Ore Characterization and Its Application to Beneficiation: The Case of Molai Zn-Pb±(Ag,Ge) Epithermal Ore, Laconia, SE Peloponnese, Greece

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Molai Deposit Geology

3. Methodology and Analytical Techniques

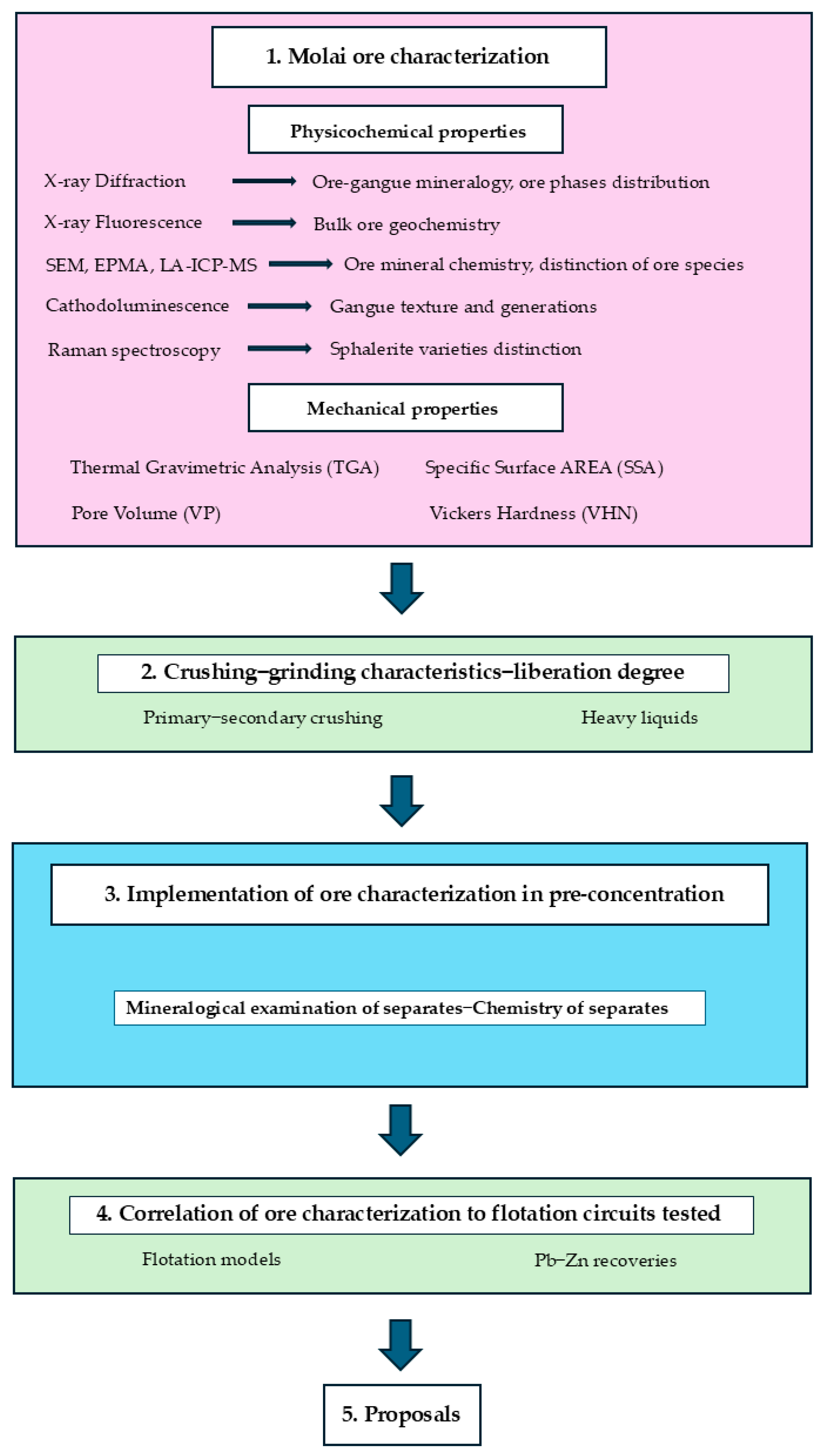

- Examination of the physicochemical and mechanical characteristics of the low-grade and fine-grained Molai sulfide ore (details in ESM-S1, ESM-S2);

- Examination of the crushing and grinding characteristics and liberation degree of the ore;

- Correlation of ore characterization with the Pb-Zn flotation circuits tested.

4. Results

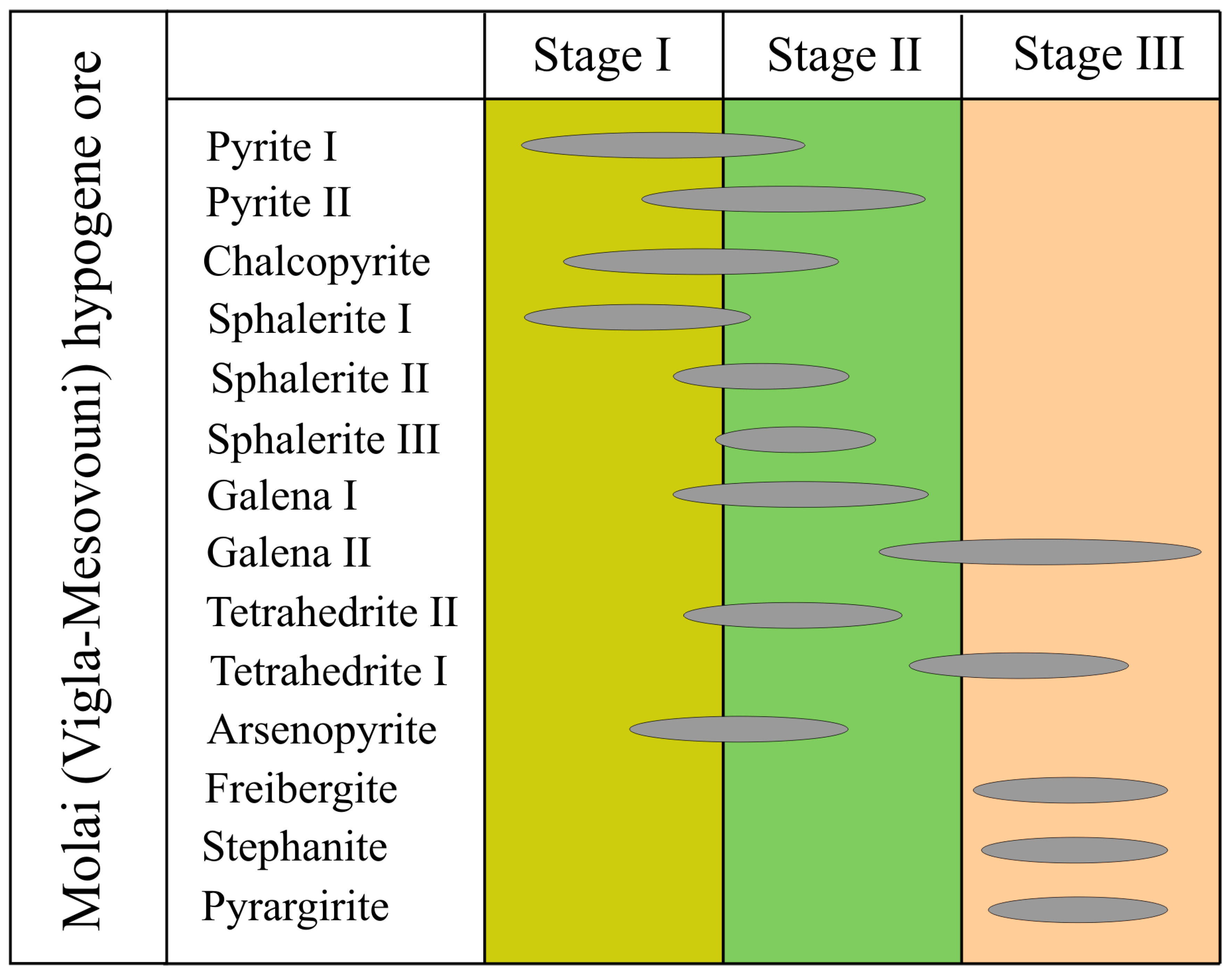

4.1. Mineralogy and Geochemistry of the Bulk Sample

4.2. Chemical Characterization

4.3. Physical and Mechanical Characterization of Ore Phases

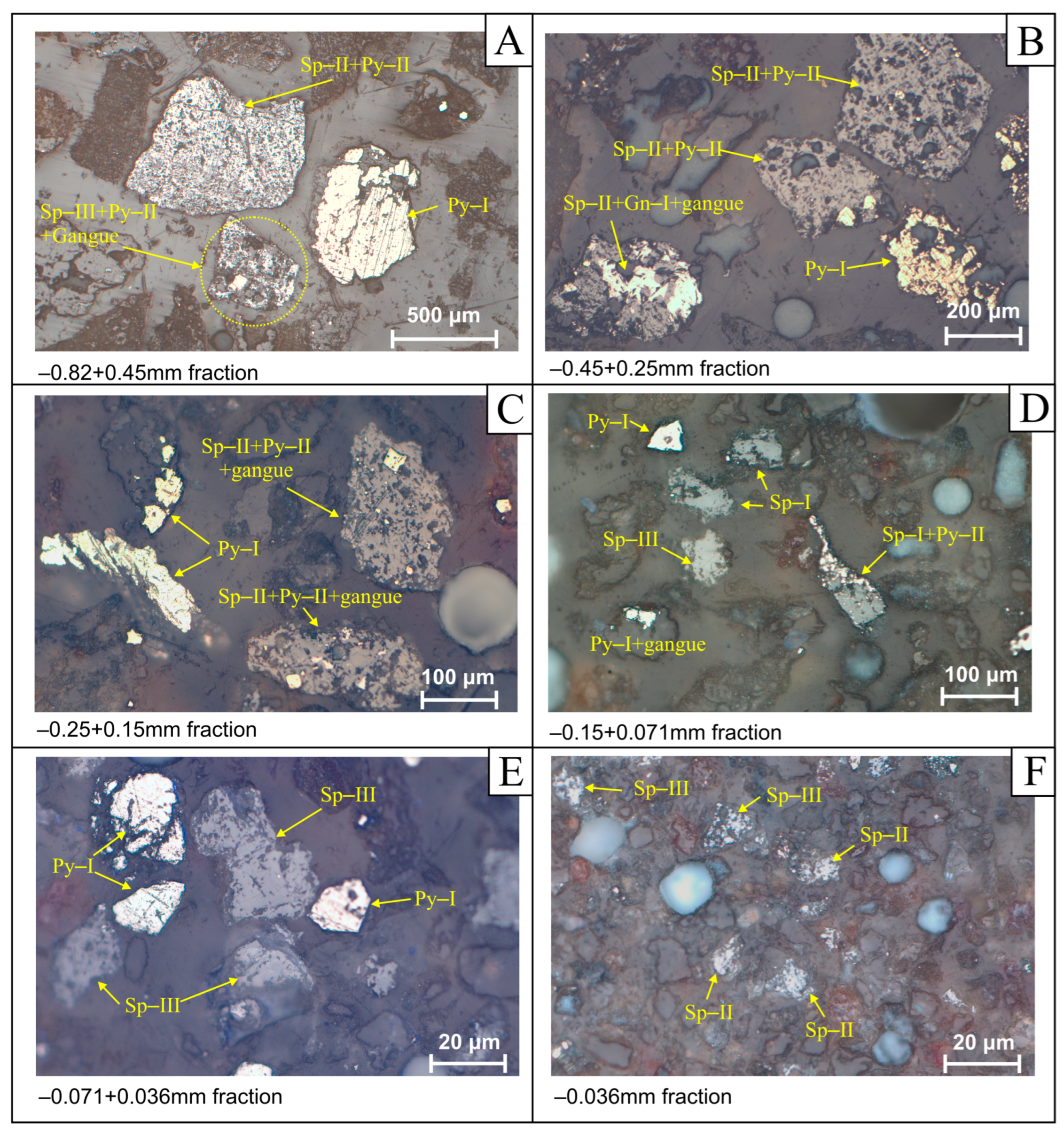

4.4. Crushing, Grinding, Liberation Degree, and Ore Pre-Concentration

4.5. Flotation Circuits

- Mixed (bulk) flotation circuit on finely-ground material (~81% −0.036 mm), designed to separate the ore and obtain a bulk galena–sphalerite concentrate (Table 5; ESM-S3 Table S17).

- Direct differential flotation circuit on finely-ground material (~81% −0.036 mm), designed to provide separate PbS and ZnS concentrates. In this circuit, the pH was the critical factor, with galena floating best around pH = 9, while sphalerite performed best around pH = 11. Additionally, a cleaning stage was incorporated to enhance concentrate quality (Table 5; ESM-S3 Table S18). The Pb concentrate closely met commercial KS4 specifications, while the Zn concentrate exceeded KTs2 quality standards (ESM-S3 Table S1b).

- Combined bulk and differential (mixed) flotation circuit on finely-ground material (~81% −0.036 mm), with one cleaning stage and a scavenger flotation on tailings, designed to provide separate PbS and ZnS concentrates (Table 5; ESM-S3 Table S19). These combined circuits provided zinc concentrate grades exceeding KTs1 metallurgical quality standards (ESM-S3 Tables S1b and S19).

- Flotation circuit on coarse-grained material (~59% −0.036 mm), with a cleaning stage and an additional mixed concentrate from tailings cleaning. Moreover, a combined mixed and differential flotation circuit was also developed (Table 5; ESM-S3 Table S20).

- Flotation circuit on pre-concentrated material from the shaking table. Flotation tests were carried out on a pre-concentrated sample obtained from an initial separation process on the Wilfley shaking table, with the complex flotation circuits, including “middlings”, providing the best overall results (Table 5; ESM-S3 Table S22).

5. Discussion

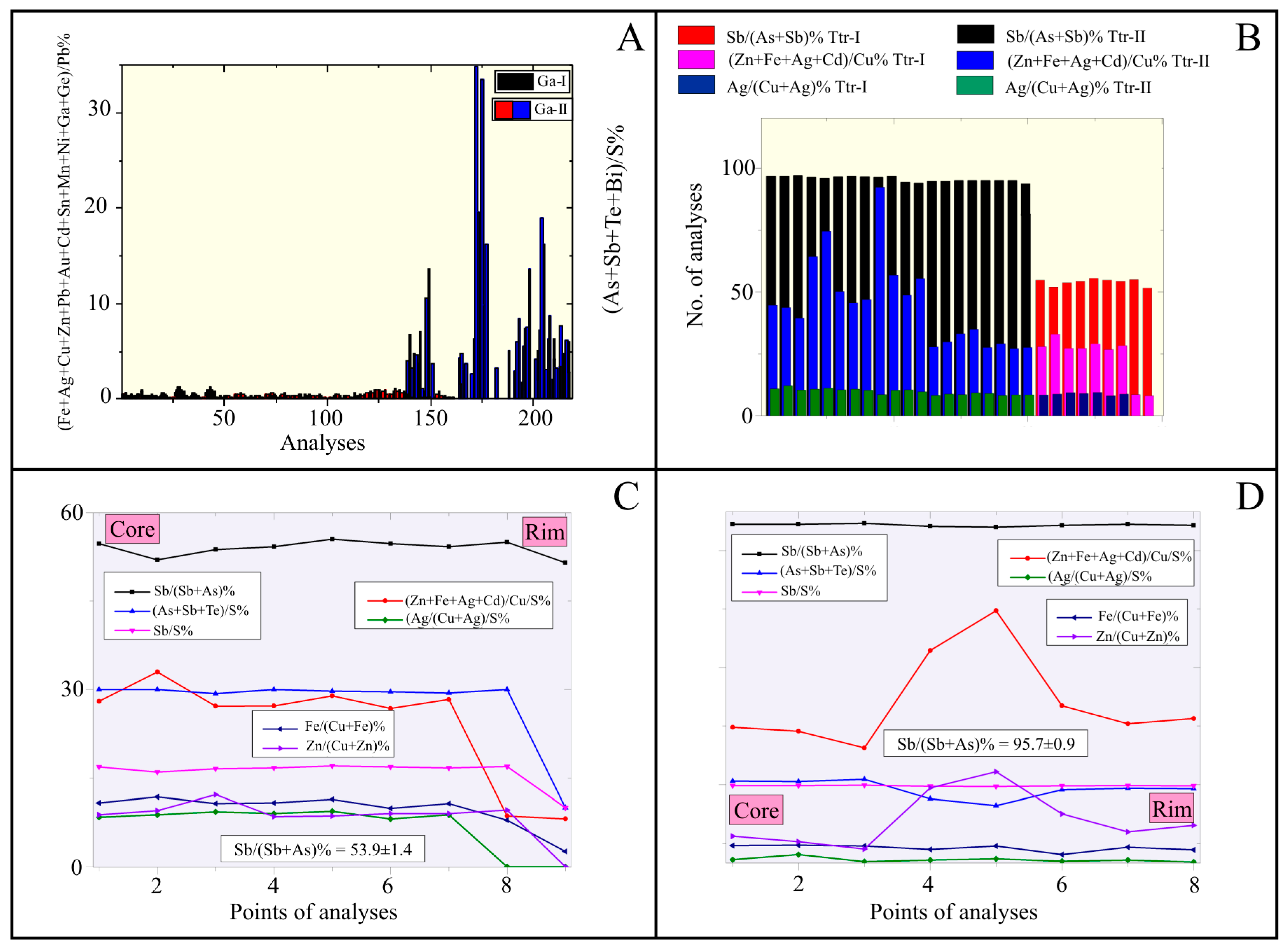

5.1. Ore Characterization—Critical Metal Distribution

5.2. Correlation of Ore Characterization with Beneficiation

6. Conclusions

- The compositional variations identified in the Molai ore depict the evolution of the ore-forming fluids from early-stage and enriched in Ge (±Au, Tl) to later-stage and enriched in Ag and In.

- The distribution of precious and critical metals in the ore phases is complex, and no single phase incorporates each commodity. For instance, Ge is not only present in sphalerite (typical), but also in pyrite (atypical).

- Sphalerite (all varieties) and Py-I govern the distribution of the refractory Ge ore, while Ga-II and Ttr-II define the refractory Ag ore of the Vigla-Mesovouni low-grade sulfide ore. Despite accounting for ~90% and ~58% of concentrate value, respectively, Ge and Ag are hosted in lattice-bound forms, resulting in recovery losses and requiring advanced mineralogical targeting during processing.

- In addition to chemical characteristics, the physical properties of Sp-I and Py-I, such as crystallite size and hardness, play a key role in the design of ore processing routes.

- Py-I and Sp-I, the major Ge-carriers, are easily liberated in the coarse fractions (+0.250 mm and +0.150 mm, respectively), exhibiting crystallite sizes in the range between 55 and 78 μm. The easy liberation of Py-I is directly related to its size and crystal shape in the primary ore, as well as its hardness, thus enhancing its liberation in the coarse fractions (+0.250 mm).

- Pre-concentration prior to flotation tests is essential for producing higher-grade material for feeding into the flotation circuit, particularly for Zn, as pre-concentration may discard ~21% of gangue, enhance downstream flotation performance, concentrate quality, and also reduce downstream processing costs.

- Regarding Pb and Zn, combined flotation circuits on finely ground and pre-concentrated material (−0.036 mm) may produce galena and sphalerite concentrates that meet industrial quality standards.

- Flotation circuits incorporating pH adjustments further enhance recoveries. Galena responds best to ~pH = 9, while sphalerite shows superior floatability at pH = 11.

- Taking into consideration that pyrite (all varieties) is dismissed in the tailings in the flotation circuits tested, it is evident that there is strong potential for Ge recovery from Py-I as a by-product.

- Another late-stage secondary plant should involve the recovery of Ag-rich phases, including Ttr-II, Ga-II, and sulfosalts via selective flotation or pressure oxidation.

- Besides increasing the economic potential of the Molai ore, these secondary flotation circuits also contribute to minimizing the environmental impact of Molai ore during beneficiation, as pyrite and sulfosalts are removed from the tailings.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cox, D.P.; Singer, D.A. Mineral Deposit Models. In U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 1693; U.S. Geological Survey: Preston, VA, USA, 1986; 379p. [Google Scholar]

- John, D.A.; Vikre, P.G.; du Bray, E.A.; Blakely, R.J.; Fey, D.L.; Rockwell, B.W.; Mauk, J.L.; Anderson, E.D.; Graybeal, F.T. Descriptive models for epithermal gold-silver deposits. In U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report, 2010–5070–Q; U.S. Geological Survey: Preston, VA, USA, 2018; 247p. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, B.; Zhang, C.; Yu, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, C.; Ding, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Yand, J.; Xu, Y. Element enrichment characteristics: Insights from element geochemistry of sphalerite in Daliangzi Pb-Zn deposit, Sichuan, Southwest China. J. Geochem. Explor. 2018, 186, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehnavi, A.S.; McFarlane, C.R.M.; Lentz, D.R.; Walker, J.A. Assessment of pyrite composition by LA-ICP-MS techniques from massive sulfide of the Bathurst Mining Camp, Canada: From textural and chemical evolution to its application as a vectoring tool for the exploration of VMS deposits. Ore Geol. Rev. 2018, 92, 656–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winderbaum, L.; Ciobanu, C.L.; Cook, N.J.; Paul, M.; Metcalfe, A.; Gilbert, S. Multivariate Analysis of an LA-ICP-MS Trace Element Dataset for Pyrite. Math. Geosci. 2012, 44, 823–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koski, R.A.; Mosier, D.L. Deposit type and associated commodities. In Volcanogenic Massive Sulfide Occurrence Model; Shanks, W.C.P., III, Thurston, R., Eds.; U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2010–5070–C; U.S. Geological Survey: Preston, VA, USA, 2012; Chapter 2; pp. 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Y.-M.; Huang, X.-W.; Hu, R.; Beaudoin, G.; Zhou, M.-F.; Meng, S. Deposit type discrimination based on trace elements in sphalerite. Ore Geol. Rev. 2024, 165, 105887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, D.; Groves, D.I.; Santosh, M.; Yang, C.-X. Critical metals: Their mineral systems and exploration. Geosystems Geoenvironment 2025, 4, 100323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, N.; Ciobanu, C.L.; George, L.; Zhu, Z.Y.; Wade, B.; Ehrig, K. Trace Element Analysis of Minerals in Magmatic-Hydrothermal Ores by Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry: Approaches and Opportunities. Minerals 2016, 6, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.P.; Shen, J.F.; Li, S.R.; Liu, Y.; Liu, F.X. In—Situ LA-ICP-MS Trace Elements Analysis of Pyrite and the Physicochemical Conditions of Telluride Formation at the Baiyun Gold Deposit, North East China: Implications for Gold Distribution and Deposition. Minerals 2019, 9, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiu, G.; Ghorbani, Y.; Jansson, N.; Wanhainen, C.; Bolin, N.-J. Ore mineral characteristics as rate-limiting factors in sphalerite flotation: Comparison of the mineral chemistry (iron and manganese content), grain size, and liberation. Miner. Eng. 2022, 185, 107705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodenough, K.M. Verplanck and Hitzman: Rare earth and critical elements in ore deposits. Miner. Depos. 2017, 52, 129–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RIMS—Raw Materials Information System. Available online: https://rmis.jrc.ec.europa.eu/rmp/Germanium (RMIS Dashboard) (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Skarpelis, N. Metallogeny of Massive Sulfides and Petrology of the External Metamorphic Belt of the Hellenides (SE Peloponnesus). Ph.D. Thesis, National Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece, 1982. (In Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Grossou-Valta, M.; Adam, K.; Constantinides, D.C.; Prevosteau, J.M.; Dimou, E. Mineralogy of and potential beneficiation process for the Molai complex sulfide orebody, Greece. In Sulfide Deposits-Their Origin and Processing; Gray, P.M.J., Bowyer, G.L., Castle, J.F., Vaughan, D.J., Warner, N.A., Eds.; Institution of Mining and Metallurgy: London, UK, 1990; pp. 119–133. [Google Scholar]

- Kevrekidis, E.; Triantafyllidis, S.S.; Tombros, S.F.; Kokkalas, S.; Papavasiliou, J.; Kappis, K.; Papageorgiou, K.; Koukouvelas, I.; Fitros, M.; Zouzias, D.; et al. Revisiting the concealed Zn-Pb±(Ag, Ge) VMS-style ore deposit, Molai, Southeastern Peloponnese, Greece. Minerals 2024, 14, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockfire Resources. Available online: https://www.rockfireresources.com/projects/molaoi/ (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Grossou-Valta, M.; Mpasios, D.; Charalampidis, P.; Konstantinidou-Vartholomaiou, E. Discussion on the possible treatment of Molai mixed sulphide ore after experimental investigation of typical samples. In Metallurgical Research No. 37; Institute of Geology and Mineral Exploration: Athens, Greece, 1984; E1292; 90p, (In Greek with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Adam, K.; Dimitriadis, D.; Papadimitriou, D.; Stefanakis, M. Applications of hydrometallurgy in processing mixed sulfide concentrates and ores. In Technical Chamber of Greece, Report 892; Scientific Department of Mining and Metallurgical Engineering: Reno, NV, USA, 1986; 86p. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Kelvin, M.; Whiteman, E.; Petrus, J.; Leybourne, M.; Nkuma, V. Application of LA-ICP-MS to process mineralogy: Gallium and germanium recovery at Kipushi Copper-Zinc deposit. Miner. Eng. 2022, 176, 107322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Yang, Z.; Sun, H.; Aka, D.; Koua, K.; Lyu, C. LA-ICP-MS trace element analysis of sphalerite and pyrite from the Beishan Pb-Zn ore district, South China: Implications for ore genesis. Ore Geol. Rev. 2022, 150, 105128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhang, Z.J.; Ulrich, T.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J. Trace element compositions of sulfides from Pb-Zn deposits in the Northeast Yunnan and northwest Guizhou Provinces, SW China: Insights from LA-ICP-MS analyses of sphalerite and pyrite. Ore Geol. Rev. 2022, 141, 104639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Hu, R.; Gao, J.; Leng, C.; Gao, W.; Gong, H. Trace and minor elements in sulfides from the Lengshuikeng Ag-Pb-Zn deposit, South China: A LA-ICP-MS study. Ore Geol. Rev. 2022, 141, 104663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, W. Ore characterization, process mineralogy and lab automation a roadmap for future mining. Miner. Eng. 2014, 60, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, A.R.; Dehaine, Q.; Menzies, A.H.; Michaux, S.P. Characterization of Ore Properties for Geometallurgy. Elements 2023, 19, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiebault, F.; Triboulet, C. Alpine metamorphism and de- formation in Phyllites Nappes (External Hellenides, Southern Peloponnesus, Greece): Geodynamic implications. J. Geol. 1984, 92, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheuz, P.; Krenn, K.; Fritz, H.; Kurz, W. Tectonometamorphic evolution of blueschist-facies rocks in the Phyllite-Quartzite Unit of the External Hellenides (Mani, Greece). Austrian J. Earth Sci. 2015, 108, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, A.H.F. Sedimentary evidence from the south Mediterranean region (Sicily, Crete, Peloponnese, Evia) used to test alternative models for the regional tectonic setting of Tethys during Late Palaeozoic–Early Mesozoic time. In Tectonic Development of the Eastern Mediterranean Region; Robertson, A.H.F., Mountrakis, D., Eds.; The Geological Society of London: London, UK, 2006; Spec Publ 260; pp. 91–154. [Google Scholar]

- Zulauf, G.; Dörr, W.; Xypolias, P.; Gerdes, A.; Kowakczyk, G.; Linckens, J. Triassic evolution of the western Neotethys: Constraints from microfabrics and U–Pb detrital zircon ages of the Plattenkalk Unit (External Hellenides, Greece). Int. J. Earth Sci. 2019, 108, 2493–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pe-Piper, G.; Piper, D.J.W. The Igneous Rocks of Greece: The Anatomy of an Orogen; Gebrüder Borntraeger: Stuttgart, Germany, 2002; 573p. [Google Scholar]

- Sammas, E. Contribution in the enrichment of the mixed sulfide ore from Molai. Ph.D. Thesis, Section of Metallurgy and Materials Technology, School of Mining and Metallurgical Engineering, Athens, Greece, 2018; 239p. (In Greek with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Whitney, D.L.; Evans, B.W. Abbreviations for names of rock-forming minerals. Am. Mineral. 2010, 95, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, S.; Sugaki, A. Phase relations in the Cu-Fe-Zn-S system between 500° and 300 °C under hydrothermal conditions. Econ. Geol. 1985, 80, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaleb, A.M.; Ahmed, A.Q. Structural, electronic, and optical properties of sphalerite ZnS compound calculated using density functional theory (DFT). Chalcogenide Lett. 2022, 19, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabri, L.J. New data on phase relations in the Cu-Fe-S System. Econ. Geol. 1973, 68, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrouvel, C.; Eon, J. Understanding the Surfaces and Crystal Growth of Pyrite FeS2. Mater. Res. 2019, 22, e20171140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullerud, G. The lead-sulfur system. Am. J. Sci. 1969, 267, 233–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renock, D.; Becker, U. A first principles study of coupled substitution in galena. Ore Geol. Rev. 2011, 42, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagioni, C.; George, L.L.; Cook, N.J.; Makovicky, E.; Moëlo, Y.; Pasero, M.; Sejkora, J.; Stanley, C.J.; Welch, M.D.; Bosi, F. The tetrahedrite group: Nomenclature and classification. Am. Mineral. 2020, 105, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Gu, X.; Yang, B.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Z.; Shu, Z.; Dick, J.; Lu, A. Mineralogical characteristics and photocatalytic properties of natural sphalerite from China. J. Environ. Sci. 2019, 89, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, G.; Kaur, M.; Thakur, A.; Kumar, A. Recent Progress on Pyrite FeS2 Nanomaterials for Energy and Environment Applications: Synthesis, Properties and Future Prospects. J. Clust. Sci. 2020, 31, 899–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Földvári, M. Handbook of Thermogravimetric System of Minerals and Its Use in Geological Practice; Geological Institute of Hungary: Budapest, Hungary, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wills, B.A.; Napier-Munn, T. Mineral Processing Technology. An Introduction to the Practical Aspects of Ore Treatment and Mineral, 7th ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mondillo, N.; Arfè, G.; Herrington, R.; Boni, M.; Wilkinson, C.; Mormone, A. Germanium enrichment in supergene settings: Evidence from the Cristal nonsulfide Zn prospect, Bongará district, northern Peru. Miner. Depos. 2018, 53, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Yamaguchi, M. Resonant Raman scattering in GeS2. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1998, 227–230, 757–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, J.; Mosser-Ruck, R.; Caumon, M.C.; Rouer, O.; Andre-Mayer, A.S.; Cauzid, J.; Peiffert, C. Trace element distribution (Cu, Ga, Ge, Cd, and Fe) in sphalerite from the Tennessee MVT deposits, USA, by combined EMPA, LA-ICP-MS, Raman spectroscopy, and crystallography. Can. Mineral. 2016, 54, 1261–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Ye, L.; Hu, Y.; Danyushevskiy, L.; Li, Z.; Huang, Z. Distribution and occurrence of Ge and related trace elements in sphalerite from the Lehong carbonate-hosted Zn-Pb deposit, northeastern Yunnan, China: Insights from SEM and LA-ICP-MS studies. Ore Geol. Rev. 2019, 115, 103175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spasevska, H.; Kitts, C.; Ancora, C.; Ruani, G. Optimized In2S3 thin films deposited by spray pyrolysis. Int. J. Photoenergy 2012, 2012, 637943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Lee, M.S. A Review on Germanium Resources and its Extraction by Hydrometallurgical Method. Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. Rev. 2021, 42, 406–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijlen, W.; Banks, D.A.; Muchez, P.; Stensgard, B.M.; Yardley, B.W.D. The Nature of Mineralizing Fluids of the Kipushi Zn-Cu Deposit, Katanga, Democratic Repubic of Congo: Quantitative Fluid Inclusion Analysis using Laser Ablation ICP-MS and Bulk Crush-Leach Methods. Econ. Geol. 2008, 103, 1459–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osadchii, G.E.; Gorbaty, Y.E. Raman spectra and unit cell parameters of sphalerite solid solutions (FexZn1−xS). Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2010, 74, 568–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzatu, T.; Popescu, G.; Birloaga, I.; Săceanu, S. Study concerning the recovery of zinc and manganese from spent batteries by hydrometallurgical processes. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.M.; Reynolds, R.C., Jr. X-Ray Diffraction and Identification and Analysis of Clay Minerals, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; 378p. [Google Scholar]

- Woodhead, J.D.; Hellstrom, J.; Hergt, J.M.; Greig, A.; Maas, R. Isotopic and Elemental Imaging of Geological Materials by Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry. Geostand. Geoanalytical Res. 2007, 31, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, C.; Hellstrom, J.; Paul, B.; Woodhead, J.; Hergt, J. Iolite: Freeware for the visualization and processing of mass spectrometric data. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2011, 26, 2508–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, C.J.; Dubé-Loubert, H.; Pagé, P.; Barnes, S.J.; Roy, M.; Savard, D.; Cave, B.; Arguin, J.P.; Mansur, E.T. Applications of trace element chemistry of pyrite and chalcopyrite in glacial sediments to mineral exploration targeting: Example from the Churchill Province, northern Quebec, Canada. J. Geoch Expl. 2018, 196, 105–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, D.; Griffin, W.L.; Pearson, N.J.; Powell, W.; Wieland, P.; O’Reilly, S.Y. Trace element partitioning in mixed-habit diamonds. Chem. Geol. 2013, 355, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, N.L. IMA-CNMNC approved mineral symbols. Miner. Mag. 2021, 85, 291–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cases, J.M. Finely Disseminated Complex Sulphide Ores. In Complex Sulphide Ores; Jones, M.J., Ed.; Transactions IMM: London, UK, 1980; p. 234. [Google Scholar]

- Bérubé, M.A.; Marchand, J.C. Evolution of the mineral liberation characteristics of an iron ore undergoing grinding. Int. J. Miner. Process. 1984, 13, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glembotskii, V.A.; Klassen, V.I.; Plaksin, I.N. Flotation; Rabinovich, H.S., Ed.; Hammond, R.E., Translator; Primary Sources: New York, NY, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Marabini, A.; Barbaro, M. Chelating reagents for flotation of sulphide minerals. In Sulphide Deposits—Their Origin and Processing; Transactions IMM: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Wrobel, S.A. Flotation Frothers, Their Action, Composition Properties and Structure. In Proceedings of the “Recent Developments in Mineral Dressing Symposium”, London, UK, 23–25 September 1953; Institution of Mining and Metallurgy (IMM): Carlton South, Australia, 1953; p. 211. [Google Scholar]

- Arnaud, M.; Partyka, S.; Cases, J.M. Ethylxanthate adsorption onto galena and sphalerite. Coll. Surf. 1989, 37, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marabini, A.; Cozza, C. Determination of lead ethylxanthate on mineral surface by IR spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta 1983, 388, 215. [Google Scholar]

- Girczys, J.; Laskowski, J.S. Mechanism of Flotation of Unactivated Sphalerite with Xanthates. Trans. IMM 1972, 81, C118. [Google Scholar]

- Marabini, A.M.; Rinelli, G. Flotation of lead-zinc ores. In Proceedings of the Advances in Mineral Processing, Processing Symposium Honoring N. Arbiter, New Orleans, LA, USA, 3–5 March 1986; pp. 269–288. [Google Scholar]

- Bulatovic, S.M. Flotation of Sulfide Ores. In Handbook of Flotation Reagents Chemistry, Theory and Practice, 1st ed.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2007; ISBN 9780080471372. [Google Scholar]

| Sample | Cal | Ep | Py | Ser | Qz | Ab | Or | Hem | Chl | Ge-Enriched Ore/Gangue | Crystallite Size (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MO10a | 2.4 | 1.3 | 2.3 | 47.5 | 34.7 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 3.3 | 6.7 | 5.93 | 68.3 |

| MO12 | 4.3 | 2.5 | 1.9 | 39.3 | 40.8 | 2.0 | 3.5 | 0.4 | 5.3 | 2.33 | - |

| MO8c | 4.8 | 3.7 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 26.1 | 21.3 | 1.1 | 3.1 | 35.3 | 5.90 | 78.9 |

| MO8d | 3.5 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 20.4 | 28.6 | 26.5 | 4.6 | 3.6 | 10.1 | 5.20 | 72.3 |

| MO4 | 10.3 | 7.3 | 4.9 | 5.9 | 32.5 | 15.6 | 6.3 | 2.8 | 14.5 | 8.26 | 69.8 |

| B56a | 3.5 | 24.8 | 1.1 | 39.7 | 13.5 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 3.1 | 12.3 | 4.38 | 54.7 |

| MO17 | 8.7 | 4.7 | 1.5 | 12.5 | 49.5 | 11.5 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 10.5 | 2.25 | 50.2 |

| MO12 | 6.8 | 8.9 | 2.2 | 1.3 | 36.0 | 40.6 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.35 | 71.1 |

| AN22a | 6.4 | 17.6 | 0.7 | 9.9 | 44.7 | 2.5 | 3.3 | 2.5 | 12.5 | 3.36 | 78.2 |

| AN22g | 3.8 | 34.7 | 0.9 | 11.5 | 24.3 | 6.5 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 16.3 | 1.75 | - |

| AN22f | 4.5 | 30.1 | 1.4 | 24.5 | 21.9 | 3.1 | 4.5 | 2.1 | 8.3 | 3.54 | - |

| AN22a | 5.1 | 19.8 | 4.7 | 8.9 | 35.4 | 4.1 | 2.7 | 5.4 | 14.1 | 11.21 | - |

| AN22b | 4.6 | 12.3 | 3.3 | 27.2 | 35.4 | 7.7 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 4.6 | 6.10 | - |

| AN22c | 3.7 | 10.6 | 2.4 | 13.7 | 25.9 | 2.7 | 3.6 | 1.3 | 36.3 | 3.79 | - |

| AN22e | 6.2 | 5.4 | 3.0 | 27.9 | 31.3 | 7.0 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 15.2 | 5.42 | - |

| Descriptive Statistics | |||||||||||

| Min | 2 | 1 | 1 | 14 | 1 | - | - | 2 | |||

| Max | 10 | 35 | 47 | 49 | 41 | 6 | 5 | 36 | |||

| M | 5.24 | 12.33 | 19.48 | 32.01 | 10.26 | 2.53 | 2.31 | 13.58 | |||

| SD | 2.12 | 10.72 | 14.41 | 9.18 | 11.33 | 1.76 | 1.34 | 9.93 | |||

| Sample MO10 | |||||||||||

| Ore phase | Sp-I | Py-I | Ccp | Mag | Gn-I | GOF A | |||||

| Bulk sample mean (wt.%) | 66.5 | 19.5 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 9.5 | 2.1 | |||||

| Bulk sample S.D. (wt.%) | 3.7 | 4.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 2.4 | ||||||

| Sample MO12 | Min | Max | M | SD | |||||||

| Vickers Hardness Number (VHN) | |||||||||||

| Py-I | 1501.00 | 1545.60 | 1522.50 | 11.52 | |||||||

| Sp-I | 207.48 | 226.50 | 216.67 | 7.07 | |||||||

| Young’s modulus (E) | |||||||||||

| Py-I | 136.69 | 140.87 | 138.93 | 1.14 | |||||||

| Sp-I | 70.37 | 77.54 | 73.93 | 2.35 | |||||||

| Sample (MO10) | SSA (m2/g) | Pore Volume (cm3/g) | Pore Size (nm) | dhkl (nm) B,C | |||||||

| Py-I | 10.49 | 0.0072 | 1.713 | 64.3 ± 8.1 | |||||||

| Sp-I | 1.43 | 0.0023 | 1.889 | 75.1 ± 4.1 | |||||||

| Sample | MO10 (B25-88) (1) | MO12 (2) | MO18 (B25 91-40) (3) | Mixed Sulfide Ore Used in Beneficiation (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major elements (wt.%) | ||||

| SiO2 | 40.14 | 43.47 | 43.85 | 43.5 |

| TiO2 | 0.55 | 0.32 | 0.74 | NA |

| Al2O3 | 6.55 | 6.03 | 9.19 | 6.0 |

| Fe2O3T | 7.17 | 4.85 | 4.96 | 6.9 |

| MnO | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.029 | NA |

| MgO | 0.35 | 0.52 | 0.53 | 5.2 |

| CaO | 0.85 | 10.53 | 2.82 | 10.5 |

| Na2O | 0.05 | 0.32 | 0.48 | 0.3 |

| K2O | 2.26 | 1.59 | 2.99 | NA |

| P2O5 | 0.12 | NA 1 | 0.19 | NA |

| SO2 | 5.43 | 5.29 | 4.67 | 10.4 |

| LOI | 9.56 | 6.78 | 7.66 | 6.7 |

| Total | 73.04 | 79.72 | 78.12 | 89.5 |

| Trace elements (ppm) | ||||

| Co | 9 | NA | 19 | NA |

| Ni | 18 | NA | 16 | NA |

| Cu | 140 | 598 | 210 | 600 |

| Zn | 58,545 | 63,451 | 60,768 | 63,400 |

| Cd | 34 | 42 | 41 | 40 |

| Ga | 25 | NA | 21 | NA |

| Ge | 95 | NA | 38 | NA |

| As | 212 | NA | 227 | NA |

| Ag | 23.6 | 34.7 | 15.9 | 35 |

| In | 0.4 | NA | 0.15 | NA |

| Sb | 71.3 | NA | 77.7 | NA |

| La | 11 | NA | 13.2 | NA |

| Ce | 23.9 | NA | 31.7 | NA |

| Tl | 0.8 | NA | 0.7 | NA |

| Pb | 11,204 | 11,242 | 10,956 | 11,200 |

| Bi | 0.23 | NA | 0.36 | NA |

| Min | Max | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn (Sp-I) | 4.30 | 518.40 | 95.65 | 207.14 |

| Mn (Sp-II) | 3.20 | 13.00 | 9.78 | 2.61 |

| Mn (Sp-III) | 2.10 | 929.20 | 137.32 | 298.39 |

| Co (Sp-I) | 0.60 | 36.70 | 6.96 | 14.58 |

| Co (Sp-II) | b.d.l. | 2.40 | 0.88 | 0.54 |

| Co (Sp-III) | 0.20 | 15.30 | 4.86 | 6.62 |

| Cu (Sp-I) | 233.00 | 3554.90 | 1271.92 | 1254.55 |

| Cu (Sp-II) | 78.90 | 4427.00 | 1339.61 | 1092.10 |

| Cu (Sp-III) | 200.80 | 1931.70 | 936.11 | 639.31 |

| Ga (Sp-I) | b.d.l. | 85.47 | 16.15 | 34.24 |

| Ga (Sp-II) | b.d.l. | 12.31 | 4.36 | 4.25 |

| Ga (Sp-III) | 5.30 | 83.50 | 26.46 | 27.83 |

| Ge (Sp-I) | 44.80 | 1891.60 | 610.67 | 670.74 |

| Ge (Sp-II) | 23.50 | 578.80 | 277.03 | 178.63 |

| Ge (Sp-III) | 61.20 | 656.70 | 267.48 | 222.39 |

| Ag (Sp-I) | 149.90 | 809.50 | 388.15 | 212.68 |

| Ag (Sp-II) | 59.00 | 2694.00 | 733.47 | 671.08 |

| Ag (Sp-III) | 112.50 | 3263.80 | 785.15 | 1229.91 |

| Cd (Sp-I) | 8651.70 | 21,255.50 | 11,954.57 | 4764.84 |

| Cd (Sp-II) | 7266.40 | 16,412.70 | 10,592.31 | 2694.32 |

| Cd (Sp-III) | 10,242.60 | 16,786.80 | 12,353.02 | 2432.28 |

| In (Sp-I) | b.d.l. | 0.50 | 0.09 | 0.21 |

| In (Sp-II) | b.d.l. | 0.20 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| In (Sp-III) | b.d.l. | 1.10 | 0.23 | 0.39 |

| Sn (Sp-I) | b.d.l. | 3.50 | 1.22 | 1.32 |

| Sn (Sp-II) | b.d.l. | 1.40 | 0.72 | 0.46 |

| Sn (Sp-III) | b.d.l. | 2.40 | 1.20 | 0.69 |

| Tl (Sp-I) | b.d.l. | 116.20 | 19.53 | 47.36 |

| Tl (Sp-II) | b.d.l. | 1.30 | 0.36 | 0.36 |

| Tl (Sp-III) | b.d.l. | 18.90 | 4.51 | 7.41 |

| Pb (Sp-I) | 61.40 | 6504.90 | 1219.75 | 2590.65 |

| Pb (Sp-II) | 37.80 | 10,799.30 | 1238.96 | 2635.41 |

| Pb (Sp-III) | b.d.l. | 2718.10 | 1029.60 | 994.92 |

| As (Sp-I) | 7.40 | 2898.60 | 524.67 | 1163.62 |

| As (Sp-II) | 4.60 | 376.70 | 93.29 | 92.77 |

| As (Sp-III) | 7.40 | 1656.10 | 396.40 | 611.23 |

| Se (Sp-I) | b.d.l. | 15.30 | 2.55 | 6.25 |

| Se (Sp-II) | b.d.l. | 1.50 | 0.09 | 0.37 |

| Se (Sp-III) | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. |

| Sb (Sp-I) | 123.20 | 1362.30 | 596.58 | 443.98 |

| Sb (Sp-II) | 76.40 | 7141.10 | 1447.07 | 1666.55 |

| Sb (Sp-III) | 86.70 | 1096.00 | 380.54 | 300.23 |

| Te (Sp-I) | b.d.l. | 1.00 | 0.16 | 0.40 |

| Te (Sp-II) | b.d.l. | 0.50 | 0.03 | 0.11 |

| Te (Sp-III) | b.d.l. | 0.56 | 0.06 | 0.18 |

| Bi (Sp-I) | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. |

| Bi (Sp-II) | b.d.l. | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Bi (Sp-III) | b.d.l. | 0.03 | b.d.l. | 0.01 |

| Variety | Sp-I | Sp-II | Sp-III | |

| XFeS (molar) | 20.5 ± 2.7 | 6.3 ± 1.7 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | |

| Fe/S | 0.229 ± 0.04 | 0.062 ± 0.01 | 0.0075 ± 0.004 | |

| Zn/S | 0.79 ± 0.06 | 0.77 ± 0.04 | 0.97 ± 0.01 | |

| A * | 26.7 ± 4.7 | 6.5 ± 1.5 | 0.94 ± 0.45 | |

| B ** | 0.03 ± 0.98 | 0.66 ± 0.81 | - |

| Min | Max | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn (Py-I) | 633 | 1435 | 939.90 | 362.60 |

| Mn (Py-II) | 739 | 1433 | 1079.20 | 313.67 |

| Co (Py-I) | 487 | 1112 | 773.08 | 257.01 |

| Co (Py-II) | 402 | 1204 | 686.28 | 372.38 |

| Cu (Py-I) | 6019 | 13,723 | 9079.50 | 3288.87 |

| Cu (Py-II) | 4961 | 12,304 | 8410.74 | 3382.24 |

| Ga (Py-I) | 6 | 19 | 12.92 | 5.10 |

| Ga (Py-II) | 4 | 55 | 18.13 | 24.66 |

| Ge (Py-I) | 81 | 383 | 204.52 | 144.08 |

| Ge (Py-II) | 102 | 188 | 149.85 | 36.47 |

| Ag (Py-I) | 2 | 6 | 3.54 | 1.68 |

| Ag (Py-II) | 3 | 4 | 3.25 | 0.55 |

| Cd (Py-I) | 7 | 11 | 8.56 | 1.56 |

| Cd (Py-II) | 4 | 24 | 10.90 | 8.82 |

| In (Py-I) | 1 | 2 | 1.14 | 0.59 |

| In (Py-II) | 1 | 1 | 1.08 | 0.21 |

| Au (Py-I) | 86 | 245 | 153.65 | 73.51 |

| Au (Py-II) | 55 | 205 | 110.42 | 72.43 |

| Tl (Py-I) | 4 | 9 | 6.04 | 2.64 |

| Tl (Py-II) | 5 | 9 | 8.55 | 1.91 |

| Pb (Py-I) | 11 | 42 | 22.32 | 11.92 |

| Pb (Py-II) | 14.00 | 20.20 | 17.15 | 3.01 |

| Sb (Py-I) | 15.50 | 39.30 | 24.62 | 11.39 |

| Sb (Py-II) | 19 | 43 | 27.25 | 11.15 |

| Te (Py-I) | 23.70 | 70.30 | 41.14 | 20.29 |

| Te (Py-II) | 32 | 90 | 48.35 | 27.76 |

| Bi (Py-I) | 2.60 | 10.60 | 6.08 | 3.76 |

| Bi (Py-II) | 3 | 9 | 6.20 | 2.79 |

| As (Py-I) | 447.70 | 3142.80 | 1350.44 | 1135.22 |

| As (Py-II) | 591 | 884 | 701.50 | 140.07 |

| Se (Py-I) | 0.22 | 0.58 | 0.38 | 0.15 |

| Se (Py-II) | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 0.13 | 0.06 |

| Py-I | Py-II | |||

| A * | ≤0.5 | ≥0.6 | ||

| B ** | 200–400 | ≤100 | ||

| C *** | 100 | ≤50 |

| Test No. | Product | Weight % | Pb Grade (%) | Zn Grade (%) | Pb Recovery (%) | Zn Recovery (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed (bulk) flotation circuit on finely ground material (~81% < 0.036 mm) | 4 (ESM-S3 Figure S14) | Total concentrate | 15.54 | 6.64 | 35.10 | 86.41 | 90.22 |

| Differential flotation circuit on finely ground material (~81% < 0.036 mm) | 6 (ESM-S3 Figure S15) | Pb concentrate | 3.28 | 30.25 | 2.36 | 82.89 | 1.25 |

| Zn concentrate | 10.48 | 0.47 | 50.80 | 4.11 | 86.13 | ||

| Combined bulk and differential (mixed) flotation circuit on finely ground material (~81% < 0.036 mm) | 14 (ESM-S3 Figure S17) | Pb concentrate | 2.55 | 32.29 | 2.5 | 58.63 | 1.01 |

| Zn concentrate | 8.75 | 0.26 | 57.4 | 1.62 | 79.22 | ||

| Flotation circuit on coarse-grained material (~59% < 0.036 mm) | 19 ESM-S3 Figures S18 and S19) | Pb concentrate | 3.10 | 32.20 | 1.23 | 78.68 | 0.59 |

| Zn concentrate | 8.50 | 0.35 | 62.10 | 2.34 | 81.13 | ||

| Flotation circuit on pre-concentrated material | 20 | Pb concentrate | 5.23 | 20.2 | 2.11 | 80.35 | 1.72 |

| Zn concentrate | 10.25 | 0.25 | 55.23 | 1.95 | 88.27 | ||

| 21 | Pb concentrate | 4.55 | 25.23 | 1.86 | 82.60 | 1.25 | |

| Zn concentrate | 9.66 | 0.28 | 59.65 | 1.65 | 84.88 | ||

| Flotation circuit on pre-concentrated material (mixed) | 22 (ESM-S3 Figure S20) | Pb concentrate | 4.32 | 27.12 | 0.65 | 84.09 | 0.42 |

| Zn concentrate | 10.15 | 0.2 | 56.56 | 1.46 | 86.12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Triantafyllidis, S.S.; Tombros, S.F.; Sammas, E.; Kevrekidis, E.; Kappis, K.; Fitros, M.; Mavrogonatos, C.; Papageorgiou, K.; Spiliopoulou, E.; Kokkalas, S.; et al. Ore Characterization and Its Application to Beneficiation: The Case of Molai Zn-Pb±(Ag,Ge) Epithermal Ore, Laconia, SE Peloponnese, Greece. Minerals 2025, 15, 1152. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111152

Triantafyllidis SS, Tombros SF, Sammas E, Kevrekidis E, Kappis K, Fitros M, Mavrogonatos C, Papageorgiou K, Spiliopoulou E, Kokkalas S, et al. Ore Characterization and Its Application to Beneficiation: The Case of Molai Zn-Pb±(Ag,Ge) Epithermal Ore, Laconia, SE Peloponnese, Greece. Minerals. 2025; 15(11):1152. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111152

Chicago/Turabian StyleTriantafyllidis, Stavros Savvas, Stylianos Fotios Tombros, Elias Sammas, Elias Kevrekidis, Konstantinos Kappis, Michalis Fitros, Constantinos Mavrogonatos, Konstantinos Papageorgiou, Ekaterini Spiliopoulou, Sotirios Kokkalas, and et al. 2025. "Ore Characterization and Its Application to Beneficiation: The Case of Molai Zn-Pb±(Ag,Ge) Epithermal Ore, Laconia, SE Peloponnese, Greece" Minerals 15, no. 11: 1152. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111152

APA StyleTriantafyllidis, S. S., Tombros, S. F., Sammas, E., Kevrekidis, E., Kappis, K., Fitros, M., Mavrogonatos, C., Papageorgiou, K., Spiliopoulou, E., Kokkalas, S., Voudouris, P., Vasilatos, C., Zhai, D., Nikolakopoulos, P., Koukouvelas, I., Papavasiliou, J., & Kalaitzidis, S. (2025). Ore Characterization and Its Application to Beneficiation: The Case of Molai Zn-Pb±(Ag,Ge) Epithermal Ore, Laconia, SE Peloponnese, Greece. Minerals, 15(11), 1152. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111152