ([4], p. 174). This proves Theorem 2.

Since the quadrilateral Q is a fundamental domain for the action of G on , the G orbit map restricted to Q is a bijective continuous open mapping. However, is a bijective continous open mapping of the fundamental domain of the action on . Consequently, the orbit space is homeomorphic to the G orbit space . The mapping is holomorphic except possibly at 0 and the vertices of . So the mapping is a holomorphic diffeomorphism.

5. An Affine Model of

We construct an affine model of the affine Riemann surface as follows. Return to the regular stellated n-gon , which is formed from the quadrilateral less its vertices. Repeatedly reflecting in the edges of and then in the edges of the resulting reflections of et cetera, we obtain a covering of by certain translations of . Here is the union of the translates of the vertices of and its center O. Let be the group generated by these translations. The semidirect product acts freely, properly and transitively on . It preserves equivalent edges of and it acts freely and properly on , the space formed by identifying equivalent edges in . The orbit space is holomorphically diffeomorphic to and is the desired affine model of . We now justify these assertions.

First we determine the group of translations.

Lemma 7.

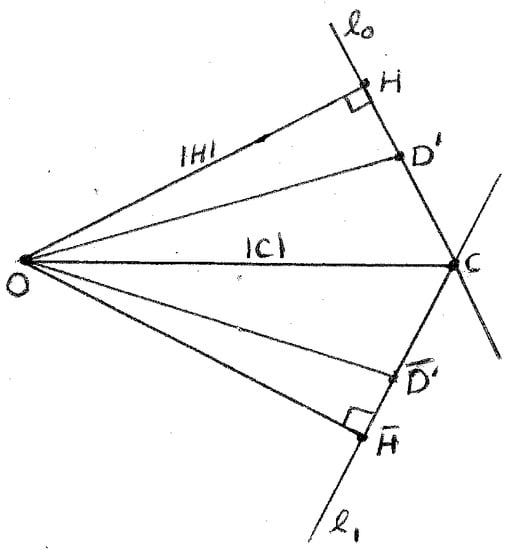

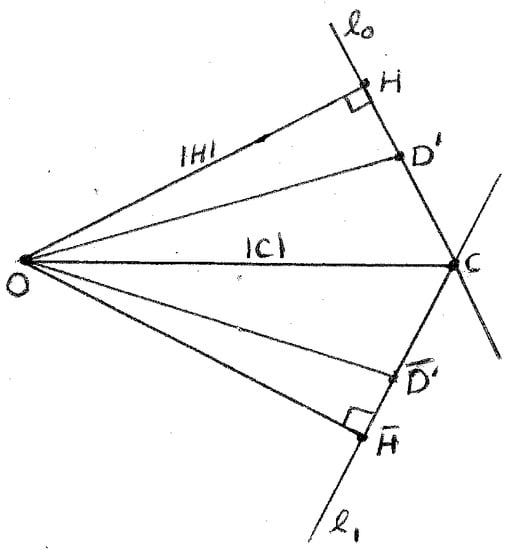

Each of the sides of the regular stellated n-gon is perpendicular to exactly one of the directions

for .

Proof.

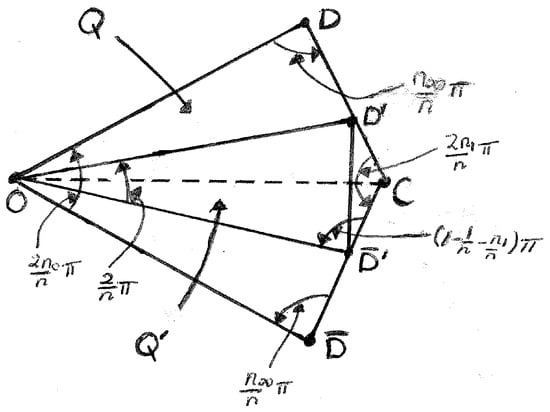

From Figure 9 we have . So . Hence the line , containing the edge of , is perpendicular to the direction . Since is the reflection of in the line segment , the line , containing the edge of , is perpendicular to the direction . Because the regular stellated n-gon is formed by repeatedly rotating the quadrilateral through an angle , we find that Equation (23) holds. □

Figure 9.

The regular stellated n-gon two of whose sides are and .

Since , it follows that is the distance from the center O of to the line containing the side , or to the line containing the side . So is the closest point H on to O and is the closest point on to O. Since the regular stellated n-gon is formed by repeatedly rotating the quadrilateral through an angle , the point

lies on the line , which contains the edge of ; while

lies on the line , which contains the edge of for every . Furthermore, the line segments and are perpendicular to the line and , respectively, for .

Corollary 8.

For we have

Corollary 9.

For k, we have

Proof.

If , then , by definition. So

If , then , by definition. So

□

For let be the translation

Corollary 10.

For k, we have

Proof.

For every , we have

□

Reflecting the regular stellated n-gon in its edge contained in gives a congruent regular stellated n-gon with the center O of becoming the center of .

Lemma 8.

The collection of all the centers of the regular stellated n-gons, formed by reflecting in its edges and then reflecting in the edges of the reflected regular stellated n-gons et cetera, is

where for we have

Proof.

For each the center of the regular stellated congruent n-gon formed by reflecting in an edge of contained in the line is . Repeating the reflecting process in each edge of gives congruent regular stellated n-gons with center at , where . Repeating this construction proves the lemma. □

Corollary 11.

The set

is the collection of vertices and centers of the congruent regular stellated n-gons , , .

Proof.

This follows immediately from Lemma 8. □

Corollary 12.

The union of , where , , and , covers , that is,

Proof.

This follows immediately from . □

Let be the abelian subgroup of the 2-dimensional Euclidean group generated by the translations (28) for . It follows from Corollary 12 that the regular stellated n-gon with its vertices and center removed is the fundamental domain for the action of the abelian group on . The group is isomorphic to the abelian subgroup of generated by .

Next we define the group and show that it acts freely, properly, and transitively on . Consider the group , which is the semidirect product of the dihedral group G, generated by the rotation R through and the reflection U subject to the relations and , and the abelian group . An element of is the affine linear map

Multiplication in is defined by

which is the composition of the affine linear map followed by . The mappings and are injective, which allows us to identify the groups G and with their image in . Using (31) we may write an element of as . So

For every we have

that is,

Hence

which is just Equation (29). The group acts on as does, namely, by affine linear orthogonal mappings. Denote this action by

Lemma 9.

The set (30) is invariant under the action.

Proof.

Let . Then for some and some

where . For with and we have

where . If , then

while if , then

Here see Corollary 8. So , which implies , as desired. □

Lemma 10.

The action of on is free.

Proof.

Suppose that for some and some we have . Then v lies in some . So for some we have

where for some . Thus,

This implies , that is, . So , that is, . Hence , which is the identity element of . □

Lemma 11.

The action of (and hence ) on is transitive.

Proof.

Let and lie in

Since and , it follows that . □

The action of on is proper because is a discrete subgroup of with no accumulation points.

We now define an edge of and what it means for an unordered pair of edges to be equivalent. We show that the group acts freely and properly on the identification space of equivalent edges.

Let E be an open edge of . Since , it follows that is an open edge of . Let

Then is the set of open edges of by 12. Since is the center of , the element of is a rotation-reflection of , which sends an edge of to another edge of . Thus, sends into itself. For let be the set of unordered pairs of equivalent open edges of , that is, , so the open edges and of are not adjacent, which implies that the open edges E and of are not adjacent, and for some generator of the group of reflections with we have

Let . So is the set of unordered pairs of equivalent edges of . Define an action * of on by

where .

Define a relation ∼ on as follows. We say that x and are related, , if 1) and such that , where with for some and for some , or 2) x, and . Then ∼ is an equivalence relation on . Let be the set of equivalence classes and let be the map

which assigns to every the equivalence class containing p.

Lemma 12.

is the map ρ (20).

Proof.

This follows immediately from the definition of the maps and . □

Lemma 13.

The usual action of on , restricted to , is compatible with the equivalence relation ∼, that is, if x, and , then for every .

Proof.

Suppose that , where . Then , since . So for some with , we have . Let . Then

So . However, and . Hence . □

Because of Lemma 13, the usual -action on induces an action of on .

Lemma 14.

The action of on is free and proper.

Proof.

The following argument shows that it is free. Using Lemma A2 we see that an element of , which lies in the isotropy group for , interchanges the edge F with the equivalent edge and thus fixes the equivalence class for every . Hence the action on is free. It is proper because is a discrete subgroup of the Euclidean group with no accumulation points. □

Theorem 4.

The -orbit space is holomorphically diffeomorphic to the G-orbit space .

Proof.

The claim follows because the fundamental domain of the -action on is is the fundamental domain of the G-action on . Thus, is a fundamental domain of the -action on , which is equal to = by Lemma 12. Hence the -orbit space is equal to the G-orbit space . So the identity map from to induces a holomorphic diffeomorphism of orbit spaces. □

Because the group is a discrete subgroup of the 2-dimensional Euclidean group , the Riemann surface is an affine model of the affine Riemann surface .

6. The Developing Map and Geodesics

In this section, we show that the mapping

straightens the holomorphic vector field X (12) on the fundamental domain , see [6] and Flaschka [7]. We also verify that X is the geodesic vector field for a flat Riemannian metric on .

First we rewrite Equation (13) as

From the definition of the mapping (2) we get

where we use the same complex nth root as in the definition of . This implies

So the holomorphic vector field X (12) on and the holomorphic vector field on Q are -related. Hence sends an integral curve of the vector field X starting at onto an integral curve of the vector field starting at . Since an integral curve of is a horizontal line segment in Q, we have proved

Theorem 5.

We can say more. Let and . Then

is the flat Euclidean metric on . Its restriction to is invariant under the group , which is a subgroup of the Euclidean group .

Consider the flat Riemannian metric on Q, where is the metric (38) on . Pulling back by the mapping (2) gives a metric

on . Pulling the metric back by the projection mapping gives

on . Restricting to the affine Riemann surface gives .

Lemma 15.

Γ is a flat Riemannian metric on .

Proof.

We compute. For every we have

Thus, is a Riemannian metric on . It is flat by construction. □

Because has nonempty interior and the map (35) is holomorphic, it can be analytically continued to the map

since . By construction . So the mapping is an isometry of onto . In particular, the map is an isometry of onto . Moreover, is a local holomorphic diffeomorphism, because for every , the complex linear mapping is an isomorphism, since it sends to . Thus, is a developing map in the sense of differential geometry, see Spivak ([8], p. 97) note on §12 of Gauss [9]. The map is local because the integral curves of on Q are only defined for a finite time, since they are horizontal line segments in Q. Thus, the integral curves of X (12) on are defined for a finite time. Since the integral curves of are geodesics on , the image of a local integral curve of under the local inverse of the mapping is a local integral curve of X. This latter local integral curve is a geodesic on , since is an isometry. Thus, we have proved

Theorem 6.

The holomorphic vector field X (12) on the fundamental domain is the geodesic vector field for the flat Riemannian metric on .

Corollary 13.

The holomorphic vector field X on the affine Riemann surface is the geodesic vector field for the flat Riemannian metric Γ on .

Proof.

The corollary follows by analytic continuation from the conclusion of Theorem 6, since is a nonempty open subset of and both the vector field X and the Riemannian metric are holomorphic on . □

7. Discrete Symmetries and Billiard Motions

Let be the group of homeomorphisms of the affine Riemann surface (3) generated by the mappings

Clearly, the relations hold. For every we have

So the additional relation holds. Thus, is isomorphic to the dihedral group.

Lemma 16.

is a group of isometries of .

Proof.

For every we get

and

□

Recall that the group G, generated by the linear mappings

is isomorphic to the dihedral group.

Lemma 17.

G is a group of isometries of .

Proof.

This follows because R and U are Euclidean motions. □

We would like the developing map (39) to intertwine the actions of and G and the geodesic flows on and . There are several difficulties. The first is: the group G does not preserve the quadrilateral Q. To overcome this difficulty we extend the mapping (39) to the mapping (17) of the affine Riemann surface onto the regular stellated n-gon .

Lemma 18.

Proof.

From the definition of the mapping we see that for each we have for every . By analytic continuation we see that the preceding equation holds for every . Since by construction and (11), from the definition of the mapping (35) we get for every . In other words, for every . By analytic continuation we see that the preceding equation holds for all . Hence on we have

The mapping sends the generators and of the group to the generators R and U of the group G, respectively. So it is an isomorphism. □

There is a second more serious difficulty: the integral curves of run off the quadrilateral Q in finite time. We fix this by requiring that when an integral curve reaches a point P on the boundary of Q, which is not a vertex, it undergoes a specular reflection at P. (If the integral curve reaches a vertex of Q in forward or backward time, then the motion ends). This motion can be continued as a straight line motion, which extends the motion on the original segment in Q.

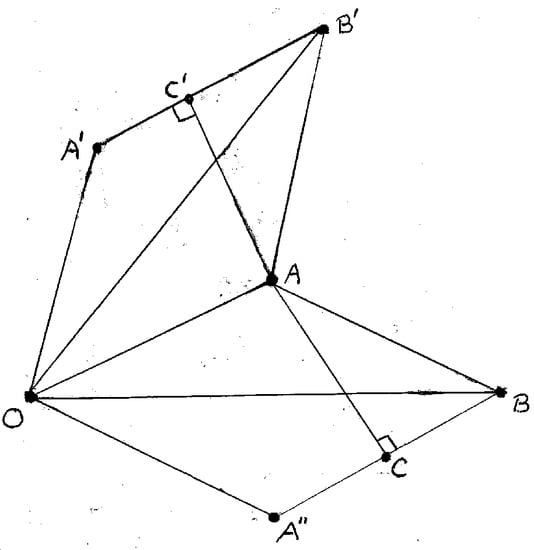

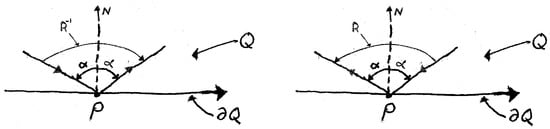

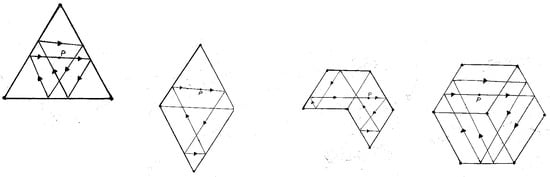

To make this precise, we give Q the orientation induced from and suppose that the incoming (and hence outgoing) straight line motion has the same orientation as . If the incoming motion makes an angle with respect to the inward pointing normal N to at P, then the outgoing motion makes an angle with the normal N, see Richens and Berry [2]. Specifically, if the incoming motion to P is an integral curve of , then the outgoing motion, after reflection at P, is an integral curve of . Thus, the outward motion makes a turn of at P towards the interior of Q, see Figure 10 (left). In Figure 10 (right) the incoming motion has the opposite orientation from . This extended motion on Q is called a billiard motion. A billiard motion starting in the interior of is defined for all time and remains in less its vertices, since each of the segments of the billiard motion is a straight line parallel to an edge of and does not hit a vertex of , see Figure 11.

Figure 10.

Reflection at a point P on .

Figure 11.

A periodic billiard motion in the equilateral triangle starting at P. First, extended by the reflection U to a periodic billiard motion in the quadrilateral . Second, extended by the relection S to a periodic billiard motion in . Third, extended by the reflection to a periodic billiard motion in the stellated equilateral triangle .

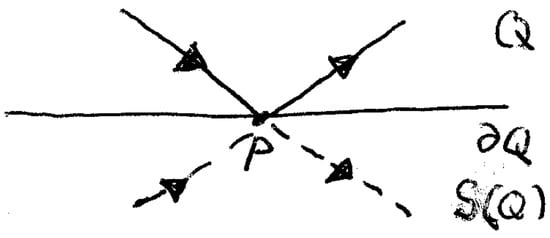

We can do more. If we apply a reflection S in the edge of Q in its boundary , which contains the reflection point P, to the initial reflected motion at P, see Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Continuation of a billiard motion in the quadrilateral Q to a billiard motion in the quarilateral obtained by the reflection S in an edge of Q.

The motion in when it reaches , et cetera, the extended motion becomes a billiard motion in the regular stellated n-gon , see Figure 11. So we have verified

Theorem 7.

A billiard motion in the regular stellated n-gon , which starts at a point in the interior of and does not hit a vertex of , is invariant under the action of the isometry subgroup of the isometry group G of generated by the rotation R.

Let be the subgroup of generated by the rotation . We now show

Lemma 19.

The holomorphic vector field X (12) on is -invariant.

Proof.

We compute. For every and for we have

Hence for every we get

for every . In other words, the vector field X is invariant under the action of on . □

Corollary 14.

For every we have

Corollary 15.

Every geodesic on is -invariant.

Proof.

This follows immediately from the lemma. □

Lemma 20.

For every and every we have

Proof.

From Equation (41) we get on . Differentiating the preceding equation and then evaluating the result at gives

for all . When , by definition . So for every

Thus,

for every . By analytic continuation (45) holds for every . Now sends to . Since for every , it follows that is in . Furthermore, since sends to , we get

We now show

Theorem 8.

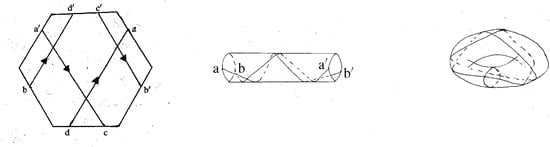

The image of a invariant geodesic on under the developing map (17) is a billiard motion in , see Figure 13.

Figure 13.

(left) A billiard motion in . (center) The points c, and d, in are identified, which results in motion on a cylinder. (right) After identifying the points a, and b, on the cylinder the motion becomes a periodic geodesic on on a smooth 2-torus less three points.

Proof.

Because and are isometries of and , respectively, it follows from equation (41) that the surjective map (17) is an isometry. Hence is a local developing map. Using the local inverse of and Equation (44), it follows that a billiard motion in is mapped onto a geodesic in , which is possibly broken at the points . Here are the points where the billiard motion undergoes a reflection. However, the geodesic on is smooth at since the geodesic vector field X is holomorphic on . Thus, the image of the geodesic under the developing map is a billiard motion. □

Theorem 9.

Under the restriction of the mapping

to the image of a billiard motion is a smooth geodesic on , where .

Proof.

Since the Riemannian metric on is invariant under the group of Euclidean motions, the Riemannian metric on is -invariant. Hence is invariant under the reflection for . So pieces together to give a Riemannian metric on the identification space . In other words, the pull back of under the map , which identifies equivalent edges of , is the metric . Since intertwines the G-action on with the G-action on , the metric is -invariant. It is flat because the metric is flat. So induces a flat Riemannian metric on the orbit space . Since the billiard motion is a -invariant broken geodesic on , it gives rise to a continuous broken geodesic on , which is -invariant. Thus, is a piecewise smooth geodesic on the smooth G-orbit space .

We need only show that is smooth. To see this we argue as follows. Let be a closed segment of a billiard motion , that does not meet a vertex of . Then s is a horizontal straight line motion in . Suppose that is the edge of , perpendicular to the direction , which is first met by s and let be the meeting point. Let be the reflection in . The continuation of the motion s at is the horizontal line in . Recall that is the translation of by . Using a suitable sequence of reflections in the edges of a suitable each followed by a rotation R and then a translation in corresponding to their origins, we extend s to a smooth straight line in , see Figure 14. The line is a geodesic in , which in has image under the -orbit map (47) that is a smooth geodesic on . The geodesic starts at . Thus, the smooth geodesic and the geodesic are equal. In other words, is a smooth geodesic. □

Figure 14.

The billiard motion in the stellated regular 3-gon meets the edge 0, isreflected in this edge by , and then is rotated by R. This gives an extended motion , which is a straight line that is the same as reflecting by U and then translating by .

Thus, the affine orbit space with flat Riemannian metric is the affine analogue of the Poincaré model of the affine Riemann surface as an orbit space of a discrete subgroup of acting on the unit disk in with the Poincaré metric.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Group Theoretic Properties

In this appendix we discuss some group theoretic properties of the set of equivalent edges of , which we use to determine the topology of .

Let be the set of unordered pairs of nonadjacent edges of . Define an action • of G on by

for every unordered pair of nonadjacent edges of . For every the edges and are nonadjacent. This follows because the edges E and are nonadjacent and the elements of G are invertible mappings of into itself. So . Thus, the mapping • is well defined. It is an action because for every g and we have

Since , the action • of G on induces an action · of the group of reflections on the set of equivalent edges of , which is defined by

for every , every edge E of , and every generator of , where . Since by Corollary 6, the mapping · is well defined.

Lemma A1.

The group G action • sends a -orbit on to another -orbit on .

Proof.

Consider the -orbit of . For every we have

because is a normal subgroup of G by Corollary 7. Since

and by Corollary 6, it follows that . □

Lemma A2.

For every and every the isotropy group of the action on at is .

Proof.

Every satisfies

if and only if

if and only if one of the statements 1) & or 2) & holds. From in 1) we get using Lemma 3. To see this we argue as follows. If , then for some and some , see Equation (A1). Suppose that with . Then , which contradicts our hypothesis. Now suppose that . Then , which gives . Let A and B be end points of the edge E. Then the reflection sends A to B and B to A, while the rotation sends A to A and B to B. Thus, , which is a contradiction. Hence . If in 2), then . So by Lemma 3, that is, . □

For every and every let be the isotropy group of the action on at . Since is an abelian subgroup of , it is a normal subgroup. Thus, is a subgroup of of order . This proves

Lemma A3.

For every and each the -orbit of in is equal to the -orbit of in .

Lemma A4.

For we have .

Proof.

Since

we get . Because the group is generated by the reflections for , it follows that

is a subgroup of G of order . Clearly the isotropy group is an abelian subgroup of . Hence , where is a subgroup of of order . Thus, the group has the same order as its subgroup . So . However, . □

Let . Then

So

This proves

since every may be written uniquely as for some and some .

References

- Aurell, E.; Itzykson, C. Rational billiards and algebraic curves. J. Geom. Phys. 1988, 5, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richens, P.J.; Berry, M.V. Pseudointegrable systems in classical and quantum mechanics. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 1981, 2, 495–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M. Geometry Revealed. A Jacob’s Ladder to Modern Higher Geometry; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Weyl, H. The Concept of a Riemann Surface; Dover: Mineola, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- McKean, H.; Moll, V. Elliptic Curves; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, L.; Cushman, R. Complete integrability beyond Liouville–Arnol’d. Rep. Math. Phys. 2005, 56, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaschka, H. A remark on integrable Hamiltonian systems. Phys. Lett. A 1988, 131, 505–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spivak, M. A Comprehensive Introduction to Differential Geometry; Publish or Perish: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1979; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Gauss, C.F. Disquisitiones generales circa superficies curvas. In English Translation: General Investigations of Curved Surfaces of 1825 and 1827; Hiltebeitel, A., Morehead, J., Eds.; Princeton University Library: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1902; Available online: www.gutenberg.org/files/36856/36856-pdf.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2020).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).