Abstract

The algebraic approach to bundles in non-commutative geometry and the definition of quantum real weighted projective spaces are reviewed. Principal U (1)-bundles over quantum real weighted projective spaces are constructed. As the spaces in question fall into two separate classes, the negative or odd class that generalises quantum real projective planes and the positive or even class that generalises the quantum disc, so do the constructed principal bundles. In the negative case the principal bundle is proven to be non-trivial and associated projective modules are described. In the positive case the principal bundles turn out to be trivial, and so all the associated modules are free. It is also shown that the circle (co)actions on the quantum Seifert manifold that define quantum real weighted projective spaces are almost free.

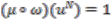

1. Introduction

In an algebraic setup an action of a circle on a quantum space corresponds to a coaction of a Hopf algebra of Laurent polynomials in one variable on the noncommutative coordinate algebra of the quantum space. Such a coaction can equivalently be understood as a  -grading of this coordinate algebra. A typical

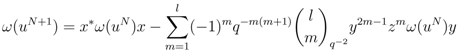

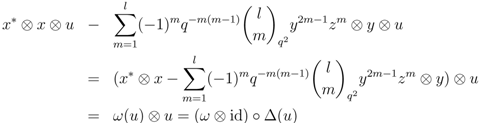

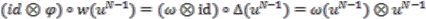

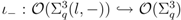

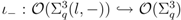

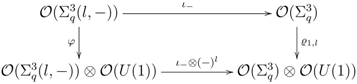

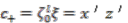

-grading of this coordinate algebra. A typical  -grading assigns degree ±1 to every generator of this algebra (different from the identity). The degree zero part forms a subalgebra which in particular cases corresponds to quantum complex or real projective spaces (grading of coordinate algebras of quantum spheres [1] or prolonged quantum spheres [2]). Often this grading is strong, meaning that the product of

-grading assigns degree ±1 to every generator of this algebra (different from the identity). The degree zero part forms a subalgebra which in particular cases corresponds to quantum complex or real projective spaces (grading of coordinate algebras of quantum spheres [1] or prolonged quantum spheres [2]). Often this grading is strong, meaning that the product of  -graded parts is equal to the

-graded parts is equal to the  -part of the total algebra. In geometric terms this reflects the freeness of the circle action.

-part of the total algebra. In geometric terms this reflects the freeness of the circle action.

-grading of this coordinate algebra. A typical

-grading of this coordinate algebra. A typical  -grading assigns degree ±1 to every generator of this algebra (different from the identity). The degree zero part forms a subalgebra which in particular cases corresponds to quantum complex or real projective spaces (grading of coordinate algebras of quantum spheres [1] or prolonged quantum spheres [2]). Often this grading is strong, meaning that the product of

-grading assigns degree ±1 to every generator of this algebra (different from the identity). The degree zero part forms a subalgebra which in particular cases corresponds to quantum complex or real projective spaces (grading of coordinate algebras of quantum spheres [1] or prolonged quantum spheres [2]). Often this grading is strong, meaning that the product of  -graded parts is equal to the

-graded parts is equal to the  -part of the total algebra. In geometric terms this reflects the freeness of the circle action.

-part of the total algebra. In geometric terms this reflects the freeness of the circle action.In two recent papers [3,4] circle actions on three-dimensional (and, briefly, higher dimensional) quantum spaces were revisited. Rather than assigning a uniform grade to each generator, separate generators were given degree by pairwise coprime integers. The zero part of such a grading of the coordinate algebra of the quantum odd-dimensional sphere corresponds to the quantum weighted projective space, while the zero part of such a grading of the algebra of the prolonged even dimensional quantum sphere leads to quantum real weighted projective spaces.

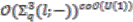

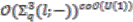

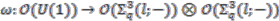

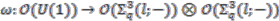

In this paper we focus on two classes of algebras  (

(  a positive integer) and

a positive integer) and  (

(  an odd positive integer) identified in [3] as fixed points of weighted circle actions on the coordinate algebra

an odd positive integer) identified in [3] as fixed points of weighted circle actions on the coordinate algebra  of a non-orientable quantum Seifert manifold described in [2]. Our aim is to construct quantum

of a non-orientable quantum Seifert manifold described in [2]. Our aim is to construct quantum  -principal bundles over the corresponding quantum spaces

-principal bundles over the corresponding quantum spaces  and describe associated line bundles. Recently, the importance of such bundles in non-commutative geometry was once again brought to the fore in [5], where the non-commutative Thom construction was outlined. As a further consequence of the principality of

and describe associated line bundles. Recently, the importance of such bundles in non-commutative geometry was once again brought to the fore in [5], where the non-commutative Thom construction was outlined. As a further consequence of the principality of  -coactions we also deduce that

-coactions we also deduce that  can be understood as quotients of

can be understood as quotients of  by almost free

by almost free  -actions.

-actions.

(

(  a positive integer) and

a positive integer) and  (

(  an odd positive integer) identified in [3] as fixed points of weighted circle actions on the coordinate algebra

an odd positive integer) identified in [3] as fixed points of weighted circle actions on the coordinate algebra  of a non-orientable quantum Seifert manifold described in [2]. Our aim is to construct quantum

of a non-orientable quantum Seifert manifold described in [2]. Our aim is to construct quantum  -principal bundles over the corresponding quantum spaces

-principal bundles over the corresponding quantum spaces  and describe associated line bundles. Recently, the importance of such bundles in non-commutative geometry was once again brought to the fore in [5], where the non-commutative Thom construction was outlined. As a further consequence of the principality of

and describe associated line bundles. Recently, the importance of such bundles in non-commutative geometry was once again brought to the fore in [5], where the non-commutative Thom construction was outlined. As a further consequence of the principality of  -coactions we also deduce that

-coactions we also deduce that  can be understood as quotients of

can be understood as quotients of  by almost free

by almost free  -actions.

-actions.We begin in Section 2 by reviewing elements of algebraic approach to classical and quantum bundles. We then proceed to describe algebras  in Section 3. Section 4 contains main results including construction of principal comodule algebras over

in Section 3. Section 4 contains main results including construction of principal comodule algebras over  . We observe that constructions albeit very similar in each case yield significantly different results. The principal comodule algebra over

. We observe that constructions albeit very similar in each case yield significantly different results. The principal comodule algebra over  is non-trivial while that over

is non-trivial while that over  turns out to be trivial (this means that all associated bundles are trivial, hence we do not mention them in the text). Whether it is a consequence of our particular construction or there is a deeper (topological or geometric) obstruction to constructing non-trivial principal circle bundles over

turns out to be trivial (this means that all associated bundles are trivial, hence we do not mention them in the text). Whether it is a consequence of our particular construction or there is a deeper (topological or geometric) obstruction to constructing non-trivial principal circle bundles over  remains an interesting open question.

remains an interesting open question.

in Section 3. Section 4 contains main results including construction of principal comodule algebras over

in Section 3. Section 4 contains main results including construction of principal comodule algebras over  . We observe that constructions albeit very similar in each case yield significantly different results. The principal comodule algebra over

. We observe that constructions albeit very similar in each case yield significantly different results. The principal comodule algebra over  is non-trivial while that over

is non-trivial while that over  turns out to be trivial (this means that all associated bundles are trivial, hence we do not mention them in the text). Whether it is a consequence of our particular construction or there is a deeper (topological or geometric) obstruction to constructing non-trivial principal circle bundles over

turns out to be trivial (this means that all associated bundles are trivial, hence we do not mention them in the text). Whether it is a consequence of our particular construction or there is a deeper (topological or geometric) obstruction to constructing non-trivial principal circle bundles over  remains an interesting open question.

remains an interesting open question.Throughout we work with involutive algebras over the field of complex numbers (but the algebraic results remain true for all fields of characteristic 0). All algebras are associative and have identity, we use the standard Hopf algebra notation and terminology and we always assume that the antipode of a Hopf algebra is bijective. All topological spaces are assumed to be Hausdorff.

2. Review of Bundles in Non-Commutative Geometry

The aim of this section is to set out the topological concepts in relation to topological bundles, in particular principal bundles. The classical connection is made for interpreting topological concepts in an algebraic setting, providing a manageable methodology for performing calculations. In particular, the connection between principal bundles in topology and the algebraic Hopf–Galois condition is described. The reader familiar with classical theory of bundles can proceed directly to Definition 2.14.

2.1. Topological Aspects of Bundles

As a natural starting point, bundles are defined and topological properties are described. The principal map is defined and shown that injectivity is equivalent to the freeness condition. The image of the canonical map is deduced and necessary conditions are imposed to ensure the bijectivity of this map. The detailed account of the material presented in this section can be found in [6].

Definition 2.1 A bundle is a triple  where

where  and

and  are topological spaces and

are topological spaces and  is a continuous surjective map. Here

is a continuous surjective map. Here  is called the base space,

is called the base space,  the total space and

the total space and  the projection of the bundle.

the projection of the bundle.

where

where  and

and  are topological spaces and

are topological spaces and  is a continuous surjective map. Here

is a continuous surjective map. Here  is called the base space,

is called the base space,  the total space and

the total space and  the projection of the bundle.

the projection of the bundle. For each  , the fibre over

, the fibre over  is the topological space

is the topological space  , i.e., the points on the total space which are projected, under

, i.e., the points on the total space which are projected, under  , onto the point

, onto the point  in the base space. A bundle whose fibres are homeomorphic which satisfies a condition known as local triviality are known as fibre bundles. This is formally expressed in the next definition.

in the base space. A bundle whose fibres are homeomorphic which satisfies a condition known as local triviality are known as fibre bundles. This is formally expressed in the next definition.

, the fibre over

, the fibre over  is the topological space

is the topological space  , i.e., the points on the total space which are projected, under

, i.e., the points on the total space which are projected, under  , onto the point

, onto the point  in the base space. A bundle whose fibres are homeomorphic which satisfies a condition known as local triviality are known as fibre bundles. This is formally expressed in the next definition.

in the base space. A bundle whose fibres are homeomorphic which satisfies a condition known as local triviality are known as fibre bundles. This is formally expressed in the next definition.Definition 2.2 A fibre bundle is a triple  where

where  is bundle and

is bundle and  is a topological space such that

is a topological space such that  are homeomorphic to

are homeomorphic to  for each

for each  . Furthermore,

. Furthermore,  satisfies the local triviality condition.

satisfies the local triviality condition.

where

where  is bundle and

is bundle and  is a topological space such that

is a topological space such that  are homeomorphic to

are homeomorphic to  for each

for each  . Furthermore,

. Furthermore,  satisfies the local triviality condition.

satisfies the local triviality condition. The local triviality condition is satisfied if for each  , there is an open neighourhood

, there is an open neighourhood  such that

such that  is homeomorphic to the product space

is homeomorphic to the product space  , in such a way that

, in such a way that  carries over to the projection onto the first factor. That is the following diagram commutes:

carries over to the projection onto the first factor. That is the following diagram commutes:

, there is an open neighourhood

, there is an open neighourhood  such that

such that  is homeomorphic to the product space

is homeomorphic to the product space  , in such a way that

, in such a way that  carries over to the projection onto the first factor. That is the following diagram commutes:

carries over to the projection onto the first factor. That is the following diagram commutes:

The map  is the natural projection

is the natural projection  and

and  is a homeomorphism.

is a homeomorphism.

is the natural projection

is the natural projection  and

and  is a homeomorphism.

is a homeomorphism.Example 2.3 An example of a fibre bundle which is non-trivial, i.e., not a global product space, is the Möbius strip. It has a circle that runs lengthwise through the centre of the strip as a base B and a line segment running vertically for the fibre F. The line segments are in fact copies of the real line, hence each  is homeomorphic to

is homeomorphic to  and the Mobius strip is a fibre bundle.

and the Mobius strip is a fibre bundle.

is homeomorphic to

is homeomorphic to  and the Mobius strip is a fibre bundle.

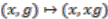

and the Mobius strip is a fibre bundle. Let  be a topological space which is compact and satisfies the Hausdorff property and G a compact topological group. Suppose there is a right action

be a topological space which is compact and satisfies the Hausdorff property and G a compact topological group. Suppose there is a right action  of

of  on

on  and write

and write  .

.

be a topological space which is compact and satisfies the Hausdorff property and G a compact topological group. Suppose there is a right action

be a topological space which is compact and satisfies the Hausdorff property and G a compact topological group. Suppose there is a right action  of

of  on

on  and write

and write  .

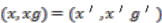

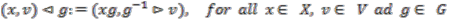

.Definition 2.4 An action of  on

on  is said to be free if

is said to be free if  for any

for any  implies that

implies that  , the group identity.

, the group identity.

on

on  is said to be free if

is said to be free if  for any

for any  implies that

implies that  , the group identity.

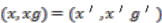

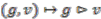

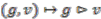

, the group identity. With an eye on algebraic formulation of freeness, the principal map  is defined as

is defined as  .

.

is defined as

is defined as  .

.Proposition 2.5  acts freely on

acts freely on  if and only if

if and only if  is injective.

is injective.

acts freely on

acts freely on  if and only if

if and only if  is injective.

is injective. Proof. “  " Suppose the action is free, hence

" Suppose the action is free, hence  implies that

implies that  . If

. If  , then

, then  and

and  . Applying the action of

. Applying the action of  to both sides of

to both sides of  we get

we get  , which implies

, which implies  by the freeness property, concluding

by the freeness property, concluding  and

and  is injective as required.

is injective as required.

" Suppose the action is free, hence

" Suppose the action is free, hence  implies that

implies that  . If

. If  , then

, then  and

and  . Applying the action of

. Applying the action of  to both sides of

to both sides of  we get

we get  , which implies

, which implies  by the freeness property, concluding

by the freeness property, concluding  and

and  is injective as required.

is injective as required.“  " Suppose

" Suppose  is injective, so

is injective, so  or

or  implies

implies  and

and  . Since

. Since  from the properties of the action, if

from the properties of the action, if  then

then  from the injectivity property.

from the injectivity property.

" Suppose

" Suppose  is injective, so

is injective, so  or

or  implies

implies  and

and  . Since

. Since  from the properties of the action, if

from the properties of the action, if  then

then  from the injectivity property.

from the injectivity property. Since  acts on

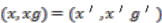

acts on  we can define the quotient space

we can define the quotient space  ,

,

acts on

acts on  we can define the quotient space

we can define the quotient space  ,

,

The sets  are called the orbits of the points

are called the orbits of the points  . They are defined as the set of elements in

. They are defined as the set of elements in  to which

to which  can be moved by the action of elements of

can be moved by the action of elements of  . The set of orbits of

. The set of orbits of  under the action of

under the action of  forms a partition of

forms a partition of  , hence we can define the equivalence relation on

, hence we can define the equivalence relation on  as,

as,

are called the orbits of the points

are called the orbits of the points  . They are defined as the set of elements in

. They are defined as the set of elements in  to which

to which  can be moved by the action of elements of

can be moved by the action of elements of  . The set of orbits of

. The set of orbits of  under the action of

under the action of  forms a partition of

forms a partition of  , hence we can define the equivalence relation on

, hence we can define the equivalence relation on  as,

as,

The equivalence relation is the same as saying  and

and  are in the same orbit, i.e.,

are in the same orbit, i.e.,  . Given any quotient space, then there is a canonical surjective map

. Given any quotient space, then there is a canonical surjective map

and

and  are in the same orbit, i.e.,

are in the same orbit, i.e.,  . Given any quotient space, then there is a canonical surjective map

. Given any quotient space, then there is a canonical surjective map

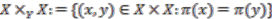

which maps elements in  to their orbits. We define the pull-back along this map

to their orbits. We define the pull-back along this map  to be the set

to be the set

to their orbits. We define the pull-back along this map

to their orbits. We define the pull-back along this map  to be the set

to be the set

As described above, the image of the principal map  contains elements of

contains elements of  in the first leg and the action of

in the first leg and the action of  on

on  in the second leg. To put it another way, the image records elements of

in the second leg. To put it another way, the image records elements of  in the first leg and all the elements in the same orbit as this

in the first leg and all the elements in the same orbit as this  in the second leg. Hence we can identify the image of the canonical map as the pull back along

in the second leg. Hence we can identify the image of the canonical map as the pull back along  , namely

, namely  . This is formally proved as a part of the following proposition.

. This is formally proved as a part of the following proposition.

contains elements of

contains elements of  in the first leg and the action of

in the first leg and the action of  on

on  in the second leg. To put it another way, the image records elements of

in the second leg. To put it another way, the image records elements of  in the first leg and all the elements in the same orbit as this

in the first leg and all the elements in the same orbit as this  in the second leg. Hence we can identify the image of the canonical map as the pull back along

in the second leg. Hence we can identify the image of the canonical map as the pull back along  , namely

, namely  . This is formally proved as a part of the following proposition.

. This is formally proved as a part of the following proposition.Proposition 2.6  acts freely on

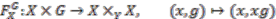

acts freely on  if and only if the map

if and only if the map

acts freely on

acts freely on  if and only if the map

if and only if the map

is bijective.

Proof. First note that the map  is well-defined since the elements

is well-defined since the elements  and

and  are in the same orbit and hence map to the same equivalence class under

are in the same orbit and hence map to the same equivalence class under  . Using Proposition 2.5 we can deduce that the injectivity of

. Using Proposition 2.5 we can deduce that the injectivity of  is equivalent to the freeness of the action. Hence if we can show that

is equivalent to the freeness of the action. Hence if we can show that  is surjective the proof is complete.

is surjective the proof is complete.

is well-defined since the elements

is well-defined since the elements  and

and  are in the same orbit and hence map to the same equivalence class under

are in the same orbit and hence map to the same equivalence class under  . Using Proposition 2.5 we can deduce that the injectivity of

. Using Proposition 2.5 we can deduce that the injectivity of  is equivalent to the freeness of the action. Hence if we can show that

is equivalent to the freeness of the action. Hence if we can show that  is surjective the proof is complete.

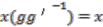

is surjective the proof is complete.Take  . This means

. This means  , which implies

, which implies  and

and  are in the same equivalence class, which in turn means they are in the same orbit. We can therefore deduce that

are in the same equivalence class, which in turn means they are in the same orbit. We can therefore deduce that  for some

for some  . So,

. So,  implying

implying  . Hence

. Hence  completing the proof.

completing the proof.

. This means

. This means  , which implies

, which implies  and

and  are in the same equivalence class, which in turn means they are in the same orbit. We can therefore deduce that

are in the same equivalence class, which in turn means they are in the same orbit. We can therefore deduce that  for some

for some  . So,

. So,  implying

implying  . Hence

. Hence  completing the proof.

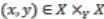

completing the proof. Definition 2.7 An action of  on

on  is said to be principal if the map

is said to be principal if the map  is both injective and continuous (and such that the inverse image of a compact subset is compact in a case of locally compact spaces).

is both injective and continuous (and such that the inverse image of a compact subset is compact in a case of locally compact spaces).

on

on  is said to be principal if the map

is said to be principal if the map  is both injective and continuous (and such that the inverse image of a compact subset is compact in a case of locally compact spaces).

is both injective and continuous (and such that the inverse image of a compact subset is compact in a case of locally compact spaces). Since the injectivity and freeness condition are equivalent, we can interpret principal actions as both free and continuous actions. We can also deduce that these types of actions give rise to homeomorphisms  from

from  onto the space

onto the space  . Principal actions lead to the concept of topological principle bundles.

. Principal actions lead to the concept of topological principle bundles.

from

from  onto the space

onto the space  . Principal actions lead to the concept of topological principle bundles.

. Principal actions lead to the concept of topological principle bundles.Definition 2.8 A principal bundle is a quadruple  such that

such that

such that

such that- (a)

is a bundle and

is a bundle and  is a topological group acting continuously on

is a topological group acting continuously on  with action

with action  ,

,  ;

; - (b) the action

is principal;

is principal; - (c)

such that

such that  ;

; - (d) the induced map

is a homeomorphism.

is a homeomorphism.

The first two properties tell us that principal bundles are bundles admitting a principal action of a group  on the total space

on the total space  , i.e., principal bundles correspond to principal actions. By Definition

, i.e., principal bundles correspond to principal actions. By Definition  , principal actions occur when the principal map is both injective and continuous, or equivalently, when the action is free and continuous. The third property ensures that the fibres of the bundle correspond to the orbits coming from the action and the final property implies that the quotient space can topologically be viewed as the base space of the bundle.

, principal actions occur when the principal map is both injective and continuous, or equivalently, when the action is free and continuous. The third property ensures that the fibres of the bundle correspond to the orbits coming from the action and the final property implies that the quotient space can topologically be viewed as the base space of the bundle.

on the total space

on the total space  , i.e., principal bundles correspond to principal actions. By Definition

, i.e., principal bundles correspond to principal actions. By Definition  , principal actions occur when the principal map is both injective and continuous, or equivalently, when the action is free and continuous. The third property ensures that the fibres of the bundle correspond to the orbits coming from the action and the final property implies that the quotient space can topologically be viewed as the base space of the bundle.

, principal actions occur when the principal map is both injective and continuous, or equivalently, when the action is free and continuous. The third property ensures that the fibres of the bundle correspond to the orbits coming from the action and the final property implies that the quotient space can topologically be viewed as the base space of the bundle.Example 2.9 Suppose  is a topological space and

is a topological space and  a topological group which acts on

a topological group which acts on  from the right. The triple

from the right. The triple  where

where  is the orbit space and

is the orbit space and  the natural projection is a bundle. A principal action of

the natural projection is a bundle. A principal action of  on

on  makes the quadruple

makes the quadruple  a principal bundle.

a principal bundle.

is a topological space and

is a topological space and  a topological group which acts on

a topological group which acts on  from the right. The triple

from the right. The triple  where

where  is the orbit space and

is the orbit space and  the natural projection is a bundle. A principal action of

the natural projection is a bundle. A principal action of  on

on  makes the quadruple

makes the quadruple  a principal bundle.

a principal bundle. We describe a principal bundle  as a

as a  -principal bundle over

-principal bundle over  , or

, or  as a

as a  -principal bundle over

-principal bundle over  .

.

as a

as a  -principal bundle over

-principal bundle over  , or

, or  as a

as a  -principal bundle over

-principal bundle over  .

.Definition 2.10 A vector bundle is a bundle  where each fibre

where each fibre  is endowed with a vector space structure such that addition and scalar multiplication are continuous maps.

is endowed with a vector space structure such that addition and scalar multiplication are continuous maps.

where each fibre

where each fibre  is endowed with a vector space structure such that addition and scalar multiplication are continuous maps.

is endowed with a vector space structure such that addition and scalar multiplication are continuous maps. Any vector bundle can be understood as a bundle associated to a principal bundle in the following way. Consider a  -principal bundle

-principal bundle  and let

and let  be a representation space of

be a representation space of  , i.e., a (topological) vector space with a (continuous) left

, i.e., a (topological) vector space with a (continuous) left  -action

-action  ,

,  . Then

. Then  acts from the right on

acts from the right on  by

by

-principal bundle

-principal bundle  and let

and let  be a representation space of

be a representation space of  , i.e., a (topological) vector space with a (continuous) left

, i.e., a (topological) vector space with a (continuous) left  -action

-action  ,

,  . Then

. Then  acts from the right on

acts from the right on  by

by

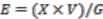

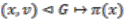

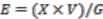

We can define  and a surjective (continuous map)

and a surjective (continuous map)  ,

,  and thus have a fibre bundle

and thus have a fibre bundle  . In the case where

. In the case where  is a vector space, we assume that

is a vector space, we assume that  acts linearly on

acts linearly on  .

.

and a surjective (continuous map)

and a surjective (continuous map)  ,

,  and thus have a fibre bundle

and thus have a fibre bundle  . In the case where

. In the case where  is a vector space, we assume that

is a vector space, we assume that  acts linearly on

acts linearly on  .

.Definition 2.11 A section of a bundle  is a continuous map

is a continuous map  such that, for all

such that, for all  ,

,

is a continuous map

is a continuous map  such that, for all

such that, for all  ,

,

i.e., a section is simply a section of the morphism  . The set of sections of

. The set of sections of  is denoted by

is denoted by  .

.

. The set of sections of

. The set of sections of  is denoted by

is denoted by  .

. Proposition 2.12 Sections in a fibre bundle  associated to a principal

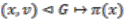

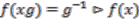

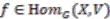

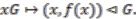

associated to a principal  -bundle

-bundle  are in bijective correspondence with (continuous) maps

are in bijective correspondence with (continuous) maps  such that

such that

associated to a principal

associated to a principal  -bundle

-bundle  are in bijective correspondence with (continuous) maps

are in bijective correspondence with (continuous) maps  such that

such that

All such  -equivariant maps are denoted by

-equivariant maps are denoted by  .

.

-equivariant maps are denoted by

-equivariant maps are denoted by  .

. Proof. Remember that  . Given a map

. Given a map  , define the section

, define the section  ,

,

. Given a map

. Given a map  , define the section

, define the section  ,

,

Conversely, given  , define

, define  by assigning to

by assigning to  a unique

a unique  such that

such that  . Note that

. Note that  is unique, since if

is unique, since if  , then

, then  and

and  . Freeness implies that

. Freeness implies that  , hence

, hence  . The map

. The map  has the required equivariance property, since the element of

has the required equivariance property, since the element of  corresponding to

corresponding to  is

is  .

.

, define

, define  by assigning to

by assigning to  a unique

a unique  such that

such that  . Note that

. Note that  is unique, since if

is unique, since if  , then

, then  and

and  . Freeness implies that

. Freeness implies that  , hence

, hence  . The map

. The map  has the required equivariance property, since the element of

has the required equivariance property, since the element of  corresponding to

corresponding to  is

is  .

. 2.2. Non-Commutative Principal and Associated Bundles

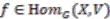

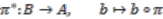

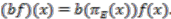

To make the transition from algebraic formulation of principal and associated bundles to non-commutative setup more transparent, we assume that  is a complex affine variety with an action of an affine algebraic group

is a complex affine variety with an action of an affine algebraic group  and set

and set  (all with the usual Euclidean topology). Let

(all with the usual Euclidean topology). Let  ,

,  and

and  be the corresponding coordinate rings. Put

be the corresponding coordinate rings. Put  and

and  and note the identification

and note the identification  . Through this identification,

. Through this identification,  is a Hopf algebra with comultiplication:

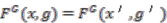

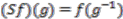

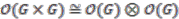

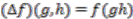

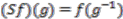

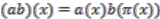

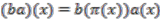

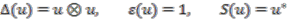

is a Hopf algebra with comultiplication:

, counit

, counit  ,

,  , and the antipode

, and the antipode  ,

,  .

.

is a complex affine variety with an action of an affine algebraic group

is a complex affine variety with an action of an affine algebraic group  and set

and set  (all with the usual Euclidean topology). Let

(all with the usual Euclidean topology). Let  ,

,  and

and  be the corresponding coordinate rings. Put

be the corresponding coordinate rings. Put  and

and  and note the identification

and note the identification  . Through this identification,

. Through this identification,  is a Hopf algebra with comultiplication:

is a Hopf algebra with comultiplication:

, counit

, counit  ,

,  , and the antipode

, and the antipode  ,

,  .

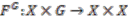

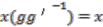

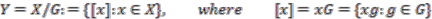

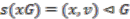

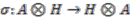

.Using the fact that  acts on

acts on  we can construct a right coaction of

we can construct a right coaction of  on

on  by

by  ,

,  . This coaction is an algebra map due to the commutativity of the algebras of functions involved.

. This coaction is an algebra map due to the commutativity of the algebras of functions involved.

acts on

acts on  we can construct a right coaction of

we can construct a right coaction of  on

on  by

by  ,

,  . This coaction is an algebra map due to the commutativity of the algebras of functions involved.

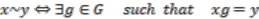

. This coaction is an algebra map due to the commutativity of the algebras of functions involved.We have viewed the spaces of polynomial functions on  and

and  , next we view the space of functions on Y,

, next we view the space of functions on Y,  , where

, where  .

.  is a subalgebra of

is a subalgebra of  by

by

and

and  , next we view the space of functions on Y,

, next we view the space of functions on Y,  , where

, where  .

.  is a subalgebra of

is a subalgebra of  by

by

where  is the canonical surjection defined above. The map

is the canonical surjection defined above. The map  is injective, since

is injective, since  in

in  means there exists at least one orbit

means there exists at least one orbit  such that

such that  , but

, but  , so

, so  which implies

which implies  . Therefore, we can identify

. Therefore, we can identify  with

with  . Furthermore,

. Furthermore,  if and only if

if and only if

is the canonical surjection defined above. The map

is the canonical surjection defined above. The map  is injective, since

is injective, since  in

in  means there exists at least one orbit

means there exists at least one orbit  such that

such that  , but

, but  , so

, so  which implies

which implies  . Therefore, we can identify

. Therefore, we can identify  with

with  . Furthermore,

. Furthermore,  if and only if

if and only if

for all  ,

,  . This is the same as

. This is the same as

,

,  . This is the same as

. This is the same as

for all  ,

,  , where

, where  is the unit function

is the unit function  (the identity element of

(the identity element of  ). Thus we can identify

). Thus we can identify  with the coinvariants of the coaction

with the coinvariants of the coaction  :

:

,

,  , where

, where  is the unit function

is the unit function  (the identity element of

(the identity element of  ). Thus we can identify

). Thus we can identify  with the coinvariants of the coaction

with the coinvariants of the coaction  :

:

Since  is a subalgebra of

is a subalgebra of  , it acts on

, it acts on  via the inclusion map

via the inclusion map  ,

,  . We can identify

. We can identify  with

with  by the map

by the map

is a subalgebra of

is a subalgebra of  , it acts on

, it acts on  via the inclusion map

via the inclusion map  ,

,  . We can identify

. We can identify  with

with  by the map

by the map

Note that  is well defined because

is well defined because  . Proposition 2.6 immediately yields

. Proposition 2.6 immediately yields

is well defined because

is well defined because  . Proposition 2.6 immediately yields

. Proposition 2.6 immediately yieldsProposition 2.13 The action of  on

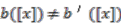

on  is free if and only if

is free if and only if  ,

,  is bijective.

is bijective.

on

on  is free if and only if

is free if and only if  ,

,  is bijective.

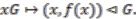

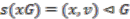

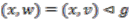

is bijective. In view of the definition of the coaction of  on

on  , we can identify

, we can identify  with the canonical map

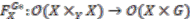

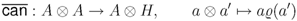

with the canonical map

on

on  , we can identify

, we can identify  with the canonical map

with the canonical map

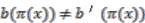

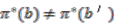

Thus the action of  on

on  is free if and only if this purely algebraic map is bijective. In the classical geometry case we take

is free if and only if this purely algebraic map is bijective. In the classical geometry case we take  ,

,  and

and  , but in general there is no need to restrict oneself to commutative algebras (of functions on topological spaces). In full generality this leads to the following definition.

, but in general there is no need to restrict oneself to commutative algebras (of functions on topological spaces). In full generality this leads to the following definition.

on

on  is free if and only if this purely algebraic map is bijective. In the classical geometry case we take

is free if and only if this purely algebraic map is bijective. In the classical geometry case we take  ,

,  and

and  , but in general there is no need to restrict oneself to commutative algebras (of functions on topological spaces). In full generality this leads to the following definition.

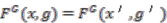

, but in general there is no need to restrict oneself to commutative algebras (of functions on topological spaces). In full generality this leads to the following definition.Definition 2.14 (Hopf–Galois Extensions) Let  be a Hopf algebra and

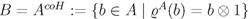

be a Hopf algebra and  a right

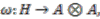

a right  -comodule algebra with coaction

-comodule algebra with coaction  . Let

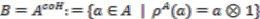

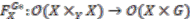

. Let  , the coinvariant subalgebra of

, the coinvariant subalgebra of  . We say that

. We say that  is a Hopf–Galois extension if the left

is a Hopf–Galois extension if the left  -module, right

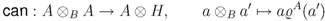

-module, right  -comodule map

-comodule map

be a Hopf algebra and

be a Hopf algebra and  a right

a right  -comodule algebra with coaction

-comodule algebra with coaction  . Let

. Let  , the coinvariant subalgebra of

, the coinvariant subalgebra of  . We say that

. We say that  is a Hopf–Galois extension if the left

is a Hopf–Galois extension if the left  -module, right

-module, right  -comodule map

-comodule map

is an isomorphism.

Proposition 2.13 tells us that when viewing bundles from an algebraic perspective, the freeness condition is equivalent to the Hopf–Galois extension property. Hence, the Hopf–Galois extension condition is a necessary condition to ensure a bundle is principal. Not all information about a topological space is encoded in a coordinate algebra, so to make a fuller reflection of the richness of the classical notion of a principal bundle we need to require conditions additional to the Hopf–Galois property.

Definition 2.15 Let  be a Hopf algebra with bijective antipode and let

be a Hopf algebra with bijective antipode and let  be a right

be a right  -comodule algebra with coaction

-comodule algebra with coaction  . Let

. Let  denote the coinvariant subalgebra of

denote the coinvariant subalgebra of  . We say that

. We say that  is a principal

is a principal  -comodule algebra if:

-comodule algebra if:

be a Hopf algebra with bijective antipode and let

be a Hopf algebra with bijective antipode and let  be a right

be a right  -comodule algebra with coaction

-comodule algebra with coaction  . Let

. Let  denote the coinvariant subalgebra of

denote the coinvariant subalgebra of  . We say that

. We say that  is a principal

is a principal  -comodule algebra if:

-comodule algebra if:- (a)

is a Hopf–Galois extension;

is a Hopf–Galois extension; - (b) the multiplication map

,

,  , splits as a left

, splits as a left  -module and right

-module and right  -comodule map (the equivariant projectivity condition).

-comodule map (the equivariant projectivity condition).

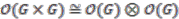

As indicated already in [7,8,9], principal comodule algebras should be understood as principal bundles in noncommutative geometry. In particular, if  is the Hopf algebra associated to a

is the Hopf algebra associated to a  -algebra of functions on a quantum group [10], then the existence of the Haar measure together with the results of [8] mean that condition (a) in Definition 2.15 implies condition (b) (i.e., the freeness of the coaction implies its principality).

-algebra of functions on a quantum group [10], then the existence of the Haar measure together with the results of [8] mean that condition (a) in Definition 2.15 implies condition (b) (i.e., the freeness of the coaction implies its principality).

is the Hopf algebra associated to a

is the Hopf algebra associated to a  -algebra of functions on a quantum group [10], then the existence of the Haar measure together with the results of [8] mean that condition (a) in Definition 2.15 implies condition (b) (i.e., the freeness of the coaction implies its principality).

-algebra of functions on a quantum group [10], then the existence of the Haar measure together with the results of [8] mean that condition (a) in Definition 2.15 implies condition (b) (i.e., the freeness of the coaction implies its principality).The following characterisation of principal comodule algebras [11,12] gives an effective method for proving the principality of coaction.

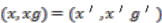

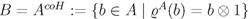

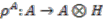

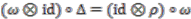

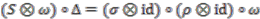

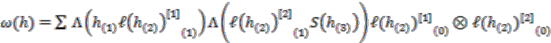

Proposition 2.16 A right  -comodule algebra

-comodule algebra  with coaction

with coaction  is principal if and only if it admits a strong connection form, that is if there exists a map

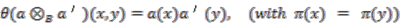

is principal if and only if it admits a strong connection form, that is if there exists a map  such that

such that

-comodule algebra

-comodule algebra  with coaction

with coaction  is principal if and only if it admits a strong connection form, that is if there exists a map

is principal if and only if it admits a strong connection form, that is if there exists a map  such that

such that

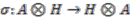

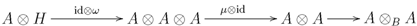

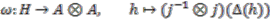

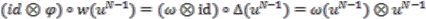

Here  denotes the multiplication map,

denotes the multiplication map,  is the unit map,

is the unit map,  is the comultiplication,

is the comultiplication,  counit and

counit and  the (bijective) antipode of the Hopf algebra

the (bijective) antipode of the Hopf algebra  , and

, and  is the flip.

is the flip.

denotes the multiplication map,

denotes the multiplication map,  is the unit map,

is the unit map,  is the comultiplication,

is the comultiplication,  counit and

counit and  the (bijective) antipode of the Hopf algebra

the (bijective) antipode of the Hopf algebra  , and

, and  is the flip.

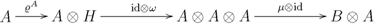

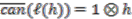

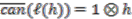

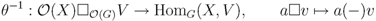

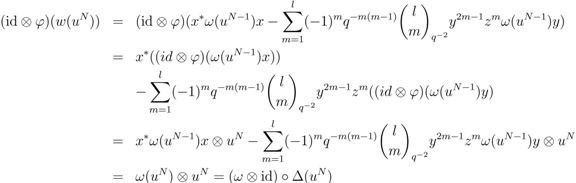

is the flip. Proof. If a strong connection form  exists, then the inverse of the canonical map

exists, then the inverse of the canonical map  (see Definition 2.14 ) is the composite

(see Definition 2.14 ) is the composite

exists, then the inverse of the canonical map

exists, then the inverse of the canonical map  (see Definition 2.14 ) is the composite

(see Definition 2.14 ) is the composite

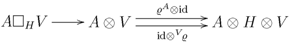

while the splitting of the multiplication map (see Definition 2.15 (b)) is given by

Conversely, if  is a principal comodule algebra, then

is a principal comodule algebra, then  is the composite

is the composite

is a principal comodule algebra, then

is a principal comodule algebra, then  is the composite

is the composite

where  is the left

is the left  -linear right

-linear right  -colinear splitting of the multiplication

-colinear splitting of the multiplication  .

.

is the left

is the left  -linear right

-linear right  -colinear splitting of the multiplication

-colinear splitting of the multiplication  .

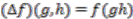

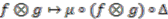

. Example 2.17 Let  be a right

be a right  -comodule algebra. The space of

-comodule algebra. The space of  -linear maps

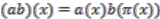

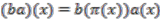

-linear maps  is an algebra with the convolution product

is an algebra with the convolution product

be a right

be a right  -comodule algebra. The space of

-comodule algebra. The space of  -linear maps

-linear maps  is an algebra with the convolution product

is an algebra with the convolution product

and unit  .

.  is said to be cleft if there exists a right

is said to be cleft if there exists a right  -colinear map

-colinear map  that has an inverse in the convolution algebra

that has an inverse in the convolution algebra  and is normalised so that

and is normalised so that  . Writing

. Writing  for the convolution inverse of

for the convolution inverse of  , one easily observes that

, one easily observes that

.

.  is said to be cleft if there exists a right

is said to be cleft if there exists a right  -colinear map

-colinear map  that has an inverse in the convolution algebra

that has an inverse in the convolution algebra  and is normalised so that

and is normalised so that  . Writing

. Writing  for the convolution inverse of

for the convolution inverse of  , one easily observes that

, one easily observes that

is a strong connection form. Hence a cleft comodule algebra is an example of a principal comodule algebra. The map  is called a cleaving map or a normalised total integral.

is called a cleaving map or a normalised total integral.

is called a cleaving map or a normalised total integral.

is called a cleaving map or a normalised total integral.In particular, if  is an

is an  -colinear algebra map, then it is automatically convolution invertible (as

-colinear algebra map, then it is automatically convolution invertible (as  ) and normalised. A comodule algebra

) and normalised. A comodule algebra  admitting such a map is termed a trivial principal comodule algebra.

admitting such a map is termed a trivial principal comodule algebra.

is an

is an  -colinear algebra map, then it is automatically convolution invertible (as

-colinear algebra map, then it is automatically convolution invertible (as  ) and normalised. A comodule algebra

) and normalised. A comodule algebra  admitting such a map is termed a trivial principal comodule algebra.

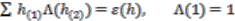

admitting such a map is termed a trivial principal comodule algebra. Example 2.18 Let  be a Hopf algebra of the compact quantum group. By the Woronowicz theorem [10],

be a Hopf algebra of the compact quantum group. By the Woronowicz theorem [10],  admits an invariant Haar measure, i.e., a linear map

admits an invariant Haar measure, i.e., a linear map  such that, for all

such that, for all  ,

,

be a Hopf algebra of the compact quantum group. By the Woronowicz theorem [10],

be a Hopf algebra of the compact quantum group. By the Woronowicz theorem [10],  admits an invariant Haar measure, i.e., a linear map

admits an invariant Haar measure, i.e., a linear map  such that, for all

such that, for all  ,

,

where  is the Sweedler notation for the comultiplication. Next, assume that the lifted canonical map:

is the Sweedler notation for the comultiplication. Next, assume that the lifted canonical map:

is the Sweedler notation for the comultiplication. Next, assume that the lifted canonical map:

is the Sweedler notation for the comultiplication. Next, assume that the lifted canonical map:

is surjective, and write

for the  -linear map such that

-linear map such that  , for all

, for all  . Then, by the Schneider theorem [8],

. Then, by the Schneider theorem [8],  is a principal

is a principal  -comodule algebra. Explicitly, a strong connection form is

-comodule algebra. Explicitly, a strong connection form is

-linear map such that

-linear map such that  , for all

, for all  . Then, by the Schneider theorem [8],

. Then, by the Schneider theorem [8],  is a principal

is a principal  -comodule algebra. Explicitly, a strong connection form is

-comodule algebra. Explicitly, a strong connection form is

where the coaction is denoted by the Sweedler notation  ; see [13].

; see [13].

; see [13].

; see [13]. Having described non-commutative principal bundles, we can look at the associated vector bundles. First we look at the classical case and try to understand it purely algebraically. Start with a vector bundle  associated to a principal

associated to a principal  -bundle

-bundle  . Since

. Since  is a vector representation space of

is a vector representation space of  , also the set

, also the set  is a vector space. Consequently

is a vector space. Consequently  is a vector space. Furthermore,

is a vector space. Furthermore,  is a left module of

is a left module of  with the action

with the action  To understand better the way in which

To understand better the way in which  -module

-module  is associated to the principal comodule algebra

is associated to the principal comodule algebra  we recall the notion of the cotensor product.

we recall the notion of the cotensor product.

associated to a principal

associated to a principal  -bundle

-bundle  . Since

. Since  is a vector representation space of

is a vector representation space of  , also the set

, also the set  is a vector space. Consequently

is a vector space. Consequently  is a vector space. Furthermore,

is a vector space. Furthermore,  is a left module of

is a left module of  with the action

with the action  To understand better the way in which

To understand better the way in which  -module

-module  is associated to the principal comodule algebra

is associated to the principal comodule algebra  we recall the notion of the cotensor product.

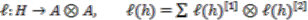

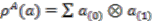

we recall the notion of the cotensor product. Definition 2.19 Given a Hopf algebra  , right

, right  -comodule

-comodule  with coaction

with coaction  and left

and left  -comodule

-comodule  with coaction

with coaction  , the cotensor product is defined as an equaliser:

, the cotensor product is defined as an equaliser:

, right

, right  -comodule

-comodule  with coaction

with coaction  and left

and left  -comodule

-comodule  with coaction

with coaction  , the cotensor product is defined as an equaliser:

, the cotensor product is defined as an equaliser:

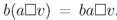

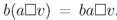

If  is an

is an  -comodule algebra, and

-comodule algebra, and  , the

, the  is a left

is a left  -module with the action

-module with the action  In particular, in the case of a principal

In particular, in the case of a principal  -bundle

-bundle  over

over  , for any left

, for any left  -comodule

-comodule  the cotensor product

the cotensor product  is a left

is a left  -module.

-module.

is an

is an  -comodule algebra, and

-comodule algebra, and  , the

, the  is a left

is a left  -module with the action

-module with the action  In particular, in the case of a principal

In particular, in the case of a principal  -bundle

-bundle  over

over  , for any left

, for any left  -comodule

-comodule  the cotensor product

the cotensor product  is a left

is a left  -module.

-module.The following proposition indicates the way in which cotensor products enter description of associated bundles.

Proposition 2.20 Assume that the fibre  of a vector bundle

of a vector bundle  associated to a principal

associated to a principal  -bundle

-bundle  is finite dimensional. View

is finite dimensional. View  as a left comodule of

as a left comodule of  with the coaction

with the coaction  (summation implicit) determined by

(summation implicit) determined by  Then the left

Then the left  -module of sections

-module of sections  is isomorphic to the left

is isomorphic to the left  -module

-module  .

.

of a vector bundle

of a vector bundle  associated to a principal

associated to a principal  -bundle

-bundle  is finite dimensional. View

is finite dimensional. View  as a left comodule of

as a left comodule of  with the coaction

with the coaction  (summation implicit) determined by

(summation implicit) determined by  Then the left

Then the left  -module of sections

-module of sections  is isomorphic to the left

is isomorphic to the left  -module

-module  .

. Proof. First identify  with

with  . Let

. Let  be a (finite) dual basis. Take

be a (finite) dual basis. Take  , and define

, and define  .

.

with

with  . Let

. Let  be a (finite) dual basis. Take

be a (finite) dual basis. Take  , and define

, and define  .

. In the converse direction, define a left  -module map

-module map

-module map

-module map

One easily checks that the constructed map are mutual inverses.

Moving away from commutative algebras of functions on topological spaces one uses Proposition 2.20 as the motivation for the following definition.

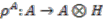

Definition 2.21 Let  be a principal

be a principal  -comodule algebra. Set

-comodule algebra. Set  and let

and let  be a left

be a left  -comodule. The left

-comodule. The left  -module

-module  is called a module associated to the principal comodule algebra

is called a module associated to the principal comodule algebra  .

.

be a principal

be a principal  -comodule algebra. Set

-comodule algebra. Set  and let

and let  be a left

be a left  -comodule. The left

-comodule. The left  -module

-module  is called a module associated to the principal comodule algebra

is called a module associated to the principal comodule algebra  .

.  is a projective left

is a projective left  -module, and if

-module, and if  is a finite dimensional vector space, then

is a finite dimensional vector space, then  is a finitely generated projective left

is a finitely generated projective left  -module. In this case it has the meaning of a module of sections over a non-commutative vector bundle. Furthermore, its class gives an element in the

-module. In this case it has the meaning of a module of sections over a non-commutative vector bundle. Furthermore, its class gives an element in the  -group of

-group of  . If

. If  is a cleft principal comodule algebra, then every associated module is free, since

is a cleft principal comodule algebra, then every associated module is free, since  as a left

as a left  -module and right

-module and right  -comodule, so that

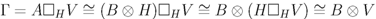

-comodule, so that

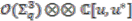

3. Weighted Circle Actions on Prolonged Spheres.

In this section we recall the definitions of algebras we study in the sequel.

3.1. Circle Actions and  -Gradings.

-Gradings.

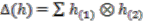

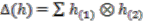

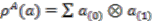

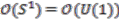

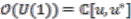

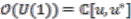

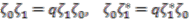

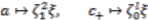

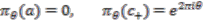

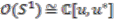

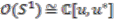

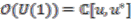

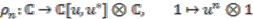

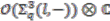

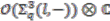

The coordinate algebra of the circle or the group  ,

,  can be identified with the

can be identified with the  -algebra

-algebra  of Laurent polynomials in a unitary variable

of Laurent polynomials in a unitary variable  (unitary means

(unitary means  ). As a Hopf

). As a Hopf  -algebra

-algebra  , is generated by the grouplike element

, is generated by the grouplike element  , i.e.,

, i.e.,

,

,  can be identified with the

can be identified with the  -algebra

-algebra  of Laurent polynomials in a unitary variable

of Laurent polynomials in a unitary variable  (unitary means

(unitary means  ). As a Hopf

). As a Hopf  -algebra

-algebra  , is generated by the grouplike element

, is generated by the grouplike element  , i.e.,

, i.e.,

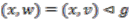

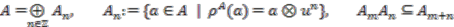

and thus it can be understood as the group algebra  . As a consequence of this interpretation of

. As a consequence of this interpretation of  , an algebra

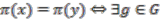

, an algebra  is a

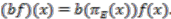

is a  -comodule algebra if and only if

-comodule algebra if and only if  is a

is a  -graded algebra,

-graded algebra,

. As a consequence of this interpretation of

. As a consequence of this interpretation of  , an algebra

, an algebra  is a

is a  -comodule algebra if and only if

-comodule algebra if and only if  is a

is a  -graded algebra,

-graded algebra,

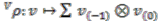

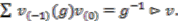

is the coinvariant subalgebra of

is the coinvariant subalgebra of  . Since

. Since  is spanned by grouplike elements, any convolution invertible map

is spanned by grouplike elements, any convolution invertible map  must assign a unit (invertible element) of

must assign a unit (invertible element) of  to

to  . Furthermore, colinear maps are simply the

. Furthermore, colinear maps are simply the  -degree preserving maps, where

-degree preserving maps, where  . Put together, convolution invertible colinear maps

. Put together, convolution invertible colinear maps  are in one-to-one correspondence with sequences

are in one-to-one correspondence with sequences

3.2. The  and

and  Coordinate Algebras

Coordinate Algebras

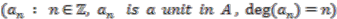

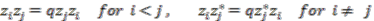

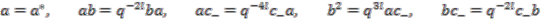

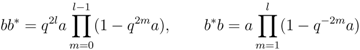

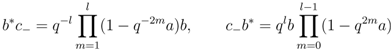

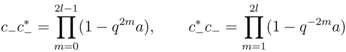

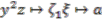

Let  be a real number,

be a real number,  . The coordinate algebra

. The coordinate algebra  of the even-dimensional quantum sphere is the unital complex

of the even-dimensional quantum sphere is the unital complex  -algebra with generators

-algebra with generators  , subject to the following relations:

, subject to the following relations:

be a real number,

be a real number,  . The coordinate algebra

. The coordinate algebra  of the even-dimensional quantum sphere is the unital complex

of the even-dimensional quantum sphere is the unital complex  -algebra with generators

-algebra with generators  , subject to the following relations:

, subject to the following relations:

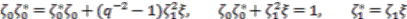

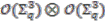

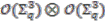

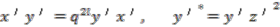

is a

is a  -graded algebra with

-graded algebra with  and so is

and so is  (with

(with  ). In other words,

). In other words,  is a right

is a right  -comodule algebra and

-comodule algebra and  is a left

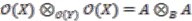

is a left  -comodule algebra, hence one can consider the cotensor product algebra

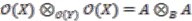

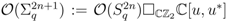

-comodule algebra, hence one can consider the cotensor product algebra  . It was shown in [2] that, as a unital

. It was shown in [2] that, as a unital  -algebra,

-algebra,  has generators

has generators  and a central unitary

and a central unitary  which are related in the following way:

which are related in the following way:

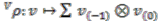

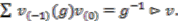

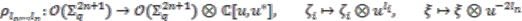

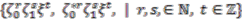

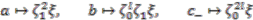

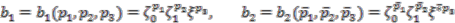

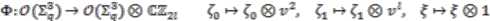

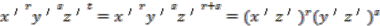

For any choice of  pairwise coprime numbers

pairwise coprime numbers  one can define the coaction of the Hopf algebra

one can define the coaction of the Hopf algebra  on

on  as

as

pairwise coprime numbers

pairwise coprime numbers  one can define the coaction of the Hopf algebra

one can define the coaction of the Hopf algebra  on

on  as

as

for  . This coaction is then extended to the whole of

. This coaction is then extended to the whole of  so that

so that  is a right

is a right  -comodule algebra.

-comodule algebra.

. This coaction is then extended to the whole of

. This coaction is then extended to the whole of  so that

so that  is a right

is a right  -comodule algebra.

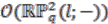

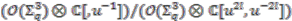

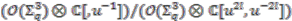

-comodule algebra.The algebra of coordinate functions on the quantum real weighted projective space is now defined as the subalgebra of  containing all coinvariant elements, i.e.,

containing all coinvariant elements, i.e.,

containing all coinvariant elements, i.e.,

containing all coinvariant elements, i.e.,

3.3. The 2D Quantum Real Projective Space

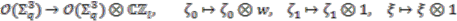

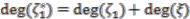

In this paper we consider two-dimensional quantum real weighted projective spaces, i.e., the algebras obtained from the coordinate algebra  which is generated by

which is generated by  and central unitary

and central unitary  such that

such that

which is generated by

which is generated by  and central unitary

and central unitary  such that

such that

The linear basis of  is

is

is

is

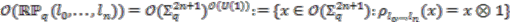

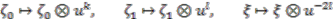

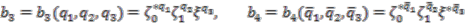

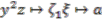

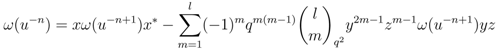

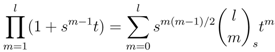

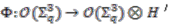

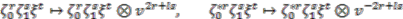

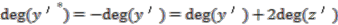

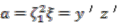

For a pair  of coprime positive integers, the coaction

of coprime positive integers, the coaction  is given on generators by

is given on generators by

of coprime positive integers, the coaction

of coprime positive integers, the coaction  is given on generators by

is given on generators by

and extended to the whole of  so that the coaction is a

so that the coaction is a  -algebra map. We denote the comodule algebra

-algebra map. We denote the comodule algebra  with coaction

with coaction  by

by  .

.

so that the coaction is a

so that the coaction is a  -algebra map. We denote the comodule algebra

-algebra map. We denote the comodule algebra  with coaction

with coaction  by

by  .

.It turns out that the two dimensional quantum real projective spaces split into two cases depending on not wholly the parameter  but instead whether

but instead whether  is either even or odd, and hence only cases

is either even or odd, and hence only cases  and

and  need to be considered [3]. We describe these cases presently.

need to be considered [3]. We describe these cases presently.

but instead whether

but instead whether  is either even or odd, and hence only cases

is either even or odd, and hence only cases  and

and  need to be considered [3]. We describe these cases presently.

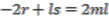

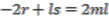

need to be considered [3]. We describe these cases presently.3.3.1. The Odd or Negative Case

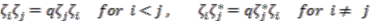

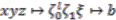

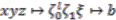

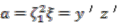

For  ,

,  is a polynomial

is a polynomial  -algebra generated by

-algebra generated by  ,

,  ,

,  which satisfy the relations:

which satisfy the relations:

,

,  is a polynomial

is a polynomial  -algebra generated by

-algebra generated by  ,

,  ,

,  which satisfy the relations:

which satisfy the relations:

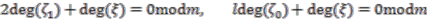

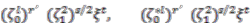

The embedding of generators of  into

into  or the isomorphism of

or the isomorphism of  with the coinvariants of

with the coinvariants of  is provided by

is provided by

into

into  or the isomorphism of

or the isomorphism of  with the coinvariants of

with the coinvariants of  is provided by

is provided by

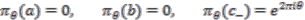

Up to equivalence  has the following irreducible

has the following irreducible  -representations. There is a family of one-dimensional representations labelled by

-representations. There is a family of one-dimensional representations labelled by  and given by

and given by

has the following irreducible

has the following irreducible  -representations. There is a family of one-dimensional representations labelled by

-representations. There is a family of one-dimensional representations labelled by  and given by

and given by

All other representations are infinite dimensional, labelled by  , and given by

, and given by

, and given by

, and given by

where  ,

,  , is an orthonormal basis for the representation space

, is an orthonormal basis for the representation space  .

.

,

,  , is an orthonormal basis for the representation space

, is an orthonormal basis for the representation space  .

.The  -algebra of continuous functions on

-algebra of continuous functions on  , obtained as the completion of these bounded representations, can be identified with the pullback of

, obtained as the completion of these bounded representations, can be identified with the pullback of  -copies of the quantum real projective plane

-copies of the quantum real projective plane  introduced in [14].

introduced in [14].

-algebra of continuous functions on

-algebra of continuous functions on  , obtained as the completion of these bounded representations, can be identified with the pullback of

, obtained as the completion of these bounded representations, can be identified with the pullback of  -copies of the quantum real projective plane

-copies of the quantum real projective plane  introduced in [14].

introduced in [14].3.3.2. The Even or Positive Case

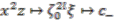

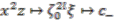

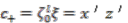

For  and hence

and hence  odd,

odd,  is a polynomial

is a polynomial  -algebra generated by

-algebra generated by  ,

,  which satisfy the relations:

which satisfy the relations:

and hence

and hence  odd,

odd,  is a polynomial

is a polynomial  -algebra generated by

-algebra generated by  ,

,  which satisfy the relations:

which satisfy the relations:

The embedding of generators of  into

into  or the isomorphism of

or the isomorphism of  with the coinvariants of

with the coinvariants of  is provided by

is provided by

into

into  or the isomorphism of

or the isomorphism of  with the coinvariants of

with the coinvariants of  is provided by

is provided by

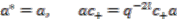

Similarly to the odd  case, there is a family of one-dimensional representations of

case, there is a family of one-dimensional representations of  labelled by

labelled by  and given by

and given by

case, there is a family of one-dimensional representations of

case, there is a family of one-dimensional representations of  labelled by

labelled by  and given by

and given by

All other representations are infinite dimensional, labelled by  , and given by

, and given by

, and given by

, and given by

where  ,

,  is an orthonormal basis for the representation space

is an orthonormal basis for the representation space  .

.

,

,  is an orthonormal basis for the representation space

is an orthonormal basis for the representation space  .

.The  -algebra

-algebra  of continuous functions on

of continuous functions on  , obtained as the completion of these bounded representations, can be identified with the pullback of

, obtained as the completion of these bounded representations, can be identified with the pullback of  -copies of the quantum disk

-copies of the quantum disk  introduced in [15]. Furthermore,

introduced in [15]. Furthermore,  can also be understood as the quantum double suspension of

can also be understood as the quantum double suspension of  points in the sense of [16, Definition 6.1].

points in the sense of [16, Definition 6.1].

-algebra

-algebra  of continuous functions on

of continuous functions on  , obtained as the completion of these bounded representations, can be identified with the pullback of

, obtained as the completion of these bounded representations, can be identified with the pullback of  -copies of the quantum disk

-copies of the quantum disk  introduced in [15]. Furthermore,

introduced in [15]. Furthermore,  can also be understood as the quantum double suspension of

can also be understood as the quantum double suspension of  points in the sense of [16, Definition 6.1].

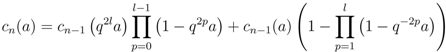

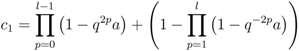

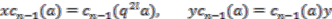

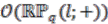

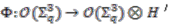

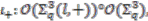

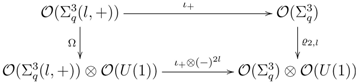

points in the sense of [16, Definition 6.1].4. Quantum Real Weighted Projective Spaces and Quantum Principal Bundles

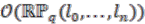

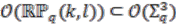

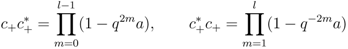

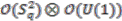

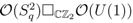

The general aim of this paper is to construct quantum principal bundles with base spaces given by  and fibre structures given by the circle Hopf algebra

and fibre structures given by the circle Hopf algebra  . The question arises as to which quantum space (i.e., a

. The question arises as to which quantum space (i.e., a  -comodule algebra with coinvariants isomorphic to

-comodule algebra with coinvariants isomorphic to  ) we should consider as the total space within this construction. We look first at the coactions of

) we should consider as the total space within this construction. We look first at the coactions of  on

on  that define

that define  , i.e., at the comodule algebras

, i.e., at the comodule algebras  .

.

and fibre structures given by the circle Hopf algebra

and fibre structures given by the circle Hopf algebra  . The question arises as to which quantum space (i.e., a

. The question arises as to which quantum space (i.e., a  -comodule algebra with coinvariants isomorphic to

-comodule algebra with coinvariants isomorphic to  ) we should consider as the total space within this construction. We look first at the coactions of

) we should consider as the total space within this construction. We look first at the coactions of  on

on  that define

that define  , i.e., at the comodule algebras

, i.e., at the comodule algebras  .

. 4.1. The (Non-)Principality of

Theorem 4.1  is a principal comodule algebra if and only if

is a principal comodule algebra if and only if  .

.

is a principal comodule algebra if and only if

is a principal comodule algebra if and only if  .

.Proof. As explained in [2]  is a prolongation of the

is a prolongation of the  -comodule algebra

-comodule algebra  . The latter is a principal comodule algebra (over the quantum real projective plane

. The latter is a principal comodule algebra (over the quantum real projective plane  [14]) and since a prolongation of a principal comodule algebra is a principal comodule algebra [8, Remark 3.11], the coaction

[14]) and since a prolongation of a principal comodule algebra is a principal comodule algebra [8, Remark 3.11], the coaction  is principal as stated.

is principal as stated.

is a prolongation of the

is a prolongation of the  -comodule algebra

-comodule algebra  . The latter is a principal comodule algebra (over the quantum real projective plane

. The latter is a principal comodule algebra (over the quantum real projective plane  [14]) and since a prolongation of a principal comodule algebra is a principal comodule algebra [8, Remark 3.11], the coaction

[14]) and since a prolongation of a principal comodule algebra is a principal comodule algebra [8, Remark 3.11], the coaction  is principal as stated.

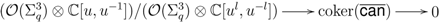

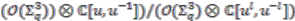

is principal as stated.In the converse direction, we aim to show that the canonical map is not an isomorphism by showing that the image does not contain  , i.e., it cannot be surjective since we know

, i.e., it cannot be surjective since we know  is in the codomain. We begin by identifying a basis for the algebra

is in the codomain. We begin by identifying a basis for the algebra  ; observing the relations in Equations (6a) and (6b) it is clear that a basis for

; observing the relations in Equations (6a) and (6b) it is clear that a basis for  is given by elements of the form

is given by elements of the form

, i.e., it cannot be surjective since we know

, i.e., it cannot be surjective since we know  is in the codomain. We begin by identifying a basis for the algebra

is in the codomain. We begin by identifying a basis for the algebra  ; observing the relations in Equations (6a) and (6b) it is clear that a basis for

; observing the relations in Equations (6a) and (6b) it is clear that a basis for  is given by elements of the form

is given by elements of the form

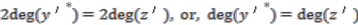

noting that all powers are non-negative. Hence a basis for  is given by elements of the form

is given by elements of the form  , where

, where  . Applying the canonial map gives

. Applying the canonial map gives

is given by elements of the form

is given by elements of the form  , where

, where  . Applying the canonial map gives

. Applying the canonial map gives

where  means

means  for simplicity of notation. The next stage is to construct all possible elements in

for simplicity of notation. The next stage is to construct all possible elements in  which map to

which map to  . To obtain the identity in the first leg we must use one of the following relations:

. To obtain the identity in the first leg we must use one of the following relations:

means

means  for simplicity of notation. The next stage is to construct all possible elements in

for simplicity of notation. The next stage is to construct all possible elements in  which map to

which map to  . To obtain the identity in the first leg we must use one of the following relations:

. To obtain the identity in the first leg we must use one of the following relations:

or

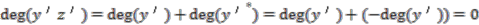

We see that to obtain identity in the first leg we require the powers of  and

and  to be equal. We now construct all possible elements of the domain which map to

to be equal. We now construct all possible elements of the domain which map to  after applying the canonical map.

after applying the canonical map.

and

and  to be equal. We now construct all possible elements of the domain which map to

to be equal. We now construct all possible elements of the domain which map to  after applying the canonical map.

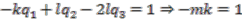

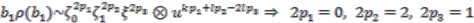

after applying the canonical map.Case 1: use the first relation to obtain  (

(  ); this can be done in fours ways. First, using

); this can be done in fours ways. First, using  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  . Now,

. Now,

(

(  ); this can be done in fours ways. First, using

); this can be done in fours ways. First, using  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  . Now,

. Now,

and

hence no possible terms. A similar calculation for the three other cases shows that  cannot be obtained as an element of the image of the canonical map in this case.

cannot be obtained as an element of the image of the canonical map in this case.

cannot be obtained as an element of the image of the canonical map in this case.

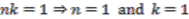

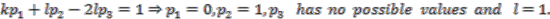

cannot be obtained as an element of the image of the canonical map in this case.Case 2: use the second relation to obtain  (

(  ); this can be done in four ways

); this can be done in four ways  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  . Now,

. Now,

(

(  ); this can be done in four ways

); this can be done in four ways  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  . Now,

. Now,

and

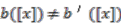

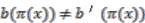

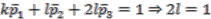

Note that  is not a problem provided

is not a problem provided  is not equal to

is not equal to  . This is reviewed at the next stage of the proof. The same conclusion is reached in all four cases.