Implications of Customary Land Rights Inequalities for Food Security: A Study of Smallholder Farmers in Northwest Ghana

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Land Rights and Tenure Security

1.2. Customary Land Rights Inequalities and Food Production

1.3. Food Security and Its Dimensions

2. Methodology

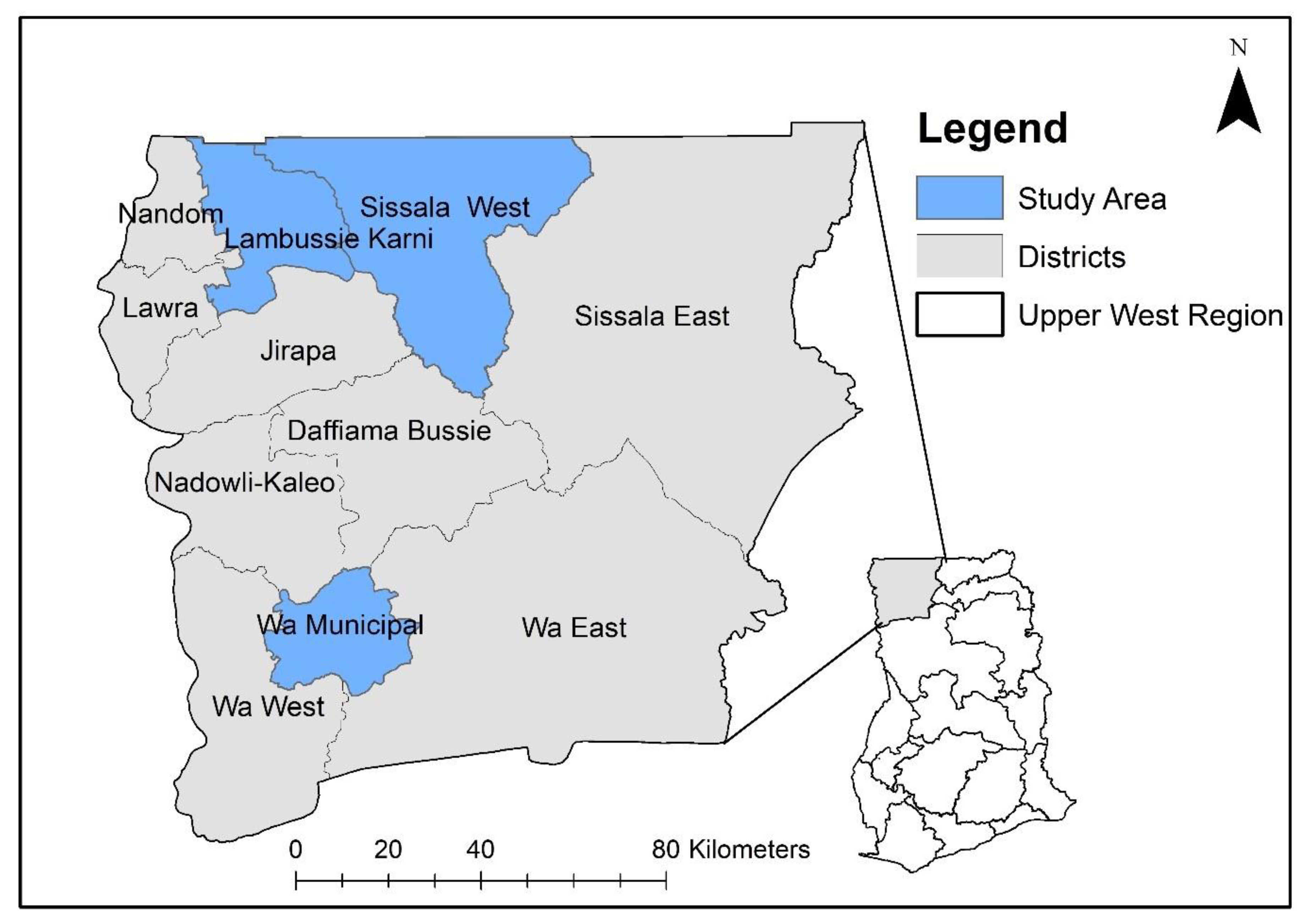

2.1. Study Area

- (1)

- Allodial title: the highest interest in land, communally owned by members of the landowning group.

- (2)

- Customary freehold or usufructuary interest: family land use rights held perpetually by members holding the allodial title.

- (3)

- Common law freehold right: acquired through express grant from the allodial owner or customary freeholder, either through sale, gift or other arrangements, and usually held by non-members.

- (4)

- Leasehold, sub-leases and customary tenancy rights.

2.2. Selection of Participants for Focus Group Discussions

2.3. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Nature of Land Rights Inequalities

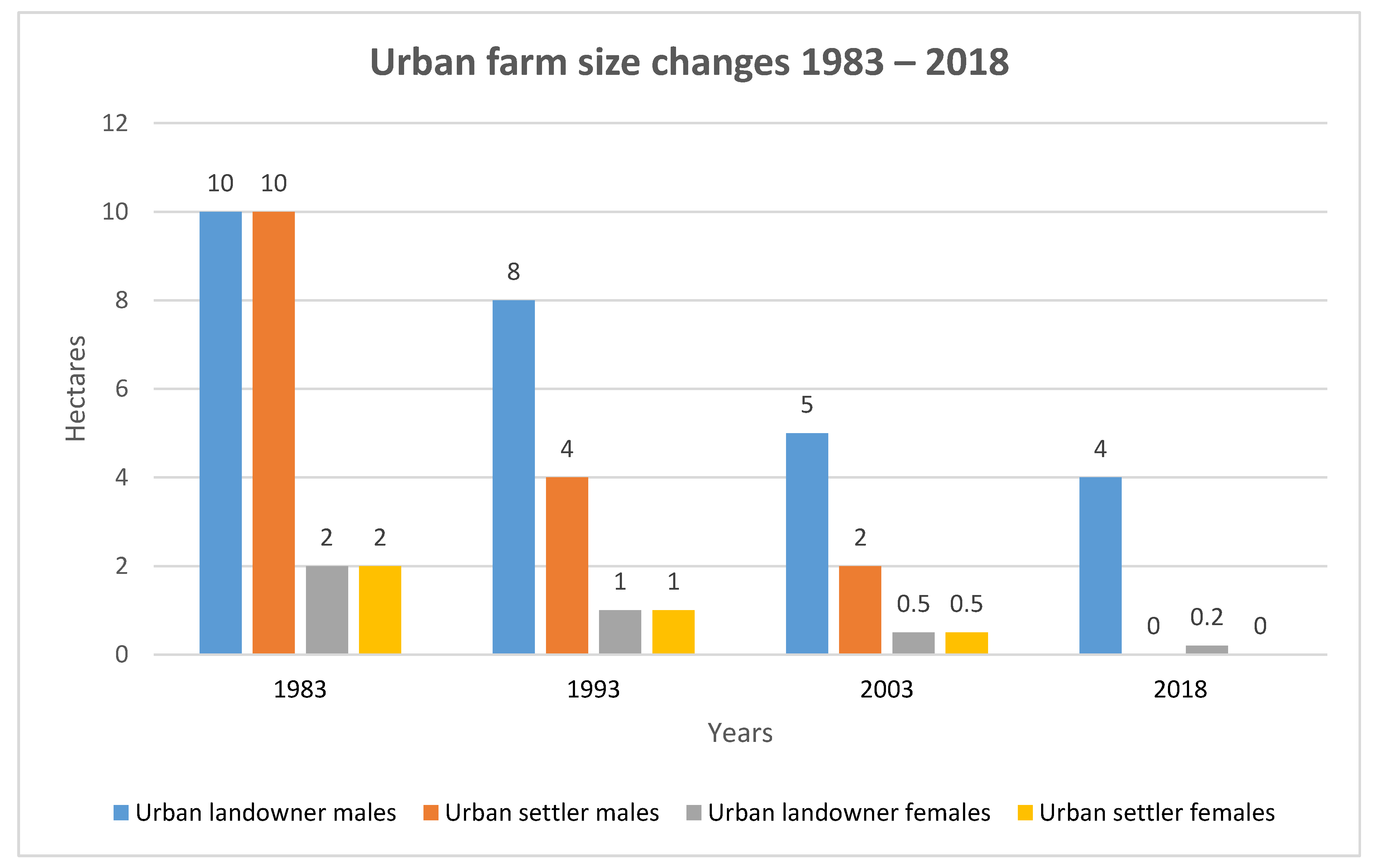

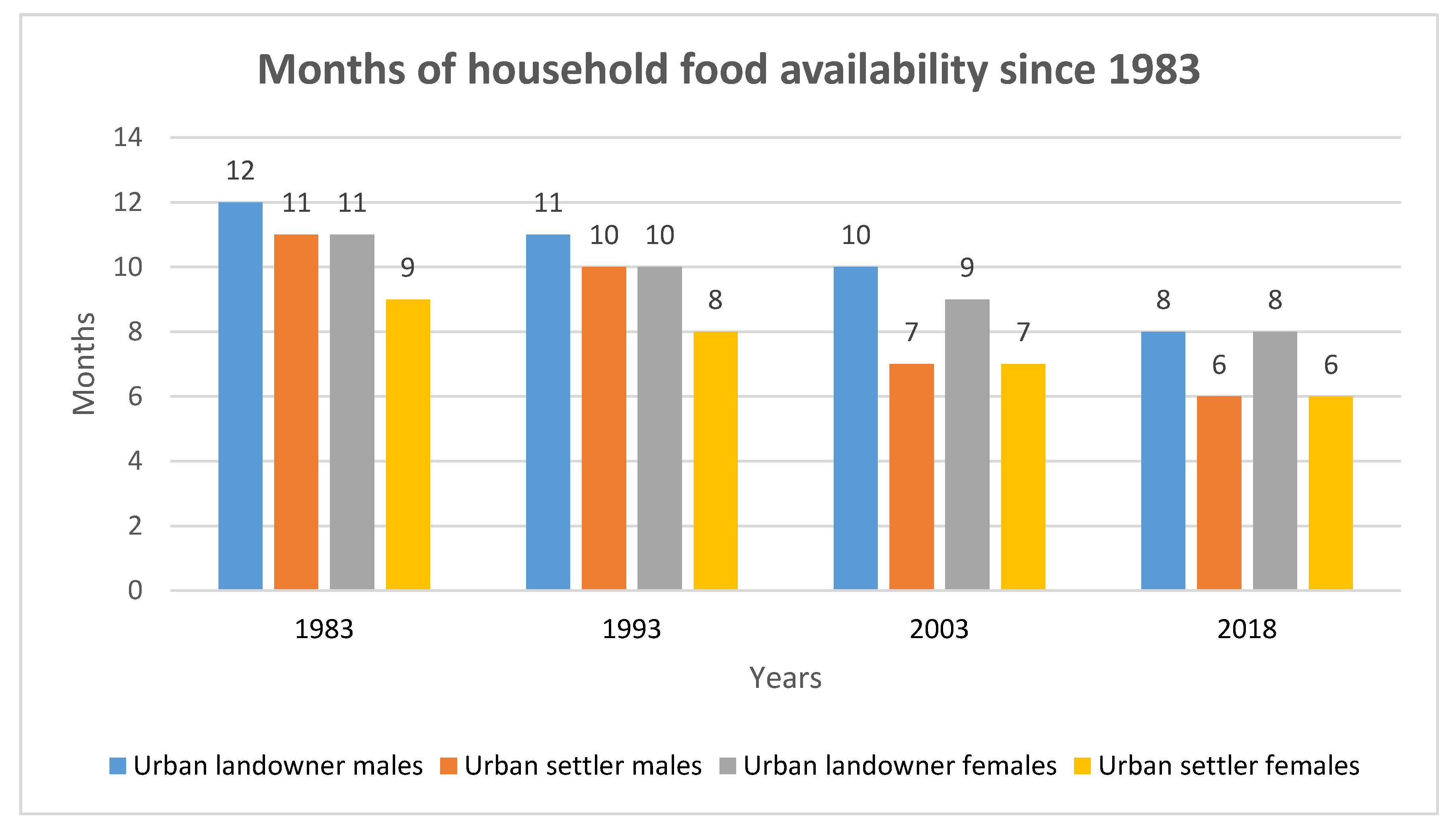

3.2. Implications for Farming, Food Availability and Food Security

3.3. Other Implications

“How can you purport to be establishing a university for people and you are indirectly sacking us and not making any arrangements to resettle or even compensate us? Worst of it, you will not even allow us to squat until actual construction commences. Just because we have no one to speak for us, that is why our age-old land rights are being trampled on and making life for us miserable with nearly no hope for the future of our children. What manner of development is this? Therefore, you see why peaceful co-existence is eluding all of us (landowners and settlers). This also negatively affects our freedom to work on the little farmlands since we fear attacks from even developers thereby affecting both farming activities and food security.”

“We currently survive by negotiating with land developers who purchased our farms from our landlords to ‘squat’ and farm on their plots until the lands are needed for development. However, when this fails, we encroach on people’s plots knowing that eviction is imminent. How can we possibly be assured of food security under these conditions?”

“The land is just not available for us now, so on what can we produce our own food if not on it? Given the current landlessness among us—settlers, our youth and middle-aged people have been pushed out of the community and out of frustration may do “anything” [referring to unlawful means] to provide for their wives and children. Now you talk about buying food from the market, even though there is some food in the market, but our main source of income is the same farming that we can no longer do effectively. So, it is difficult to meet our food needs if our land rights and tenure issues remain unresolved.”

4. Discussions

4.1. Nature of Land Rights Inequalities

4.2. Implications for Food Production, Food Availability and Food Security

4.3. Indirect Implications

4.4. Conclusion and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maxwell, D.; Wiebe, K. Land Tenure and Food Security: Exploring dynamic linkages. Dev. Chang. 1999, 30, 825–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Yan, Z.; Xu, D. Agricultural Machinery Adoption: Empirical Analysis. Land 2020, 9, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wegerif, M.C.; Guerena, A. Land Inequality Trends and Drivers. Land 2020, 9, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lipton, M.; Saghai, Y. Food security, farmland access ethics, and land reform. Glob. Food Sec. 2017, 12, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, J.F. The impact of climate change on smallholder and subsistence agriculture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 19680–19685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Azadi, H.; Vanhaute, E. Mutual Effects of Land Distribution and Economic Development: Evidence from Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Land 2019, 8, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zant, W. What makes Smallholders move out of Subsistence Farming: Is Access to Cash Crop Markets going to do the Trick? Ipd. Gu. Se 2005, 95, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bruil, J. Towards stronger family farms. Recommendations from the International Year of Family Farming. Farming Matters 2014, 30, 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Myers Gregory, F.M. Land Tenure and Property Rights Framework; USAID: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Volume 1.

- Obeng-Odoom, F. Land reforms in Africa: Theory, practice, and outcome. Habitat Int. 2012, 36, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauveau, J.-P.; Cissé, S.; Colin, J.-P.; Cotula, L.; Delville, P.L.; Neves, B.; Quan, J.T. Changes in “Customary” Land Tenure Systems in Africa Edited by Lorenzo Cotula; Cotula, L., Ed.; IIED: London, UK; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2007; ISBN 9781843696575.

- Kidido, J.K.; Bugri, J.T.; Kasanga, R.K. Dynamics of youth access to agricultural land under the customary tenure regime in the Techiman traditional area of Ghana. Land Use Policy 2017, 60, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugri, J.T. The dynamics of tenure security, agricultural production and environmental degradation in Africa: Evidence from stakeholders in north-east Ghana. Land Use Policy 2008, 25, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akrofi, E.O.; Whittal, J. Traditional Governance and Customary Peri-Urban Land Delivery: A Case Study of Asokore-Mampong in Ghana. In Proceedings of the AfricanGeo Conference, Cape Town, South Africa, 31 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Naab, F.Z.; Dinye, R.D.; Kasanga, R.K. Urbanisation and its impact on agricultural lands in growing cities in developing countries: A case study of Tamale in Ghana. Mod. Soc. Sci. J. 2013, 2, 256–287. [Google Scholar]

- Abubakari, Z.; Richter, C.; Zevenbergen, J. Exploring the “implementation gap” in land registration: How it happens that Ghana’s official registry contains mainly leaseholds. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carte, L.; Schmook, B.; Radel, C.; Johnson, R. The slow displacement of smallholder farming families: Land, hunger, and labor migration in Nicaragua and Guatemala. Land 2019, 8, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lawry, S.; Samii, C.; Hall, R.; Leopold, A.; Hornby, D.; Mtero, F. The impact of land property rights interventions on investment and agricultural productivity in developing countries. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2014, 10, 1–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruerd, R. Improving Food Security. A Systematic Review of the Impact of Interventions in Agricultural Production, Value Chains, Market Regulation, and Land Security; Ministry of Foreign Affairs: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2011.

- Conway, G. On Being a Smallholder. In Proceedings of the Conference on New Directions for Smallholder Agriculture, Rome, Italy, 24–25 January 2011; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gazdar, H.; Khan, A.; Khan, T. Land Tenure, Rural Livelihoods and Institutional Innovation; Mimeo: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cotula, L.; Toulmin, C.; Quan, J. Better Land Access for the Rural Poor and Challenges Ahead; IIED: London, UK, 2006; ISBN 1843696320. [Google Scholar]

- Yaro, J.A. Customary tenure systems under siege: Contemporary access to land in Northern Ghana. GeoJournal 2010, 75, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkegbe, P.K.; Abu, B.M.; Issahaku, H. Food security in the Savannah Accelerated Development Authority Zone of Ghana: An ordered probit with household hunger scale approach. Agric. Food Secur. 2017, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asiama, K.; Bennett, R.; Zevenbergen, J. Participatory Land Administration on Customary Lands: A Practical VGI Experiment in Nanton, Ghana. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2017, 6, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lengoiboni, M.; Richter, C.; Zevenbergen, J. Cross-cutting challenges to innovation in land tenure documentation. Land Use Policy 2019, 85, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Electoral Commission. Land Tenure Systems and their Impacts on Food Security and Sustainable Development in Africa; AEC: Canberra, Australia, 2004.

- Ballard, T.J.; Kepple, A.W.; Cafiero, C. The Food Insecurity Experience Scale: Development of a Global Standard for Monitoring Hunger Worldwide; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013.

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Land Tenure and Rural Development; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2002; ISBN 92-5-104846-0.

- FAO; IFAD; WFP. The State of Food Insecurity in the World: Meeting the 2015 International Hunger Targets: Taking Stock of Uneven Progress; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015.

- Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture (BMLE). Understanding Global Food Security and Nutrition Facts and Backgrounds; Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture (BMLE): Bonn, Germany, 2015; Volume 29.

- Andersen, K.E. Communal Tenure and the Governance of Common Property Resources in Asia—Lessons From Experiences in Selected Countries. L. Tenure 2011, 1–3, 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, H. Farmers’ Land Tenure Security in Vietnam and China. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cotula, L.; Mathieu, P. Legal Empowerment in Practice: Using Legal Tools to Secure Land Rights in Africa; IIED: London, UK, 2008; ISBN 9781843697039. [Google Scholar]

- Bugri, J.T. Understanding Changing Land Access and Use by the Rural Poor in Ghana; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 9781784314507. [Google Scholar]

- Djokoto, G.; Opoku, K. Land tenure in Ghana: Making a case for incorporation of customary law in land administration and areas of intervention by the growing forest partnership. Int. Union Conserv. Nat. Grow. For. Partnerships 2010, 9, 10–34. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Ghana. Population and Housing Census Report; Ghana Statistical Service: Accra, Ghana, 2012.

- Kothari, C.; Kumar, R.; Uusitalo, O. Research Methodology; New Age International: New Delhi, India, 2014; ISBN 9788122424881. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, B.; Ockleford, E.; Windridge, K. An Introduction to Qualitative Research. The NIHR Research Design Service for Yorkshire & the Humber. 2009. Available online: http://dl.icdst.org/pdfs/files3/315d0c3a18c9426593c9f5019506a335.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- Van Vliet, J.A.; Schut, A.G.T.; Reidsma, P.; Descheemaeker, K.; Slingerland, M.; Van de Ven, G.W.J.; Giller, K.E. De-mystifying family farming: Features, diversity and trends across the globe. Glob. Food Sec. 2015, 5, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, G.; Durand-lasserve, A. Holding On: Security of Tenure—Types, Policies, Practices and Challenges. Research Paper Prepared for the Special Rapporteur on Adequate Housing as a Component of the Right to an Adequate Standard of Living. 2012, pp. 19–20. Available online: https://landportal.org/library/resources/holding-security-tenure-types-policies-practices-and-challenges (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- Payne, G. Land tenure and property rights: An introduction. Habitat Int. 2004, 28, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christine, M.; Simbizi, D.; Zevenbergen, J.; Bennett, R. Pro-Poor Land Administration and Land Tenure Security Provision. A Focus on Rwanda. GeoTechRwanda 2015, 2014, S1–S10. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, I.; Enemark Jude Wallace, S.; Rajabifard, A. Land Administration for Sustainable Development; ESRI Press Academic: Redlands, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ameyaw, P.D.; Dachaga, W.; Chigbu, U.E.; De Vries, W.T.; Abedi, L. Responsible Land Management: The Basis for Evaluating Customary Land Management in Dormaa Ahenkro, in Ghana. In Proceedings of the World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty, Washington, DC, USA, 19–23 March 2018; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chigbu, U.; Paradza, G.; Dachaga, W. Differentiations in Women’s Land Tenure Experiences: Implications for Women’s Land Access and Tenure Security in Sub-Saharan Africa. Land 2019, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Quamrul, A.; Oded, G. Malthusian Population Dynamics: Theory and Evidence. Work. Pap. 2008, 1–45. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/bro/econwp/2008-6.html (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- Republic of Ghana. Ghana Living Standards Survey Round 5 (GLSS 5); Ghana Statistical Service: Accra, Ghana, 2012.

- Republic of Ghana. Ghana Living Standards Survey Round 6 (GLSS 6); Ghana Statistical Service: Accra, Ghana, 2014.

- Cotula, L.; Neves, B. Changes in ‘Customary’ Land Tenure Systems in Africa; IIED: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 9781843696575. [Google Scholar]

- Dembitzer, B. Lorenzo Cotula: The great African land grab? Agricultural investment and the global food system: African arguments. Food Secur. 2014, 6, 437–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanzo, J. From big to small: The significance of smallholder farms in the global food system. Lancet Planet. Heal. 2017, 1, e15–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullan, K.; Grosjean, P.; Kontoleon, A. Land tenure arrangements and rural-urban migration in China. World Dev. 2011, 39, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arko-adjei, A.; De Jong, J.; Zevenbergen, J.; Tuladhar, A. Customary Land Tenure Dynamics at Peri-urban Ghana: Implications for Land Administration System Modeling. In Proceedings of the FIG Working Week 2009, Eilat, Israel, 3–8 May 2009; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Riesgo, L.; Louhichi, K.; Gomez y Paloma, S.; Hazell, P.; Ricker-Gilbert, J.; Wiggins, S.; Sahn, D.E.; Mishra, A.K. Food and Nutrition Security and Role of Smallholder Farms: Challenges and Opportunities; Publications Office of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2016; ISBN 9789279580161. [Google Scholar]

- International Fund for Agricultural Development. Land Tenure Security; International Fund for Agricultural Development: Rome, Italy, 2015.

- Duncan, B.A.; Brants, C. Access to and Control Over Land from a Gender Perspective; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2004.

- Savenije, H.; Baltissen, G.; Van Ruijven, M.; Verkuijl, H.; Hazelzet, M.; Van Dijk, K. Improving the Positive Impacts of Investments on Smallholder Livelihoods and the Landscapes They Live in Improving the Positive Impacts of Investments on Smallholder Livelihoods and the Landscapes They Live in 2 Disclaimer; FMO: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Boudreaux, B.K.; Sacks, D. Land Tenure Security and Agricultural Productivity; Mercatus Center at George Mason University: Arlington, VA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kyeyune, V.; Turner, S. Yielding to high yields? Critiquing food security definitions and policy implications for ethnic minority livelihoods in upland Vietnam. Geoforum 2016, 71, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrmann, B. Understanding, Preventing and Solving Land Conflicts; GTZ: Eschborn, Germany, 2017; pp. 1–156. Available online: https://www.escr-net.org/sites/default/files/landconflictsguide-web-20170413.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- Wehrmann, B. GTZ_Land_Conflicts Manual-Book; GTZ: Eschborn, Germany, 2008; ISBN 9783000239403. [Google Scholar]

- Gyamera, E. Land Acquisition in Ghana; Dealing with the Challenges and the Way Forward. J. Agric. Econ. 2018, 6, 664–672. [Google Scholar]

- UN Habitat. Toolkit and Guidance for Preventing and Managing: Land and Conflict; UN Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2012.

| Landowner | Male Focus Groups | Number of Participants | Female Focus Groups | Number of Participants | Group Total | Participants Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elderly | 3 | 31 | 3 | 34 | 6 | 65 |

| Disabled | 3 | 29 | 3 | 26 | 6 | 55 |

| “youth” | 3 | 36 | 3 | 35 | 6 | 71 |

| Total | 9 | 96 | 9 | 95 | 18 | 191 |

| Settler | Male Focus Groups | Number of Participants | Female Focus Groups | Number of Participants | Group Total | Participants Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elderly | 3 | 34 | 3 | 35 | 6 | 69 |

| Disabled | 3 | 27 | 3 | 29 | 6 | 56 |

| Middle age | 3 | 36 | 3 | 36 | 6 | 72 |

| Total | 9 | 97 | 9 | 100 | 18 | 197 |

| Concepts Guiding This Research | Analytical Dimensions, Categories and Understanding |

|---|---|

| Customary land rights Land rights inequalities Food security Smallholder farming | Rights derived from local practices through successive generations. The practices in which some have more rights that are stronger while others have fewer and weaker rights. Food security focuses on availability and accessibility constraints that are likely to influence nutrition and stability. Smallholder farming refers to subsistence farming but with the opportunity to sell excess produce. |

| Land rights | Exclusive entitlements derived from accessing and holding land in either customary or more formal settings |

| The relation between formal and informal rights (institutions) | It is a top-down relationship, in which the formal statutory institutions led by the Lands Commission (LC) supervises the customary institutions through documentation, concurrence issuance, verification of claims etc. Informal customary norms and practices may be regarded by the state as primarily important in land matters. They are however, still subject to legal processes administered through the courts. |

| The dynamic interplay among various institutions. Customary, statutory/legal/formal & mixed feature institutions | CLSs were formed as an improvement of the customary system as a lands office operated by landowners with minimal external support. The LC is the state agency that oversees all land matters in Ghana. Private land organisations—Meridia and others carry out land documentation on a small-scale for households, families or communities in Ghana. Such documents are subject to the LC’s approval. |

| The dynamic interplay between actors and institutions | The actors/stakeholders include landowners and settlers, men and women, able-bodied and disabled, and elderly and middle-aged. such actors work through the formal and customary institutions in all matters relating to land—allocations, rights and disputes resolution etc. However, the legal authority of the courts and statutory bodies such as the LC are final in resolving disagreements. |

| S/n | Land Right/Tenure Arrangement | Settler Females | Landowner Females | Settler Males | Landowner Males |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ownership | - | - | - | * |

| 2 | Occupy/use/enjoy | * | * | * | * |

| 3 | Inheritance by heirs | - | - | * | * |

| 4 | Transfer to others | - | - | *- | * |

| 5 | Sale | - | - | - | * |

| 6 | Develop/improve | - | - | * | * |

| 7 | Cultivate/produce | * | * | * | * |

| 8 | Access credit | - | - | - | *- |

| 9 | Enforcement | *- | *- | * | * |

| 10 | Pecuniary/monetary | * | * | * | * |

| 11 | Sharecropping | - | - | - | *- |

| 12 | Rental | - | - | - | *- |

| 13 | Purchase | *- | *- | * | - |

| 14 | Give as gift | - | - | - | * |

| 15 | Common property | *- | *- | *- | *- |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nara, B.B.; Lengoiboni, M.; Zevenbergen, J. Implications of Customary Land Rights Inequalities for Food Security: A Study of Smallholder Farmers in Northwest Ghana. Land 2020, 9, 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9060178

Nara BB, Lengoiboni M, Zevenbergen J. Implications of Customary Land Rights Inequalities for Food Security: A Study of Smallholder Farmers in Northwest Ghana. Land. 2020; 9(6):178. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9060178

Chicago/Turabian StyleNara, Baslyd B., Monica Lengoiboni, and Jaap Zevenbergen. 2020. "Implications of Customary Land Rights Inequalities for Food Security: A Study of Smallholder Farmers in Northwest Ghana" Land 9, no. 6: 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9060178

APA StyleNara, B. B., Lengoiboni, M., & Zevenbergen, J. (2020). Implications of Customary Land Rights Inequalities for Food Security: A Study of Smallholder Farmers in Northwest Ghana. Land, 9(6), 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9060178