Abstract

A carbonate-bearing, fluorine-overcompensated fluorapatite (F = 4.42 wt.% as compared with 3.77 wt.% F in the Ca5(PO4)3F end-member), was identified in forsterite-bearing skarns from Valea Rea (N 46°39′48″, E 22°36′43″), located near the contact of the granodiorite laccolith from Budureasa, of Upper Cretaceous Age, with Anisian dolostones. The chemical structural formula (with carbonate not included) is: (Ca4.989Mn0.001Fe2+0.003Mg0.003Ce0.001La0.001)(P2.992Si0.008)(O11.894F1.202Cl0.001). No major structural distortions due to (CO3F)3--for-(PO4)3- replacement were identified by single crystal X-ray diffraction, Raman or FTIR. The mineral crystallizes in space group P63/m, having as cell parameters a = 9.3818(1) Å and c = 6.8872(1) Å. The indices of refraction are: ω = 1.634(2) and ε = 1.631(1). The calculated density is Dx = 3.199 g/cm3 and the measured density is Dm = 3.201(3) g/cm3. Calculation of the Gladstone–Dale compatibility indices gave in all cases values indicative of superior agreement between physical and chemical data. In the infrared spectra, the multiplicity of the bands assumed to phosphate modes (1ν1 + 2ν2 + 3ν3 + 3ν4) agrees with the reduction of the symmetry of PO43− ion from Td to C6. Chemical peculiarities and textural relations agree with a hydrothermal origin of the mineral, crystallized from F-rich fluids originating from the granodiorite intrusion.

1. Introduction

Fluorapatite, ideally Ca5(PO4)3F, is considered the most stable and widespread mineral in the apatite group (e.g., [1,2,3,4] and references therein). The reason for its higher stability was shown by the thermodynamic analysis of F-Cl-OH partitioning between minerals and hydrothermal fluids. Using this approach, fluorapatite can be shown to equilibrate more easily with the hydrothermal fluids than chlorapatite and hydroxylapatite [5], which implies that most of the hydrothermal apatite is dominantly F-rich. Based on crystal-structure refinements, that the structure of fluorapatite seems the most stable in the apatite group, having a higher symmetry, than the Cl- or (OH)-rich members of the group [6], which supports the mineral abundance in igneous and hydrothermal contexts.

Fluorapatite is consequently the most common phosphate in skarn, skarn deposits and skarn-like rocks. The mineral was mentioned in regional or reaction skarns [7,8], in classic (contact) skarns [9,10] and also in mineralized skarns such as W-Cu ± Au skarns [11,12] or Fe-Cu and base-metal skarns [13,14,15,16]. Only rarely this mineral is visible at macroscopic scale (e.g., [9]). Generally, fluorapatite in skarn and skarn deposits occurs as isolated microcrystals, commonly included in garnet [10] or magnetite [15].

Recent study of magnesian skarns from Valea Rea (Bihor County, Romania) revealed the presence of an unusual F-rich, carbonate-bearing fluorapatite as an abundant phase, prompting this description.

2. Geological Setting

From a geographical point of view, Valea Rea (Rea Valley) is a permanent brook, left affluent of Cohului Valley, in its turn major affluent of Mare Valley, the main affluent of Crişul Negru River. From an administrative point of view, the upper basin of Valea Rea pertains to the hinterland area of Budureasa commune, well known for its sport resort, Stâna de Vale. In its upper basin, the valley crosses intrusive rocks pertaining to the Budureasa laccolith, as well as contact metamorphic rocks (skarns, hornfelses and marbles) from its southeastern contact. The geological map of the area is given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Geological sketch of Budureasa area in regional context: the Banatitic Magmatic and Metallogenetic Belt (top, left: redrawn from [17]) and the structural context of Romania (top, right: from [18], simplified). Redrawn and modified from [19]. Symbols in the legend represent: Arieşeni Nappe: 1—Permian-Scithian (siliciclastic rocks); Ferice Nappe: 2—Scithian (siliciclastic rocks); 3—Anisian (dolostones and dolomitic limestones); 4—Ladinian (limestones); 5—Carnian—Norian (limestones); 6—Rhaetian (limestones); 7—Lower Jurassic (limestones); 8—Cretaceous (calcic-siliciclastic rocks). Banatitic magmatism: 9—Rhyolites-rhyodacites; 10—Granodiorites; 11—Diorites; 12—Vlădeasa rhyolites; 13—Contact area (skarns, hornfelses); 14—Fault; 15—Overthrust line. The star marks the location of Valea Rea gallery.

The Budureasa laccolith (Apuseni Mountains, Bihor Massif) represents the northern occurrence of the huge magmatic body known as “the Bihor Batholith”, probably the most important from metallogenetic point of view in the Banatitic Magmatic and Metallogenetic Belt [20]. This belt, referred to as BMMB, consists in a series of discontinuous magmatic and metallogenetic districts that are discordant over a Middle Cretaceous nappe structure ([17,21,22,23] and references therein): Figure 1. The laccolith from Budureasa consists mainly of granodiorite and granite porphyry with subordinate quartz monzodiorite and diorite [24]. The K-Ar age established on the mafic fraction is of 74 ± 3 Ma [25], in fair agreement with the ages compiled for intrusive rocks of the same batholith, from Pietroasa (73 ± 3 [21]) and Băiţa Bihor (70 ± 5 to 67 ± 3 Ma), but also with the Re-Os ages reported on molybdenite from Băiţa Bihor skarns (80.63 ± 0.3 to 78.69 ± 0.4 Ma: [22]).

The occurrence of magnesian skarn from Valea Rea occurs in the close proximity of the southern contact of the intrusive body with Anisian dolostones pertaining to the Ferice Unit (Figure 1). The skarn, investigated with an exploration mine shaft, is forsterite- and phlogopite-bearing, located near the contact. The coordinates of the shaft entry, dug in the late 1980s and known as “Galeria 2” (“Shaft 2”), are N 46°39′48″, E 22°36′43″. The skarn consists of a mass of forsterite (Fo = 97.28–98.54 mol.%, Fa = 1.46–2.62 mol.%, Tep = 0–0.20 mol.%—symbols for olivine end-members from [26]), occurring as relics in mesh textures of chrysotile and lizardite. Flakes of phlogopite occur in discontinuous bands in the skarn mass. The F/(F + OH) ratio in phlogopite ranges from 0.123 to 0.215.

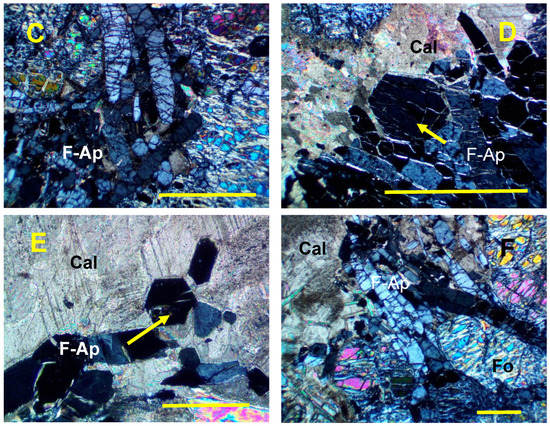

Fluorapatite was identified as swarms of crystals or agglomerations in calcite veins that crosscut the magnesian skarn. Fluorite (Ca0.9984Mn0.001Ni0.001F2) also occurs as isolated pods in the same veins. Textural relations at the level of thin sections show that fluorapatite postdates both phlogopite and forsterite and is contemporaneous or, in some cases, earlier than serpentines and fluorite. The reciprocal relations between minerals associated with fluorapatite and fluorapatite itself are better depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Photomicrographs showing characteristic relationships between fluorapatite and associated minerals in the Valea Rea skarn. Crossed polars. The scale bar on each photograph represents 1 mm. (A). Aggregate of fluorapatite crystals (right) from a vein bordered by forsterite (Fo) with lizardite (Lz) veins. Sample 908. (B). Veins of fluorapatite (F-Ap) enclosing forsterite (Fo) crystals altered by serpentine-group minerals. Sample 908. (C). Detail of a fluorapatite (F-Ap) vein in the forsterite-bearing skarn. Sample 908. (D). Detail on a fluorapatite (F-Ap) vein overgrown by calcite (Cal) in the forsterite-bearing skarn. The arrow indicates a nearly basal section. Sample 909. (E). Vein of fluorapatite (F-Ap) in the calcite (Cal) mass. The arrow indicates a basal section. Sample 909. (F). Fluorapatite vein at the limit of forsterite-bearing skarn with the Mg-depleted dolomitic limestone (Cal). Fluorapatite (F-Ap) enclose forsterite relics (Fo). Sample 909. Symbols for the rock-forming minerals after [26].

3. Materials and Methods

Electron-microprobe analyses (EMPA) were performed using a CAMECA SX-50 apparatus (CAMECA, Gennevilliers, Ile-de-France, France), hosted by the Paris VI Universityoperating on wavelength-dispersive spectrometry. The apparatus was set at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV and a beam current of 10 nA (measured at the Faraday cup), and a beam diameter of 10 µm. Natural diopside (Si, Mg and Ca Kα), synthetic hematite (Fe Kα), natural orthoclase (K and Al Kα), natural albite (Na Kα), natural pyrophanite (Ti and Mn Kα), synthetic Ca-Al-REE silicate glasses (La and Ce Kα), natural apatite (P Kα), natural sodalite (Cl Kα) and synthetic sellaite (F Kα) served as standards. Counting time was 10 s per element. Data were reduced and corrected using the PAP procedure [27]. During the analysis, recommendations by [28] concerning the EMPA analysis of apatite-group minerals (i.e., first-time exposure of the sample to the electron beam, low counting times, analysis with priority of the least-stable primary components, including halogens, analyses on crystals with different crystallographic orientations) were carefully respected. S and Sr were sought, but not detected. The standards used in their cases were natural lazurite and natural celestine, respectively.

High-resolution SEM images were obtained at the Geological Institute of Romania, using a Hitachi TM3030 tabletop scanning electron microscope (Chiyoda, Tokyo, Japan), with improved electron optical system, operated at 5 kV acceleration voltage.

In the case of the sample 908, the powder-diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed on a Siemens D-5000 Kristalloflex automated diffractometer (Siemens, Karlsruhe, Germany) equipped with a graphite diffracted-beam monochromator (CuKα radiation, λ = 1.54056 Å), at Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Mines de Saint Etienne (France). The apparatus was operated at a scan speed of 0.02° 2θ per second, with a time per step of 2 s. The XRD pattern of the sample 909 was recorded using a Brucker (AXS) D8 Advance diffractometer (Karlsruhe, Germany) hosted by the Geological Institute of Romania (Bucharest). The apparatus used Ni-filtered CuKα radiation, a step size of 0.02° 2θ, and a counting time of 6 s per step. An operating voltage of 40 kV for a current of 30 mA, a slit system of 1/0.1/1 with a receiving slit of 0.6 mm, and a scanning range of 4 to 100° 2θ were used for all measurements. For both samples, the unit-cell parameters were calculated by least-squares refinement of the XRD data, using the computer program of [29] modified for microcomputer use [30]. Synthetic silicon (NBS 640b) was used as an external standard in order to verify the accuracy of the measurements.

Structure refinements were based on single-crystal X-ray diffraction. The data were collected at room temperature with monochromatized MoKα radiation (λ = 0.71703 Å) at 50 kV and 1 mA, on a Rigaku XtaLAB Synergy-S diffractometer equipped with a HyPix-6000He detector (both manufactured in Osaka, Japan) housed at Natural History Museum in Oslo, Norway. The instrument has Kappa geometry and both data collection and subsequent data reduction and face based absorption corrections were carried out using the CrysAlis Pro software [31]. The initial solution of the structure in space group P63/m was determined by the charge flipping method using the Superflip algorithm [32], and the structural model was subsequently refined on the basis of F2 with the Jana2006 software [33].

The infrared absorption spectrum was obtained using a Fourier-transform THERMO Nicolet Nexus spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Madison, WI, USA), hosted by the Geological Institute of Romania, in the frequency range between 400 and 4000 cm−1, using a standard pressed-disk technique, after embedding 2 mg of mechanically ground mineral powder in 148 mg of dry KBr and compacting under 2500 N/cm2 pressure. The spectral resolution was 0.1 cm−1. The spectrum was recorded at 25 °C. The material to be analyzed was carefully hand-picked after etching with 0.1 M acetic acid (pH = 2.88), and the final purity was checked by X-ray powder diffractometry.

Raman spectra were recorded using a Renishaw SEM-Raman system (Artisan Scientific, Champaign, IL, USA) hosted by the Geological Institute of Romania, at 25 °C, using both structural and chemical analysis (SCA) and inVia interfaces. The spectrometer was equipped with a 100 mW, 532 nm Ar laser as excitation source. The spectral resolution was 1 cm−1 for a 1 μm spatial resolution. The spectra were collected using a 50x objective, a confocal aperture of 400 µm, a 150 µm slit width, and 1800 lines·mm−1 grating, in the range of 200–2100 cm−1 (10-s accumulation time, 3 scans). The instrument was calibrated with synthetic silicon and stoichiometric fluorapatite.

Indices of refraction were measured at room temperature (25 °C), using the Becke-line method and monochromatic (Na) light (λ = 589 nm), by immersion in Cargille oils, using a spindle stage and a JENAPOL-U microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

The mean density of carefully hand-picked fluorapatite from Valea Rea (Sample 908) was measured by the sink-float method, at 25 °C, using a mixture of methylene iodide and toluene as immersion liquid.

UV-luminescence tests were performed using a portable Vetter ultraviolet lamp (Vetter, Lottstetten, Germany) with 254 and 366 nm filters.

4. Crystal Morphology

At Valea Rea, fluorapatite occurs as infillings of calcite-apatite veins which can be easily distinguished in the mass of magnesian skarn because of their lighter color. Minor fluorite was also identified in these veins. Fluorapatite occurs as agglomerations of euhedral crystals, with columnar habit, of up to 1 mm in length and 0.3 mm in width, generally surrounded by calcite.

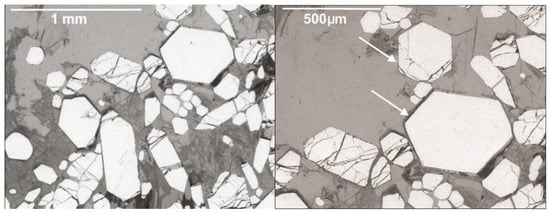

Transversal sections of typical crystals of fluorapatite from Valea Rea are given in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

SEM microphotographs of typical sections on fluorapatite crystals. The arrows indicate basal or nearly basal (001) sections.

They define individual crystals as long prismatic on [0001], having a simple combination of forms consisting of prisms {100} and low pyramids {101} (notation using Bravais indices). Transversal sections, as well as geometrical goniometry on isolated crystals allowed the exact measurement of the angles between the prism and pyramid faces. A similar crystal shape, better depicted in Figure 4, was described for fluorapatite from Ocna de Fier skarn [9]. No twinning was identified.

Figure 4.

Sketch of a fluorapatite crystal showing the crystal shape, consisting in a combination of “m” low pyramid faces (101) and “p” (10 0) prisms.

5. Structure

The structural refinement of a representative sample of fluorapatite from Valea Rea (Sample 908 A) was done in order to supplement the data on minerals. The details of the data collection and refinement are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Details of the X-ray data collection and refinements of fluorapatite, Valea Rea.

Table 5.

Detailed bond-valence table (vu) for the crystal structure of fluorapatite, Valea Rea.

Table 4.

Bond distances (Å) observed in the crystal structure of fluorapatite, Valea Rea.

Table 3.

Anisotropic displacement parameters (Å2) for fluorapatite, Valea Rea.

Table 2.

Atom coordinates and isotropic displacement parameters (Å2) for fluorapatite, Valea Rea.

Table 1.

Details of the X-ray data collection and refinements of fluorapatite, Valea Rea.

| Crystal data | |

| Crystal shape | Prismatic-bipyramidal |

| Color | colorless |

| Crystal size (mm3) | 0.11 × 0.07 × 0.03 |

| Temperature (K) | 293(2) |

| a (Å) | 9.3818(1) |

| c (Å) | 6.8872(1) |

| γ (°) | 120.00 |

| V (Å3) | 524.983(11) |

| Space group | P63/m |

| Z | 2 |

| Dcalc. (g/cm3) | 3.190 |

| Data collection | |

| Absorption coefficient (mm−1) | 3.094 |

| F(000) | 500 |

| Max. 2θ (°) | 71.66 |

| Range of indices | −15 < h < 15 −15 < k < 15 −11 < l < 11 |

| Number of measured reflections | 51,825 |

| Number of unique reflections | 858/797 |

| Criterion for observed reflections | I > 3σ(I) |

| Refinement | |

| Refinement on | Full-matrix least squares on F2 |

| Number of refined parameters | 39 |

| R1(F) with F0 > 4s(F0) * | 0.0156 |

| R1(F) for all the unique reflections * | 0.0173 |

| wR2(F2) * | 0.0574 |

| Rint(%) | 0.0474 |

| S (“goodness of fit”) | 1.00 |

| Weighing scheme | 1/(σ2(I)2 + 0.0025(I)2 |

| Min./max. residual e density, (eÅ−3) | −0.32, 0.33 |

* Notes: R1 = Σ(|Fobs|–|Fcalc|)/Σ|Fobs|; wR2 = {Σ[w(F2obs–F2calc)2]/Σ[w(F2obs)2]}0.5 The structure was refined to R = 0.017 as compared with R = 0.025 [6]. All atoms were refined with anisotropic thermal parameters; those parameters, as well as the atoms coordinates, are provided in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5.

Free refinement of the occupancy factors of the cationic sites indicated that they are fully occupied. The bond distances and bond-valence sums are given in Table 4 and Table 5. The resolved structure may be described as being composed by aggregates of Ca(1)O9 and Ca(2)O5XO polyhedrons where X represents F, O, (OH) and Cl, as described by [6] or [34]. The cations Ca(1) are coordinated to nine oxygen anions belonging to six distinct tetrahedrons. Each polyhedron is linked to four PO4 tetrahedrons via corners and two other tetrahedrons via edges. The Ca(1)O9 polyhedrons (in reality tricapped-trigonal prisms according to [35]) share (001) faces to form chains parallel to a screw axis 63, parallel to the c-axis. The Ca(2) cations are inserted into fivefold sites that constitute the walls of tunnels built within mirror planes centered around the [001] zone axes and containing the halogen anions. In fact, each polyhedron Ca(2)O5XO is linked to three PO4 tetrahedrons via corners and adjacent Ca(1)O9 and Ca(2)O5XO polyhedrons are linked through oxygen atoms shared with PO4 tetrahedrons. The structure refined is better depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Projection of the structure of fluorapatite (sample 908) along (001), with (top) and without (bottom) structural polyhedrons. (Top) The magenta tetrahedrons represent PO4, and the gray blue polyhedrons represent Ca(1)O9 and Ca(2)O5FO polyhedrons. (Bottom) The red balls represent O2− anions, the small blue balls represent F- anions, the magenta balls represent P4+ cations and the large blue balls represent Ca2+ cations.

As shown by [4,6,35,36], apatite-group minerals are quite flexible regarding the presence of different anions in the c channels of the structure.

A model of “francolite-type” carbonate-for-phosphate substitution in apatite was built by incorporating one carbon atom at the center of a sloping face of the tetrahedral site and by substituting a fluoride ion for the opposite oxygen [37,38]. Apparently, the (CO3F)3−-for-(PO4)3− substitution in the samples from Valea Rea does not sufficiently disturb the structure, since the average P-O distance recorded in Table 4 (1.536 Å) is practically coincident with the average value observed in fluorapatite by [4]: P-O = 1.535 Å.

6. X-ray Powder Data

Cell parameters of two selected samples were successfully refined by least squares, based on a hexagonal P63/m cell, after indexing the patterns on the basis of PDF 83-0556, calculated using the structure considered by [6]. Sixty reflections in the 2θ range between 10 and 90°, for which unambiguous indexing was possible, were used for refinement. X-ray powder data are given as Supplementary Materials (Table S1). The obtained cell parameters are a = 9.385(7) Å and c = 6.891(9) Å for Sample 908 and a = 9.382(4) Å and c = 6.889(5) Å for Sample 909, respectively. In both cases, the values agree with those determined by single-crystal X-ray diffraction (Table 1). In all cases, the obtained values are larger as compared with those given for the stoichiometric fluorapatite by all the previous authors, e.g., a = 9.363(2) Å and c = 6.878(2) Å [39]; a = 9.367(1) Å and c = 6.884(1) Å [40]; a = 9.338(3) Å and c = 6.878(2) Å [6]; a = 9.371(2) Å and c = 6.885(2) Å [41]; a = 9.372(4) Å and c = 6.883(5) Å [42], but compare better with those given by some other authors for natural fluorapatite from skarns {e.g., a = 9.410(2) Å and c = 6.890(5) Å as given by [7], or hydrothermal fluorapatite from skarn-like veins {e.g., a = 9.392(6) Å and c = 6.888(4) Å as given by [43]}. Taking into account the chemical composition depicted below, it seems normal to imagine that the cationic substitutions in Ca sites, and particularly the REE presence, influenced the cell parameters (e.g., [44]).

The c/a ratio calculated for the two samples are, in both cases 1:0.734, very close to the values obtained for the stoichiometric fluorapatite based on the cell parameters given before (c/a = 0.734–0.736). As the data compiled by [1] confirm that c/a ratio increases with both Mn-for-Ca and Cl-for-F substitutions, it is shown that these substitutions are minor, if existent, in fluorapatite samples from Valea Rea.

7. Chemical Data

Electron-microprobe analyses of ten representative samples of fluorapatite from Valea Rea are given in Table 6. The individual analyses in the table represent averages of “N” point analyses on individual crystals from a same thin section. No chemical zoning or chemical inhomogeneity could be observed across the same crystal. As carbonate was not measured, formulas were normalized on the basis of 3(P + Si) per formula unit (pfu).

Table 6.

Representative electron-microprobe analyses of fluorapatite, Valea Rea *.

Subsequently, the O contents were re-adjusted for fulfilling the charge balance, resulting in the calculation of an oxyapatite component, whose structure must be identical which that of hydroxylapatite [45]. As the (CO3)2− groups occupies two different structural positions (see below) the fulfilling of the charge balance with a hypothetic “carbonate apatite” component seems inappropriate.

The chemical structural formula of fluorapatite from Valea Rea is consequently:

(Ca4.989Mn0.001Fe2+0.003Mg0.003Ce0.001La0.001)(P2.992Si0.008)(O11.894F1.202Cl0.001).

A few remarks must be drawn on the basis of the results in Table 6, as follows:

- (1)

- Fluorine contents in all samples (F = 4.00–4.80 wt.%, mean 4.42 wt.% F) exceed the ideal content of the stoichiometric apatite (F = 3.77 wt.%), which implies that part of the oxygen atoms that coordinate P in the PO4 tetrahedrons or in replacement tetrahedrons in the structure are replaced by F. The Cl-for-F substitution is minor. A wet chemical analysis of fluorine in the Valea Rea apatite, carried out using the pyrolytic method [46], confirmed the excess in fluorine of the analyzed sample, giving a fluorine content of 4.24(1) wt.% (mean of three different measurements on carefully selected powders). Taking into account the excess of fluorine, no hydroxyl was calculated for the compensation of the charge balance. On the contrary, the excess of fluorine imposes that this element exists not only in its normal positions in the c-axis channels in the structure, but also in structural positions normally occupied by other anions. This excess of fluorine firstly raises the problem of an appropriate substitution of F- for O2−. Even is challenging to imagine that fluorine enters in the O corners of the phosphate tetrahedrons, through an isovalent substitution of (CO3F)3−→ (PO4)3− [38,47] or even (PO3F) → (PO4)3− type [48], it is also probable that the excess fluorine enters the structural vacancies listed by [4,36] in the c-axis anion channels in the apatite structure.

- (2)

- All but three samples in Table 6 are slightly Ca-deficient, which implies minor (CO3)2− enters the structure. The most probable substitution is, in this case, (CO3F)3−-for-(PO4)3− [38,47].

- (3)

- The silica content is low (average 0.09 wt.% SiO2, equivalent of 0.008 Si a.p.f.u.), being characteristic for fluorapatite from hydrothermal systems [43]. Apatite from Valea Rea have lower Si than those in silicate magmas ([49] and references therein) and those in reaction skarns. By comparison, fluorapatite samples from reaction skarns have higher contents in silica (e.g., 0.5 wt.% SiO2 in skarns from Gatineau, Quebec: [8]). By contrast, no sulfate was detected, which implies that the substitution 2(PO4)3−→ (SiO4)4− + (SO6)2− substitution [50] is quite reduced.

- (4)

- The Ca2+ substitution by monovalent ions (K+, Na+) is lacking (both elements were sought but not detected over the error limit, and are ignored by Table 6); as these ions generally enters the larger Ca1 sites in the structure [4], the vacancies created in these sites by the replacements 2Na+→ Ca2+ + □ or 2K+→ Ca2+ + □ does not exist and does not create related vacancies in the F− sites [51].

- (5)

- The REE-for-Ca substitution is not important. The REE ions (i.e., La, Ce) are more compatible with the smaller Ca(2) sites in the structure [4,14,52] and involve replacements of 2REE3+ + □ → 3 Ca2+ type, or rather REE3+ + O2– = Ca2+ + F−, more probable in our case. The SiO44− group, which occupies the site of PO43−, could be, in its turn, a common charge compensator for REE3+ (e.g., [14] and referred works). As expected, the EMPA analysis revealed the enrichment in light REE (La and Ce) as compared with heavy REE (sought, but not detected), which characterizes fluorapatite from mineralized skarns analyzed by [14]. It seems that the affirmation that REE in fluorapatite is dominantly Ce [43] is confirmed in the case of the samples from Valea Rea.

- (6)

- The divalent substitutions by ions with smaller radii than Ca are restricted to Mg, Mn and Fe2+. Sr2+ and Ba2+ were sought, but their contents were in the limit of detection. The weak rates of substitution of Ca by Mg, Mn and Fe2+ does not cause large crystalline changes, because all these ions have radii smaller than Ca2+ in similar coordination [14]. The preference of Mn for the Ca(1) sites seems, however established ([35] and referred works) as well as the preference of Mg for Ca(2) sites [51]. The substitution ratio of Ca by divalent cations is generally weak in the Valea Rea fluorapatite, in good agreement with the general findings of [51]. The very low content of Mg substituting for Ca in the analyzed samples, which associate with forsterite, parallels the finding of [14] that fluorapatite associated with (magnesian) clinopyroxene in barren skarns has low Mg contents. Only 0.06% of the Ca positions are occupied by Mg, whereas another divalent cation, namely Fe2+, replaces Ca in the same proportion. The low contents in iron parallels the similar content of the associate silicates (i.e., forsterite) as well as the findings of [53] reported that the solubility limit of Fe in fluorapatite is relatively low (up to 15 mol% replacement of Ca2+ by Fe2+). The replacement of Ca by Mn2+ accounts for only 0.02% of the positions normally occupied by Ca, which is consistent with the chemical compositions of most of the natural fluorapatite samples reported by [2,36,49].

8. Physical Properties

The samples of fluorapatite from Valea Rea do not fluoresce either in short wave (λ = 254 nm), orin long wave (366 nm) ultraviolet radiation.

Macroscopically, the mineral has a blue-turquoise color. As expected, the mineral is uniaxial and optical negative. The indices of refraction, taken as mean of measurements on ten different grains, are: ω = 1.634(2) and ε = 1.631(1). These values are relatively close to those compiled for the stoichiometric and close to stoichiometry fluorapatite by [1]: ω = 1.6325–1.6357 and ε = 1.630–1.6328, which confirms the paucity or Cl-for-F as well as the lack of (OH)-for-F substitutions (both of them resulting in increasing refraction indices). The indices of refraction of fluorapatite from Valea Rea are lower than those measured for the more substituted fluorapatite from skarns {e.g., ω = 1.643(5) and ε = 1.639(5) for fluorapatite from Gondivalsa, India, according to [7]}, suggesting that fluorapatite from Valea Rea is of hydrothermal nature. The mean refraction index, calculated as = (2ω + ε)/3 [53] is 1.633.

The calculated densities of two representative samples were obtained on the basis of chemical data in Table 6 and of unit cell volumes calculated on the basis of XRD data, for Z = 2 formula units per cell: [2] and referred papers. The values obtained are Dx’ = 3.196 g/cm3 for Sample 908 and Dx’’ = 3.202 g/cm3 for Sample 909, respectively, resulting in a mean density Dx = 3.199 g/cm3. The mean measured density, taken as average of measurements on 10 different grains, is Dm = 3.201(3) g/cm3, which compares well with the calculated densities given before.

As derived from the mean refractive index given before and from the calculated densities, the physical refractive energy (KP) values are KP’ = 0.1981 for Sample 908 and KP” = 0.1977 for Sample 909, respectively. The chemical refractive energy (KC) values, based on the average EMP analyses of the two samples and on the constants given by [54], are KC’ = 0.1954 for Sample 908 and KC’’ = 0.1953 for Sample 909, respectively. The calculation of the Gladstone–Dale compatibility index (1 − Kp/Kc) yielded values of −0.0138 and −0.0123 respectively, both of them indicative of superior agreement between physical and chemical data [55]. The physical refractive energy calculated on the basis of the measured value of density is KP = 0.1978. The use of this value in the calculation does not influence substantially the compatibility index, which remains “superior” as ranked by [54].

9. Infrared and Raman Behavior

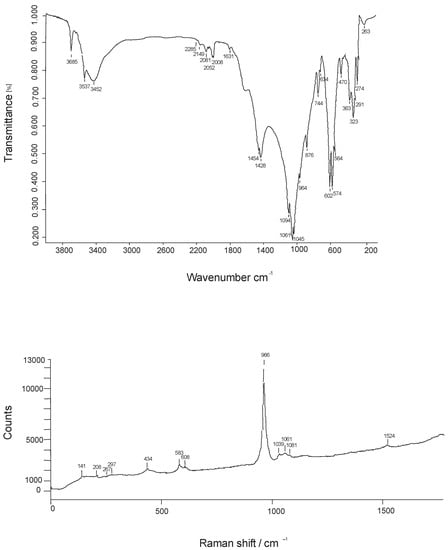

Representative infrared and Raman spectra obtained for fluorapatite from Valea Rea are given in Figure 6, whereas Table 7 gives wavenumbers, characters and intensities of the infrared absorption and Raman bands.

Figure 6.

FTIR spectrum of a representative sample of fluorapatite from Valea Rea (top) vs. a polarized Raman spectrum taken on (010) (bottom).

Table 7.

Positions and assignments of the FTIR and Raman bands recorded for s selected samples of fluorapatite from Valea Rea (1).

As considerable interest was devoted to the infrared and Raman study of fluorapatite, the works of [4,37,38,43,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65] were used to facilitate band assignments. A few remarks may be drawn based on the spectra in Figure 6, as follows:

- (1)

- The series of bands in the high-frequency region of the FTIR spectra (3000–4000 cm−1) expresses hydrogen-bounded OH groups. The band at 3695 cm−1 can be assumed to the symmetric F-OH stretching mode, whereas the band at 3570 cm−1 seems to materialize the antisymmetric OH-F-HO stretching mode [61]. Although both the mineral powder and the KBr were previously stored in a desiccator, both FTIR and Raman spectra clearly show absorption bands due to molecular water, whose main vibration is materialized by the broad hump centered at 3452 cm−1.

- (2)

- Bands centered at 1454 and 1428 cm−1, respectively, express the carbonate (antisymmetric) stretching. The corresponding bending modes occur at 876 and 744 cm−1, respectively. Both stretching and bending modes are split into two, which suggests that that carbonate groups occupy two different structural positions (e.g., [4,38]), both though 2 F− = (CO3)2− + □ and (PO4)3− = (CO3F)3−. Their frequencies are consistent with a dominant incorporation of the carbonate group into phosphate sites (1410–1430 and 1450–1460 cm−1 according to [59]. As the carbonate ion is particularly active in infrared [66], its strong signal in the infrared spectrum in Figure 6 (top) is normal. On the other side, the polarized Raman spectrum in Figure 6 (bottom), does not show any bands assignable to carbonate or water, indicating that much of these ions/molecules are located in the c structural channels, being inactive in a spectrum recorded almost in the (010) plane. This finding is coincident with the conclusion of [4], based on polarized infrared studies, that suggested that the orientation of the (CO3)2− ion lies in the position of the sloping face of the replaced (PO4)3− tetrahedron.

- (3)

- The PO43− ion has ideally a Td tetrahedral symmetry and nine vibrational modes corresponding to the representation Γvib = 2F2 + E + A [67]. Theoretically, the P-O stretching vibration ν1 (A1 symmetry) is non-degenerate, the ν2 out-of-plane O-P-O bending mode (E symmetry) is doubly degenerate, the ν3 antisymmetric stretching mode, involving also a P motion, is triply degenerate, as well as the in-plane ν4 O-P-O bending. Both ν3 and ν4 have F2 symmetry. For the ideal symmetry, all the modes are Raman active, while only ν3 and ν4 are infrared active. As can be seen in Table 7 the multiplicity of the infrared bands in our spectra is higher, implying that the replacement of part of PO43− by SiO44−, as well as the replacement of part of the oxygen corners of tetrahedrons with fluorine (the ionic radii being 1.24 Å for IVO2− vs. 1.17 Å for IVF−: [68]) distorts and lower the ideal Td symmetry of the phosphate tetrahedrons. In the spectra in Figure 6, the splitting of ν2 into two bands and of ν3 and ν4 phosphate modes into three bands agrees with the reduction of the symmetry of PO43− ion from Td to C6 [69]. A supplementary argument for the distortions of PO4 tetrahedrons from the ideal Td symmetry to C6 is offered by the broadening of the bands on the infrared spectrum [70]. In both Raman and infrared spectra, the ν1 P-O symmetric stretching vibration occurs at higher frequencies (963 and 965 cm−1, respectively) as compared to hydroxylapatite (960–963 cm−1 according to [4,56,57,63,65]). This shift toward higher frequencies of the P-O stretching band is a consequence of the shrinkage of Ca ions in the structure, due to the contraction of the unit cell induced by the smaller ionic radius of fluoride as compared to hydroxyl, confirming once again that the analyzed sample behaves as fluorapatite. As can be observed in Table 7, the Fermi resonance phenomenon is quite important in the case of phosphate group overtones and combination bands. Fluorine substitution in apatite leads to strong variations in the ν3 phosphate mode in the Raman spectrum [62]. The results of this study do not confirm the observations by [62] that the number of Raman bands in the 900–1100 cm−1 region decreases from seven (in hydroxyl- apatite) to five (in fluorapatite) with the incorporation of fluorine instead hydroxyl into apatite: only four bands were observed in our spectra, in agreement with the F overcompensation of the analyzed sample.

- (4)

- Small shoulders at ~915 cm−1 and ~520 cm−1 on the infrared spectra are due to the presence in the analyzed sample of SiO4 tetrahedrons [50]. No shoulders or supplementary bands of the high-frequency side of the bands which materializes the P-O symmetric stretching and in-plane ν4 O-P-O bending occur, implying the absence of the SO42− tetrahedrons (e.g., [50,65]).

10. Genetic Considerations

The crystallization of fluorapatite from Valea Rea is an expression of the hydrothermal activity associated with the intrusion of the Budureasa pluton, paralleling the fluorine metasomatism. The presence of fluorite on cooling cracks of the outer zone of Budureasa granodiorite is noteworthy and represents a solid argument for the F-rich character of the late hydrothermal fluids expelled by the intrusive body. In fact, fluorine is a ubiquitous constituent of this kind of fluid (e.g., [5] and referred works). It seems reasonable to consider that the source for fluorine is the magmatic body itself, as F-bearing minerals such as fluorapatite were recognized in granodiorite (contents of up to 1.78 wt.% P2O5 were reported by [19]). Fluorapatite close to the end-member, with low contents of chlorine and hydroxyl, was mentioned in Canadian skarns and in barren systems (e.g., [49] and referred works). Chemical peculiarities regarding the composition of fluorapatite from Valea Rea, as well as textural relations, characterize, however, hydrothermal fluorapatite (see [43] for chemical differences). Fluorapatite from Budureasa is a hydrothermal product, crystallizing after the prograde phase of skarn formation, during a retrogressive phase induced by the expulsion of F-rich fluids from the intrusive body. In fact, fluorapatite, that clearly postdates texturally forsterite and phlogopite, crystallizes during a high-temperature hydrothermal phase, induced by the introduction into the system of F-rich fluids. The texture of the Valea Rea skarn, where aggregates of fluorapatite form veins and pods, suggests that the F-bearing fluids expelled by the intrusive body used as pathways for reaction front propagation not only the rock fissures but also the grain boundaries and transient porosity in a process similar to that obtained by hydrothermal experiment [71].

Taking into account the textural relations, it seems that there are good reasons to believe that equilibrium in the skarn system was often disturbed during the hydrothermal and alteration events, and, after a medium-temperature hydrothermal phase, which induced the crystallization of serpentines, a new (low) hydrothermal phase induced the crystallization of fluorapatite, fluorite and remobilized calcite.

11. Conclusions

The fluorine-overcompensated carbonate-bearing fluorapatite from the Valea Rea skarns was formed during a high-temperature retrograde stage of system evolution, when fluorine metasomatism affected the magnesian skarns. A formula of Ca10(PO4)6−x(CO3F)xF2 type could explain the excess of fluorine as compared with the fluorapatite end-member. The (CO3F)3−-for-(PO4)3− replacement is low to moderate (x < 1) since a Ca10(PO4)5(CO3F)F2-type formula corresponds to a concentration of 6.0 wt% of CO3 [38], and of 5.74 wt.% F. In fact, fluorapatite slightly overcompensated in F as compared to the stoichiometric composition was already mentioned [72] in a carbonate-bearing fluorapatite (i.e., 3.88 wt.% F). The F surplus could be explained by the charge-compensation mechanism (CO3F)3− = (PO4)3− [36] and seems to materialize, for fluorapatite from Valea Rea, a type-B tetrahedral substitution [51]. However, evidence for the presence of (CO3F)3− groups from infrared and Raman study is still ambiguous, as already observed [36].

The replacement of (PO4)3− tetrahedrons by (CO3F)3− ones does not induce major structural changes and was not detected by the structural refinement based on X-ray diffraction. The analysis of data from vibrational spectroscopy provided support for the high symmetry, in the P63/m space group, in spite of the reduction of the symmetry of PO43− ion from Td to C6.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/min12091083/s1, Table S1. X-ray powder data of selected samples of fluorapatite from Valea Rea.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ş.M., D.-G.D., C.S.G. and F.D.B.; formal analysis, Ş.M., C.S.G. and F.D.B.; funding acquisition, Ş.M., C.S.G. and F.D.B.; investigation, Ş.M., D.-G.D. and F.D.B.; methodology, Ş.M., D.-G.D. and F.D.B.; resources, Ş.M., D.-G.D. and C.S.G.; data curation, D.-G.D., C.S.G. and F.D.B.; writing—original draft preparation, Ş.M.; writing—review and editing, Ş.M.; visualization, Ş.M.; supervision, Ş.M.; project administration, Ş.M., C.S.G. and F.D.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was partly supported by a scientific cooperative research grant awarded by the Walloon and Romanian Governments (4 BM/2021). Other grants awarded to the first author by UEFISCDI in Romania (PN-III-P1-1.2-PCCDI-2017-0346 and PN-III-P1-1.1-MC-2018-3163) and by the Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitization (PN19-45-01-02/2019, PN19-45-02-02/2019 and PN19-45-02-03/2019) generously supported the final draft. C.S.G. gratefully acknowledges the receipt of a UEFISCDI grant (PN-III-P1-1.1-MC-2018-3199) which helped to obtain part of the FTIR data.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The assistance of Michel Fialin (Université Paris VI) in the electron-microprobe work, of Erna Călinescu (“Prospecţiuni” S.A., Bucharest) in wet-chemical analysis and of Adrian Iulian Pantia (Geological Institute of Romania, Bucharest) in the X-ray powder and Raman analyses are gratefully acknowledged. Fruitful discussions on the field with the late Jean Verkaeren, with Bernard Guy, Essaïd Bilal, Gheorghe Ilinca, Frédéric Hatert and Maxime Baijot were highly appreciated.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Palache, C.; Berman, H.; Frondel, C. The System of Mineralogy, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1963; pp. 1–1124. [Google Scholar]

- Deer, W.A.; Howie, R.A.; Zussman, J. An Introduction to the Rock-Forming Minerals; Longman: London, UK, 1975; Volume 5, pp. 1–371. [Google Scholar]

- Nriagu, J.O. Phosphate minerals. Their properties and general modes of occurrence. In Phosphate Minerals; Nriagu, J.O., Moore, P.H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984; Chapter 1; pp. 1–136. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, J.C. Structure and chemistry of the apatites and the other calcium orthophosphates. In Studies in Inorganic Chemistry, 18th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994; pp. 1–404. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C.; Sverjensky, D.A. Partitioning of F-Cl-OH between minerals and hydrothermal fluids. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1991, 55, 1837–1858. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, J.M.; Cameron, M.; Crowley, K.D. Structural variations in natural F, OH, and Cl apatites. Am. Mineral. 1989, 74, 870–876. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, A.T.; Raman, C.V.; Prakassa Rao, C.S. Fluor-apatites from calc-silicate skarn vein contacts, Gondivalsa, Orissa, India. Mineral. Mag. 1979, 43, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogarth, D.D. Chemical composition of fluorapatite and associated minerals from skarn near Gatineau, Quebec. Mineral. Mag. 1988, 52, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissling, A. Crystallographic study of diopside and apatite from Ocna de Fier. St. Cerc. Geol. Geofiz. Geogr. Geol. 1971, 16, 515–519. [Google Scholar]

- Barkoff, D.W.; Ashley, K.T.; Steele-MacInnis, M. Pressures of skarn mineralization at Casting Copper, Nevada, USA, based on apatite inclusions in garnet. Geology 2017, 45, 947–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adlakha, E.; Hanley, J.; Falck, H.; Boucher, B. The origin of mineralizing hydrothermal fluids recorded in apatite chemistry at the Cantung W–Cu skarn deposit, NWT, Canada. Eur. J. Mineral. 2018, 30, 1095–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy-Garand, A. Characterization of Apatite within the Mactung W (Cu,Au) Skarn Deposit, Northwest Territories: Implication for the Evolution of Skarn Fluids. Unpubl. Ph.D. Thesis, Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, NS, Canada, 2019; pp. 1–89. [Google Scholar]

- Vakhrushev, V.A. Mineralogy, Geochemistry, and Genetic Groups of Contact-Metasomatic Deposits in the Altay-Sayan Region; Nauka: Novosibirsk, Russia, 1965; pp. 1–292. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Mao, M.; Rukhlov, A.S.; Rowins, S.M.; Spence, J.; Coogan, L.A. Apatite trace element compositions: A robust new tool for mineral exploration. Econ. Geol. 2016, 111, 1187–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivarsson, F. Characterization of Fe-Rich Skarn and Fluorapatite-Bearing Magnetite Occurrences at the Zinkgruvan Zn-Pb-Ag and Cu Deposit, Bergslagen, Sweden. Unpubl. Master’s Thesis, Luleå University of Technology, Luleå, Sweden, 2019; pp. 1–92. [Google Scholar]

- Tiringa, D.; Ateşçi, B.; Çelik, Y.; Demirkan, G.; Dőnmez, C.; Türkel, A.; Ünlü, T. Geology and formation of Nevruztepe Fe-Cu skarn mineralization (Kayseri-Turkey). Bull. Min. Res. Exp. 2020, 161, 101–119. [Google Scholar]

- Cioflica, G.; Vlad, Ş. The correlation of the Laramian metallogenetic events belonging to the Carpatho-Balkan area. Rev. Roum. Géologie Géophysique Géographie Série Géographie 1973, 17, 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Săndulescu, M.; Kräutner, H.; Borcoş, M.; Năstăseanu, S.; Patrulius, D.; Ştefănescu, M.; Ghenea, C.; Lupu, M.; Savu, H.; Bercia, I.; et al. Geological Map of Romania, Scale 1:1,000,000; Institute of Geology and Geophysics: Bucharest, Romania, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Ionescu, C.; Har, N. Geochemical considerations upon the banatites from Budureasa-Pietroasa area (Apuseni Mountains, Romania). Studia Univ. Babeş-Bolyai, Geol. 2001, 46, 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berza, T.; Constantinescu, E.; Vlad, Ş.N. Upper Cretaceous magmatic series and associated mineralization in the Carpatho - Balkan Orogen. Resour. Geol. 1998, 48, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciobanu, C.L.; Cook, N.J.; Stein, H. Regional setting and geochronology of the Late Cretaceous Banatitic Magmatic and Metallogenetic Belt. Miner. Depos. 2002, 37, 541–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, A.; Stein, H.; Hannah, J.; Koželj, D.; Bogdanov, K.; Berza, T. Tectonic configuration of the Apuseni—Banat—Timok—Srednogorie belt, Balkans-Southern Carpathians, constrained by high precision Re-Os molybdenite ages. Miner. Depos. 2008, 43, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilinca, G. Upper cretaceous contact metamorphism and related mineralizations in Romania. Acta Min. Petr. Abstr. Ser. 2012, 7, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ştefan, A.; Roşu, E.; Andăr, A.; Robu, L.; Robu, N.; Bratosin, I.; Grabari, E.; Stoian, M.; Vîjdea, E. Petrological and geochemical features of Banatitic magmatites in Northern Apuseni Mountains. Rom. J. Petrol. 1992, 75, 97–115. [Google Scholar]

- Bleahu, M.; Soroiu, M.; Catilina, R. On the Cretaceous tectonic–magmatic evolution of the Apuseni Mountains as revealed by K–Ar dating. Rev. Roum. Phys. 1984, 29, 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Whitney, D.L.; Evans, B.W. Abbreviations for names of rock-forming minerals. Am. Mineral. 2010, 95, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouchou, J.L.; Pichoir, F. PAP φ (ρZ) procedure for improved quantitative microanalysis. In Microbeam Analysis; Armstrong, J.T., Ed.; San Francisco Press: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1985; pp. 104–106. [Google Scholar]

- Goldoff, B.; Webster, J.D.; Harlov, D.E. Characterization of fluor-chlorapatites by electron probe microanalysis with a focus on time-dependent intensity variation of halogens. Am. Mineral. 2012, 97, 1103–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleman, D.E.; Evans, H.T., Jr. Indexing and least-squares refinement of powder diffraction data. US Geol. Surv. Comput. Contrib. 1973, 20, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Benoit, P.H. Adaptation to microcomputer of the Appleman-Evans program for indexing and least-squares refinement of powder-diffraction data for unit-cell dimensions. Am. Mineral. 1987, 72, 1018–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Agilent Technologies. Xcalibur CCD System, CrysAlis Software System; Agilent Technologies: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Palatinus, L.; Chapuis, G. Superflip—A computer program for the solution of crystal structures by charge flipping in arbitrary dimensions. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2007, 40, 786–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petříček, V.; Dušek, M.; Palatinus, L. Crystallographic computing system Jana 2006: General features. Z. Kristallogr. 2014, 229, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderín, L.; Stott, M.J.; Rubio, A. Electronic and crystallographic structure of apatites. Phys. Rev. 2003, 67, 134106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.M.; Rankovan, J.F. Structurally robust, chemically diverse: Apatite and apatite supergroup minerals. Elements 2015, 11, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.M.; Fleet, M.E. Compositions of the apatite-group minerals: Substitution mechanisms and controlling factors. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2002, 48, 13–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleet, M.E.; Liu, X. Location of type B carbonate ion in type A–B carbonate apatite synthesized at high pressure. J. Solid State Chem. 2004, 177, 3174–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.; Balan, E.; Gervais, C.; Ségalen, L.; Fayon, F.; Roche, D.; Person, A.; Morin, G.; Guillamet, M.; Blanchard, M.; et al. A carbonate-fluoride defect model for carbonate-rich fluorapatite. Am. Mineral. 2013, 98, 1066–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudarsanan, K.; Mackie, P.E.; Young, R.A. Comparison of synthetic and mineral fluorapatite, Ca5(PO4)3F, in crystallographic detail. Mater. Res. Bull. 1972, 7, 1331–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, P.E.; Young, R.A. Fluorine-chlorine interaction in fluor-chlorapatite. J. Solid State Chem. 1974, 11, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet, F.; Allan, D.R.; Redfern, A.T.S.; Angel, R.J.; Miletich, R.; Reichmann, H.J.; Sergent, J.; Hanfland, M. Compressibility and thermal expansivity of synthetic apatites, Ca5(PO4)3X with X = OH, F and Cl. Eur. J. Mineral. 1999, 11, 1023–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Hwang, P.; Witkowska, H.E.; Liu, H.; Li, W. Preparation and identification of single Fap crystal. In: 15. Quantitatively and kinetically identifying binding motifs of amelogenin proteins to mineral crystals through biochemical and spectroscopic assays. Methods Enzymol. 2013, 532, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y. Some mineralogical characters of fluorapatite in different genetic types. Bull. Minéralogie 1981, 104, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.M.; Fleet, M.E.; Chen, N.; Weil, J.A.; Nilges, M.J. Site preference of Gd in synthetic fluorapatite by single-crystal W-band EPR and X-ray refinement of the structure: A comparative study. Can. Mineral. 2002, 40, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alberius-Henning, P.; Landa-Canovas, A.; Larsson, A.-K.; Lidin, S. Elucidation of the crystal structure of oxyapatite by high-resolution electron microscopy. Acta Cryst. 1999, 55, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, J.A. Rock and mineral analysis. In Chemical Analysis. A Series of Monographs on Analytical Chemistry and Its Applications; Elving, P.J., Kolthoff, I.M., Eds.; Interscience Publishers: London, UK, 1968; Volume 27, pp. 1–584. [Google Scholar]

- Regnier, P.; Lasaga, A.C.; Berner, R.A.; Han, O.H.; Zilm, K.W. Mechanism of CO32- substitution in carbonate-fluorapatite: Evidence from FTIR spectroscopy, 13C NMR, and quantum mechanical calculation. Am. Mineral. 1994, 79, 809–818. [Google Scholar]

- Bastos Neto, C.; Pereira, V.P.; Pires, A.C.; Barbanson, L.; Chauvet, A. Fluorine-rich xenotime from the world-class Madeira Nb-Ta-Sn deposit associated with the albite-enriched granite at Pitinga, Amazonia, Brazil. Can. Mineral. 2012, 50, 1453–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J.D.; Piccoli, P.M. Magmatic apatite: A powerful, yet deceptive, mineral. Elements 2015, 11, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumer, A.; Caruba, R.; Ganteaume, M. Carbonate-fluorapatite: Mise en évidence de la substitution 2PO43- → SiO44- + SO62- par spectrométrie infrarouge. Eur. J. Mineral. 1990, 2, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, N.; Bres, E. Structure and substitutions in fluorapatite. Eur. Cells Mater. 2001, 2, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleet, M.E.; Pan, Y. Site preference of rare earth elements in fluorapatite. Am. Mineral. 1995, 80, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khudolozhkin, V.O.; Urusov, V.S.; Kurash, V.V. Mössbauer study of the ordering of Fe2+ in the fluor-apatite structure. Geochem. Intl. 1974, 11, 748–750. [Google Scholar]

- Mandarino, J.A. The Gladstone-Dale relationship—Part I: Derivation of new constants. Can. Mineral. 1976, 14, 498–502. [Google Scholar]

- Mandarino, J.A. The Gladstone-Dale relationship. IV. The compatibility concept and its application. Can. Mineral. 1981, 19, 441–450. [Google Scholar]

- Baddiel, C.B.; Berry, E.E. Spectra structure correlations in hydroxy and fluorapatite. Spectrochim. Acta 1966, 22, 1407–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, V.M. Infrared spectra of hydroxyapatite and fluorapatite. Bull. Soc. Chim. Fr. 1968, 91, 1771–1773. [Google Scholar]

- Klee, W. The vibrational spectra of the phosphate ions in fluorapatite. Zeit. Kristallogr. 1970, 131, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeGeros, R.Z.; LeGeros, J.P.; Trautz, O.R.; Klein, E. Spectral properties of carbonate in carbonate-containing apatites. Dev. Appl. Spectrosc. 1970, 7, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, B.O. Infrared studies of apatites. I. Vibrational assignments for calcium, strontium and barium hydroxyapatites utilizing isotopic substitution. Inorg. Chem. 1973, 13, 194–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, F.; Knobel, R.M. Distribution of fluorine in hydroxyapatite studied by infrared spectroscopy. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1977, 11, 1136–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penel, G.; Leroy, G.; Rey, C.; Sombret, B.; Huvenne, J.P.; Bres, E. Infrared and Raman microspectrometry study of fluor–fluor-hydroxy and hydroxy–apatite powders. J. Mater. Sci.Mater. Med. 1997, 8, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonakos, A.; Liarokapisa, E.; Leventouri, T. Micro-Raman and FTIR studies of synthetic and natural apatites. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 3043–3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balan, E.; Delattre, S.; Roche, D.; Segalen, L.; Morin, G.; Guillaumet, M.; Blanchard, M.; Lazzeri, M.; Brouder, C.; Salje, E.K.H. Line-broadening effects in the powder infrared spectrum of apatite. Phys. Chem. Miner. 2010, 38, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Kou, G.; Etschmann, B.; Liu, D.; Brugger, J. Spectroscopic, Raman, EMPA, micro-XRF and micro-XANES analyses of sulphur concentration and oxidation state of natural apatite crystals. Crystals 2020, 10, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, K. Infrared and Raman Spectra of Inorganic and Coordination compounds. In Part A: Theory and Applications in Inorganic Chemistry, 5th ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 1–387. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, A.; Krebs, B. Normal coordinate treatment of XY4-type molecules and ions with Td symmetry. Part I. Force constants of a modified valence force field and of the Urey-Bradley force field. J. Molec. Spectrosc. 1967, 24, 180–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, R.D. Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Acta Crystallogr. 1976, 32, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitraş, D.G.; Marincea, Ş.; Bilal, E.; Hatert, F. Apatite-(CaOH) in the fossil bat guano deposit from the “dry” Cioclovina Cave, Şureanu Mountains, Romania. Can. Mineral. 2008, 46, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buvaneswari, G.; Varadaraju, U.V. Synthesis and characterization of new apatite-related phosphates. J. Solid State Chem. 2000, 149, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, L.; John, T.; King, H.E.; Geisler, T.; Putnis, A. The role of grain boundaries and transient porosity in rocks as fluid pathways for reaction front propagation. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2014, 386, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brophy, G.P.; Nash, J.T. Compositional, infrared, and X-ray analysis of fossil bone. J. Earth Planet. Mater. 1968, 53, 445–454. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).