Evaluation of Three Recombinant Antigens for the Detection of Anti-Coxiella Antibodies in Cattle

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Antigen Selection, Amplification, Ligation

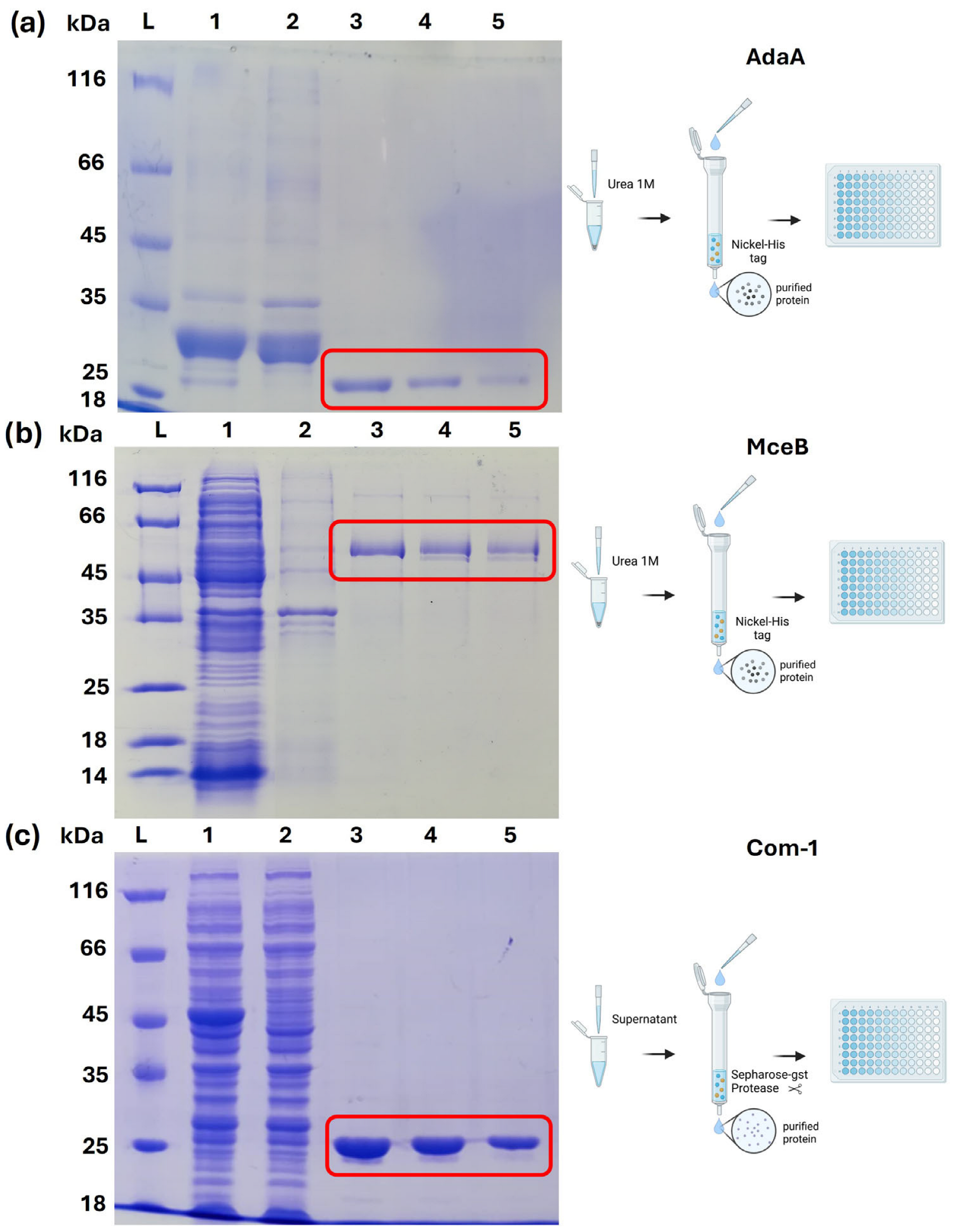

2.2. Expression and Purification

2.3. Recombinant ELISAs

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CFT | Complement fixation test |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| IFA | Immunofluorescence Assay |

| LAT | Latex agglutination test |

| GST | Glutathione S-Transferase |

| TMB | 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine |

| IPTG | Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside |

| WOAH | World Organisation for Animal Health |

References

- Angelakis, E.; Raoult, D. Q Fever. Vet. Microbiol. 2010, 140, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guatteo, R.; Seegers, H.; Taurel, A.F.; Joly, A.; Beaudeau, F. Prevalence of Coxiella burnetii Infection in Domestic Ruminants: A Critical Review. Vet. Microbiol. 2011, 149, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, B.U.; Knittler, M.R.; Andrack, J.; Berens, C.; Campe, A.; Christiansen, B.; Fasemore, A.M.; Fischer, S.F.; Ganter, M.; Körner, S.; et al. Interdisciplinary Studies on Coxiella burnetii: From Molecular to Cellular, to Host, to One Health Research. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2023, 313, 151590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisbert, P.; Garcia-Ispierto, I.; Quintela, L.A.; Guatteo, R. Coxiella burnetii and Reproductive Disorders in Cattle: A Systematic Review. Animals 2024, 14, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, G.; Longobardi, C.; Pagnini, U.; Iovane, G.; D’Ausilio, F.; Montagnaro, S. Evaluation of the Phase-Specific Antibody Response in Water Buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) after Two Doses of an Inactivated Phase I Coxiella burnetii Vaccine. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2024, 277, 110840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.M.; Zadoks, R.N.; Kim, P.S.; Bosward, K.L.; Brookes, V.J. A Scoping Review of Coxiella burnetii Transmission Models in Ruminants. Prev. Vet. Med. 2026, 246, 106715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pexara, A.; Solomakos, N.; Govaris, A. Q Fever and Seroprevalence of Coxiella burnetii in Domestic Ruminants. Vet. Ital. 2018, 54, 265–279. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara, G.; Pagnini, U.; Improda, E.; Iovane, G.; Montagnaro, S. Pigs in Southern Italy Are Exposed to Three Ruminant Pathogens: An Analysis of Seroprevalence and Risk Factors Analysis Study. BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, G.; Flores-Ramirez, G.; Palkovicova, K.; Ferrucci, F.; Pagnini, U.; Iovane, G.; Montagnaro, S. Serological and Molecular Survey of Q Fever in the Dog Population of the Campania Region, Southern Italy. Acta Trop. 2024, 257, 107299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epelboin, L.; De Souza Ribeiro Mioni, M.; Couesnon, A.; Saout, M.; Guilloton, E.; Omar, S.; De Santi, V.P.; Davoust, B.; Marié, J.L.; Lavergne, A.; et al. Coxiella burnetii Infection in Livestock, Pets, Wildlife, and Ticks in Latin America and the Caribbean: A Comprehensive Review of the Literature. Curr. Trop. Med. Rep. 2023, 10, 94–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, Q.; Jamil, T.; Saqib, M.; Iqbal, M.; Neubauer, H. Q Fever—A Neglected Zoonosis. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldin, C.; Mélenotte, C.; Mediannikov, O.; Ghigo, E.; Million, M.; Edouard, S.; Mege, J.L.; Maurin, M.; Raoult, D. From Q Fever to Coxiella burnetii Infection: A Paradigm Change. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 30, 115–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo-Perona, R.; Contreras, A.; Gomis, J.; Quereda, J.J.; García-Galán, A.; Sánchez, A.; Gómez-Martín, Á. Controlling Coxiella burnetii in Naturally Infected Sheep, Goats and Cows, and Public Health Implications: A Scoping Review. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1321553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisbert, P.; Hurtado, A.; Guatteo, R. Efficacy and Safety of an Inactivated Phase I Coxiella burnetii Vaccine to Control Q Fever in Ruminants: A Systematic Review. Animals 2024, 14, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WOAH. Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals, 13th edition. World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH). 2024. Available online: https://www.woah.org/fileadmin/Home/eng/Health_standards/tahm/A_summry.htm (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- García-Pérez, A.L.; Zendoia, I.I.; Ferrer, D.; Barandika, J.F.; Ramos, C.; Vera, R.; Martí, T.; Pujol, A.; Cevidanes, A.; Hurtado, A. Combination of Serology and PCR Analysis of Environmental Samples to Assess Coxiella burnetii Infection Status in Small Ruminant Farms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2025, 91, e00931-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.E.; Hubbard, K.R.A.; Johnson, A.J.; Messick, J.B.; Weng, H.Y.; Pogranichniy, R.M. A Cross Sectional Study Evaluating the Prevalence of Coxiella burnetii, Potential Risk Factors for Infection, and Agreement between Diagnostic Methods in Goats in Indiana. Prev. Vet. Med. 2016, 126, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymańska-Czerwińska, M.; Niemczuk, K.; Jodełko, A. Evaluation of QPCR and Phase I and II Antibodies for Detection of Coxiella burnetii Infection in Cattle. Res. Vet. Sci. 2016, 108, 68–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walraph, J.; Zoche-Golob, V.; Weber, J.; Freick, M. Decline of Antibody Response in Indirect ELISA Tests during the Periparturient Period Caused Diagnostic Gaps in Coxiella burnetii and BVDV Serology in Pluriparous Cows within a Holstein Dairy Herd. Res. Vet. Sci. 2018, 118, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horigan, M.W.; Bell, M.M.; Pollard, T.R.; Sayers, A.R.; Pritchard, G.C. Q Fever Diagnosis in Domestic Ruminants: Comparison between Complement Fixation and Commercial Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2011, 23, 924–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, C.; Muleme, M.; Tan, T.; Bosward, K.; Gibson, J.; Alawneh, J.; McGowan, M.; Barnes, T.S.; Stenos, J.; Perkins, N.; et al. Validation of an Indirect Immunofluorescence Assay (IFA)for the Detection of IgG Antibodies against Coxiella burnetii in Bovine Serum. Prev. Vet. Med. 2019, 169, 104698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahu, R.; Rawool, D.B.; Vinod, V.K.; Malik, S.V.S.; Barbuddhe, S.B. Current Approaches for the Detection of Coxiella burnetii Infection in Humans and Animals. J. Microbiol. Methods 2020, 179, 106087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, M.P.; Ostlund, E.N.; Schmitt, B.J. Comparison of Q Fever Serology Methods in Cattle, Goats, and Sheep. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2012, 24, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, G.; Colitti, B.; Pagnini, U.; Iovane, G.; Rosati, S.; Montagnaro, S. Characterization of Recombinant Ybgf Protein for the Detection of Coxiella Antibodies in Ruminants. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2022, 34, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, S.; Toft, N.; Agerholm, J.S.; Christoffersen, A.B.; Agger, J.F. Bayesian Estimation of Sensitivity and Specificity of Coxiella burnetii Antibody ELISA Tests in Bovine Blood and Milk. Prev. Vet. Med. 2013, 109, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogerwerf, L.; Koop, G.; Klinkenberg, D.; Roest, H.I.J.; Vellema, P.; Nielen, M. Test and Cull of High Risk Coxiella burnetii Infected Pregnant Dairy Goats Is Not Feasible Due to Poor Test Performance. Vet. J. 2014, 200, 343–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, G.; Colitti, B.; Flores-Ramirez, G.; Pagnini, U.; Iovane, G.; Rosati, S.; Montagnaro, S. Detection of Coxiella Antibodies in Ruminants Using a SucB Recombinant Antigen. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2023, 35, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, I.; Rousset, E.; Dufour, P.; Sidi-Boumedine, K.; Cupo, A.; Thiéry, R.; Duquesne, V. Evaluation of the Recombinant Heat Shock Protein B (HspB) of Coxiella burnetii as a Potential Antigen for Immunodiagnostic of Q Fever in Goats. Vet. Microbiol. 2009, 134, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, H.K.; Kersh, G.J. Analysis of Recombinant Proteins for Q Fever Diagnostics. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, G.; Chen, S.; Plain, K.; Marsh, I.; Westman, M.E.; Stenos, J.; Graves, S.R.; Rehm, B.H.A. Diphtheria Toxoid Particles as Q Fever Vaccine. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2309256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, E.; Fitzgerald, S.F.; Williams-MacDonald, S.E.; Mitchell, M.; Golde, W.T.; Longbottom, D.; Nisbet, A.J.; Dinkla, A.; Sullivan, E.; Pinapati, R.S.; et al. Genome-Wide Epitope Mapping across Multiple Host Species Reveals Significant Diversity in Antibody Responses to Coxiella burnetii Vaccination and Infection. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1257722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Wang, X.; Wen, B.; Graves, S.; Stenos, J. Potential Serodiagnostic Markers for Q Fever Identified in Coxiella burnetii by Immunoproteomic and Protein Microarray Approaches. BMC Microbiol. 2012, 12, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerlach, C.; Škultéty, L.; Henning, K.; Neubauer, H.; Mertens, K. Coxiella burnetii Immunogenic Proteins as a Basis for New Q Fever Diagnostic and Vaccine Development. Acta Virol. 2017, 61, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beare, P.A.; Chen, C.; Bouman, T.; Pablo, J.; Unal, B.; Cockrell, D.C.; Brown, W.C.; Barbian, K.D.; Porcella, S.F.; Samuel, J.E.; et al. Candidate Antigens for Q Fever Serodiagnosis Revealed by Immunoscreening of a Coxiella burnetii Protein Microarray. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2008, 15, 1771–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Xiong, X.; Qi, Y.; Gong, W.; Duan, C.; Yang, X.; Wen, B. Serological Characterization of Surface-Exposed Proteins of Coxiella burnetii. Microbiology 2014, 160, 2718–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigil, A.; Ortega, R.; Nakajima-Sasaki, R.; Pablo, J.; Molina, D.M.; Chao, C.C.; Chen, H.W.; Ching, W.M.; Felgner, P.L. Genome-Wide Profiling of Humoral Immune Response to Coxiella burnetii Infection by Protein Microarray. Proteomics 2010, 10, 2259–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palkovicová, K.; Flores-Ramírez, G.; Quevedo-Diaz, M.; Csicsay, F.; Skultety, L. Innovative Antigens for More Accurate Diagnosis of Q Fever. J. Microbiol. Methods 2025, 232–234, 107106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stellfeld, M.; Gerlach, C.; Richter, I.G.; Miethe, P.; Fahlbusch, D.; Polley, B.; Sting, R.; Pfeffer, M.; Neubauer, H.; Mertens-Scholz, K. Evaluation of the Diagnostic Potential of Recombinant Coxiella burnetii Com1 in an Elisa for the Diagnosis of q Fever in Sheep, Goats and Cattle. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, J.P.; Malik, S.V.S.; Dhaka, P.; Kumar, M.; Sirsant, B.; Gourkhede, D.; Barbuddhe, S.B.; Rawool, D.B. Comparison of Two New In-House Latex Agglutination Tests (LATs), Based on the DnaK and Com1 Synthetic Peptides of Coxiella burnetii, with a Commercial Indirect-ELISA, for Sero-Screening of Coxiellosis in Bovines. J. Microbiol. Methods 2020, 170, 105859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Kiss, K.; Seshadri, R.; Hendrix, L.R.; Samuel, J.E. Identification and Cloning of Immunodominant Antigens of Coxiella burnetii. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, G.; Colitti, B.; Gabriela, F.R.; Rosati, S.; Iovane, G.; Pagnini, U.; Montagnaro, S. Efficiency of Recombinant Ybgf in a Double Antigen-ELISA for the Detection of Coxiella Antibodies in Ruminants. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2024, 25, 100366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, B.U.; Schwecht, K.M.; Jahnke, R.; Matthiesen, S.; Ganter, M.; Knittler, M.R. Humoral and Cellular Immune Responses in Sheep Following Administration of Different Doses of an Inactivated Phase I Vaccine against Coxiella burnetii. Vaccine 2023, 41, 4798–4807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchese, L.; Capello, K.; Barberio, A.; Zuliani, F.; Stegeman, A.; Ceglie, L.; Guerrini, E.; Marangon, S.; Natale, A. IFAT and ELISA Phase I/Phase II as Tools for the Identification of Q Fever Chronic Milk Shedders in Cattle. Vet. Microbiol. 2015, 179, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lurier, T.; Rousset, E.; Gasqui, P.; Sala, C.; Claustre, C.; Abrial, D.; Dufour, P.; de Crémoux, R.; Gache, K.; Delignette-Muller, M.L.; et al. Evaluation Using Latent Class Models of the Diagnostic Performances of Three ELISA Tests Commercialized for the Serological Diagnosis of Coxiella burnetii Infection in Domestic Ruminants. Vet. Res. 2021, 52, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivière, L.; Rousset, E.; Jourdain, E.; Delignette-Muller, M.L.; Lurier, T. Harmonisation of the Diagnostic Performances of Serological ELISA Tests for C. Burnetii in Ruminants in the Absence of a Gold Standard: Optimal Cut-Offs and Performances Reassessment. Prev. Vet. Med. 2025, 239, 106509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deringer, J.R.; Chen, C.; Samuel, J.E.; Brown, W.C. Immunoreactive Coxiella burnetii Nine Mile Proteins Separated by 2D Electrophoresis and Identified by Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Microbiology 2011, 157, 526–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranakis, I.; Mathioudaki, E.; Kokkini, S.; Psaroulaki, A. Com1 as a Promising Protein for the Differential Diagnosis of the Two Forms of q Fever. Pathogens 2019, 8, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | IDEXX+ | IDEXX− | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| MceB+ | 41 | 37 | |

| MceB− | 14 | 23 | |

| Total | 55 | 60 | 115 |

| AdaA+ | 17 | 15 | |

| AdaA− | 38 | 45 | |

| Total | 55 | 60 | 115 |

| Com-1+ | 80 | 28 | |

| Com1− | 40 | 253 | |

| Total | 120 | 281 | 401 |

| Species | Agreement (95% CI) | Cohen κ (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| MceB | 0. 56 (46.1–64.9) | 0.13 (0–0.29) |

| AdaA | 0.54 (44.4–63.2) | 0.06 (0–0.22) |

| Com-1 | 0.83 (79–86.6) | 0.58 (0.49–0.67) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Colitti, B.; Longobardi, C.; Flores-Ramirez, G.; Nogarol, C.; Skultety, L.; Ferrara, G. Evaluation of Three Recombinant Antigens for the Detection of Anti-Coxiella Antibodies in Cattle. Antibodies 2025, 14, 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/antib14040107

Colitti B, Longobardi C, Flores-Ramirez G, Nogarol C, Skultety L, Ferrara G. Evaluation of Three Recombinant Antigens for the Detection of Anti-Coxiella Antibodies in Cattle. Antibodies. 2025; 14(4):107. https://doi.org/10.3390/antib14040107

Chicago/Turabian StyleColitti, Barbara, Consiglia Longobardi, Gabriela Flores-Ramirez, Chiara Nogarol, Ludovit Skultety, and Gianmarco Ferrara. 2025. "Evaluation of Three Recombinant Antigens for the Detection of Anti-Coxiella Antibodies in Cattle" Antibodies 14, no. 4: 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/antib14040107

APA StyleColitti, B., Longobardi, C., Flores-Ramirez, G., Nogarol, C., Skultety, L., & Ferrara, G. (2025). Evaluation of Three Recombinant Antigens for the Detection of Anti-Coxiella Antibodies in Cattle. Antibodies, 14(4), 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/antib14040107