Smart Villages: Where Can They Happen?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection

- -

- Thematic (choropleth) maps to show the spatial differentiation of the phenomena;

- -

- Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient to identify the interdependence of the ordinal data;

- -

- Time-series analysis to observe and interpret trends;

- -

- Contingency tables to summarize the interrelatedness between variables.

2.3. Content Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Rural Decline: Where is the Problem?

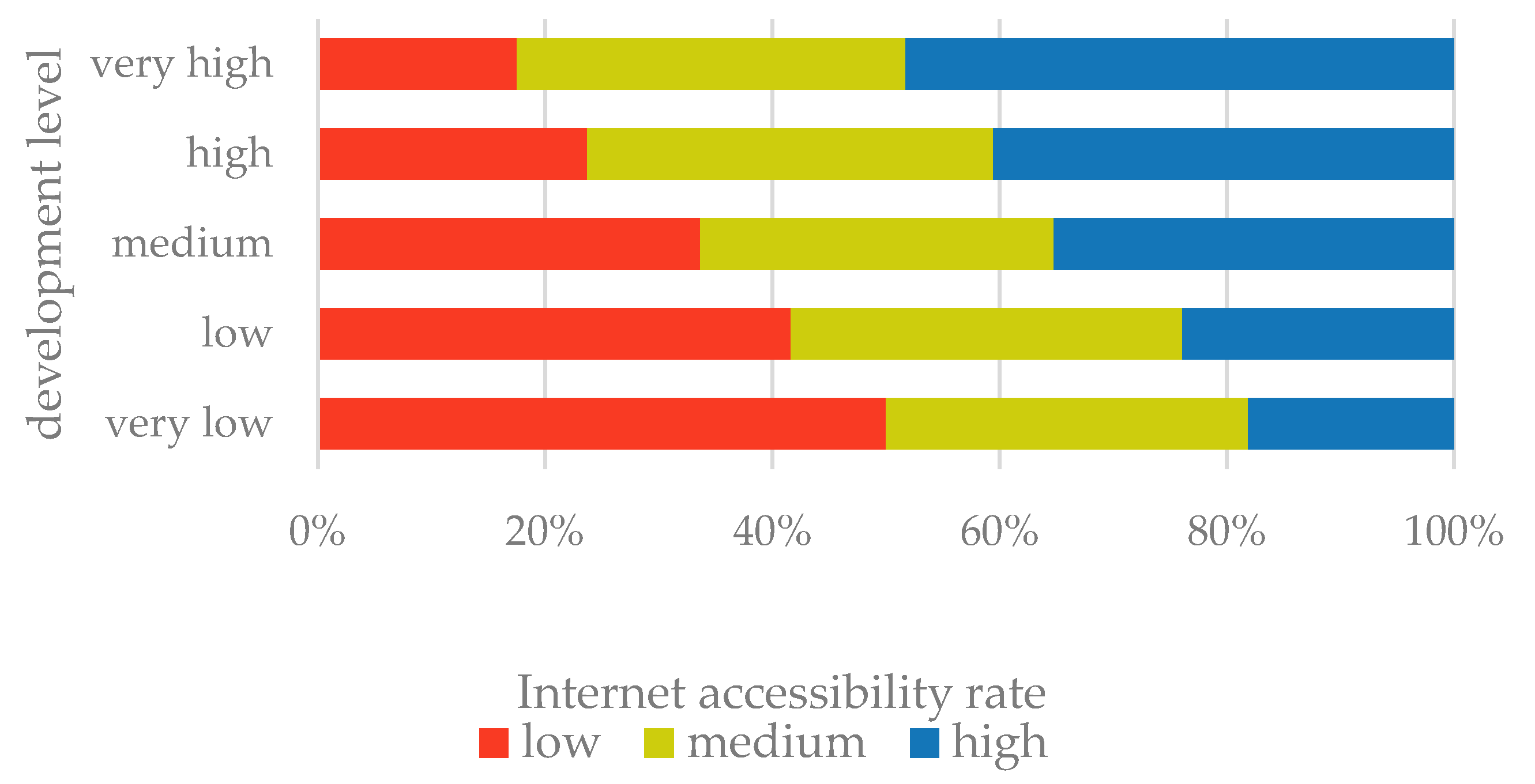

3.2. Development of Information and Communication Technologies in Rural Areas

3.3. Smart Village, Meaning What?

- Build on experience, on the basis of existing forms of collaboration, often long-term and successful, for example related to rural revival or the LEADER approach. The concept should not be allowed to become bureaucratised.

- Start from one village, but build partnership. Smart-village projects have to respond to the needs of local communities, even if they are in small localities. Advisory support in finding funds should be obtained from units specialising in consulting.

- Account for the digital backwardness of rural areas. Although smart villages, unlike smart cities, are not based solely on new technologies, rural residents’ basic access to a (fast and stable) internet network is crucial for local development. Appropriate competences are also important.

- Appreciate people’s activity. The smart-village approach should not be planned without the involvement of local leaders, local government, NGOs and other stakeholders. Existing resources should be utilised, such as active village heads and other local leaders.

- Reward active attitudes. To promote the smart-village concept, it is worth showing rural communities the potential benefits of its implementation, for example with the help of identified, existing examples of smart solutions.

- Make sure the smart-village concept helps small farms. Agriculture is a large area for developing the smart-village concept, as it uses advanced new technologies more and more often. Together with stimulating cooperation among farmers, this creates chances for the development of this segment of the economy, also in places where farming is fragmented and seemingly in decline.

- Involve the consulting sector in supporting smart ideas of local communities. New technologies should be used to develop consulting services, which should ultimately become innovation brokers.

4. Discussion

| Smart Solution Group | Public Services: | Public Management: | Enterprise: |

|---|---|---|---|

| Areas of intervention | power supply (e.g., RES) | e-administration | precision agriculture |

| safety and security (e.g., visual monitoring) | waste management (e.g., container fill-level sensors) | online trade (e.g., in local products) | |

| distance learning | town-and-country planning (e.g., digitisation) | rural tourism (based on smart solutions) | |

| transport (e.g., telebuses) | environmental monitoring (e.g., air quality sensors) | sharing (e.g., of specialist equipment) | |

| e-care | |||

| e-health |

- At the national and regional level, where projects in basic infrastructure (e.g., broadband), development of e-services for different economic sectors (e.g., tourism, agriculture, public health) will be financed. In addition, the environmental component of such projects will be mandatory—thus, national authorities also see an analogy between smart villages and sustainable development.

- At the level of local communities, ideas and strategies of individual villages, their clusters or local action groups (LAGs) are to be supported. The scope of support will depend on the bottom-up smart-village concept” proposed (especially highlighted in Poland).

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bryden, J.M.; Dawe, S.P. Development Strategies for Remote Rural Regions: What Do We Know So Far? 1998. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/17486574/Development_strategies_for_remote_rural_regions_what_do_we_know_so_far (accessed on 3 May 2020).

- Chapman, R.; Slaymaker, T. ICTs and Rural Development: Review of the Literature, Current Interventions and Opportunities for Action; ODI: London, UK, 2002; Working Paper 192. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez, R. Appreciating the contribution of broadband ICT with rural and remote communities: Stepping stones toward an alternative paradigm. Inform. Soc. 2007, 23, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.K.; Thorat, S.B.; Kalyankar, N.V. Reaching the unreached. A role of ICT in sustainable rural development. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Secur. 2010, 7, 220–224. [Google Scholar]

- Salemink, K.; Strijker, D.; Bosworth, G. Rural development in the digital age: A systematic literature review on unequal ICT availability, adoption, and use in rural areas. J. Rur Stud. 2017, 54, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, J. Information Technology and Development: A New Paradigm for Delivering the Internet to Rural Areas in Developing Countries; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, M. The digital vicious cycle: Links between social disadvantage and digital exclusion in rural areas. Telecommun. Policy 2007, 31, 374–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janc, K.; Czapiewski, K.Ł. The internet as a development factor of rural areas and agriculture—Theory vs. Practice. Studia Reg. 2013, 36, 89–105. [Google Scholar]

- Naldi, L.; Nilsson, P.; Westlund, H.; Wixe, S. What is smart rural development? J. Rural Stud. 2015, 40, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ENRD. Smart Villages: Revitalising Rural Services. EU Rural Rev. 2018, 26. Available online: https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/sites/enrd/files/enrd_publications/publi-enrd-rr-26-2018-en.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2020).

- ENRD. Smart Villages: Revitalising Rural Services. 2018. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ckB71hb0kx0 (accessed on 3 May 2020).

- ENRD. How to Support Smart Villages Strategies Which Effectively Empower Rural Communities? Orientations for Policy-Makers and Implementers. 2019. Available online: https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/sites/enrd/files/enrd_publications/smart-villages_orientations_sv-strategies.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2020).

- EC. EU Action for Smart Villages. 2017. Available online: https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/news-events/news/eu-action-smart-villages_en (accessed on 13 February 2020).

- van Gevelt, T.; Holmes, J. A Vision for Smart Villages. 2015. Available online: https://e4sv.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/05-Brief.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2020).

- Cork 2.0 Declaration. 2016. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/sites/agriculture/files/events/2016/rural-development/cork-declaration-2-0_en.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2020).

- Rural People’s Declaration of Candás Asturias. 2019. Available online: https://www.arc2020.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/declaration.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2020).

- OECD. Principles on Urban Policy and on Rural Policy. 2019. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/regional/ministerial/documents/urban-rural-Principles.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2020).

- Davies, N. Volume II: 1795 to the Present. In God’s Playground. A History of Poland; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

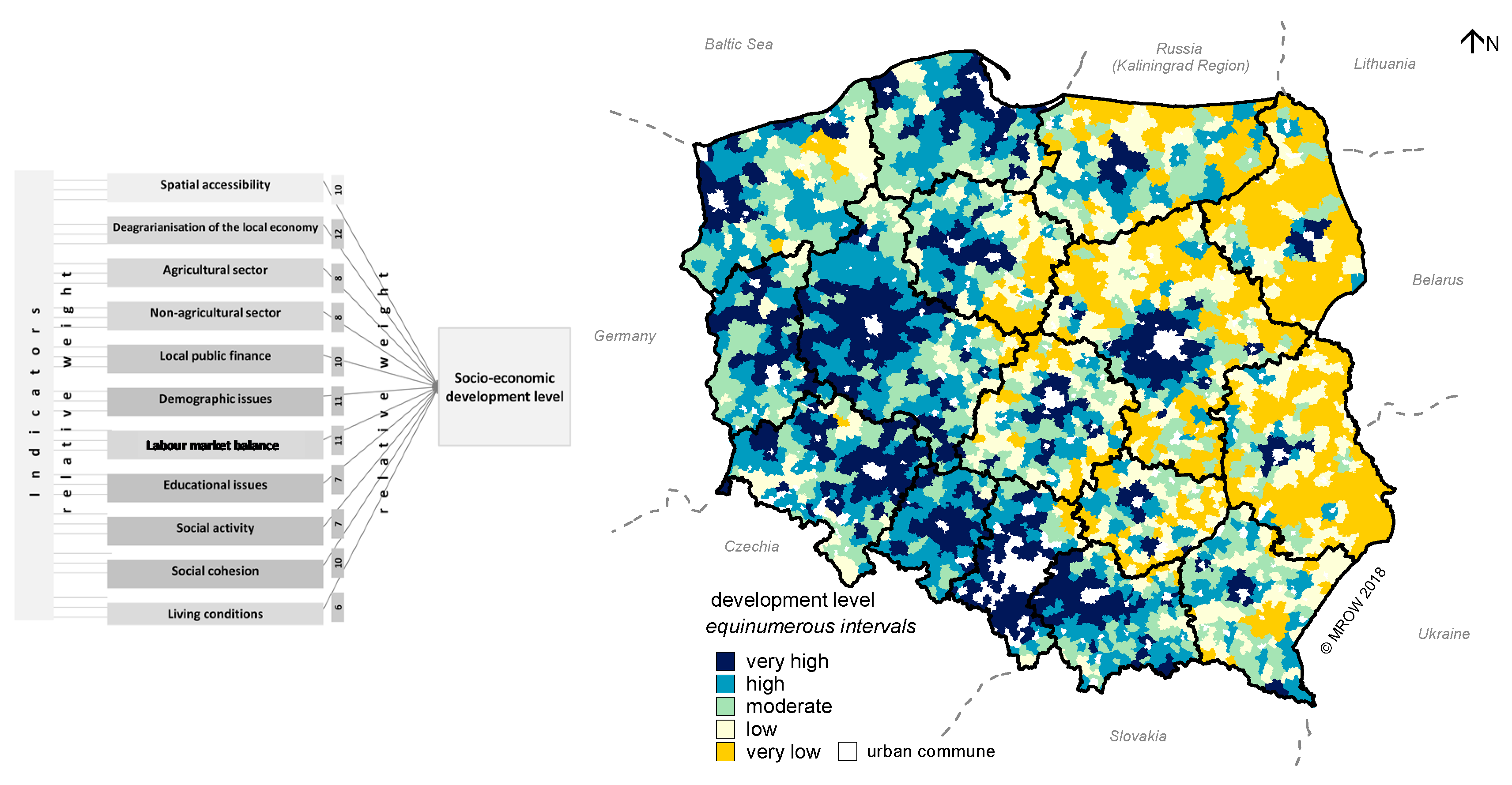

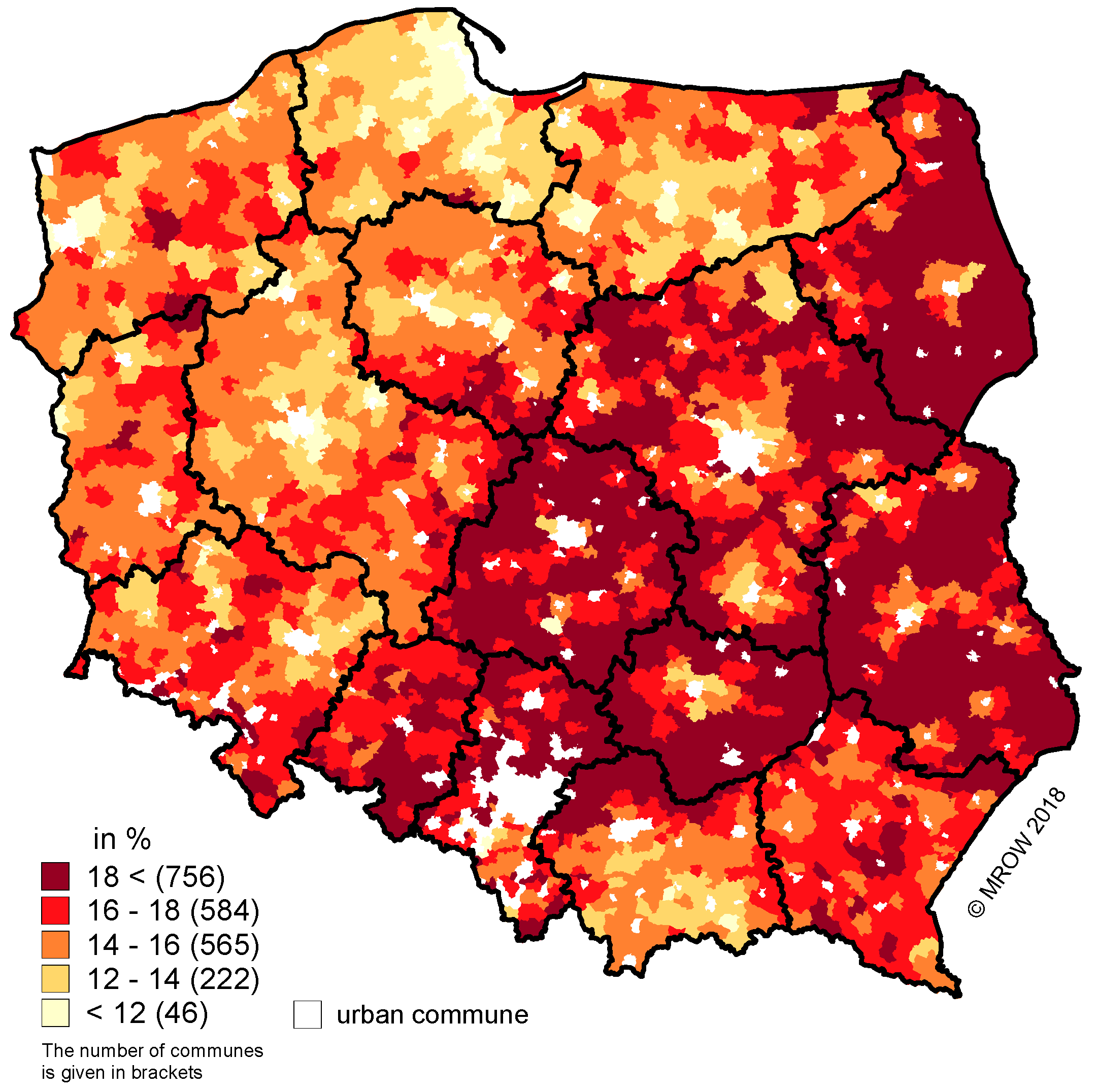

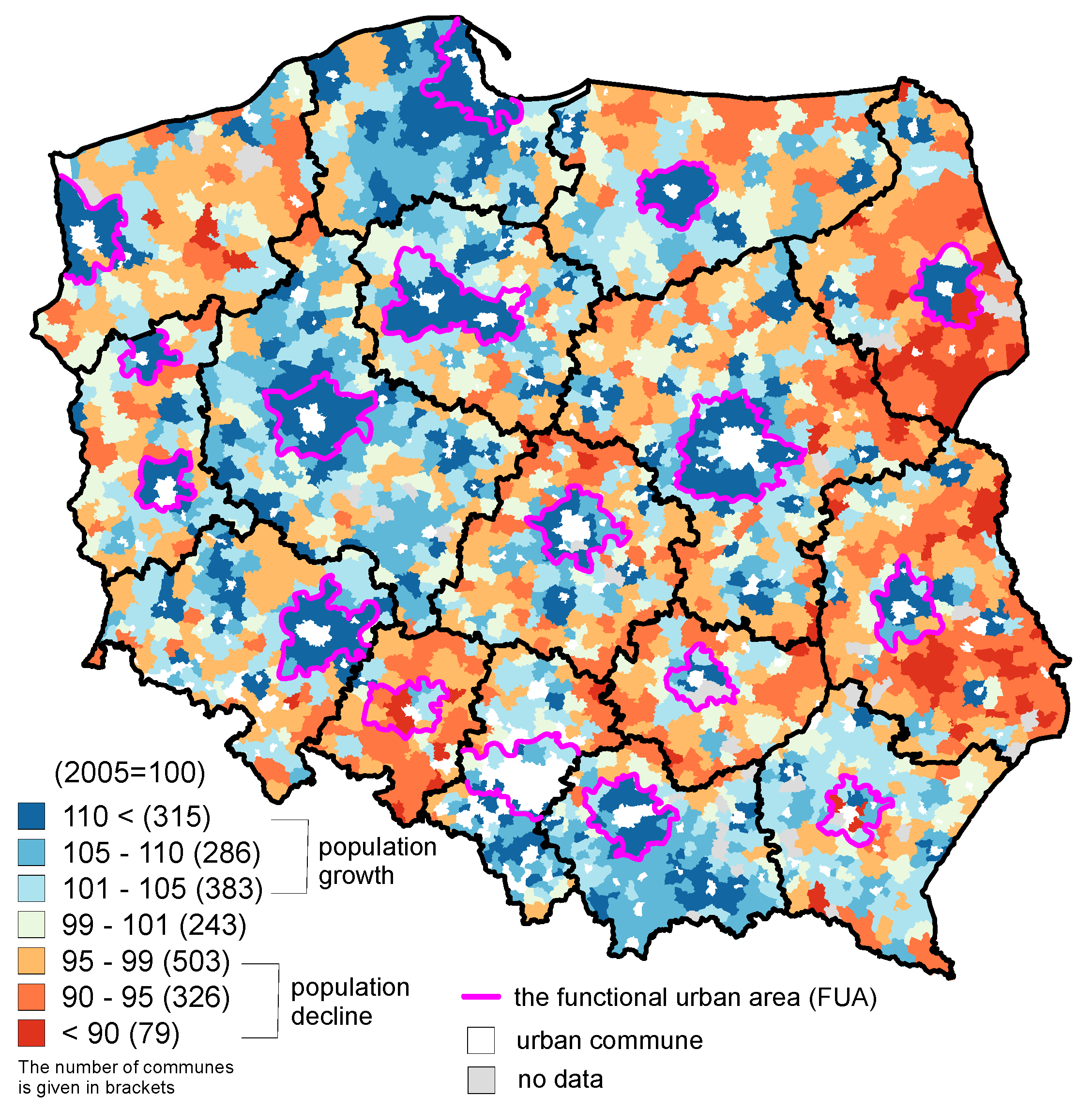

- Rosner, A.; Stanny, M. Socio-Economic Development of Rural Areas in Poland; EFRWP, IRWiR PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

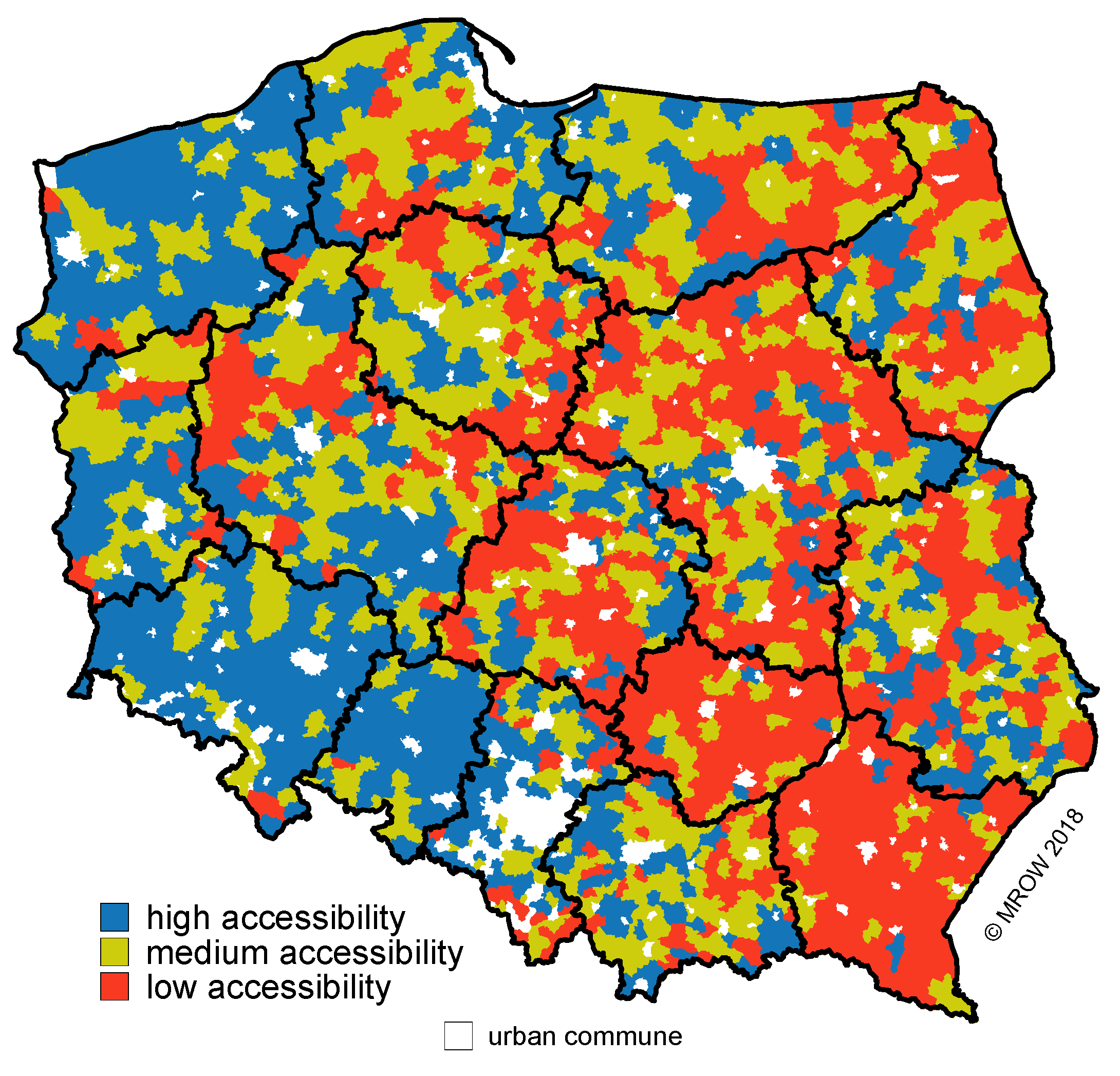

- Stanny, M.; Rosner, A.; Komorowski, Ł. Monitoring Rozwoju Obszarów Wiejskich. Etap III. Struktury Społeczno-Gospodarcze, Ich Przestrzenne Zróżnicowanie i Dynamika (Rural Development Monitoring. Stage III. Socioeconomic Structures, Their Spatial Diversity and Dynamics); EFRWP, IRWiR PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GUS. Rural Areas in Poland—National Agricultural Census 2010. 2013. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/agriculture-forestry/national-agricultural-census-2010/rural-areas-in-poland-national-agricultural-census-2010,1,1.html (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- Stanny, M.; Rosner, A.; Komorowski, Ł. The Relationship between the Level of development and the socio economic structure of Rural Areas. Poland: At the junction of Eastern and Western Europe. IRWiR PAN. under review.

- ESPON. Shrinking rural regions in Europe. Towards Smart and Innovative Approaches to Regional Development Challenges in Depopulating Rural Regions. 2017. Available online: https://www.espon.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/ESPON%20Policy%20Brief%20on%20Shrinking%20Rural%20Regions.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2020).

- Stasiak, A. Problems of Depopulation of Rural Areas in Poland after 1950. In The Processes of Depopulation of Rural Areas in Central and Eastern Europe; Stasiak, A., Mirowski, W., Eds.; IGiPZ PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 1990; Conference Papers 8; pp. 13–37. [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel, I.; Rosner, A.; Stanny, M. Kształtowanie się populacji ludności wiejskiej (Rural population development). In Ciągłość i zmiana. Sto lat Rozwoju Polskiej Wsi (Continuity and Change: A Hundred Years of the Development of Polish Rural Areas); Halamska, M., Stanny, M., Wilkin, J., Eds.; IRWiR PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 77–117. [Google Scholar]

- Flaga, M.; Wesołowska, M. Demographic and social degradation in the Lubelskie Voivodeship as a peripheral area of East Poland. Bull. Geogr. Socio-Econ. Ser. 2018, 41, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halamska, M. Wspierać czy zalesiać? Dylematy rozwoju wiejskich obszarów problemowych (Supporting or Afforesting? Dilemmas in the Development of Rural Problem Areas in Poland). Wieś I Rol. 2018, 180, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Westlund, H.; Liu, Y. Why some rural areas decline while some others not: An overview of rural evolution in the world. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 68, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OF. Błędne Koło Niedorozwoju (The Vicious Circle of Underdevelopment). 2019. Available online: https://www.obserwatorfinansowy.pl/tematyka/makroekonomia/bledne-kolo-niedorozwoju (accessed on 4 March 2020).

- Czarnecki, A. Urbanizacja Kraju I Jej Etapy (Urbanization of the Country and Its Stages). In Ciągłość i zmiana. Sto Lat Rozwoju Polskiej Wsi (Continuity and Change: A Hundred Years of the Development of Polish Rural Areas); Halamska, M., Stanny, M., Wilkin, J., Eds.; IRWiR PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 51–76. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Glossary: Functional Urban Area. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Glossary:Functional_urban_area (accessed on 3 May 2020).

- Rosner, A. Zmiany Rozkładu Przestrzennego Zaludnienia Obszarów Wiejskich. Wiejskie Obszary Zmniejszające Zaludnienie I Koncentrujące Ludność Wiejską (Changes in the Spatial Distribution of Rural Population. Rural Areas Reducing and Concentrating Rural Population); IRWiR PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Grabowska-Lusińska, I. Migrations from Poland after 1 May 2004 with Special Focus on British Isles. Space Popul. Soc. 2008, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śleszyński, P. Delimitacja miejskich obszarów funkcjonalnych stolic województw (Delimitation of the Functional Urban. Areas around Poland’s voivodship capital cities). Przegląd Geograficzny 2013, 85, 173–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravenstein, E.G. The Birthplaces of the People and the Laws of Migration; Trübner & Co., Ludgate Hill, E.C.: London, UK, 1876. [Google Scholar]

- Stanny, M. Dynamika zmian demograficznych ludności wiejskiej i jej zasobów pracy (Demography of Rural Areas in Poland). Polityka Społeczna 2012, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Rosner, A. Współczesne procesy zmian zaludnienia obszarów wiejskich w Polsce (Contemporary Processes of Population Changes of Rural Areas in Poland). In Obszary Wiejskie. Wiejska Przestrzeń I Ludność, Aktywność Społeczna I Przedsiębiorczość (Rural Areas—Countryside Expanse and Population, Social Activity and Enterpreneurship); Heffner, K., Klemens, B., Eds.; KPZK PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2016; Volume 167, pp. 232–249. [Google Scholar]

- Paniagua, A. Smart Villages in Depopulated Areas. In Smart Village Technology. Concepts and Developments; Patnaik, S., Sen, S., Mahmoud, M.S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 17, pp. 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, R.; Hunt, P. Telecentre Evaluation: A Global Perspective. Report of an International Meeting on Telecentre Evaluation; Gómez, R., Hunt, P., Eds.; IDRC: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kaleta, A. Telechata jako instrument zrównoważonego rozwoju obszarów wiejskich (Telecottage as a tool of the rural areas sustainable development). Annales Universitatis Mariae Curiae-Skłodowska Sectio I Philosophia-Sociologia 2011, 36, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundin, R. Communications Technology. In Think Tank on Research into Rural Education, Proceedings of the Conference Held by the RERDC, Townsville, Australia, 10–14 June 1990; McShane, W., Ed.; James Cook University: Townsville, Australia, 1990; pp. 90–99. [Google Scholar]

- Komorowski, Ł.; Stanny, M. (R)ewolucja wyposażenia wsi w wodę, prąd i telefon ((R)evolution in bringing water, electricity and telephones to rural areas). In Ciągłość i Zmiana. Sto Lat Rozwoju Polskiej Wsi (Continuity and Change. Hundred Years of the Development of Polish Rural Areas); Halamska, M., Stanny, M., Wilkin, J., Eds.; IRWiR PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2019; Volume 2, pp. 761–801. [Google Scholar]

- GUS. Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Poland. 2017. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/statistical-yearbooks/statistical-yearbooks/statistical-yearbook-of-the-republic-of-poland-2017,2,17.html (accessed on 10 February 2020).

- GUS. Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Poland. 2019. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/statistical-yearbooks/statistical-yearbooks/statistical-yearbook-of-the-republic-of-poland-2019,2,21.html (accessed on 10 February 2020).

- POPC. Lista Projektów (List of Projects). Available online: https://www.polskacyfrowa.gov.pl/strony/o-programie/projekty/lista-beneficjentow/ (accessed on 3 May 2020).

- MFiPR. Wpływ Polityki Spójności na Rozwój Obszarów Wiejskich (The Impact of Cohesion Policy on Rural Development). 2019. Available online: https://www.ewaluacja.gov.pl/strony/badania-i-analizy/wyniki-badan-ewaluacyjnych/badania-ewaluacyjne/wplyw-polityki-spojnosci-na-rozwoj-obszarow-wiejskich/ (accessed on 15 April 2020).

- KSOW. Rekomendacje KSOW Wobec Smart Villages (KSOW Recommendations for Smart Villages). 2019. Available online: http://ksow.pl/news/entry/15022-rekomendacje-ksow-wobec-smart-villages.html (accessed on 16 February 2020).

- Komorowski, Ł. Laboratorium Smart Villages: Wizyta w Fińskich Smart Wsiach (Smart Village Laboratory: A Visit to Finnish Smart Villages). 2019. Available online: http://ksow.pl/news/entry/15075-laboratorium-smart-villages-wizyta-w-finskich.html (accessed on 16 February 2020).

- Guzal-Dec, D. Inteligentny Rozwój Wsi—Koncepcja Smart Villages: Założenia, Możliwości I Ograniczenia Implementacyjne (Intelligent Development of the Countryside—the Concept of Smart Villages: Assumptions, Possibilities and Implementation Limitations). Econ. Reg. Stud. 2018, 3, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-delHoyo, R.; Mora, H. Toward a New Sustainable Development Model for Smart Villages. In Smart Villages in the EU and Beyond; Visvizi, A., Lytras, M.D., Mudri, G., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2019; pp. 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slee, B. Delivering on the concept of smart villages—in search of an enabling theory. Eur. Countrys. 2019, 11, 634–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolski, O.; Wójcik, M. Smart Villages Revisited: Conceptual Background and New Challenges at the Local Level. In Smart Villages in the EU and Beyond; Visvizi, A., Lytras, M.D., Mudri, G., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2019; pp. 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A. IOT, Smart Technologies, Smart Policing: The Impact for Rural Communities. In Smart Village Technology. Concepts and Developments; Patnaik, S., Sen, S., Mahmoud, M.S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 17, pp. 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwolińska-Ligaj, M.; Guzal-Dec, D.; Adamowicz, M. Koncepcja inteligentnego rozwoju lokalnych jednostek terytorialnych na obszarach wiejskich regionu peryferyjnego na przykładzie województwa lubelskiego (The Concept of Smart Development of Local Territorial Units in Peripheral Rural Areas: The Case of Lublin Voivodeship). Wieś I Rol. 2018, 179, 247–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishar, A.; Šťastná, M. Smart village and sustainability. Southern Moravia case study. Eur. Countrys. 2019, 11, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonenberg, W.; Qi, L.; Zhou, M.; Wei, X. Smart Village as a Model of Sustainable Development. Case Study of Wielkopolska Region in Poland. In Advances in Human Factors in Architecture, Sustainable Urban Planning and Infrastructure; Charytonowicz, J., Falcão, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidyba, M.; Makowski, Ł. Smart City. Innowacyjne Rozwiązania w Administracji Publicznej a Zarządzanie Inteligentnym Miastem (Smart City: Innovative Solutions in Public Administration vs. Smart city Management); Wydawnictwo WSB: Poznań, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fajrillah, F.; Mohamad, Z.; Novarika, W. Smart city vs smart village. J. Mantik Penusa 2018, 22, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Visvizi, A.; Lytras, M.D. Rescaling and refocusing smart cities research: From mega cities to smart villages. J. Sci. Tech. Pol. Manag. 2018, 9, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavratnik, V.; Kos, A.; Duh, E.S. Smart villages: Comprehensive review of initiatives and practices. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, J.A.; Adawiyah, R. Smart city (SC)—smart village (SV) and the ‘Rurban’ concept from a malaysia-indonesia perspective. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2019, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.; Cha, J. A Trend on smart village and implementation of smart village platform. Inter. J. Adv. Smart Converg. 2019, 8, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visvizi, A.; Lytras, M.D. It’s not a fad: Smart cities and smart villages research in European and global contexts. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, L.; Williams, F. Healthy ageing in smart villages? Observations from the field. Eur. Countrys. 2019, 11, 616–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Rural 3.0. A Framework for Rural Development. 2018. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/regional-policy/Rural-3.0-Policy-Note.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- MFiPR. Krajowa Strategia Rozwoju Regionalnego 2030. Rozwój Społecznie Wrażliwy I Terytorialnie Zrównoważony (National Regional Development Strategy 2030: Socially Sensitive and Territorially Sustainable Development). 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/fundusze-regiony/krajowa-strategia-rozwoju-regionalnego (accessed on 14 February 2020).

- Bled Declaration. 2018. Available online: http://pametne-vasi.info/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Bled-declaration-for-a-Smarter-Future-of-the-Rural-Areas-in-EU.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2020).

- ENRD Thematic Group “Smart Villages”. Available online: https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/enrd-thematic-work/smart-and-competitive-rural-areas/smart-villages_en (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Jedlińska, R.; Rogowska, B. Rozwój e-administracji w polsce (The development of e-administration in Poland). Ekon. Probl. Usług 2016, 123, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Śledziewska, K.; Zięba, D. E-Administracja w Polsce na tle Unii Europejskiej. Jak z Niej (nie) Korzystamy (E-Administration in Poland Compared to the European Union: How We Are (Not) Using It); Digital Economy Lab UW: Warsaw, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Maaseutu. Smart Villages in Finland, Plans for the Future. 2019. Available online: https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/sites/enrd/files/tg9_smart-villages_future-interventions_selkainaho.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2020).

- MARD. The Existing Rural Development Measures and Idea for Future Framework for Supporting Smart Villages in Poland. 2020. Available online: https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/sites/enrd/files/5_tg11_smart-villages_sv-interventions_gierulska_0.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2020).

- Haider, M.F.; Siddique, A.R.; Alam, S. An approach to implement frees space optical (FSO) technology for smart village energy autonomous systems. Far East. J. Electron. Commun. 2018, 18, 439–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GUS. Społeczeństwo Informacyjne w Polsce w 2019 r. (The Information Society in Poland in 2019). 2019. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/nauka-i-technika-spoleczenstwo-informacyjne/spoleczenstwo-informacyjne/spoleczenstwo-informacyjne-w-polsce-w-2019-roku,2,9.html (accessed on 14 February 2020).

- Batorski, D. Technologies and Media in Households and Lives of Poles. In Social Diagnosis 2015, The Objective and Subjective Quality of Life In Poland; Czapiński, J., Panek, T., Eds.; Contemporary Economics: Warsaw, Poland, 2015; Volume 9/4, pp. 367–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalega, T. Korzystanie z Internetu i Wirtualizacja Konsumpcji Wśród Polskich Seniorów: Wyniki Badań Bezpośrednich (The use of the Internet and the Virtualisation of Consumption among Polish Seniors: The Results of Primary Research). In Organizacja Społeczna w Strukturach Sieci: Doświadczenia i Perspektywy Rozwoju w Europie Środkowej i Wschodniej (Social Organisation in Network Structures: Experiences and Development Prospects in Central and Eastern Europe); Betlej, A., Partycki, S., Parzyszek, M.J., Eds.; Wydawnictwo KUL: Lublin, Poland, 2016; pp. 138–153. [Google Scholar]

- Kolkowska, E.; Soja, E.; Soja, P. Implementation of ICT for Active and Healthy Ageing: Comparing Value-Based Objectives Between Polish and Swedish Seniors. In Information Systems: Research, Development, Applications, Education; Wrycza, S., Maślankowski, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 333, pp. 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyn, M. Digitalization and Its Impact on Life in Rural Areas: Exploring the Two Sides of the Atlantic: USA and Germany. In Smart Village Technology. Concepts and Developments; Patnaik, S., Sen, S., Mahmoud, M.S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 17, pp. 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursula von der Leyen A Union that Strives for More. My Agenda for Europe. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/political-guidelines-next-commission_en.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2020).

| 1 | Socioeconomic development is understood as “the process of transforming rural areas into an inhabitant-friendly environment, i.e., one which allows them to fulfil their needs and aspirations, particularly with regard to labour conditions and obtaining satisfactory income; access to public services and broadly defined cultural goods; a sense of participation in the life of the local community; a sense of agency in the ongoing transformation; etc.” [19] (p. 13). According to the MROW study, “to obtain one evaluation that would characterise an object from many standard features, all standardised variables for each object should be summed. The evaluation of a variable that characterises an i-th object is called a ‘synthetic variable’. A synthetic variable obtained from following Formula (2) assumes values within the range 0–1: where a′ij is the normalised value of the j-th feature in the i-th object (after the destimulant is changed to stimulant), n is number of objects, and mi is the weight factor of an i feature” [22]. |

| 2 | The organiser was the Institute of Rural and Agricultural Development of the Polish Academy of Sciences, call for applications 3/2019 of the Polish Rural Network (KSOW). The project involved a competition for descriptions of smart-village initiatives, which contributed to disseminating and promoting the concept among rural residents, identifying a wide range of social and digital innovations emerging in rural areas, and presenting them in a knowledge bank. |

| 3 | “A functional urban area consists of a city and its commuting zone. Functional urban areas therefore consist of a densely inhabited city and a less densely populated commuting zone whose labour market is highly integrated with the city” [31]. |

| 4 | The internet accessibility rate is measured as the ratio of the number of network terminations enabling internet services to be provided in a given area to the number of housing units in that area. |

| 5 | The questionnaire form was filled in by the commune office. The response rate was 95% (N = 2064). |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Komorowski, Ł.; Stanny, M. Smart Villages: Where Can They Happen? Land 2020, 9, 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9050151

Komorowski Ł, Stanny M. Smart Villages: Where Can They Happen? Land. 2020; 9(5):151. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9050151

Chicago/Turabian StyleKomorowski, Łukasz, and Monika Stanny. 2020. "Smart Villages: Where Can They Happen?" Land 9, no. 5: 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9050151

APA StyleKomorowski, Ł., & Stanny, M. (2020). Smart Villages: Where Can They Happen? Land, 9(5), 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9050151